According to the American psychologist Howard Gardner (1994 / 1983), there are at least eight types of intelligence: linguistic, logical-mathematical, musical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and naturalistic. However, the ninth intelligence, the existentialist, also studied by Gardner, had not yet been completed by the end of the present work, which is why we did not discuss it in this project. The first two types of intelligence are the most noticeable in our educational system, which does not generally include activities that seek to develop multiple intelligences in a balanced way in Brazilian educational programs. The workload dedicated to Mathematics, Portuguese, and other curricular components that require a lot of reading is predominant. However, some subjects such as Arts, Physical Education, and foreign languages, mainly English, whose teaching has been broadly extended, including in Brazil, must be rethought regarding the assessment and activity system, as they require abundant dynamics in classes. Considering this, some schools have already adopted more recreational activities, with games, more student participation, ways that differ from traditional classes. However, the planned activities, the materials used, and the strategies of English teachers in the initial grades do not seem to contemplate the approach of multiple intelligences.

Every child has a way of expressing themselves. Some are shyer and perform better in individual activities. Others are more expressive when teachers use dynamics, when they can represent or work with their bodies, for example. There is no singular way to raise a child or mediate a classroom with many different children. Each school year is unique and working with children means respecting their particularities. They have their own time to learn, respond and participate. Consequently, the mediator must be attentive to their class and the designed activities so that all children can enjoy as much as possible according to their potential.

The present work aims to analyse the activities planned by an English teacher of the 2nd year of Elementary school. The research aimed to identify and describe the activities and materials used by the teacher, analysing whether the activities meet the proposal of multiple intelligences. We raised the following questions: do the activities planned, the materials used, and the instructional strategies of the English teacher in the early grades seek to develop multiple intelligences? In what way? From these questions, we raised a hypothesis that lesson planning does not contemplate all types of intelligence.

The study aims to identify and describe the activities planned by the English teacher, the materials used, and the instructional strategies. We also seek to analyse whether the planned activities reach the development of multiple intelligences. We qualitatively and quantitatively examined the activities proposed, relating them to the skills they intend to develop (linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and naturalistic).

We specifically intend to identify the activities proposed by the English teacher in the period of a didactic unit, examine the objectives of each activity and the skills developed, relate the objectives of each activity to the multiple intelligences, categorise such activities based on the list of multiple intelligences and suggest activities for the types of intelligence not contemplated by the teacher in the planning.

With the globalisation process, one of the factors that have considerably increased the importance of English in today's world, mainly because of the economy, the number of people who want and/or need to learn the language has grown, and schools have taken advantage of this opportunity to focus on teaching the English language. Although, as Chagas pointed out, this subject has been officially part of the school curriculum since 1937:

Modern languages then occupied, for the first time, a position analogous to that of classical languages, although the preference given to Latin was still very clear. Among those were French, English, and German for compulsory study, as well as Italian, optional; and among the latter appeared Latin and Greek, both obligatory. (Chagas, 1967, p. 105 - our translation)

Therefore, English language teaching has been the object of study in multiple types of research that have produced a wide range of methodological paths. These paths consider crucial aspects that influence language learning, such as behaviour, social and didactic factors. The different learning styles and intelligence are some of these academic concerns. Some studies point to distinct methods for learning a language, either through repetition or conversation, for example, or through activities in which students can practise the language. Santos (2020) points out some foreign language teaching methods that had different objectives, such as learning grammar through translation, working on reading and writing with questionnaires, developing orality through structural exercises, and learning through videos. Riddell (2014) states that the teaching of grammar must be contextualised through situations in which the child can be inserted, because, this way, they can visualise the purpose of the class. We can understand this statement as supporting the idea that children should participate in classes as agents and not as patients/mere receivers. Therefore, activities need to develop intelligence types. Thus, teachers must consider that: "(...) there are at least some intelligences, that these are relatively independent of each other and that can be modelled and combined in a multiplicity of adaptive ways by individuals and cultures”2. (Gardner, 1994 / 1983, p. 7- our translation).

Teachers can validate other approaches (play, music, games, among other recreational activities) to contemplate different types of intelligence in the varied universe that a classroom is. Tomlinson (2014) affirms that teachers in differentiated classes “do not aspire to standardised, mass-produced lessons because they recognize that students are individuals and require a personal fit. Their goal is student learning and satisfaction in learning, not curriculum coverage.” (p. 4). Although it is an arduous task, it is possible to gradually improve English teaching in schools, to ensure most students learn the language. Franze (2008) states that the students had the opportunity to identify themselves in their preferences and actions, and the activities fostered a sense of good relationship, organisation, and responsibility among them.

In addition to observing the students' characteristics, dialogue in the classroom is also essential, as knowledge exchange is part of the relationship between the teacher and the student. The mediator teacher helps the student in the discipline and respects their limits and the differences in their class. According to Souza and Ferreira (2020), “teaching is a discursive scenario of interactive exchanges”3 (p. 10 - our translation). Likewise, it highlights the relevance of recreational activities in which they help in the dynamics of English classes, managing to expand the contents to reach all types of intelligence and allow each student to feel more motivated, participate and interact more (with the teacher and peers). Silva (2018), who aimed to propose reflections on the interaction of children between 5 and 6 years old with their teacher, states that the role of the adult is fundamental to provide learning strategies when students have different rhythms, interests, desires, and needs.

Therefore, this work also intended to alert professionals of teaching foreign languages about the importance of considering the specificities of student learning because the same subject can be approached in multiple ways, thus expanding learning opportunities. In addition, addressing the importance of lesson planning was also part of this project to awaken teachers to improve their performance and that of their students. Although not mandatory, the lesson plan is essential for a successful class because the teacher can think about the objectives and expected results. The lesson plan is a guiding instrument for the teacher. (Conceição, Santos, Sobrinha, & Oliveira, 2019). Our analysis and suggestions were based on the table of pedagogical activities proposed by Armstrong (2001). This way, other professionals and even parents can become aware of the importance of contemplating multiple intelligences.

Conceptual and Categorical View of Intelligence

For many centuries, researchers have been looking for ways to measure the intellectual level of people. According to Scheeffer (1968), the creation of psychological tests took place through the evolution of Experimental Psychology in the 19th century. In 1879, the German psychologist Wundt founded the first Experimental Psychology Laboratory. Then, Galton developed some psychological tests based on Darwin's principles of human selection and adaptation. But it was not until 1905 that Binet and Simon devised the first modern intelligence test. This type of test attempts to measure how quickly and accurately a person can solve problems, indicating raw intellect. However, Binet had already noticed that each person responded differently to the tests (Silva, 2002).

In the 1980s, the American psychologist Howard Gardner, after much research, postulated the theory of Multiple Intelligences. He noted that the Intelligence Quotient Test (IQ) only covered logic and linguistics. Thus, he initially presented seven skills: Linguistic, Logical-Mathematical, Spatial, Musical, Bodily-Kinesthetic, Intrapersonal, and Interpersonal, and then the Naturalist and Existentialist candidates of intelligence. Thus, this conception has brought a new perspective to the understanding of intelligence in the field of Psychology.

In the classic psychometric view, intelligence is defined operationally as the ability to answer items on tests of intelligence. The inference from the test scores to some underlying ability is supported by statistical techniques (...) Multiple intelligences theory, on the other hand, pluralizes the traditional concept. An intelligence is a computational capacity-a capacity to process a certain kind of information-that originates in human biology and human psychology. Humans have certain kinds of intelligences, whereas rats, birds, and computers foreground other kinds of computational capacities. (Gardner, 2006, p. 6)

The concept of cognitive style in cognitive science is like the idea of categorisation of multiple intelligences proposed by Gardner, since both consider the abilities of everyone who has an aptitude for logical sequence or creativity, for example, thus influencing the learning process. According to Oliveira, Santos and Scacchetti (2016), “learning can be conceived as a continuous action that encompasses aspects such as environment, emotions, values, and constant improvement.”4(Oliveira, Santos, & Scacchetti, 2016, p. 128 - our translation). These aspects can be found mainly in language teaching.

The Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Although Gardner (1994) defined Multiple Intelligences, he bases his ideas on previous texts by authors such as the neuroanatomist Franz Joseph Gall. Gall's initial research on the location of brain disorders caused uproars, mainly of a religious and scientific nature, but was later accepted in England and the United States. There was no exact moment or how he designated the abilities in Multiple Intelligences as he reveals “I don’t remember when it happened but at a certain moment, I decided to call these faculties ‘multiple intelligences’ rather than abilities or gifts.” (Gardner, 2003, p. 3).

Gardner was uncomfortable with the theories presented so far, especially with IQ tests, which he considered unfair, as they “focus on a certain type of logical or linguistic problem solving” (Gardner, 1994, p. 20). For Gardner (1994), intelligence is relative, as different types are perceived separately and not compared with each other, that is, intelligence A cannot be minimally compared with intelligence B, although both are types of intelligence.

Since they are limited because they only contemplate two skills, IQ tests would restrict the very person who would perhaps dedicate themselves only to subjects related to these two types of intelligence. That way, people who excel in other skills would be ignored and might even feel inferior. However, according to Freire (1996), “we are conditioned beings but not determined”5 (p. 11 - our translation), that is, we are not limited to doing anything. Children can perform activities that favour different types of intelligence.

The Official Authoritative Site of Multiple Intelligences (Gardner, 2021) presents the classification of multiple intelligences proposed by Gardner: (1) linguistic intelligence includes people who are comfortable with words and their order. (2) musical intelligence is characterised by the tendency to sing or create songs, follow the rhythm, timbre, among other aspects of music. (3) logical-mathematical intelligence is defined by the tendency to solve logical situations and calculations. (4) spatial intelligence is characterised by the ability to conceptualise scales in space, that can have a notion of both abstract (air, earth) and concrete (architecture) space. (5) bodily-kinesthetic intelligence is determined by the ability to use the body to express oneself; (6) interpersonal intelligence is defined by the ability to sensitise and interact with people. (7) intrapersonal intelligence includes people who, like interpersonal intelligence, sensitise and interact with people, but it is self-directed. (8) naturalistic intelligence is described by the ability to recognize natural space, plant, and animal species.

Thomas Armstrong, the author of books in the field of Education and an educator, follows Gardner's theories and explains that:

MI theory is not a “theory of types” to determine which intelligence fits. It is a theory of cognitive functioning and proposes that each person is capable of all eight intelligences. The eight intelligences work together in a unique way for each person.6 (Armstrong, 2001, p. 22 - our translation)

Even if one type of intelligence is most noticeable in each of us, we can develop all types of intelligence. In addition, it is important to note that measurement tests can be unfair, inappropriate, or biased and, in most cases, limited.

Theory of Multiple Intelligences in Foreign Language Teaching

The Multiple Intelligence teacher writes on the whiteboard but also uses other strategies to make all the students understand the topic, such as drawings, songs, videos. The teacher’s role is that of mediator, when they provide activities in which the students get involved and has students interacting in pairs or groups. (Armstrong, 2017). But, most importantly, the Multiple Intelligence teacher will observe their class and plan according to what their students need.

The activities provided by English teachers in schools should attend to the specificities of the students and the abilities of each one, making different dynamics that contemplate the multiple intelligences studied by Gardner. It is challenging to pay greater attention to the whole class and develop a plan that favours everyone, but the school would have a higher quality of education if that were possible.

Teachers, therefore, should think of all intelligences as equally important. This is in great contrast to traditional education systems which typically place a strong emphasis on the development and use of verbal and mathematical intelligences. Thus, the Theory of Multiple Intelligences implies that educators should recognize and teach to a broader range of talents and skills. (Brualdi, 1996, p. 3)

It would not be feasible to include skills in all activities, but even if students feel considered during them, even once a week, it will very likely increase satisfaction and better performance in classes. Working with a 2nd year class of Elementary I is challenging because students are at an age where they can reflect and question, but it can also be rewarding because of the class’s greater participation in activities when compared to previous grades, as psychiatrist Konkiewitz (2013) states:

(...) the child is just transitioning between the pre-operational stage and the concrete operational stage; gradually, the intuitive, rigid, and irreversible structures become mobile, more flexible, decentred, and reversible. (Konkiewitz, 2013, p. 48 - our translation).

According to Piaget's theory of development, in this phase of concrete operations, the child leaves the moment of selfishness and can logically establish relationships between different points of view and perform operations mentally (Terra, 2010). Completing this idea, in addition to systematic teaching, Vygotsky states that the toy also has a fundamental role in the subject's learning process when he says, "that although the toy is not the predominant aspect of childhood, it exerts an enormous influence on child development." (Rego, 1995, p. 80). That happens because the child idealizes commitments through toys. In this manner, the teacher can put this theory into practice in the classroom, taking play objects for students to associate with the subjects or even suggesting that they create their toys, making English classes more dynamic and enabling better student performance.

Considerations About Class Planning

The theme is substantial to help teachers with their students' learning process. Often, because of the everyday hustle and bustle, it is hard to meet all the needs of students. Nevertheless, it is part of the teachers' commitment to present sufficiently diversified contents so that all students can learn.

Therefore, there must be communication between the teacher and the class. Multiple intelligences will be present in every classroom. Thus, teachers must plan their activities and try to contemplate the skills perceived in their students. However, it is common for classes and assessments to be focused only on linguistic and logical-mathematical types of intelligence. Ballestero-Alvarez (2005) warns of this:

When our educational system focuses exclusively on mathematical or linguistic ability, we are limiting and impoverishing the importance of other forms of knowledge and intelligence. It is precisely for this reason that many of our students fail to demonstrate mastery of traditional academic intelligence; they receive little or no recognition for their efforts, hence their contribution to school and society is lost.8 (Ballestero-Alvarez, 2005, p. 10 - our translation)

Some schools work on body expression and music skills in a way that is restricted to the discipline of Arts, which is not enough for students whose intelligences are primarily bodily-kinesthetic and musical, respectively, to feel contemplated. Other courses could stimulate those types of intelligence, such as English classes.

According to Piaget, a seven-year-old child is in the concrete operations stage, the age studied in the research. This phase includes the “development of the ability to reason about objects or real experiences”.9 (Berns, 2002, p. 24 - our translation). Therefore, based on the concept of multiple intelligences and the table presented by Armstrong (2001), some activities can be carried out in the classroom to cover all students. It would be interesting for the teacher to carry out activities involving words such as word searches, gallows, reading, among many others, to develop linguistic intelligence. Musical intelligence could be encouraged with singing, rhythm, and instrument use. Participating in bingo with numerals, counting objects, solving riddles, and other similar games are ways to encourage logical-mathematical intelligence. Spatial intelligence is strengthened by drawing or working with maps. Body-kinesthetic intelligence is designed with body expression activities such as dance, theatre, and performances in the classroom. Interpersonal intelligence is increased if students share moments, work with peers, interact and participate in debates and discussions. Intrapersonal intelligence refers more to individual activities in which the student feels more comfortable reporting something experienced by themselves. Teachers can work with plant and animal subjects and bring samples into the classroom, or even take students into a natural environment so that students have direct contact with what they are learning and optimise naturalistic intelligence.

The experiences and training of teachers inspire lesson planning. Even so, as the specificities of their class supply the planning, the teacher needs to consider the diversity found in the classroom and seek to vary the activities to contemplate the full potential of their students and their multiple intelligences. However, as careful as you are, not all planned activities work. External and internal factors can influence the course of classes. According to Padilha (2001), “planning, in a broad sense, is a process that aims to provide answers to a problem, through the establishment of ends and means that point to overcoming it”10 (p. 63 - our translation).

The importance of making a different lesson plan is not just for the teacher to know what will be done in the class, but as intelligence activities for the students, allowing them to also feel recognized and motivated. According to Menegolla and Sant’anna (1991), “planning should be an instrument for the teacher and the student, we would say, mainly for the students. Secondly, it aims to meet the objectives of the school or its pedagogical-administrative purposes.”11 (p. 10 - our translation).

There is no single lesson planning framework to follow. The teacher heeds the standard proposed by the educational institution. However, some authors have opinions on the subject, such as Ullman (2011), who presents the main elements of well-designed planning: determination of the purpose of the lesson, creation of space for students' thinking and discussion, preparation to stimulate the student to think more and propose a time for reflection. For Menegolla and Sant’anna (1991):

The teaching plan, which guides the entire line of action in the classroom, involves a series of elements, such as the teacher, students, content, experiences, activities, the evaluation process and so on; therefore, necessarily, it must be clear and simple to be viable, because its understanding can be executed.12 (p. 66 - our translation)

Paro (2014) addresses the students' behaviour in the classroom and states that students spend a long time sitting in chairs and speak very little. Most of the time, the teacher talks throughout the entire class. Students need to express their opinions, make suggestions, and ask questions. This way, the teacher will be more capable of perceiving the development of each student and identifying the intelligence that stands out in each one. In a better perception, it is necessary to have this participation in English classes, as it is a discipline that involves dynamics, dialogue, and total interaction of the students in the classroom. Students will not be obliged to speak in class but, as Paro says, it is the teacher's role to captivate the students so they want to learn. However, not everyone does this:

This way, the teacher assumes absolutely no responsibility for the student's failure. In the first place, it would mean assuming their incompetence in the organisation of pedagogical work, an inadequate presentation of stimuli for learning. Second, what they do usually translates into positive results. That is, some students, or most, learn. If the action produces behaviour modification in some students, then the problem is with the students and not with the teacher's action. Without going beyond the behaviourist view of knowledge, no other hypothesis is raised by the teacher about the difficulties that students present, other than their inattention and disinterest. Thirdly, because, consistent with such a view of knowledge, assessment is reduced, for them, to the observation and recording of the results achieved by students at the end of a period. Such a view does not absorb a reflective and mediating perspective of evaluation.13 (Hoffmann, 1994, p. 54 - our translation).

Hoffmann (1994) reaffirms what was mentioned earlier about the teacher's attitude towards students. In the classroom, the teacher makes an overview of the class and takes the majority's grade as something positive: if it's good, the teacher did a good job, forgetting about the others who didn't reach the unit or assessment average. So, the mediator must consider all the students, considering every intelligence.

According to Antunes (2016), the teacher in the classroom works as a mediator who helps the student find answers or solutions. For the teaching processes to take effect, Antunes (2016) suggests a tripod: knowing how to teach, knowing your students, and mastering the contents. In addition, the teacher also needs to work with significance because it is necessary to contextualise the subject worked on by the students, making them able to use this knowledge in different skills. According to Santos, Brito and Maranhão (2014),

(...) for there to be a good development of teaching, it is necessary, in addition to the legal apparatus, to plan, reviewing practices and evaluating learning, meaning that the teacher should not only be concerned with the 7 pieces of information that will be passed on but also with the individual process with which each one builds their knowledge because for the group of students the teacher appears as the experienced figure capable of exchanging the necessary information when they are having some difficulty and for this to happen he needs to be aware of his work as a facilitator who gives importance to students' doubts and uses dialogue to promote their learning.14 (p. 6 - our translation)

The mutual relationship between teacher and student has already been mentioned, but we must also address the student-student link, as it is necessary for development in the classroom. Students who interact more express their opinions more, ensure dialogue with their colleagues, respecting the other's point of view and, thus, developing their criticality more. This participation is more common for students with interpersonal intelligence, but the teacher must encourage other students to promote everyone's participation in the classroom.

Methodology

This documental research proposed a descriptive study about the approach of multiple intelligences proposed in the planning of didactic activities by the English teacher of the afternoon classes of the 2nd year in a private school in Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil. This study considered quantitative aspects investigating the frequency of activities for each type of intelligence and qualitative aspects identifying and describing activities and resources used by the English teacher.

The target planning is for the 2nd year class of Elementary I (7-8-year-olds). The institution serves children from Kindergarten (Group 3) to the 5th year of Elementary School and offers Portuguese, Mathematics, Geography, History, Science, Physical Education, English, and Arts courses. According to the school principal, the institution chose to have English classes only once a week to emphasise Portuguese and Mathematics subjects since they are the most demanded areas in Brazilian society.

The study corpus consists of eight lesson plans provided by the English teacher. The table with the abilities proposed by Gardner supported the analysis. After comparing the activities and types of intelligence, we carried out a quantitative survey of the activities that include such skills.

The lesson planning of unit 4 of 2016 was made available by the teacher of the investigated classes. We analysed the activities from the perspective of Multiple Intelligences, according to the theory of Howard Gardner. The analysis was detailed, observing whether the teacher elaborated each activity privileging each intelligence. The data analysis instrument was a guide developed by the author. The analysis was based on a framework of pedagogical activities that contemplate different types of intelligence.

Results and Discussion

The teacher developed a lesson plan for a 50-minute class. In this school, English classes take place once a week. Therefore, we have eight plans referring to the 4th academic unit. Each lesson plan presents the objectives, development, and activities. In the analysis of each lesson plan, we highlight the type of intelligence contemplated and suggest activities, materials, and procedures that consider other types of intelligence based on Armstrong's table (2001), which is attached, although it is not possible to cover all skills in just 50 minutes of class.

As we have seen, the teacher must write the daily planning clearly and objectively to guide the headteacher. Activities, developments, and objectives must be linked and very well explained. The teacher must establish a goal that the student must achieve through the activity proposed. Regarding the activities, the teacher will offer methods to make the student understand the topic studied so they can use simple activities such as graphic activities to great performances, according to the subject worked in the classroom.

We present the analysis of the daily planning of the 4th unit made by a teacher of the 2nd year of Elementary School below.

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 1 - Lesson 1, Museums.

Objectives: to relate words to images in the reading of the entrance ticket, proposed by the book; to know the types of museums and their nomenclatures.

Development: the children will hear on the CD the information that is in the book about the entrance ticket to the museum; point out the words on the page, linking them to the information contained in that ticket such as museum name, address, contact information, price, and opening hours; analyse, on the next page, images of types of museums with the help of the teacher and the audio.

Activities: ask the children if they know any museum and its theme, ask them to introduce themselves one by one in front of the class; write words like dinosaur, natural history museum, and others related to museums on the board and work on pronunciations and meanings.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic, Logical-Mathematical, and Interpersonal. Resources: radio (CD), book, and board.

In this planning, the teacher asks students to relate the words to the images of the entrance ticket presented in the book. The teacher was contemplating linguistic intelligence. The child will analyse the words' meaning, a characteristic of linguistic intelligence, according to Gardner. Relating words to images favours logical-mathematical skill. By proposing that children present themselves in front of the class to talk about museums, we infer that the development of interpersonal intelligence is sought.

As this plan covers only three of the eight skills presented by Howard Gardner, some suggestions are feasible to cover the remaining five. Therefore, based on Armstrong's (2001) table, for spatial intelligence, a museum mapping activity could be carried out. Proposing a play in which students would play the role of museum visitors and employees would contemplate bodily-kinesthetic intelligence. Singing some song with the theme or making some rhythm with the words used in the vocabulary would consider musical intelligence. For intrapersonal intelligence, the student could report an experience with museums by writing a text or even answering questionnaires on the topic. For naturalistic intelligence, a discussion could be developed about what kinds of animals or plants are on display in the museums listed in the class.

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 1 - Lesson 2, Museums exhibits.

Objectives: to relate words to images in the reading proposed by the book, to know the types of collections that museums present.

Development: drawing attention to images, introducing vocabulary, and practising pronunciation; saying the words or listening to the CD twice for the children to repeat afterward; talking about the “exhibits”, for the children to point out in the book or on the board the correct answer about the images.

Activities: responding to the book activity by linking the learned phrases to the correct pictures; playing “exhibits and names of museums”, which consists of writing on the board enumerated words, in a column, of themes that are presented in museums, and, in another column, the type of museum presented, asking children to enumerate the answers.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic and Logical-Mathematical.

Again, in this planning, the teacher proposes that students relate words to images, contemplating logical-mathematical intelligence. Next, children develop linguistic aspects by practising pronunciation. During the planning, only these two skills were being considered, as writing the words on the subject on the board and enumerating them meet, respectively, the linguistic and logical-mathematical types of intelligence.

Although it is not feasible to practice the 8 skills in a single class, some suggestions are valid for this topic so that the other types of intelligence are stimulated. According to Armstrong's (2001) table, teachers could create mapping activities for spatial skills. Questionnaires about experience reports can be made to contemplate intrapersonal intelligence. Creating an activity that contemplates several types of intelligence at the same time is also valid, for example, creating a play in which some students are museum employees and others are visitors. In this museum, there can be musical performances with dances on the topic studied in class, exhibitions of plants and animals. So, here we can find the bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, musical, and naturalistic types of intelligence.

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 1 - Lesson 3, Want / Need.

Objectives: to guide children to know the two verbs, differentiating the meaning of each one.

Development: with the help of the teacher and/or the audio, to ask the children to listen a few times to the sentences that contain the verbs “want” and “need”; then, translate the words and the meaning of each one, writing on the board, illustrating, or also talking about daily desires/wants and needs.

Activities: responding to activities in the book about the meaning of the verbs to want and to need; asking the children to present themselves in front of the class and talk about their wants and needs, based on a vocabulary, in English, prepared by them in advance or in the form of a question-and-answer game: “Do you want to...? / Do you need to...?”. Responses: “I want to...” and “I need to...”.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic, Intrapersonal, and Interpersonal. Resources: Radio, board, and book.

In this planning, the teacher uses the book to answer questions. The professional also works with the translation of words and the meaning of each one, contemplating linguistic intelligence. Then, we identify interpersonal intelligence when the teacher suggests that children present themselves in front of the class to talk about their desires and needs and dialogue using structures proposed by the teacher. We also identify intrapersonal intelligence since children need to reflect on themselves to know their desires.

In this class, we could also work on musical intelligence with rhythm, parodies, and rhymes about this theme, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence with body movement such as dancing or even creating something through their desires (the topic of the class), and children can talk about animals and plants they wish to have (naturalistic intelligence). The teacher could create games with the theme or a graph according to the number of students who want and need something and generate a discussion about the average of the data (logical-mathematical and spatial intelligence).

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 1 - Lesson 4, Museum ticket; dinosaurs.

Objectives: to observe the information in the entrance ticket to the museum and learn a little about the types and measurements of dinosaurs.

Development: drawing attention to the ticket information, asking children about what is in it: the image, the name, entry time, price. Such information will serve to answer the activities in the book. As for the “dinosaurs”, children will read the information about the “T-rex” and then choose their dinosaur from the extra sheets at the end of the book.

Activities: answering the book activity that consists of replying “yes” or “no” to the information contained in the ticket about the museum and others; regarding the dinosaur, each child will cut out their favourite dinosaur from the extra sheet and paste it on the corresponding page, putting the information about the one they chose and presenting it to the class.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic and Interpersonal.

In this planning, we noticed that (1) linguistic skills were considered, as the children, in addition to answering the teacher's questions, will answer the questions in the book and read information about dinosaurs, and (2) interpersonal skills were also considered, because after collecting the information, the students will present them to the class. However, stimulating another type of intelligence would be possible: by elaborating an activity with music or asking students to make parodies on the theme (musical); doing a choreography activity (body-kinesthetic); measuring the size of dinosaurs or asking students to create a dinosaur statue using different materials and asking them to measure it (logical-mathematical and spatial); cataloguing information about dinosaurs such as the environment in which they lived, what they ate and species (naturalist); reporting activities (intrapersonal intelligence).

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 2 - Lesson 1, Types of Puppets.

Objectives: to show children the different types of puppets and marionettes to their interest in this art. In addition to knowing the categories, children will learn to pronounce them in English.

Development: drawing attention to the images in the book and asking the children to repeat the vocabulary. Then pointing to the picture and asking the children in English (What is this?), getting the correct answer from each child or group.

Activities: answering activity 1 of the book, enumerating each picture with its correct alternative, and activity 2, asking and answering about the proposed images, in the format of: “What is it?” and “It is a...”; showing the students some types of puppets made for a moment of conversation and relaxation with the children, naming the character and having it interact with the class by asking questions and getting the answer in English.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic, Interpersonal, Logical-Mathematical and Bodily-kinesthetic.

Resources: puppet and book.

In this activity, the following skills are covered: (1) linguistics, as the teacher asks children to repeat vocabulary and answer questions based on the book. In a group, this activity would also stimulate interpersonal intelligence. (2) logical-mathematical, as children will enumerate the figures in the correct alternative, that is, it is a catalogue activity that meets this skill, according to Armstrong (2001); (3) bodily-kinesthetic, through the use of puppets and theatre; and, (4) interpersonal intelligence, because in addition to the group activity, there are also questions and answers with the puppet in the moment of relaxation suggested by the teacher. The teacher could also consider Interpersonal intelligence by elaborating a report text using the expression “It is a...”. They could also use rhymes and songs to animate the puppet (musical intelligence). An optical illusion activity, for example, can be done and still practice the expressions of the day: “What is it?” and "It is a...". A discussion can be raised with subjects about animals and plants, showing images of them and asking the children if they know what they are and where they live and, thus, also work on the expressions of the day.

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 2 - Lesson 2, The Ant, and the Grasshopper.

Objectives: to present the play The Ant and the Grasshopper in English to learn some keywords contained in the text, in addition to having contact with a plot entirely in English.

Development: choosing children for the three lines of the play: narrator, ant, and grasshopper, the last two characters being able to be accompanied by puppets made by the children.

Activities: in addition to the theatrical play first, answering the book activity on the plot of the play, related to some highlighted words from the text.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic, Interpersonal, and Bodily-Kinesthetic. Resources: materials for the play and book.

When planning this class, the teacher was able to pay attention to some types of intelligence: linguistics with the book activity; interpersonal and bodily-kinesthetic with the theatrical play. The other cognitive styles could be considered in the following ways: (1) musical, spatial and naturalistic skills can be focused on the piece itself from music and rhythms, construction of the environment of the piece, and the in-depth study of the insects in question, respectively, (2) the logical-mathematical, through reasoning games with the theme of the class and (3) the intrapersonal, through a presentation focused on feelings, even representing one of the insects in a poetic way.

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 2 - Lesson 3, Like to / Don’t like to.

Objectives: to guide children to know the two expressions in the English language and their meanings.

Development: asking children to express themselves, telling them what they like or do not like to do. It can be on any topic, working in first person in English.

Activities: answering the activities in the book about the expressions studied; Plaque game: this consists of making two plaques with the words “I like” and “I don't like”, which will serve for the children, individually or in groups, to answer questions - a plaque for each answer, positive or negative.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic, bodily-kinesthetic, Intrapersonal, and Interpersonal. Resources: Book and materials for making the signs.

The teacher suggests working with activities that are considering 4 of the eight skills proposed by Gardner: linguistics, with activities from the book; bodily-kinesthetic with the production of signs; intrapersonal, because the children must think about themselves, since they will have to answer a personal question about liking or disliking something; interpersonal, with group work.

Thus, we can suggest the elaboration of activities that contemplate the other types of intelligence, such as the construction of a graph to know in average how many students like or don't like something presented by the teacher (spatial intelligence) or videos and songs in English (musical intelligence).

Topic: Unit IV - Chapter 2 - Lesson 4, The Pig and the Bee.

Objectives: to continue to observe the construction of dialogue in English.

Development: as in the class of " The Ant and the Grasshopper" play, choosing children to participate in the dialogue with the help of the educator and repeating it with other children.

Activities: filling in the dialogue in the book similar to the one between the “pig” and the “bee”, so that the children create a new title and new names for the characters; making in the classroom a poster advertising a puppet play (cut-outs of coloured letters for the formation of words in English to fill the poster, name of the characters in the play, place, time, and others), in which everyone can participate.

Intelligence(s) contemplated: Linguistic, Interpersonal, and Bodily-kinesthetic. Resources: Book and cards.

In this planning, we can find the following skills in the activities: (1) linguistic, as the children will fill in the dialogue in the book. (2) interpersonal, with the activity that will make the dialogue from the play. (3) bodily-kinesthetic, because just like the grasshopper and the ant's planning, the children will need to enact the play, and they will also build a poster.

They could also build the scenario (spatial intelligence), create or use a soundtrack for the dialogue (musical intelligence), prepare an individual questionnaire with reports (intrapersonal intelligence), and do research about bees and pigs, which would also enrich the dialogue (naturalistic intelligence).

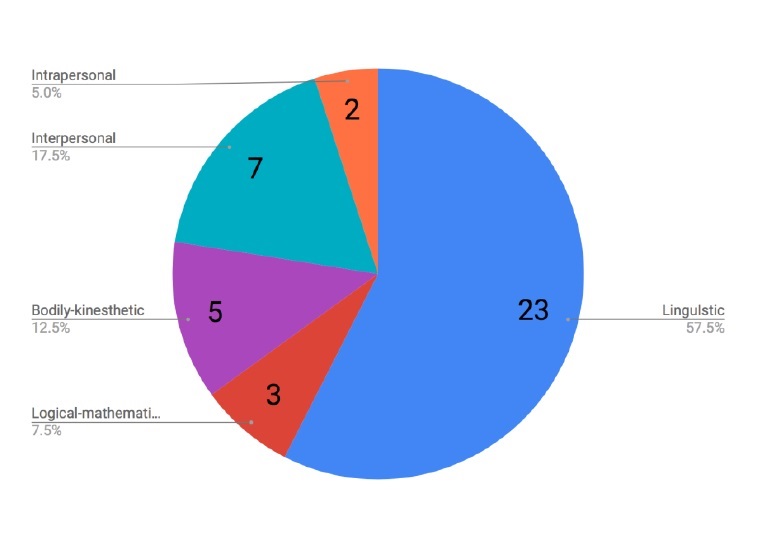

The graph 1 below summarises the percentage of skills covered in the activities developed by the teacher.

Graph 1: Percentage of skills covered in activities developed by the teacher (Source: Created by the author).

Out of 40 activities developed by the teacher, 23 are focused on Linguistic Intelligence, 3 on Logical-Mathematical, 5 on bodily-kinesthetic, 2 on Intrapersonal, and 7 on Interpersonal. Musical, Naturalist, and Spatial types of intelligence were not included in the teacher's classes. Therefore, we can observe that 57.5% of the activities include the Linguistic skill, that is, there is no balance between the number of exercises and multiple intelligences.

It is not the teacher’s mistake to consider one skill more than the others, given that he is teaching a language. In other words, it is natural to have a higher percentage of Linguistic Intelligence. However, other types of intelligence could be more present in the activities.

Such results can be compared to other studies, such as Dolati and Tahriri (2017), who investigated whether there are differences among 30 English as a Foreign Language instructors regarding various intelligence types in activities. As a result, the authors conclude that teachers of the logical-mathematical type were influenced by their dominant intelligent types.

Activities that contemplate multiple intelligences in high school English classes were proposed by Franze (2008). For this, the author used the textbook, music whose lyrics had words in English, questions in which the teenagers could reflect on culture, videos on the topic of the class, films about the relationship between different cultures, group work with movement, making of posters and recipe execution. All activities were contextualised with the English classes. Such research meets Bearne and Reedy’s (2017) statement about the topics discussed in class. According to the author, the objectives must agree with contextual, textual, and pedagogical purposes. For instance, the teacher can work on the topic composition by asking about the children’s narratives, that can be performed individually, in pairs or groups, and analysing them in text, context and pedagogical ways. Scrivener (2013) offers some ideas for activities and tools for teaching grammar, such as flashcards and picture stories for more visual children, and acting for more expressive children, among other activities.

Scrivener (2011) states that, although the textbook offers procedural options for teachers, they are free to proceed differently according to their classes. The author also reminds us that for a successful lesson plan, teachers must become familiar with the material and the proposed activity, try to do it first, think about it from the student's point of view and be prepared for unforeseen events.

Final Remarks

As the research carried out was restricted to the planning of lessons of a unit of a single teacher, the results cannot be generalised. We noticed that most activities are still focused on linguistic intelligence as predicted by our hypothesis. Although many types of intelligence are included in the planning of the investigated English teacher, it was evident that there is not a balanced frequency between them. Therefore, we can infer there is a deficit concerning teaching-learning in English classes since this subject can be approached in a more varied, playful, and dynamic way. More comprehensive research, including the inclusion of public schools, would certainly be relevant to verify if this is repeated in other contexts and throughout the school year.

We suggested how to propose activities to stimulate different types of intelligence and respect the diversity of cognitive styles present in the class. Such suggestions demonstrate the same theme can be approached from multiple perspectives. Although the number of classes per week is not enough to cover all skills, the teacher can propose different activities during the unit.