Introduction

Multi-screen media consumption and practices are clearly rooted in society, especially amongst the current generation of young people, and the phenomenon is predicted to become more widespread. This is the scenario that some authors describe as a “(new) media ecology” (Scolari & Fraticelli, 2017), others as a “new media environment” with its own features that are different to those of the past (Jenkins et al., 2013; Press & Williams, 2010), and others as “the media life of audiences” (Deuze, 2011; Manovich, 2009), who live “across” different media (Lomborg & Mortensen, 2017).

Whatever description we might refer to, this online environment is the natural one for the so-called “generation Z”, that is, the current adolescents and young people. Following the digital natives (Prensky, 2001) or millennials (generation Y), who represent a consumer generation “who exhibits a ‘networked hypersociality’ and a ‘participatory exhibitionism’” (Serazio, 2013, p. 599), the current generation Z can be considered the first true digital generation, since it refers to individuals born between 1995 and 2012, and who have grown up “with a highly sophisticated media and computer environment” (Schroer, 2008, p. 9). Fernández-Cruz and Fernández-Díaz (2016) summarise the main characteristics of generation Z as the following: “1) expert understanding of technology; 2) multi-taskers; 3) socially open through the use of technologies; 4) fast and impatient; 5) interactive; and 6) resilient” (p. 98).

Thus, current digital media, the so-called social media, including YouTube, play an important role in the very conceptualisation of the current youth identity and youth culture, as well as being a socialisation and learning tool for the youngest, as traditional media have been (Aran-Ramspott et al., 2018). In particular, recent data confirm the central role YouTube plays in the media life of young people in the west. For example, according to the Pew Research Center (Anderson et al., 2018), YouTube is the most popular platform among US teenagers, since 85% of them say they use it. More than 80% of US parents let their children watch content on YouTube, while children’s content and videos featuring children have become more and more popular (van Kessel, 2019). According to Ofcom (2019), 89% of UK tweens use YouTube, especially to watch funny videos or pranks and music content. Moreover, nearly 50% of them prefer watching content on YouTube than on television. In Spain, YouTube is the most highly rated network after WhatsApp, and its usage is growing among the Spanish population (IAB Spain, 2019). Around 70% of Spanish teens (14-17 years old) prefer YouTube (after Facebook) among social media (Pérez-Torres et al., 2018, p. 62). In a multinational study carried out in Spain, Portugal and Italy, teenagers rated “watching YouTube channels” above other media practices and attitudes (Pereira et al., 2018).

Papacharissi (2015) puts forward the idea that all media (both the so-called “old” or traditional mass media and the “new” or internet-based media) are social, because of their “social character ( … ) as they develop within the context of societies and everyday life” (p. 1). Therefore, it is of great interest to analyse how YouTube, the largest social media in the world together with Facebook, with almost 2.000.000 monthly users in 2019 (YouTube, n.d.), is actually developing its social potential, especially in young people’s everyday life. The three main characteristics that are fundamental in defining this “social” nature of some digital media platforms, according to Bechman and Lomborg (2013), and which are very relevant in the case of YouTube, are:

Communication is de-institutionalized: social media allow users to contribute to and filter the content that they consider relevant, sharing it with audiences of their choice.

Users of these sites are intrinsically considered as producers of different kinds of content, depending on the nature of the sites (photographs, short messages, video, audio, text files, etc.).

Communication is interactive and networked, with users constantly shifting from production to reception modes, as they wish.

Traditional media, such as television, can be attributed several social functions, such as entertainment, narrative, and socialisation functions, which include personal identity building, learning about reality, sharing and commenting with the peer group, and identification with characters, among others (Fedele, 2011). Internet-based media can also carry out these social functions in young people’s everyday life. For instance, adolescents can use YouTube for similar reasons that they watch television, and also as “a channel to express themselves and a space for cultural empowerment” (García-Jiménez et al., 2016, p. 60).

Arthurs et al. (2018) highlight that there is a recent multidisciplinary research field that focuses on YouTube, relating the platform to digital culture and society. Most previous studies have centred on middle and late teenagers (e.g., García-Jiménez et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2018; Pereira et al., 2019; Pires et al., 2019), or university students (e.g., Klobas et al., 2018), and to a much lesser extent on early adolescents, those known as preadolescents or tweens (9 to 13 years old), who are neither children nor adults (Linn, 2005), but “between human being and becoming” (La Rocca & Fedele, 2015, p. 19). Tweens are, in fact, a “transitional age group undergoing deep physical and psychological transformations” (Quelhas-Brito, 2012, p. 580). In this sense, Buckingham et al. (2005) point out that, between middle childhood and early adolescence (that is, 9 and 12 years-old), children are increasingly bringing more general social understandings to bear in their judgment of media. However, it is not until the age of about 11 or 12 that children may begin to speculate about the ideological impact of media, their potential effects or the processes of stereotyping. In addition, as Moreno Hernández (2009, p. 61) points out, it is between the ages of 7 and 12 that the child begins to be more sensitive to the diversity of people’s opinions beyond their immediate environment, by progressively adopting a social perspective, according to Selman’s (1980) theory of social role taking. Therefore, tweens can be especially sensitive to social media content and uses. This paper focuses precisely on this particularly vulnerable segment of the population, preadolescents or tweens, analysing their preferences, practices and uses related to YouTube.

Adolescents’ Uses and Practices Related to Social Media

Pereira et al. (2020) point out that several studies about young people, children and media have been carried out, especially in the last 2 decades, focused on different aspects of young people’s media life. As Subrahmanyam et al. (2015) indicate, research suggests that young people are using digital tools to extend their networks with people they know “in general to connect with friends, as well as to look for support or cultivate emotional links” (p. 118). There is a whole line of research into the self-representation of young people on social media which indicates that the youngest adolescents present a more multifaceted sense of themselves in their profiles (Livingstone, 2008), and in particular that they communicate their personal, social and gender identity through their photos (Salimkhan et al., 2010).

Uses and gratifications theory, in particular, makes it possible to identify users’ motivations for employing social media, since it can allow “the study of this convergent media environment” (Papacharissi, 2008, p. 144). According to this approach (e.g., Katz et al., 1973; Rubin, 2002), audiences are considered active and able to use media to seek different kinds of gratifications or functions, since “individuals select media and content to fulfil felt needs or wants” (Papacharissi, 2008, p. 137). Both this theoretical approach and cultural studies have highlighted the uses, practices, and social functions that audiences give to traditional media, such as television. These include entertainment, emotional experience, knowledge about the world, social learning, identity building, social relationships, socialisation, and relationship with the characters, including parasocial relationships (e.g., Livingstone, 1988; Lull, 1980; McQuail, 1997; McQuail et al., 1972). As for social media, Whiting and Williams (2013) identify 10 uses and gratifications: social interaction, information seeking, passing the time, entertainment, relaxation, communicatory utility, convenience utility, expression of opinion, information sharing, and surveillance/knowledge about others. Igartua and Rodríguez-De-Dios (2016, p. 109) point out that social media enable users to obtain gratifications similar to those already recognized in traditional media, such as those based on content (e.g., information, entertainment), on the experience of using the media (e.g., playing with the technology), and, due to the interactive dimension, markedly social and communicative aspects, such as communicating with friends and extending one’s network of acquaintances (e.g., Bonds-Raacke & Raacke, 2010; Joinson, 2008). Igartua and Rodríguez-De-Dios (2016) propose a motivational model to describe the motives for using Facebook based on seven categories: entertainment, virtual community, maintaining relationships, coolness, companionship, and self-expression.

Specifically in relation to YouTube, Ito et al. (2010) identify three macro-categories of participation genres, which are related to three types of uses: “hanging out” (which can be considered as an erratic use), “messing around” (explorative use) and “geeking out” (expert use).

The “Transmedia Literacy” project, a European study carried out in the same period as the present study, determined five uses that teenagers can make specifically of YouTube: radiophonic (e.g. listening or downloading music), televisual (e.g. watching entertainment content or following YouTubers), social (e.g. commenting or co-viewing), productive (i.e., creating or managing personal content) and educative (e.g. learning something new or solving problems; Pires et al., 2019), including informal learning (Pereira et al., 2019).

In Spain, one of the first studies about young people’s motivations for using social networks was carried out in Andalusia (Colás-Bravo et al., 2013), with a sample similar to that used in our research. That study found no significant differences in the frequency of use of social networks between boys and girls; however, it did note differences in motivations: boys had more emotional motivations, whereas girls had more relational motivations. Another study about adolescents’ media diet, carried out in Catalonia, recognized some mainly relational and socialising functions in information technologies in the lives of adolescents (Fedele et al., 2015), which is more marked in girls. However, another study, carried out in the Basque country, showed the “opposed male/female patterns in the way young people consume, create and diffuse leisure content” (Fernández-de-Arroyabe-Olaortua et al., 2018, p. 61). The authors found that video games were “the central backbone of male consumption and creation” and girls preferred to use social networks (Fernández-de-Arroyabe-Olaortua et al., 2018, p. 61). This study also showed that “creating and sharing audio-visual content does not seem to be a widespread activity among young people” (p. 66), which could be related to a mostly passive use of YouTube among young users, which was pointed out by Pérez-Torres et al. (2018, p. 63).

A more recent ethnographic study on media practices carried out in Madrid with children and preadolescents under 14 years old (de la Fuente-Prieto et al., 2020), revealed that “social media practices enable youth to connect their online and offline activities with their interests” (p. 21), as well as take advantages of collaborative learning tools, among other conclusions. In the same line, another applied study carried out in Catalonia (Villacampa et al., 2020) concluded that adolescents’ prosumption on YouTube, that is, the creation of their own content, can be a useful tool for approaching the topic of gender violence.

Objectives and Methodology

The general aim of this study is to analyse tweens’ preferences and media practices and uses in YouTube, through the following sub-objectives:

To understand how tweens define and see YouTube among the rest of social media.

To analyse what tweens like best or dislike in YouTube (technical features, contents, interactive functions) and why.

To identify the uses or social functions tweens attribute to YouTube (e.g., entertainment, self-learning, socialisation functions).

To detect whether there is any kind of prosumption in tweens’ practices on YouTube.

To determine whether there is a gender bias in tweens’ YouTube preferences and practices.

To achieve the research objectives, the study applied a quantitative phase consisting of administering a questionnaire to 1,406 preadolescents (11 and 12 year-olds) in 41 secondary schools in Catalonia, and a qualitative phase consisting of three focus groups, with six tween participants each (three girls and three boys).

We contacted all the schools listed in the Education Department of the Government via email, asking them to participate in our study, and giving them instructions about how to administer the questionnaire. A total of 41 schools freely agreed to participate.

The final questionnaire, preceded by a pilot test carried out in November 2016 (Fedele et al., 2018), was administered online during the period December 2016-January 2017, with the presence of a teacher or a tutor.

The online questionnaire, which had a simple and attractive visual appearance, consisted of two parts:

five questions for socio-demographical purposes, respecting the anonymity of the respondent (e.g., age, sex, school);

eight questions focused on the research topics: one open question and the rest with closed responses (some multiple choice and others using a five-point Likert scale).

In the second part, four out of eight questions focused on YouTube practices, uses and preferences. In particular, respondents were asked:

Q2: What is YouTube?

Q5/Q6: What do you like/dislike about YouTube?

Q4: What do you use it for?

In Q2, respondents could select up to three of the following options: a social media, a video catalogue, a content platform, a “new” television. These are the options that coincide most closely with the observations made by McCosker (2014, p. 203), who asserted that “in its early iterations at least, YouTube’s important generative function has emerged from its multiple roles ‘as a high-volume website, a broadcastplatform, a media archive and a social network’ (Burgess and Green, 2009, p. 5)”.

In Q5 and Q6 the participants were asked, respectively, what they liked best about YouTube and what they did not like about it. The respondents were given a series of items related to YouTube, which were grouped into three categories:

technical characteristics (speed/slowness, usability, video quality);

content (music, television programs, tutorials, memes/jokes);

interactive functions (uploading videos, sharing videos, writing comments, liking or disliking material).

The content categories were based on a literature review, which identified the main types of YouTube channels (Bärtl, 2018; Williams et al., 2014 1).

Participants could also indicate other features in an open option category, whose results were coded a posteriori.

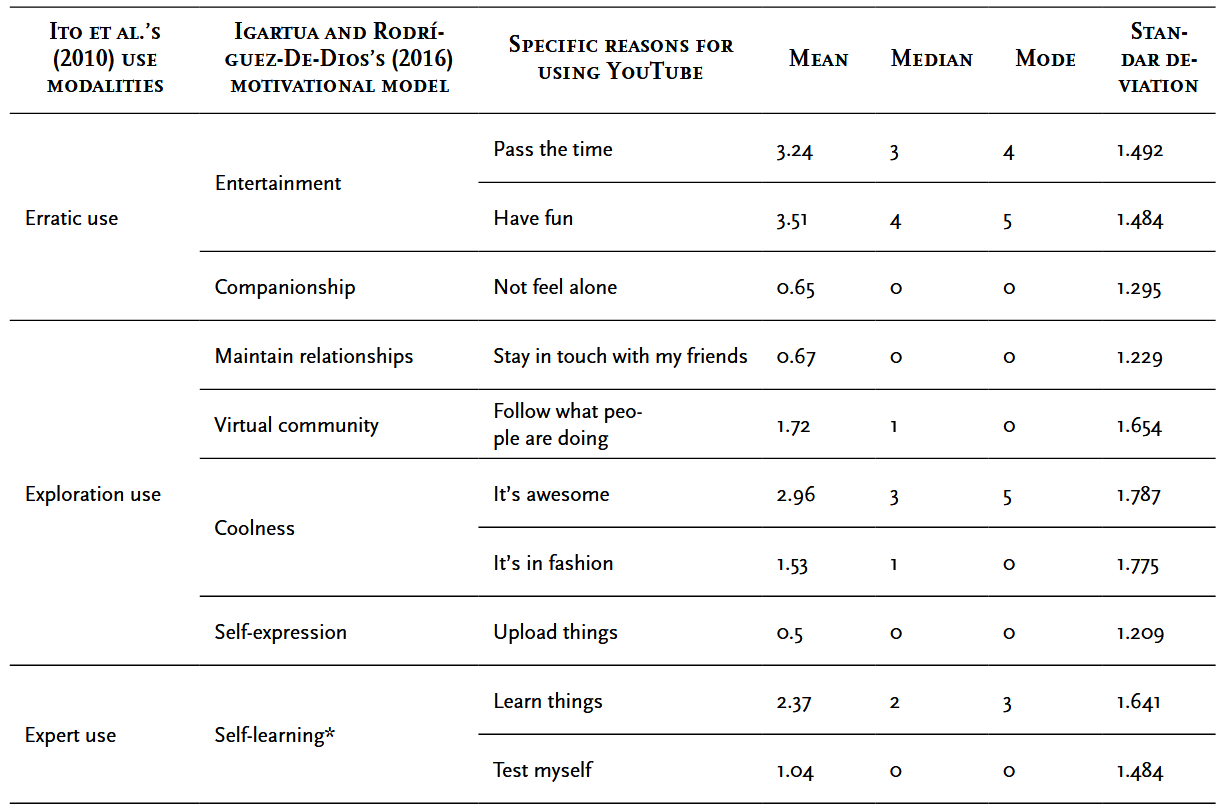

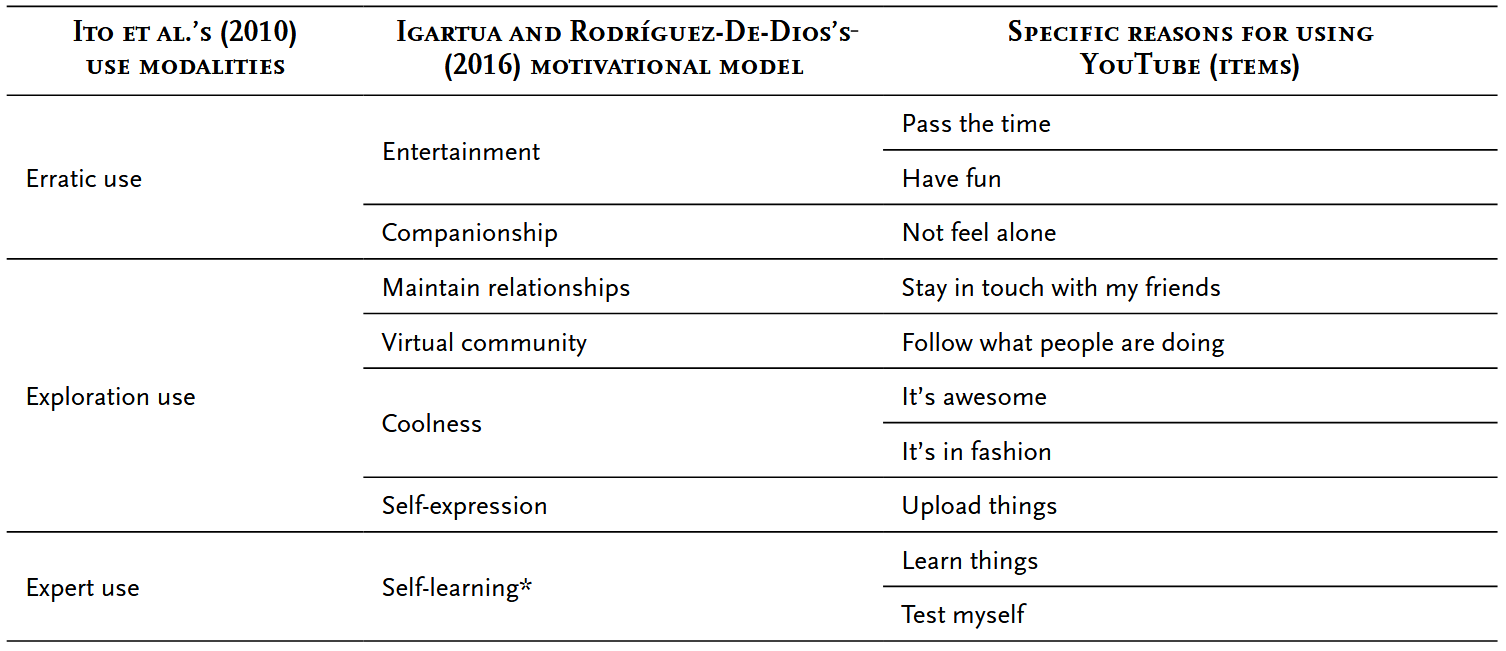

Q4 was designed as a set of five-point Likert scale questions and asked respondents to rate 10 specific reasons for using YouTube, on a scale from 1 (very little) to 5 (a lot). They also had the option of responding 0 (none). A value of three is considered the midpoint or neutral response (neither too much nor too little). According to the uses and gratification theory, “people are sufficiently self-aware to be able to report their interests and motives in particular cases, or at least to recognize them when confronted with them in an intelligible and familiar verbal formulation” (Katz et al., 1973, p. 511). Therefore, based on our theoretical framework, we combined different categories of uses and motivations from previous studies related to social media (Igartua & Rodríguez-De-Dios, 2016; Ito et al., 2010) to define specific reasons for using YouTube (Table 1, 3rd Column). We asked the participants to rate these categories from one to five.

Table 1 Models of Practices and Uses of YouTube

Note. Own adaptation of Ito et al. (2010), and Igartua and Rodríguez-de-Díos (2016)

To identify these categories of uses/practices, we combined (Table 1):

the motivational model of Igartua and Rodríguez-De-Dios (2016) on the uses of Facebook, considering that both the categories “maintain relationships” and “virtual community” can be related to a socialisation function;

the participation genres identified by Ito et al. (2010);

the self-learning function (marked with an asterisk in Table 1), a category created ad hoc following the contributions of other researchers who recognize that the new technologies provide new opportunities for self-learning (e.g., Livingstone & Sefton-Green, 2016).

Descriptive and bi-variant analyses were carried out with SPSS software, using frequency tables and descriptive statistics (mean, mode, median, and standard deviation) for the descriptive analysis, and chi-square, Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests (depending on the type of variable) for the bi-variant analysis (level of significance set at p < 0.05).

The focus groups were held in January, February and March 2017 in three of the 41 participating educational institutions. They were led by pairs of moderators who followed an interview guide based on semi-structured questions. The focus groups were recorded and subsequently transcribed.

The transcriptions were analysed following the thematic analysis procedure proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006), with the support of the Atlas.ti qualitative analysis software and the collaboration of an external researcher who is a certified Atlas.ti trainer.

The coding process was carried out by four researchers working as a group. They agreed on 21 categories, which include, for the purposes of this article, the following:

notion of social media and definition of YouTube;

preferences with regard to content selected on YouTube (music, entertainment, learning/education, etc.);

reasons for liking/disliking YouTube and functions attributed to it (based on categories of uses/practices in Table 1). In particular, the category “virtual community” includes comments such as “to follow what people are doing” and “to like”, but there are no contributions referring to making comments or keeping in contact with offline friends.

In the results section the focus group interventions are identified in the following way: focus group number (FG1, FG2 or FG3) + participant (boy/girl) + participant number (by order of intervention).

Results

Description of the Sample

A total of 1,406 students in the first year of secondary school at 41 secondary schools throughout Catalonia participated in the survey: 716 girls (50.9%) and 690 boys (49.1%). A total of 87.1% (n = 1,224) of the participants were 12 years old, with an average age of x = 12.11 (median = 12, mode = 12). In the focus groups there were 18 students from three of the schools that had participated in the previous phase: nine girls and nine boys.

What is YouTube?

When defining YouTube, two thirds of the students (66%, n = 928) only chose one of the options from the four available, 26.8% (n = 377) chose two options and 7.2% (n = 101) chose three options (x = 1.41).

No option was chosen by a majority of participants, who generally consider YouTube to be, in decreasing order, a social media (43.5%, N = 611), a content platform (41.7%, N = 587) and a video catalogue (40.8%, N = 574), and much less as a “new” television (15.1%, N = 213), although they do use it, as is noted below, in a way which is fairly similar to “traditional” television according to the televisual use identified by Pires et al. (2019). However, the focus groups revealed the variety of criteria used by pre-adolescents to identify what constitutes social media and what kinds of social media they use. They mainly mention Instagram, and, in second place, other media or applications like YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Musical.ly and WhatsApp, even though participants said that they rarely used certain networks, such as Facebook, Twitter or even Snapchat, or did not use them at all.

It should be pointed out that the focus group participants did not discriminate between social media and messaging services, such as WhatsApp, as for the majority, social media are “the applications we use to communicate with each other” (FG3Girl2), as can also be seen in this fragment from FG1:

Moderator: What are social networks for you? FG1Boy1: Yes, Instagram. FG1Girl1: Instagram. FG1Boy3: Mainly Instagram. ( … ) Moderator: You said that YouTube wasn’t a social network. Why? FG1Boy1: Yes, it is a social network. FG1Girl1: Yes, it is, but I don’t use it as a social network. FG1Boy3: Well, it’s supposed to be, but nobody uses it. It’s more to see things that interest you. FG1Girl1: Yes, a video, a song, whatever. For example, now I want to see ( ... ) an episode (of a series/program). Or you put on this YouTuber ( ... ). Or this film… people post things, I dunno, and explain what they think and so on and then you look at them. After you watch the video you can say what you think…

In the questionnaire, there were significant differences between responses made by girls and those made by boys:

More girls than boys consider YouTube to be a social media (p < 0.001), exactly 48.2% (n = 345) of girls, compared to 38.6% (n = 366) of boys.

More boys than girls consider YouTube to be a content platform (p = 0.027), exactly 44.8% (n = 309) of boys compared to 38.8% (n = 278) of girls, or a new television (p = 0.005), 18% (n = 124) of boys compared to 12.4% (n = 89) of girls.

These differences can be related to their preferences, which, as we will see below, show that boys tend to rate the technical characteristics more highly than girls, and girls tend to evaluate music content and self-learning more highly than boys.

Tweens’ YouTube Preferences

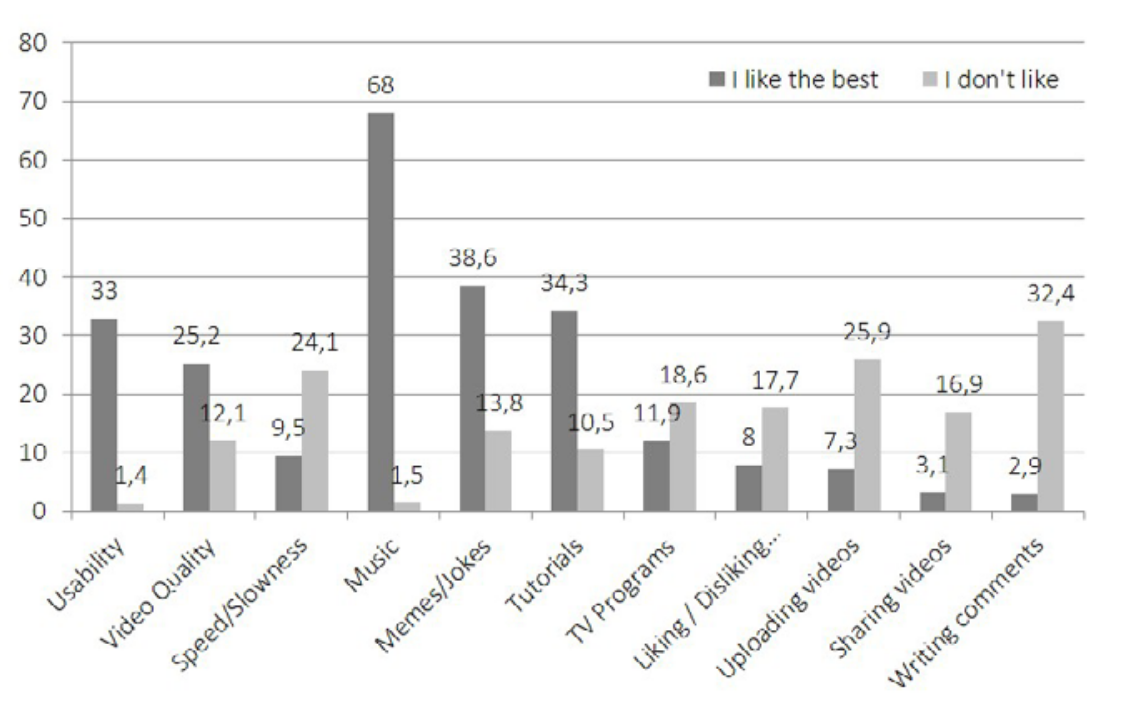

In the three groups of features that the participants like best, video content was rated highest, while the interactive functions were rated lowest (Figure 1). In particular, genuine YouTube content, such as memes/jokes and tutorials, was more highly valued than content proceeding from traditional media, like television programs.

The most highly-rated content is related to the most recurrent uses of YouTube, which are presented in the next section: entertainment (music and humour) and self-learning (tutorials).

A total of 67% (n = 940) of the sample chose three options (x = 2.51, mode and median = 3), which indicates that there was considerable variety in participants’ preferences.

A total of 9.5% (n = 133) of participants also specified other options, which were coded subsequently in the following categories:

watching videos (1.4%, n = 19), namely the “essence” of YouTube, a category which can be related to the entertainment function and to the conception of YouTube as a video catalogue and a content platform;

humorous content (1.4%, n = 19), also related to entertainment;

specific video content (4.4%, n = 61) not included in other categories, such as blogs and videoblogs, film trailers, videos of challenges, and horror, and, above all, content linked to videogames, gamers, and gameplays (2.3%, n = 32), a range of subject matter which evidences the participants’ varied interests;

following YouTubers or other famous people (1.9%, n = 27), an item which could be related to the functions of coolness and virtual community;

learning and information (0.4%, n = 6), clearly related to (self-)learning functions;

creation of own channel (0.1%, n = 1), the only category linked to self-expression and very much in the minority.

Although the bi-variant analysis detected significant differences in the gender variable in almost all the items researched, it is in the group of variables relating to content where the differences are most noteworthy. In terms of content, girls chose music (p < 0.001), tutorials (p < 0.001) and television programs (p < 0.001) more, while boys chose videos of memes/jokes (p < 0.001). This result was supported by the difference detected in the open response option (p < 0.001), as more boys indicated entertainment or videogame content.

In addition, with regard to the technical characteristics of YouTube, only usability obtains a homogeneous distribution with regard to gender, whilst more boys than girls appreciate the quality (p < 0.001) and the speed (p = 0.008) of the videos. Lastly, with regard to YouTube’s interactive characteristics there are significant differences in “uploading videos” (p < 0.001), linked to self-expression, which was selected by more boys than girls.

In the focus groups there was no spontaneous reference to any technical characteristic or function of YouTube, only content. The comments on content coincided with the quantitative results, because the majority were about preferences for music and tutorials and, to a lesser extent, about video games and memes/jokes.

What is different however about the participants’ preferences is their evaluation of what they do not like about YouTube. While the results about what they do not like mirror the responses to the question about what they like most in the questionnaire (Figure 1), the majority of participants only chose one or two options (61.3%, n = 859; x = 1.86, mode = 1 and median = 2), which indicates there are more things that they like than things they do not like.

In particular, what they like least about YouTube is its interactive characteristics, above all “writing comments” and “uploading videos”, options linked to self-expression. The bi-variant analysis by gender also confirms in an almost identical way the results of the previous question. In particular, significant differences were detected in two interactive characteristics of YouTube, “writing comments” (p = 0.02) and “sharing videos” (p = 0.01), which girls dislike more than boys.

Lastly, 10.9% (n = 153) of participants indicated other options, which were grouped as follows:

functional characteristics of YouTube (3.5%, n = 49), such as recommendations, the bell, the clickbait, the difficulty of finding certain content (such as television series), the amount of internet data needed, and, above all, the advertisements (1.4%, n = 20), and the possible dangers for minors (0.4%, n = 6), particularly in the use of their images or the danger of becoming “hooked”. These responses indicate a certain understanding of the media functioning of YouTube, what we could perhaps define as a sort of YouTube media literacy;

specific content (0.4%, n = 6), such as jokes and “nonsense”, and the “lack of netiquette and unsuitable content” (5.5%, n = 77), in other words, inappropriate or offensive comments, insults, haters, in general anything which might be likely to cause conflict and is seen as a lack of manners as well as male chauvinist, racist, homophobic, irresponsible and adult content and content showing the abuse of animals. This also includes youtubers (specified or not), above all for their inappropriate and provocative behaviour and language. These categories demonstrate knowledge of politically correct behaviour on the internet (netiquette) and are therefore connected to the digital literacy of minors, beyond their sensitivity as citizens and human beings.

The focus groups also revealed participants’ YouTube media literacy and gave a vision of participants’ dislike of humorous content that could be offensive or discriminatory. Firstly, some participants mentioned situations and youtubers who they say have made comments or behaved in a way that is inappropriate or even immoral: “I don’t like Wismischu and AuronPlay very much, for the language they use” (FG3Girl2). In contrast they do express that they like youtubers who are respectful, particularly towards their followers: “[I like] a [youtuber] to be nice, yes. There’s one called Yuya, who you could say respects her followers more” (FG3P1).

Secondly, the participants express considerable knowledge of economic interests, sponsorship and, in general, the commercial aspect of YouTube in particular and social networks in general:

FG1Girl3: It’s recorded when you’ve seen something. Because it says so below, how many views, you know. Somebody knows that you’ve been connected. ( … ) FG3Boy3: [PewDiePie] has a lot of subscribers, 50.000.000 [statistic checked: 55,883,047 subscribers on 27 June 2017]. FG3Girl1: 50.000.000 and a bit… FG3Boy2: Just over 50.000.000... FG3Boy3: I suppose he’s paid. Paid money for the video. FG3Boy2: Because he’s paid the monetisation. FG3Girl2: He’s paid. Moderator: Who pays? Some: “YouTube”, “the YouTube company”. FG3Boy1: He’s sponsored, for example… FG3Girl2: Google! FG3Boy3: And Google pays YouTube...it’s like that. FG3Boy1: And if there are advertisements, they pay you even more… FG3Boy2: Obviously! Moderator: Ok, ok… Did you work on that in class? Everybody: No, no. We just know. FG3Girl1: It’s just normally the YouTubers say so.

The conversation above clearly demonstrates the knowledge of the tweens in our sample about certain media mechanisms, such as marketing strategies, a knowledge they have picked up outside formal educational institutions.

Tweens’ Uses and Practices on YouTube

The quantitative data revealed that entertainment is the most highly-rated use (Table 2), which ties in with the results presented in the previous section.

It is surprising that, despite more than 40% of the survey respondents defining YouTube as a social media, they scarcely use it at all to follow what people are doing, to be in contact with friends or to post things.

The quantitative analysis showed significant gender differences in almost all YouTube practices, except in “learning things” (p = 0.638) and “not feeling alone” (p = 0.068). Boys tend to give higher ratings than girls to the items presented. In particular, the only two uses that are rated higher than neutral (3), “passing the time” (p < 0.001) and “having fun” (p < 0.001), are rated, respectively, four and six tenths higher by boys. In addition, boys rate the coolness item “because it’s awesome” (p < 0.001) slightly higher than average, while girls rate it lower.

In the qualitative data, and in line with the quantitative data, “entertainment” receives 31% of mentions and is one of the most frequently mentioned categories, together with “virtual community”, which received 16% of mentions. Also in line with the quantitative results presented in the previous section, the entertainment category is often related to specific content, especially music:

FG2Girl2: I watch music videos [on YouTube], mainly music. ( … ) FG1Boy3: [YouTube] it’s supposed to be social, I think, but I use it more for entertainment. Various participants: Yes. ( … ) FG1Girl2: [We watch TV series on YouTube] but they are series that aren’t on television anymore normally.

(Self)-learning (36% of mentions) was also noted in the qualitative phase, but in the focus groups it refers both to informal learning - above all in tutorials - and to a lesser extent the more formal learning provided by teachers in the classroom.

Informal learning tends to come from tutorial or do it yourself (DIY) content:

FG1Boy2: Last year I made some slippers for secret Santa, and I sewed them, I got it from a YouTube tutorial. Moderator: A tutorial about “how to sew slippers”? FG1Boy3: “How to make a gift”. FG1Boy2: Exactly. I looked for that and there was a video about slippers.

On the other hand, the combination of humour and academic content found on YouTube can be a useful tool in the classroom:

FG3Boy3: The best is the maths one… “Troncho and Moncho”. FG3Girl1: In Maths, we always get shown the videos by “Troncho and Moncho”. As our teacher always tells us we haven’t understood anything he looks for one and he knows we like YouTube a lot, so he puts it on and we concentrate better and we “get” things better.

The cross-referencing of quantitative and qualitative data suggests that YouTube is one of the main social media related to the home (97%, n = 1,343 of those surveyed, use YouTube at home), and to a lesser extent at school, to increase their knowledge. Even so, the focus groups reveal that use is mainly individual and only occasionally in the company of friends and siblings, although they do talk with their peers about YouTube contents.

Conclusions

The purpose of this quantitative and qualitative study was to analyse current Catalan tweens’ YouTube preferences, practices and uses, and to identify any gender bias that might exist. We also aimed to detect some kind of prosumption in the uses preadolescents make of YouTube, following the uses and gratification theory and previous scholars’ contributions on social media uses (Igartua & Rodríguez-de-Dios, 2006; Ito et al., 2010; Katz et al., 1973; Papacharissi, 2008; Pereira et al., 2018; Pires et al., 2019; Rubin, 2002; Whiting & Williams, 2013, among others).

To start with, participants in this study consider YouTube to be above all a social media, and secondly a video catalogue or content platform, demonstrating that they know the various possibilities, including interactive ones, even though they do not use them. In fact, they recognize that a social media is an application that allows them to remain in contact and communicate: they use the word “application” as a broad umbrella term, which also includes messaging services such as WhatsApp. In terms of gender, it should be noted that girls tend to consider YouTube more as a social media while boys see it more as a content platform, which reflects girls’ more social and relational attitudes and boys’ greater interest in technology, a difference which is also shown in their YouTube preferences and ratings.

Thus girls rate content on YouTube higher than boys, while boys rate the technical characteristics higher. Despite this, entertainment and (self-)learning content is what our participants like most. This is the very “essence” of YouTube, which offers an enormous number of videos and is, therefore, better adapted to more “traditional” consumption, such as television consumption, which contributes to shaping the audiences’ “media life”. On the other hand, although the participants are aware that YouTube is a social media that offers the chance to interact, what participants, and particularly girls, like least, are the interactive functions, especially those linked to content production (sharing their own videos) or interaction (writing comments and engaging with other users), in other words, self-expression. That is, although tweens consider YouTube to be a social media rather than a “new television”, the definition of YouTube made by most of our research participants seems to be at odds with their favourite “instrumental use” (term suggested by Steele & Brown, 1995) of YouTube, that is, watching content, especially content linked to entertainment (music and humour videos). Or, referring to the categories in Pires et al. (2019), they prefer radiophonic and televisual uses, which are those more connected to “old” media practices.

Therefore, we can see that, in line with the model of uses developed by Ito et al. (2010), erratic use - linked to “hanging out” and entertainment - is the dominant practice, but there is also a large presence of exploratory use (coolness) and “messing around” - linked to coolness and the virtual community (Igartua & Rodríguez-De-Dios, 2016) - and even, expert use - linked to “geeking out” and self-learning (Livingstone & Sefton-Green, 2016) or educative use (Pires et al., 2019). Almost completely ignored, however, are practices linked to self-expression (Igartua & Rodríguez-De-Dios, 2016), self-representation (Livingstone, 2008; Salimkhan et al., 2010), and the extension of social networks (Subrahmanyam et al., 2015), which are more connected to the social and productive uses found by Pires et al. (2019). However, YouTube does fulfil the function of sharing with the peer group (Fedele, 2011), as young people discuss the content and characters (youtubers) in conversations with friends. We could say that tweens in our study use YouTube (online interactions with the content) to feed conversations of offline interactions with peers. Hence, YouTube is involved in developing relationships amongst tweens (Colás-Bravo et al., 2013; Fedele et al., 2015), but not through the platform itself. This is more accentuated in the case of girls and is similar to the way traditional media, in particular television, is used.

YouTube is thus an integral part of the interconnected ecology (Scolari & Fraticelli, 2017), media life (Deuze, 2011; Manovich, 2009) and transmedia life of tweens in our study, who integrate YouTube into their wider multimedia practices in a “natural” way. It does not, however, seem the most important medium for socialisation, self-representation or self-expression, at least in this age range. Preadolescents in this study seem to prefer Instagram as their favourite social media for uploading original content and engaging in interaction with others. In other words, on YouTube tweens in our study are not the prosumers predicted for the new media environment, at least not at this age stage or in this platform.

Nevertheless, tweens in our study do show several of the generation Z’s characteristics indicated by Fernández-Cruz and Fernández-Díaz (2016), since they appear to be quite expert in understanding the technology (what we have referred to as a sort of YouTube media literacy), they are multi-taskers, socially open, and fast in the use of technology tools such as YouTube.

Although YouTube has unquestionably made it easier for users to publish their own audio-visual content, it is also true, as our study points out, that while for the vast majority of tweens verbal comments between peers and sharing are important components in the sense of active and creative participation, content production and publication on this platform are not media practices that are of interest to them. The general picture shown in our findings is that tweens use YouTube to consume media content in a traditional manner, rather than in a more interactive way, although YouTube does form part of tweens’ transmedia life.

To understand how those in this age range respond to the possibilities offered by the new media ecosystem as places for prosumption, it seems suitable to focus future research on other social media that have emerged in this study, above all Instagram. It would be interesting to apply more participatory approaches, such as the ethnographic approach used to carry out workshops with children (de la Fuente-Prieto et al., 2020) and adolescents (Villacampa et al., 2020).

To conclude, we would like to highlight the relevant informal knowledge of YouTube that the tweens have shown. We believe that this opens a window of opportunity to promote more deeply the educational and cultural potential of social media within the framework of media literacy. As one example, the fact that our research participants, despite being very young, are fully aware of the marketing elements incorporated in YouTube or in youtubers’ content and strategies, shows us the level of understanding that these young generations already have about online environments.

texto em

texto em