1. Introduction

Culture is considered by many authors to be a fundamental pillar in tourist activity, and this tourist sector is called cultural tourism. Tourism consumption of heritage, both material and immaterial, is a lever for the creation of different types of cultural tourism (OECD, 2009). Traditions, monuments, music, dance, and arts give life to cultural tourism, constituting essential components in the tourism product, attracting millions of tourists to tourist destinations (Zouni, Karlis, & Georgaki, 2019).

The festival sector is one of the fastest-growing and most popular sectors in the touristic industry, with emphasis on cultural exchange at international, national and local levels (Carvalho, 2017; Stankova & Vassenska, 2015). This type of tourist attraction refers to events that in their amplitude involve both artists, visitors and participants, sharing the unique cultural perceptions in their various components, such as history and tradition, cooking and drinking, music and dance (Stankova & Vassenska, 2015). Festivals have had an important impact on both tourism development and the economic development of the regions contributing to an increase in income, supporting existing businesses, and encouraging new businesses in the places, thus contributing to government revenues (Dwyer, Forsyth, & Spurr, 2005; Huang, Li, & Cai, 2010).

Kruger and Petzer (2008) explain that arts festival can be classified as a thematic event that takes place in a particular community or a celebration that encompasses art forms and artistic events that, together with tourism, promote experiences and enrich local hospitality.

Dance, considered a timeless and universal phenomenon, constitutes a crucial role in the culture of the human being, it is a form of communication and body expression, representing feelings, ways of thinking and living at various moments in the life of the individual. Dance has been a cultural element with a strong emphasis in society throughout history (Zouni et al., 2019), being a very representative element in the context of festivals.

Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry (1985, 1988) pointed out that the quality perceived by the tourist becomes an important differential factor and a strong instrument of competitiveness of the tourist destinations. A good performance of services will strengthen competitiveness and promote high-quality perception, which will, therefore, positively influence the tourist's behaviour and future intentions.

Baker and Crompton (2000) studied the relationship between the festival quality, festival satisfaction and the behavioural intentions of its participants, through the analysis of four dimensions of festival quality, namely: generic characteristics (festival characteristics), specific entertainment resources, information sources (such as printed programs and information) and comfort conditions for festival participants. These authors verified that the sources of information and comfort conditions (such as hygiene), taking into account that they are considered basic components of the festival can only generate dissatisfaction if they are absent or function poorly; and that increasing the quality of performance positively influences behavioral intentions, and that visitor satisfaction increases the interpretive power of quality.

On the other hand, motivation is considered one of the essential elements in the decision-making process of the tourism consumer (Cooper, Fletcher, Fyall, Gilbert, & Wanhill, 2008).

Deepening the knowledge of festivals is very important to improve the services provided and increase loyalty in this type of events as they are considered increasingly important elements of attractive destinations. However, to our best knowledge, there are no studies in the context of performing arts festivals that analyse the differences between motivation, quality, satisfaction and loyalty.

Considering this, our research has as main objective to analyse and compare the levels of motivation, quality, satisfaction and loyalty of the participants of two performing arts festivals, namely Andanças Festival, Portugal, and La Sierra International Festival, Spain. We consider that the festivals selected for our study are representative in festival tourism, constituting important elements of attraction for the regions where they are developed, promoting their material and immaterial cultural heritage, having the particularity of, besides making traditional dance and music known, both nationally and internationally, participants can have active participation in their experience during the festival.

2. Literature review

2.1. Performing arts festivals

For Cooper et al. (2008), festivals are considered human-made attractions or products in the event's area. On the other hand, Tenan (2002) considers that events mean a special occasion, organised and planned in advance, which bring people together in a certain space and period of time with common interests.

Carvalho (2017) mentions that event tourism is part of the temporary cultural manifestations, fundamental in the attraction of the media, in the renewal of the public and in the development of the local economy, with many loyal participants. As examples of event tourism, the same author highlights international exhibitions, music festivals, theatre or dance, historical shows or carnivals, and their audience is general, amateur and sensitive to the specific content of each event.

Carvalho (2017), Kruger and Petzer (2008), and Stankova and Vassenska (2015) highlight festival tourism as increasing considerably in the last years. This type of event is usually held in the same places, attracting a significant number of participants, motivated by the type of festival. Kruger and Petzer (2008) point out that arts festivals are considered as a very popular way of spending free time. Local festivals and special events are used throughout the world as key elements of regional development strategies, recognised for giving an important contribution to local economic development, namely, for tourism promotional opportunities, for commercial results achievement and domestic investment increase in the host regions (Getz, 2007; Van de Wagen, 2005), and, according to several authors (Boo & Busser, 2006; Huang et al., 2010; Kotler, Haider & Rein, 1993), also contributes to the increase of the touristic season.

For Devesa, Báez, Figueroa, & Herrero (2012), cultural festivals are the most representative of cultural heritage, noting that they have been increasing in recent years in the world. Most regions have one or more festivals dedicated to some artistic manifestation, whose main mission is to promote, present, disseminate and/or preserve the local culture, to contribute to the improvement of the destination's image, to capture a larger number of tourists, and to allow local economic development.

Timothy (2011) argues that music and dance festivals, religious festivals and art shows are important celebrations of culture that attract many visitors, both local and foreign. He also stresses that performing arts and art in general are a crucial part of the product of cultural heritage, which forms part of the so-called living culture by enhancing intangible cultural heritage around the world.

Dance has assumed a prominent position in festival tourism, where the main motivation for individuals to attend dance and traditional music festivals is undoubtedly the possibility of experiencing dance, either passively or actively, depending on one's interests (Zouni et al., 2019).

2.2 Motivation, service quality, satisfaction and loyalty in festivals

One of the most well-known theories about motivation focused on the general human needs, which are scattered throughout life, is Abraham Maslow's theory, known as the Maslow Pyramid, or Maslow's Theory. According to Maslow (1970), this theory presents a hierarchy that includes five types of needs (physiological needs, security needs, love and security needs, esteem needs and self-realisation need). The top-level needs are met when the next lower level has already been completed.

According to Puertas (2004), it is from the third level, where the social needs are met, that the conditions for tourism to emerge in the life of the individual, as a way of social and cultural status and to reach the goal to access the higher levels of the Maslow pyramid are met, such as those of esteem and self-realisation. Puertas (2004) also considers that achieving the tourism experience is a facilitating way to achieve these last two levels, and the tourist motivations correspond to the answers that a tourist will give to the question "Why do I like to travel?".

Gutiérrez and Bosque (2010) report that there is a set of attraction factors, formed by a group of attributes of the tourist destination that originates a motivational power leading the individual to the desire of travelling.

For some authors (Deci, 1992; Sims, Fieneman, & Gabriel, 1993), motivation has been analysed as a psychological mechanism that guides the direction, intensity, and persistence of behaviour, and, for Weihrich and Koontz (1994) motivation consists of a set of wishes, needs, wants and similar forces. Cooper et al. (2008) consider that motivational forces allow the tourist to make decisions about their travel and tourist experiences, and thus the motivation is considered as one of the basic elements in the decision process of the tourist consumer. The perception that the product (activity or tourist destination) will satisfy the need is decisive for the travel decision (Henriques, 2003).

Almeida and Araújo (2017) also argue that in tourism, the motivation to travel and to experience is always present in the choice and action of the individual, and the motivations associated with tourism are considered as the set of psychological needs or forces that predetermine the individual to participate in tourism activity. Tourist motivation is thus based on intrinsic forces that influence the person's decision of carrying out a specific tourist activity.

Regarding festivals, specifically performing arts, if participants are motivated to choose this type of festival they perceive the festival as having a higher quality, that is, when participants choose these festivals for their concept, their motivation seems to be more focused on quality and the context of the experience, as well as the interaction with other participants and with the people who provide all the experience (Amorim, Jiménez-Caballero, & Almeida, 2019).

In 1982, Churchill and Surprenant defined service quality as testimonies of opinion or performance of attributes. Parasuraman et al. (1985) considered that quality is analysed through the perceptions and expectations that, on the one hand, the individual has, and on the other hand, obtains from a particular experience.

The SERVQUAL model and scale, developed by Parasuraman et al. (1985), consists of the difference between consumers' expectations and their perceptions of quality. In 1985, an exploratory study was conducted showing that consumers evaluated quality using the same general criteria, regardless of the type of quality. Parasuraman et al. (1985) arrived at these criteria using a scale made up of 22 items created to group five dimensions, namely, tangibility (physical appearance of the site, equipment, personnel and communication material), reliability (ability to provide the promised service transparently and accurately), responsibility (willingness to serve customers and provide a fast service), security (knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to convey trust) and empathy (consideration and personalised attention in customer service), which reflect quality.

The model seeks to identify gaps or gaps, i.e. the difference between expectations and what is received by customers. And, although this scale has been developed taking into account some particular sectors, it can be applied to any organisation providing services, having to make the necessary adaptations to the reality of each investigation (Parasuraman Berry, & Zeithaml,1991).

The quality of the festival has been analysed in several studies as a multidimensional construct. In particular, Yoon, Lee and Lee (2010) developed a study in which, for the definition of festival value, five important dimensions of festival quality were identified: informational service, program, souvenirs, food, and facilities. Son and Lee (2011) also developed a study, in which the festival quality included general characteristics, conditions of comfort and socialisation. Wu, Wong and Cheng (2014) found that festival quality was based on interaction quality, physical environment quality, outcome quality and access quality. Besides this quality component, Wong et al. (2014) identified one more quality component, which was program quality.

Several studies have analysed the relationship between quality and satisfaction, noting that the quality perceived by the individual is a precedent of satisfaction (Amorim et al., 2019, Appiah-Adu, Fyall &, Singh, 2000; Baker & Crompton, 2000; Chen & Chen, 2010; Chen & Tsai, 2007; Heung & Cheng, 2000; Kozak & Rimmington, 2000; Lee, Graefe, & Burns, 2004; Wu and Ai, 2016).

Felsenstein and Fleischer (2003) emphasise that the tourism product is the result of a combination of several factors, in which tangible and intangible aspects overlap, and that is essential for the tourist sector to be aware of the consumers' satisfaction, therefore, a constant development in the industry, and the crucial creativity in this process is needed.

According to Parasuraman et al. (1988), satisfaction is related to expectations, which are interpreted as predictions. Boshoff and Gray (2004) pointed out that satisfaction consists mainly in the perceptions of the consumer about the attributes of the product or service, and different consumers will express different levels of satisfaction for the same experience or service. Yoon et al. (2010) report that satisfaction is part of the total consumer experience based on both quality attributes and information (e.g. advertising and price), both of which are controlled by the supplier. According to Giese and Cote (2000), there are three general characteristics integrated into the definitions of satisfaction, namely: 1) consumer satisfaction is a response, an emotional or cognitive judgment; 2) the response refers to a specific focus; and 3) the response is linked to a particular moment (before purchase, after purchase, after consumption, among others).

Moscardo (1996, 1999) considers that the key factor for the satisfaction of tourists is their expectation regarding the services received as well as their knowledge during the visit to the chosen destination. Tourist satisfaction is primarily a function of previous expectations and perceived performance after an experience (Chen & Chen, 2010; Chi & Qu, 2008). Tourists are satisfied when comparisons of their previous expectations with post-trip experiences result in pleasant feelings, whereas they have displeasure feelings when they are not satisfied (Chen & Chen, 2010, Chi & Qu, 2008). If a product or service confirms the customer's initial expectations, this will result in a high level of satisfaction, but if the product or service goes beyond expectations, then the customer will be very satisfied and may have the tendency to repeat the experience (Kotler, 2000). Thus, it appears that this is the main objective, not only that customers are satisfied, but that they want to return thus contributing to loyalty.

In the context of research about festivals, several authors define satisfaction. For example, McDowall (2011) describe satisfaction as "a sum of participants' experiences at the festival" (p. 282). On the other hand, Yoon et al. (2010) describe satisfaction with the festival as the "overall festival value evaluated by the composite of quality dimensions" (p. 337).

Wu et al. (2014) found that in festival management studies, festival quality is considered a key factor influencing festival satisfaction.

Wan and Chan (2013), in a study at a gastronomic festival, have identified eight factors that affect their satisfaction levels, namely: "location and accessibility, food, venue facility, environment/ambience, service, entertainment, timing and festival size".

According to Amorim et al. (2019), in the context of performing arts festivals, the participants will only be satisfied with the festival if they realise that it has quality.

Oliver (1999) suggested that loyalty could be defined as a hierarchy that evolves from cognition (e.g., perceived quality), from affection (e.g., satisfaction) and from a conative component (intention or commitment to consume) to a concept of behavioural loyalty called action loyalty.

Yüksel, Yüksel and Bilim (2010), based on performed studies, found that affective loyalty has a stronger effect on conative loyalty than on cognitive loyalty, which entails clear implications for managers. For example, believing that a destination performs better compared to other destinations can increase the intentions of conative loyalty. However, this increase is expected to be less than that of affective loyalty. Destination authorities are advised to invest in the affective components of the destination, such as destinations' ability to induce positive affect, as this seems to result in a greater probability of becoming the customer's first choice at a future opportunity. Jin and Su (2009) refer that customers may have different thresholds that are not fully captured by satisfaction indexes. Customers choose to recommend or repurchase only when their satisfaction ratings are higher than their recommendation and repurchase limits.

In the context of tourism, satisfaction is a good indicator of the intention to revisit (Petrick & Backman, 2002). The importance of tourist revisiting has been well recognised in the global economy and the attraction of the individual (Truong & King, 2009). Along with the intention to revisit, word-of-mouth communication has been identified as a significant market phenomenon and as a mean by which tourists express satisfaction or dissatisfaction with products (Chen & Chen, 2010; Murray, 1991). Thus, the satisfaction of tourists can lead to the intention of revisiting or making beneficial comments about the destination to other visitors (Chi & Qu, 2008). However, dissatisfied tourists may express harmful comments about a destination and affect its credibility in the market (Reisinger & Turner, 2003).

Concerning festivals, the loyalty of the participants is essential for the success of this type of tourist attraction in the various destinations where they take place (Lee, 2014; Wu et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2011). Concerning performing arts festivals, a study carried out by Amorim et al. (2019) on the role of quality mediator and satisfaction between motivation and loyalty, showed that the motivation to choose a performing arts festival will lead to a greater perception of quality by the tourist and, consequently, will lead to greater satisfaction, which, in turn, will also contribute to their loyalty, a crucial element for the success of this type of event.

3. Research context and methodology

The research process is the foundation that facilitates the orientation of the researcher or/and the team responsible for the research design, implementation and evaluation (Vilelas, 2017). Considering this, the research objectives and hypotheses of our study will be explained below, as well as the case study and sample, the evaluation instrument applied, the data collection process, and the statistical analysis performed.

3.1 Research objectives and hypotheses

This study started from the following research question: What are the differences in motivation, quality, satisfaction, and loyalty between participants of Andanças and La Sierra festivals? So, as the main objective, we intend to analyse and compare the levels of motivation, quality, satisfaction and loyalty of the participants of the two performing arts festivals, Andanças (Portugal) and La Sierra (Spain).

Taking into account the literature review and the characteristics of the festivals under analysis (concept, date of foundation, location, infrastructure, number of participants per edition, among others), we conjectured five research hypotheses:

H1 - It is expected that the participants of the Andanças festival will present higher levels of motivation, compared to the participants of the La Sierra festival;

H2 - It is expected that the participants of the La Sierra festival perceive the festival with more quality, in terms of responsibility and reliability, compared to the participants of the Andanças festival;

H3 - It is expected that the participants of the La Sierra festival perceive the festival with more quality, in terms of tangibility, security and empathy, compared to the participants of the Andanças festival;

H4 - It is expected that the participants of the La Sierra festival present higher levels of satisfaction, compared to the participants of the Andanças festival;

H5 - It is expected that the participants of the La Sierra festival will be more faithful to the festival, compared to the participants of the Andanças festival.

3.2 Case study and sample

Our case study is two performing arts festivals: the Andanças Festival, which takes place in Portugal, and the La Sierra International Festival, which takes place in Spain. These two festivals were chosen because both promote a range of dances and music from all over the world, through shows and workshops that are dynamised during the events, with traditional dance and music being the main attractive elements that motivate people to travel to these events and their destinations.

The Andanças Festival is organised by PédeXumbo Association, and has taken place in several places (in the centres of the places and/or in their proximity), and was first promoted in 1996, in Carvalhais, and in Castelo de Vide between 2013 and 2018. It is an event that takes place in mid-August, between 5 and 8 days, attracting about 20,000 people per edition, has an enclosed space and charges a ticket. This festival is considered very relevant in music and dance in Portugal, which brings together a diversity of artists and audiences, who interact dynamically through traditional practices, reinventing them and fusing them with contemporary artistic expressions. In the year 2019, this festival did not take place and is preparing its return in a new location not yet announced.

The International Festival of La Sierra, also known as FESTISIERRA, is organised by the folkloric group Los Jateros. It is a local event that has been celebrated since 1980 (originally dubbed the Festival of Popular Dances and Songs), in the historic centre of Fregenal de La Sierra, in Badajoz, usually at the end of July and in the first two weeks of August, for approximately 15 days, with about 60,000 participants. This event offers mainly two spaces for the festival, two central squares of Fregenal de La Sierra (Paseo de La Constitucion and Paseo de La Palma), which are freely accessible, with no entrance fee. The highlight of the festival is the evening folk show in the Sierra and folk music festival with groups from different communities and countries that interrelate admirably with the hundreds of participants who come to FESTISIERRA, with Celtic music, the flamenco gala, singers, guitarists and dancers from different locations.

The festivals are known for the opportunity to promote discovery and learning, coexistence and cultural exchange between national and international people, where participants can appreciate and experience various styles of the traditional dance of the world, accompanied by equally traditional music. In addition to music and dance, these two events also include gastronomy, handicrafts, popular games, and street entertainment. The main difference is that Andanças is an event where the possibility for its participants to have direct participation is constant, through a variety of workshops of traditional dance and music, dynamised during the morning and afternoon, and in the collective night dances, while in La Sierra this type of participation, namely more direct participation and involvement of the participants, occurs in a more one-off situation, through workshops that usually take place in the morning.

The sample of our research consisted of the participants of the festivals under study who were willing to collaborate in this work. We applied 549 questionnaires, but only 532 were validated, taking into account the consistency of the answers obtained. Thus, our sample consisted of 297 participants from Andanças and 235 participants from La Sierra.

3.3 Measures

The measurement instrument of this study was the questionnaire survey, whose design was based on the literature review and several theoretical models (Albayraka & Caberb, 2018; Kitterlin & Yoo, 2014; Yi, Fu, Jin & Okumus, 2018; Son & Lee, 2011; Wan & Chan, 2013; Wu & Ai, 2016; Wu et al., 2014; and Yoon et al., 2010), as well as the analysis of validated questionnaires (Gutiérrez, 2005; Almeida A., 2010; Almeida P., 2010; Quintero, 2015).

The questionnaire consists of three parts: the first part refers to the socio-demographic data; the second part refers to the frequency data of the festival; the third part refers to the essential characteristics of the festival, such as motivation, quality, satisfaction and loyalty.

The motivation to choose the festival was assessed through eight items (e.g. "The concept of the festival"; "Knowing and experiencing a diverse number of workshops available"; "Trying out different traditional dances at a national level").

For the quality of services the festival was assessed through seventeen items, for the quality analysis: Tangibility, safety and empathy through eight items (e.g. "The physical structures of the site are in good shape"; "The festival staff have a clean and clean appearance"; "The festival offers a calm and relaxing environment"), and for the Quality analysis: Responsibility and reliability nine items ("Accessibility and signage are the right ones"; "Accommodation is the right ones"; "Workshop schedules are the right ones and are met").

For satisfaction was assessed through eleven items (e.g. "It provides an excellent service"; "The Festival staff surprised me with their service"; "More satisfied with the service than I expected".

For loyalty was assessed through six items (e.g. "I will recommend the festival to those who ask me for advice"; "I will encourage my family and friends to participate in the festival"; "I will continue to participate in this festival even if prices increase".

The scale used in the third part of the questionnaire was a Likert scale of 1 to 7 points, ranging from very unimportant/ I completely disagree (1) to very important/ I completely agree (7).

3.4 Collecting data

The data collection took place in August 2017, and the questionnaire was directly applied by four people during the festivals. At the La Sierra Festival the questionnaire was applied on August 7 and 8, 2017, and at the Andanças Festival the questionnaire was applied on August 9 and 10, 2017. The questionnaires were applied randomly to the participants who showed their willingness to participate in the study, in the festivals' venues, during breaks between activities.

3.5 Data analysis

Data analyses was performed with SPSS Statistics (v.22, IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). The effects with p ≤ .05 were considered statistically significant.

To characterise the sample, measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation) were used. The Chi-square independence test was used to determine if there is a significant relationship between two categorical variables. To test whether the means of two groups in the same continuous variable are significantly different or not, the t- test for independent samples was used.

4. Results

4.1 Sample characterisation

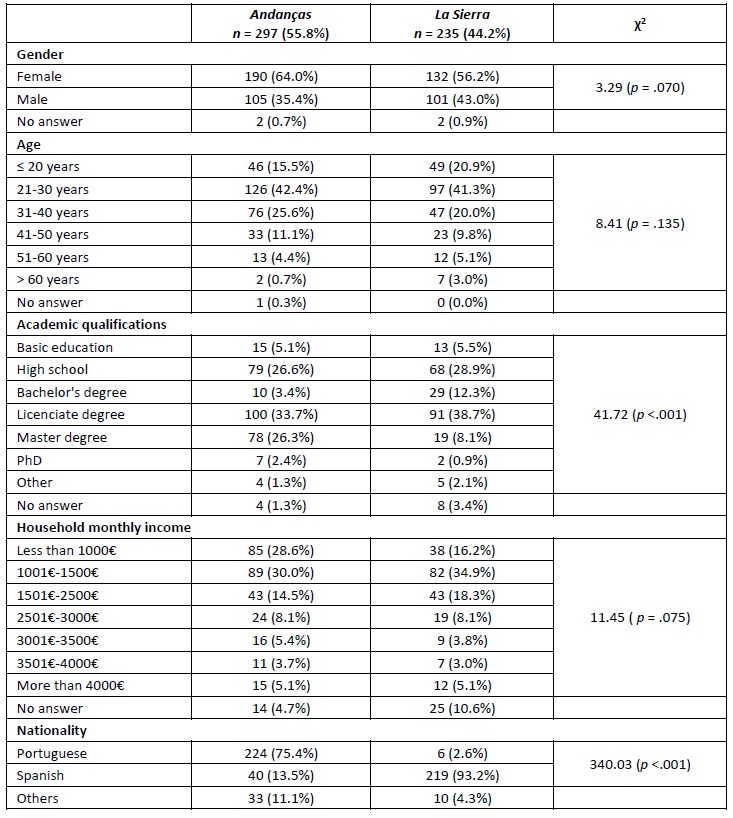

At the Andanças festival, we had 190 (64.0%) female participants, 105 male participants and two people that did not answer the gender question. At the La Sierra festival, we had 132 (56.2%) female participants, 101 male participants, and two people that did not answer the gender question. The most representative age group in both festivals is 21-30 years of age, with 126 (42.4%) participants in the Andanças festival and 97 (41.3%) participants in the La Sierra festival. Regarding the level of education, in both festivals the participants have a high level of education, with 33.7% of graduates in Andanças and 38.7% of graduates in La Sierra. Regarding the monthly income of the household, it was verified that 30% of the participants of the Andanças festival and 34.9% of the participants of the La Sierra festival earned between 1001 euros and 1500 euros. Regarding the nationality of the participants, it was verified that about 75.4% of the participants of the Andanças festival were of Portuguese nationality and 93.2% of the participants of the La Sierra festival were of Spanish nationality.

Data regarding the socio-demographic variables of the participants of each festival are presented in table 1.

With the independence χ2 test we found that the variable academic qualifications of the participants is not independent of the festival [χ2 (6) = 41.72, p < .001)], as well as nationality [χ2 (2) = 340.03, p < .001)]. On the other hand, we verified that the gender, age and monthly income of the participants are independent of the festival.

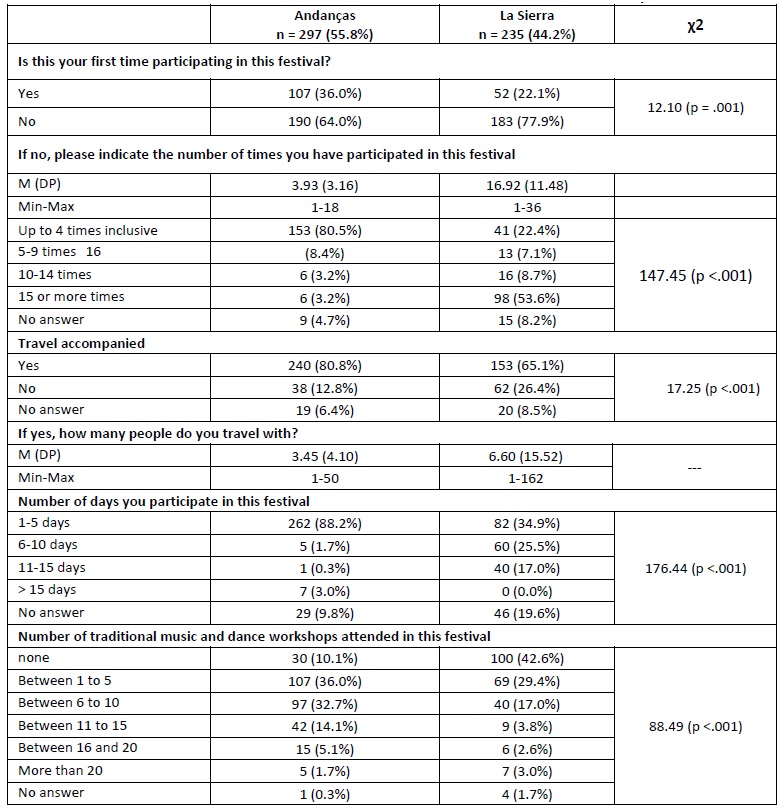

Most participants have attended the festival at least once in previous editions, with the majority of La Sierra participants attending on average 16 or more times at the festival, while the majority of Andanças participants participated on average four times in previous editions.

Regarding the number of traditional dance and music workshops offered by the festivals, most Andanças festival participants attend between 1 and 10 workshops, and only 10% of the participants do not participate in any workshop. On the contrary, 46.4% of La Sierra participants attend between 1 and 10 workshops, and 42.6% of the participants do not take part in any workshop. It also appears that the vast majority of participants from both festivals travel accompanied. Table 2 shows the participants' data regarding their attendance at the respective festival. The χ2 test of independence showed that all the variables related to the attendance in the respective festival are not independent of the festival.

4.2 Comparison between festivals

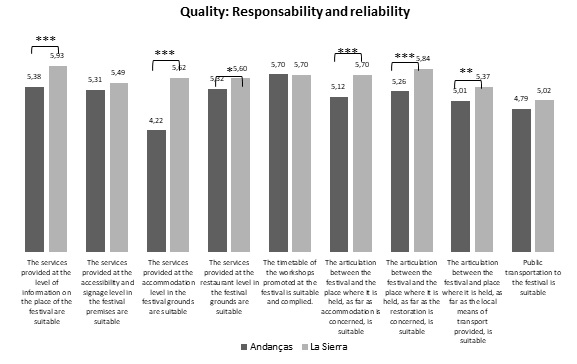

Student's t-test was used to determine if there were differences between the two festivals regarding choice motivation, satisfaction, quality (responsibility and tangibility) and loyalty. There were statistically significant differences in loyalty and quality factors: responsibility and reliability (Table 3), where La Sierra participants scored significantly more on the quality factor: responsibility, reliability and loyalty than the Andanças festival participants.

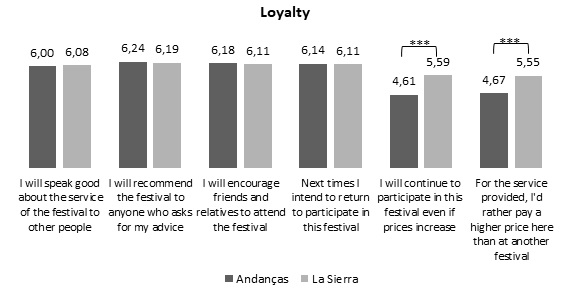

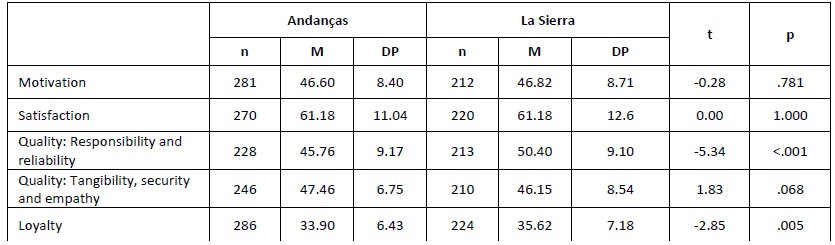

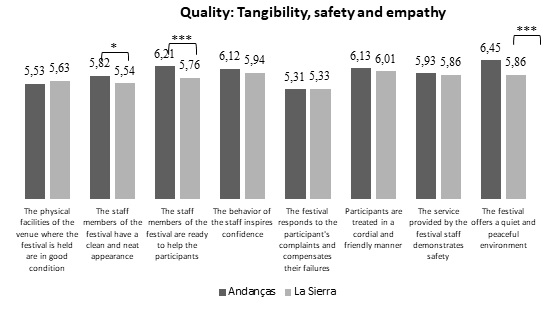

Table 3 T-test to compare motivation, satisfaction, quality and loyalty between the two festivals

Source: Authors.

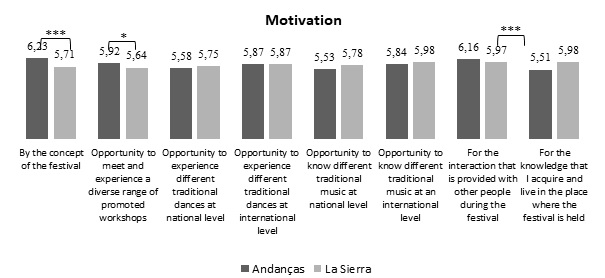

Concerning the variable festival choice motivation (Figure 1), we verified that Andanças festival participants give more importance to the concept of the festival and the opportunity to know and experience a diverse range of promoted workshops. Still, they give less importance to the knowledge they can acquire and experience in the place where the festival is held, compared to the participants of the La Sierra festival.

Concerning quality: tangibility, safety and empathy (Figure 2), Andanças festival participants agree significantly more than the La Sierra festival participants that the staff members of the festival have a clean and neat appearance and that they are ready to help the participants, and even that the festival offers a quiet and peaceful environment.

Figure 2 T-test of the quality: tangibility, safety and empathy items between the two festivals. Note: * p < .05, *** p < .001

Regarding quality: responsibility and reliability (Figure 3), participants at the La Sierra festival agreed, significantly more than participants in the Andanças festival, that the services provided regarding the information on the location of the festival are suitable, that the accommodation services and catering provided in the festival grounds are adequate and that the link between the festival and the place where the festival takes place is appropriate in relation to accommodation, catering and local means of transport provided.

Figure 3 T-test for the quality: responsibility and reliability items between the two festivals. Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

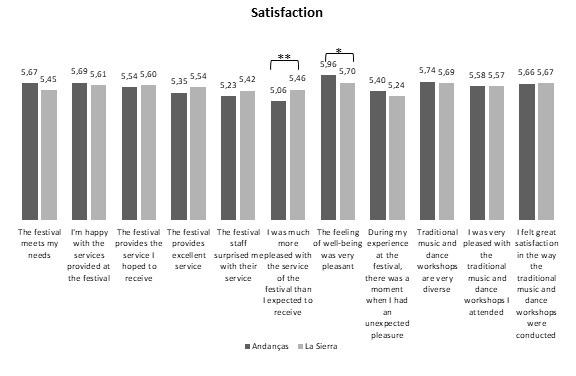

Concerning satisfaction with the service provided at the festival (Figure 4), we found that the participants of the La Sierra festival were much more satisfied with the service of the festival than they expected compared to the Andanças festival participants. On the other hand, Andanças festival participants reported a greater sense of well-being at the festival than participants of the La Sierra festival.

Concerning the loyalty to the festival (Figure 5), La Sierra festival participants, compared to Andanças festival participants, score significantly more on price items, namely that they will continue to participate in the festival even if prices increase and that for the service provided, they prefer to pay a higher price than at another festival.

5. Discussion

In this study, the main objective was to analyse and compare the levels of motivation, quality, satisfaction and loyalty of the participants of the two performing arts festivals, Andanças (Portugal) and La Sierra (Spain). The research hypotheses formulated had the following assumptions: hypothesis 1 was defined, essentially, based on the motivational forces that lead the individual to participate in tourist events, such as festivals, and by the fact that Andanças festival presents a more permanent and dynamic experiential character, through the workshops of traditional dances and music, both nationally and internationally, compared to La Sierra festival, which despite having this component, is in a much smaller scale. Hypotheses 2, 3, 4 and 5 were formulated on the basis of the literature review and history of foundation and evolution of the festivals. La Sierra festival is an event that has been taking place for more years than Andanças (namely for more than 16 years), in a place that has hosted the event since its origin, assuming that the logistic and infrastructure issues can have a more consistent and organised structure, as well as the articulation between the destination and the event's managing entity, regarding Andanças.

In Hypothesis 1, it was assumed that the participants of the Andanças festival have higher levels of motivation, in relation to the participants of the La Sierra festival, was not confirmed, as we did not obtain significant differences in the motivation of the choice of the festival between the participants of the Andanças festival and La Sierra. However, the items analysis showed that Andanças participants give more importance to the concept of the festival and the opportunity to know and experience a diverse range of promoted workshops than the La Sierra participants. This data seems to make sense since most of the Andanças participants attend between 1 to 10 workshops. On the other hand, the La Sierra participants give more importance to the knowledge that they acquire and experience in the place where the festival is held. In terms of experience and knowledge of new traditional dances, both participants give equal importance, which suggests that individuals who choose these types of performing arts festivals are aware of their need and become involved dynamically in an activity that gives them learning and cultural and artistic knowledge opportunities.

In Hypothesis 2, it was assumed that the participants of the La Sierra festival perceive the festival with more quality, in terms of responsibility and reliability, was confirmed, since significant differences were found. These significant differences suggest that the participants of the Spanish festival perceive the festival as having a greater articulation with the location and more accessibility to the festival than the participants of the Portuguese festival. Through the analysis of the quality aspects - responsibility and reliability. it was verified that the participants of the La Sierra festival, compared with the Andanças festival participants, agreed significantly more that the information provided about the location of the festival is adequate, that the services provided at the accommodation and catering level in the festival venue are suitable and that the link between the festival and the site where the festival takes place is adequate for the services: accommodation, catering and local means of transport provided. These differences in the articulation between the festival and the place can be justified taking into account that the location of the La Sierra festival is more central, that is to say, it is held in the historical centre of Fregenal de La Sierra, which allows participants to have easier access, for example, to restaurants and/or mini-markets (which are located near the spaces where the festival takes place), and the accommodation is also easily accessible, as the hotel units are very close to the festival. In Andanças, catering and mini or supermarkets are further away, although there is in the festival grounds a space with places to eat, which is free access. Regarding accommodation, participants have some hotel units near the festival grounds, although many participants opt for camping service that is made available by the organisation.

In Hypothesis 3, it was assumed that the participants of the La Sierra festival perceive the festival with more quality, in terms of tangibility, security and empathy, has not been confirmed, as we did not obtain significant differences. The results obtained may mean that participants at both festivals recognise that staff members inspire security and confidence, are available to help, treating participants in a friendly way. By analysing the items that measure quality - tangibility, safety and empathy, Andanças festival participants agree significantly more than La Sierra festival participants that the staff members of the festival have a clean and neat appearance and are ready to help participants, and that the festival offers a quiet and peaceful environment.

In Hypothesis 4, where it was deduced that the participants of the La Sierra festival have higher levels of satisfaction, in relation to the participants of the Andanças festival, has not been confirmed, since there were no significant differences in relation to satisfaction. However, in the analysis of the items, comparing Andanças participants with La Sierra participants the last are more satisfied with the festival service received than they expected, while Andanças participants reported that the feeling of well-being was more pleasant compared to the La Sierra participants. Concerning the greater satisfaction with the service of the La Sierra festival, we could consider that perhaps participants had a lower expectation concerning the service that they hoped to receive. In relation to the greater sense of well-being reported by Andanças participants, hypothesised that this is due to the fact that they participate more actively and more frequently in the activities and workshops promoted by the festival, which results in a greater and more positive affective reaction to these behaviours.

In Hypothesis 5, where it was deduced that the participants of the La Sierra festival are more faithful to the festival, in relation to the participants of the Andanças festival, it was confirmed, because there were significant differences between festivals in the loyalty factor, in which the participants of the Spanish festival scored significantly more. Although most participants in both festivals are not participating for the first time in the festival, it was found that the participants in the Spanish festival, on average, have participated at least sixteen times in previous editions, in contrast to the average participation of four times in the Portuguese festival. It is assumed that this difference is because the participants of the Spanish festival have greater accessibility, they live closer to the festival venue, and also because La Sierra festival has been held for more years than the Andanças festival. While La Sierra is a festival directed mostly to locals, Andanças festival focuses on attracting participants, both national and international, since it is held in a village in the interior of Alentejo with relatively few inhabitants. Consequently, La Sierra is expected to be attended mostly by individuals who live close to the festival and who do not have to make large trips. In contrast, Andanças participants have to make longer journeys and use various means of public transportation. Analysing the loyalty items, participants of La Sierra festival, compared to participants in Andanças festival, pointed out that they will continue to participate in the festival even if prices increase and considering the service provided, they prefer to pay a higher price in this festival than in another one. These data seem to show that Andanças participants may have less purchasing power, or that the prices that are practised at the Andanças festival are higher than of the La Sierra festival. But another fact that may be relevant is that in Andanças a ticket is paid to enter the premises, while La Sierra is an open-access festival. In addition, it is interesting to note that the monetary issue related to the festival may not affect the intention to recommend the festival to others, but may jeopardise the intention to return to the festival.

6. Conclusions

The events, and specifically festivals, have boosted tourism in its various aspects. These provide, in an organised way, a set of activities that invite participation and develop dynamics of acculturation and endogenisation. Performing arts festivals can boost tourism in the way that they lead to the displacement of people, motivated by the search for artistic, cultural elements, in this case, traditional dance and music, both locally and internationally.

In the specific cases studied, Andanças Festival, in Castelo de Vide, Alentejo, Portugal, and La Sierra International Festival in Fregenal de La Sierra, Badajoz Province, Spain, are socially and culturally excellent examples of approaching people, cultures and revenue-generating producers that enable the development of local communities.

With regard to festivals, specifically performing arts, if the quality of the participant's experience is perceived positively, it will lead to the participant's satisfaction, which in turn will also contribute to their loyalty, the "key ingredient" for the success of this type of event (Amorim et al., 2019). Thus, it is up to the event organisers to analyse and evaluate the performance of the event in order to improve the quality of the service, influencing the whole process of evaluation of the festival by the participant. Therefore, we consider that our study will be an added value for the organisers and managers of events, specifically in what concerns performing arts festivals, because it allows us to have a perception of what the participants value more in terms of their motivations, the quality of services, their satisfaction and loyalty. It is fundamental that the festivals meet the expectations and needs of the participants, thus leading to their loyalty, and consequently, to the success of the festivals, particularly in performing arts.

The current study presents some limitations, highlighting the fact that the study was implemented only in two performing arts festivals, so the results cannot be extrapolated to festivals in other regions. Thus, it would be interesting, in future studies, to see if participants who choose events of performing arts instead of other types of event show differences in the event choice motivation, quality, satisfaction and loyalty.