Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.3 Faro set. 2017

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Study of female entrepreneurship: an empirical evidence in the Municipality of León in Nicaragua

Estudio del emprendimiento en mujeres: evidencia empírica en el municipio de León en Nicaragua

*Justa Pastora Amador-Ruiz, ** Antonio Juan Briones-Peñalver

*Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua (UNAN), Edificio Central, Contiguo a la Iglesia La Merced, León, Nicaragua, justaamador4@gmail.com

**Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena (UPCT), Plaza Cronista Isidoro Valverde, 30202 Cartagena, Spain, and Research Centre for Spatial and Organizational Dynamics (CIEO), aj.briones@upct.es

ABSTRACT

Women's entrepreneurship is one of the main challenges in economic growth. In this sense, within the context of creating new companies, it can be considered as one of the main mechanisms that contributes to achieve the desired wellbeing in society. Women's entrepreneurship reduces unemployment, increases innovation, improves competitiveness and favors economic growth significantly. This article aims to analyze the influence of the socioeconomic and psychosocial factors involved in female entrepreneurship. For this purpose, we used a sample of 101 women entrepreneurs in the municipality of León, Nicaragua. We applied Factor Analysis and Regression Analysis, in order to find out the relationship between the considered factors. Some results indicate that all variables considered have a significant influence on the probability of entrepreneurship. The capacity of entrepreneurial women increases when they have skills, knowledge and an early contact in the business world.

Keywords: Female entrepreneurship, socio-demographic and psychosocial factors.

RESUMEN

El espíritu empresarial de las mujeres es uno de los principales desafíos del crecimiento económico. En este sentido, en el contexto de la creación de nuevas empresas, puede considerarse como uno de los principales mecanismos que contribuyen a lograr el bienestar deseado en la sociedad. El espíritu empresarial de las mujeres reduce el desempleo, aumenta la innovación, mejora la competitividad y favorece significativamente el crecimiento económico. Este artículo tiene como objetivo analizar la influencia de los factores socioeconómicos y psicosociales involucrados en el emprendimiento femenino. Para ello, se utilizó una muestra de 101 mujeres emprendedoras en el municipio de León, Nicaragua. Se aplicó análisis Factorial y de Regresión, con el fin de conocer la relación entre los factores considerados. Algunos resultados indican que todas las variables tienen una influencia significativa en la probabilidad de emprendimiento. La capacidad de las mujeres emprendedoras aumenta cuando tienen habilidades, conocimientos y un contacto temprano con el mundo de los negocios.

Palabras clave: Mujer,emprendimiento, factores socioeconómicos y psicosociales.

1. Introduction and objectives

In recent years, there has been an increase of women participation in entrepreneurship within the business environment. A major challenge for any country is to be able to take the entrepreneurship to a higher development stage (Amorós, Guerra, Pizarro, & Poblete, 2006), this needs to be done in order to consolidate the activities, which imply a greater impact in terms of employment, greater possibilities to grow in innovation and transformation that contribute to greater economic growth, competitiveness, quality and increase in the scope of the enterprise (Acs & Amorós, 2008).

Undoubtedly, in Nicaragua, as in most developing countries, women entrepreneurs have undergone major changes in the last decades, such as their widespread incorporation in the workplace, the improvement in their education level and their participation in the different social and political fields.

In this context, the diversity of women entrepreneurs in the municipality of León, Nicaragua, is characterized mostly by informal enterprises. This situation forces women to explore new patterns of growth and economic development within their family nucleus and their communities, taking into account their regional differences. That is to say how cultural influences, ways of being and thinking as defined in the different regions of the country (at a general level and particularly in the municipality of León) shape different ways of understanding women entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial development.

Another aspect worth mentioning is the fact that women entrepreneurs lack the necessary knowledge to develop their businesses. For this reason, when they are affected by difficulties they face in the market, such as globalization challenges, the technological revolution, and localization; overcoming these challenges will allow them to achieve sustainable competitive advantages in order to surpass social inequality.

Governments and international economic organizations have promoted policies and programs aimed at encouraging initiatives led by women in business. Hence, the incentives provided often serve the purpose of recognizing entrepreneurial women as an important social phenomenon. In this sense, in the context of creating new companies, women entrepreneurship, can be considered as one of the main mechanisms that contributes to achieve the desired welfare for society in an important way (Carter & Shaw, 2006).

This study has a two-fold purpose. Firstly, to conduct a literature review of the different factors that explain the role of entrepreneurship to increase the dynamism in the economy from the women's point of view. Secondly, to analyze the attitudes toward entrepreneurship in the municipality of León and, to determine if these variables are encouraging the economic strengthening of the city and consolidating its investment initiative. Thus, the scientific interest of the present study is aimed at helping design more effective policies to promote entrepreneurship in cities and recommending ways of fostering favorable women entrepreneurs' attitudes and initiatives.

2. Literature review and conceptual model

During the last decades the role played by the entrepreneurial woman, has undergone a great transformation process in relation to the woman's social position. The magnitude of this change is reflected in significant areas including a series of practices related to learning, whether formal or informal. Such practices are adopted on an ongoing basis with the aim of improving knowledge, skills and competence, key elements in stimulating the development of entrepreneurial activity to generate wealth and employment (Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004).

In order to understand the evolution and development of economy it is necessary to review the contributions that have been made in recent years regarding the concept of the entrepreneur. Nowadays, the focus of researchers is on the so-called entrepreneur or Schumpeterian entrepreneur, for his contribution to economic growth, both in social terms of employment generation and in social welfare (Rodríguez & Jiménez, 2005; Schumpeter, 1934), there is a broad spectrum of connotations in the field from different perspectives: economy, sociology and psychology. The creation of a sociological climate, for example, includes perceptions of what it is commonly understood or known as such, that it to say a socio-cultural environment that values and rewards entrepreneurship (Rodríguez, 1999). For instance, the presence of a woman`s character, who constantly assumes the risk of success or failure in her daily life. This character gives her the ability to create innovative enterprises, without forgetting risk acceptance and stimulation of competition.

In the literature on business dynamics, there have been many studies that attempt to explain the approach associated with entrepreneurship to envision new business opportunities (Álvarez, Noguera, & Urbano, 2012), and the importance of knowledge to explain what knowledge is and how the success of female entrepreneurship is determined (Chen, Greene, & Crick, 1998). Based on this approach, entrepreneurship requires some personal variables that describe the particular perceptions of each individual, and how these have a significant impact on the competences and abilities to find different alternatives for solution and achievement of objectives (Arenius & Minniti, 2005), specifically, from a very general perspective, there is some consensus (in both developing and developed countries) that the need to seek greater compatibility between work and family is a predominant factor in women's entrepreneurial dynamics (Castiblanco, 2016).

This influence is also shown in the field of entrepreneurship highlighting the determining factors in the understanding of individual behavior differences (Brandstätter, 2011), as reflection of individual actions. Success depends on a set of conditions such as culture, education, information, available technology and social norms (Acs & Amorós, 2008), as well as other individual variables related to personality and ability (Wennekers, Stel, Thurik, & Reynolds, 2005). From the psychological approach, entrepreneurship depends largely on the disposition and willingness of individuals to initiate an independent business, the skills of women involved and the efforts for the necessary successful implementation (>Kantis, Angelelli, & Moori, 2004).

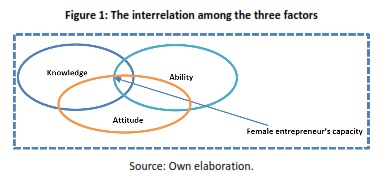

Among the individual variables, we find, in turn, the convergence of three basic elements of entrepreneurship (figure 1), those objective variables, knowledge, skills to know how to apply them, (aptitude) that can be acquired and developed and with another series of cognitive variables that relate to the way in which the female entrepreneur processes the information that comes from the environment attitude (personal attributes) and the perception she has of existing opportunities, her own abilities, and the risks inherent in the business.

One of the explanatory factors that try to measure business intentions is the attitude of the individual towards the behavior of the company. That is to say, personal evaluation positive or negative contributes to the intention to create a company is greater this behavior (Linan, 2008).

The capacity to pursue entrepreneurship is a concept little used in the psychological literature (Bird & Wennberg, 2016), however, the impact of the leader's intentions on skills and competencies is made up of the skills and aptitudes, knowledge and qualities of entrepreneurial women and result from the development of skills acquired throughout their lives from learning and experience (Bird, 1988).

Creativity is usually defined as “the ability" inherent to human beings. As defined by entrepreneurship, through creativity women are able to extract new forms of creativity and establish new relationships. This link to knowledge can be labeled as the capacity to create business knowledge (Lee, Florida, & Acs, 2004).

In this sense, Schumpeter (1934) considers that within economies that operate in a constant state of imbalance, the motivations of the individual act as drivers of business conduct, lies in technological, political, social, regulatory and other types that offer a continuous supply of new information about different ways of using resources to improve wealth (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000).

According to Drucker (1985), creativity and innovation are the specific instruments of entrepreneurs representing the way in which entrepreneurs exploit change as a previously non-existent opportunity (Verheul & Thurik, 2001), creativity and innovation involve an individual's intention of creating something new, the ideas to develop products / services, abilities to find solutions to their needs, and desires to continue to learn (Carter & Ram, 2003).

The successful entrepreneur arises from a highly motivated person who believes he/she possesses skills, qualities and behavioral characteristics to perform his/her tasks, successfully (Amorós, 2011), important components associated with success are the initiative and optimism that usually emerge as a result of personal skills and creative and innovative abilities, which develop from the surrounding reality (Langowitz & Minniti, 2007).

The multifaceted and dynamic nature of entrepreneurial women has focused on different factors that explain their position in order to increase the dynamism in economy (De Bruin, Brush, & Welter, 2007), these factors can be distinguished. Firstly, the economic approach, aspects related to economic rationality (Álvarez & Urbano, 2013), roughly speaking it is argued that female entrepreneurship is due to their entrepreneurial capacity and is related to the performance of the company, sector or country (Anna, Chandler, Jansen, & Mero, 2000; Carter & Shaw, 2006), secondly, the psychological approach which states that the psychological traits are the determining factors of the entrepreneurial activity (Carter & Shaw, 2006). Finally, the sociological approach, which points out that the socio-cultural environment, conditions the decision to create a company (Alvarez, Urbano, & Amorós, 2012).

One of the entrepreneurship models to which more reference is made involves the entrepreneurial process, the entrepreneur's personality traits, and the environment in which the process is developed (Acs & Amorós, 2008, Alvarez, Urbano, & Amorós, 2012). Within the studies carried out, focused on the entrepreneur and her act of innovation, three main lines of research are recognized. These studies are based on the approaches that characterize female entrepreneurship, central object of this study:

2.1 Economic approach

Here we will consider among the demographic factors the variables age and education. From the point of view of the benefit to the entrepreneur (Veciana, 2007), indicates that this aspect has been object of study from its origins. The classic economic theories tend to incorporate aspects like "entrepreneur risk", innovation, and leadership. The entrepreneurial nature, from the economic point of view, implies a unique continuous process that combines both the individual's internal factors (such as personality, values, objectives, etc) with the external factors such as resources allocation, and decision-making, (society, the government, economy, etc.). This combination helps some specific people (the entrepreneurs) to visualize opportunities that will eventually become projects likely to implement (Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004).

In the previous literature reviewed, socioeconomic factors, specifically the age variable, is a predictor commonly used to establish causes of success, (Castiblanco, 2016; Holienka, Jančovičová, & Kovačičová, 2016), asserting that the probability of pursuing entrepreneurship increases as the age of the person increases (Langowitz & Minniti, 2007), family and personal responsibilities increase the perception of business risk, implying that the probability of starting a new business peaks, as age increases and the number of women interested in starting a business decreases (Arenius & Minniti, 2005), there is no empirical evidence showing that age influences differently at the time of pursuing entrepreneurship (Holienka et al., 2016)

Most research suggests that there should be a positive relationship in socio-demographic characteristics, since a society can benefit from women of all ages. In a business context, socio-demographic factors have been used in the characterization of entrepreneurial women (Castiblanco, 2016).

Based on these arguments, we propose the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. The probability that a woman intends to pursue entrepreneurship: age has an effect on the intention to pursue entrepreneurship.

2.2 Education

Research on female entrepreneurship considers the educational level as a major human capital indicator. Given its nature, female entrepreneurship necessarily requires the development of certain capacities (Verheul & Thurik, 2001), and implies different knowledge base and information (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), this difference, in turn, may explain that women with more training and experience are more likely to take advantage of their knowledge, contacts and capital saved (Bosma, Hessels, Schutjens, Van Praag, & Verheul, 2012), however, these same women are more reluctant to introduce innovations and technology into the market.

Carter & Shaw (2006) evidence this in their review. They find that there is a great variety of ways to classify women's achievement, which involves the level of education and work experience. Veciana (1989), in turn, indicates in his study that the entrepreneur's level of education is not decisive for the creation of companies. According to Bird & Wennberg (2016), the positive relationship between entrepreneurship and education, which has emerged in more developed countries, suggests that adopting a strategy would be a predominant factor in women's entrepreneurial dynamics (Arenius & Minniti, 2005).

On the other hand, the presence of women is almost a testimony in the construction of that activity where the skills required to establish a business are minimal and relatively easy to learn, focusing on trade and professional services (Pilková, Jančovičová, & Kovačičová, 2016).

Authors such as Angelelli & Llisterri (2003), Minniti & Naudé (2010), argue that structural problems in women's education also limit their access to technical training. This limitation may in turn affect their access to knowledge of new technologies, which can potentially benefit the development and growth of their enterprise. However, qualitative research carried out in Latin America show that most of the training courses offered are difficult to adapt to match women entrepreneurs' needs (Powers & Magnoni, 2010).

Hypothesis 2: Having an education exerts a positive effect on women who intend to pursue entrepreneurship

2.3 Psychological Approach

Among the factors, we will consider the variables related to perception of self-confidence (ability), family background, and knowledge of another entrepreneur. From a psychological perspective, some authors have attempted to understand the personality traits that define an entrepreneur and his/her decision-making processes, this approach implies a radical change from the economic approach, based on the methodological point of view (Veciana, 1999).

Empirical research that tries to determine the psychological characteristics in a regional or cultural scope evidences the existing differences between entrepreneurs and those who are not, and between those who succeed and those who do not, without exemption of uncertainty and risk and those who decide to develop their professional career (Veciana, 1999).

2.3.1 Abilities

According to Bandura and Walters (1977), the capacities and abilities arising from business practices largely explain their behavior and subjective character. This is based on the extent to which the entrepreneurial woman perceives the capacities she has herself, with the objective of achieving competitive advantage (Krueger, Reilly, & Carsrud, 2000).

(Anna et al., 2000), consider that the perceived results of a woman's self-efficacy can improve when integrating into the local market, through a favorable environment in which she integrates that can be useful to differentiate her capacities. This new dimension implies for women the following capacities (1). Perceived capacity to recognize an opportunity, (2). Ability to generate ideas and (3). Ability to recognize, imagine and take advantage of the opportunity (this ability is referred to as competence). These abilities play an important role in the survival and growth of the company.

Hypothesis 3: The belief in having unique skills has a positive effect on women entrepreneurs

2.3.1.2 Family background

Family background plays a determining role in learning when making a decision to create a company where different effective components develop: solidarity, skills, habits and attitudes that are part of this conception, especially in business management (Gibb, 1987). The influence of an individual from the part of parents and/or people with a degree of closeness and affection is explained by mechanisms of social learning theory, in many cases, more personal than operational support is required at the enterprise level (Noguera, Alvarez, Merigo, & Urbano, 2015).

In Latin America, evidence indicates that the educational system and family are not the most effective contexts for motivating and training entrepreneurs (Angelelli & Llisterri, 2003). Researchers have not yet considered relevant how the family can trigger events that stimulate recognition of entrepreneurial opportunities (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003), although it is recognized that family members contribute to the formation of important values, such as the ability to work hard (Angelelli & Llisterri, 2003)

Hypothesis 4: Having a family background in entrepreneurship matters has a positive effect on the establishment of a company

2.4 Sociological approach

Among the factors, we will consider the variables related to perception of self-confidence (ability), family background, and knowledge of another entrepreneur.

The first studies under this approach appeared in the early twentieth century, and more systematically in the 1960s (Veciana, 1999), from a perspective that includes sociological and cultural elements. This approach starts from a broader analysis, considering that within creation of new enterprises the characteristics are acquired in terms of: personal experiences (family origin, education, previous occupational experience, lifestyle, class structure, etc.) and the environment in which the new enterprise will be developed (facilitator environment, corporate culture).

2.4.1 Social Capital

A major number of businesses are aware that associativity might contribute as a way of spontaneous cooperation between small businesses. This constitutes a social capital in order to favor their economic growth and increase their competition.

In Latin America, Bid & Cepal (2010) analyzed in their empirical study the raise of women associations and how they play an important role in facilitating women's access to social capital. From literature to social capital, De Nieve and Briones (2009), distinguish three reasons that motivate the entrepreneurial activity: a) the economic, characterized by the exchange of resources or activities; b) the strategic, associated to the value produced in the networks, and, c). the social, based on the trust of the actors involved in the network.

On the other hand, the fact of understanding social capital as an entrepreneurial process(Aldrich, Zimmer, & Jones, 1986), might be a predicting variable in the probability of starting a business, as contact networks are important resources of knowledge and new ideas, as facilitators of female entrepreneurship, self-employed women examine their human and social capital (Langowitz & Minniti, 2007), this implies the existence of increased contacts to develop cooperation agreements in accordance with the discovery of opportunities and may exert influence on the propensity to innovate and undertake entrepreneurial initiatives.

From another perspective, it has been pointed out that the usefulness of social contacts lies in information, as well as in networks as crucial elements to access financing, technology, commercial channels, as well as links with suppliers and investors (Aldrich et al., 1986), at the same time, there is influence on women's self-confidence levels and, therefore, in their intention to be entrepreneur.

Empirical evidence indicates that women predominantly implement informal social networks (personal and close ties), both of which may be indicative of the existence of a network of entrepreneurial contacts that provides them with relevant social capital for the formation of their intention to pursue entrepreneurship. In their study, Ruiz & Cordura (2012), indicate that one of the factors that hinder women's initiative, are social networks. As an example, microenterprises, such as street vendors, often struggle to earn enough money, so that social networking and capital building are particularly important in developing new business contacts.

Hypothesis 5: Having agreements or alliances with companies of the industry, cause a positive effect on the interest to develop technology and innovation in the establishment of a company. Finally, it should be emphasized that the theoretical and empirical evidence show motivations that drive

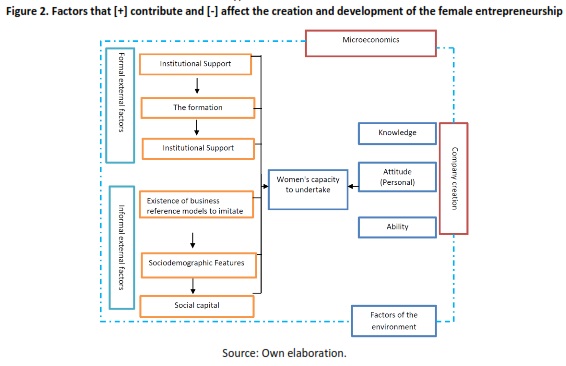

Finally, it should be emphasized that the theoretical and empirical evidence show certain tendencies about the type of entrepreneurship that women choose, the attitudes and motivations that drive them to pursue entrepreneurship or not, and their level of education. These aspects are framed to some extent within the factors identified in Figure 2.

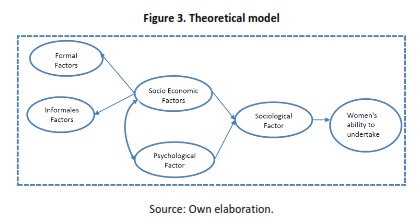

The hypotheses are summarized in Figure 3.

3. Methodology

3.1 Variables and Measurement

In order to measure our dependent variable, we focus on one item of the questionnaire applied through a personal survey in a field study. As support document, we used a self-administered questionnaire directed to businesses' owners. Do you consider that lack of knowledge, lack of training, experience, and family responsibilities impose obstacles? It is a dichotomous variable, which takes the value 1 for an affirmative answer and value 2 for a negative answer.

Regarding socio-demographic factors, to measure age we used a continuous variable that takes ages 25-34 in value 1, ages 35-44 in value 2 and ages 45-82 in value 3. For education, women with primary education are included in value 1, women who achieved secondary school level are included in value 2, and those who had higher education (bachelor degrees or graduate levels) are included in value 0.

Cognitive variables were measured through a Likert-type variable (values 1 to 7).

Regarding relational variables, they were also measured through a Likert-type variable (values 1 to 7).

4. Empirical Study

4.1 Sample

To test our model, the study population consists of entrepreneur women from the municipality of León, Nicaragua, with a sample of 101 women, with a confidence level of 95% and a standard error of 5%.

4.2 Analysis and Results

Before carrying out the relevant statistical analysis, it is necessary to ensure that adequate tools are being used to measure the concepts that we intend to measure. Therefore, we corroborated the reliability and validity of the scales used to measure each of the variables. To measure reliability, Cronbach's alpha was used. In order to increase the values of the alpha coefficient, the criterion of item-total correlation was followed to determine if an item should be eliminated (Wang, 2003). The validity of each scale was checked by factorial analysis. With this analysis we tried to verify if each scale was measuring a single concept. For all variables, Cronbach's alpha values were higher than the minimum recommended. All the items showed an item-total correlation higher than 0.3, so all the initial items were kept. Before the factorial analysis, the suitability was determined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin or KMO statistic and the Barlett sphericity contrast. Satisfactory values were obtained for all variables, both for the KMO index and for the Bartlett test, so that the various factor analysis were carried out.

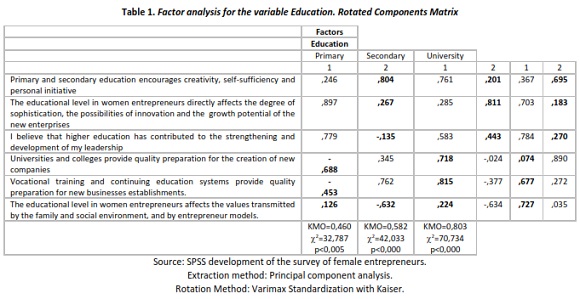

In the case of the Education variable, using factorial analyzes, the results indicate that there are significant differences in the level of education; although it is important to note the differences in the level of education of primary women (c2=32,787 p <0.005) ensures that the educational level directly affects the degree of sophistication. In those with secondary education (c2 = 42,033 p <0,000), it affects the possibilities of innovation and the growth potential of the new enterprises. In the case of women with a higher formation (c2= 70,734 p <0,000), their education has contributed to the strengthening and development of their leadership, which may be a disadvantage in relation to women who are not trained to pursue entrepreneurship in certain sectors (Brush, 1992). The first part of Table 1 clearly shows the predominance of female education related to their educational level, a fact that agrees with the arguments presented by the literature on this subject.

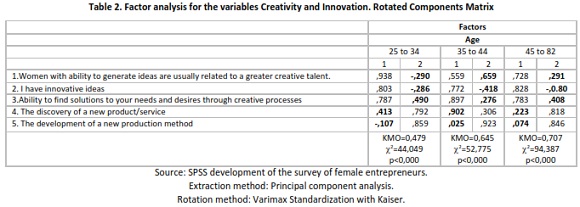

In terms of socio-economic factors, the average age is 49 years. Table 2 shows the factorial analysis of the variables. We deduce that all the proposed variables that make Model 1 have a significant relation with the probability that the woman with personal abilities and creative and innovative capacities is a potential entrepreneur.

Thus, as age (45 to 82) increases, it exerts a negative effect and this probability decreases (c2 = 94.387 p <0.000). The analysis show that, when the age of the entrepreneurial woman is in the group (25 to 34), (c2 = 44.049 p <0.000) within the creativity and innovation scale; this is a predictor that prevails in the first five items with greater intensity on initiative taking to generate ideas related with the skill through creative processes. For the entrepreneurial women in group (35 to 44), (c2 = 52,775 p <0,000), the probability of implementing their skills prevails. It seems that there is an age range acting an inhibiting barrier when women start a business. However, for entrepreneurial women with few creative abilities this barrier occurs at older ages, while entrepreneurs with creative abilities would have a greater "timeframe" to carry out their initiatives. These results confirm partly the proposed hypothesis (Castiblanco, 2016; Holienka et al., 2016), that women entrepreneurs with a high level of education frequently require to start their entrepreneurial activities later.

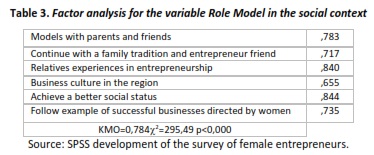

In order to determine the minimum number of factors, a confirmatory factorial analysis is carried out in order to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement scales used in this investigation Table 3 presents the Beta Standardized coefficients that constitute a measure of the contribution of each variable to the predictive model. The higher values indicate that any change in the predictor variable may have a significant effect on the criterion variable; since statistics take values very close to 0.8, therefore none of them will be excluded.

The significance of the Barlett test (c2= 295.49 p <0.000) and the KMO (.784) showed an adequate correlation between the items and a good sample adequacy respectively. An initial estimation of the model indicates that two elements explain the experience scales of family in entrepreneurship and experience of family in entrepreneurship. They showed significant values in their influential role on the variable role model in the social context, which shows that women entrepreneurs do not come from business households and the vast majority, do not have an early contact in the business world. This characteristic allows us to verify statements (Gibb, 1987), that family history plays a determining role in learning when making a decision to start a business and in many cases entrepreneurs require more personal than operational support at the corporate level (Noguera et al., 2015). Consequently, the H3 hypothesis is also accepted.

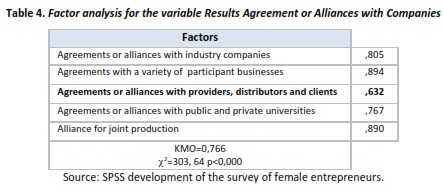

From the Factor Analysis model for the variable Results Agreement or Alliances with Companies (see table 4), referring to the informal factor of the contact networks, it is evident that the scales indicate a correct approach of the factorial structure, given that statistics take very close values.

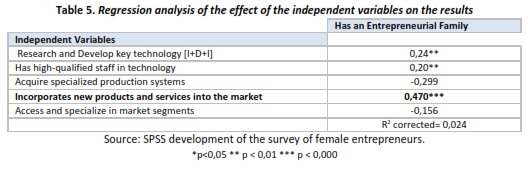

Therefore, none will be excluded. Subsequently, a relationship between the level of analysis and agreements with entrepreneurs was explored. The results indicate a significance of the Barlett test (c2 = 303, 64 p <0.000) and the KMO (0.766). An initial estimate of the model indicates that to pursue entrepreneurship it is necessary to be surrounded by a business ecosystem. In this case it negatively affects entrepreneurship in the municipality of León. The beta exponential indicates that there is a statistical association between the level of analysis and the social capital factor. In the case of the municipality of León, female entrepreneurs are observed to practice strategies with suppliers, distributors and customers. As a result, being surrounded by a business ecosystem is determined by the confidence of the actors who participate in the network and are likely to increase the effectiveness in their businesses. The presence of women in the municipality of León, Nicaragua, is almost a testimony in the construction of those activities where the skills required to establish a business are minimal and relatively easy to learn, concentrating on trade and professional services (Pilková et al., 2016). The results show that having entrepreneurial families, (both in innovation, as highly qualified personnel), acquiring a production system, incorporating new products in the market, and accessing and specializing in the market segment; are all factors the influence the independent variable in a positive way

Table 5 shows the results for logistic regression in order to predict the influence of entrepreneurial relatives as a control variable based on cognitive and socio-personal factors. It is observed that coefficient B differs significantly from 0; therefore, it is understood that it produces changes on the dependent variable indicating the inexistence of a relationship. Although no hypothesis was proposed, in the case of some authors who used this variable, we found out that having family entrepreneurs does exert an influence (Gibb, 1987; Veciana, 1989).

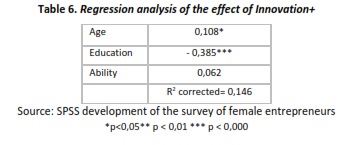

On the other hand, hypothesis 3 proposed that cooperation influences innovation positively. The relationship between the two variables was analyzed (see Table 6), showing that, in the case of Age, Education and Skill, they positively influence innovation. Consequently, hypothesis 3 is accepted. However, in the businesses of the municipality of León, only those cases, in which women have a higher education result in a greater innovation. Therefore, hypothesis 3 is partially accepted.

Finally, hypothesis 5 suggested that social capital, in relation to the informal factor, can foster cooperation. The analysis in Table 6 confirm that education positively influences cooperation with both direct and indirect agents. Therefore, hypothesis 5 is also accepted. No practice of social capital results in greater cooperation with competition. Therefore, hypothesis 5 can only be partially accepted.

5. Conclusions

The present study has analyzed with empirical evidence the different factors that explain the position of entrepreneurial women to increase their dynamism in the economy in the municipality of León, Nicaragua. We tried to prove the three-dimensional conception of the construct, based on the economic, psychological and sociological defended by (Álvarez & Urbano, 2013), this influence of the three-dimensional conception globally incorporates, aspects related to economic rationality and the action of entrepreneurial women in the light of change. Two basic premises support and guide the research conducted. Firstly, socio-economic variables try to test the possible influence of entrepreneurial women's ability (Anna et al., 2000; Wennekers et al., 2005), on psychological factors. Such factors determine the understanding of the processes (Alvarez, Urbano, & Amorós, 2012), that give rise to success in the implantation of the entrepreneurial woman's personality. Secondly, the socio-cultural environment can condition the decision to create a company (Alvarez et al., 2012). In this sense, the perceptions of entrepreneurial skills have a very significant effect on the three motivational constructs considered (aptitude, ability and training).

As has been shown by factor analysis, given the relationship among these three elements they are interrelated, so that some empower others maintaining a common goal: women's attitude towards business behavior and self-efficacy. Self-perceived entrepreneurial skills are closely linked to this variable. However, business skills are measured by a list of very specific skills. In contrast, positive or negative attitudes that contribute to the intention to pursue entrepreneurship have been measured as an added sense of capacity or control. Therefore, the perception that these skills are owned traits strengthens the link with knowledge, which can be labeled as the ability to create business knowledge.

This research provides a first radiograph of entrepreneur women, identifying the central peculiarities of women's entrepreneurial spirit in the municipality of León, Nicaragua and in its companies.

From the results obtained, the average age is 49 years. In the factorial analysis, the variable age presented a highly significant effect with negative coefficient β in older women. This relationship increases as soon as it is introduced in the model of Creativity and Innovation, which leads us to interpret how age acts as an inhibiting barrier when starting a business.

If we take into consideration, the influence that education has according to our results, a high level of education requires social self-evaluation of entrepreneurship and it has a positive effect on the perception of skills. This finding may also be important for business policy in general, and specifically for education.

The direct influence of values on the antecedents of relatives in the intention to pursue entrepreneurship indicates aspects linked to the influence of a closer environment. Such environment comprises models of parents of friends, and follows examples of successful companies, affective elements that are influential on the assessment of entrepreneurship. This shows that entrepreneur women do not come from business households and the vast majority do not have an early contact in the business world. This characteristic makes it possible to verify that, due to the need to seek greater personal and family compatibility, ranging from genetics to education. It is a predominant factor in the entrepreneurial dynamic and there is no significant effect on the Role Model assessment.

Regarding the informal factor of the contact networks, it is evident that the lack of affiliation to mentors linked to business success and the cultural aspect indicates that entrepreneur women from Leon tend to build businesses "imitating" business models where the required skills to establish themselves are minimal and relatively easy to learn, concentrating on trade and professional services. This proves the statements by (Pilková et al., 2016) therefore the development of skills such as opportunity, recognition, creativity, leadership, communication and innovation, are necessary for business success.

Finally, we believe that it should be analyzed the inclusion of specific contents in Education as well as the compatibility between work and family for the entrepreneurial spirit that explain the decline of its nature. The abilities of entrepreneur women are essential for understanding business processes. These contents would be a very important complement to visualize new business opportunities.

REFERENCES

Acs, Z. J. & Amorós, J. E. (2008). Entrepreneurship and competitiveness dynamics in Latin America. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 305-322. doi: 10.1007/s11187-008-9133-y [ Links ]

Aldrich, H. E. & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9026(03)00011-9 [ Links ]

Aldrich, H., Zimmer, C. & Jones, T. (1986). Small business still speaks with the same voice: a replication of ‘the voice of small business and the politics of survival'. The Sociological Review, 34(2), 335-356. [ Links ]

Álvarez, C., Noguera, M. & Urbano, D. (2012). Condicionantes del entorno y emprendimiento femenino: un estudio cuantitativo en España. Economía industrial(383), 43-52. [ Links ]

Álvarez, C., & Urbano, D. (2013). Diversidad cultural y emprendimiento. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 19(1). [ Links ]

Amorós, J. E. (2011). El proyecto Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): una aproximación desde el contexto latinoamericano. Academia. Revista latinoamericana de administración(46), 1-15. [ Links ]

Amorós, J. E., Guerra, M., Pizarro, O. & Poblete, C. (2006). Mujeres y actividad emprendedora en Chile. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. [ Links ]

Angelelli, P., & Llisterri, J. J. (2003). El BID y la promoción de la empresarialidad: lecciones aprendidas y recomendaciones para nuevos programas. Inter-American Development Bank. [ Links ]

Anna, A. L., Chandler, G. N., Jansen, E. & Mero, N. P. (2000). Women business owners in traditional and non-traditional industries. Journal of Business venturing, 15(3), 279-303. [ Links ]

Arenius, P. & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small business economics, 24(3), 233-247. [ Links ]

Audretsch, D. & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional studies, 38(8), 949-959. [ Links ]

BID & CEPAL (2010). "Cómo reducir las brechas de integración”, Nota de discusión de políticas, [ Links ] Tercera Reunión de Ministros de Hacienda de América y el Caribe, Lima, Perú, mayo.

Bird, B. J. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of management Review, 13(3), 442-453. [ Links ]

Bird, M. & Wennberg, K. (2016). Why family matters: The impact of family resources on immigrant entrepreneurs' exit from entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 687-704. [ Links ]

Bosma, N., Hessels, J., Schutjens, V., Van Praag, M. & Verheul, I. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 410-424. [ Links ]

Brandstätter, H. (2011). Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: A look at five meta-analyses. Personality and individual differences, 51(3), 222-230. [ Links ]

Brush, C. G. (1992). Research on women business owners: Past trends, a new perspective and future directions. Small Business: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management, 1038-1070.

Carter, S., & Ram, M. (2003). Reassessing portfolio entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 21. doi: 10.1023/a:1026115121083 [ Links ]

Carter, S. & Shaw, E. (2006). Women's business ownership: Recent research and policy developments. Report to the Small Business Service. Retrieved April 20, 2017 from http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/8962/1/SBS_2006_Report_for_BIS.pdf [ Links ]

Castiblanco, M. S. E. (2016). Female entrepreneurship in a forced displacement situation: The case of Usme in Bogota. Suma de Negocios, 7(15), 61-72. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sumneg.2016.02.004 [ Links ]

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G. & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295-316. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3 [ Links ]

De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G. & Welter, F. (2007). Advancing a framework for coherent research on women's entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 31(3), 323-339. [ Links ]

De Nieve, N. C. & Briones, P. A. J. (2009). Las empresas de economía social y su relación con las instituciones: colaboración con la universidad en asuntos medioambientales. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa(65), 85-111. [ Links ]

Gibb, A. A. (1987). Enterprise culture—its meaning and implications for education and training. Journal of European Industrial Training, 11(2), 2-38. [ Links ]

Holienka, M., Jančovičová, Z. & Kovačičová, Z. (2016). Drivers of women entrepreneurship in visegrad countries: GEM evidence. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 220, 124-133. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.476 [ Links ]

Kantis, H., Angelelli, P. & Moori, V. (2004). Desarrollo emprendedor. América Latina y la experiencia internacional, 35-198. [ Links ]

Krueger, N., Reilly, M. & Carsrud, A. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9026(98)00033-0 [ Links ]

Langowitz, N. & Minniti, M. (2007). The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 31(3), 341-364. [ Links ]

Lee, S. Y., Florida, R. & Acs, Z. (2004). Creativity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of new firm formation. Regional studies, 38(8), 879-891. [ Links ]

Linan, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: how do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 257-272. [ Links ]

Minniti, M. & Naudé, W. (2010). What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries? The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 277-293. [ Links ]

Noguera, M., Alvarez, C., Merigo, J. M. & Urbano, D. (2015). Determinants of female entrepreneurship in Spain: an institutional approach. Springer Science+Business Media New York, 21, 341–355. [ Links ]

Pilková, A., Jančovičová, Z. & Kovačičová, Z. (2016). Inclusive Entrepreneurship in Visegrad4 Countries. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 220, 312-320. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.504 [ Links ]

Powers, J. & Magnoni, B. (2010). Dueña de tu propia empresa: Identificación, análisis y superación de las limitaciones a las pequeñas empresas de las mujeres en América Latina y el Caribe. Washington, DC: Fondo Multilateral de Inversiones, BID. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, A. (1999). La lógica originaria del emprendedor [documento de investigación No. 382]. Barcelona, Spain: IESE. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, C. & Jiménez, M. (2005). Emprenderismo, acción gubernamental y academia. Revisión de la literatura. Innovar, 15(26), 73-89. [ Links ]

Ruiz, N. J. & Cordura, M. A. (2012). Mujer y desafío emprendedor en España. Características y determinantes. Economía industrial, 383, 13-22. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle (Vol. 55): Transaction publishers. [ Links ]

Shane, S. & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25. [ Links ]

Veciana, J. M. (1989). Características del empresario en España. Papeles de Economía Española, 39. [ Links ]

Veciana, J. M. (1999). Creación de empresas como programa de investigación científica. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la empresa, 8(3), 11-36. [ Links ]

Veciana, J. M. (2007). Entrepreneurship as a scientific research programme Entrepreneurship. Berlin: Springer. [ Links ]

Verheul, I. & Thurik, R. (2001). Start-up capital:" does gender matter?". Small business economics, 16(4), 329-346. [ Links ]

Wang, Y. (2003). Assessment of learner satisfaction with asynchronous electronic learning systems. Information & Management, 41(1), 75-86. [ Links ]

Wennekers, S., Stel, A. V., Thurik, R. & Reynolds, P. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24. doi: 10.1007/s11187-005-1994-8

Received: 20 December 2016

Revisions required: 13 March 2017

Accepted: 05 May 2017

Acknowledgements

This paper is financed by, National Council of Universities- Nicaragua, National Autonomous University of Nicaragua, León/ Technological University of Cartagena (UCPT)/2017.