1. Introduction

With the universal implementation of the reform and opening- up policy in China and increasing public interest in culture and education, museums have become popular tourist stops. In this new era of culture and tourism integration, how can museums, as highly concentrated institutions of cultural resources, better play the role of passing on civilization and culture to the next generation? Several museums, travel agencies, and educational institutions have established businesses around museum resources through research tours, project studies, group tours, and so forth, as part of new cultural and tourism integration projects. Thus, the museum tourism industry is becoming a vital educational part of the tourism industry. As aplicações práticas

são sugeridas com base nos resultados de que a lealdade conativa dos visitantes do museu é relativamente influenciada pela sua conexão emocional e que a excitação emocional pode promover a aceitação do turismo de museus.

The International Council of Museums (ICOM) (Boylan, 2010) defines a museum as a non-profit, permanent institution serving the development of society, which is open to the public, and focuses on the preservation, research, dissemination and exhibition of physical evidence of people and their environment for the purposes of research, education and enjoyment. The museum environment provides researchers with unique backgrounds to explore service quality standards. In a museum, unlike other tourism destinations, what matters is not achieving the greatest profits or most effective management. Because of its unique qualities, a museum’s stakeholders are more concerned about the collection than visitors’ needs.

However, does visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty not matter for the museum industry at all? According to McLean (1994), many museum marketers believe that customers are essential in their organization’ s success. As the importance of museum visitors is now recognized, the museum industry has begun to consider the factors involved. If marketers can relate these factors to the loyalty of visitors, the profitability of museums may rise. The next problem to be solved is how to maintain visitor loyalty. As Simpson and Seeger (2008) observe, many factors contribute to increasing or decreasing public interest in museums. Word-of- mouth promotion is a type of positive information that comes from friends and family members. This source of information is trustworthy as it displays an honest impression of tourists. Museums have an obligation to attract visitors, not only those who are wealthy or the “person most likely to be involved” (Parliament of Victoria, 1983) but also those who may be ‘loyal’ to the organization. Reimer and Kuehn (2005) show that museum visitors pay significant attention to the service environment, the service process in particular. For example, Raajpoot, Koh, and Jackson (2010) propose that in assessing a museum visit, visitors may consider physical aspects, such as the exhibitions or the building and also make a holistic evaluation. Furthermore, this impression is constructed based on quality perceived by tourists. In China’s museum industry, cultural content is important for museum projects, and the catchphrase is ‘content is king’. For instance, the Suzhou Museum provides different services for children, teenagers, the elderly, and professionals. It does not rely only on Bei Yuming’s architecture to attract tourists; museum stakeholders believe that content makes the difference in the long run. However, as visitors participate in museum tourism for different purposes, it is unknown whether emotional attachment is one of the factors that motivate visitors. By arranging tours or designing content based on emotional experience, a museum can allow the visitor to relive the past or reexperience events, enabling them to feel anticipation, shock, sadness, anger, inspiration, and peace and strength.

Thus, it seems that the relationship between quality, satisfaction, and loyalty can be identified in the museum

domain, just as in other sectors of the tourism industry. However, little evidence in the tourism context exists to show a causal relationship between loyalty and emotional attachment in the museum tourism context. The objectives of this research are: 1) to develop a model of perceived service quality, visitor satisfaction, and conative loyalty in the museum domain; 2) to emphasize the importance of emotional attachment in the model and further identify the relationship between emotional attachment, perceived quality, visitor satisfaction, and the conative loyalty of museum visitors; 3) to discuss the effects of emotional attachment and conative loyalty on the museum and its visitors, and to further reveal the role and impact of emotional communication on the cultural communication of museums, and provide empirical support for practitioners. This study focuses on the case of the Anthropology Museum of Guangxi (AMGX). AMGX is dedicated to Zhuang culture. It is a large, first-class national museum with an area of 33,000 square meters.

Currently, it holds a collection of 35,000 pieces (sets) of ancient bronze drums, national costumes, brocade embroidery, tools, folk arts and crafts, and folk houses. Six permanent exhibitions exist: Bronze Drum Culture; Colourful Guangxi-Guangxi Ethnic Culture; Zhuang Culture; Chinese Culture for Different Nationalities; Colourful World-The International Ethnic Culture Collection; and Yesterday Once More-Century Old Items. The museum is the national cultural and educational base of the government and the university and receives visitors from all over the world. As it is in Nanning, the capital of Guangxi, it is a popular choice for sightseeing.

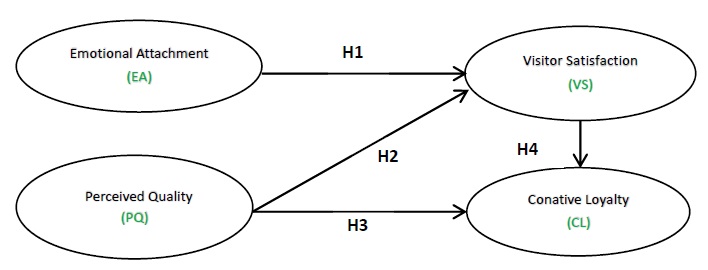

This study aims to compare the effects of emotional attachment, visitor satisfaction, and perceived quality on conative loyalty. It provides valuable managerial and academic implications for studying museum tourism because these relationships have not been previously systematically evaluated in the museum industry. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to analyze the model. Based on a review of the literature on emotional attachment (EA), perceived quality (PQ), visitor satisfaction (VS), and communicative loyalty (CL) and the relationships among these concepts, we propose the following research hypotheses and conceptual framework (Figure 1).

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Emotional attachment positively influences visitor satisfaction ( EA→VS)

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Perceived quality positively influences visitor satisfaction (PQ→VS).

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Perceived quality has a direct positive effect on conative loyalty (PQ→CL).

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Visitor satisfaction has a direct positive effect on conative loyalty (VS→CL).

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Emotional attachment has a mediating effect on the correlation between perceived quality and conative loyalty (EA→VS→CL).

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Visitor satisfaction has a mediating effect on the correlation between perceived quality and conative loyalty (PQ→VS→CL).

This study is structured as follows. First, a literature review of the four fundamental concepts, EA, VS, PQ, and CL, is presented. Second, the methodology is outlined, including the data collection procedure and PLS-SEM testing. Next, the test results are analyzed and discussed. The theoretical and managerial implications and the research limitations of this study are covered in the final section.

2. Literature review

2.1 Emotional attachment

The National September 11 Memorial and Museum (9/11 memorial museum) is famous for its emotional impact. The exhibition expresses the heartrending emotions of people in New York and across the United States. The emotional design of the 9/11 museum elicits visitors’ emotions, conveys a large amount of information, and leads them to a final sense of peace. This complete emotional design not only achieves the goal of presenting the 9/11 event as completely as possible to visitors quickly but also enables them to smoothly return to real life after the experience. As Hsieh (2010) remarks, museum practitioners should focus on push and pull motivation for stimulating visitors’ willingness to visit. To illustrate, establishing an attachment for visitors is crucial to a museum’s successful design.

The idea of attachment was first proposed by British psychiatrist John Bowlby. Until the late 1980s, research on attachment theory mostly focused on children. Attachment theory presents ideas and concepts that concern the formation, preservation, and elimination of intimate relationships among human beings (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Hazan & Shaver, 1994). However, psychological and marketing research has demonstrated that attachment can extend to many other areas, including inter- and intrapersonal relationships (Thomson and Johnson, 2006), regions or destinations (Williams & Vaske, 2003; Moore & Graefe, 1994), objectives or properties (Kleine & Baker, 2004; Ball & Tasaki, 1992), and enterprises or brands (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006; Paulssen & Fournier, 2007; Park & MacInnis, 2006). Recently, emotional attachment theory has been widely applied to the marketing sector (Thomson & Johnson, 2006). Paulssen and Fournier (2007) empirically showed that similar behavior patterns occur within business and interpersonal relationships. To discuss emotionally aroused attachment, the term “emotional attachment” was coined by Thomson (2006) and Thomson, MacInnis, and Park (2005). However, Albert, Merunka, and Valette-Florence (2008) adopted the word “love”.

Despite differences in terminology, the main findings of several studies suggest that consumers can develop solid emotional bonds in business relationships. Blackston (1992) first proposed the concept of brand relationship and believes that brand relationship is a two-way communication between the perception of a certain brand and the reflection of the brand for customers. Paulssen and Fournier (2007) observed that, in the automobile service industry, personal safety attachment promotes stronger business relationships. Albert et al. (2008) summarized 11 dimensions of love in the consumer-brand relationship. The theoretical basis of the definition of attachment is social cognition theory, particularly the self- concept theory, which regards attachment as representing the degree to which individuals develop and maintain a self- cognition structure.

The Destination Emotion Scale (DES) was developed by Hosany and Gilbert (2010) to measure the diversity and strength of visitors’ emotional experiences towards a place. In environmental psychology (e.g., Hidalgo & Hernandez 2001; Williams & Vaske 2003) and tourism literature (e.g., Lee, Kyle, & Scott 2012; Yuksel, Yuksel, & Bilim, 2010), two major types of destination emotional conceptualization dominate: emotional and functional attachment. Currently, emotional attachment is defined as the emblematic meaning of a place as an emotional repository with implications for one’s life (Giuliani & Feldman, 1993). The existence of a personal history between consumers and brands is essential for emotional attachment (Belk, 1988), and satisfaction may only come from a few consumption experiences.

2.2 Visitor satisfaction

Many customer satisfaction theories in the literature exist: anticipation-disconfirmation, absorption, comparability, absorption-comparability, fairness, achievement, comparison- level, generalized negativism, and value-recognition (Oh & Parks, 1997). The Anticipation-Disconfirmation Paradigm (ADP) is most frequently used in research on satisfaction. The ADP focuses on the perceiver’s comparison between anticipated and real experiences, which can have three results: confirmation, positive disconfirmation, or negative disconfirmation (Oliver, 1980). In the tourism context, the first and second results mean that the visitor is satisfied with the travel experience, whereas negative disconfirmation means that the visitor is unsatisfied. Although ADP is a generally accepted model, the inclusion of expectations in the satisfaction scale remains disputed. The ADP assumes that people have firm expectations before going to a destination because without prior anticipation, tourists cannot experience confirmation or disconfirmation (Yüksel & Yüksel, 2001). Brucks, Zeithaml, and Naylor (2000) argued that this hypothesis is not suitable for the travel context, as travel products are based more on experience and trust attributes than on search attributes.

While many studies involving satisfaction relate to tourism context, some scholars have also turned their attention to museums. Sulkaisi and Idris (2020) demonstrate the relationship of overall visitor satisfaction, service quality, and loyalty by applying data collected from the Adityawarman Museum. Visitors may not have many expectations of museums, as they visit them infrequently. In addition, by establishing the dimensions of service quality and using the multilevel model as the framework, Wu and Li (2015) consider Macau Museum visitors as research objects for further exploring the influence of service quality on emotions. The behavioral intention generated by the influence of comprehensive emotion and service quality on visitor satisfaction are also illustrated. Vesci, Conti, Rossato, and Castellani (2020) examined the mediating effect of satisfaction by studying the relationship between museum visitor quality of experience and WOM behavior in the Italian Museum. Siu, Zhang, Dong, and Kwan (2013) proposed the importance of new service bonds as well as its connections with customer value, which further influences the sustainable development of the museum industry.

2.3 Perceived quality

Because of rapid social and economic development, the concept of ‘quality” has continued to be enriched, improved, and widened. Quality can be defined as the degree to which an object’s the intrinsic features meet the user’s requirements. The idea of service quality has prompted extensive research, such as the application of the evaluation tool SERVQUAL, which was introduced in the 1980s (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1988). SERVQUAL evaluates five service quality levels: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy, with a set of questions for each level. Survey respondents answer each question in terms of expectations, true feelings, and minimum acceptance. Recent research shows that SERVQUAL can predict service quality and suggest development initiatives. Since its development, experts and scholars in the service and tourism industries have widely used it (Armstrong, Mok, Go, & Chan, 1997; Atilgan, Akinci, & Aksoy, 2003; Hui, Wan, & Ho, 2007; Hsieh, Lin, & Lin, 2008). Lee, Petrick, Crompton (2007) highlighted that the service quality of a group can better predict the behavioral intention of tourists than the notion of quality as simply overall advantage or superiority. Perceived quality commonly refers to consumers’ comprehensive experience of the advantages of a brand compared with comparable goods and determines the influence assessment ratio of the brand. Perceived quality is also associated with brand perception. If the original product is popular among consumers, accepting derivative products is easier for them. Consumers’ involvement and experience should be prioritized to improve product perception. For the service industry, Gronroos (1982) proposes the customer perceived service quality model to define customers’ evaluation of service quality, wherein consumers compare their authentic feelings and expectations towards a service. If expectations are satisfied, their feelings are positive, and vice versa. Gotlieb, Grewal, and Brown (1994) considered models from different causative perspectives and found that service quality can affect satisfaction level and that the latter also influences consumers/visitors’ willingness (Taylor & Baker, 1994).

2.4 Conative loyalty

Copeland was the first to introduce the notion of loyalty into tourism studies in 1923 (Sun, Chi, & Xu, 2013). However, loyalty remains a frequent subject of debate among scholars (Kim & Brown, 2012; Weaver & Lawton, 2011) and is considered a significant indicator of the prosperity of the tourism industry. A loyal attitude means that an individual wishes to keep developing a connection with a service or product supplier, whereas loyal behavior is a person’s sustained support of a place or product (Morais & Lin, 2010). In the context of museum, the relationship between the loyalty formation process and the internal and external dimensions of the physical environment are proposed by Han and Hyun (2019) in museum research and demonstrates the mediating role of museum visitors’ cognition, evaluation, and motivation factors.

Various methods can be used to define and measure loyalty (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978). Visitor loyalty is defined as the connection between a single visit and repeat visits (Dick & Basu, 1994). In recent studies, scholars have analyzed behavioral intention using a cognitive-emotional framework (e.g., Lam, Shankar, Erramilli, & Murthy, 2004; Oliver, 1999), with theoretical support based on Bagozzi’s (1992) model of the self- regulation mechanism.

George and George (2004) use “how often and how much past buying” and “willingness to travel again” as substitutes for loyalty when studying the mediating effect of attachment on destination loyalty. Kyle, Graefe, Manning, & Bacon (2004) use “the number of days spent, the number of miles traveled, and the proportion used” to replace behavioral loyalty. According to Simpson and Siquaw (2008), public praise conveying willingness is one factor in loyalty. Oliver (1999) holds that loyalty research should focus on three stages: first, a special fondness for rival brand characteristics; second, an emotional and attitudinal preference for a product; and third, greater willingness to buy the product over competing products. Initially, consumers’ loyalty to a service occurs through recognition, then involves an emotional “like” or “don’t like” response, and, finally, a conative feeling of “like” or “don’t like” (Back, 2005; Oliver, 1997). Therefore, the loyalty and commitment of tourists to a service supplier is established gradually at each loyalty stage. According to Oliver (1999), tourists can remain loyal at each stage of an attitude expedition framework comprising diverse factors. Loyalty is affected by multiple elements during different loyalty phases (Evanschitzky & Wunderlich, 2006). Buyers will be emotionally loyal to a product if they have a positive attitude toward it. Compared with cognition, emotion more deeply influences consumers and is less easily refuted (Oliver, 1997). Pedersen and Nysveen (2001) argue that behavioral loyalty cannot be completely predicted by emotional loyalty, although emotion is more powerful than cognition. Buyers pleased with a product in a service classification may have emotional loyalty to other brands in the same classification. Conative loyalty, one of the three most powerful factors, may increase behavioral loyalty more than cognition and willingness (Pedersen & Nysveen, 2001). Pedersen and Nysveen (2001) define it as consumers’ willingness to continue using the brand later.

3. Methodology

3.1 Questionnaire design

The study adopts a quantitative research method, a questionnaire, which is used to obtain results. The survey measured respondents’ demographic variables, emotional attachment attributes, perceived quality, visitor satisfaction, and conative loyalty. It focused on evaluating visitors’ experiences relative to destination loyalty. The last part of the questionnaire included questions on the background of respondents, such as income, gender, occupation, and so on.

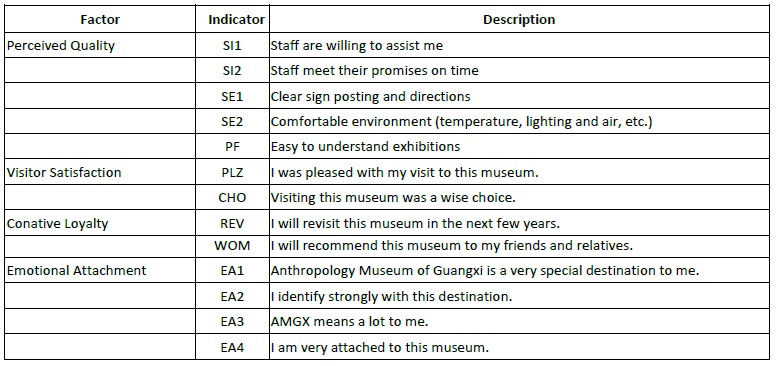

The scale items are listed in Table 3. These scales were adopted from previous studies and measured on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (the most negative rating) to 5 (the most positive). The experts from this museum verified the validity and consistency of the contents for both original English and Chinese scale visions. These researchers are fully qualified to examine both content accuracy and language proficiency. The items from the scale of Williams and Vaske (2003) were used to measure emotional attachment with some adaptation: “AMGX is a really special place to me”; “I identify very strongly with this museum”; “AMGX means a lot to me”; and “I am strongly attached to this museum.” The items used for measuring service were taken from McLean (1997) and Akama and Kieti (2002) and the items discussing the product from Phaswana- Mafuya and Haydam (2005) and Rowley (1999). Visitor satisfaction and conative loyalty were tested using other methods. Visitors’ satisfaction with the overall museum experience was measured using two items coming from Oliver (1997), which were “I was pleased with my tour of this museum” (abbreviated as PLZ) and “visiting this museum was a wise choice” (CHO). In addition, two items used to measure conative loyalty were taken from Zeithaml, Berry, and Parasuraman (1996): “I will visit this museum again in the next few years” (REV) and “I will recommend this destination to my friends and relatives” (WOM).

In the last part of the questionnaire, a categorical scale was used to record the sociodemographic characteristics and tourism-related habits of the respondents. The variables included their occupation, whether they visited the museum alone or in a group, their ethnicity, local/nonlocal residence, and so on. A pilot study was conducted using a questionnaire. The main purpose of the pilot testing was for eliminating potential problems based on a small sample (Malhotra, 2004). According to Wong and Ko (2009), reliability can be improved by a pilot study, and the appropriateness of data collection instruments can be ensured. Malhotra (2004) states that a sample of 15 to 30 cases is ideal for a pilot study. The sample size of the pilot study was 40 randomly chosen museum visitors.

3.2 Data collection

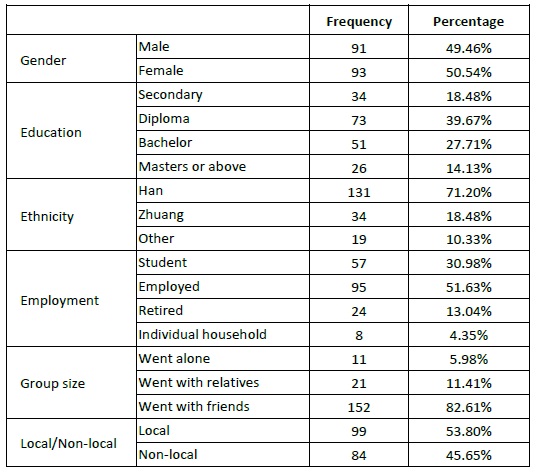

Domestic visitors (local and nonlocal) were the target group in this research. The questionnaire was applied using quota sampling at AMGX (Table 1). On November 14, 2019, 300 questionnaires were personally distributed at the exit of AMGX. A total of 184 valid questionnaires were obtained, giving an effective response rate of 61.3%. To prevent misunderstanding among the respondents, we offered on-site instruction on completing the questionnaire.

3.3 Analysis design

The research model was evaluated using the partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling technique and SPSS Statistics technique. PLS is highly appropriate for this study as it offers accurate estimates of the impact of interactions, with minimal restrictions on the size of the sample, measurement scale, and distribution of residuals.

A single factor was used to estimate the constructs, and data are often distributed abnormally (Booker & Serenko, 2007). According to Haenlein and Kaplan (2004), the variance of dependent variables can be maximized by PLS and can then be estimated by independent variables. In this study, SmartPLS 3.2 was used to test the constructs and relationships, and SPSS20.0 was used for tasting the normality distribution of variables.

4. Findings

4.1 Sample characteristics

The characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. Almost as many women (50.54%) as men (49.46%) participated in the survey. More local than nonlocal people (53.80%) were included, and the majority of respondents were in the 18-30 age group (39.13%). A total of 39.67% had a diploma or degree. The majority were of Han nationality (71.20%), and most were employed (51.63%). Most of the respondents (82.61%) visited the museum with friends. The distribution of the samples was in relative equilibrium.

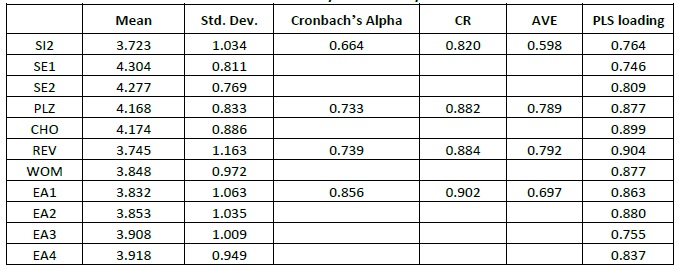

4.2 Reliability and construct validity

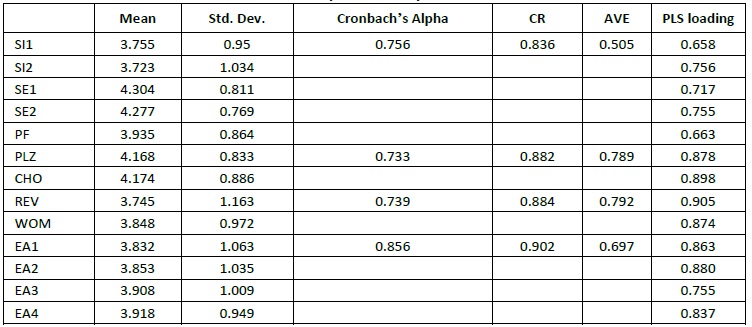

The loadings of the model by PLS are shown in Tables 2 and 3, and the construct reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) are also presented as the loadings of the measurement model. The reliability of all constructs is higher than 0.70. The

value of CR for each construct was greater than 0.80, and the value of AVE for each construct was greater than 0.50. The Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.733 to 0.856. These figures indicate that the variance in the constructs to measure error is enough (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Table 2 Reliability and validity of the constructs

Note: All loading values are significant at p < .050.

The results of PLS loadings are showed in Table 2. The value of PF and SI1 are below 0.70 and above 0.40 (PF=0.663, SI1=0.658), which should be removed from the construct of perceived quality (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2011). After removing the PF and SI1 from perceived quality, results are presented in Table 4, and the value of CR and AVE for perceived quality are both lower than before (CR=0.820, AVE=0.598). The value of Cronbach’s Alpha for perceived quality is 0.664 (smaller than 0.70), showing that the variance in the constructs is inadequate for measuring error (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).Thus, the indicators PF and SI1 can be retained in the construct (Hair et al., 2011).

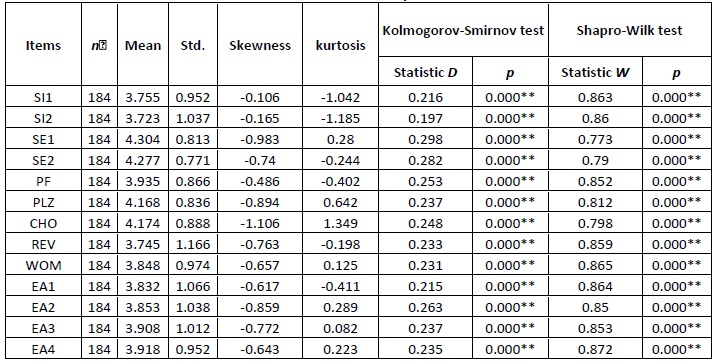

The normality test is shown in Table 5 and estimated using SPSS 20.0. The K-S test is used to evaluate the normality distribution, as the sample size is greater than 50 ( Lilliefors, 1967; Drezner & Zerom, 2010). The p values of all indicators are smaller than 0.05, indicating an abnormal distribution. However, the absolute values of skewness for all indicators are smaller than 3, and the absolute values of kurtosis of all indicators are less than 10, which is considered a normal distribution( Lilliefors, 1967; Drezner, & Zerom, 2010).

Note: * p<0.05 ** p<0.01

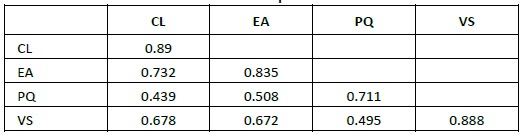

The correlation analysis is presented in Table 6. The square roots of the construct correlations are smaller than their AVEs (Gefen,

Straub, & Boudreau, 2000). This confirms the validity of the discriminant method.

4.3 Results of the PLS analysis

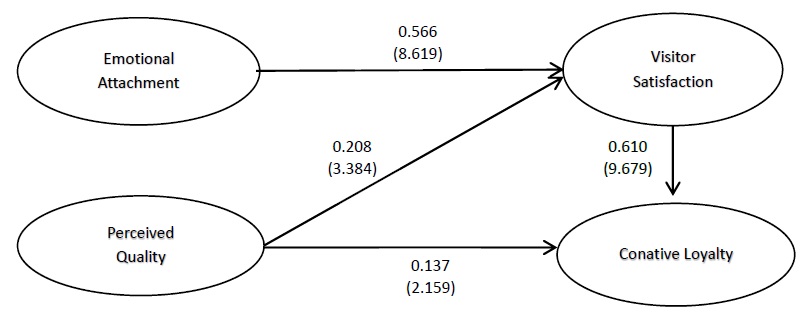

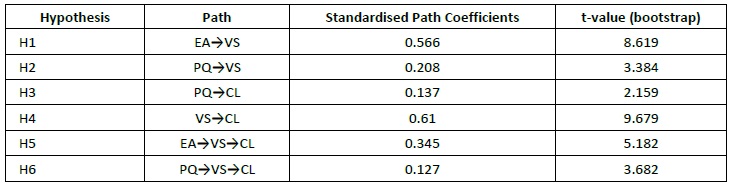

Given that there were 184 respondents, following Hair et al. (2011), 5,000 samples were used to perform bootstrapping to ensure that path coefficients were significant. The PLS results are shown in Figure 2. The R² value of the structure model was 0.474, and the adjusted value of R² was 0.468. Therefore, this is a “moderate” model (Hair et al., 2011). All three factors (perceived quality, emotional attachment, visitor satisfaction) showed a significant relationship with conative loyalty, which supports H1, H2, H3, and H4. The indirect effects of PLS are shown in Table 4. Emotional attachment and perceived quality have a significant relationship with conative loyalty, which supports H5 and H6.

Table 7 Hypothesis testing

Note: Loadings are significant at p < .05 R²(visitor satisfaction) = 0.484; R²(conative loyalty) = 0.474

The results in Table 7 and Figure 3 indicate that emotional attachment has a positive impact on visitors’ satisfaction (H1; β = 0.566; p < 0.05). Visitor satisfaction was positively affected by perceived quality (H2; β = 0.208; p < 0.05), and conative loyalty is positively affected by perceived quality (H3; β = 0.137; p < 0.05). Furthermore, visitor satisfaction positively affected conative loyalty (H4; β = 0.61; p < 0.05). Emotional attachment is a mediator variable that affects the connection between conative loyalty and perceived quality (H5:EA→VS→CL, β = 0.345; p < .05). The relationship between conative loyalty and perceived quality is affected by visitor satisfaction, which is a mediating variable (H6:PQ→VS→CL, β = 0.127; p < .05). The direct path coefficient from perceived quality to conative loyalty is 0.137. However, the indirect path coefficient is 0.127. The latter is smaller than the former, which means that the influence of perceived quality on conative loyalty is weakened by the mediator.

5. Theoretical and practical implications

Based on the results above, EA and PQ significantly affect VS, and EA, PQ, and VS are all connected to the CL. These results indicate that the better visiting experience visitors have during a museum visit, the more likely they are to become loyal customers towards the destination (Campón-Cerro, Hernandez- Mogollón, & Alves, 2016; Chi & Qu, 2008; Wu, 2016). Ultimately, the desire to revisit can be enhanced (Grappi & Montari, 2011). As the public “attention” generated by the “attraction” of museums is the source of the realization of the social value of museums, the extent to which the social value is realized is determined both by the number of visitors and by public “attention.” Attention includes public satisfaction, trust, and loyalty.

Moreover, the intangible and tangible qualities of AMGX strongly affect visitors’ choices. As Chi and Qu remark, when a person perceives products and services in a certain way, this may directly change their expectations of the associated experience (2008). Tangibility can be easily defined as the museum’s setting and human resource management. To illustrate, the measurement scale of PQ in this research converts staff’s prompt assistance, museum environment, facilities, and so forth. In contrast, the enthusiasm of museum staff and the communicative function of display can be categorized as part of an intangible aspect. Furthermore, as the museum provides material evidence related to the production, life, culture, and natural environment of local Guangxi citizens, it contains a large amount of cultural resources and a huge amount of information, which are also the source of the museum’s cultural power. However, the cultural power of museums is not static. They not only protect the physical form of culture but also activate a large amount of cultural information, thus nourishing cultural inheritance and innovation. These are significant factors influencing the perceived quality of AMGX.

This study mainly contributes by applying emotional attachment (EA) to museum tourism. The establishment of an emotional connection is based on Zhuang cultural inheritance. Visitors’ yearning, expectations, and curiosity about the culture stimulate this emotional connection. Part of what makes cultural objects so important is that they offer useful cultural lessons for the present and future. To some extent, all cultural elements, including objects, await the moment they are reused. The energy of the objects and the efforts of the collectors and custodians make the museum vibrant. Thinking and communicating behaviors, emotional attachment, and decision- making are brought together and recreated in the museum, which benefits everyone’s behavior and thinking. Laws and regulations are necessary for widen educational reform, share high-quality educational resources, and pass on traditional culture. Museums are essential in national educational reform.

6. Conclusion

The museum expresses its cultural connotations, which can combine specific cultural traditions and effective emotional expression through different forms of demonstration. Provoking positive or negative psychological resonance with the audience, such as emotional attachment, perceived quality, which directly or indirectly affects the conative function and viewing the emotions of the visitors. By employing the affective connection, which is combined with service quality and satisfaction, and to develop a research model in the context of the museum industry. For presenting a quantitative study of four constructs: emotional attachment, visitor satisfaction, perceived quality and conative loyalty, visitors (both locals and nonlocals) are involved in the data collection, and six hypotheses are positively supported. In the museum, using emotional power can uncover the hidden significance and value information of cultural relics in the collection. so that changes in the satisfaction of visitors to the museum and ultimately promote the generation and increase of visiting behavior.

7. Limitations and further studies

The limitations of this research are in the foundation for future research. First, as the survey was limited to visitors to one specific anthropology museum in the capital of Guangxi, the sample and results may not be generalizable. Furthermore, as the research focuses on one cultural museum, the results cannot be applied more generally to the field of museum tourism. Future studies on other museums could help determine whether different visitors and museum samples produce similar results. Our study also only examines three antecedent variables of conative loyalty: emotional attachment, perceived quality, and visitor satisfaction. However, many other variables can predict the behavioral intentions of consumers (museum visitors). Some researchers have tested models of the decision-making process. Examples include Tiets’ (1993) three- dimensional process (selection of product, variety of shop, and purchase point), and the TSRV formula introduced by Olach (1999). In museum tourism, the incentives/attributes of customer/visitor loyalty remain underexplored, and regional distinctions may lead to differences. Thus, these areas are worth future investigation.