Introduction

Reports and research on adult education uses the quantified measurement of hours spent by the learners (e.g., Adult Education Survey (AES), BIBB, 2012), participation rate according to average weekly working hours (Widany, Reichart, Christ, & Echarti, 2021, p. 231), or the volume of instruction hours by teaching (e.g., Eurostat, 2020a). The limitation of understanding the complexity of learning and participation through this quantitative research seems obvious. The OECD-survey (2017) could show that “too busy at work” and “childcare or family responsibilities” were the main reasons, globally, for non-participation in adult education (2017, p. 319, Table C6.2). Aspects, such as the diversity of the struggling sense of obligations (time-concurrence), the time-experiences during learning itself, and learning as a time oasis, however, remain invisible. Beyond the instrumental and quantifiable aspects of time in adult learning and education (ALE), a critical question is how to challenge deeply held assumptions limiting how (adult) education research investigates time. Therefore, the central questions pursued in this paper are: What does it mean to advocate for learning beside other affairs and time-consuming tasks of daily life? How to organize explicit timeslots for learning, for example, when taking care of children? How do this questions and issues relate to gender, gender roles and norms in our society? It is relevant to reflect on the role of adult education and how it might strengthen or even reproduce existing social gender structures and temporal regimes (Alhadeff-Jones, 2017; Schmidt-Lauff, 2012, 2019).

Time and gender are cross-cutting concepts (“mega-categories”), often universally recognised and commonly used, because they interact potently with each other as central components of our relationships with ourselves and the world. Few educational studies, however, define the terms gender and time or bring them into intersection. The terms are used as if the meanings attached to these words are universally understood. This paper first examines both “mega-categories”, bringing them under transnational, comparative reflection by analyzing the political context in the European Union (EU), exemplified by two countries (Slovenia and Hungary). As the home countries of two of the authors, we take them as familiar baselines (cf. Bray, 2005) while trying to understand their context determination related to time and gender via a triangulating methodology. What it means to take time for formal and non-formal learning through the lens of gender facets intersecting with national contexts (e.g., laws, time politics, acts) and sociodemographic factors (e.g., employability status, childcare activities, age) are underlined with quantitative data from national and EU surveys. Elaborations in interviews give voices to adult learners in Slovenia and Hungary to do justice to the multicomplex character and relational interweavement of time, gender and adult learning. After a triangular interpretation, the conclusion points out temporal constraints and the wider benefits of learning due to gender and temporal facets, such as rhythmic harmony or time oasis.

Conceptualizing Time, Temporality and Gender

Time is not only a quantity for describing physical processes (e.g., movements), but also - similar to space - a variable for reconstructing the relational constitutions of sociality and individuality. Temporal phenomena and time are central dimensions of human experience and social practice. First, time is “the part of existence that is measured in minutes, days, years, etc., or this process considered as a whole” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021, first paragraph). Aside from its measurable or quantifiable aspect, it is an abstract concept rarely thought of as formatively embedded in our everyday reality (Berger & Luckmann, 1991). The idea that the nature of time is historically variable (cf. Wendorff, 1980) and multifarious (there is no single time, but many times) opens a perspective about shaping time through sociocultural influences (Levine, 2006; Schilling & O’Neill, 2020). In parallel, time becomes a matter of individual responsibility (cf. Elias, 1984), which creates a Zeitgeist where the subjective performance of time is central. The frame of reference is a person’s lifetime, where biography is understood as a meaningful and orderly contextualisation and modalisation of an individual’s life experience (e.g., gendered time perceptions for learning; cf. Schmidt-Lauff & Hassinger, in press).

Temporal facets in adult education are woven into political norms of lifelong and lifewide learning (see Schmidt-Lauff, Schiller, & Camilloni, 2018 for an overview). In modernity, diverse time regimes unfold (Rosa, 2013), which follow the topos of dynamic, acceleration and optimisation with strong normativity for the individual and their learning. This is especially the case in learning with continuous adjustments and personal (adaptive) transitions to changes (ecological, economical, global, societal, etc.). Lifelong and lifewide learning is becoming central as “total education concerned by all the dimensions of personality, all the phases of individual existence and all the social categories” (Fourcade, 2009, cited in Alhadeff-Jones, 2017, p. 130). We suggest time is of central importance for researching participation and non-participation in learning, biographically contextualised in a historical, cultural and social-political context. Levine has stated:

how people construe the time of their lives as a world of diversity. There are drastic differences on every level: from culture to culture, city to city, and from neighbour to neighbour. And most of all, I have learned, the time on the clock only begins to tell the story. (Levine, 2006, p. 16)

Beside this diverse cultural phenomenon, we can observe a growing number of temporal communalities. Globalisation connects us in a similar perception of time worldwide, now triggered even more by digitisation (“everything, everywhere in anytime”). Globalisation breaches the limitedness of time and space and creates a common instantaneousness as a core of a globally established temporal system. Significant transformation and fast-paced worldwide dynamics are affecting social, individual and technical acceleration (Rosa, 2013). Effects on ALE are driven by infinite (lifelong) transformations, which focus less on continuous maturation, and more on quick adaptations. Schmidt-Lauff (2012, 2019) has outlined several theorems critically regarding the connection between time and learning in educational science: all learning occurs in time, learning is always acting in time, time is a resource, explicit time for learning in adulthood is rare and not a matter of course, time is of great symbolic significance, habituation of time through education and the agenda of lifelong learning set temporal norms.

From the perspective of a participant, temporality is an important aspect of one’s life as it affects one’s existence and life experience and the experience of learning. Temporality is even more pertinent when the participant is female. (Data have shown how differently, by gender, adults spend their time in care, domestic work and social activities; cf. European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020a, 2020b). The third goal of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals, established in 2000, was to eliminate gender disparity in education and lifelong learning. The sustainable development goals (SDGs) highlight the need to ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed “through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality” (United Nations, 2017).

Gender, understood here as a culturally constructed category, is neither fixed nor the causal result of sex, which, in contrast, is biologically predetermined (Butler, 1990, p. 6). As West and Fenstermaker (1995) describe, gender is not only a characteristic constructed by an individual, “it is a mechanism whereby situated social action contributes to the reproduction of social structure” (West & Fenstermaker, 1995, p. 21). Concerning the time spent on household work, Berk assumes “gender” as one of two “production processes” (the other includes household goods and services) that individuals “do simultaneously” (Berk cited in West & Zimmerman, 1987, p. 143). Important for our temporal view, Berk’s paradigm is the simultaneity within gender activities:

Simultaneously, members ‘do’ gender, as they ‘do’ housework and childcare, and what (has); been called the division of labour provides for the joint production of household labour and gender; it is the mechanism by which both the material and symbolic products of the household are realised. (Berk cited in West & Zimmerman, 1987, p. 144)

In other words, taking care of the household is not about some members having more time available than others, more skills for that job or more power but about the gendered determinations that pre-define how family members dedicate their time to household work or employment.

Since its first edition in 2013, the European Gender Equality Index (EIGE) has tracked and reported progress by providing a comprehensive measure of gender equality, tailored to fit the EU’s policy goals. The index reveals both progress and setbacks, and explores what can be improved to seize opportunities for change, for example, “Far more women than men also work part-time (8.9 million versus 560,000) owing to their care responsibilities” (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020a, p. 13). The index continues to show the diverse realities that different groups of women and men face, and examines how elements such as disability, age, level of education, country of birth and family type intersect with gender to create different pathways in people’s lives. For our investigation, the domain of time (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020a, p. 12 & pp. 44 ff.) is important although, in EIGE, individual learning is not included as a criterion:

(…) to persistent gender inequalities not only in relation to informal care for family members but also in terms of access to leisure time and activities. Increasing time pressures from both paid and unpaid work, combined with gender norms and financial constraints, limit access to leisure for many groups of women, which can have ramifications for their overall well-being and even their health. (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020a, p. 12)

Methodology

The comparative context of this study is based on a multilevel comparative analysis (cf. Field, Künzel, & Schemmann, 2016; Reischmann, 2021; Slowey, 2016; Sweeting, 2014). Looking at the subject in relation to the macro-, meso- and micro-level of analysis (Lima & Guimarães, 2011) enables insights into national contexts, policy legislations and individual situations. Comparative adult education research offers a transcultural approach with the idea of “analytical comparison” (Egetenmeyer, 2014) for revealing “social-cultural interrelations” (Schriewer, 1994, cited in Egetenmeyer, 2014, p. 16). This provides greater potential to understand gender, time and temporal aspects in relation to (non-)participation in ALE. Time and gender seem suited to the “mental application of comparison” (Jackson, 2014 ; Sweeting, 2014, p. 168).

Time and temporal phenomenon are driving forces behind social-cultural structures (cf. Jokila, Kallo, & Rinne, 2015), historical specificities (cf. Sweeting, 2014) or biographical analyses (cf. Schmidt-Lauff & Hassinger, in press). First, time as a transcultural (global) category is under comparative reflection in two European countries (Slovenia and Hungary). Second, focused temporal phenomena (hours of learning time; (learning-)time legislations) are working as comparative indices, as pieces of circumstantial evidence and purposes to understand the (transcultural) effects of time in our learning society and accelerative, temporal-disciplined modernity.

Selecting time as an important theme for comparative research is not new: “The importance of evolutionary time was emphasised in comparative research at the early stage of the development of comparative education research” (Jokila et al., 2015, p. 18). Unlike a broad, temporal-sensitive comparison, however, this early stage “focused extensively on historical analysis as a way to understand factors influencing educational systems” (Jokila et al., 2015, p. 18). Even the latest discourses about “comparing times” (Sweeting, 2014) show that time has not become a broader principle concern for comparative analyses.1 Beside the most common historical approaches (diachronic or synchronic or hybrid; Sweeting, 2014, p. 181f.), our study aims to go further and create (joint) explanations about time as a socially and individually constructed phenomenon influencing participation in multiple ways. It aims to explore the way time is represented and experienced within a certain phase of life and time (during and beyond the pandemic COVID-19)2 in two countries (Slovenia and Hungary) through narratives from 11 interviewees. This approach serves “the purpose of challenging and/or revealing unthinking prejudices, and therefore is to be welcomed as a healthy reminder (…) of female exploitation for situations in which gender (and temporality) was not the main issue” (Sweeting, 2014, p. 176). Our interviews were carried out with a half-structured questionnaire, giving the opportunity to attune questions to national realities (e.g., interviews were carried out in the local languages of Slovene and Hungarian) and individualised for the interviewees (e.g., life phase, age). From December 2020 to July 2021, 11 interviews were realised. This article focuses on the most intriguing answers and findings from the interviews, supporting or further explaining the analysis of statistical data (European and national) and legislation (Acts) in the respective countries.

Our comparative approach was first a descriptive juxtaposition between two European countries: Slovenia and Hungary (cf. Egetenmeyer, 2014; Field et al., 2016, Reischmann & Bron, 2008). Since “such juxtaposition is only the prerequisite for comparison” (Charters & Hilton, 1989, p. 3), the next stage attempted to identify similarities, differences and commonalities inbetween the two aspects (gender and time), their interrelation and contextualisation by country. Data from the Eurostat Survey on sociodemographics, (non-)participation, time (hours spent for learning) were analysed in relation to the allocation of time between males and females (drawing on statistical national data in both countries), over the years and in Slovenia and Hungary. Two European policy documents (Memorandum on Lifelong Learning (Commission οf the European Communities, 2000) and Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (Council of the European Union, 2018/C 189/01) were checked from the perspective of time and gender as macro-base.

The next analytical stage of our comparison attempted to understand why the temporal, gender differences and similarities occur and “what their significance is for adult education in the countries under examination” (Charters & Hilton, 1989, p. 3). To reach this stage of interpretative comparison we included interviews to enrich the quantitative analyses described above with a qualitative approach to understanding individual experiences and the constraints of time and gender. The qualitative interviews were carried out as half-structured interviews (cf. Flick, 1997) among Slovenian and Hungarian adults who participated in some ways in adult non-formal education. This qualitative data goes beyond statistical descriptions to better understand subjective experience and to raise awareness on time sensitivity for learning in several life phases (see sample description in Table 6). We interviewed 11 adult learners: three in Slovenia and eight in Hungary and created memorial transcripts (“selective protocol”, cf. Mayring, 2002). The difference in the number of interviewed persons can be disregarded here, since a one to one comparative juxtaposition was no longer our aim. We were making an interpretative reconstruction of temporal and gender aspects: The material we gained from the interviews offers access to collective temporalities (e.g., time regimes, such as acceleration), social patterns of time for learning (e.g., during the same life phase but different between men and women) and individual modalisation of time perception (e.g., learning time between stress and contemplation).

Comparing gender facets and temporal constraints in adult learning and participation

In comparative research targeting participation in adult learning in two countries on the macro level, it is inevitable to mention that both countries are member states of the EU. In a short descriptive analysis, we choose two European policy recommendations to check under the perspective of time and gender. The policy recommendations provided by the EU offer several conclusions on trends and on contradictions of policy and practice unfolding in qualitative interviews (see Chapter ‘Learners’ perspective - individual reflections by interviewees’). Thorough investigation offers insight and highlights and reveals the lack of discussion on temporal aspects and the hiatus of considering time constraints in policymaking for ALE. In highly accelerated, contemporary societies, time represents one of the desired elements that also affects adult education, which that has been the focus of EU policies for some years. Raising participation in adult education is one priority in recent European documents. However, temporal aspects of participation in adult education are mostly connected to employment rather than non-job-related learning and are, therefore, marginalised in their multiple relevance for the individual learner:

The Memorandum on Lifelong Learning (Commission οf the European Communities, 2000) is related to encouraging investment in human resources and discusses time-related questions for employees, encouraging employers to give employees time for the pursuit of learning (Commission οf the European Communities, 2000, p. 12) and opening a question about more “flexible working arrangements that make participation in learning practically feasible” (Commission οf the European Communities, 2000, p. 12). The memorandum also acknowledges that “personal investment in time and money” is an issue to be considered in the frame of lifelong learning with motivation, expectations and satisfaction (Commission οf the European Communities, 2000, p. 32). The issue is connected with working arrangements and provision of childcare. However, it does not consider issues connected with gender nor discusses the gender time gap.

Another European document is the Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (Council of the European Union, 2018/C 189/01). The recommendation states the right “to timely and tailor-made assistance to improve employment or self-employment prospects, to training and re-qualification, to continued education and to support for job search” (Council of the European Union, 2018, p. 7). The document emphasises the importance of contributing to building the greater society of the EU and realising the vision of the European Education Area “to harness the full potential of education and culture (…) to experience European identity in all its diversity” (Council of the European Union, 2018, p. 10). However, the document does not refer to an amount of time needed for adult learners to acquire all these competencies, nor does it reflect the need to support adult learners’ participation in continuing education to prepare them for strengthening Europe’s resilience in a time of rapid and profound change. These policy documents are characterised by a lack of temporal aspects.

National background

Slovenia is a Central European country, neighbouring Austria to the north, Italy to the west, Croatia to the south and east and Hungary to the northeast. With 20,273 km² of territory, the country is rather small and located in an intersection of different geographical regions, the Alps, the Dinarides, the Pannonian Plain and the Mediterranean (Eurydice, 2021). The country gained its sovereignty from Yugoslavia in 1991 and joined the EU in 2004. The country has around 2.1 million inhabitants with an average age of 43.7 years. In this population, 15.1% are under 14 years old and 20.7% are over 65. The rest of the population, 64.3%, is aged between 15 and 64 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2021). Data on the level of education in 20203 show that among the adults aged 15 or over (1,780,059 people; 888,426 men and 891,633 women) 22.7% finished lower secondary education or less, 52.8% completed upper secondary education and 24.5% completed tertiary education (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2020). Table 1 shows data for education levels attained, divided by gender.

Table 1 : Attained level of education of the population aged 15 or over by gender in Slovenia (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2020)

| Attained level of education | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Lower secondary education | 26.8% | 18.6% |

| Upper secondary education | 44.7% | 61.0% |

| Tertiary education | 28.6% | 20.4% |

The unemployment rate in Slovenia among the active population aged 15 years or older was 4.5% in 2020 and 51.2% were employed. The other 44.3% of the population was “inactive”4 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2020). One of the reasons for the low unemployment rate in Slovenia - compared to the average rate of 7.3% in June 2021 (cf. Eurostat, 2021) - is the high rate of participation in education and training of the youth aged 15 to 24 years. More data show (without the table) 74.3% of pupils and students in the mentioned age group were participating in education or training, which is the highest share in the EU.5

Hungary, the other selected Central European country, lies in the Carpathian Basin with border countries in the south of Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia, neighbouring Austria from the west, Slovakia from the north, Ukraine from northeast and Romania from the east. The country has a territory of 93,000 km. It is divided by two rivers, the Danube and the Theis, into two main regions geographically: Western (Transdanubia region) and Eastern Hungary (Great Pannonian Plain). Hungary also joined the EU in 2004. The country has around 9.7 million inhabitants with an average age of 42.4 years (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2021).

Based on the data for Hungary, adults aged 25 or above in 2018, 22.6% completed their lower secondary education, 46.8% upper secondary education and 23.5% tertiary education (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2021).

Table 2: Attained level of education of the population aged 25 or over by gender in Hungary (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2021)

| Attained level of education | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Lower secondary education | 16.4% | 13.7% |

| Upper secondary education | 83.6% | 86.3% |

| Tertiary education | 30.3% | 21.6% |

Adult education, policies, legislations and organisations (programmes)

In Slovenia the field of adult education is under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport. Since 2018, the Adult Education Act represents the national, central legislation on adult education in Slovenia. By this law, adult learners are defined as “persons who finished obligatory primary school wanting to obtain, update, broaden and deepen their knowledge”, and persons who finished primary school with lower educational standards or have not finished primary school and are at least 15 years old (Adult Education Act, 2018, Article 2).

Adult education in Slovenia is offered in various types of organisations. There are organisations specialised in the field and others that offer adult education programmes as one of their activities but it is not their main or primary focus. Some offer formal educational programmes for adults and others, non-formal. According to the data of the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education (2020), most of the programmes offered are in non-formal education for adults (70% of programmes in their database in the school year of 2019/2020). Among the organisations offering adult education are educational institutions providing formal education on various levels, including folk high schools, third-age universities, educational centres in business companies, chambers, institutes, associations, privately owned educational institutions, non-profit organisations, and libraries (Slovenian Institute for Adult Education, 2020).

The structure of educational institutions in Hungary has been going through fundamental changes since 2010. The tasks and responsibilities of various educational fields and levels of education are divided among the Ministry of Human Resources (e.g., public education) and the Ministry of Innovation and Technology, for example, vocational education and training, and higher education. Until 2018, the Ministry of National Economy was responsible for initial vocational and adult education and training, however, since 2018, the Ministry of Innovation and Technology has been surveying and managing this area of education. Professional and political management tasks are carried out by the state secretary for employment. The governance, organisation, maintenance and financing of education and training are appointed by sectoral laws: The Act on Public Education (Act CXC of 2011), the Act on Higher Education (Act CCIV of 2011), the Act on Vocational Training (Act CLXXXVII of 2011), and the Act on Adult and Continuing Education (Act LXXVII of 2013). The head of the vocational education and training centres (VETs) is the Minister of National Economy (from May 2018, the Minister of Innovation and Technology). The mission of this head is to develop strategic issues, prepare legislation on VETs, plan the budget for the centres and prepare the appointment of the director-general. Medium level maintenance powers related to the VET centres are provided by the National Agency for Vocational Training and Adult Education under the 2016 Act on Vocational Training, and the 2020 new concept.

Work-related learning employers support adult learning financially and temporally with employees pursuing formal education, for example, BA or MA studies or vocational training or continuing adult education and receiving paid educational leave. According to Hungarian Labour Law (2013 Act), educational leave is five days annually for employees. The employee has the right to take educational leave when preparing for or taking exams during any study programme they pursue.

In Hungary, adult and continuing education is available in formal and non-formal provision. Providers’ profiles rarely focus on one specific educational field. They tend to offer a wide range of courses and training. Regarding the structure of adult education programmes offered both in formal and in non-formal provision, Hungarian adult learners are more likely to engage in formal training that offer a certificate in the register “OKJ” (State Vocational Training Register). From an organisational aspect, adult education providers are both profit and non-profit organisations, many are foundations or associations and NGOs have also played an important role in adult education since the beginning of the 1990s in Hungary.

Time-policies affecting participation in adult education

Educational leave in Slovenia is not defined by the policies in education but by the Employment Relationships Act (2013). With this act, employees have the right and duty to continuous education and training for job-related needs and for their own interest. In both cases, Article 171 (the right to absence from work due to education) states that the employee has the right to educational leave for preparing or taking exams (Employment Relationships Act, 2013, §171). Further details can be decided upon the collective contract (contract of employment or educational contract) or “the employee has the right to absence on days when first taking the exams” (Employment Relationships Act, 2013, §171). The law does legitimate a paid exemption, but does not define this any further. As a result, there is space for individual interpretations of the paid exemption (employer, supervisor), depending on his or her values and various experiences and practices. When employees are involved in “job-related education” that might be in the interest of the employer, the chance for an employee to be eligible for educational leave might increase. The law does not state any rights for paid or unpaid leave when the employee is involved in non-formal education that is not job related or not in the interest of the employer.

Parental leave is defined in Slovenia by the Parental Protection and Family Benefits Act (2014). Parental leave is divided into three types of leave: maternal leave, paternal leave and parental leave (ibid). Maternal leave lasts 105 days, starting 28 days before the estimated date of birth. Paternal leave lasts for 30 days and cannot be transferred (Parental Protection and Family Benefits Act, 2014). Parental leave lasts for 260 days and can be used for up to 130 days by each parent, however, the father can transfer 130 days of leave to the mother, but the mother can only transfer 100 days to the father and 30 days of her leave cannot be transferred (Parental Protection and Family Benefits Act, 2014). The compensation of salary is 100% when a person is using full-time leave.

Regulation of educational leave in Hungary falls under the Labour Law (2013 Act), stating that employees have the right to education and training. It legitimates and supports job-related learning, defining the right to be absent from work due to continuing education of approximately five days per year. Employees can also benefit from various opportunities offered by the employer to pursue work-related training (mostly company-based). In the praxis of organisational training and courses, employees have no time limit or days annually to take part in internal training organised by the employer.

In Hungary, parents are provided with different kinds of parental leave as per the family protection Act (1998):

maternity leave for a maximum of 168 days following the birth. Maximum maternity leave is 24 weeks, four of which may be taken before the calculated date of birth. Mothers are entitled to infant care allowance for the period of their maternity leave. This infant care allowance is equal to 70% of the average daily pay in the period specified in the Act.

Parental leave is transferable, which means it is available for the mother or the father of the child from the date of birth to the third birthday of the child. This offers the opportunity to parents (mother or father) to pursue adult educational activities. However, there is no data available on parents’ participation rate in adult education.

Participation rates in relation to temporal and gender aspects

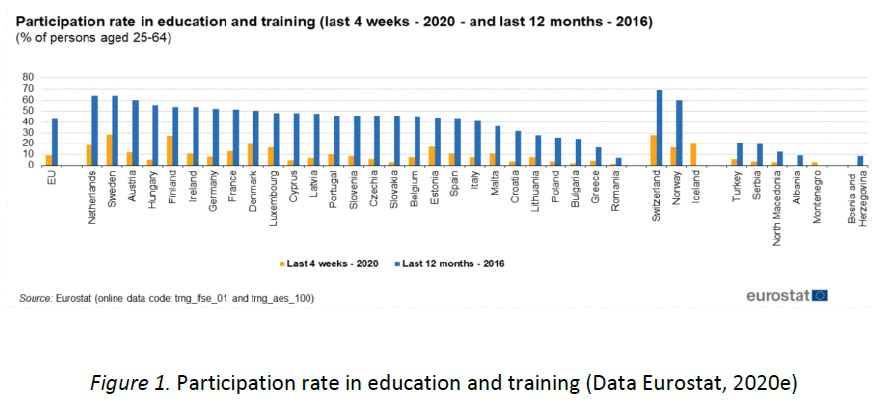

The Eurostat Survey collects data on participation in adult learning (Figure 1). This section of descriptive and analytical juxtaposition uses the latest Eurostat data, revealing comparative findings about participation rates in education and training. We have additionally extracted data from Eurostat 2007, 2011 and 2016 on gender and time, showing their relations and influences on participation. We can deduce “instruction hours spent by participant” (Table 3), distribution of non-formal education by sex (Table 4), and temporal trends over recent years (2011-2016; 2019-2020):

Participation rates in education and training, in 2016, in Slovenia and Hungary, measured over the last 12 months, were above the EU average, as seen in Figure 1. Slovenia was a little below 50% and Hungary a little above 50% of the population, aged 25 to 64 years. These data show adult education is well established in both countries, however, it is still behind some other European countries.

How much time (hours per year) do adults spend on learning?

The measurable time spent attending formal and non-formal education activities, represents an “investment” in the individual’s performance. It can be a “skill development” for both the employer and the individual (OECD, 2017, p. 367), or a “personal development” following the humanistic idea of Bildung (learning to be, learning to live together etc.; cf. European Lifelong Learning Indicators - ELLI, 2010).

Table 3: Mean instruction hours (per year) spent by participant in education and training among adults between 25 and 64 years old (Eurostat, 2020a; own illustration)

| 2007 | 2011 | 2016 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal or non-formal education | formal | non- formal | formal | non- formal | formal | non- formal | |

| European Union (28 countries) | 366 | 73 | 396 | 81 | 398 | 77 | |

| Hungary | 486 | 111 | 206 | 47 | 322 | 54 | |

| Slovenia | 317 | 49 | 470 | 63 | 375 | 142 | |

Table 3 shows that the number of hours spent in education and training is much higher in formal than non-formal education across the EU average and in both countries. However, the mean hours spent in non-formal learning varied extensively during the different survey years. Reading further into the data, the numbers of instruction hours varied across different age groups with the highest number of hours spent in formal education in the age group of 25 to 34 years and the lowest in the group 55 to 64 years (without the table). According to the data (Eurostat, 2020c), the participation rate in adult education in Slovenia was above the EU average in 2007 and 2016 and below the EU average in 2011. Participation is highly connected with educational attainment. It has been significantly higher among those with higher educational attainment level, especially those with finished tertiary education (ISCED 5-8) and, simultaneously, the share of those with the lowest attained education has been lower in Slovenia than the EU average (Eurostat, 2020c, 2020d).

The time spent on adult education and learning by adults both in Slovenia and Hungary was over 300 hours in formal education as was also the case for the EU average (Eurostat, 2020a). It is interesting that adults in both countries spent less time in formal education than the EU average in 2016, according to the latest data (Table 3). Hungarian adults spent considerably less time (almost 1/6) in non-formal education than formal, which is below the EU average and, in Slovenia, the ratio between participation in formal and non-formal education was more balanced with less than 1/3 hours spent in formal education. However, the situation in 2007 was quite the opposite, where Hungarian adults spent 120 hours more in formal education than the EU average and 38 hours more in non-formal education and Slovenian adults spent 49 less than the EU average in formal education and 24 hours less than the EU average in non-formal.

One interim conclusion can be that the policies in adult education and orientation encouraging formal and non-formal education for adults have changed in both countries in the last 15 years (see previous subchapter ‘Time-policies affecting participation in adult education’). This is evident, for example, when policies get split (the separation of the Adult Education Act from the Parental Responsibilities Act), or, policies on formal adult education, become part of other laws regulating primary, secondary or higher education (see previous subchapter ‘Time-policies affecting participation in adult education’).

How does gender affect participation in adults’ learning?

In Slovenia, males dedicate more time to non-formal education that is job related than women (Eurostat, 2020b). Table 4 shows males in Europe in 2011 and 2016 participated in job-related non-formal adult education more often than females. This statistic is especially high in 2016 in Hungary (80.9% men were in job-related training). However, the differences in Slovenia have decreased from 2011 to 2016. Females in Slovenia were participating at a higher percentage in job-related non-formal education in 2016 than 2011. The percentage increased to 13.4% and in contrast decreased to 24.6% for Hungary.

Table 4: Distribution of non-formal education and training activities of adults between 25 and 64 years by gender (Eurostat, 2020b)

| 2011 | 2016 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-formal education job or not job related | Job related | Not job related | Job related | Not job related | ||||

| Sex | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females |

| European Union (28 countries) | 84.8 | 75.5 | 14.5 | 24.0 | 83.7 | 75.3 | 14.5 | 22.9 |

| Hungary | 87.8 | 79.1 | 12.2 | 20.9 | 56.7 | 54.5 | 20.2 | 20.7 |

| Slovenia | 75.2 | 63.9 | 24.8 | 36.1 | 80.9 | 77.3 | 19.1 | 22.7 |

According to more detailed data from the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE, 2020) overall, gender equality in Slovenia, with 67.7 points, was just below the EU average, which is 67.9 points (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020a). By using time as a core domain, the EU-Gender Index is especially worthwhile for our inquiry on a time-gap in ALE. Time as an item is measuring “gender inequalities in allocation of time spent doing care and domestic work and social activities” (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020a, 2020b). Hungary, with 53.3 points, was ranking below, and Slovenia, with 72.0 points, was ranking above the EU average, which is 65.7 points (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020a, 2020b).

Table 5: Time spent doing care and domestic work and social activities by gender in Slovenia and Hungary (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020c)

| Country | Gender | “People caring for and educating their children or grandchildren, elderly or people with disabilities, every day” (%) | “People doing cooking and/or housework, every day” (%) | “Workers doing sporting, cultural or leisure activities outside of their home, at least daily or several times a week” (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hungary | Female | 30.1 | 55.8 | 16.6 | Male | 24.5 | 13.8 | 12.5 |

| Slovenia | Female | 35.2 | 81.0 | 41.4 | Male | 27.5 | 27.5 | 42.7 |

Table 5 indicates for Hungary on the aspects of family care and education, domestic work and leisure activities that women spend over 40% of their time on domestic work, which is a substantial difference in household responsibilities compared to that of men. Another drawback for women’s time management is the time spent on caring for children and family members on which they spend 5.6% more time than men. Interestingly, Hungarian women spend over 4% more on sporting, cultural and leisure activities than men. Table 5 shows that women in Slovenia spend almost 7.7% more time on care than men and 1.3% less time for leisure activities. However, the biggest gap is in time spent on housework, where the gap is over 53.5%. These differences in dividing time for different activities can also be connected to time spent in education. From the learners’ perspective, this division of time and inequalities might represent obstacles and positive benefits for women to participate in adult education.

The gender inequalities within time spent are showing a gap, which needs to be taken into consideration by adult learning organisations, providers and programme planners. These inequalities also need to be addressed on the level of policy to recognise them and find new solutions for addressing the issue. If women spend more time on domestic activities, this can affect their potential for participating in adult education. The interviews (see Chapter 5) showed it is also important to stress a personal biography and habit, according to the life stage a person is in. It is stereotyping that, for example, women with children might face difficulties finding time between employment, domestic work and childcare to participate in ALE. This time (as individually experienced temporal threshold) might have various positive aspects for the women, as demonstrated in the interviews.

Learners’ perspective - individual reflections by interviewees

After the abovementioned descriptive juxtaposition of comparison of quantitative data, the next step is to deepen gender and time-related aspects of participation in ALE. Eleven half-structured interviews (see Chapter ‘Methodology’ for methodological reflections) were carried out to understand better individual-subjective motivations to take time for learning (see next subchapter ‘Motivation to decide on learning and take time for participation’) and the experiences of different qualities of time during learning (see next subchapter ‘Experiencing different qualities of time during learning’). All answers were interpreted in relation to the interviewees different life-stages, ages, marital status, and childcare (see Table 6).

Table 6: Sociodemographic data of the Slovenian and Hungarian interviewees (n=11)6

| Interviewee | Ana | Beti | Eva | Fiona | Jonas | Karl | Lina | Maria | Otto | Peter | Sara |

| Country (Slovenia/ Hungary) | SLO | SLO | SLO | HU | HU | HU | HU | HU | HU | HU | HU |

| Age | 36 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 33 | 35 | 36 | 39 | 44 | 49 | 58 |

| Gender | female | female | female | female | male | male | female | female | male | male | female |

| Marital status (married, single, partnership) | partner-ship | partner-ship | single | single | partner-ship | partner-ship | married | married | divorced | divorced | married |

| Children under 14 in the same household | yes | no | no | no | no | yes | no | yes | yes | no | no |

| Family members in need of care in the household | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | yes |

| Employment status (employed, unemployed housewife/-man, retired etc.) | empl. | unemp. (just finished univers.) | stud. | empl. | unemp. | empl. | empl. | parent. leave | empl. | self- empl. | empl. |

| Highest level of education (based on International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011) | ISCED level 7 | ISCED level 7 | ISCED level 6 | ISCED level 6 | ISCED level 5 | ISCED level 7 | ISCED level 7 | ISCED level 7 | ISCED level 6 | ISCED level 7 | ISCED level 7 |

Motivation to decide on learning and take time for participation

Interviewees confessed reasons that had motivated them to engage in learning in their adult life. In four Hungarian cases, the motivation for participation was knowledge and skills development in work-related contexts (e.g., communication, languages, conflict resolution, personal development and competencies) for better job prospects and employment chances. Fiona also mentioned “new prospects and more chances abroad” as one of the most important reasons to start learning a language (German), which she already had experience with in early childhood, but had failed the exams. She reflects on this:

Retaking German lessons is not only a new language, but also a challenge for me, as I am more conscious of my goals and don’t get distracted or give up that easily as I remember I did as a child or as a teenager.

Two interviewees stated they were motivated by a difficult life crisis to search for “new directions, new perspectives”. Oto emphasised,

After my divorce, it was kind of a healing for me to go to this community, regularly turning my attention to something new that I have always wanted to learn (musical programming) and engage in new activities connected to music … also, just for the sake of learning something new, to develop myself as a person, as it seemed a good idea to face new challenges for personal growth.

Sara also points out biographical and social aspects (here, as a family member): “I keep myself fit with learning something new from time to time. And not just learning for the sake of a new interest, but also to be useful and learn something I can share in the family.” Belonging and being together (synchron) with a group of people sharing the same interest, is a reason, too, to participate.

The same picture of motivation can be found in the Slovenian interviews. The interviewees talked about various factors motivating them to participate in adult education, often connected to work but also to their personal future, gaining new knowledge, skills development, new experiences and insights, and meeting new people. Eva explained her motivation this way:

I mostly participate in non-formal education because I want to gain certain knowledge, information or skills. I also like meeting new people and different ways of thinking, functioning. New experiences are also important to me.

Different from the Hungarian Interviewees, one interviewee explicitly mentioned reasons connected to (future) employment aspects. However, Eva states she has been attending activities carried out by the university career centre, therefore, we can assume her learning motivation was connected to work-related aspirations.

Where possible, we added a question (see Chapter ‘Methodology’) and asked interviewees about their participation in adult education timewise. Due to different biographical life phases, they emphasised lack of time that would ensure meeting their wishes and needs in this area of their lives. Ana, for example, stated: “I have been participating in different courses when I didn’t have full-time employment, when I was self-employed and I scheduled my own working day.”

Not enough time for learning became visible as an important issue in the interviews, but, differing from the quantitative data, it was connected to different opportunities of self-organising timeslots for learning, for example, depending on family situation or employment settings. Employment status affected ALE (see Chapter ‘Comparing gender facets and temporal constraints in adult learning and participation’). Being self-employed could allow more flexibility compared to fixed working hours in regular employment. The answers revealed a connection between employment status and participation in education, even though it might bring other challenges (e.g., financial resources) that were not discussed in the interviews.

According to the interviews carried out in Hungary, the most significant difficulties that Hungarian adult learners faced, were related to general, global time dynamics of acceleration. The interviewees talked about temporal accelerative factors in every life sphere and named them as “speeding time” (Maria, Oto). One interviewee said: “adhering to the constant stress and pressure is very tiring!” (Lina). Slovenian interviewees too, confirmed time as a scarce resource, always experiencing the “lack of time” (Peter, Sara). Adult learners wished for less pressure from “work,” “colleagues”, “job-related tasks”, “stress from children’s school issues”, “driving the car in the rush hours”, and sometimes even “from family members”. They also wished for more time to relax. Beti mentioned a very time-resilient aspect: “As newly unemployed, I plan to dedicate most of my time to non-formal education before I start a new job.”

Instead of struggling with her “new” situation, the interviewee’s perception of time while being unemployed, gave her freedom. She talked about having more time that she would like to use for learning. However, this might be true only for part of the population, especially for those who do not struggle to find employment quickly. Beti has finished her tertiary education, therefore, her dedication of time while searching for a job might differ from someone with a family.

Beside employment status, family life and time spent undertaking care and domestic work and social activities could be other factors influencing the participation of adults in non-formal education. Ana, who has children, stated that she “did not have time for non-formal education in the last year when her family greeted the fourth member”. However, this was not the only reason, as she explained: “I could have found help (with babysitting) in my surroundings, but I just cannot find motivation for continuing education.” We can see two reasons for her temporary non-participation. First was care of a young child and second, lack of motivation and maybe tiredness and having no time-slot free to learn. The gap and perception of roles of females and males in the household and childcare is also present in the words of Eva who does not have children: “If I had a family, I probably wouldn’t take part in the additional courses.” As previously mentioned, this evidences the need to pay attention to the topic of time sensitivity and potential gender gaps caused by time, but based on traditional gender roles (Berk 1985, cited in West & Zimmerman, 1987, p. 144).

The biographical aspect to time and learning (“Self-relationship of biographicality”, cf. Schmidt-Lauff, 2012) brings certain constraints to when an individual can take time for their learning. Beside the (un)employment and household or family indicators, there can also be other indicators connected to individual biography (e.g., specific time of the year that a person has more time to dedicate to non-formal education). Beti has been involved in adult non-formal education as a student in some months more than in others: “On average I dedicate perhaps three hours per month. In some months more intensively, also up to six hours per day for one, two or three weeks, other times nothing.”

This is likely to be connected with the academic calendar (as Beti was a full-time student), which leaves participation to the times when a person can take more time for involvement in adult education (e.g., during the university vacation period).

Experiencing different qualities of time during learning

Ana and Beti experienced time for learning as a qualitatively multiple time. Depending on the framing context, the experienced time during learning could be positively enriching: “When I have the possibility that I’m not facing any deadlines like exams or term papers, I experience this as relaxing” (Ana). Also, “On the contrary, kind of particularly stressful (e.g., by confronting me with several tasks in parallel, I sometimes feel an obligation, similarly as in formal education”. Both examples show the diversity of time during her learning itself (“unburdened learning time” may provide a sense of “time oasis”; cf. Schmidt-Lauff & Bergamini, 2017, p. 157), and as a side effect or companion effect, the struggling sense of obligation (e.g., by organising timeslots for learning beside family, work, care activities). Nevertheless, Ana conclusion in the interview is a second common temporal facet: “In both cases time flies fast when I’m learning!”. Also, Beti stated: “In most cases time flies fast in non-formal learning for me. I’m experiencing feelings of contentment. Especially when I’m learning something that is quite in contrast to what I’ve been studying.”

These interview statements also emphasise the importance but difference in the study of non-job-related topics, which may be fostered and enhanced for different (positive, leisure) time qualities. Learning as a space for wider temporal benefits becomes visible here: “Adult education and learning might be able to generate learning as a counterpart to or against acceleration. This generates perspectives distanced from the general meaning of using time ‘efficiently’” (Schmidt-Lauff, 2019, p. 12). Eva pointed out feelings of stress, anger, frustration and resignation when lacking time or when time was not used effectively. These can all have quite the opposite effect to the abovementioned “time oasis”. A learning environment should strive to be free from the pressures of daily life as much as possible to have the best effect. If this freedom cannot be achieved, the process of learning, which also includes time for reflection and maturation, cannot reach its full potential (Alhadeff-Jones, 2017).

Other interviewees also experienced different qualities of time during learning. Interestingly, two interviewees referred to learning in adulthood as a “relaxing activity in free time”. Karl reported: “I am happy to experience learning now, in adulthood-I have chosen what and how I want to learn-it is completely different from school, I am really enjoying it”. The expression “quality time” was also present in the Hungarian interviews. In relation to the financial aspects of adult learning, Peter said:

Since my income has risen, in the beginning we spent it on holidays…, now that we are older, my partner and I am happy to spend it also on non-formal learning, as in a way it’s just like a holiday, even without the travel.

Interpretation, conclusions and outlook

Some of the latest European documents show a general shift from education as public or welfare benefit to the individual responsibility for (lifelong) learning-mainly driven by an economical interest in employability or being employable (see Chapter ‘Comparing gender facets and temporal constraints in adult learning and participation’). The individual is now responsible to find and take time for learning to gain the required skills and competencies. The “autonomous learner is central” as the Council Resolution on a Renewed European Agenda for Adult Learning (Council of the European Union, 2011) states. Like the characteristic slogan of modernity: “Time is money!” (Benjamin Franklin), learning activities are disciplined by the modern sensitivity of a good (productive) use of time, while humanistic meanings of learning as a way to Bildung are shrinking. Following the statistical data for Slovenia and Hungary, adults tend to participate more in job-related adult education. In Slovenia around 80% of males and females participate in job-related education whereas the share in Hungary is around 55%. In both countries the difference is in favour of males (in Hungary 2.2% and in Slovenia 3.6%). Participation in non-job-related education is significantly lower in both countries at around 20% of females and males. The difference between gender is smaller than in job-related education, however it is in favour of females in both countries (in Hungary 0.5% and in Slovenia 3.6%). The higher share of participation in job-related education could be connected to the policies in both countries, which overemphasise job-related education (see Sections ´Adult education, policies, legislations and organisations (programmes)´and ‘Time-policies affecting participation in adult education’). Regulations and Acts (e.g., paid educational leave) leave non-job-related education less regulated in terms of time and leave this sphere to individual praxis and personal engagement. This situation is mirrored in our interviews, especially within the descriptions of how most interviewees struggle to find extra time beside their engagements in work, family life or childcare. Some of them point out how low the support, for example, by employers is and the importance of their individual, personal engagement for their learning.

As we have seen from the gender time-gap, “time spent doing care, domestic work and social activities” by gender EU-data (see Table 5), women in Slovenia and Hungary spend more time caring for children, elderly or people with disabilities and doing housework than men, which leaves them, chronometrically speaking, with less time for adult education. This is also evident from the interviewee’s words: “I did not have time for non-formal education in the last year when my family greeted the fourth member.” Concerning the gender time-gap in Hungary, and even more in Slovenia (cf. European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020c), women are more often responsible for family tasks and domestic work than men, which has a direct influence on their participation in learning. This is not an individual problem, but a problem of missing collective lifelong learning supportive structures. We want to emphasise the prevalent understanding (norms) of gender roles in society and their consequences, as we have noticed, for example, in the words of Eva: ”If I had a family, I probably wouldn’t take part in the additional courses”. Maria said: “Since I have three children to take care of (kindergarten to elementary and secondary education) all with different tasks, it limits my time a great deal to spend with my desired activities”. Leccardi (2005) has indicated that especially young women know maternity can bring a reorganisation of their private sphere, such as family life, and their public sphere, such as work, and can result in the necessity of giving up some “life-projects” (Leccardi, 2005). This could also affect non-formal learning as part of a life-project.

As a unifying temporal element within the interviews and beside gender, time is of central importance for the biography. “While reconstructing past biographical events and processes as relevant for our learning today, we - at the same time - refer to ‘our future biographical projections’” (Schilling & O’Neill, 2020, p. 2). The triangulating, comparative approach - quantitative data (European and national surveys) and qualitative data (11 interviews with (non-)participants) - offered insight into the temporality phenomenon of participation, adult learners’ engagement in learning and diverse constraints. First, the time obstacles for learning are transcultural. Both countries described a lack of (employer) support between work, family and inconvenient time offers. In a methodological reflection, both mega-categories (time and gender) have quantitative and qualitative evidence as comparative category. A value that goes beyond this arises in particular from the relational intertwining of both. For example, temporal well-being in learning itself (“time oasis”) reveals the effort to achieve “temporal resilience” - independent of gender. We could show that the consciousness for time and the awareness of temporal resources, limitations and challenges seems even higher for women.

In the researched subject of time-related constraints, it was definitely the qualitative research approach that could effectively help detect specific indicators for participation and non-participation in ALE. By looking at the wider benefit of learning beside the aspect of economical enhancements of productive time, the interviewees talked about temporal oasis, facets such as “rhythmic harmony” (Alhadeff-Jones, 2017), deceleration, time diversity and enrichment. Some pointed out the social time factors in learning and the well-being coming back to their families. Such a focus on (temporal) well-being through learning reveals important aspects, for example, for public policy, actors in ALE, and for professionals. The insights of the researched context foster the importance and need of more advocacy for learning time, although, the grade of eligibility and supportive legitimations, for example, by (paid) educational leave seems to have no gender-specific influence. Such legislations and acts in both countries observed are not obsolete, but, still not that supportive (for women and men) as they could be (Heidemann, 2021). The consequence of this is, first, that the realisation of learning time still strongly depends on personal engagement and advocacy (e.g., given by employers, family members, partners). Second, the quality of learning time still differs between job-related learning and non-job-related learning, regardless of formal or non-formal learning activities. Further studies may inquire what implications, for example, “time oasis for learning” may have for women and men in a society experiencing unprecedented levels of stress, mental illness and uncertainty or even anxiety about the future. There is an emerging need to dedicate further research to this area to devote more knowledge and comprehension of the complexity of temporal tasks in the dynamic of adult life, within the different life phases women and men need to face. Finally, leading through sociohistorical norms and values, we are confronted with how we approach and shape these temporal challenges as individuals, as adult learners and future professional actors.