Introduction

The protection of public health according to its constitutional understanding as a task of the State (articles 9 and 64 of the Portuguese Constitution) shows that we are faced with a topic shared by many areas of law. However, perhaps no other legal branch has been affected by the current pandemics as Public Law and especially Constitutional Law. This perception is a combined result of two phenomena: on the one hand, the concerns of public powers are now focused on the implementation of the right to health; on the other hand, the mechanisms adopted to fight Covid-19 involved exceptional provisions that affected significantly other fundamental rights. As in Germany, Portugal is currently under a Constitutional (and administrative) law of exception.

Rule of law, Rechtsstaat and Etat de droit are key concepts of our constitutionalism, based on the protection of fundamental rights. The main problem that the theories of the law of the exception must solve is the balance or the dialectics between the safeguard of fundamental rights and guarantees, and the government’s urgency to act.

A quick overview on Professor Kaiser’s speech demonstrates that the Constitutional Law as applied is normal times is disabled in dealing with emergencies and severe crisis like pandemics, but this doesn’t mean that normal Constitutional Law has not have the resources to deal with these situations. The praxis (and the Portuguese experience) reveals, on its turn, that perhaps a specific Constitutional Law of the exception is not skilled enough to tackle with the consequences of a long-term crisis.

For instance, the seven traditional topoi Professor Kaiser identifies as main theses in the constitutional law of exception reveal the deep consequences that crises bring to the core of “constitutionalism as mindset” (if we want to invoke Koskenniemmi and a particular Kantian vision of constitutionalism): separation and interdependency of powers, protection of fundamental rights and, in general, juridicity (Rechtsmässigkeit) of public action.

Commentary

I will not be able (I would not dare) to commentate all the topics chosen by Professor Kaiser, so I will focus on five ideas.

1. First of all, and with the purpose of stressing the differences between the Portuguese and the German systems already pointed out by Professor Kaiser, I will emphasize that the experience of the Weimar Republic (based on Carl Schmitt’s doctrine) and especially the experience of the Nazi abuse of article 48 of the Constitution highlights the dangers of a constitutional or legal framework that promotes the empowerment of the President, allowing him to temporarily suspend fundamental rights, without a real concurrence of the other constitutional organs. This is why the Portuguese system actively involves the Parliament in this process. In fact, the state of emergency supposes not only an agreement between the three main constitutional political institutions - the President, the Government, and Parliament, within a system of checks and balances -, but also the parliamentary control over its execution.

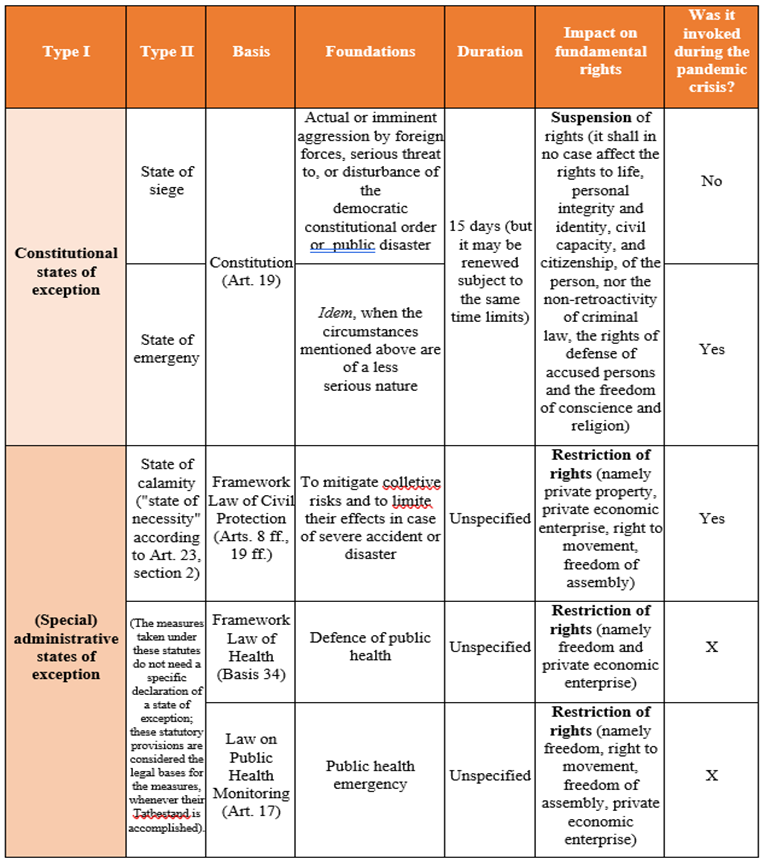

2. Second, and whenever the legal systems recognize the essentiality of the opposition between the so-called law of normality and the law of the exception, I will underline the importance of codifying this law of the exception or this kind of constitutional state of necessity - instead of leaving the problem to interpretative solutions mainly reached outside de Constitution, as it is traditional, for instance, in Switzerland. However, the Portuguese constitutional design of the state of emergency does raise serious doubts: for instance, it is conceived for a short period time (15 days), but it may from time to time be renewed subject to the same time limits. Experience has already demonstrated that the pandemics is here to stay and currently we are assisting to successive renewals of the state of emergency - clearly revealing its disability to deal with pandemic crises. Nevertheless, the counter-argumentation remains equally strong: the limited validity of the state of emergency offers the possibility of a strong political and constitutional monitoring, since there is always a parliamentary control over the subsequent renewals of the state of emergency. In addition, the Presidential decree of declaration of the state of emergency is itself an act whose constitutionality can be reviewed by the Constitutional Court.

3. My third remark will underline a common topic: the absence of a healthy emergency clause both in the Portuguese and in the German constitutional texts (both in the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic and in the Grundgesetz). However, differently from Germany, we have a general provision to deal with a “public disaster” and this has been the constitutional basis of the President’s decrees among us. But the question remains: what can or shall be addressed as a public disaster? That is a topic that will demand a subsequent reflection, in order to interpretatively densify this wide concept.

4. Professor Kaiser told us about the introduction of a new state of emergency into German law: the “epidemic emergency of national concern” and its relevance concerning the Federal Ministry of Health’s competence to issue executive rules. Portugal faces an analogous problem, but the framework (even the constitutional framework) is rather different from the German one. In Portugal, under normal conditions, Government has already competence to enact independent executive rules. Those independent regulations may even be issued under Article 199, section g), of the Portuguese Constitution. According to this disposition, the Government is competent to perform all the activities and make all the arrangements necessary to promote economic and social development and to meet community needs. Nevertheless, this power has limits - one of them concerns precisely the matters related to rights, freedoms and guarantees.

But this topic attests the important role played by the Government (acting within its administrative powers) under normal circumstances, a role traditionally increased in times of exceptionality. Not only the Government has the responsibility to execute the decree of the President that declares the state of emergency, but also the insufficiencies revealed by the state of emergency were tackled by administrative legal instruments: states of alert and contingency and the (special) administrative state of exception consisting of the “state of calamity” - all provisions that strengthen the central role of the Government. In addition, in the event of public health crises, the Portuguese law on Public Health Monitoring attributes to the Ministry of Health a competence to enact executive rules, as well as any exception measures involving the restriction, suspension or closure of economic activities, the separation from healthy people, means of transportation or merchandises, in order to deal the dissemination of the infection or contamination.

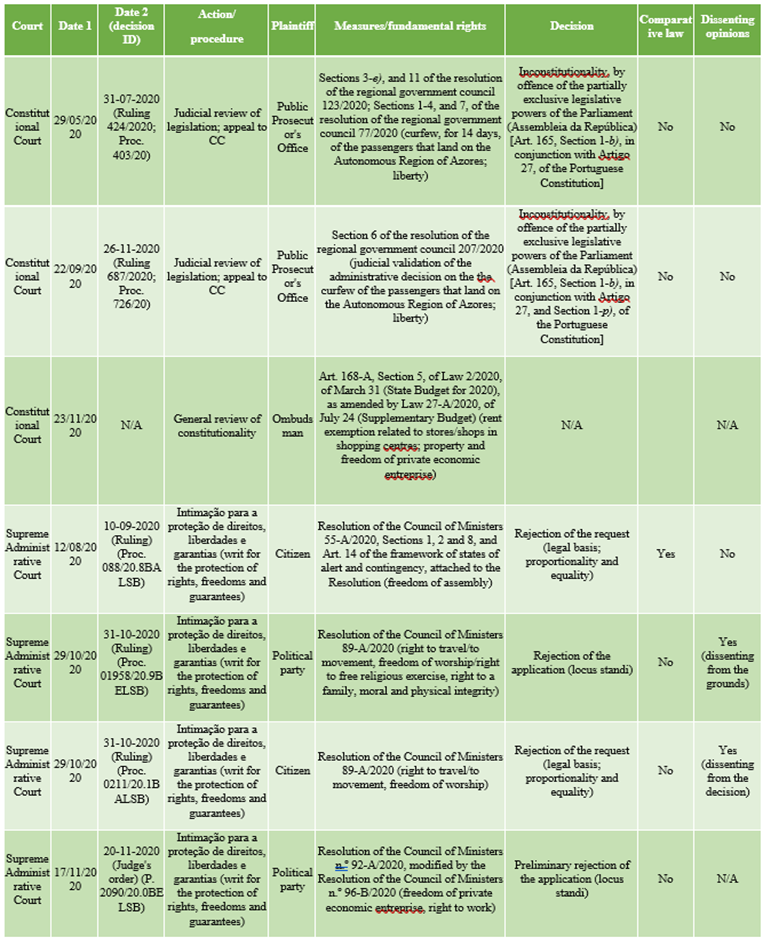

5. At last, and as Professor Kaiser stressed already, under exceptional circumstances, it is important that the rule of law really functions. Despite believing that the rule of law is working as it should (also in Portugal), it cannot be concealed that there are few judicial actions on pandemic measures, as it can be concluded from the following table:

Table 2: Jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court and the Administrative Supreme Court updated to 17.12.2020

A preliminary analysis of this data allows some reflections:

From a comparative law perspective (Professor Kaiser told us about the impressive number of over 1000 published administrative and constitutional court decisions on pandemic measures in Germany!), we do not have a great number of decisions. But this does not mean that the Portuguese measures are less problematic or do not raise constitutionality or legality questions - as we can attest by reading the dissenting opinions.

The Constitutional Court lacks powers to rule in proceedings specially designed to protect fundamental rights against public authorities (like amparo or Verfassungsbeschwerde). The Constitution remained not indifferent to this problem: Article 20, para. 5, added by the 1997 Amendment, established that in order to defend personal rights, liberties and guarantees, the law shall provide citizens with legal procedures that are characterized by swiftness and priority, so that there is effective and timely protection against threats or violations of these rights. In 2002 the requirement has been met by the creation of the writ for the protection of rights, freedoms and guarantees within the jurisdiction of administrative courts, a mechanism that aims at condemning administrative entities to adopt a conduct which is indispensable to the exercise, in good time, of a right, freedom and guarantee. Concerning the pandemic measures, the above-mentioned absence of powers of the Constitutional Court regarding the appreciation of concrete decisions of inferior courts has the effect that the power to protect fundamental rights is shared with the Supreme Administrative Court (the latter playing an outstanding role on this matter).

The decision of the proceedings was fast, and therefore fulfilled the swiftness and priority demanded by the Constitution and the substantive exigencies of the rule of law.

The principles of proportionality and equality were taken as standards of review, revealing, in some measure, the difficulties and the weaknesses of the traditional understandings of such principles.

The Courts begin to appeal to Comparative Constitutional Law, which expands the horizons of the solutions to concrete problems and enables the enlargement of the testing ground of the plausibility of the argumentation underlying the rulings. However, if the dialogue between national, foreign and international jurisdictions may be considered fruitful, it shall not be an argument (or even a juridical basis) to modify the core of the fundamental principles that rule Public Administration - like the principle of legality. Although law is performative and argumentative, an abstract appeal to European or International law shall not replace the liaison between the rule of law (in the sense of Rechtsstaat) and the democratic principle - which is the punctum crucis of the exigency of an accurate and precise legal basis for the administrative action.

Conclusion

The Portuguese model reveals a combination between the restriction and the suspension models, trying to achieve the balance between emergency measures and the protection of fundamental rights, within a constitutional system shaped on the interdependency of powers. The important role played by the Government demands a severe control (hard-look review) on the existence of a legal (parliamentary) basis of the administrative measures (specifically, executive rules) on rights, freedoms and guarantees. The absence of a systematic framework to deal with a pandemic crisis and the problems related to the protection of fundamental rights clearly demonstrate that we are again back facing the very core of constitutionalism.