Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.2 Faro jun. 2017

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Foreign training in Jordan's international hotel chains: a quantitative investigation

Formação fora do país em cadeias hoteleiras internacionais da Jordânia: uma Investigação quantitativa

*Samer Al-Sabi, ** Mousa Masadeh, *** Bashar Maaiah, **** Mukhles Al-Ababneh

*Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, College of Archaeology, Tourism & Hotel Management, Petra, Jordan, sa.alsabi@gmail.com

**Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, College of Archaeology, Tourism & Hotel Management, Petra, Jordan, jordantourism@hotmail.com

***Yarmouk University, The Faculty of Tourism and Hotel Management, Irbid, Jordan, profalhussain@yahoo.fr

****Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, College of Archaeology, Tourism & Hotel Management, Petra, Jordan, mukhles.ababneh@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This paper draws on the perceptions of middle managers in Jordan to identify what determines upper management's decision in International Hotel Chains (IHC) to invest in out-of-country training (OCT). A model employing the presence of relationships between ‘attitudes', ‘benefits and usefulness', ‘barriers' and ‘IHC's decision' to invest in OCT, was proposed and examined. A total of 261 middle managers from IHCs in Jordan provided responses to a structured survey. Confirmatory factor analysis validated the dimensions for each construct. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the relationships among the four constructs of the study. The results showed a direct relationship between attitudes and benefits/usefulness to IHC's decision to invest in OCT, and demonstrated the mediating role of attitudes in the inverse relationship between barriers and IHC's decision to invest in OCT.

Keywords: International hotel chains, out-of-country training, middle managers, hotel management practices, Jordan.

RESUMO

Este artigo baseia-se na percepção dos gerentes de nível médio na Jordânia para identificar o que determina a decisão da gerência de topo das Cadeias Hoteleiras Internacionais de investir em treinamento fora do país. Foi proposto e examinado um modelo que emprega a presença de relações entre "atitudes", "benefícios e utilidade", "barreiras" e "decisão das Cadeia Hoteleiras Internacionais" de investir em formação no estrangeiro. Um total de 261 gerentes médios de IHCs na Jordânia deram respostas a uma pesquisa estruturada. A análise fatorial confirmatória validou as dimensões de cada construto. A modelagem de equações estruturais (SEM) foi utilizada para testar as relações entre as quatro construções do estudo. Os resultados mostraram uma relação direta entre atitudes e benefícios / utilidade para a decisão da IHC de investir na formação no estrangeiro e demonstraram o papel mediador das atitudes na relação inversa entre as barreiras e a decisão das Cadeias Hoteleiras Internacionais de investir na formação fora do país.

Palavras-chave: Cadeias hoteleiras internacionais, formação fora do país, gestores intermédios, práticas de gestão hoteleira, Jordânia.

1. Introduction

It has been increasingly recognized that human resource development (HRD) and training are essential to achieving organisational goals (Burma, 2014; Marchington & Wilkinson, 2002; Burma, 2014; Banerjee, 2016; Chand, 2016; Phillips and Phillips, 2016). However, there is presently little research devoted to HRD and training specifically in the hotel and tourism sector (Aktas et al., 2001; Conrady and Buck, 2008; Chand, 2016, Madera et al., 2017). Furthermore, little research has been devoted to training of middle managers in the hospitality industry, despite their pivotal role in the success of a hotel business. Middle managers often act as intermediaries between upper management and front-line staff and offer distinctive insights into their organisations' training and business management practices. Given that management positions involve specialised training requirements, the need for middle management training programmes in chain hotels to respond to future needs and personnel potential is high (Boella & Goss-Turner, 2005; Ramos, Rey-Maquieira and Tugores, 2004; Kuruüzüm, Anafarta and Irmak, 2008; Chand, 2016). Since international hotel chains (IHCs) are dominant in today's global hotel markets (Pine & Qi, 2004; Kim et al, 2011), and middle managers are the likeliest of their employees to receive training, which in some cases takes place out of the country, the present research study aims to identify what determines the decision of the top management in IHCs to invest in middle managers' out of country training (OCT). Specifically, this article investigates the perceptions of and experiences with OCT among middle managers in IHCs in Jordan, where a robust and expanding tourism industry plays a major role in economic development.

The Case of International Hotel Chains in Jordan

Despite its small size, small economy and scarcity of natural resources, Jordan has, remarkably, achieved significant economic and social development. The country's natural attractions help draw large numbers of tourists year-round. Jordan's median geographical location, moderate climate, topographic attributes, and diverse regions (the Dead Sea, oriental mountains and other areas spread across the country) make the country a desirable destination. Moreover, Jordan boasts a number of famous historical sites, including the Nabataean city of Petra, which was designated one of the new Seven Wonders of the World in 2007.

In Jordan, the tourism sector has contributed substantially to the welfare of the country's economy, helping to upgrade the balance of payments and inject foreign currency into the country. In 2011, the contribution of tourism to the kingdom's overall GDP was estimated at 11 per cent (Central Bank of Jordan, 2011) - approximately double the global average. Through investment incentive legislation, the Jordanian government encourages Arab and foreign investors to augment hotel development and investments, leading to a greater influx of tourists and foreign currency. Consequently, the number of hotels has increased from 349 hotels in 1997 to 497 hotels (classified & unclassified hotels) in 2011. The number of employees in different tourism activities reached around 21,293 in 2002, 29,384 in 2005, and 41,879 in 2011, climbing to 50,476 in 2016.

IHCs play a role in enhancing development in the countries where they invest (Kim, Erdem, Byun & Jeong, 2011) and provide various opportunities in developed and developing countries for reducing unemployment and creating jobs, since they employ considerably higher numbers of employees compared to local hotels. In Australia, for instance, two-thirds of hotel accommodation is dominated by IHCs (Timo & Davidson, 2005).

In Jordan, thanks to globalisation and the Jordanian government's continuous support, the number of IHCs has increased remarkably since 1990, from 5 to 29 hotels (The Jordanian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, 2016).

The case of OCT for IHCs' middle managers

IHCs are frequented by international clientele who would expect certain standards, services and treatment just like they would get at home, and one could argue that OCT training for their staff is particularly pertinent. Middle managers - being intermediaries between top management and the local hotel staff - are the ones who could transmit values, standards and rules that comply with the international standards, thus it seems logical that they should be the ones selected for OCT.

Nevertheless, several questions arise: how is OCT perceived among middle managers? Does such training benefit the hotel and the individual? What are the barriers of implementing OCTs? How do middle managers get selected for OCT? These questions prompted research in this topic with the goal in mind that the results would be beneficial for decision-making for IHCs' top management as well as for policy makers in the country. Furthermore, the results could be applied in other developing countries in similar context.

2. Literature Review

The role of middle managers has been explored in various literature, though not specifically within the hospitality industry. IHCs are dominant in today's global hotel markets (Pine & Qi, 2004; Kim et al, 2011), and middle managers are the likeliest employees to receive OCT. Creelman (1995: 6) portrays middle managers as “the oil that lubricated the top-down flow of corporate commands and information …who ensured the smooth running of the company. Take them out and the engine would fail.” Denham, Ackers and Travers (1997) also stress middle managers' key function as intermediaries in the administration.

Middle managers' strategic role in transmitting information within the company's hierarchy has been recently studied; for example Rouleau and Balogun (2011), through a study of discursive activities, confirm that middle managers are able to influence their subordinates, seniors and peers. The need for middle management training programmes in chain hotels-has been reported by a number of studies (Garavan, 1997; Boella & Goss-Turner, 2005). Ramos, Rey-Maquieira and Tugores (2004), Kuruüzüm, Anafarta and Irmak (2008), for instance, report a high demand for middle management training in high-quality hotels.

In Jordan, where IHCs' senior management is often expatriate, middle managers generally come from within the region, and are therefore logical candidates for training in Western countries. It is argued that since many developing countries lack the infrastructure to conduct local training for hotel staff, OCT in these regions is of particular significance. Among other benefits, OCT is supposed to help managers acquire exposure to other cultures (McCarthy, 1990) which would be beneficial in an IHC. Moreover, Terterov (2004:130) indicated that there is a ‘real value' achieved through training outside the local environment of developing countries; “Provincialism in taste seems to respond most quickly and thoroughly to this kind of experience. Couple that with the benefits associated with high qualifications and the staff begin to resemble what the modern history demonstrated.”

IHCs would benefit from a greater emphasis on training abroad, which serves to expose managers from developing countries to the latest industry techniques and ‘best practices' (Ladkin & Juwaheer, 2000.) These practices can then be passed on to subordinates and enhance managers career potential within an organisation (Rowley and Purcell, 2001). It has been argued that training abroad can serve as a motivator that often leads managers to be more effective in their work (Tsang, 1994; Analoui, 1999).

An alternative approach to training hotel staff abroad is the view that expatriate managers endowed with western management are necessary for training local staff (Littrell, 2002), as it has been stated that the training programmes carried out by expatriate trainers are profitable and work to the hotel's advantage (Wang, 2011). However, training techniques and methodological and pedagogical models imported from western countries do not always serve the needs of employees in developing countries (Huyton & Ingold, 1999; Magnini & Ford, 2004). The training methods and educational systems of Jordan cannot be equated to those of Britain or the USA. For example, Galagan (1983) argued that transferring training methods from developed countries to less developed countries would not succeed, recommending instead that the best way to learn about training methods is by going abroad.

The link between training and development and employee job satisfaction, loyalty, and intent to stay was explored by Costen and Salazar (2011) who conducted a research with employees at four luxury hotels in the USA. Even though their research did not target middle managers, their findings are interesting in terms of showing that the opportunity to participate in training and the opportunity for career advancement positively influence an employee's job and company satisfaction, and lead to stronger attachment to the hotel.

One study that dealt particularly with training abroad and foreign replacements was conducted by the German Federal Institute for Vocational Training. The short report entitled “Study highlights benefits of foreign placements for young trainees”, (German Federal Institute for Vocational Training, 2003) indicates that training abroad is beneficial for trainees as well as for their employees. In the study, when trainees were asked about the major obstacles encountered in connection with training and working abroad, the following were the most prevalent: lack of money, lack of adequate language skills as well as lack of appropriate contacts; when companies were asked the same question, they cited financial costs as the key obstacle to training abroad.

Another interesting research was conducted in Chinese four and five-star hotels (four state-owned and four Sino-foreign joint-venture/chain) that explored training and development and human resources (HR) practices through interviews with senior-mangers, middle-managers and HR managers (Wang, 2011). The author observes that in joint-venture hotels the HR practices were more systematic and consistent, being able to use the expertise of their foreign parent hotels. However, interestingly, the four state-owned hotels (only one of them is a chain-hotel) actually reported having used OCT with less success and invited foreign experts to teach in their hotels. The four joint-venture hotels did not apply the OCT method, rather training was carried out by personnel or trainers from their parent companies. This study suggests that chain hotels that have foreign partners have more expertise in HR and more resources (trainers) to carry out training within the country.

3. Hypothesis and Proposed Model

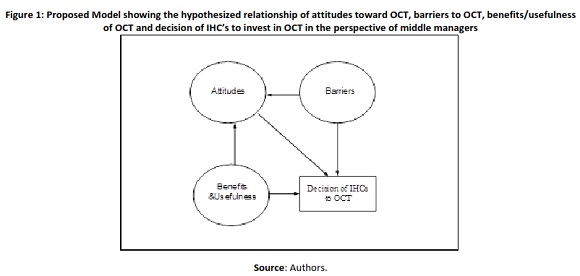

It was hypothesised that the IHC's decision to invest in OCT is influenced by top management's attitudes towards the benefits and usefulness derived from the training and the barriers encountered in sending employees for OCT. A model employing the presence of relationships between ‘attitudes', ‘benefits and usefulness', ‘barriers' and ‘IHC's decision' to invest in OCT, is proposed and examined.

The model proposes that the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT for their managers depends on three major factors: benefits and usefulness of OCT, barriers encountered and attitudes towards OCT. Moreover, the attitude of the IHC is affected by the barriers encountered as well as the benefits and usefulness of OCT. Figure 1 depicts this assumption. The decision of the IHC to invest in OCT is represented by a rectangle because it is an observed variable. The other variables such as attitude, barriers encountered, and benefits/usefulness of OCT are represented by ellipses because they are latent variables, which cannot be measured directly, but through their defined dimensions or attributes.

4. Methodology

A total of twenty-nine hotels accepted the invitation to participate in the study. Most of the participating hotels were five-star hotels (according to the Jordanian Ministry of Tourism classification and star ranking). Nine middle managers for each of the twenty-nine IHCs were targeted as respondents to a structured survey questionnaire.

Managers in key function departments, such as human resources, food and beverages, accounting and finance, front office, housekeeping, sales and marketing, purchasing, engineering, banqueting and others, in all IHCs listed by the Jordan Hotel Association were included. In order to obtain a wide representative sample in this census study, the questionnaire was designed to include middle managers in the four main tourist cities in Jordan (Amman, Aqaba, Petra, Dead Sea), which contain all the IHCs.

The 261 questionnaires were distributed to managers between 23 May and 28 July 2007, in person by the researcher. The reason for using a manually-distributed over an electronically-distributed questionnaire was that response rates in mail surveys are known to be low (Harzing, 1997), especially in the developing world, because people often still do not have Internet access or do not possess e-mail facilities. Moreover, some managers reported a preference for manual distribution. Follow-up reminders by telephone were carried out to increase the response rate.

The survey questionnaire comprised of both closed and open-ended questions, in order to allow expansions of the managers' views. A ‘forward-backward' translation procedure was used; the questionnaire was translated into Arabic and the version then was translated back into English again by two different translators, who are fluent in both languages and who had not seen the original English questionnaire, to evaluate its validity and to ensure accurate translation. The questionnaire was also reviewed by two academics in the field of study for reliability. The final translated questionnaire was pre-tested for appropriateness of the questions as well as the instrument's ease of use, clarity, length and succinctness on a sample of twenty volunteer assistant department heads who agreed to take part and who were not involved in the study. In addition, in order to assess the construct's reliability, the corresponding Cronbach's alpha values were obtained. Each of the five constructs had an acceptable Cronbach's alpha value of over 0.70.

The 10-page questionnaire designed in this study consisted of eight main sections that included general questions about respondents' experience, knowledge and attitudes towards OCT; questions around management and company attitudes towards OCT; and questions around the main benefits as well as barriers to OCT. Six-point Likert-scaled responses were provided and the available choices ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree (1= strongly disagree; 2= disagree; 3= partially disagree; 4= partially agree; 5=agree; 6= strongly agree). Open-ended questions to allow managers to expand on their views as well as to allow the opportunity to share any other comments or suggestions they might have had about OCT which may had not been captured by the response categories were also included. The questionnaire also gathered demographic information for the respondents.

In addition to descriptive statistics, a series of data analyses were carried out including exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM). Each question was coded and assigned a variable name on the data sheet. The statistical analysis package SPSS 15.0 was used to analyse the data.

The data analysis took place in two stages following the approach of Anderson and Gerbing (1988). In the first stage, (EFA) was used to reduce the number of factors to be used as indicators to measure the three latent constructs: barriers, usefulness and benefits and attitudes. In the absence of any theoretical knowledge about the constructs of study, EFA is widely used as the preferred analytical technique to explore the underlying dimensions of the construct of interest by grouping similarly structured factors together (Hair et al, 2006).

The reliability and internal consistency of the items constituting a single dimension were evaluated by Cronbach's alpha coefficient. All questionnaire variables studied have alpha coefficients, ranging between 0.703 and 0.966 which demonstrates acceptable internal consistency, and were therefore retained for further analysis.

The dimensionality of measurement scales was assessed by unweighted least squares, with Varimax with Kaiser Normalisation. At this stage, based on the Kaiser criterion, the researcher chose to retain only the factors corresponding to eigenvalues greater than 1 rule (Kaiser 1958 cited in Hair et al 2006); then, the Scree plot was evaluated to ascertain that the same number of factors identified by the Kaiser criterion were produced. At the end, EFA allowed us to identify, respectively, 4, 3 and 3 factors corresponding to the original scales. Labelling of the factors was carried out by the researcher. Varimax rotation was then chosen to facilitate the interpretation of factors as one of the orthogonal factor rotation criteria (Varimax, Quatrimax, and Equamax) and deemed the most common and the most widely used method in the literature.

In the second stage, the process followed two steps:

In the first step CFA was carried out on the proposed model using the reduced number of factors as indicators to confirm the validity of the factors identified by EFA for each construct of study. At the end of this step, the meaningfulness of all indicators to their constructs was significant. CFA was conducted using AMOS 6.0.

In the second step, in order to test goodness of fit between the data and the proposed model, based upon the principle of maximum likelihood (ML) estimation, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted on the data with AMOS 6.0. These models provide gamma regression coefficients (γ) to understand the relative weight of each variable in explaining the perception the particular middle manager has of OCT. Additional research on the tourism and hospitality industry has shown the relevance of using structural equation methods to model the relationships between different variables (Davidson, 2000; Al-Hammad, 2006; Mohsin, 2007).

Retaining all of the factors and constructs, analysis proceeded according to the method advocated by Hair et al (1998): studying the fit of the overall structural model. In this step, successive tests were used to determine the best model for measuring variables of the research according to the indicators mentioned.

5. Results

Descriptive Statistics

A response rate of 79.3 per cent (207 questionnaires) was achieved. The profile of respondents reveals that the hotel industry in Jordan is male dominated at the middle management level, with 33 females (16 per cent) and 174 males (84 per cent). The majority of the respondents (46.4 per cent) were 30-39 years of age. In terms of years of management experience of the respondents, 21.3 per cent had 3-5 years of experience; 20.8 per cent had 10-15 years; 17.9 per cent had 1-2 years and 6-9 years, respectively; 12.6 had less than one year, and 9.7 had more than 15 years of management experience. The majority of the respondents were in their current workplaces for 1-5 years, indicating that most middle managers do not stay long in the same hotel. Only 5.8 per cent had been at their current hotel for more than 15 years.

Hypothesis Testing

Figure 1 shows the proposed model, in which five relationships between variables were hypothesised. This study involves empirical scientific testing and in the process, statistical decisions had to be made. The hypotheses were tested at a 95 per cent confidence level.

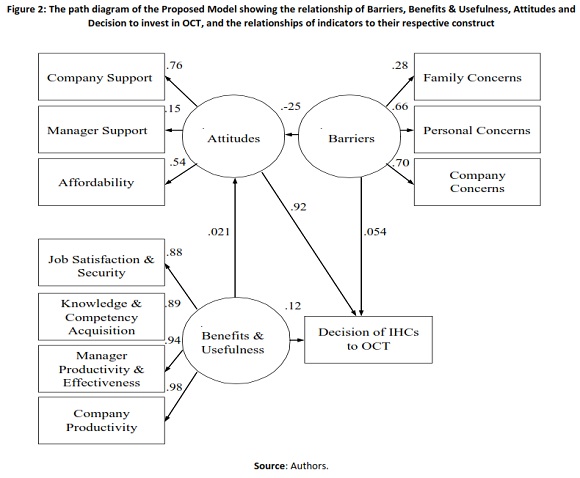

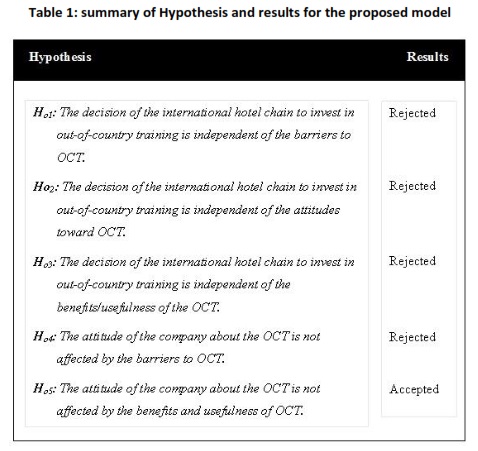

Figure 2 shows the results presented in path diagram format. Analysis of the results reveals that the data significantly fit the postulated structural model (RMSEA = 0.098; CFI = 0.92 and GFI = 0.91), indicating that any inferences drawn from the results of the investigation are reliable for the purposes of the present study. Table 1 summarises the results of hypotheses testing. The results showed direct relationships of attitudes and benefits/usefulness to IHC's decision to invest in OCT, and demonstrated the mediating role of attitudes in the inverse relationship between barriers and IHC's decision to invest in OCT.

While the overall chi-square test was statistically insignificant (x2 = 243.96, p<0.05), an acceptable model fit as far as RMSEA (0.098), GFI (0.91) and CFI (0.92) was shown by the model. The appropriateness of the x2 statistic has faced serious criticism due to its strong dependence on sample size (Marsh, Balla & McDonald, 1982; Marsh, Balla & Hau, 1996).

A) The relationships among barriers, benefits and usefulness, attitudes and the decision of IHC's to invest in OCT were tested as postulated.

Ho1: The decision of the IHC to invest in OCT is independent of the barriers to OCT.

Ho2: The decision of the IHC to invest in OCT is independent of the attitudes toward OCT.

Ho3: The decision of the IHC to invest in OCT is independent of the benefits/usefulness of OCT.

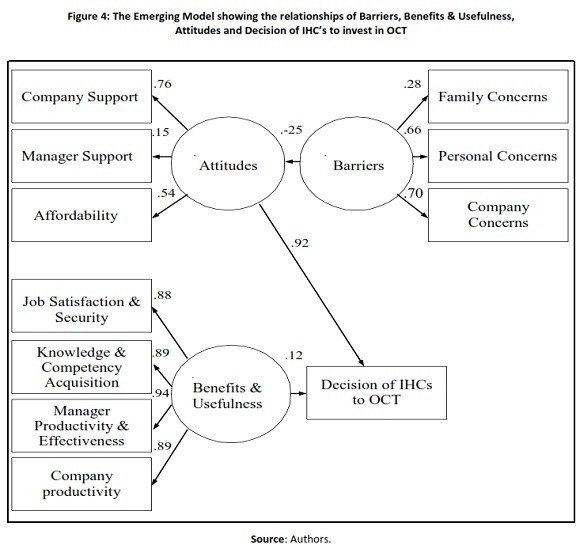

‘Barriers' is the first latent variable postulated as a determinant of IHCs' decision to invest in OCT. As shown in Figure 2, three variables emerged as significant indicators of barriers to OCT. The three variables along with the corresponding standardised coefficients are: family concerns (.28; p<.05), personal concerns (.66; p<.05), and company concerns (.70; p<.05).

‘Attitudes' is another latent variable hypothesised to be an important determinant of IHCs' decision to invest in out-of-country training. The data from Figure 2 show that all the three variables as proposed emerged as significant indicators of attitudes, namely: company support (.76; p<.05), manager support (.15; p<.05), and affordability (.54; p<.05).

‘Benefits/usefulness' is the next latent variable hypothesised as a determinant. The data in Figure 2 show that benefits/usefulness has four significant indicators including job satisfaction and security (.88; p<.05); knowledge and competency acquisition (.89; p<.05); manager productivity and effectiveness ( .94; p<.05); and company productivity ( .89, p<0.05).

Further analysis of the data (Figure 2) reveals that each path coefficient from attitudes and benefits/usefulness to decision of IHC to invest in OCT is significant (.92 and p<.05 for attitudes; .12 and p<0.5 for benefits/usefulness). This means that, according to middle managers, the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT is directly associated with the attitudes of the hotel management and the benefits/usefulness of OCT. Thus, it can be inferred that, from the respondents' perspective, the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT depends on the support of the company, managers' (i.e., potential trainees) support, capacity of the company to provide financial support for the managers, and the capacity of the managers to go abroad. Moreover, the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT depends on the perceived benefits/usefulness of OCT such as job satisfaction and security of managers, knowledge and competencies acquired by managers, productivity and effectiveness of managers, and company productivity. The path coefficients of attitudes and benefits/usefulness on the decision of IHC to invest in OCT were positive (.92 and .12, respectively), suggesting a greater likelihood that IHCs with highly positive attitudes about OCT, and the belief that OCT is beneficial/useful to the managers and hotel as a whole, would invest in OCT. Not surprisingly, likewise, it is inferred that IHCs with negative attitudes and beliefs about OCT would decline to invest in OCT.

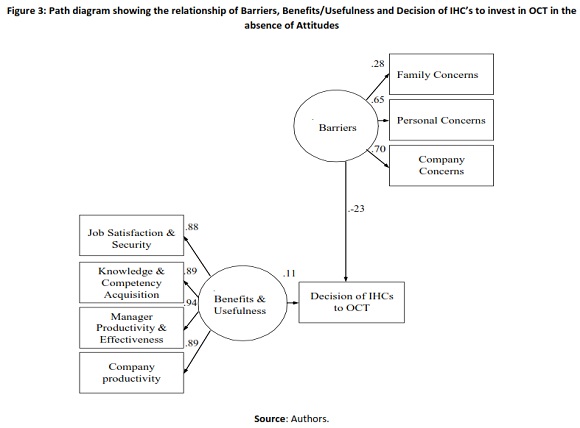

Further scrutiny of the data (Figure 2) reveals that ‘barriers' do not significantly affect the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT (.05, p>.05), but do significantly affect the attitudes (-.25, p<.05). However, the direct effect of barriers on decision of IHCs to invest in OCT became significant (-.23, p<.05) when the ‘attitudes' construct was excluded in the structural model (see Figure 3). Such findings indicate that mediation is present in the model (Baron & Kenny, 1986; and Judd & Kenny, 1981). That is, the effect of barriers on the decision of IHCs to OCT was mediated by attitudes. Thus, it can be inferred that the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT is dependent on the barriers to OCT such as family and personal concerns of managers, and company concerns, but this dependency is mediated by attitudes. The negative path coefficient of barriers on attitude indicates that the attitudes of the managers and hotel management were adversely affected by the barriers to OCT. The unfavourable direct effects of barriers on the attitudes of the managers and hotel management would lead hotel companies to decline to invest in OCT.

B) The test of dependence of attitudes on barriers and usefulness/benefits was carried out to confirm the hypotheses as postulated.

Ho4: The attitude of the company about the OCT is not affected by the barriers to OCT.

Ho5: The attitude of the company about the OCT is not affected by the benefits and usefulness of OCT.

The analysis revealed that barriers are negatively associated with the attitudes of the managers and hotel management-that is, managers and hotel companies who perceived barriers to OCT had negative attitudes about OCT, while those who perceived no barriers had more positive attitudes. Thus, decisions of IHCs to invest in OCT are affected by the barriers to OCT such as family, personal, and company concerns.

Further examination of the data (Figure 3) reveals that the path coefficient from benefits/usefulness to attitudes is statistically nonsignificant ( -.02, p>.05), suggesting that ‘attitudes' is not affected by the benefits/usefulness of OCT

The Emerging Model

The emerging model is as follows: First, the decision of the IHC to invest in OCT is dependent on the benefits/usefulness of the OCT and the attitudes of the company and managers. The attitudes construct is measured based on company support, manager support, and affordability, while the benefits/usefulness construct is measured based on job satisfaction and security of managers, knowledge and competencies acquired by managers, manager productivity and effectiveness, and hotel productivity. Second, the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT is dependent also on the barriers to OCT, but the effect of barriers on the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT is mediated by the attitudes of the managers and hotel management. Thus, barriers (such as family, personal and company concerns) directly affect the attitudes of the managers and hotel management as a whole. Third, the attitudes of the managers and hotel management towards OCT are not affected by the benefits/usefulness of the OCT, contrary to the proposed model.

Figure 4 depicts the graphical display of the emerging model. The model shows the absence of a direct relationship between barriers and the decision to invest in OCT as the relationship between the two constructs of the study is mediated by attitudes. The model also describes the direct effects of attitudes and benefits/usefulness on the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT, while the barriers construct has a direct but inverse effect on attitudes.

6. Discussion

This study aimed to identify the determinants of IHCs' decisions in regards to investing OCT, as perceived by middle managers, and in the process, provide a framework that can be used as a springboard for further study. Specifically, this study examined and analysed the relationship among attitudes toward OCT, the benefits and usefulness of OCT, barriers to OCT and the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT in Jordan's hotel industry.

The findings of the research study provide insights into the relationship between barriers to OCT, benefits/usefulness of OCT, attitude towards OCT and decision to invest in OCT constructs. As there have been no studies done in the past on IHC's OCT, despite its recognised importance in the business world, this research work was conducted to help illuminate some fundamental concerns regarding international training in the hotel industry.

Findings suggest that attitudes of the hotel management toward OCT, benefits/usefulness of OCT and barriers are the three true antecedents of IHC's decision to invest in OCT. However, the emerging (estimated) model surprisingly highlights the mediating roles of attitude in the impact of barriers on IHCs' decision, as opposed to the author's proposed model showing a direct effect of barriers on IHCs' decision to invest in OCT.

The results of the investigation reveal two major differences between the proposed model and the emerging (estimated) model. First, the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT is dependent on the barriers to OCT, but the effect of barriers on the decision of IHCs to invest in OCT is mediated by the attitudes of the managers and hotel management. Thus, individual barriers, such as family and personal concerns, directly affect the attitudes of the middle managers, while company concerns directly affect the attitudes of the top management. Consequently, barriers indirectly influence the company's decision to invest in OCT.

Second, the study shows that, according to respondents, the attitudes of the managers and hotel management concerning OCT are not, in any way, affected by the benefits/usefulness of the OCT. The middle managers, who were the respondents, perceived that the true benefits and usefulness of training do not have a major impact on the top management attitudes. This contradicts the literature, which argues that the top management's decision is influenced by the anticipated improvement of the middle managers' competencies and capabilities, something that would translate to improved performance and more profits for the company.

This research study substantiates the notion that attitudes toward OCT and benefits and usefulness have direct positive effects on the decision of IHCs in Jordan to invest in OCT for middle managers, supporting the proposed framework of the author. If financial constraints remain the major concern preventing hotel companies from sending middle managers for OCT, then the author agrees with Taylor and Berger (2000) that in the future, on-the-job training (OJT) will emerge as the most prominent form compared to other training methods. Because OJT is conducted on-site with employees at the workplace, it may, among other possible perceived benefits, be significantly more cost efficient for hotels. OJT is also associated with increasing productivity and offers an efficient means for upgrading employees' skills, besides costing much less than off-site training (Read and Kleiner, 1996). An overwhelming majority of hotel companies employ this method (Aktaş et al, 2001), most of which in fact use OJT as the sole form of training (Harris, 1995), and may even be seen as relying too heavily upon it (Barrows, 2000). Among other training approaches, OJT has been noted as the single most important (Ramos, Rey-Maquieira and Tugores, 2004), and as a key element in successful hotel food and beverage management (Nebel, Braunlich and Zhang, 1994).

As the cost of sending employees on training is prohibitively high, the IHC's top management will in all likelihood remain adamantly opposed to sending middle managers for international training, unless some clear connections are established between this kind of training and business performance and profitability. As with any type of investment, the return on investment is one of the key criteria to consider. As Garavan, Heraty and Barnicle (1999) found, the link between investment in HRD and organisational performance was difficult to establish. Likewise, as Baum, Amoah and Spivack (1997) report, HRD has not gained full recognition in the hotel and tourism industry as a major factor in the delivery of quality customer service and products. So far there are no available studies in the literature that clearly define a link between HRD and hotel performance.

In terms of implementing more comprehensive measurements of return on investment for hotel training programmes, Farrell (2005) has advocated a greater focus on non-monetary factors such improved employee behaviour, reduced turnover rates and higher customer satisfaction. He argues that an emphasis on revenue changes alone, to the exclusion of these factors, provides an incomplete picture of the value of employee training programmes for hotels. Kline and Kimberly (2008), likewise, found in a study of lodging managers that, although training constitutes a major expense of the industry, there are insufficient mechanisms in place to reliably account for this spending in terms of return on investment. In addition, training should be viewed as a long-term investment which may take several years to pay off. Moreover, the authors note that very little research on the topic has been conducted with managers in hotels.

It has been noted that the hotel's top management's major concerns pertaining to training people are the financial requirements, high costs and the fear of the unknown. These factors significantly determine the decision of IHC's to invest in OCT. This research suggests that middle managers should be made aware of the issues that the company faces in terms of sending middle managers to international training, and need to develop and demonstrate the loyalty necessary to assure upper management of their timely return and continued, long-term employment in the hotel following training. In addition, employees should seek first to contribute to the betterment of the company to prove to the top management that they are indeed valuable assets of the hotel; in so doing the top management might view their employees' professional development and growth as an investment in the company's future. Other barriers to training, such as personal reasons, are within the control of employees and hence beyond the scope of the company's or upper management's decision.

The initial and exploratory findings of the study showed that males dominate the middle management of the IHC's in Jordan. Eighty-four (84) per cent of the respondents were male and 16 per cent were female. This is consistent with findings of the study of the German Federal Institute for Vocational Training, which revealed that men appear to have a significantly higher proportion of opportunities for training and working abroad than women, with 65 per cent compared to 35 per cent (Study highlights benefits of foreign placements for young trainees, 2003).

Study Limitations, Strengths and Future Research Directions

This investigation into the determinants of IHCs' decision to invest in OCT, although limited to the perspective of one group - middle managers -, offers a major contribution to the existing stream of research in the hotel industry literature. However, given that the respondents in this research work were limited to middle managers, future research is needed to approach multilateral perspectives in other managerial levels, including junior managers and upper management, in order to reveal any bias in the perceptions reported by the middle manager group of survey respondents.

The four core constructs that informed the present study were attitudes toward OCT, benefits and usefulness of OCT, barriers to OCT and decision of IHCs to invest in OCT. Related constructs including ‘competition' and ‘prestige or stature' were not included. An investigation of the interaction of other such relevant core constructs with organisations' decisions to invest in OCT would be another possible area for future research.

Involving a quantitative measurement of the constructs of study, has added scientific flavour to the research work which will help both research experts and business managers to draw valuable conclusions from this work.

While the current study looked only at respondents from Jordan's IHCs, the study may be replicated in the future in local hotels of small and medium size, which would also provide a more comprehensive picture of the country's hotel market. In Jordan, such research is of great importance due to the current dearth of studies investigating tourism and particularly hotels.

One future research work direction that would surely add value both to the literature and to the world of business practitioners would be to explore the cost benefit of OCT, to provide top managers with needed information when facing the decision of whether to invest in training activities. This study could extend even further to investigate whether there is a direct link between training, particularly OCT, and hotel business profitability.

This study represents an original contribution to the field by illuminating the neglected area of OCT in the Jordanian hotel industry. The insights of middle managers explored through this research have the potential to contribute significantly to the enhancement of scholarship and practices relating to OCT for middle managers in IHCs.

7. Conclusion

This research study substantiates the notion that attitudes toward OCT and benefits and usefulness have direct positive effects on the decision of IHCs in Jordan to invest in OCT for middle managers, supporting the proposed framework. It bears noting that the effect of barriers on IHCs' decisions to invest in OCT was found to be indirect, mediated by attitudes. Barriers impacted attitudes toward OCT, and these in turn impacted the decision to invest. Contrary to expectations, the survey results also revealed that the benefits and usefulness of OCT did not impact top management attitudes, according to respondents.

Despite the narrow focus of the research (Jordan's IHCs) which may limit the applicability of the results, the current study is the only recent research dealing specifically with middle managers' training opportunities abroad. Nevertheless, by suggesting an original model for investigating company's decisions to invest in OCT, this study significantly enriches and deepens the current understanding of middle management training. As such, hotel business owners, middle managers and policy makers stand to benefit from the results of this study because it reveals the barriers, benefits, and selection criteria associated with OCT.

Its implications may also extend beyond IHCs, helping to cast light on training and human resource management practices throughout Jordan's considerable hospitality and tourism sector. Further research in other countries and in other types of lodging establishments could replicate the study and verify the findings.

REFERENCES

Aktaş, A., Aksu, A. A., Ehtíyar, R. & Cengíz, A. (2001). Audit of manpower research in the hospitality sector: an example from the Antalya region of Turkey. Managerial Auditing Journal, 16(9), 530-535. [ Links ]

Al-Hammad, F. (2006) National Difference in European Tourists' Responses to World Heritage as a Tourist Attraction. Unpublished Master thesis. Coventry University. [ Links ]

Analoui, F. (1999). Eight parameters of managerial effectiveness: A study of senior managers in Ghana. Journal of Management Development, 18(4), 362-390. [ Links ]

Banerjee, S. (2016.) Career development is highly dependent on professional knowledge and skill development through training programme in tourism sector. International Journal of Research and Engineering, 3(5), 30-31. [ Links ]

Baron, R. & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182. [ Links ]

Barrows, C. W. (2000). An exploratory study of food and beverage training in private clubs. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12(3), 190-197. [ Links ]

Baum, T., Amoah, V. & Spivack, S. (1997). Policy dimensions of human resource management in the tourism and hospitality industries. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 9(5), 221-229. [ Links ]

Boella, M. J. & Goss-Turner, S. (2005). Human resource management in the hospitality industry: an introductory guide. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

Burma, Z.A. (2014). Human Resource Management and Its Importance for Today's Organizations. International Journal of Education and Social Science, 1 (2), 85-94. [ Links ]

Central Bank of Jordan (2011). Annual Report. Amman: Ministry of Finance. [ Links ]

Conrady, R., and Buck, M (2008) Trends and issues in global tourism. Springer: London.

Costen, W. M. & Salazar, J. (2011). The Impact of Training and Development on Employee Job Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Intent to Stay in the Lodging Industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 10(3), 273-284. [ Links ]

Chand, M. (2016). Building and Educating Tomorrow's Manpower for Tourism and Hospitality Industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems, 9(1), 53-57. [ Links ]

Creelman, J. (1995). Pay and performance drive human resource agendas. Management Development Review, 8(3), 6-9. [ Links ]

Davidson, M. C. G. (2000) Organisational climate and its influence upon performance: A study of Australian hotels in South East Queensland. Unpublished Master thesis. Griffith University. [ Links ]

Denham, N., Ackers, P. & Travers, C. (1997). Doing yourself out of a job? How middle managers cope with empowerment? Employee Relations, 19(2), 147-159. [ Links ]

Farrell, D. (2005). What's the ROI of Training Programs? Lodging Hospitality, 61(7), 46-46. [ Links ]

Galagan, P. (1983). Training the American Way. Training & Development Journal, 37(10), 4-4. [ Links ]

Garavan, T. N., Heraty, N. & Barnicle, B. (1999). Human resource development literature: current issues, priorities and dilemmas. Journal of European Industrial Training, 23(4), 169-179. [ Links ]

Garavan, T. N. (1997). Training, development, education and learning: different or the same?. Journal of European Industrial Training, 21(2), 39-50. [ Links ]

German Federal Institute for Vocational Training (2003). Study highlights benefits of foreign placements for young trainees. Journal of European Industrial Training, 27(9). Doi.org/10.1108/jeit.2003.00327iab.007 [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., and Black, W. C. (1998) Multivariate Data Analysis. 5th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall International.

Hair, J., Black, B., Babin, B., Anderson, R., and Tathan, R. (2006) Multivariate data analysis. 6th ed. New York: Prentice Hall.

Harris, K. J. (1995). Training technology in the hospitality industry: a matter of effectiveness and efficiency. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 7(6), 24-29. [ Links ]

Harzing, A.W.K. (1997) "Response rates in international mail surveys: results of a 22 country study." International Business Review 6 (6) 641-665. [ Links ]

Huyton, J. R. & Ingold, A. (1999). A commentary by Chinese hotel workers on the value of vocational education. Journal of European Industrial Training, 23(1), 16-24. [ Links ]

Judd, C. M. & Kenny, D. A. (1981). Process analysis: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review, 5(5), 602-619. [ Links ]

Kim, J., Erdem, M., Byun, J. & Jeong, H. (2011). Training soft skills via e-learning: international chain hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 23(6-7), 739-763. [ Links ]

Kline, S. & Kimberly, H. (2008). ROI is MIA: why are hoteliers failing to demand the ROI of training? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(1), 45-59. [ Links ]

Kuruüzüm, A., Anafarta N. & Irmak, S. (2008). Predictors of burnout among middle managers in the Turkish hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(2), 186-198. [ Links ]

Ladkin, A. & Juwaheer, T. D. (2000). The career paths of hotel general managers in Mauritius. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12(2), 119-125. [ Links ]

Littrell, R. F. (2002). Desirable leadership behaviours of multi-cultural managers in China. The Journal of Management Development, 21(1), 5-74. [ Links ]

Madera, J.M., Madera, J.M., Dawson, M., Dawson, M., Guchait, P., Guchait, P., Belarmino, A.M. and Belarmino, A.M. (2017). Strategic human resources management research in hospitality and tourism: A review of current literature and suggestions for the future. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 48-67.

Magnini, V. P. & Ford, J. B. (2004). Service failure recovery in China. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 16(5), 279-286. [ Links ]

Marchington, M. and Wilkinson, A. (2002) People Management and Development. London: CIPD.

Marsh, H. W., Balla, J. R. & Hau, K. (1996). An evaluation of incremental fit indices: A clarification of mathematical and empirical properties. In: G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Ed.), Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques (pp. 315-353). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Marsh, H.W., Balla, J. R. & McDonald, R. P. (1982). Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103, 391-410.

McCarthy, Pat. (1990) "The Art of Training Abroad." Training & Development Journal 44, (11) 13-18. [ Links ]

Mohsin, A. (2007) "Assessing lodging service down under: a case of Hamilton, New Zealand." International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 19, (4) 296-308. [ Links ]

Nebel, E. C., Braunlich, C. G. & Zhang, Y. (1994). Career Paths in American Luxury Hotels: Hotel Food and Beverage Directors. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 6(6), 3-9. [ Links ]

Phillips, J.J. & Phillips, P.P. (2016) NEW Handbook of Training Evaluation and Measurement Methods. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Pine, R. & Qi, P. (2004). Barriers to hotel chain development in China. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 16(1), 37-44. [ Links ]

Ramos, V., Rey-Maquieira, J. & Tugores, M. (2004). The role of training in changing an economy specialising in tourism. International Journal of Manpower, 25(1), 55-72. [ Links ]

Read, C. W. & Kleiner, B. H. (1996). Which training methods are effective? Management Development Review, 9(2), 24-29. [ Links ]

Rouleau, L. & Balogun, J. (2011). Middle Managers, Strategic Sensemaking, and Discursive Competence. Journal of Management Studies, 48(5), 953-983. [ Links ]

Rowley, G. & Purcell, K. (2001). As cooks go, she went: is labor churn inevitable? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 20(2), 163-185. [ Links ]

Taylor, M. S. & Berger, F. (2000). Hotel Managers' Executive Education in Japan. The Cornel Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 41(4), 84-93. [ Links ]

Terterov, M. (2004). Doing Business with Kazakhstan. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

The Jordanian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (2016). Tourism Statistical Newsletter 2008, 7(4). Retrieved December 10, 2012, from http://www.mota.gov.jo/contents/Tourism_Statistical_Newsletter_2016.aspx [ Links ]

Timo, N. & Davidson, M. (2005). A survey of employee relations practices and demographics of MNC chain and domestic luxury hotels in Australia. Employee Relations, 27(2), 175-192. [ Links ]

Tsang, E. W. K. (1994). Human Resource Management Problems in Sino-foreign Joint Ventures. International Journal of Manpower, 15(9-10), 4-21. [ Links ]

Wang, Y. (2011). An Evaluation Tool for Strategic training and Development: Application in Chinese High Star-Rated Hotels. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 11(3), 304-319. [ Links ]

Received: 13.08.2016

Revisions required: 02.02.2017

Accepted: 25.03.2017