Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.1 Faro mar. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14109

MANAGEMENT: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Enhancing consumer attitudes toward a website as a contributing factor in business success

La actitud hacia el sitio web como factor clave del éxito empresarial

Juan Miguel Alcántara-Pilar*, Francisco Javier Blanco-Encomienda**, Mª Eugenia Rodríguez-López***, Salvador Del Barrio-García****

* University of Granada, Department of Marketing and Market Research, Faculty of Education, Economy and Technology, c\Cortadura del Valle, s.n. 51001 - Ceuta, Spain, jmap@ugr.es

** University of Granada, Department of Quantitative Methods for Economics and Business, Faculty of Education, Economy and Technology, c\Cortadura del Valle, s.n. 51001 - Ceuta, Spain, jble@ugr.es

*** University of Granada, Department of Marketing and Market Research, Faculty of Education, Economy and Technology, c\Cortadura del Valle, s.n. 51001 - Ceuta, Spain, eugeniarodriguez@ugr.es

**** University of Granada, Marketing and Market Research Department, Business and Economics Faculty, 18071 Granada, Spain, dbarrio@ugr.es

ABSTRACT

This paper examines how consumers develop their attitude toward a destination website and are influenced by its usability, perceived risk and perceived usefulness – all of which can enhance their purchase intention. To create an authentic browsing scenario for the study, a website was specially designed for a fictitious tourist destination. Participants were invited to browse the site freely while carrying out the task assigned to them. This approach contributed added value to the research by simulating the real behavior of consumers who are faced with a range of options when selecting their purchase. The findings confirm that perceived usability and usefulness exert a positive influence on attitude toward the website, while the effect of the perceived risk is negative. The key implication is that if tourism business managers can better understand how attitude toward a website is developed this will enable them to market their products and services more effectively.

Keywords: Tourist destination, website, attitude, consumer, purchase intention.

RESUMEN

Este estudio examina cómo la actitud de los consumidores hacia el sitio web de un destino turístico está influenciada por su facilidad de uso, por el riesgo percibido y por la utilidad percibida, pudiendo todo ello aumentar su intención de compra. Con el fin de crear un auténtico escenario en el que navegar, se creó un sitio web diseñado específicamente para un destino turístico ficticio. Los participantes fueron invitados a navegar por el sitio web libremente mientras realizaban ciertas tareas que se les habían asignado. El valor añadido de esta investigación radica en simular el comportamiento real de los consumidores, los cuales se enfrentan a una amplia gama de opciones a la hora de seleccionar su compra. Los resultados confirman que la facilidad de uso y la utilidad percibidas ejercen una influencia positiva sobre la actitud hacia el sitio web, mientras que el efecto del riesgo percibido es negativo. La implicación más importante de este trabajo es que si los gerentes de las empresas de turismo conocen mejor los aspectos que influyen en la actitud hacia un sitio web, esto les permitirá comercializar sus productos y servicios de manera más eficaz.

Palabras clave: Destino turístico, sitio web, actitud, consumidor, intención de compra

1. Introduction

The Internet, as a medium registering over 3,366 million users world-wide by the end of 2015 (Internet World Stats, 2016), has become one of the main sources of information for identifying products and services, and has transformed the purchasing environment. Websites worldwide serve as a global competitive tool for promoting products and services, attracting potential consumers and enhancing users’ purchase intention. But it has been found that consumers will browse a website only if they perceive it to be useful (Castañeda, Muñoz- Leiva & Luque, 2007), usable (Green & Pearson, 2011; Mazaheri, Richard & Laroche, 2011) and secure (Chang, Cheung & Tang, 2013; Green & Pearson, 2011; Mohseni, Jayashree, Rezaei, Kasim, & Okumus, 2016).

The present research therefore examines the influence of perceived risk online and perceived website usability and usefulness on the attitude toward the website generated by the user. To fulfill this objective a promotional website was created, representing a fictitious tourist destination. The participants selected for the study were British Internet users.

In this paper we will first examine the different influences on the customer’s attitude toward the website, highlighting some of the existing literature on this question and presenting the hypotheses we developed for our research. We then describe how we conducted the research and the results we achieved. Finally, we take a look at the conclusions from our study and its business implications.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 Website perceived usability and attitude toward the site

Usability refers to the speed and ease with which users are able to carry out their tasks via a given website (ISO, 1998). A website with good usability is one that is well organized, shows and

explains the products and services clearly and concisely, makes any registration process as simple as possible, downloads quickly and fosters positive experiences for the user (Nielsen & Coyne, 2001). Given the nature of this variable, observation alone cannot provide a complete picture: user opinion is the only means of measuring it comprehensively (Bevan, 2009).

Some authors have approached usability from a hedonic perspective (Brave & Nass, 2008), examining elements such as font type, use of color, design (Sonderegger & Sauer, 2010), animation, sections or structure of the interface, how ideas are organized or the emphasis of key messages (Schmidt, Liu & Sridharan, 2009), all of which are linked to attitudes and emotions (Thüring & Mahlke, 2007). Meanwhile, other authors have studied observable elements, taking a utilitarian or functional approach. Such elements include the website’s effectiveness, efficiency and capacity to generate satisfaction for the user in their pursuit of specific goals (Seffah & Metzker, 2004), ease of learning or attitude in terms of acceptable levels of human cost such as feeling of tiredness, upset or frustration and personal effort (Shackel, 1991). Authors such as Cappel and Huang (2007) add a further measurable category of usability, in the form of likelihood of error. Still others also consider speed of access to a website (and display rate within it), navigation layout and sequencing, content (in terms of quantity and variety of information, personalization and interactivity) and capacity to respond to the user (via feedback and FAQ functions, for instance) (Palmer, 2002).

Usability has been proved empirically to be an important antecedent of attitude toward a website, which consequently affects actual behavior or future intention (Chung, Lee, Lee & Koo, 2015). Green and Pearson (2011) demonstrated that the usability of a website influences several outcomes that are important for firms endeavoring to attract, emotionally engage and hence retain customers.

To date little work has been done to explore the nature of the direct relationship between website usability and attitude toward the site. Moreover, the field of usability has traditionally focused on ease of use and functionality, based on observable cognitive activity. More recently, marketing practitioners and web designers have begun to pay closer attention to these aspects of interaction with the product when evaluating usability (Norman & Ortony, 2003). Yet the direct link between website usability and users’ emotional responses to the online experience remains under-researched. To contribute to bridging this gap in the literature, the present study examines the direct link between users’ evaluation of website usability and their attitude toward the website. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

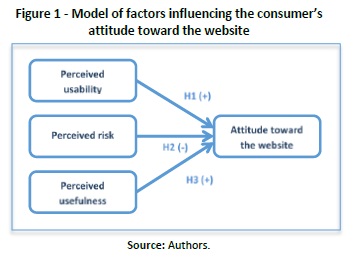

Hypothesis 1. Perceived website usability exerts a positive influence on attitude toward the site.

2.2 Perceived risk and attitude toward the website

The perceived risk variable has been studied from a number of perspectives, beginning with the original approach proposed by Bauer (1960), mainly due to its impact on consumer purchase behavior. Cunningham (1967) expanded the concept, arguing that this variable comprises the individual’s subjective feeling of uncertainty at the possibility of an unfavorable consequence and the magnitude of the unfavorable consequences of the action, such as financial or time losses (Cox, 1967). Other authors, such as Dowling and Staelin (1994), divide perceived risk into two further components, depending on whether it relates to the product category or to a specific product or brand. These concepts are similar to inherent risk and manageable risk, respectively.

As regards the antecedents of this variable, the type and degree of risk perceived in different goods and services are influenced by factors relating to: the attributes of the product in question (Mitra, Reiss & Capella, 1999); differences in the personalities of individuals (Zinkham & Kirande, 1991); and their demographic characteristics (Mitchell & Boustani, 1993), cultural characteristics (Verhage, Yavas, Green & Borak, 1990) and social characteristics (Hugstad, Taylor & Bruce, 1987).

When perceived risk is studied in the context of service perceptions, Laroche, Bergeron and Goutaland (2003) affirm that services are not always perceived as more risky than goods. Although the intangibility of the former does heighten the perception of risk, this is not caused by the intangibility of the physical dimension but rather by the mental dimension. Hence, a good that is mentally intangible (software) may actually be perceived to be more risky than a mentally intangible service (electronic banking, for instance).

The ever-increasing penetration of the Internet has brought with it a series of risks, including: financial risk or the uncertainty provoked by making credit card payments (Maignan & Lukas, 1997); product-associated risks (Bhatnagar, Misra & Rao, 2000); the time required to locate the necessary information (potentially greater than in traditional purchasing outlets) (Bhatnagar & Ghose, 2004; Pappas, 2016); and privacy concerns (Pappas, 2016). Within this context, numerous works have examined the existence of perceived risk to analyze how users accept and process the information they receive online (Featherman & Pavlou, 2003; Wakefield & Whitten, 2006) and in their online transactions (Chang et al., 2013; Mohseni et al., 2016), and how perceived risk affects users’ attitudes toward the website (Jarvenpaa, Tractinsky & Saarinen, 1999).

It has been demonstrated that perceived risk is a key variable in user perceptions of a website (Chang et al., 2013) and that there is a significant relationship between perceived risk and intention to purchase (Green & Pearson, 2011). Several different studies have shown that perceived risk has a negative effect on attitude toward online purchasing, due to the intangibility of the product (Kolesar & Galbraith, 2000). It is therefore to be assumed – as demonstrated by Hsieh and Tsao (2014) – that there is an inverse relationship between the user’s perception of risk during the browsing process and their attitude toward the website in question. On this basis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2. Perceived online risk exerts a negative influence on attitude toward the website.

2.3 Perceived website usefulness and attitude toward the site

Perceived usefulness has been studied widely as a determining factor in user acceptance for technology systems (Ben-Bassat, Meyer & Tractinsky, 2006). Davis (1989) asserts that perceived usefulness is influenced by a number of external variables. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) conceives perceived usefulness as a direct determining construct of attitude, which affects intention.

More specifically, perceived usefulness is considered to be a source of extrinsic motivation that influences the usage of the Internet, via attitudes and intentions (Taylor & Todd, 1995). A number of models provide theoretical justification and empirical evidence for the direct links between usefulness and intention (Bagozzi, 1982). Meanwhile, several studies corroborate the assertion that perceived usefulness is a powerful determinant of attitude (Lee, Kozar & Larsen, 2003).

The TAM, which has been extensively developed in the literature and used to predict user acceptance of the World Wide Web, highlighted the need to introduce the concept of “self-efficacy” (O’Cass & Fenech, 2003). More recent studies have applied the model to acceptance of the Internet (Lederer, Mauping, Sena & Zhuang, 2000) and e-commerce (Gefen & Straub, 2000), as well as to analyzing users’ choice of website and virtual services (Featherman & Pavlou, 2003).

The reasoning behind other models based on the TAM (see Davis, 1989) and on the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) is that beliefs exert a direct and positive effect on attitudes toward usage. In other words, perceived usefulness influences attitudes toward use of the system. In this regard, it is worth noting that one of the most significant adaptations of the TAM was that of Castañeda et al. (2007), who proposed that website perceived usefulness determines user attitude toward the site. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3. Perceived website usefulness exerts a positive influence on attitude toward the site.

In light of the proposed hypotheses, the model defined in this study is presented in Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1 Procedure

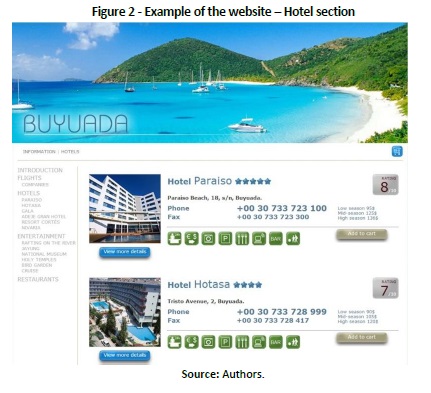

The study was conducted in 2011. A professional website promoting a fictitious tourist destination (with its own domain name) was used as the framework for the experiment. Using a fictitious name automatically removed the possibility of the participant having had prior experience or beliefs pertaining to the destination (Dahlén, Friberg & Nilsson, 2009). The site was hosted via a domain pertaining to the researchers, enabling them to simulate natural browsing conditions at all times for the subjects (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

The participants were asked to browse through the website and put together their own tourism package based on a combination of four components – an outward flight, a return flight, hotel accommodation and a restaurant – from the multiple options on offer. The rationale for asking participants to fulfill this task was to simulate user behavior when presented with varied information and alternatives online while contracting a tourism package. In each of the four components there was one optimum option, hence the number of “correct” choices in terms of selecting the optimum option varied between 0 and 4. Given that the study aim required participants to process the information presented on the website in some depth, it was a condition of participation in the final sample that they should successfully select between three and four of these optimum choices. Once the users had completed the task and browsing was complete, they were redirected to the questionnaire, covering the four variables under study.

In line with the recommendations of several authors (Crespo- Almendros, Del Barrio-García & Alcántara-Pilar, 2015), participants were offered an incentive to achieve the optimum result for the task and complete the subsequent questionnaire, in the form of a free prize draw to win an iPod Touch. The rationale behind the incentive was to encourage them to browse through the site carefully and make the effort to process all of the information.

The reasoning behind choosing the tourism sector as the focus for the research was that the World Tourism Organization (WTO) has declared that the key to success in this medium as a source of tourism information is to swiftly identify consumers’ needs and establish direct contact with tourists. Furthermore, the WTO has asserted that websites should offer tourists information that is comprehensive, personalized and up-to-date (Wen, 2012). The Internet is one of the main sources of information used by tourists when making travel plans (Neuhofer, Buhalis & Ladkin, 2014). This behavior can be considered habitual and common throughout the great majority of countries and cultures, hence the decision to use this sector for the purposes of the present study.

3.2 Participants

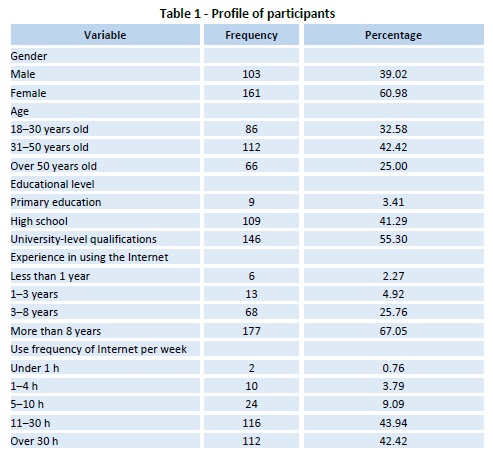

The characteristics of the experiment made it impossible to use random sampling. Therefore, a similar methodology to that implemented previously in many other works was used (O´Connor, Bansal‐Travers, Carter, & Cummings, 2012; Valenzuela et al., 2012). Participants were selected via an Internet user panel using data issued by the UK's Office for National Statistics relating to the socio- demographic profile of users between the ages of 18 and 64. The final sample comprised 264 Internet users, comprising 39.02% male participants and 60.98% female. The sample represented an average age of 39.95 years. The participants were highly experienced in using the Internet, with 86.36% browsing online for over ten hours a week. As regards educational level, the sample was divided into three sub-groups: primary education, high school and university-level qualifications. Over 55% of the sample were in this latter sub-group. The detailed demographic profile of the sample is shown in Table 1.

3.3 Measures

The measures used in the study were adapted from prior studies. In order to evaluate the scales a multigroup confirmatory factorial analysis was conducted. Likewise, the discriminant validity of the constructs in each group was tested following the procedure proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981).

3.4 Data analysis

To determine the relationship between the variables considered in the study, a multiple regression analysis was conducted applying the ordinary least squares method, which produces solutions that are easily interpretable. The variable of interest was attitude toward the website and the independent variables were perceived usability, perceived risk and perceived usefulness. The values for each variable were determined by the sum of the scores given by the participants, on a seven-point Likert scale, to the items considered within that variable (there being three items for attitude toward the website, seven for perceived usability, three for perceived risk and four for perceived usefulness). Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 21.

3. Results

4.1 Reliability and validity of the scales

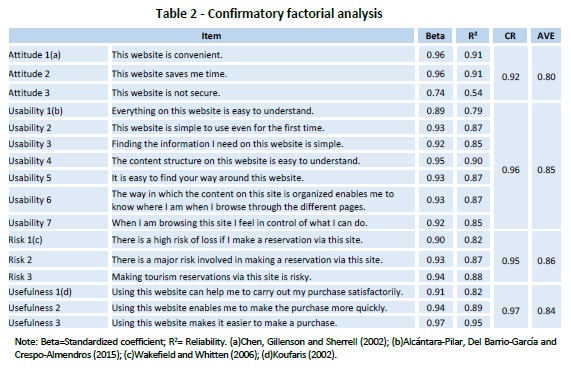

With regard to evaluating the scales, their reliability was demonstrated as all the parameters were found to be significant and their individual reliability was above 0.50. Composite reliability (CR) and variance extracted (AVE) values for the different scales were, in all cases, significantly above the recommended values of 0.70 and 0.50 respectively (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & William, 1995) (see Table 2).

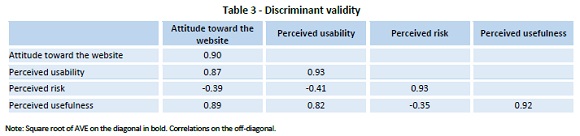

The discriminant validity of the different constructs was also proven since the square root of the variances extracted was higher than the correlations between constructs (see Table 3).

4.2 Regression analysis results

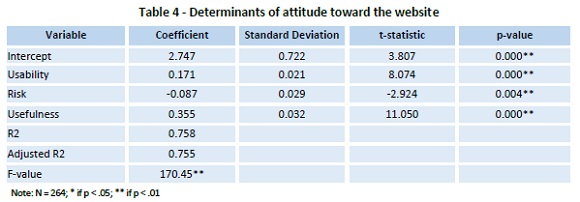

The regression analysis provided strong empirical evidence to support the proposed hypotheses. The proposed model performed well, explaining over 75% of the variation in attitude toward the website, and all the independent variables were found to be statistically significant at the 0.01 level (see Table 4).

Specifically, perceived usability and perceived usefulness have a significant positive impact on attitude toward the website (with coefficients of 0.171 and 0.355, respectively). And the effect of perceived risk on the variable of interest is negative (the value of the coefficient being -0.087). Therefore, the three hypotheses are supported empirically.

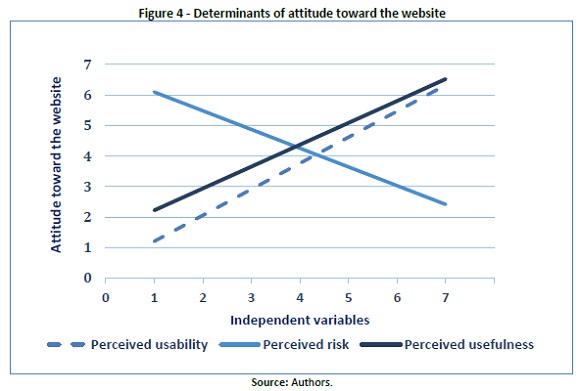

Figure 4 represents the influence of perceived usability, perceived risk and perceived usefulness on attitude toward the website. It can be seen that while for higher values the effect of perceived usability and perceived usefulness on the dependent variable tends to equalize, for lower values the lack of website usability has a higher impact on the consumer’s attitude.

5. Discussion

Within an increasingly competitive market and a globalized world, operating a successful website is essential for firms seeking to survive and grow (Porcu, del Barrio-García, Alcántara-Pilar, & Crespo-Almendros, 2016). Regardless of whether the core business is operated digitally or not, the functionality of a firm improves when operating online as services and information can be provided 24 hours a day – meaning that consumers can be made aware of the firm and its products without the restrictions of time and place.

But firms are no longer content to simply have an online presence: they expect their websites to act as business tools. And for this, it is crucial for them to have a website towards which the consumer develops a positive attitude. In this context, the present study examines the influence of the website’s characteristics (usability, risk and usefulness perceived while browsing) on the consumers’ attitude toward it. Although several works have addressed separately the role of perceived website usability (Romanazzi, Petruzzellis & Iannuzzi, 2011), perceived risk online (Kim, Kim & Shin, 2009) and perceived usefulness (Castañeda et al., 2007), the relationships to the perception of website quality remain unclear. In this regard, the present study provides a relevant contribution from both theoretical and practical perspectives, analyzing empirically the antecedent effect of these factors on the formation of attitude toward a website.

5.1 Conclusions and managerial implications

The findings from the study raise several interesting issues worthy of mention. First, it was affirmed that perceived usability has a significant and positive effect on consumers’ attitudes toward a website. Business managers must therefore ensure that the firm’s website is easy to understand, simple to use and well-organized, with accurate and helpful information, as this leads to a more favorable perception of the website as a whole. This favorable perception may, in turn, positively influence purchase intention – and therefore contribute to business success.

The findings also demonstrate that perceived risk is negatively associated with attitude toward the website, such that the lower the perceived risk the more positive the perception of the website the consumer will have. Therefore, it is vital that designers create a reliable website, as if consumers believe the site to pose a risk their attitude toward it will be negatively affected – and so too, as a consequence, will their purchase intention.

Furthermore, perceived website usefulness was found to positively influence attitude toward the site. Thus, firms should provide the features consumers need via their websites, taking into account who the target users are and reviewing and updating the site content to ensure consumers always find relevant and useful information.

In summary, a poor design can negatively affect consumers’ attitudes toward a website and, in turn, their purchase intention. In order not to lose potential consumers, firms must make every effort to avoid creating website that may be perceived as confusing, unsafe or unhelpful. By contrast, if the website characteristics are optimal the firm will be more likely to succeed.

5.2 Limitations and directions for future research

Despite the contribution that this study makes, it is subject to some limitations that could be addressed in future studies. First, only three variables related to website features were coded. Other variables may influence the user perceptions of a website. Also, it would be interesting to take into account the cultural factor as it is highly probable that cultural values would significantly moderate the effect of perceived usability, perceived risk and perceived usefulness on attitudes toward a website. Finally, a longitudinal study, rather than this cross-sectional study, could help to examine the issues of temporal precedence.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Alcántara-Pilar, J. M., Barrio-García, S. D., & Crespo-Almendros, E. (2015). Cross-cultural comparison of the relationships among perceived risk online, perceived usability and satisfaction during browsing of a tourist website. Tourism & Management Studies, 11(1), 15-24. [ Links ]

Bagozzi, R. P. (1982). A field investigation of causal relationships among cognition, affect, intentions, and behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 562–584. [ Links ]

Bauer, R. A. (1960). Consumer behavior as risk taking. In R. S. Hancock (ed.), Dynamic marketing for a changing world (pp. 389–398). Chicago: American Marketing Association. [ Links ]

Ben-Bassat, T., Meyer, J. & Tractinsky, N. (2006). Economic and subjetive measures of the perceived value of aesthetics and usability. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 13(2), 210–234. [ Links ]

Bevan, N. (2009). International standards for usability should be more widely used. Journal of Usability Studies, 4(3), 106–113. [ Links ]

Bhatnagar, A. & Ghose, S. (2004). Segmenting consumers based on the benefits and risks of internet shopping. Journal of Business Research, 57(12), 1352–1360. [ Links ]

Bhatnagar, A., Misra, S. & Rao, H. R. (2000). On risk, convenience, and Internet shopping behavior. Communications of the ACM, 43(11), 98–105. [ Links ]

Brave, S. & Nass, C. (2008). Emotion in human computer interaction. In

A. Sears & J. A. Jacko (eds.), The human-computer interaction handbook: Fundamentals, evolving technologies and emerging applications (pp. 77–92). New York: CRC Press.

Cappel, J. J. & Huang, Z. (2007). A usability analysis of company websites. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 48(1), 117–123. [ Links ]

Castañeda, J. A., Muñoz-Leiva, F. & Luque, T. (2007). Web acceptance model: Moderating effects of user experience. Information & Management, 44(4), 384–396. [ Links ]

Chang, M. K., Cheung, W. & Tang, M. (2013). Building trust online: Interactions among trust building mechanisms. Information & Management, 50(7), 439–445. [ Links ]

Chen, L., Gillenson, M. L. & Sherrell, D. L. (2002). Enticing online consumer: An expected technology acceptance perspective. Information & Management, 39(8), 705–719. [ Links ]

Chung, N., Lee, H., Lee, J. S. & Koo, C. (2015). The influence of tourism website on tourists' behavior to determine destination selection: A case study of creative economy in Korea. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 96, 130–143. [ Links ]

Cox, D. F. (1967). Risk taking and information handling in consumer behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Crespo-Almendros, E., Del Barrio-García, S. & Alcántara-Pilar, J. M. (2015). What type of online sales promotion do airline users prefer? Analysis of the moderating role of users’ online experience level. Tourism & Management Studies, 11(1), 52–61.

Cunningham, S. M. (1967). Perceived risk and brand loyalty. In D. F. Cox (ed.), Risk taking and information handling in consumer behavior (pp. 507–523). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dahlén, M., Friberg, L. & Nilsson, E. (2009). Long live creative media choice. Journal of Advertising, 38(2), 121–129. [ Links ]

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and user acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [ Links ]

Dowling, G. R. & Staelin, R. (1994). A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 119–134. [ Links ]

Featherman, M. S. & Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59(4), 451–474. [ Links ]

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [ Links ]

Gefen, D. & Straub, D. W. (2000). The relative importance of perceived ease-of-use in IS adoption: A study of e-commerce adoption. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 1, 1–28. [ Links ]

Green, D. T. & Pearson, J. M. (2011). Integrating website usability with the electronic commerce acceptance model. Behaviour & Information Technology, 30(2), 181–199. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. & William, C. B. (1995).

Multivariate data analysis with readings. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Hsieh, M. T. & Tsao, W. C. (2014). Reducing perceived online shopping risk to enhance loyalty: A website quality perspective. Journal of Risk Research, 17(2), 241–261. [ Links ]

Hugstad, P., Taylor, J. W. & Bruce, G. D. (1987). The effects of social class and perceived risk on consumer information search. Journal of Services Marketing, 1(1), 47–52. [ Links ]

Internet World Stats (2016). World internet usage and population statistics. Retrieved February 11, 2016, from http://www.internetworldstats.com [ Links ]

ISO (1998). ISO 9241: Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals. Part 11 – Guidance on usability. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. [ Links ]

Jarvenpaa, S. L., Tractinsky, N. & Saarinen, L. (1999). Consumer trust in an Internet store: A cross‐cultural validation. Journal of Computer‐ Mediated Communication, 5(2), 1–33. [ Links ]

Kim, H., Kim, T. & Shin, S. W. (2009). Modeling roles of subjective norms and e-trust in customers' acceptance of airline B2C e-commerce websites. Tourism Management, 30(2), 266–277. [ Links ]

Kolesar, M. B. & Galbraith, R. W. (2000). A services‐marketing perspective on e‐retailing: Implications for e‐retailers and directions for further research. Internet Research, 10(5), 424–438. [ Links ]

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 205–223. [ Links ]

Laroche, M., Bergeron, J. & Goutaland, C. (2003). How intangibility affects perceived risk: The moderating role of knowledge and involvement. Journal of Services Marketing, 17(2), 122–140. [ Links ]

Lederer, A. L., Maupin, D. J., Sena, M. P. & Zhuang, Y. (2000). The technology acceptance model and the world wide web. Decision Support Systems, 29(3), 269–282. [ Links ]

Lee, Y., Kozar, K. A. & Larsen, K. R. T. (2003). The technology acceptance model: Past, present and future. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 12(1), 752–780. [ Links ]

Maignan, I. & Lukas, B. (1997). The nature and social uses of the Internet: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 31(2), 346–371. [ Links ]

Mazaheri, E., Richard, M. & Laroche, M. (2011). Online consumer behavior: Comparing Canadian and Chinese website visitors. Journal of Business Research, 64(9), 958–965.

Mitchell, V. W. & Boustani, P. (1993). Market development using new products and new customers: A role for perceived risk. European Journal of Marketing, 27(2), 18–33. [ Links ]

Mitra, K., Reiss, M. & Capella, L. (1999). An examination of perceived risk, information search and behavioral intentions in search, experience and credence services. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(3), 208–228. [ Links ]

Mohseni, S., Jayashree, S., Rezaei, S., Kasim, A., & Okumus, F. (2016). Attracting tourists to travel companies’ websites: the structural relationship between website brand, personal value, shopping experience, perceived risk and purchase intention. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1200539

Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2014). A typology of technology‐ enhanced tourism experiences. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(4), 340-350. [ Links ]

Nielsen, J. & Coyne, K. P. (2001, February 15). A useful investment: Usability testing costs - but it pays for itself in the long run. CIO Magazine. Retrieved April 27, 2013, from http://www.cio.com/archive/021501/et_pundits.html [ Links ]

Norman, D. A. & Ortony, A. (2003, November). Designers and users: Two perspectives on emotion and design. Paper presented at the Symposium on foundations of interaction design. [ Links ] Ivrea, Italy.

O’Cass, A. & Fenech, T. (2003). Web retailing adoption: Exploring the nature of internet users web retailing behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 10(2), 81–94. [ Links ]

O'Connor, R.J., Bansal‐Travers, M., Carter, L.P. & Cummings, K.M. (2012). What would menthol smokers do if menthol in cigarettes were banned? Behavioral intentions and simulated demand, Addiction, 107 (7), 1330-1338. [ Links ]

Palmer, J. (2002). Web site usability, design, and performance metrics.

Information Systems Research, 13(2), 151–167.

Pappas, N. (2016). Marketing strategies, perceived risks, and consumer trust in online buying behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29, 92–103. [ Links ]

Porcu, L., del Barrio-García, S., Alcántara-Pilar, J. M., & Crespo- Almendros, E. (2016). Do adhocracy and market cultures facilitate firm- wide integrated marketing communication (IMC)? International Journal of Advertising, 36(1), 121-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1185207 [ Links ]

Romanazzi, S., Petruzzellis, L. & Iannuzzi, E. (2011). Click & experience. Just virtually there’. The effect of a destination website on tourist choice: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(7), 791–813.

Schmidt, K. E., Liu, Y. & Sridharan, S. (2009). Webpage aesthetics, performance and usability: Design variables and their effects. Ergonomics, 52(6), 631–643. [ Links ]

Seffah, A. & Metzker, E. (2004). The obstacles and myths of usability and software engineering. Communications of the ACM, 47(12), 71–76. [ Links ]

Shackel, B. (1991). Usability - context, framework, design and evaluation. In B. Shackel & S. Richardson (eds.), Human factors for informatics usability (pp. 21–38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sonderegger, A. & Sauer, J. (2010). The influence of design aesthetics in usability testing: Effects on user performance and perceived usability. Applied Ergonomics, 41(3), 403–410. [ Links ]

Taylor, S. & Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 144–176. [ Links ]

Thüring, M. & Mahlke, S. (2007). Usability, aesthetics and emotions in human–technology interaction. International Journal of Psychology, 42(4), 253–264. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, S., Kim, Y. & De Zúñiga, H.G. (2012). Social networks that matter: exploring the role of political discussion for online political participation, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24 (2), 163-184. [ Links ]

Verhage, B. J., Yavas, U., Green, R. T. & Borak, E. (1990). The perceived risk-brand loyalty relationship: An international perspective. Journal of Global Marketing, 3(3), 7–22. [ Links ]

Wakefield, R. L. & Whitten, D. (2006). Examining user perceptions of third-party organization credibility and trust in an e-relatier. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 18(2), 1–19. [ Links ]

Wen, I. (2012). An empirical study of an online travel purchase intention model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(1), 18-39. [ Links ]

Zinkham, G. & Kirande, P. (1991). Cultural and gender differences in risk-taking behavior among American and Spanish decision makers. Journal of Social Psychology, 131(5), 741–742. [ Links ]

Received: 13 January 2017

Revisions required: 12 May 2017

Accepted: 23 October 2017

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the financial help provided via a research project of group ADEMAR (University of Granada) under the auspices of the Andalusian Program for R&D, number P12-SEJ2592, and Research Program from the Faculty of Education, Economy and Technology of Ceuta.