Introduction

Early on, mankind began to observe the change of the seasons, the rhythms of the moon, and the course of the sun, and we tried to make sense of it. Eventually, we not only developed concepts of time but, on basis of these observations, we also invented instruments and procedures, like the moon calendar or the sundial, by which to measure time. However, measurement is always an act of standardisation, of establishing a shared understanding, and of codifying common-sense constructions. Hence, the measurement of time has contributed largely to making time socially available as a means of coordination and organisation of social practice. The measurement of time can thus be seen as a specific form of the social appropriation of time.

With the beginning of modernity, the natural sciences and their empirical methodisation have contributed significantly to the development and dissemination of a modern understanding of time and, ultimately, have a decisive influence on the way time is dealt with in everyday social life. This modern, scientific understanding of time is a social construct that broadly shapes social reality as it established a doxical relation that mistakes time objectified for objective, as a matter of fact, as natural. Thus, it is the task of the social sciences to question this relation through empirical social research. In order to empirically investigate time as a social construct and its effect on social practice, we are therefore necessarily referred to qualitative (or re-constructive) methodologies.

For educational science, and especially for adult education, such an approach is important because educational processes always require time and, conversely, our experience and handling of time is itself a result of education. As a resource, time is also perhaps the most important limiting factor for educational processes across the lifespan, both on the part of adult education providers and adult learners. Therefore, a reconstructive methodological approach to temporalities in the field of adult education is required.

In this paper, a practice theoretical and field analytical perspective on time and temporality is discussed and confronted with a tempographic heuristic to specify the relevant objects of observation and join these perspectives with the methodological approaches of ethnography. In the interlacing of the three perspectives, a methodological framework for research on temporalities in adult education will be presented.

Time research and education

The modern, Newtonian conceptualisation of time is still extremely influential in our everyday understanding. The idea of time as an endless stream, as something that flows continuously and uniformly, extending from the past into the future, still dominates in media representations and in people’s minds. This stubborn persistence is surprising insofar as not only science - first the theory of relativity and, today, quantum mechanics - questions this image (Rovelli, 2018), but it often cannot even be reconciled with our everyday experience in which time sometimes runs slower or faster, has jumps and interruptions, and rarely runs in line with the time experienced by family and friends. It was the social sciences that questioned this prevalent idea; “Newton’s formulation of the concept of a time which is uniform, infinitely divisible, and continuous” is the “most definite assertion of the objectivity of time” (Sorokin & Merton, 1937, p. 616). In contrast, they emphasised the importance of ‘social time’, which follows completely different rules; it is not uniform (and thus merely quantitative), but also has rich qualitative aspects, it comes in very different, socially defined, and often indivisible units, and it passes at very different rates, depending on the social situation and the actors’ differing perceptions. Furthermore, there is not one social time, but many;

Each group, with its intimate nexus of a common and mutually understood rhythm of social activities, sets its time to fit the round of its behavior. No highly complex calculations based on mathematical precision and nicety of astronomical observation are necessary to synchronize and co-ordinate the societal behavior. (Sorokin & Merton, 1937, pp. 619-620)

Nonetheless, for many social scientists, time still means that which is indicated by the clock and the calendar. Within a “variable sociology” (Emirbayer, 1997), the objectified and standardized measurement of time serves as an essential correlative with which social processes are measured. Most frequently, time-related information is collected as a contextualizing variable in empirical studies. Of course, this also applies to quantitative surveys in educational science, where questions are asked not only about the school-leaving qualification but also about its year; not only about the study programme but also about its duration; not only about further education but also about its hours. It is very easy to collect because it is standardized and because time measurement and logging in our everyday life has a high degree of self-evidence and thus, we are accustomed to indicating time or duration when reporting on certain events or activities. Time budget studies, on the other hand, make objectified time explicitly the object of their investigation by focusing on the everyday use of time and, in particular, they try to provide information on how much time is spent on which activities, such as education, for example. From this angle, time comes into view as a (scarce) resource for learning in adulthood (Schwarz, 2019b) within the temporal basic reference of time consumption (Schmidt-Lauff, 2012). In qualitative research, time initially comes into play as a contextual variable, too, but here, reflections on time clearly take place to a greater extent: time-related information is not to be correlated but is necessary in order to better comprehend what is being reported in chronological order or to directly address time-related qualities of experience. In addition, at least in some areas, there is a methodological reflection on the meaning of time and temporality, e.g., in connection with the narrative constraints of the biographical-narrative interview (Schütze, 1983).

So far, we see essentially three lines of empirical examination of time: in the first, time is used as a correlating datum and indicator; in the second, time is examined as a resource and restriction for action; in the third, temporality as a specific experiential content comes into view alongside objectifiable time. In addition, time and temporality can also be examined in Sorokin’s sense as a result of societal processes, as something culturally produced, and as an outcome of social practice. Education is of particular importance in this perspective because it is only through educational processes that we acquire certain social concepts of time and learn how to deal with it which, at the same time, enables us to participate in shaping and transforming cultural orders of time. Educational science in its core concepts refers to (mostly protracted) processes, in which learning and education take place in time and also establish a certain relationship to time. For adult education, however, this poses a particular challenge because its addressees have already developed specific self-relationships to time (Schmidt-Lauff, 2012) that fundamentally shape their educational practices. For the practice of adult education, a “professional time-sensitivity” (Schmidt-Lauff & Bergamini, 2017) is therefore needed. If these challenges are met, there is great potential for a systematic examination of time in adult learning and education, which also appears to be particularly suitable for promoting its emancipatory potential (Alhadeff-Jones, 2017).

Adult education research similarly requires a time-sensitive methodology, capable of not reducing time to either an objective structure or a subjective experience, but rather to understand culturally specific temporalities as a condition and achievement of social practices in the field of adult education, and to systematically relate these to the educational processes taking place there. In the following section, a suitable social theoretical basis in Pierre Bourdieu’s praxeology will be identified.

Temporalities in the field of adult education: A praxeological perspective

The theoretical foundation of the methodology to be developed here will be located in the theories of practice, especially in Pierre Bourdieu’s praxeology. This is connected not only with a social-theoretical positioning, but also a science-theoretical and finally an epistemological positioning, which asks for the historically specific, socially objectified, and materialized conditions of scientific research and theory formation and bases this question as a necessary moment of reflection on scientific practice (Bourdieu, 1999). Science is conceived as a social practice, and this means making it, like any other form of social practice, accessible to scientific and empirical investigation, and thus ultimately comparable (Bourdieu, 1988).

Time and temporality in practice

For the present engagement with a praxeological temporal methodology, however, it should be emphasized that it was a special moment when science developed a specific temporality in which it is relieved of an immediate time pressure in relation to the practices it investigates and, at the same time, completely in contrast to them. It is a special, socially granted privilege to deal with the most everyday actions and social forms of interaction with all the time in the world in a social scientific study; for instance, when we discuss the meaning of an interview passage for weeks, or even months, publish the results of our analyses perhaps only after years, and perhaps decades later, secondary researchers still refer back to the interview material in order to recognize in it further, previously unexplored aspects. In the original social practice of the interview situation, on the other hand, it was not possible for our counterpart to pause and reflect on the meaning of his statements in an action-relieved manner for an indefinite period of time. Furthermore, science, too, has a concrete practice, which has constraints on action and is subject to the same time pressures, because interpretation sessions must be finished, papers submitted, and projects completed.

This second level of an observation time in science, in relation to the originally observed time, must therefore always be analytically taken into account. Bourdieu’s warning against imposing the ‘timeless time of science’ (Bourdieu, 1993c, p. 148) on the reconstructed social practice is not only of science-theoretical importance but also makes clear how significant time is social-theoretically for the theory of practice. The specific practical logic (which substantially differs from scientific logic) is given by its temporality. Fundamentally, social practice occurs in time, meaning it is not only irreversible but also unstoppable. This implies a dynamic to which the agents involved are committed and which provides a constant pressure to act. Constitutive for coping with this is an economy of practical logic, which is based on practical conclusiveness and becomes controllable precisely through its fuzziness (‘polysemy’ and ‘polythetics,’ cf. Bourdieu, 1993c, p. 157). This fuzziness is also crucial for the contingency of social practice, its openness to the future, and the possibility of social change (Elven, 2020).

The basis for this efficiency lies in the practical knowledge that comes into play as a shared knowledge of the participants of an interaction. It is always situationally embedded, both bodily and materially. Practices must be understood as “embodied, materially mediated arrays of human activity centrally organized around shared practical understanding” (Schatzki, 2001, p. 11). For Bourdieu, therefore, the three central analytical concepts social practice, habitus (i.e., subjectified structures of thought, perception, and action), and social field (i.e., objectified and institutionalized cultural orders) are always strictly linked analytically.

Bourdieu likes to use the example of the soccer game to illustrate the amazing feats agents are capable of in such complex social situations. The long, precise pass to the future position of a teammate, considering the current positions and probable movements of all other players, is precisely not the result of resilient trajectory calculations and mature strategic considerations of 22 individuals, but rather a preconscious, situationally bound, and social performance. However, it is also important to emphasize that social practice not only takes place in time, but also plays with time, and is certainly and preconsciously strategic: speeds, pauses, and rhythms can be meaningful and therefore play a central role in social practice, be it in a soccer game, in a ritual gift exchange, or in education.

In addition to the fundamental temporality that characterizes any social practice, there is a second temporality that is empirically produced within a very concrete social practice (Koch, Krämer, Reckwitz, & Wenzel, 2016). To use the soccer example one last time, Game A may be characterized by high speed, intensive pressing, and frequent goal attempts, while Game B fails to find a rhythm, is slow and, at times, plodding. It is this second, practically produced temporality of concretely observed social practices that will be the focus of the methodological approach to be elaborated herein.

Social fields as temporal fields

As stated earlier, social practices are generally contingent. Thus, mechanisms are needed that help to stabilize practice arrangements and allow agents to have expectations for certain outcomes. These mechanisms are theoretically placed in the two parallel concepts of habitus and field. While habitus represents subjectified social structures that comprise relatively persistent structures of thought, perception, and action against the background of our socialization and educational history, social fields stand for objectified social structures that comprise the current positions of the actors, the codified and latent rules of the game and, above all, the meaning of the game as a result of historical struggles. Although Bourdieu initially dealt prominently with the overall social game and focused on French society as a ‘whole’ (Bourdieu, 2010), the concept of the field gained contours when Bourdieu’s research interest increasingly turned to the specifics of different social fields, such as art (Bourdieu, 1996), science (Bourdieu, 1988), or economy (Bourdieu, 2005).

Bourdieu defines a social field as a

network, or a configuration of objective relations between positions. These positions are objectively defined, in their existence and in the determinations they impose upon their occupants, agents or institutions, by their present and potential situation (situs) in the structure of the distribution of species of power (or capital) whose possession commands access to the specific profits that are at stake in the field, as well as by their objective relation to other positions (domination, subordination, homology, etc.). (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 97)

This definition may seem abstract at first, but this is precisely what makes the concept of field an analytical concept that can be used to describe and analyse very different arrangements of social practices. Thus, it is not a matter of focusing only on what other theoretical traditions would call ‘social subsystems’, but rather a concept that can analytically grasp the objectified structures underlying any ensembles of social practices. Hence, an organisation (Bourdieu, 2005; Emirbayer & Johnson, 2008), or even a family (Atkinson, 2014; Bourdieu, 1998), can be analytically addressed as a social field. This understanding of the concept of field is of particular interest when undertaking a praxeological investigation of time and temporality, because it gives us a first answer to the question where and how do we look for specific temporalities (Atkinson, 2019). Furthermore, this opens up the possibility of using other field-related analytical concepts such as doxa, interest, and illusio to analyse specific temporalities.

Even in his early systematic overview of the research efforts on time in the social sciences, Werner Bergmann (1992) lists time in specific social systems as one of the major research areas. This includes, for example, studies on time in the professions, time in social subsystems such as the economy and the legal system, but also time in organizations and in the family. As shown above, the field concept can provide an analytical framework for all of these cases, thereby also opening up the possibilities for systematic comparative research that asks for commonalities and differences between different fields. At the same time, the question of the relationship between fields and their temporalities arises; while this relationship is often thought of as a hierarchical one, in terms of a stratification of social time (Lewis & Weigert, 1981), the praxeological field concept is characterized by a relational perspective (Emirbayer, 1997; Schwarz, 2019a).

This means we can understand social fields as being like magnetic force fields, which overlap each other many times and may mutually weaken or strengthen one another, but in any case, interfere with each other. Therefore, practice theory only expects a ‘relative autonomy’ of social fields; no field can exist completely free from the influence of other fields, but also no field can be completely determined by others (otherwise it is no field at all). Without falling back into a stratificatory understanding of different social times, we can assume on this basis that a society’s overall conceptions of time cannot leave a concrete field such as adult education uninfluenced. Likewise, the temporality of other educational fields (such as higher education) will influence time practices in adult education, and perhaps vice versa. Nevertheless, the specific, practically produced temporality of the field of adult education cannot be explained by the influences of other fields alone.

Bourdieu’s analysis of social fields

For the analysis of fields, Bourdieu not only gave a variety of examples, but also formulated relatively clear requirements that can serve as an orientation for considerations leading us to a methodology for the research on field-specific temporalities. Bourdieu names three generally necessary elements of an analysis of social fields (Bourdieu, 1993a):

Genesis and Development: How did the field constitute itself? In relation to which other fields did it gain its relative autonomy? How did it develop further?

Objectified Structures: Which positions exist in the field and what are the organising principles for their relative positioning, including the struggles dividing them and the common interests uniting them?

Subjectified Structures: How do the agents perceive the field, and how do their habitus relate to the social practice produced at their respective position within it?

Firstly, social fields can only be adequately analysed when considering their history, going back to their genesis, and reconstructing their further development. The question of how the field under study gained relative autonomy from other fields is especially relevant, as is the consideration of which role these other fields played in its further development. This first approach should be systematically pursued with the research interest in temporalities, to be able to analyse how certain temporal orders (e.g., the duration of a lesson or the time of day at which courses are being offered) arose in the field, where they stem from, and how they developed throughout the history of adult education (Seitter, 2010). The totality of the historically developed relations to other fields spans a space in which the field under investigation becomes recognisable in its relationship to the ‘field of power’, i.e., its overall societal position emerges. Understanding the structure of a field and the structures of its agents is only possible against this background.

Secondly, the analysis of field-specific temporalities also requires an examination of the structure of the field, i.e., the institutionalized positions and their relations, the underlying organizing principles, and the explicit and implicit rules of the game. Of course, this also includes field-specific temporal orders, all time-related rules of the game and the question of the extent to which time itself serves as capital in the field. Moreover, this perspective is directly linked to the question of the distribution of capital, and thus of power, which is relevant not least because time is always contested, and the actors enter this struggle with unequal chances.

Thirdly, the agents and their perspectives on the field must be considered, i.e., analytical attention must be directed to how they reconstruct the temporal order of the field or concrete time institutions within the field. It has also to be taken into account how they deal with them in practice, and how they are thus involved in field-specific struggles about time, e.g., about the value of time spent on different pedagogical activities. The analytical focus thus shifts to the patterns of orientation that the agents show and that are of particular relevance to their time-related practices and practical strategies, finally contributing to the specific temporality of the field.

Before moving on, it is worth summarizing the previous considerations. From a praxeological perspective, time is essential for the specific logic of social practice. Social practice actively ‘plays’ with time and thus produces specific temporalities. As social practice is fabricated in the situational interplay of subjectified (habitus) and objectified social structures (field), social fields were identified as an empirical and analytical access point for the approach to be unfolded. As practices are (historically) materialized and institutionalized there, the specific temporality of the field is also objectified in this way. An analysis in field terms focuses on the historical analysis of relative autonomy, the analysis of the positions and their relations, and the analysis of the practical positioning of the agents. In temporal-theoretical terms, we can then observe how a social field develops its own, relatively autonomous time order, how this time order becomes relevant for and is, in turn, shaped by the different positions, their power relations, and their struggles, and we can look at the perception practical handling of time on the part of the agents.

From the Field of Adult Education to Course Research

Questions that systematically precede these three steps of field analysis have so far been excluded from the explanations: What actually is the field that is being studied? Where do its boundaries lie? Who belongs to it and who does not? These questions are only partly predetermined by the research interest as they are constantly disputed in the social fields themselves. Consequently, this means that a narrowing down of the field of investigation can only take place based on an empirical investigation, so usually a resolution of this dilemma must take place through consistent processuality of research practice. With regards to the research question, however, at least a first delimitation of the level on which the analysis is to move decisively can take place. For the examination of adult education fields, five analytical levels can be distinguished and analytically related:

The field of education

The field of adult learning and education (ALE)

Areas of adult education (e.g., vocational education)

ALE organisations (e.g., providers)

Adult education courses

The concept of the social field can be applied within adult education at very different levels of aggregation while also opening up different empirical access points. On the one hand, each social field is characterised by a unique logic that is not completely reducible to the logic of other fields (Bourdieu, 1993b), but on the other, this autonomy is relative, i.e., they stand in a relationship with each other. The concrete events in a course, its specific social structure, its specific practice, and its underlying social logic are never determined by the field of adult education, but are, of course, pre-structured by it. At the same time, the principally contingent social practice of each individual course within the field will, in sum, also decisively shape the field of adult education. In the following sections, the level of adult education courses will be focused on and only later, the perspective will be broadened again to other levels of aggregation. Therefore, it is necessary to clarify the nature of adult education course research.

Systematically, course research in adult education can be understood as a specific form of research on (classroom) teaching / instruction in educational science (Herrle, 2008). It is focused on (empirically) investigating how the social interaction in the classroom is connected to a) teaching and b) learning processes. However, while school pedagogical research focuses on the school classroom, adult education research addresses the course as an institutionalised form of teaching/learning in the field. All forms of organised education attempt to give the principal contingency of human learning processes a stabilising framework and thus structurally increase their probability of success. In contrast to schools, however, adult education is not a compulsory institution and therefore formal participation in a course, and the type and intensity of practical participation are determined by the comprehensive voluntariness of learning in adulthood. This, however, makes the question even more relevant as to which course features support such continuity and stability. Matthias Herrle (2008) names four central structuring dimensions:

A course is oriented towards working on a specific topic. Usually, this happens explicitly through its announcement in the providers’ programme; typically, the title of a course foregrounds the topic that is being worked on there. This is sometimes only loosely coupled with a specific learning objective, which is often only made explicit if it can be formally determined (e.g., in language courses). For the decision to participate, the topic forms an important anchor, shaping the expectations of future participants and thus already has a pre-structuring effect on course practices. Of course, this ‘official’ topic only offers a rough framework within which, and beyond which, topics are then practically negotiated and developed in the course. Adult education must always maintain a high degree of thematic flexibility due to its orientation towards the participants’ needs. Nevertheless, the reference to a topic-based interaction is the first important feature that distinguishes social interaction in the form of a course from other forms of interaction (e.g., a structurally athematic interaction among friends).

A course is generally equipped with comparatively clear membership rules. Due to their integration into organised adult education, only those who have registered, paid their fee, and are then present on the course will be considered participants. In contrast to other forms of interaction, it would at least be unusual to bring acquaintances along now and then. While someone may choose to drop out at any time, joining later is usually more complicated. Sometimes, participant lists are kept in order to comply with organisational logic. The role of the participant is defined in distinction from the complementary role of the teacher. Even if the concrete form of this role varies greatly, the initial expectation is usually that the teacher has a leadership function, which involves making decisions, or at least suggestions, about the content and didactics for the course, e.g., by presenting a course syllabus, proposing methods and working styles, etc. The teacher also has a mediating role between the course and the provider organisation, which includes certain administrative tasks. Most significantly, however, this role differentiation is also linked to a basic expectation by which the teaching situation is defined: the teacher teaches, and the participants learn.

A course takes place in a specific spatial setting. This means that it is happening in a specific place (e.g., Room 205 of the local Adult Education Centre) and that it is also spatially demarcated from the outside world (everything outside Room 205, like one’s workplace, the café across the street, or the hallway). This space is to be conceived as a social space that is fabricated in social practices by the participating bodies and artefacts such as tables and chairs, blackboard and beamer, etc. These artefacts make this a pedagogical space in reference to the specific historical socio-cultural practices that produced it. Even online courses take place in a virtual location and are characterised by a certain spatiality. The fact that courses take place in a specific place, distinguished from other places where other things take place, is important for stabilizing the pedagogical interaction.

A course is a temporal entity. Courses begin and end, thus they have a duration (that may be connected to organisational planning rhythms and superordinate time institutions, such as a semester). Within this duration, they have a certain number of lessons, which in turn usually have a fixed duration (e.g., 45 minutes). They (usually) take place in a certain rhythm (e.g., weekly) and at fixed, mostly also recurring times (e.g., every Tuesday at 6.30 p.m.). Through these basic time structures, the form of the course thus makes pedagogical interaction projectable and expectable. Although these time-related aspects initially ‘only’ refer to clock time, they are also relevant for our further analysis as they pre-structure the practical production of a specific temporality in the course.

On this basis, we can now describe courses in adult education as topic-focused, spatio-temporally bound interactions between teacher(s) and participants. These basic characteristics make courses a suitable empirical access point for research on temporality of the field. Nevertheless, we must always be aware of the fact that such institutionalised demarcations in the field will by no means be identical to the demarcations we draw as researchers. Especially from a praxeological perspective, we must beware of naturalising the field and always remember its constructional character (Neumann, 2012). The definition of what we analyse as a field and ‘where’ we may be able to witness its practices or get in touch with its agents will only gradually become clear during the research process. Initially, supposedly clear boundaries can become blurred and analytically untenable. To give just one example, if we imprudently equate the beginning and the end of a course with the dates given in the course description, we will be surprised when we find out in our empirical investigation that the teacher and the course participants have been doing courses together for years.

Practice theory, field analysis, and ethnography

For the examination of time, this paper first created the conceptual basis by means of Bourdieu's praxeology. In particular, his theory of social fields plays a central role by enabling us to focus on the specific temporality of a particular field of adult education. Five analytical levels were proposed on which analyses can principally start. The level of the adult education course was discussed in more detail and conceptually specified, because this level will also be the focus in subsequent sections. For the question of how an investigation of temporality in adult education courses on this conceptual basis should take shape, it is necessary to address the research methodological realization. For this purpose, an ethnographic approach will be discussed as being particularly compatible with a praxeological theoretical basis.

Despite being one of the most prominent sociologists, Pierre Bourdieu was originally a philosopher and had not gone through extensive training in research methods. However, his turn to sociology was closely related to being practically involved in empirical research (especially with ethnographic methods) during his time in Algeria. Due to the special social conditions and transformations he witnessed there, Bourdieu saw Algeria as a huge sociological laboratory (Schultheis, 2007), where he had the opportunity to explore a variety of methodological approaches, including quantitative methods, participant observation, interviews, and photography. The data sources were the ‘classics’ of cultural anthropology; material artefacts, like traditional weavings or peasant potteries, as well as aphorisms, poems, and collected wisdom (Schultheis, 2007). He also showed a lively interest in time-related aspects of the Kabyle culture, such as daily time structures and annual rhythms (Bourdieu, 1977).

Bourdieu’s experiences in Algeria were an important basis for further theory development, and they also had an important influence on practice-theoretical methodologies. Although a wide range of methodological approaches is used in practice-theoretical empirical research today, ethnography serves as a particularly influential foundation and serves as a methodological bracket around this diversity. A rejection of certain methods is sometimes expressed too pointedly in praxeological discourse; while the statement “that studying practices through surveys or interviews alone is unacceptable” (Nicolini, 2012, p. 217) is strictly speaking correct, it is all too easy to overlook the important limitation of alone or the emphasis on practices.

Such ex-post data may be particularly helpful, especially for an analysis of social fields incorporating the three elements unfolded above. Historical sources can be used for a genealogy of the field, quantitative data from surveys may serve to analyse the positions and their relational structure forming the field, and qualitative interviews may open up the subjective reconstructions of the agents within the field (Schwarz, 2016, 2019a). The direct observation of social practices should unquestionably be a central, but by no means the only, empirical approach in a practice theoretical methodology toolkit. As practice theory places social practice in a reciprocal reproductive relation to social fields and habitus, the analysis of structures, both objectified and subjectified, is of the utmost importance, and these structures cannot be adequately analysed through observational data alone.

What is important above all is “an internally coherent approach where ontological assumptions (…) and methodological choices (…) work together” (Nicolini, 2012, p. 217). Ethnography not only fulfils this criterion, but also offers an approach that is methodologically integrative, if one takes its methodological opportunism (Breidenstein, Hirschauer, Kalthoff, & Nieswand, 2020) seriously:

It is one of the strengths of ethnographic fieldwork, indeed, that it is not tied to any one method of research or one form of data. (…) The social world is enacted and represented through multiple forms and multiple cultural codes. Social organisation is realised in complex ways that depend on multiple forms, conventions and principles. Social and cultural orderliness is made with symbolic means, with material artefacts, with linguistic repertoires, through spatial and temporal frames of reference. The proper conduct of ethnographic work, therefore, needs to do justice to those modalities of social and cultural organisation. (Atkinson, 2015, pp. 37-38)

Ethnographic course research on temporalities

In accordance with these considerations, a method-integrative ethnographic approach to the temporality of adult education fields will be developed in this section. At its core, it will describe the triangulation of participant observations with narrative participant interviews and the analysis of documents and artefacts in the form of course ethnographies. For this purpose, particular reference is made to methodological reflections from our current research project on “Time and Learning in Adulthood”1 where we ask about the differences of temporalities in different course formats within non-formal adult education: how do week-long block courses differ from weekly, daily, or evening courses, and from highly flexible online courses? With reference to this project context as a concrete example, the practice-theoretical and field-analytical socio-theoretical perspective will be connected to the methodological procedure of ethnographic course research and to the research interest in temporalities. Unfortunately, it is beyond the scope of this paper to present concrete empirical cases and their analyses, so we will only refer here to the already published results of a preliminary study (Schwarz, Hassinger, & Schmidt-Lauff, 2020).

To narrow down the question of what we actually observe in an adult education course when we want to observe its temporality, we will build on the concept developed by Vibeke K. Scheller (2020) in her “tempography” (a term that was coined by Eviatar Zerubavel (1979) for organisational ethnographies on time). During her investigation of the social practices in a cardiac day unit, she develops a threefold structure that will be used as a heuristic in this paper:

Firstly, in line with the practice-theoretical importance of materiality and the ethnographic attention paid to artefacts, objects of time form a first anchor category. Most obviously, we can observe them in courses as clocks that are perhaps the most widespread ‘object of time’. Almost every seminar room will be equipped with one, but perhaps also the teacher and the participants will wear clocks or use their mobile phones to check the time. In fact, many other technical / media devices used in a course will show the time. The clock itself brings a specific time into the course simply by being there, and by asking if and how the clock is used in practice, and how it is referred to implicitly or explicitly (e.g., who casts a quite blatant glance at it and in which situations), can tell us something about how ‘objective time’ is brought into communicative or practical play within courses and what symbolic dimension attaches itself to these strategies. Of course, the clock is only one time object among many; another ‘classic’ object, especially in ethnographic time research, is the calendar. In courses, too, for example, a common calendar can demand shared time structures, or all participants can get out their calendars to coordinate a common date. Closely related and important in most adult education courses is the course plan, which can objectify the temporal predetermination of the course events, be it exact didactic planning or demonstrative pedagogical flexibility.

Secondly, focusing the researcher’s gaze on temporal work means examining the practical and pre-consciously strategic use of time in adult education courses. In the first place, there is certainly the question of how the synchronisation between the time of teaching and the time of learning takes place, and how its necessary situational asynchronisation is countered with socially harmonised synchronisation work (Berdelmann, 2010). Furthermore, we must examine how “one’s ‘own’, proper time” (Nowotny, 1992, p. 444) is negotiated with all other course members, how a common time order is established, and how deviations are socially regulated (e.g., lateness, absenteeism etc.). How can common rhythms and common speeds that are conducive to learning be established and regulated situationally within the course? These forms of temporal work sometimes occur in courses as explicit negotiation processes (e.g., ’I would like to finish the topic, can we do five minutes longer?’); in many cases, this work must be done in the form of material, body-related and symbolic practices (e.g., the noticeably restless manner of sitting on a chair).

Lastly, attention must be paid to trajectories; although the term, following the work of Glaser and Strauss (1965), may initially be strongly associated with individual process trajectories in the context of illness and dying, the perspective associated with this term has also been discussed from a praxeological perspective and in the context of pedagogical issues (such as transition research) (Burger & Elven, 2016; Schäffter, 2015; Schwarz, Teichmann, & Weber, 2015). For the study of adult education courses, the term makes it possible to focus on course participation as a process. This can then be linked to the question of the extent to which a learning process is also carried out beyond the course. However, beyond the individual trajectories of the course participants, the trajectory of the course itself must also be examined; it is then also about a certain (self-)narrative about the course as a process, based on which are the social constructions of starting and ending points, of progress logics, and of acceleration and deceleration moments.

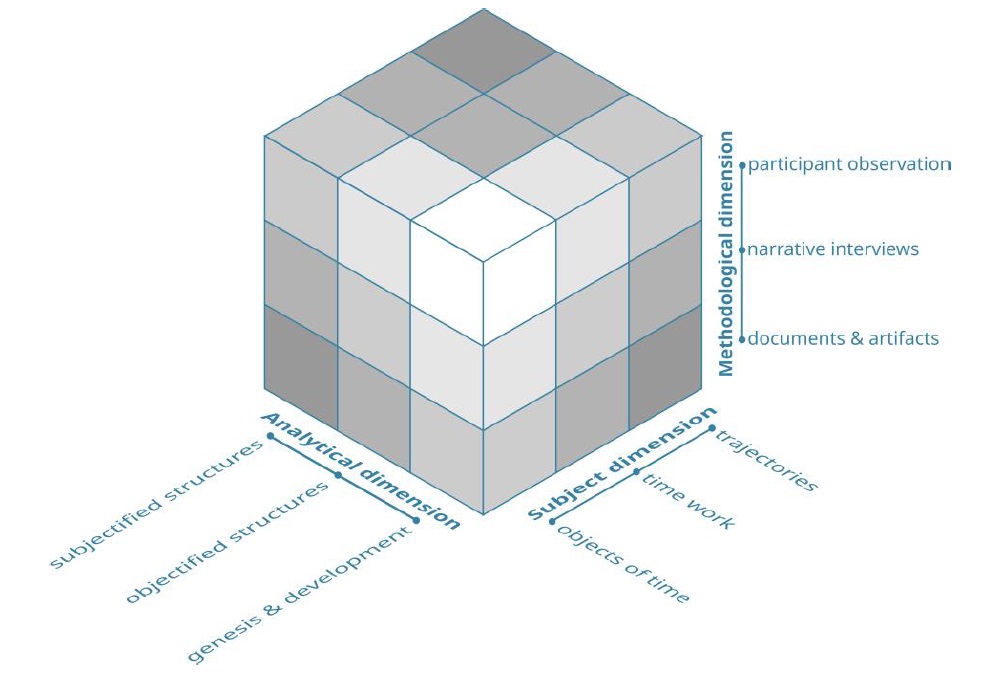

With this tempographic heuristic, the last element is now available to provide a three-dimensional interlacing of perspectives for the analysis of temporalities in adult education courses (figure 1). It may appear at first glance that there is duplication between the three perspectives (e.g., between time objects and ‘documents/artefacts’), but it is important to emphasise that three independent dimensions of investigation are given here, so that each of the twenty-seven entanglements (i.e., each individual cube) establishes its own perspective. For example, the course syllabus can be considered as an object of time that can be examined on the basis of participant observation in its role in the struggles with objectified structures of dealing with time in the course.

Participant Observation in the course

The core approach in a course ethnography is participant observation within the course. In contrast to other classic fields of ethnographic investigation, field access is comparatively easy because adult education courses aim at accessibility for everyone and thus, researchers can ‘officially’ register as a participant for the course. Nevertheless, in the context of our project, we first contacted the head of a department or of the institution to solicit support for our research project and to inquire which courses in a certain area they could recommend to us. This also enabled us to contact the teachers before the start of the event and to prepare them for our presence on the course. The participants were informed and asked for their consent in the first lesson of the course through a brief introduction of our research purpose and our role as regular participants who will also be observing what’s going on.

To take on this ambiguous role is comparatively easy in course research because the participant role is commonly institutionalised as a ‘semi-passive’ role anyway; even in adult education, the student job (Breidenstein, 2006) initially consists of being present and attentive while the teacher takes on the active part. This enables the researchers to focus on the observer role in these phases. Active participation is often explicitly demanded, goal-oriented, and limited in time (e.g., through a question from the teacher, in group work, etc.) so that it is also obvious when to switch to active participation. Against this background, it is of course important to ensure that the researchers can participate actively, and avoid courses that require a certain basic level in a foreign language that the researcher does not have, for example. More generally, in ethnographic course research, a credible interest in the topic is perhaps the most important basis for establishing rapport with other participants and teachers.

Once we have access to the field, and one’s role in the course and rapport with the participants has been established, we can focus on the question how and what to observe. As to the how, it is important to note that it is not about visual observation in the narrower sense, but rather the researcher must use all the senses and, not least, ‘le sens practique’ (Bourdieu’s concept of a sense for the logic of practice) (Breidenstein et al., 2020). Ultimately, from a praxeological perspective, it is important to observe not only the social practice within the course but also how we relate to this practice in terms of ‘participant objectivation’ (Bourdieu, 2003; see also Neumann, 2012).

Narrative interviews with participants

In the context of ethnographic course research, one naturally enters into conversation with course members, both the teacher and the participants, in various ways, especially before the beginning and after the end of courses, as well as during breaks. These informal conversations can be of great importance to the research process, as they are significant for establishing rapport with the participants, being accepted (or not) as an observing participant, and can provide important background information on practices observed, without which an adequate understanding might not have been possible.

However, from these informal conversations explicit interviews must be distinguished (Breidenstein et al., 2020, pp. 93-99). The latter are used within ethnographic approaches in all the forms that are common in social research, are explicitly arranged with the interviewees, and usually take place outside the primary observation context. In our project, we leave it up to the participants to choose the time and place, so that the interviews can sometimes take place in a closer context (e.g., after the course in a café near the institution, or in the evening during a block week). When we talk about our research project at the beginning of the course, we refer to the fact that we would like to interview some participants, so these requests come as no surprise. After some time in the course, there is an open enquiry among the participants, but we also directly ask individual participants from whom we expect interesting time-related perspectives, due to her being a single mother, for example, or due to their role in the course.

The narrative interview here, in the concretization of Schütze's (1983) autobiographical narrative interview, aims to achieve life history narratives in an open conversational format, relying on “narrative constraints” (Schütze, 2016, p. 114) in accomplishing the biographical narrative. The widespread use of this methodological approach in educational biographical research has stimulated intensive methodological reflection, some of which systematically addresses aspects of temporality in biographical narratives (Schmidt-Lauff & Hassinger, 2023) - which can, however, only be referred to here, since we focus on the praxeological approach. For a course ethnography of pedagogical temporalities, the narrative interview is of particular interest, especially due to three specific features.

1. The educational biographical embedding of course attendance is relevant because previous experiences in formal and non-formal education shape the concrete practices in the course.

2. It is extremely important to learn more about the embedding of course attendance in the everyday life of the participants, both in terms of the practical feasibility of course attendance and its fit with dispositions for time perception and time use.

3. The learning experiences of the interviewees over the course are significant for the analysis of connections between temporalities and learning. From a practice theoretical perspective, we must expect the interviewees to have limited reflexive access to their earlier educational experiences, habituated time-related dispositions, and current learning processes in the course, while narratives can nevertheless open up an analytical approach (see below).

Documents and Artefacts

The study of documents and artefacts describes a third important approach to the temporality of courses in adult education. Since we have already classified courses as a form of organised adult education, the role of documents is almost inevitable. For it is precisely within organisations - or, rather in social practices of organising - that written communication between organisational members, the recording and documentation of the organisational past, and the written formalisation of processes and procedures play an important role. From this point of view, documents are not mere containers for text; they must be regarded as artefacts, or even as standardised artefacts (Wolff, 2012), as something made by the culture to be studied, which has emerged from concrete practices and which is at the same time connected within this culture with certain modes of use, i.e., is intended to ensure the production of specific practices.

Although the use of documents can also come into view in participant observation, the observed practice can sometimes only be adequately understood through an in-depth examination of the documents itself content, form, materiality, and the visual qualities, all of which play an important role. Time can be an explicit object of documents, e.g., when attendance is recorded on an attendance list. However, it can also be indirectly linked to documents when, for example, a text is to be worked through by the participants in a given amount of time, or an assignment sheet is to be completed in the course, it is essential for the analysis to gain a deeper impression of the temporality associated with this task, through an analysis of the document, in order to relate this to certain observations, such as ‘almost all participants are still intensively writing when the instructor announces the end of the working time’, or to impressions of the participants (‘the worksheets always stressed me out’).

Widening the scope: From courses to organisations and the adult education field

While the methodology for an analysis of temporalities in adult education fields was initially developed through the consideration of course ethnographies, a necessarily brief outlook on the inclusion of other field levels should be provided. The conceptualisation carried out here can be largely transferred to the examination of adult education providers, i.e., to organisations as fields. Adjustments become relevant here, especially in the context of concrete methodological implementation; for example, we can assume that the interactions on the course, which can usually be overseen by the participant/observer, do not happen in such a compact way in an organisation. Here, it becomes necessary to focus on interaction situations that are particularly relevant (e.g., joint meetings of all departments for programme planning) and to include mobile forms of observation, following or ‘shadowing’ key agents (Czarniawska, 2018). Of course, the analysis of documents becomes even more important, especially when the organisational past is examined from a historical perspective. In terms of field analysis, greater weight will be given to the question of decided positions within the organisation and their respective power relations to each other. Ultimately, this is also accompanied by the question of the relevant capitals, which may be linked to questions about time structures. With a view to temporal work, struggles for power of the definition of doxic temporal orders will presumably emerge even more clearly than in the course interaction.

If we look at the field of adult education, its demarcation from others becomes a challenging problem. The basic question that can be pursued at this level is; how does the temporality of adult education differ from the temporalities of other fields, such as that of higher education, and how does it relate to the field of education as a whole, or even to the field of the economy? These questions can only be addressed in a comparative way and can only be tackled against the background of a long-term research programme. The empirical research on the temporality of adult education courses and organisations are already a systematic part of such a comparative-integrative project. Methodologically, however, the inclusion of quantitative procedures is increasingly being considered, which are more capable of taking a bird’s eye view of the field across its entire range. With appropriate methodological integration, and with procedures such as correspondence analysis, such an approach can be used as a complement to the methodology presented here (Schwarz, 2019a).

Discussion and Outlook

This article opened with a discussion of temporality in the field of adult education that is grounded in practice theory and draws on Bourdieu’s field analysis. This perspective has been linked to a tempographic heuristic, along which observation objects that can be concretised as objects of time, temporal work, and trajectories. With reference to participant observation, narrative interviews, and the analysis of documents and artefacts as its three core approaches, the outlines of ethnographic course research on temporality in the field of adult education were worked out. Lastly, the review was extended to include a necessarily succinct discussion of the application of this methodology to provider organisations and, finally, to the field of adult education itself, thus at the same time outlining the contours of a more comprehensive research programme. The approach presented here may stimulate an intensified empirical examination of the phenomenon of time in adult education research and develop relevance for the practice of adult education.

For this purpose, the conceptual foundation in Bourdieu's praxeology is relevant because it makes it possible to locate time not only either in the realm of subjective sensation, perception and action or in the institutionalized social structures, but in their interplay. For adult education, this means an analytical reconciliation of perspectives that are far too often in opposition, or at least at a distance from each other, namely one focused on the adult learning of the subjects and one focused on the structures of adult education. The praxeological perspective enables, indeed requires, the unification of both perspectives in the empirical engagement with social reality. Moreover, it emphasizes that it is only in this interplay that specific temporalities emerge, thus supporting not only a relational but also a processual conception of adult education. This conceptual facility is supported by the methodological focus on an ethnographic approach that combines direct observation of adult education practice with an analysis of its artefacts and the interrogation of its central agents. This allows for a multi-methodological and multi-perspective illumination of the temporality of adult educational fields, which can fulfil the theoretically set claim. Furthermore, the integration of other methodological approaches, especially quantitative analyses, into the overarching ethnographic research logic is possible.

The research program formulated here is promising for further research on time in adult education, while the conceptual and methodological framework also offers the possibility of enriching the practice of adult education, especially at the course level, which is the focus here, and also at the organizational level of adult education. Instruments and techniques of professional self-reflection can be derived from this approach, which can substantiate a time-sensitive professional practice (Schmidt-Lauff & Bergamini, 2017). Unfortunately, manifold questions could not be addressed within this contribution; at least three of these should be considered as an outlook for further developments.

First, any detailed statement on questions of analysis and interpretation has been avoided so far. This is by no means unusual in ethnographic research (Breidenstein et al., 2020, p. 127) and is probably due, on the one hand, to the still relatively dominant position of grounded theory (especially in Anglo-American discourse) and, on the other, to the general concern about over-methodisation: “ethnographic analysis is never achieved or exhausted by the application of a rule-bound set of procedures” (Atkinson, 2015, p. 66). In the case of the present article, however, quite the opposite is true; in our current project, we are gaining experience with the application of such a ruleset by applying analytical strategies and techniques from the Documentary Method (Bohnsack, Pfaff, & Weller, 2010). This methodology is based on practice-based theoretical perspectives that especially emphasise the role of atheoretical knowledge in the form of orientation frames that are linked to the social conditions of their acquisition in milieu-bound practice. It was developed especially for the interpretation of group discussions, but today it is also used with narrative interviews and videography. While participant observation was discussed early on, it has received little attention and methodological development in recent years. We will only be able to answer the question of how exactly this quite differentiated, rule-based analytical system can be used in a generally ethnographic study once our interpretation work has been completed.

Second, although it has already been noted that online courses are also being studied within the framework of our research project, the special methodological requirements associated with this have not yet been addressed. In the first place, the question arises of what participant observation in an online course can observe and is directly confronted with the problem of the spatial, as well as temporal, disjuncture of interaction situations and the technology-supported dissolution of teaching. Within the project, we focus primarily on those forms of digital education that still have the character of a course, i.e., in which a defined group of participants works on a specific topic at a given (now virtual) location and at defined (albeit often individualised and flexibilised) times, so we are still concerned with organised and socially coordinated forms of online learning. We also decided to focus our participant observation on the virtual space, i.e., the interactions observable on a learning platform, in social media, and in video conferences. We primarily access the concrete situation of the learners through the narrative participant interviews, which we extend by asking them to keep a learning diary over a period of two weeks so that we can address the temporal organisation and embedding of the learning activities in everyday life in the interview on the basis of this self-observation. This also reveals the necessity of a significantly more extensive and complex analysis of documents within online courses (Wein, 2020).

Third, the researchers have so far been addressed as participants and observers, and less as learners. As mentioned earlier, with regard to the experience of temporality in the course, the ability of the researchers to perceive is of utmost importance, but in the context of ethnographic course research on temporality, the process of learning also represents an essential point of reference for the analysis. On the one hand, this can be reconstructed through the narrative participant interviews, but at this point, it is obvious to also include more autoethnographic perspectives on the learning process of the researchers. “Body & Soul” (Wacquant, 2006) shows how one’s own learning process, here as the manifest training of the body in the boxing ring (where time also plays a significant role), can become part of a sociologically reflected observation. At the same time, however, it must be taken into account that the researchers - regardless of how much they are affected by the course topic and how immersive the learning might be - are still only partial participants. It is important to remember that

the ethnographer who seeks to ‘get close to’ others usually does not become one of these others. As long as, and to the extent that, he retains commitment to the exogenous project of studying or understanding the lives of others, as opposed to the indigenous project of simply living a life in one way or another, he stays at least a partial stranger to their worlds. (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 2011, p. 43)