Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12120

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFICPAPERS

Portuguese and Brazilian national cultures, organizational culture and trust: an analysis of impacts

Culturas Brasileira e Portuguesa, cultura organizacional e confiança: uma análise de impactos

Lúcio Flávio Renault de Moraes1, Anderson de Souza SantAnna2, Daniela Martins Diniz3, Fátima Bayma de Oliveira4

1Faculdade de Pedro Leopoldo, Mestrado Profissional em Administração, Rua Teófilo Calazans de Barros, 100, Pedro Leopoldo, Minas Gerais CEP 30190-080, Brasil.E-mail: luciorenault@gmail.com

2Fundação Dom Cabral, Núcleo de Liderança, Av. Princesa Diana 760, Alphaville, Lagoa dos Ingleses, 34000-000 - Nova Lima, Minas Gerais, Brasil.E-mail: anderson@fdc.org.br

3Universidade Federal de MG, Doutorado em Administração, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627 / sala 4012 - Pampulha - 31270-901 - Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brasil.E-mail:danidiniz09@yahoo.com.br

4Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Educação, Praia de Botafogo, 190, Rio de Janeiro, 22250-900, Brasil. E-mail: fbayma@fgv.br

ABSTRACT

The objective of this paper is to investigate the influence of trace constituents of Brazilian and Portuguese cultures on the establishment of relationships of trust. For this purpose the head office of a Portuguese multinational company and its subsidiary in Brazil were investigated, by means of research of a qualitative nature, utilizing the case study method. Regarding data collection, twelve interviews were carried out with managers drawn from both countries, based on an interview script developed from a wide-ranging review of the literature on the theme, especially that written from the anthropological perspective, as proposed by Schein (1986). The reports of the interviews gave evidence of the relevance of a more effective management of cultural artefacts, in particular greater attention to the sharing of values, in order to foster the building of stronger bonds of trust and to stimulate cultural contexts more in tune with contemporary organizational discourse.

Keywords: Culture, national culture, organizational culture, cultural diversity, trust.

RESUMO

Este artigo tem como objetivo central investigar a influência de traços constituintes das culturas brasileira e portuguesa no estabelecimento de relações de confiança. Para tal foi investigada matriz de multinacional portuguesa e sua subsidiária no Brasil. Norteado por esse propósito realizou-se pesquisa de natureza qualitativa e caráter descritivo-analítico, utilizando-se como método o estudo de caso. Em termos da coleta de dados, foram conduzidas doze entrevistas semiestruturadas e em profundidade com gestores de ambos os países, tendo por base roteiro desenvolvido a partir de ampla revisão de literatura sobre o tema, com destaque para a perspectiva antropológica, conforme proposta por Schein (1992). À luz dos relatos das entrevistas obtidas evidencia-se a relevância de gestão mais efetiva dos artefatos da cultura, em particular maior atenção ao compartilhamento de valores, de modo a se fomentar a construção de laços mais fortes de confiança e estimular contextos culturais mais aderentes aos discursos organizacionais contemporâneos.

Palavras-chave: Cultura, cultura nacional, cultura organizacional, diversidade cultural, confiança.

1. Introduction

A review of scientific production on the manner in which organizational behaviour various culturally reveals a significant number of research works – notably from the 1980s on - that point out differences in values, attitudes and behaviour in a working situation (Hofstede, 1984; Segnini, 1988).

Motta e Caldas (1997) declares that for some time anthropology has devoted itself to cultural variation among human groupings or societies, while recognizing that studies of the forms assumed by such differences in the world of work are recent. According to the author: [...] about 30 years ago it was believed that any administrative, work or organizational situations, could be dealt with through the use of some general rules, applied to all of them, without any consideration of their contexts (Motta & Caldas, 1997, p. 155). At the same time, Giddens (1991) highlights the continual importance of the dimension of trust, in the analysis of the dynamic of such contexts, stressing that to trust involves the attribution of probity (honour) to the other and belief in the correctness of the ruling principles in the environment – requiring the preparation of a conceptual bridge between the attribution of probity and belief, as well as to the act of commitment.

It must be considered therefore that the situations in the world of work pass through the filters of beliefs and attitudes that each one of the players brings to them. The preparation of such a bridge – between trust and culture – depends directly, however, on an understanding of the historical, social, psychological and cultural conditions.

Further, as common values and shared visions favour the development of relations of trust and that standards and values, acting in coordinated fashion, tend to generate strong bonds of this nature (Leana & Burren, 1999), it is the time to analyse the cultural substratum upon which standards and organizational values are supported.

In dealing with the Brazilian national culture for example, it is opportune to remind ourselves that the countries colonized in Latin America, Asia and Africa did not develop because of endogenous processes, nor usually did they adopt their own mechanisms for evaluating the results of the interventions imposed on them. In addition, the awareness of the local populations was not always formed by the inhabitants. Buarque (1990) stresses that Brazilian progress, built up from notions generated in the metropolitan countries –initially European, and subsequently North American – can only be badly adapted to our cultural reality, and maladjusted to the needs of its population.

Motta e Caldas (1997) adds that Brazil never underwent a bourgeois revolution, as a doubly articulated norm characterises the domination of the elites in the country. The first term of this double articulation, in which the archaic coexists with the modern, is unequal internal development. The second refers to the dependence and submission to more important centres, both in the economic as in the mass cultural spheres, as regards the standards of consumption. In this manner, as in other Latin American nations, the Brazilian bourgeoisie bears its contradictions and it is probable that the recurring military coup détats, throughout the course of its history, can be seen as reflections and typical forms of its articulations.

In view of this, it is clear that Brazilian national culture has evident ties with the culture of the colonizer, reflected in the values expressed, in the adopted language and in the behaviour of the dominant class, which remind one of external norms. And even in festivals, religious, collective manifestations, that not rarely attempt to dodge the exacerbated domination of the colonizers, in particular in the origins of its constitution, by the Portuguese.

As has been seen, the analysis of this influence in the workplace has only more recently been explored and this paper intends to offer a contribution to this scientific production. Thus, its proposal consists in presenting the results of research to investigate the relationships between the national cultures – in this case specifically, between the Brazilian and Portuguese cultures – and organizational culture, using the construct of Trust.

To this end, it was sought to investigate the influence of constituent traces of Brazilian and Portuguese cultures in the establishment of relationships of trust, examining the classical and contemporary literature on the theme, and having as specific objectives: 1. The characterization of the main aspects of Portuguese and Brazilian cultures, establishing relations between them; 2. The identification, in the reports of Brazilian and Portuguese managers, drawn from the daily routine of their work, cultural manifestations of the countries in which the units investigated in this study are established: the headquarters of a Portuguese multinational and its subsidiary in Brazil; 3. The discussion of the Trust construct in relation to the constituent traces of Brazilian and Portuguese reality; 4. To distinguish factors that facilitate and inhibit the development of organizational relationships of trust; 5. To compare the data obtained in the organizations Portuguese and Brazilian units which are the subject of this study.

It should be pointed out that the option for adopting the construct of trust as a mediator for the purposes of this proposal arose, notably, from its potential to indicate conditioning factors that underlie cultural behaviour, in its wider sense. For this reason, it is fitting, before the presentation of the methodology adopted, to dedicate a little space to characterizing the traces and relationships between Portuguese and Brazilian culture, starting from an ample review and debate of the scientific production available on the theme, especially in sociology; as well as to discoursing on the articulations, increasingly pronounced, between the national culture and organizational culture constructs, considering the relevance attributed to them in the present day, characterized by the globalization of economies, markets and organizations.

Finally, it is worth stressing its contributions in terms of the widening of the nomological chain in studies on the construct under analysis, considering in particular the implications of national cultures. In practical terms, there is the objective of contributing elements that make improvements possible in the managerial policies and practices of multicultural teams.

2. Theoretical approach

2.1 National and organizational cultures

Reverting to Giddens (1991), it can be stated that the survival of organizations, in particular in the present context of permanent transformations, is increasingly linked to the possibility of these organisms adapting to an environment of continual insecurity. Along this line, recent studies have tried to analyse differences of managerial and leadership styles, on a world scale. Laurent (1981), for example, studied administrators in nine European and Asiatic countries, in addition to the United States, to identify distinct standards of behaviour presented by them faced with 60 daily work situations, drawing conclusions regarding the prevalence of significant differences in style.

Following in the tradition of contemporary anthropology, DIribarne (1989) states that human beings live in a universe of significations, in which they decode the words, expressions, postures and actions of their fellow creatures. This signification is not, however, universal. It is related to a species of private language, to a code, culture being one of these codes, which permits people to attribute meaning to the world in which they live and to their actions. In this way, culture influences the orientations adopted within each social grouping. From such a perspective, this author studied three cultures and three organizations that operate in very diverse national cultures regarding their guiding logic: the logic of honour (France), of fair exchange between equals (United States) and of consensus (Holland), allowing him to corroborate his thesis.

Hofstede (1984), starting from quantitative approaches, carried out surveys in 60 countries, in which he had the opportunity to collect data relative to 160,000 executives and subordinates, all of them from a large north American multinational company, which possessed units in various parts of the world, in the West, and in the East.

According to Motta e Caldas (1997), the most important conclusion of Hofstedes studies refers to the importance attributed to the national culture as a determinant of work-related attitudes and values. This author, whose findings have had significant influence on studies on this theme, identified four basic dimensions that influence behaviour both for executives, as well as professionals and work people: individualism and collectivism, distance from power, the degree to which one avoids uncertainty, and masculinity – femininity.

Carrieri (2002), starting from the review of classical and contemporary approaches to organizational culture, concluded by pointing out that in the present context – marked by the expansion of new organizational configurations, such as virtual companies, organization into networks and/or global – the research suggests that national culture will tend to have increasingly significant impacts on its members, than culture at the strictly organizational level: however strong the organizational culture in modelling the behaviour of its members, the culture of the country will have a marked influence. Notwithstanding this, Motta e Caldas (1997) point out that studies are still few which are directed to the analysis of Brazilian corporate culture and that take into account their roots, formation and evolution, as well as the traces of national cultures that have produced them (Nery-Kierfve & McLean, 2015; SantAnna, 2013; Carrieri, 2002).

2.1.1 The Portuguese and Brazilian cultures

The start of the formation of a sense of nationality, in Brazil, goes back to the end of the 17th century, and start of the 18th, that is, long after the official discovery of territory by the Portuguese, in 1500. According to Moraes (2007), although the question who is a Brazilian? is late, the formation of Brazilian identity started long before: initially, with the fusion of the Indians (the first , the non Brazilians, the first ingredient of the mixture ) with Portuguese and, subsequently, with the arrival of the Africans and others who peopled the country and brought with them their contributions to the formation of Brazilian culture.

Ribeiro (1995) argues that Brazil is in contrast to the native peoples, like those of Mexico and the Andean Altiplano – arising from high civilizations and living the drama of cultural duality with the colonizers culture: of the transplanted peoples – as in the United States of America and Canada – characterized by the reproduction of the European human values and landscapes – and of the new peoples – as in Latin America - being produced.

In talking of the results of interactions between the different metropolitan countries and their colonies, Holanda (1984), while recognizing that the cities built in the Spanish and Portuguese Colonies were instruments of domination, differentiates the forms under which the colonizing processes were pursued. The Spanish crown, unlike the Portuguese, established various cities in its Colonies. The author goes into some detail about how these cities were constructed and contrasts them with the manner in which the few Portuguese cities were established.

In addition, while Portuguese colonization concentrated itself predominantly along the coast, Spanish colonization pushed inland into the interior and the plateaus. This form of colonization had direct impacts on the relations of those recently arrived with the peoples that inhabited the country and with the descendants produced from such interactions. Holanda (1984) discourses further on some other aspects peculiar to this colonization; he mentions, for example, the desire the greater part of the Portuguese population had to achieve nobility and how such a desire can be easily seen in Brazil. He stresses also the relation between this sentiment of nobility and the aversion to physical work – which in no way dignified man – and an organizational laxity very present in the history of Portugal and, also, that of Brazil.

Analogously, Paula (2005) recognizes traces of the Portuguese mentality from the time of the discoveries to the present day in the Brazilian identity. Traces such as the belief in the realization of the impossible, in saviour heroes, in the transubstantiation of acts and facts, in the providential view of history and in the idea of the governor as equivalent to king by the grace of God, capable of distributing such grace and always willing to confuse the public and private spheres; traces which are still present today in the relationships of authority.

One of the first consequences of this cultural shock was the introduction of the social institution that provided ballast for the formation of the Brazilian people: the practice of brother-in-law-ism. In colonial Brazil, this brother-in-law-ism consisted in offering the foreigner an indigenous woman as a wife. As soon as he took her to wife, the recent arrival established, automatically, ties that would make him a relation of all the members of the group. As it was usual for a Portuguese to have many wives, a large number of illegitimate children were generated, lost between two worlds, neither entirely Indian, nor Portuguese. The resulting problematic identity –belonging neither to the forest, nor to the township – resulted in a sentiment of nobodyness (Ribeiro, 1995).

Paula (2005) complements this, stating that the absence of strong references in the law leads this orphan child to the opposite side: to seek refuge in the search for magical solutions with rapid satisfaction of the desires in the place of restraint and collective resignation in the name of the law and moderate pleasure.

The theme of radical abandonment, where there has not yet occurred a reconciliation with the origins, is complemented by identification with superior people, with the objective of reproducing an external identity as a substitute for what is as yet unformed. These elements form a nucleus that constitutes a model for Brazilian entrepreneurial "heroism", marked by a latent destruction and a culture of cordial voracity (Paula, 2005; Holanda, 1984).

The unique configuration of Brazilian culture has, according to these authors, a significant impact on its peoples world view. This difference should be evident, mainly in the case of situations where the peculiar characteristics can constitute threats; although, equally, inexhaustible supplies of advantages and competitive differentiation.

2.2 Organizational culture

In accordance with the Critical Dictionary of Management and Psychodynamics of Work (Vieira, Mendes & Merlo, 2013), the organizational culture theme is well apprehended by Carrieri (2002), in characterizing it as ample, complex and profound. Ample because one can see it as an empirical object, a variable, as well as a metaphor of the organization itself and of the social reality into which it is inserted. Complex, because one can understand organizational culture as unique and consensual, or as diverse, ambiguous and contradictory. For the rest, it constitutes a profound theme, to the point where one cannot dominate it as an object of analysis. At most, one can, through it, draw inferences and configurations, with a view to better understanding organizations, their components and dynamic (Bártolo-Ribeiro & Andrade, 2015; Santos, Gonçalves, Gomes, 2013; SantAnna, 2013; Chang, Yuan, Chuang, 2013; Carrieri, 2002).

According to SantAnna (2013), dealt with initially, within the ambit of studies on Organizational Behaviour, as the apprehension of flashes of elements apparent and manifest (Rozkwitalska, 2014; Hofstede, 1984; Fleury, 1992); and, subsequently, as investigation of latent and symbolic dimensions, from the perspective of Schein (1986), organizational culture can be comprehended as the set of basic presuppositions invented, discovered or developed by a group, as it learns to deal with the problems of external adaptation and internal integration functioning sufficiently well to be considered valid and transmitted to new people in the organization as the best way of perceiving, thinking and feeling the challenges presented to them (Fleury, 1992).

Later, other epistemological perspectives are applied, such as studies inspired by psychoanalysis (Pagés, Gaulejac, Bonetti & Descendre, 1987), as also those that start from the comprehension of culture as metaphor, proposing an analysis of the organization in symbolic terms and aspects, through the critical examination of its chain of discourse (Morgan, 1996). More recently, although a significant influence of the anthropological perspective is still seen, one has tried to incorporate into cultural studies, treatments of regulation, the standard and cognition (Carrieri, 2002).

2.3 Trust

In dealing with the problems of modernity, Giddens (1991) devotes a substantial part of his discussion to the dyad security versus danger and trust versus risk. For the author, trust is a specific type of belief that involves the attribution of "probity" (honour) or love, in the case of human beings, and, in the case of systems, in the correctness of the principles on which they are based – and of which one is ignorant – or on their functioning. According to this view, to investigate particularities of the relations of trust in national cultures, as well as their impact on the act of trusting, becomes an opportunity to throw some light on the ways that the relations are established in our reality. This knowledge can, in the framework of a global economy, become a precious instrument for the perfecting of management policies and practices.

In the world of business – conducted by formal contracts – many transactions occur because of the trust between the parties (Jiang & Probst, 2015; Vanhala & Dietz, 2015; Zanini, 2007). The imminent risk is absorbed by the strong relationship of trust, fruit of a social dimension, expressed in such a relationship, which is capable of resulting in cooperation between the agents.

Necessary for guaranteeing social institutions, trust is a phenomenon that has already been amply studied in the social sciences. In the organizational field, the studies are still recent, the interpersonal relationship having been understood as capable of generating trust between its members, contributing to the transfer of knowledge, productivity and cost reduction in transactions.

In general terms, such a relationship of trust emerges from the uncertainties of the economic life of the parties involved. Trust reduces such uncertainties, signalling actions of the current and future partner that are supported by the relationships of the present and the interactions of the past. It is therefore a relational device that reduces behavioural risks in the social system (Jiang & Probst, 2015; Vanhala & Dietz, 2015; Zanini, 2007).

In this way economic analysis sees trust as a subclass of the risk relationships. In organizations, the relationship of trust supersedes the formal contracts required by law and becomes a relational contract.

Within the ambit of the individual-work-organizations relationships, formal work contracts, in basing themselves on a relationship of long-term earnings and benefits, are, by definition, incomplete (Zanini, 2007), being typical examples of relational contracts. In addition, when trust is present the efficiency of contractual relationships increases, by avoiding controlling and monitoring bureaucracies that inhibit spontaneous cooperation and which incur transactional costs (Jiang & Probst, 2015; Vanhala & Dietz, 2015; Zanini, 2007). Trust is, therefore, fundamentally involved in the institutions and organizations of the modern world. Anyone who uses money and its equivalents does so on the presumption that the others, who he or she will never know, will honour its value. But it is not the money as such that one trusts, not only, or even primarily, but the persons, institutions and/or organizations with which the specific transactions are effected (Giddens, 2009).

3. Methodological aspects

To base the objectives of this study an empirical research of a qualitative nature was carried out (Collis & Hussey, 2005; Selltiz, Wrightsman & Cook, 1974; Triviños, 1987), conducted by means of a case study of the Portuguese organization, with its headquarters in the city of Oporto, and its Brazilian unit located in the city of Belo Horizonte.

Constituted in 1999, the researched multinational has as the focus of its activities the tertiary sector, specifically the licensing of information systems in health care institutions. Orientated by organizational values such as commitment to excellence, competence, transparency, generosity and love of life in all its forms, the company expanded its activities from Portugal into other countries such as Mexico, Spain, the United States, France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Singapore and Brazil.

The Brazilian subsidiary in Belo Horizonte enjoys the collaboration of managers and a professional body which is genuinely Brazilian, but at the beginning of its operations it had a strong contingent of Portuguese, who, although already repatriated, are regularly visiting the unit for the purposes of guiding and monitoring the work carried out.

It should be stressed that for the collection of data semi-structured and in-depth interviews were carried out with the managers of both units – Portugal and Brazil – responsible for the operation of the business area to which the subject of this study, the Brazilian subsidiary, is linked – as well as the analysis of secondary data on the units, obtained through its sites on the Internet and documents that it itself supplied. Mention must be made of the utilization of the interview script, arranged according to the following factors in the analysis: National Culture, Organizational Culture, Management Style, Professional Behaviour and Relationships of Trust.

Thus, 12 managers, 8 from the Brazilian unit and 4 from the head office, responsible for the business unit to which the Brazilian subsidiary is linked, were interviewed, and the testimonies obtained were recorded, transcribed and subsequently submitted to an examination using content analysis techniques, and the premises and techniques indicated by Bardin (2010).

4. Presentation, data analysis and findings

The main findings of the study, obtained from the set of reports relative to the managers investigated in both countries, were related to evidence of the perception of links between trust, the organizational culture, and specific traces of the contexts to which they are linked, especially those arising from historical, social, psychological and cultural conditions.

In fact, in deepening the analysis of the data set obtained it was possible to demonstrate phenomena that run through the management and human behaviour in the organizations, highlighting the cultural substrate in which organizational norms and values are supported in different cultures. The cultural dimension especially was greatly linked to the question of values, the various levels of work organization, of the policies and practices, of the layout, among the others that comprise cultural artefacts (Fleury, 1992), being less pronounced – or when present, associated with the values referred to.

Notwithstanding this, it was possible to detect perceptions in both countries, regarding the little investment in the collective building and socialization of its institutional values. Some respondents pointed to the lack of maturity in the discussion and dissemination of values and principles. Others even questioned their direct connection to work practice and daily routine, although the values have been institutionally formalized.

Also recorded was a certain resentment in the treatment perceived by Brazilian managers in relation to the values that are the foundation of the ruling culture, sentiments that denote perceptions regarding the unequal treatment , without any wider consideration of aspects concerning the values disseminated in the organizations formal discourse, for example the value attributed to meritocracy. Such perceptions regarding the non-internalization of the values and even a dichotomy between discourse and practice are also manifest in criticisms of the socialization process of organizational values – or in the absence of space and time for (re-) visiting the corporations values, giving them meaning, linking them to concrete cases that run through the whole daily routine of the Brazilian unit.

It must be placed on record in dealing with this subject, that the Portuguese managers, in bringing up the question of values, seem to do it – or are perceived so by the Brazilian managers –emphasizing more the Portuguese national culture than the culture of the company in itself and of the particular contexts in which it acts. As a consequence – and considering the historical past of the relations between the two countries, linked especially to the dyad colonizing power- colony – there is evidence of company culture representations strongly associated with terms like domination and control, frequently reinforced by the management style of the Portuguese leaders.

Although there are facilitating factors – like the common language – a veiled opposition between the Portuguese and Brazilian cultures seems to mark the substrate of the relations of the Brazilian subsidiary with its head office. At times explicit, with allegations about the difficulty of Portuguese managers in adapting to the characteristics of Brazilian national culture or – another side of the same coin – a tendency on the part of the Brazilian respondents, commenting on their own culture, to make comparisons that seem to provide feedback for an imaginary situation of conflict in the relationship.

For the rest it is important to stress the reduced emphasis of the organization on overcoming or deflating the ruling or historically produced ideals, through, for example, bringing into evidence organizational aspects capable of integrating on new bases the diversity contained in the organization. In other words, one cannot see any priority for the construction of local organizational environments that seek to articulate better the local and global and through this articulation build values collectively that are not only associated with specific national cultures, but that contemplate the richness of the diversity experienced in multicultural operations, and the universality anchored in common aspects that could comprise the raison dêtre, or the values of the corporation in itself.

One is not proposing, obviously, the construction of a culture such as that denounced by Pagés et al. (1987), that is, a hypermodern culture, dominating through pasteurization and internalization of a faceless control, with no origin; but of an organizational culture founded on conversations that highlight the diversity, the recognition of the other – alterity – just as it mobilizes purposes that transcend the internal conditions of any particular unit, connecting the different players, in different contexts. The conflicts, the contradictions are inherent, but also is subjectivity, the fundamental element in the constitution – or not – of social ties capable of uniting peoples and people, as humanity.

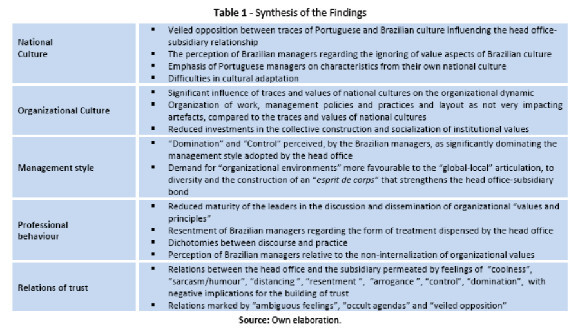

Table 1 synthesizes the principle findings obtained, according to the categories of analysis utilized in this study.

Based on this, in the next topic the analysis of the findings will be deepened and the final considerations presented, drawn up on the basis of the data obtained.

5. Final considerations

In a global context in which the notion of national state is continually threatened by the discourse surrounding the company state; in a contemporary world in which, not rarely, corporations can possess wealth and populations greater than many countries; articulations between the constructs of national culture and organizational culture are not without their purpose. On the contrary, the case studied can be indicative of the difficulties companies face, which come from countries in which precisely the tradition and the role of the state are placed at a higher level than those of the organizations in themselves.

This appears to be the case of Portugal. A small country, without extensive mineral and economic resources, that since its origins has fought and has known how to regiment its people in the service of a larger cause: to constitute a sovereign state, extending its space and overcoming its limitations, through the spirit of adventure and trail blazing (Meneses, 2007), but always with the expectation, after the conquest has been completed and the glories and riches obtained, of returning safely home.

This national unity, this union as a process of attenuating differences and consolidating affinities can, however lead to tendencies towards making uniform and distrust, especially in relation to what is not familiar, a term understood here in the sense of larger family, that for the Portuguese context seems very much linked to the notion of nation.

Risks, however, enter onto the scene regarding the super valuation of national culture, of the acculturation of what does not constitute this familiar, of forcing values that, rather than being of the undertaking in itself, belong to the larger family state, to the flag that represents them. At the same time that one is stripped in the sense of conquest, one is nostalgic in the sense of tradition, of the nation, of attachment to ones origins.

On the other hand, the Brazilian, who probably given the fragility of his founding myth, seems to have adopted the creation of intermediate paths – the jeitinhos (the unconventional solutions to problems), the good humour – that, for many, represents the genuinely Brazilian way of life, defining the way of relating the levels of the public and the private, the personal and the impersonal (DaMatta, 1983).

Going beyond its pejorative characteristic, the jeitinho – as well as malandragem (rascality) – could be interpreted as a strategy for dealing with difficult situations, without disclosing their inherent conflicts; of adaptation; of the search for regional, flexible, dynamic solutions. A particular way of dealing with the strange, with something that presents itself as a form of domination, of submission, of authoritarianism. In short, together with rank, the exercise of authority, the do you know who you are talking to?, a strategy of resistance (DaMatta, 1983; Meneses, 2007).

Such cultural universes so close in their origin, but at the same time so diverse in their evolution, if not mediated –through for example organizational culture – have implications for the issue of trust.

The primacy of national culture over the organizational can, equally, be called upon to explain the necessity of the Portuguese to salvage and reaffirm his value of pioneering agent and protagonist, avoiding contrary opinions, or have to face the possible dilemma of the son overtaking the father in some particular questions.

In concluding this analysis, focused on the similarities and differences between the two national cultures investigated and their potential impact on the constructs of Organizational Culture and Organizational Trust, it is relevant to register the characteristics that make the individual-work-organizations relationships manifest specific characteristics.

Other perspectives of analysis and questions, however, are placed before us. After all, whether one is in Brazil, Portugal, Germany or China, what would distinguish – in the Bourdieusian sense of the term – a company manager subject of the study from the others? Would it be something of the order of a mobilizing cause that would identify them as a group? Even if this cause seems today to be the same for all organizations – immediate profit, here and now – even so, because of this, what else could distinguish them? And further, as attributes of the national culture, their specific features, could they articulate with a view to adhere to this cause? In what way would their sharing forge ties of trust, cooperation and integration?

Under this line of reasoning, faced with the differences between the two cultures – manifested for example in the perception of Brazilian managers that the Portuguese are more direct and objective, what would be the result of a possible complementary nature of these diverse competences?

To reply to this set of questions brought up by our study is no simple task, however, the same findings seem to denote the relevance of (re) placing it on the agenda – above all in the case of Portugal, in which as a trace of its colonizing presence in Brazil there is evidence in the emphasis on miscegenation and syncretism – the importance of building organizing contexts in which meta-values such as the recognition of alterity, the recognition and respect for differences, the articulation of diversities, the sense of community and spirit of cooperation can form a front before the homogenizing logic of competition and the profit imperative at any cost, amply disseminated in the policies and practices anchored in Scientific Management.

In other words, the contemporary organizational models seem to prioritize a culture that could be described as one of a unique line of thinking, homogeneous, a symptom that exposes the necessity – or opportunity – of thinking about the prevailing culture in organizations from new angles. After all, how do you build organizational environments in which cultural and personal diversity can be effectively mobilized?

Data from the study revealed that the organizational structure of the Brazilian unit is established along the same lines as the Portuguese head office, although the Brazilians tend to see and express differences, or even cover them up, in particular when they assume managerial positions. In this case, the testimonies even stress the adoption of typical behavioural patterns – if not more pronounced, similar to the stories about the not rare brutality of slaves who become masters – of the managerial style of the Portuguese.

If for the Portuguese interviewees, the Brazilians are calmer than the stressed and agitated Portuguese manager, would this not be, to say it again, a question of considering such a difference as an important complementary factor? In fact up to what point it is not the national culture in itself, but rather the absence of a strong organizational culture, the factor that explains many of the contradictions, paradoxes, diasporas and conflicts underlying the organizational dynamic under analysis?

Notwithstanding the limitations of this study, such as the reduced number of respondents, as also the option for the case study method, it is suggested that a survey contemplating a greater range of companies from the two countries be carried out, but also that it should be complemented by qualitative methods and techniques, such as interviews and image evoking techniques. Instead of verticalizing only one company, a wider-ranging survey would allow one to delineate a wider panorama of how different managers, in distinct companies and geographical areas of the two countries investigated - Brazil and Portugal – experience the relations between these important constructs: Culture - national and organizational - and Trust - inter and intra organizational – contributing to an expansion of the data and the line of studies on the theme.

References

Azevedo, R. (1958). A cultura brasileira: introdução ao estudo da cultura no Brasil. São Paulo: Melhoramentos. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2010). Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Bártolo-Ribeiro, R. & Andrade, L. J. (2015). Expatriates Selection: An Essay of Model Analysis. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 3(1), 47-57. [ Links ]

Buarque, C. (1990). A desordem do progresso. São Paulo: Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Carrieri, A. P. (2002). A cultura no contexto dos estudos organizacionais: breve estado da arte. Organizações Rurais & Agroindustriais, 4(1), 38-50. [ Links ]

Chang, W. W. Yuan & Chuang, Y. T., (2013). The relationship between international experience and cross-cultural adaptability.International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(2) 268– 273. [ Links ]

Collis, D. J. & Hussey, R. (2005). Pesquisa em administração. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

DIribarne, P. (1989). La logique de lhonneur: gestion dês entreprises et traditions nationales. Paris: Point, Editions de Seuil. [ Links ]

DaMatta, R. (1983). Carnavais, malandros e heróis: para uma sociologia do dilema brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar. [ Links ]

Fleury, M. T. L. (1992). O desvendar a cultura de uma organização: uma dimensão metodológica. In: M. T. L. Fleury & R. M. Fischer (Orgs.). Cultura e poder nas organizações. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: self and society in the late modernity age. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (2009). The politics of climate change. New York: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultures consequences: international differences in work-related values. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Holanda, S. B. (1984). Raízes do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio. [ Links ]

Jiang, L. & Probst, T. M. (2015). Do your employees (collectively) trust you? The importance of trust climate beyond individual trust.Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(4), 526-535. [ Links ]

Laurent, A. (1981). Cultural View of Organizational Change. In Evans, P. Doz, Y. and Laurent, A. (Eds), Human Resource Management in International Firms (pp. 83-84). London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Leana, C. R. & Burren, H. J. V. (1999).Organizational social capital and employment practices.Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 539-555. [ Links ]

Meneses, A. F. (2007). Portugal é o mar. Açores: Universidade dos Açores. Azores: University of the Azores. Retrieved 13 August 2013 from https://repositorio.uac.pt/handle/10400.3/628. [ Links ]

Moraes, L. F. R. (2007). Valores no trabalho e suas interfaces com algumas variáveis do comportamento organizacional (Relatório de Pesquisa/2007).Pedro Leopoldo, MG, Faculdade Integrada de Pedro Leopoldo. [ Links ]

Morgan, G. (1996). Imagens da organização. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Motta, F. C. P., & Caldas, M. P. (1997). Cultura organizacional e cultura brasileira. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Nery-Kjerfve, T, McLean, G. N. (2015). The view from the crossroads: Brazilian culture and corporate leadership in the twenty-first century. Human Resource Development International. 18(1), 24-38. [ Links ]

Pagés, M., Gaulejac, V., Bonetti, M., & Descendre, D. (1987).O poder das organizações. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Paula, C. P. A. (2005). O símbolo como mediador da comunicação nas organizações: uma abordagem junguiana das relações entre a dimensão afetiva e a produção de sentido nas comunicações entre professores do departamento de psicologia de uma instituição de ensino superior brasileira. (PhD thesis). Instituto de Psicologia. São Paulo. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, D. (1995). O povo brasileiro: a formação e o sentido do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Rozkwitalska, M. (2014). Negative and Positive Aspects of Cross-Cultural Interactions: A Case of Multinational Subsidiaries in Poland. Engineering Economics. 25(2), 231-240. [ Links ]

SantAnna, A. S. (2013). Cultura organizacional. In F. O. Vieira, A. M. Mendes & A. R. C. Merlo (Orgs.). Dicionário crítico de gestão e psicodinâmica do trabalho. Curitiba: Juruá. [ Links ]

Vieira, F. O., Mendes, A. M. & Merlo, A. R. C. (Orgs.). (2013). Dicionário crítico de gestão e psicodinâmica do trabalho. Curitiba: Juruá. [ Links ]

Santos, J., Gonçalves, G. & Gomes, A. (2013).Organizational culture and subjective and work well-being.The case of employees of Portuguese universities, Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 1(3), 153-161. [ Links ]

Schein, E. B. (1986). Organizational culture and leadership: a dynamic view. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Segnini, L. R. P. (1988). A liturgia do poder: trabalho e disciplina. São Paulo: EDUC- PUC. [ Links ]

Selltiz, C. Wrightsman, L. S., Cook, S. (1974). Métodos de pesquisa nas relações sociais. São Paulo: EPU. [ Links ]

Triviños, A. N. S. (1987). Introdução à pesquisa em ciências sociais: a pesquisa qualitativa em educação. São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Vanhala, M. & Dietz, G. (2015). Trust in Employer and Organizational Performance. Knowledge & Process Management, 22(4), 270-287. [ Links ]

Zanini, M. T. (2007). Confiança: o principal ativo intangível de uma empresa. Trust: a companys main intangible asset. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 07.07.2015

Received in revised form: 12.01.2016

Accepted: 15.01.2016