Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicação e Sociedade

versão impressa ISSN 1645-2089versão On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.39 Braga jun. 2021 Epub 30-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).2789

Thematic Articles

Building Trust in Digital Platforms for Sharing Collaborative Lifestyles in Sustainable Contexts

1iDepartamento de Comunicação e Arte, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

A designação de “economia de partilha” pretende identificar um conjunto de relações sociais, digitalmente mediadas, baseadas nos princípios da reciprocidade e confiança. Todavia, tais princípios devem resultar dos requisitos tecnológicos e de design das plataformas utilizadas onde os utilizadores depositam os seus dados pessoais, inserem informações sobre interesses e práticas quotidianas, comunicam com desconhecidos e, desta forma, criam vínculos pessoais. Este estudo tem como objetivo identificar um conjunto de diretrizes para a construção da confiança na partilha de estilos de vida colaborativos mediada digitalmente por plataformas que promovem partilha de experiências em contextos sustentáveis. Neste estudo, a partilha de estilos de vida colaborativos é compreendida como uma troca social não monetária de conhecimentos, habilidades, acomodação e alimentação. As plataformas analisadas, Volunteers Base, The Poosh e WWOOF Portugal, são organizações não comerciais que promovem experiências em projetos de educação em ecovilas, de construção natural em zonas rurais, de permacultura em quintas, entre outros. Realizou-se, portanto, um estudo multicasos e documental dos termos e políticas divulgados por estas plataformas digitais. Estes documentos reguladores foram submetidos a uma análise de conteúdo com auxílio dos softwares Iramuteq e MAXQDA. Desta análise emergiram 20 diretrizes, em três categorias: “práticas e condutas”; “condições”; e “segurança e privacidade”, que podem orientar os utilizadores e as plataformas na intenção de construir relações de partilha mediadas digitalmente de forma transparente e confiável.

Palavras-chave: plataformas digitais; partilha; estilos de vida colaborativos; confiança; sustentável

The term “sharing economy” is intended to identify a set of social relations, digitally mediated, based on the principles of reciprocity and trust. However, such principles must result from the technological and design requirements of the platforms used where users deposit their personal data, insert information about interests and daily practices, communicate with strangers and, in this way, create personal bonds. The study hereby presented aims to identify a set of guidelines for building trust in the context of digitally mediated sharing of collaborative lifestyles, on platforms that promote the sharing of experiences in sustainable contexts. Within the scope of this study, sharing collaborative lifestyles means a non-monetary social exchange of knowledge, skills, accommodation, and food. The analyzed platforms - Volunteers Base, The Poosh, and WWOOF Portugal - are non-commercial organizations that promote experiences in educational projects in eco villages, natural construction projects in rural areas, permaculture projects on farms, among others. A multi-case and documentary study of the terms and policies published by these digital platforms was carried out. These regulatory documents were submitted to content analysis, using the Iramuteq and MAXQDA software. From this analysis, 20 guidelines emerged, in three categories: “practices and conduct”, “conditions” and “security and privacy”, which can guide users and platforms in the construction of digitally mediated sharing relationships in a transparent and reliable way.

Keywords: digital platforms; sharing; collaborative lifestyles; trust; sustainable

Introduction

Digital environments have specific strategies to provide confidence in digital services - interface design, filters, data protection, and privacy mechanisms, among others. However, in addition, they also need to assist in the emergence of mutual trust between users.

The cognitive and affective experience of trust is one of the most important requirements of social life. Some studies address this socio-anthropological component, in the digital system, as a relevant element to establish the quality of man-screen-network interaction (Adali et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2013; Cheshire, 2011; Hang et al., 2009; Igarashi et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016; Zhang & Wang, 2013). In this approach, for example, Fogg’s (2003) research on persuasive technology stands out, emphasizing trust as a central element of credibility in web service experiences.

On the other hand, in a classic sociological approach, trust also plays a significant role in the quality of interpersonal relationships built in different social spaces. Luhmann (1979/2005) treats the trust as a diminisher of complexity and considers communication as the basis of social interaction. The possibilities of interaction between individuals and the organization of the social order itself imply different ways of experiencing this complexity. As a result, there is a need to simplify and make relationships somewhat expected, given the diversity of potentially unpredictable or trivialized behaviors (Bauman, 2003/2004).

In the sharing economy transactions, trust between strangers who exchange needs and resources appears as a way to understand the relationship between peers, as explained by Rachel Botsman in the communications published by the YouTube Channels Stern Strategy Group (2015) and TED (2016). The sharing economy encompasses a social system based on personal relationships and ancient principles, including trust. However, the trust that directly affects the intention to share is also challenging in the face of the obstacle of being built among strangers.

The sharing of collaborative lifestyles understood in this study is digitally mediated and involves a non-monetary social exchange of knowledge, skills, accommodation, and food. Digital platforms are, therefore, fundamental tools for information and communication between volunteers (users who offer to participate, without monetary remuneration, in exchange for contexts where they can acquire certain skills) and hosts (users who make their knowledge available free of charge and a social space where this learning can happen).

The study hereby presented aims to identify a set of guidelines for building trust in the context of digitally mediated sharing of collaborative lifestyles, on platforms that promote the sharing of experiences in sustainable contexts.

The analyzed platforms - Volunteers Base (https://www.volunteersbase.com/), World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms, Portugal (WWOOF Portugal; https://wwoof.pt/) and The Poosh15 - are non-commercial organizations based on a network for sharing collaborative lifestyles. In this type of sharing we are interested in sustainable contexts, such as educational projects in eco villages, natural construction projects in rural areas, permaculture on farms, among others.

These projects enhance sustainable development, offering productive diversity through natural resources and a more nature-integrated lifestyle. A study about the sustainable context, in rural and intermediate areas, is also justified by the territorial importance of these regions in the European Union. In addition, the low economic and social development of these areas shows that there is still a lot to explore and to value (Europe Union, 2018).

In fact, rural regions cover 44% of the European Union’s territory, while intermediate regions account for 44% and urban regions represent only 12% of the territory (European Union, 2018). This territorial importance is even more significant in Ireland, Finland, Estonia, Portugal and Austria, where the predominantly rural regions represent around 80% (Europe Union, 2018).

According to the presented scenario, a multi-case and documentary study of the terms and conditions published by Volunteers Base, The Poosh, and WWOOF Portugal was carried out. These regulatory documents were subjected to content analysis, using the Iramuteq and MAXQDA software. From these analyzes, 20 guidelines emerged that can guide users and platforms in building digitally mediated sharing relationships in a transparent and reliable way.

Collaborative Lifestyle in Sharing Economy

The sharing of lifestyles comprises a convivial and “onlife” (Floridi, 2015) experience, potentiating collective consequences. The construction of relationships takes place through digital platforms on which users deposit personal data, insert daily information, communicate with strangers, and, above all, collect bonds.

In this perspective, according to Botsman and Rogers (2010/2011, p. 146) and Shirky (2010/2011), a product or place belonging to a subject (a car, a house, a farm, etc.) becomes part of a “shared context” when added to a digital platform, and function as an “anchor of commonality”.

A sense of community, as McMillan and Chavis (1986) argue, is capable of nurture a feeling of belonging and influence among users, the sharing of stories and experiences, and the satisfaction of meeting needs through participation in the collectivity.

At first sight, a sense of community can be perceived on many digital platforms of the sharing economy, in different contexts or approaches - on the Olio (http://olioex.com/) and ShareWaste (http://sharewaste.com/) platforms, from food sharing or from the donation of recyclable objects accumulated in domestic waste, forming a network to fight waste or functioning as a chain of the circular economy.

However, the sense of community can be more complex. Some platforms also involve coexistence and exchange in a living space (Chan & Zhang, 2018), which can be, for example, the home of a farmer willing to accommodate a volunteer who wants to learn and work on organic farming projects. Private spaces, previously closed, open as environments for the exchange of knowledge, skills, and also values.

Botsman and Rogers (2010/2011) explain that, in a social space, the intimacy between peers creates a feeling of greater unity and trust, like what happens in virtual communities where there is an ideal of organization. This ideal leads users to a feeling of mutuality, giving them a reason for collective creation (Botsman & Rogers, 2010/2011, p. 146).

The collaborative lifestyle can, therefore, be an enhancer of collective movements and capable of contributing to development in several sectors. Digital platforms within this logic also take on more complex challenges, based on the goal of supporting reciprocal and reliable bonds. In this context, ensuring the security and transparency of the experiences they promote through policies and regulations is of great importance.

Trust That Platform Resources and Policies Inspire

The establishment of trust is initially associated with the users’ observations and perceptions about the characteristics of the platforms, reflecting the users’ needs and the quality of the system, information, and services. Within the scope of the sharing economy, a set of aspects assume great relevance, namely, those related to the technologies used, the quality of information, the communication resources, the security and privacy tools, and the documents that regulate the use and participation in the experiences.

Kamal and Chen (2016) investigated the trust factors that affect people’s willingness to participate in the sharing economy and pointed out two main conclusions. The design of these platforms is the first of these factors, in addition to using current and reliable technologies. These conclusions are corroborated by Lee et al. (2018), who refer to: (a) system quality, due to the need to explore the advantages of good usability, the convenience of access, ease of use and other aspects; and (b) information quality (or informativeness), due to the need for a set of information that brings value to the user’s perception.

In this way, and also according to Kamal and Chen (2016), the platforms should provide the user with the most consistent and necessary information. Not knowing the host name or the location of the accommodation, for example, can be crucial for the volunteer to classify the platform as unreliable.

On the other hand, the familiarity between the user and the system can have an impact on building trust. For Santos and Prates (2018), this familiarity is a consequence of the signification system adopted by the designer in the interface. In other words, the visual environment of the platforms that promote collaborative lifestyle experiences is undoubtedly relevant in building trust.

Another topic of great relevance and also studied is the security and privacy of users. Lutz et al. (2018) developed a model based on privacy concerns, highlighting that sharing transactions usually raise privacy and security concerns, which extend from virtual environments to physical ones.

Before enjoying the benefits of collaboration, such as living with new people and the established compensations, users expose their personal data and exchange information with strangers on digital platforms (Chuang et al., 2018; Lutz et al., 2018), which implies the need for security and protection mechanisms on the platforms.

Corroborating this, Yang et al. (2016) identified three general indicators: (a) security and privacy; (b) information technology quality, and; (c) platform traits. Other authors (e.g., Kamal & Chen, 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Santos & Prates, 2018) extend this contribution, including new indicators that can determine the construction of trust.

In the personal dimension, Santos and Prates (2018) included indicators that respond to a concern for the safety of users, namely: (a) data, referring to the personal information provided in the sharing economy systems; (b) authentication, referring to the verification carried out by the system in relation to the users themselves or their data; and (c) privacy, referring to the level of privacy defined by the user when using the sharing economy system.

Concerns about security and privacy should, therefore, be of paramount importance for digital platforms in the context under study. It can also be argued that, as far as trust is concerned, the adoption of security and privacy resources and tools by the platforms is strategic and can potentially help them to be perceived as more reliable and ethical.

However, some authors consider that the platforms themselves access the data in an abusive way and use, store or transfer it in ways that question the rights of protection and security of users. Lee et al. (2018) mention the possibility of malicious use of user data by the platforms, such as the sale or disclosure of personal data, in addition to the potential (physical) damage that the experience promoted by the platform can cause to the user.

As protection measures, a platform can offer tools and services that ensure users’ experiences (Kamal & Chen, 2016; Santos & Prates, 2018): criminal background check, basic user information, security certificate, video chat, and insurance assistance.

As far as verification is concerned, some platforms carry out a screening and investigation service for users, monitoring violations of regulations, terrorism, and sanctions, in addition to criminal background checks. These initiatives can be seen as another security method, although they do not prevent adverse situations.

It is a fact that any experience has its share of risk and, therefore, it becomes a challenge to avoid all threatening events (either from the user or the platform). But being thoughtful and taking action towards online and offline security are concerns that must remain at the heart of discussions about the sharing economy.

Although the sharing economy platforms should prioritize information organization, along with security and privacy tools, they also need to consider the political and social issues behind their services, as community culture and rules can also raise quite complex issues. Regulations, terms, manuals, campaigns, and other documents can be considered in order to institutionalize an ethical culture among members of the community.

Ye et al. (2017) have a more humanized view: the ideological and ethical nature of the attitudes of members of the sharing communities has a strong relationship with the platform’s reputation. These authors developed a research model to describe the stages of trust development between users. In this model, reputation comes from the degree of emotion perceived by users when reading personal information, assessments, or recommendations on a platform. In other studies, reputation is also cited as relevant in building trust (Kamal & Chen, 2016; Tian et al., 2017; Ye et al., 2017; Yoon & Lee, 2017).

Also, Wu et al. (2017) concluded that users infer reliability from photos (present in users’ profiles, albums, or comments). In the photos, the user identifies elements with which he identifies, developing a feeling of empathy. This study highlights that photos are, therefore, important information elements for the construction of trust.

These observations reveal that the information shared by users exposes their behaviors and influences the perception and decisions of others, as well as reinforces a platform’s community identity.

In turn, the conduct of users when using the platforms is outlined by the rules and standards that these platforms develop and promote. It is therefore relevant to analyze these recommendations.

Method

This multi-case and qualitative study aimed at a documentary and descriptive analysis (Gray, 2014; Stake, 2006) of the deontological apparatus, such as the terms and conditions, used by online platforms that promote collaborative lifestyles experienced in sustainable contexts - educational projects in eco villages, rural construction, permaculture on farms, among others.

As such, three platforms - Volunteers Base, The Poosh, and WWOOF Portugal - were selected, using the following criteria: being a non-commercial organization, involving non-monetary social exchange, and promoting experiences in Portugal. Volunteers Base promotes this type of sharing in several contexts, including sustainable ones. The Poosh focuses exclusively on sustainable construction, while WWOOF Portugal promotes experiences on organic farms.

Data collected on these platforms were treated and analyzed in two phases: the first with the aid of the Iramuteq software and the second with the MAXQDA software. In the first moment of analysis, textual statistics were used, to infer the occurrence and association between words, in order to understand the discourses promoted by the platforms through the regulatory documents (terms and conditions).

A total of six regulatory documents, from The Poosh (terms of service), Volunteers Base (terms of use and policies for volunteers and hosts) and WWOOF Portugal (terms and conditions of use and privacy policy), separated into 231 text segments (ST), were analyzed with the aid of the Iramuteq software. A set of 8,236 words emerged from these documents, with 1,499 distinct terms (without derivations or similarities with any other identified terms) and 758 with a single record, that is, they appeared only once in these documents.

This content was subject to two types of textual statistics: correspondence factorial analysis and analysis of similarities. In both cases, the software uses the Reinert method for a statistical formulation of repetition and the relationship between the words used in the different speeches (http://www.iramuteq.org/). The factorial correspondence analysis allowed us to classify the quantity and repetitions of words, identifying and comparing the speeches of the platforms; in turn, the similarity analysis allowed us to represent the association between the words used in the documents and to infer the construction structure and the themes that arose from the platforms’ speeches.

The same documents were then subjected to content analysis, in order to deepen the treatment and generate a descriptive codification (Bardin, 1977/2011). Data were processed using the MAXQDA software. This analysis phase resulted in what we call guidelines, which emerged from the analyzed corpus, also considering the theoretical framework studied and the references raised in previous publications (Sales et al., 2020).

This second phase of analysis resulted in 20 guidelines, separated into three sets: “practices and conducts”, “conditions”, and “security and privacy”. The treatment and analysis of the data through two distinct, but complementary techniques, and the visual tools of the two used software allowed the cross-validation of the results for the discussions, resulting in a more reliable and productive study.

Words Counted in Terms and Conditions: An Analysis

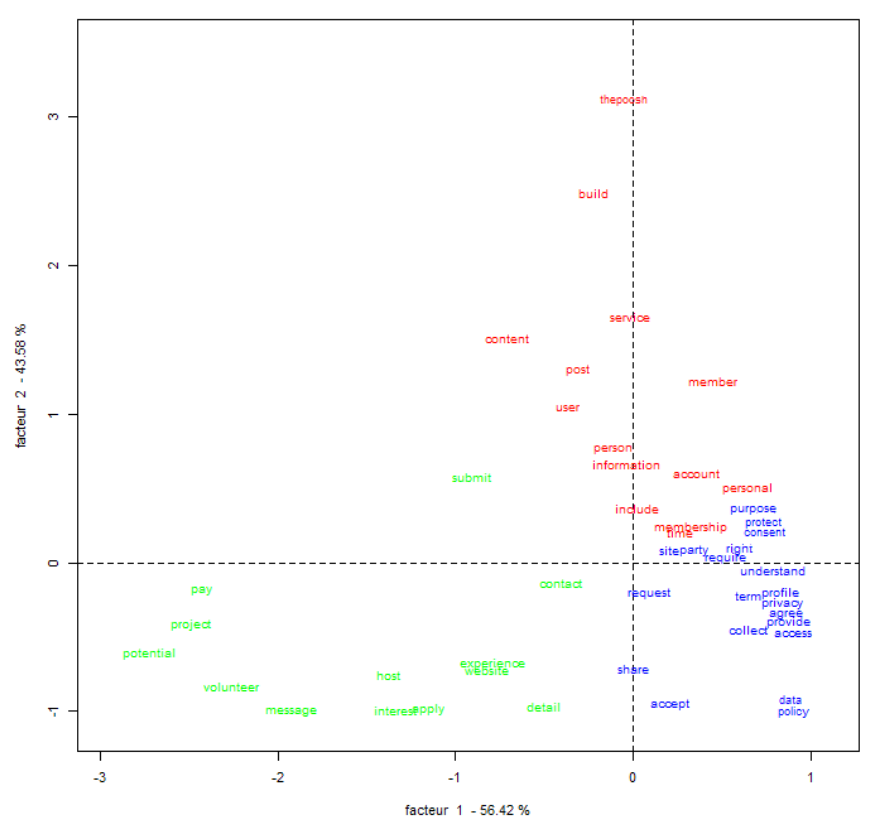

Through the factorial correspondence analysis (AFC) it was possible to verify the occurrence and make comparisons between the different words used by the platforms in the regulatory documents. The different representations that platforms have of the objectives and the promotion of sharing experiences stand out.

Volunteers Base most frequently used the words16: “volunteer”, “project”, “host”, “contact”, and “potential” (shown in green in Figure 1); The Poosh highlighted: “service”, “org”, “thepoosh”, “information”, and “user” (shown in red in Figure 1); and WWOOF: “data”, “site”, “wwoof”, “provide”, and “policy” (shown in blue in Figure 1). From this, differences in the platforms’ speeches can be observed, although there are also intersections. In addition, no record of the word “trust” or derivatives has been identified.

The use of these words in the platforms’ speeches was also analyzed. Volunteers Base is attentive to users and experiences, emphasizing the projects and activities that are necessary and that are decent to be offered among users. Based on this, there is a greater focus on experience and information on the projects published on this platform, as well as on the fulfillment of the commitments between volunteers and hosts.

The Poosh presents a speech more focused on the relationship between users and the organization and between users themselves. In this way, there is a concern with delimiting the platform’s services, as well as describing the possible services to be provided among users. Another aspect of The Poosh’s speech is focused on the treatment of content (as well as data) by the platform, in order to also emphasize how users should treat and disseminate this content.

In turn, WWOOF Portugal demonstrates that user data is at the heart of the platform’s concerns, using the word “data” to clarify how the user data processing works. The name of the organization, WWOOF, was used most of the time to declare the intentions and the way of acting of the platform, as well as the responsibilities and policies of the organization, with emphasis on the privacy policy.

Comparing the platforms, the speeches that come closest are those of The Poosh and WWOOF platforms, with proximity in terms of occurrence for the words: “information” and “person” (Figure 1). This can be explained by the fact that these platforms’ speeches are both focused on the responsibility of them and the users and on the treatment of data and content, according to the accounted words.

There is, however, no common word of great significance that strongly correlates the speeches of the three platforms under study. On the contrary, the cartesian representation demonstrates that the most frequent words are dispersed, indicating that there are differences in the contents of the regulatory documents.

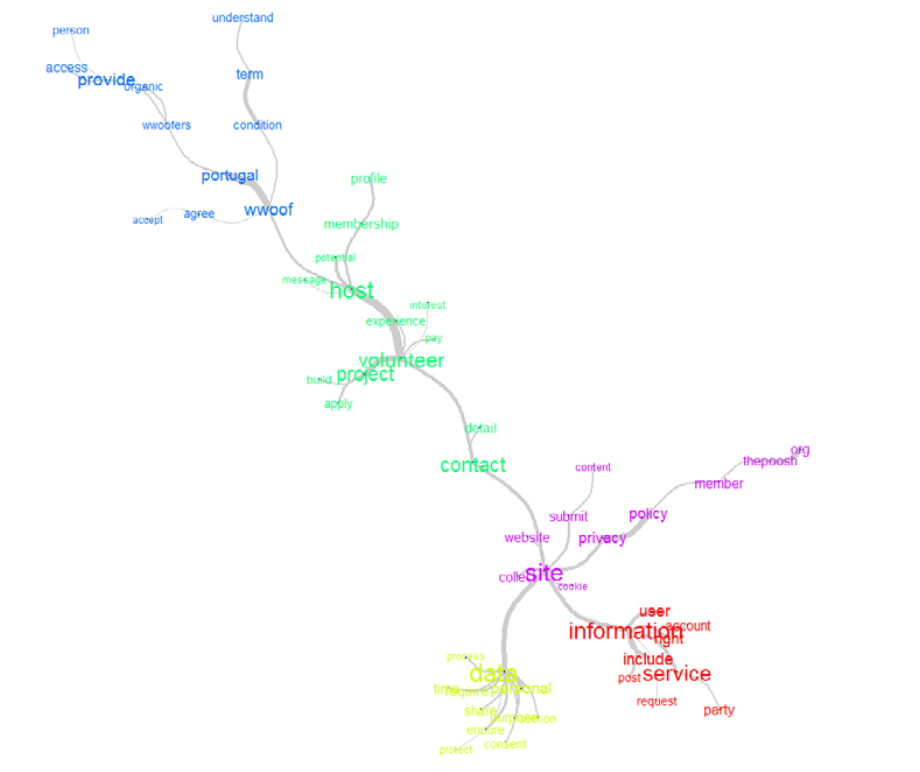

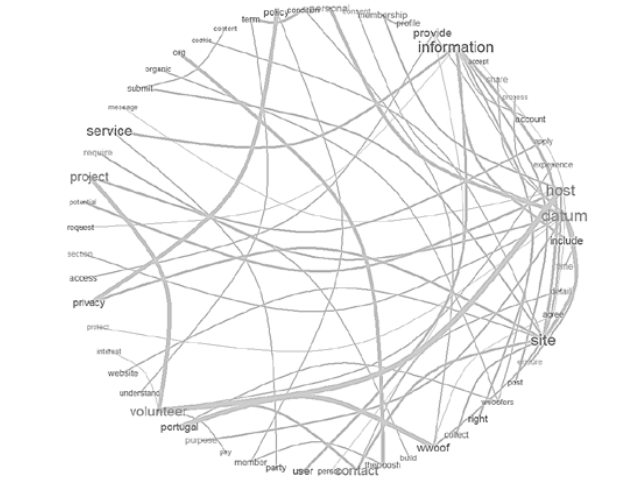

The observation of occurrences between words and their related ones led to the identification of intersections, that is, a structure of related contents in the general textual corpus of the regulatory documents under study. In fact, five words stand out in the speeches: “data”, “site”, “information”, “host”, and “volunteer”. They branch out from others that have significant expression, such as: “personal”, “right”, “service”, “user”, “privacy”, “policy”, “contact”, and “project” (Figure 2).

From what is observed, it is possible to conclude that, in general, the speeches of the platforms present typical references of any document whose content is related to the security and privacy of users, with the culture and rules of these communities, and with the quality of technology and information on these platforms, corroborating the studied theoretical framework (Chuang et al., 2018; Kamal & Chen, 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Lutz et al., 2018; Santos & Prates, 2018).

The analysis of similarity also allows the interpretation of the platform’s speeches through the association of and the relationship between the most frequent words (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Classification Result by the Reinert Method - Analysis of Similarity and Coherence in Speech

It can be inferred that the word “information” appears, in the platforms’ speeches, associated with “user”, or, more specifically, with the way the information should be used by the platforms and their users. Another association, between the words “privacy” and “site”, also explains other things about the use of their sites, reinforcing that platforms are concerned with clarifying the use of their sites. “Information”, in turn, also has a strong connection with the word “service”, a fact that also confirms the platforms’ intention to determine the services being promoted.

The word “data” appears associated with the word “personal”, referring to the treatment of user information. The users, in turn, play the roles of volunteer and host, and these two words appear strongly associated, demonstrating a significant relationship that must exist between these users. Finally, the association of the words “volunteer” and “project” points to a need to describe and detail the projects, in order to clarify users about the experiences (or experience proposals) that are promoted on the platforms.

Textual statistics and a more focused look at the platforms’ speeches also reveal potential aspects for a broader understanding of the trust-building process. Among them are: (a) the relationship that the platforms understand to exist between the processing of personal data and the recognition of users’ rights; (b) the concern to clarify the functionalities of their sites to users, as well as informing them about the services they may (or may not) find on these sites; (c) the recognition of the need for users to protect their personal data, such as telephone contacts, emails, addresses; and (d) the fact that they give relevance to the relationship between users (volunteers and hosts).

These aspects are discussed below, identifying the text passages taken from the regulatory documents that confirm these observations.

The Emergence of Trust-Building Guidelines

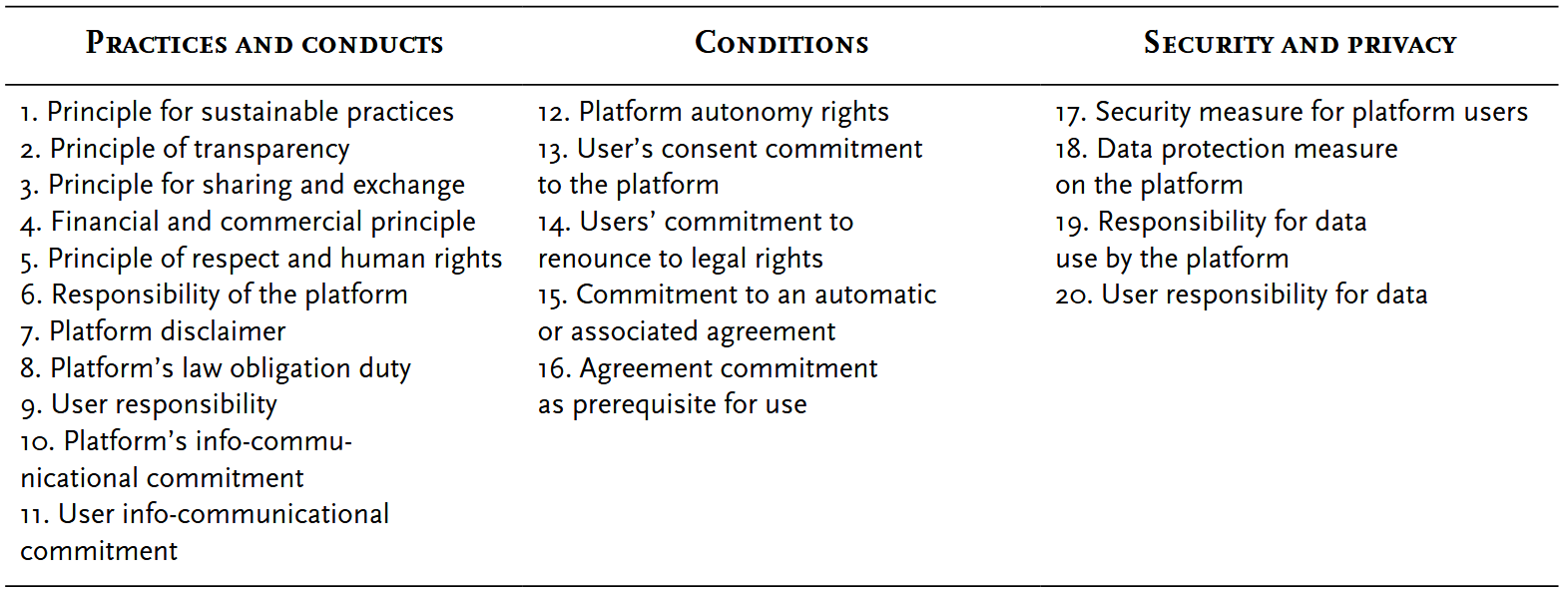

The guidelines identified in this analysis phase were organized into three categories: “practices and conducts”, “conditions” and “security and privacy” (Table 1).

Table 1 Categories and Guidelines

The first category includes 11 guidelines concerning the principles, responsibilities, commitments, and duties of the individuals in the experiences of sharing collaborative lifestyles in sustainable contexts, more specifically, users and platforms.

Under the “conditions” category are guidelines that reflect users’ rights listed by the platforms and three commitments that permeate the participation of users. The third category added four guidelines: two responsibilities, and two measures on the use, protection, and security of data and users’ privacy.

In a general comparison between the platforms’ regulatory documents, the most significant category is “practices and conducts”, with the largest number of guidelines and text segments. In this category, a no-less-important guideline, but which is not highlighted in the individual analysis, is the “responsibility of the platform”, with more text segments in the documents of WWOOF Portugal.

This platform seems to be concerned with assuming its responsibilities and intentions when it states, for example:

we will not, however, send you any unsolicited marketing or spam and will take all reasonable steps to ensure that. We fully protect your rights and comply with Our obligations ( … ). In any event, We will conduct an annual review to ascertain whether we need to keep your data. Your data will be deleted if we no longer need it. Any reports of harassment between a host and WWOOFer will be investigated by WWOOF Portugal, and may be cause for membership being revoked.17

The “conditions” category has the lowest number of segments per guideline, making it the participation deontological category of less significance. The most relevant guideline in this context is the “user’s consent commitment to the platform”, a fact that allows us to state that all the three platforms ask, in some way, the users’ permission to use personal data and published content.

Also, in the “conditions” category, there are three other guidelines with few segments, namely, “platform autonomy rights”, in which the platform is authorized to modify the published regulatory documents at any time, “users’ commitment to renounce to legal rights”, in which the platform imposes on the users a commitment to renounce to their legal rights, as in the case of legal proceedings against the platform or third parties connected to it, and “commitment to an automatic or associated agreement”, implying that, by agreeing to one term, the users are agreeing with the others terms and conditions associeted. These last two are quite questionable, since they are an imposition of platforms and can be legally questioned.

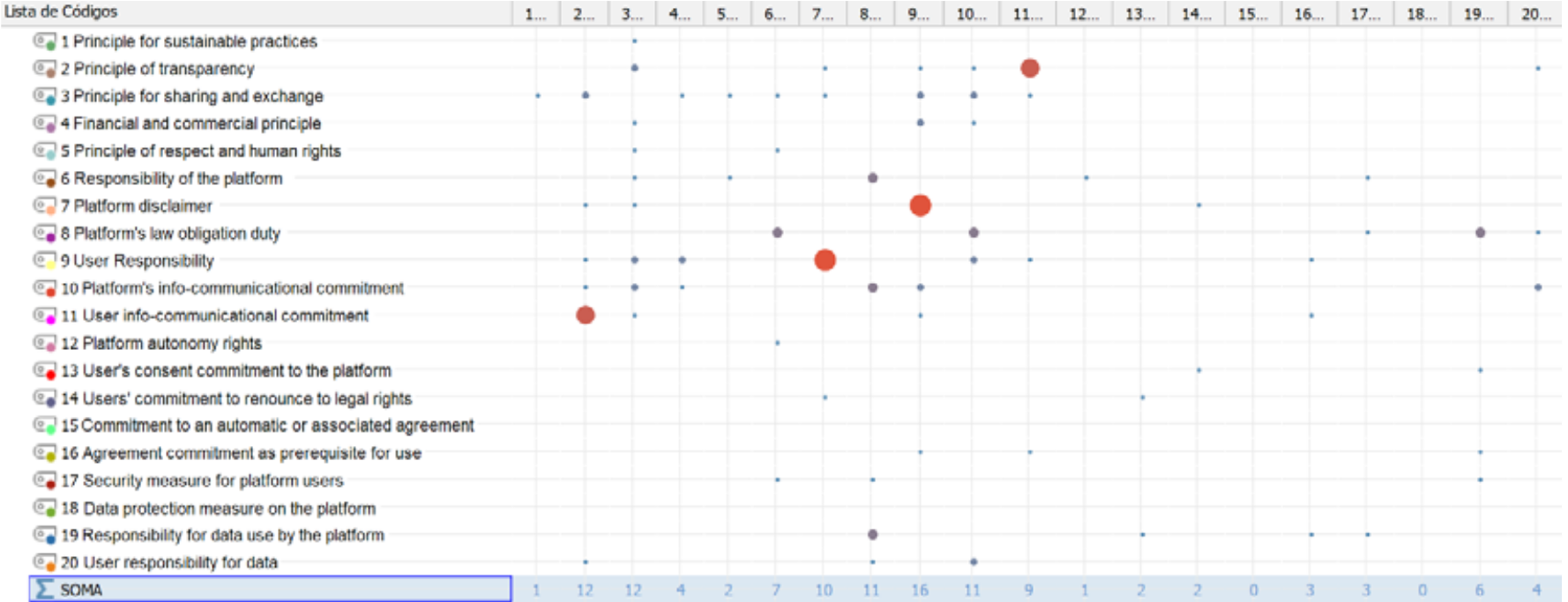

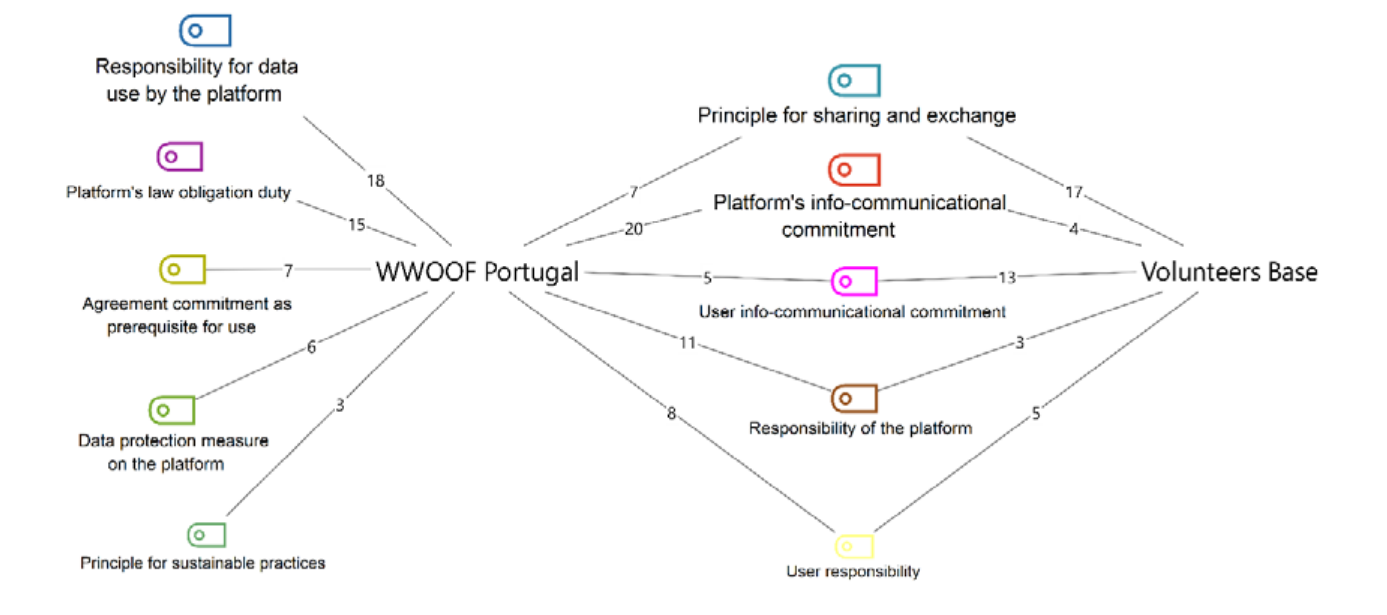

Through the connection analysis between codifications, two relevant relationships were found in the category “practices and conducts”, one more positive than the other. The guideline “user info-communicational commitment” has a connection with the “principle of transparency” and the “user responsibility” guideline has a connection with the “platform disclaimer” guideline (Figure 4).

The first connection becomes clear, for example, in segments such as: “we encourage Hosts and Volunteers to communicate extensively and to clear up all doubts before making any agreement” or “is not a bad idea to share any of your proles in sites like BeWelcome or CouchSurfing where potential hosts can see references and comments that people wrote about you”18.

The incentive for the user to inform and communicate with others appears along with the relevance of being clear and reliable. The platform, therefore, demonstrates a concern to guide users towards transparent conduct, providing information, and communicating.

In the second connection, however, the concern with users seems to lose importance, because in the platforms’ documents the users’ responsibilities have a connection with the platforms’ disclaimers.

The following segment, for example, establishes limits for the organization’s responsibility, transferring responsibility to the user and explaining the platform’s activities as follows: “is limited to providing a means of contact between Hosts and WWOOFers, and that the arrangements I make with volunteers are entirely my own responsibility”19.

When platforms state that “the content of this website is entirely submitted by users”20, it seems to be important to emphasize that the content is the users’ sole responsibility, once again exempting the platform from any control or compromise.

An Individualized Analysis of the Guidelines, by Platform

In a more individualized analysis of the codifications, by platform, through the single segment model processed in MAXQDA, it is possible to better understand the guidelines identified in each document, which clarify the philosophy of each of the platforms analyzed.

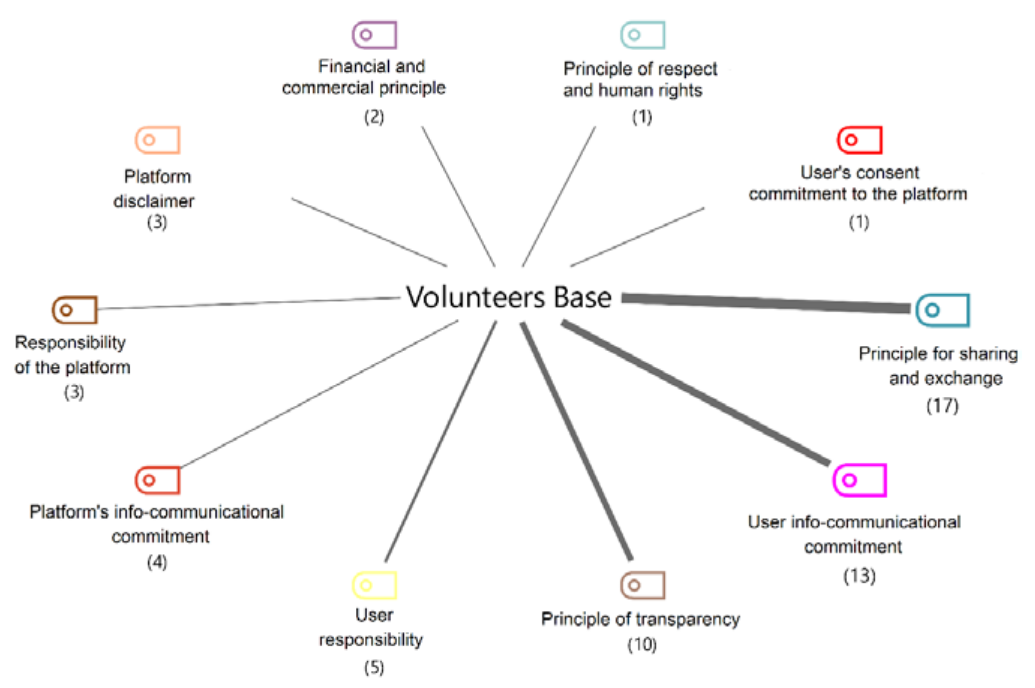

Volunteers Base emanates the greatest number of guidelines through the following: “principle for sharing and exchange”, “users’ info-communicational commitment”, “principle of transparency” and “user responsibility”. Volunteers Base provides recommendations on commitments that must be made by users with respect to information and communication, informational transparency between users, and users’ commitments regarding their responsibilities to themselves and others. The guidelines and the respective number of segments can be seen in Figure 5.

In these guidelines Volunteers Base mentions, respectively: “both parties will be participating in a moneyless volunteering network”; “to get positive answers, you should write a nice and friendly message, including information about yourself and telling your potential Host why do you want to join his/her project”; “note: many projects are run in very low budget, if you can’t provide food for example, please make it clear in you description”; “the deals made between Hosts and Volunteers are totally private and this site doesn’t take any part in it”21.

The platform maintains, in general, a concern with the users’ commitments and conduct, being enlightening and often a kind of advisor.

On the other hand, Volunteers Base does not include eight of the guidelines identified in other platforms’ documents, being, in this perspective, the platform that most differs. The “platform’s law obligation duty”, for example, the most referenced guideline in WWOOF Portugal documents, was not considered by Volunteers Base, that is, Volunteers Base does not recognize and mention a law to which it is obligatorily submitted.

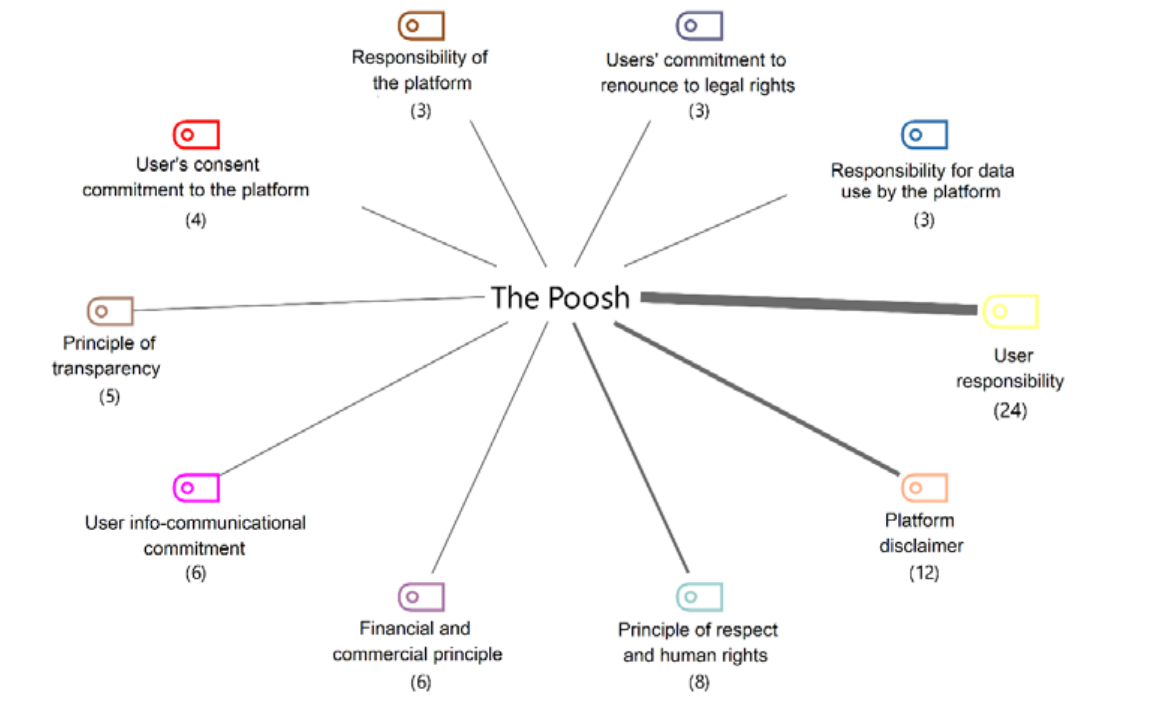

In The Poosh’s individual analysis, it is possible to recognize the priority given, in its regulatory documents, to the guidelines “user responsibility, platform’s disclaimer” and “principle of respect and human rights” (Figure 6). This observation is consistent with what was verified in textual statistics.

The platform requests a commitment from users regarding their responsibilities to themselves and others (physical and mental security, actions, guarantee initiatives - insurance, visas, and other paid services), similarly to Volunteers Base. Regarding this matter, phrases such as “in your use of our Services, you must act responsibly and exercise good judgment”22 are highlighted in the documents.

The Poosh also uses these documents to clarify the limits of its services and to exempt itself from certain responsibilities: “we do not investigate any user’s reputation, conduct, morality, criminal background, or verify the information such user may submit to the Site”23.

Identity verification is a feature available on other platforms, and, from the way The Poosh addresses this issue, it seems like a justification for being exempt from any charges in this regard. In addition, in the sentence following this statement, the platform addresses the user as follows: “we encourage you to communicate directly with potential hosts and guests through the tools available on the Site and to take the same precautions you would normally take when meeting a stranger in person for the first time”24.

Another guideline identified in The Poosh (and Volunteers Base) documents, but with less representation, is the “financial and commercial principle”. Also having limits’ establishment in mind, the platform uses this principle for stating the prohibition of using the platform’s services for commercial purposes, demand any payment from volunteers, and provide a platform link to a commercial website.

Something that should be positively emphasized in The Poosh documents is the appreciation of the “principle of respect and human rights”, which defines a set of guidelines for anti-harassment, anti-discrimination, and against any behavior that violates the law.

The platform establishes, for example, that the user cannot send any content that: (a) is defamatory; (b) contains nudity or sexually explicit content; (c) can denigrate any ethnic, racial, sexual or religious group by stereotyped representation or otherwise; (d) explore images of individuals under the age of 18; (e) represents the use of illicit drugs; (f) make use of offensive language or images; and (g) characterize violence as acceptable, fascinating or desirable.

On the other hand, The Poosh does not include five guidelines, all included in the terms and conditions of WWOOF Portugal, namely, “principle for sharing and exchange”, “platform’s law obligation duty”, “commitment to an automatic or associated agreement”, “security measure for platform users”, and “data protection measure on the platform”.

Of these guidelines, the last two stand out, which are in the “security and privacy” category and which refer, respectively, to the fact that the platform informs that it verifies the identity of users and that the platform specifies the technologies used and the procedures adopted to ensure the privacy of user data.

It is also worth noting that some of the guidelines in the “security and privacy” category are present in all platforms’ documents, but the guidelines “security measure for platform users” and “data protection measure on the platform” are not among the main concerns of the platforms, according to the analyzed documents. In fact, these two guidelines are among the least representative, as far as the number of identified segments is concerned.

Another guideline in the “security and privacy” category that does not assume a leading role is “user responsibility for data”. This guideline establishes that users are responsible for controlling and protecting their data, as well as respecting the other users’ data and the platform, and are not authorized to reproduce this data.

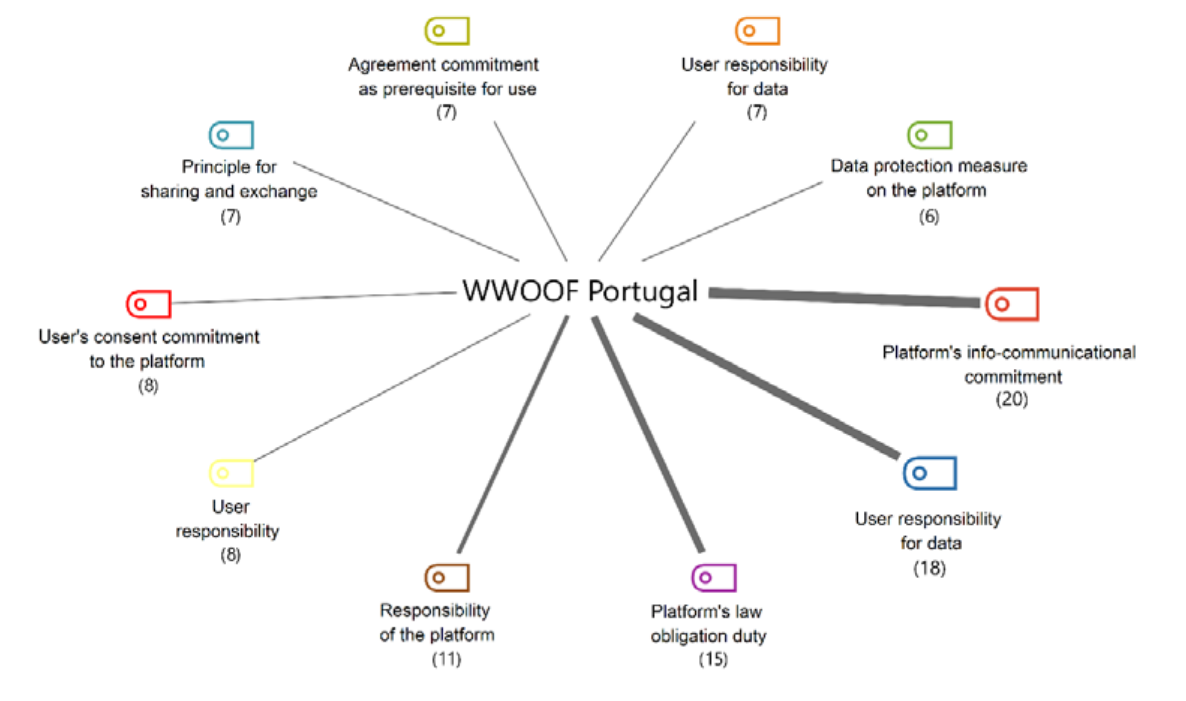

Under WWOOF Portugal’s terms and conditions, the main guidelines are: “platform’s info-communicational commitment”, “responsibility for data use by the platform” and “platform’s law obligation duty” (Figure 7).

In the segments coded under the guideline “platform’s info-communicational commitment”, WWOOF Portugal is committed and is available to inform and communicate transparently about its activities, features, and changes, for example: “our data protection officer is (name of the manager) who can be contacted via the Contact Us form”; “to enforce any of the foregoing rights or if you have any other questions about Our Site or this Privacy Policy, please contact Us using the details set out in section 14 below”; “we’ve provided additional details about the information we collect and how we use that information. We’ve also explained your choices and the control you have over your information”25.

Responsibility for the use of data is also constantly referenced in this platform’s regulatory documents, which assumes and informs about the treatment (use, handling, storage, or transfer) of the users’ data. In the segments coded under this guideline, there are statements such as “all personal data is stored securely in accordance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) (GDPR)”; “with your permission and/or where permitted by law, We may also use your data for marketing purposes which may include contacting you by email AND/OR telephone AND/OR post with information, news and offers on Our services”26.

WWOOF Portugal recognizes its obligations by law in several parts of the regulatory documents, especially regarding the GDPR, valid in Europe: “under GDPR we will ensure that your personal data is processed lawfully, fairly, and transparently, without adversely affecting your rights”27.

WWOOF Portugal is the only platform that includes all the guidelines of the “security and privacy” category. The platform shows more concern regarding the specification of technologies and procedures used to ensure the security, privacy, and treatment of user data, ensure user accountability to control and protect their data, as well as to respect other users’ data and the platform.

Intersections and Distinctions Between Platforms

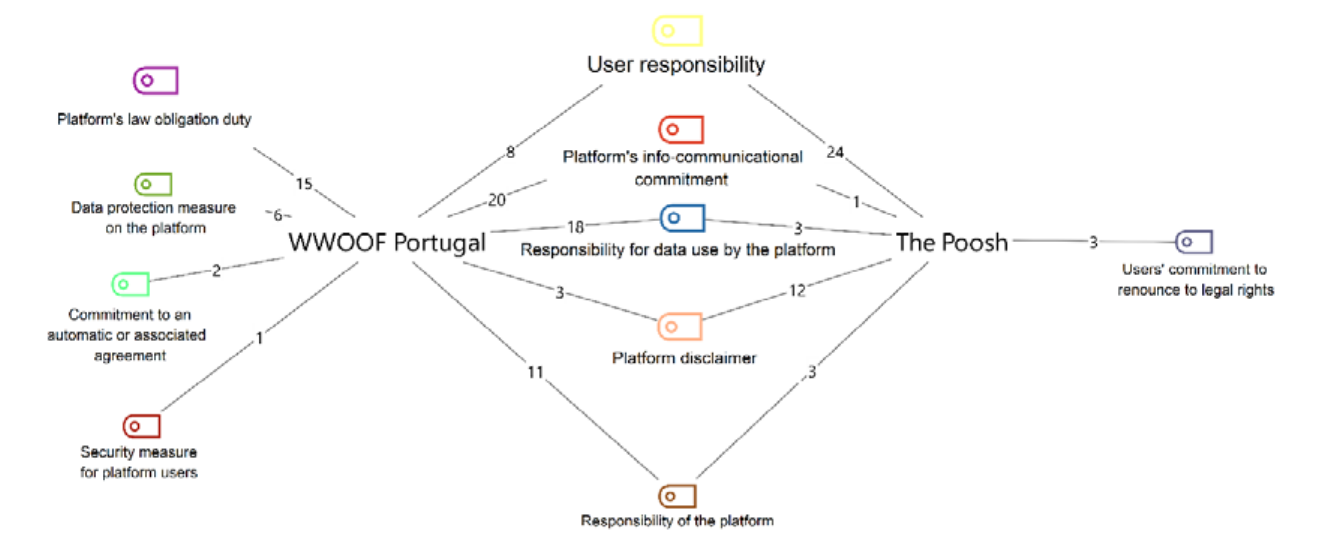

Comparing WWOOF Portugal and The Poosh (Figure 8), five guidelines are commonly considered by these platforms, even if with different preponderances if we consider the segments coded. In this way, the disparity in the guideline “platform’s info-communicational commitment” can be highlighted, with 20 segments encoded in WWOOF Portugal documents and only one encoded in The Poosh.

The guideline “platform’s law obligation duty” is also among those that encode the largest number of segments in WWOOF Portugal documents, with 15 encodings, not being considered at all by The Poosh. Another surprise found in this comparison is the absence of the “principle for sustainable practices”, concerning the platforms’ presentation of fundamentals relating the experiences with the environmentally sustainable practices promoted.

This could be a more explored guideline to ensure users’ involvement in a common good. After all, these platforms are dedicated to exclusively promoting experiences of sharing collaborative lifestyles in sustainable contexts. This guideline appeared in three segments in the documents of WWOOF Portugal and only once in The Poosh’s terms and conditions, which is why it did not receive any emphasis on the analyzes.

The only guideline not covered by WWOOF Portugal was the “users’ commitment to renounce to legal rights”, a very questionable guideline, identified in The Poosh documents (Figure 8). This guideline aims to impose on the users the commitment to renounce to their legal rights, as in the case of legal proceedings against the platform or third parties connected to it The Poosh raises this question when it states, for example, the following: “you agree that you will not seek damages of any kind from thePOOSH.org, or the principals of thePOOSH.org, or from other members of thePOOSH.org”28.

Comparing WWOOF Portugal and Volunteers Base, the discrepancies are less pronounced (Figure 9). However, there are a greater number of guidelines not mentioned by Volunteers Base. Two of these guidelines are relevant in WWOOF Portugal documents, namely “responsibility for data use by the platform” and “platform’s law obligation duty”. The importance of this last guideline was previously clarified, being only relevant to emphasize the omission of the guideline “responsibility for data use by the platform” by Volunteers Base.

Volunteers Base does not assume or inform the user about data processing, which is relevant considering that all countries are concerned with data protection and security regulation on the internet. Moreover, being an organization that uses a digital platform to mediate experiences sharing.

Conclusions

To identify a set of guidelines for building trust in the sharing of collaborative lifestyles digitally mediated by platforms that promote experiences in sustainable contexts, this study identified 20 guidelines, in three categories: “practices and conducts”, “conditions”, and “security and privacy”. These guidelines can guide users and platforms in the construction of digitally mediated sharing relationships transparently and reliably.

The construction of trust, from the perspective of this analysis, involves issues related to the treatment of users’ data, the functionalities of the sites, the relationships built between users, and the importance of platforms’ responsibilities as mediators. These topics are guiding the creation of a set of practices and conducts, based on building trust between users and platforms.

Besides, the debate about regulatory documents, and their adequacy, must be constant, since it is necessary to elaborate or improve users’ recommendations. Only half of the identified guidelines were used by all platforms, being the following common to all the three: “principle of transparency”, “financial and commercial principle”, “principle of respect and human rights”, “responsibility of the platform”, “platform disclaimer”, “platform info-communication commitment”, “user info-communicational commitment”, “platform autonomy rights”, “user’s consent commitment to the platform”, and “user responsibility for data”.

According to the guidelines identified in platforms’ documents, user data processing is an issue with a great impact on trust-building. In fact, this is a recurring issue that has been driving governance and legislation for the internet in all countries. It is commendable to note that two of the platforms studied seek to fulfill the obligations imposed by law.

However, it is necessary to emphasize that only one of the platforms mentions the existence of an official document of this kind (such as the GDPR, in Europe). Therefore, there is a lack of recognition of a legal document aimed at guaranteeing the rights of users and the duties of platforms.

The recognition of the obligations and the law to which platforms are subject can bring greater credibility and confidence. That way, users will perceive platforms as more transparent and serious and will have a better understanding of the legal security and protection framework to which the platform is linked.

In general, the carried-out analysis corroborates the idea that digital platforms for collaborative lifestyles in sustainable contexts recognize the importance of having recommendations to promote a reliable relationship with their users and among their users. However, this does not mean that the guidelines recommended by these platforms are complied with and monitored.

This study can also be useful to platforms’ managers and governmental institutions. The development of a good practice code between platforms and users of the sharing economy, would consolidate the sharing of collaborative lifestyles and, consequently, support platforms acting.

In governmental management, this study can be considered in a possible future revision of the legislation by competent institutions and for the elaboration of governance instruments that assist in the fulfillment of the rights and obligations of users and platforms.

For future studies can be assessed the degree of importance of these guidelines in the perception of managers and platform users. It is also possible to apply the same methodology to investigate the reality of other platforms and contexts.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by University of Aveiro, with PhD grant awarded to Raissa Karen Leitinho Sales (BD/REIT/8709/2019).

REFERENCES

Adali, S., Escriva, R., Goldberg, M. K., Hayvanovych, M., Magdon-Ismail, M., Szymanski, B. K., Wallace, W. A., & Williams, G. (2010). Measuring behavioral trust in social networks. In 2010 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (pp. 150-152). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISI.2010.5484757 [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo (L. A. Reta & A. Pinheiro, Trad.). Edições 70. (Trabalho original publicado em 1977) [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. (2004). Amor líquido: Sobre a fragilidade dos laços humanos (C. A. Medeiros, Trad.). Zahar. (Trabalho original publicado em 2003) [ Links ]

Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2011). O que é meu é seu: Como o consumo colaborativo vai mudar o nosso mundo (1.ª ed.; R. Sardenberg, Trad.). Bookman. (Trabalho original publicado em 2010) [ Links ]

Chan, J. K. H., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Sharing space: Urban sharing, sharing a living space, and shared social spaces. Space and Culture, 24(1), 157-169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218806160 [ Links ]

Chen, X., Proulx, B., Gong, X., & Zhang, J. (2013). Social trust and social reciprocity based cooperative D2D communications. In Proceedings of the fourteenth ACM international symposium on mobile ad hoc networking and computing (pp. 187-196). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2491288.2491302 [ Links ]

Cheshire, C. (2011). Online trust, trustworthiness, or assurance? Daedalus, 140(4), 49-58. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00114 [ Links ]

Chuang, L., He, J., & Chiu, S. (2018). Understanding user participantion in sharing economy services. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan (ICCE-TW) (pp. 1-2). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCE-China.2018.8448712 [ Links ]

European Union. (2018). Rural areas and the primary sector in the EU. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/eu-rural-areas-primary-sector_en.pdf [ Links ]

Floridi, L. (Ed.). (2015). The onlife manifesto: Being human in a hyperconnected era. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04093-6 [ Links ]

Fogg, B. J. (2003). Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. Elsevier. [ Links ]

Gray, D. E. (2014). Doing research in the real world (1ª ed.). Sage. [ Links ]

Hang, C.-W., Wang, Y., & Singh, M. P. (2009). Operators for propagating trust and their evaluation in social networks. In AAMAS ‘09: Proceedings of The 8th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems - Volume 2 (pp. 1025-1032). International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems. https://doi/10.5555/1558109.1558155 [ Links ]

Igarashi, T., Kashima, Y., Kashima, E. S., Farsides, T., Kim, U., Strack, F., Werth, L., & Yuki, M. (2008). Culture, trust, and social networks. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11(1), 88-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00246.x [ Links ]

Jiang, W., Wang, G., & Wu, J. (2014). Generating trusted graphs for trust evaluation in online social networks. Future Generation Computer Systems, 31(1), 48-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2012.06.010 [ Links ]

Kamal, P., & Chen, J. Q. (2016). Trust in sharing economy. In Proceeding of the 20th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS 2016) (pp. 1-13). Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2016/109 [ Links ]

Lee, Z. W. Y., Chan, T. K. H., Balaji, M. S., & Chong, A. Y. (2018). Why people participate in the sharing economy: An empirical investigation of Uber. Internet Research, 28(3), 829-850. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-01-2017-0037 [ Links ]

Luhmann, N. (2005). Confianza (A. Flores, Trad.). Anthropos. (Trabalho original publicado em 1979) [ Links ]

Lutz, C., Hoffmann, C. P., Bucher, E., & Fieseler, C. (2018). The role of privacy concerns in the sharing economy. Information, Communication & Society, 21(10), 1472-1492. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1339726 [ Links ]

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I [ Links ]

Sales, R. K. L., Baldi, V., & Amaro, A. C. (2020). Idealização de um modelo para compreensão da construção da confiança nas plataformas da economia de partilha. In J. C. F. Benítez (Ed.), Estudios multidisciplinarios en comunicación audiovisual, interactividad y marca en la red (pp. 178-196). Egregius. [ Links ]

Santos, G. E., & Prates, R. O. (2018). Evaluating the PROMISE framework for trust in sharing economy system. In IHC 2018: Proceedings of the 17th brazilian symposium on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-11). Association for Computing Machinery. [ Links ]

Shirky, C. (2011). A cultura da participação: Criatividade e generosidade no mundo conectado (C Portocarrero, Trad.). Zahar. (Trabalho original publicado em 2010) [ Links ]

Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. Guilford press. [ Links ]

Stern Strategy Group. (2015, 18 de setembro). Rachel Botsman: Transformation in how we think about trust [Vídeo]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ced159PQu4I [ Links ]

TED. (2016, 7 de novembro). We’ve stopped trusting institutions and started trusting strangers | Rachel Botsman [Vídeo]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GqGksNRYu8s [ Links ]

Tian, X.-F., Wu, R.-Z., & Lee, J.-H. (2017). Use intention of chauffeured car services by O2O and sharing economy. Journal of Distribution Science, 15(12), 73-84. http://doi.org/10.15722/jds.15.12.201712.73 [ Links ]

Wang, W., Qiu, L., Kim, D., & Benbasat, I. (2016). Effects of rational and social appeals of online recommendation agents on cognition- and affect-based trust. Decision Support Systems, 86(1), 48-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2016.03.007 [ Links ]

Wu, J., Ma, P., & Xie, K. L. (2017). In sharing economy we trust: The effects of host attributes on short-term rental purchases. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(11), 2962-2976. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2016-0480 [ Links ]

Yang, S.-B., Lee, K., Lee, H., Chung, N., & Koo, C. (2016). Trust breakthrough in the sharing economy: An empirical study of Airbnb. In Proceeding of the 20th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS 2016) (pp. 1-8). Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2016/131/ [ Links ]

Ye, T., Alahmad, R., Pierce, C., & Robert, L. P., Jr. (2017). Race and rating on sharing economy platforms: The effect of race similarity and reputation on trust and booking intention in Airbnb. In ICIS 2017 Proceedings (pp. 1-11). AIS. https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2017/Peer-to-Peer/Presentations/4/ [ Links ]

Yoon, Y. S., & Lee, H.-W. (2017). Perceived risks, role, and objectified trustworthiness information in the sharing economy. In 2017 Ninth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN) (pp. 326-331). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUFN.2017.7993803 [ Links ]

Zhang, Z. & Wang, K. (2013). A trust model for multimedia social networks. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 3(4), 969-979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-012-0078-4 [ Links ]

Received: September 02, 2020; Accepted: February 01, 2021

texto em

texto em