Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicação e Sociedade

versão impressa ISSN 1645-2089versão On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.39 Braga jun. 2021 Epub 30-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).3177

Articles

Journalism in State of Emergency: An Analysis of the Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemics on Journalists’ Employment Relationships

iInstituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

A condição socioprofissional dos jornalistas tem sofrido profundas transformações ao longo das últimas décadas. Estas têm origem numa sucessão de crises que afetam a comunicação social no contexto de um processo combinado de liberalização e digitalização. Além de mudanças nas rotinas de produção, as redações jornalísticas sofreram operações de reestruturação, responsáveis pela recomposição da sua força de trabalho. Entre despedimentos coletivos, aumento do desemprego, contratos a prazo, “recibos verdes”, formas descontínuas e intermitentes de trabalho, baixos salários, trabalho gratuito e a reduzido custo de estagiários, a precariedade passou, aos poucos, a caracterizar a condição jornalística. A partir dos resultados do “Estudo Sobre os Efeitos do Estado de Emergência no Jornalismo no Contexto da Pandemia Covid-19”, este artigo pretende analisar as implicações destas políticas nas relações de emprego dos jornalistas. O objetivo principal é compreender em que medida é que a resposta das empresas de comunicação social a esta nova realidade representa uma reversão da lógica de precarização ou, pelo contrário, a sua aceleração. O estudo pretende, em primeiro lugar, realizar um diagnóstico das relações de emprego antes da declaração de estado de emergência (DEE) - entre março e abril de 2020 - nomeadamente a incidência de vínculos temporários e a sua relação com fatores como o género ou a idade. Num segundo momento, analisar-se-á os efeitos da DEE a este nível, principalmente no que respeita ao recurso a contratos temporários, a despedimentos ou ao lay-off.

Palavras-chave: desemprego; jornalismo; lay-off; pandemia covid-19; precariedade

The socio-professional condition of journalists has undergone profound changes over the past few decades. These result from a succession of crises that have affected the media in the context of a combined process of liberalization and digitalization. In addition to changes in production routines, newsrooms underwent restructuring operations, responsible for the recomposition of their workforce. Between collective redundancies, increased unemployment, fixed-term contracts, “green receipts”, discontinuous and intermittent forms of work, low wages, free work and low cost of interns, precariousness began, step by step, to characterize the journalistic condition. Based on the results of the “Study on the Effects of the State of Emergency on Journalism in the Context of Pandemic Covid-19”, this article aims to analyse the implications of these policies on journalists’ employment relations. The main objective is to understand to what extent media companies’ response to this new reality represents a setback of the logic behind precariousness or, on the contrary, its acceleration. The study aims, firstly, to produce a diagnosis on employment relationships before the state of emergency declaration (SED) - between March and April 2020 -, namely the incidence of temporary modalities and their relationship with factors such as gender or age. At a second step, the consequences of SED at this level will be analysed, mainly with regard to the use of temporary contracts, dismissals or lay-offs.

Keywords: unemployment; journalism; lay-off; pandemic covid-19; precariousness

Introduction

The intersection between the processes of economic liberalisation and the processes of digitalisation in recent decades has led to an ongoing disorganisation and reorganisation of the media, with far-reaching consequences for journalism and its professionals. On the one hand, deregulation and privatisation policies, alongside the transformations in the information processes resulting from the digital turn, have undermined or shattered the economic viability of traditional media organisations whose revenue came from advertising and sales. On the other hand, computer networks and the internet have eroded journalists’ prerogative to select, process and disseminate information. Journalism and journalists have come under a permanent state of disruption caused by the shift in objectives and the system of resources and rules that defined both the old and the new media organisations, the former facing hardship or a slow disintegration and the latter constrained by a mere conformity with the technological processes and market opportunities afforded by the digital world.

Digital capitalism has become the economic force that drives and guides the media, constraining journalists and journalistic activity. Against this background, here but briefly sketched, the “normal” socio-professional condition of journalists - normal in the sense of customary - is characterised by collective redundancies, rising unemployment, fixed-term contracts, discontinuous and intermittent forms of work, low wages, unpaid or low-paid work for interns, in short, by the trappings of precarity. What effects did the covid-19 epidemic have, during the 6 weeks under the state of emergency declaration (hereafter SED), between March and April 2020, in Portugal, on the precarity “epidemic”? Did it bring about a new wave of unemployed journalists? Did it affect new sectors of journalism professionals? Did the lay-off measures make journalists even more destitute? These were the guiding questions for the present article, dictating the structure for the sections that follow.

We begin by outlining the key elements, both theoretical and empirical, that enable us to understand the trend towards precarity among journalists.

We then interpret the data on the socio-professional condition of journalists collected through a questionnaire designed in the context of the “Research of the Effects of the State of Emergency on Journalism in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic”. The analytical plan is structured so as to compare the data for the period prior to the March 2020 DEE with those that emerged in its wake, and thus register the changes that took place in this period. We thus seek to grasp the full meaning of the statistical data available, as framed by the confluence of the covid-19 epidemic and the precarity epidemic.

Media, Digital Capitalism and Precarity Among Journalists

For at least the past 2 centuries, the work of journalists has been carried out within institutions known as “the media” (Schmidt, 2020). All institutions are situated at an intermediate level between the major social, economic and political trends and the concrete behaviours and experiences that take place in such institutions. They have rules and procedures embedded in organisational, financial and professional resource structures that seek to achieve pre-established goals and which condition the profiles, forms of labour and practices of their workers. The media are institutions that belong both to the world of culture and to the world of the economy: they are part of culture because they create symbolic and cultural forms of organising society’s experience; of the economy inasmuch as they seek to earn profit in the market. The macro trends of liberalisation and digitalisation have contributed to the reconfiguration, at the meso level, of the media regime and its institutions, and at the micro level, of journalistic practices. The major trends of liberalisation and digitalisation, together but also in mutual tension, have contributed to a new venture of capital: the exploitation of all the economic potential of digitalisation, as part and parcel of a global capitalism that has been asserting itself since the last quarter of the 20th century.

What we might call digital capitalism is the manifestation of a kind of economic rationality that seeks profit by freeing it from all possible constraints across all spheres of knowledge, information, entertainment and any other field amenable to digital conversion. The growth of journalistic and informational content (or a mixture of both) as commodities, on the one hand, and the growth of the consumption of such products, on the other, have thus become the constituent ground for communication companies in the new media regime. Any value judgement is merely quantitative and applied indiscriminately across all levels of the information process, ruling out any notion of limitations. Driven by this kind of economic rationality and by the attendant technological innovations in the digital field, former media companies and institutions have been brought to ruin, while others tried to recreate themselves while new media and information agents came to the fore. Labour precarity is one of its cornerstones.

The concept of precarity has been the subject of a variety of theoretical approaches. Although these may not necessarily express antagonistic views, their different angles have contributed to the lack of a univocal meaning of the term. Alongside an ontological and existential notion, tied to the inherently contingent nature of the human condition, the term is commonly associated with the proliferation of new forms of temporary contracts as a result of the deregulation of labour laws, which includes simplified dismissal procedures, wage cuts and an increase in working hours. Without necessarily contradicting this diagnosis, some studies address the strategic slant of this process, that is to say, they see precarity not as the exception but rather as one of the foundations of the economy, one which global capital has been laying since the last decades of the 20th century. Seen in this light, to maintain a framework of risk and uncertainty can be considered not only as a way of adapting the labour force to the circumstances of the labour market, but as an orientation intrinsic to an effective and productivist labour force governance (Lorey, 2015). From another angle, this means that workers have become “entrepreneurs”, and the worker’s inner life is permeated by entrepreneurial discourse in order to change his or her know-how and place them entirely at the service of production, which in turn leads to a fragmentation and individualization of the labour force. Other analyses have focused on the emergence of a political subject, the precariat, which manifests itself in new forms of mobilisation and collective action (Armano et al., 2017). In the present investigation, the concept of precarity refers, somewhat more narrowly, to the articulation between the increase and diversification of journalists under temporary contracts, redundancies, rising unemployment and low wages.

The crisis in the print press since the beginning of the millennium, reflected in the downward trend in the number of copies sold (Fidalgo, 2008), is one of the results of the information dumping caused by the growth in digital editions (not all of which are news outlets) and exacerbated by the 2008 global economic crisis and the 2011 sovereign debt crisis and the consequent implementation, in Portugal, of a structural adjustment plan devised by the Troika (International Monetary Fund, European Commission, European Central Bank). The bankruptcy of some media organisations and the development of corporate restructuring processes are the outcome of revenue losses associated with the drop in domestic consumption and the crisis in other sectors, particularly banking and advertising (Silva, 2015; Sousa & Santos, 2014). The new regime, with its attendant economic horizon, continuous technological innovation, changes in business model and a whole new framework in terms of the modes of production, publishing and dissemination of information, has plunged the media into a state of turbulence. The latter has heightened the tendency towards a commercial view of the press and the urge to take advantage of the emergent opportunities offered by digitalisation (Garcia et al., 2020). The profession of journalist, which has always been embedded in the media, cannot remain unscathed by these processes, and the same goes for its practices.

In Portugal, against the background we have just outlined, journalism has undergone major changes, among them those that affect socio-professional and employment conditions, shaped by the trends that have generated the phenomenon of precarity. Its effects mean there is a growing percentage of journalists under temporary contracts, since collective dismissals tend to target professionals with established careers and higher wages (Baptista, 2012).

An Outline of Precarity Among Portuguese Journalists

In 1982, the “I Congresso dos Jornalistas Portugueses” (I Congress of Portuguese Journalists) mentions in its conclusions the need to counter “companies’ systematic recourse to collaborators, which restricts access of new candidates to the profession as well as the access of professional journalists to jobs”, as well as to “fixed-term contracts and other more or less disguised forms of exploitation of journalists, namely those that require the provision of services incompatible with legally established professional functions” (I Congresso dos Jornalistas, 1982, pp. 19-20). This statement stems from the increased use of this new contractual arithmetic which, according to figures released at the time by the Journalists’ Union (Sindicato dos Jornalistas; SJ), regulated the labour condition of around 10% of the editorial staff (Sindicato dos Jornalistas, 1981).

The first survey of journalists, in 1990, confirmed a scenario close to the SJ had presented a few years earlier. Although most journalists found themselves in a stable professional situation, framed by collective labour contracts (45.5%) and work agreements (27.7%), a smaller but still significant proportion was under individual contracts (19.4%), and most of these under fixed-term contracts, while some had no contract at all (7.3%; Garcia & Castro, 1993, p. 106). The figures also pointed to a profession stratified along age and gender lines. Women and younger people were primarily in a position of aspiring to a career or taking their first steps in it, earning lower wages, up to 90,.000 escudos (€450). On the opposite pole, older, male journalists tended to hold higher paid leadership and management positions (Garcia & Castro, 1993, pp. 107-108).

The segmentation we have just outlined did not suffer significant changes over the years. A second study conducted in 1997 would confirm this data, for example, a higher number of women, and more highly educated and lower-paid individuals among the younger segments of journalists (Garcia & Silva, 2009). While these conditions were often the initial stages of a progressing career, along which a greater stability would eventually be reached, the use of service contracts (“green receipts”, as they are commonly referred to in Portugal) and interns became increasingly common. The “proliferation of precarious employment situations”, as can be read in the resolution of the “III Congresso dos Jornalistas” (III Congress of Journalists), aims to “make effective and permanent employment relationships cheaper and more precarious” and is thus responsible for “situations of intolerable injustice and dependency for many journalists, which undermine the very principle of the Freedom of the Press” (III Congresso dos Jornalistas, 1998, p. 63). The document also denounces “the exploitation of intern labour, and we regard its regulation as a matter of urgency, a decisive step towards an effective professionalisation of the candidates” (III Congresso dos Jornalistas, 1998, p. 63).

This phenomenon would become more evident as soon as the first signs of the crisis in the news media emerged - a crisis which, as mentioned above, has worsened in recent years. In the period from 2004 to 2009, the percentage of interns in newsrooms rose from 5.4% to 9.2%, a trend that is in contrast with that of professional journalists, whose numbers are dwindling (Rebelo, 2011, p. 57). The results of a research into the condition of young journalists in Portugal confirm this trend, the aim of which appears to be far from restricted to a pedagogical sphere (Garcia et al., 2014). Virtually every respondent, all of which were under 38 years of age, completed at least one internship. A large portion of them (35%) repeated the experience, completing two or more internships. At the same time, half of the respondents were unemployed or had a precarious employment relationship - the service provision regime being the most prevalent. This, however, was not the result of a choice but reflected rather, in most cases, a difficulty in obtaining an employment contract (Garcia et al., 2014. p. 14).

Although the research focused on a younger population, the data obtained points to the media companies’ systematic use of temporary contracts, which is by no means a specifically national trait. The growing precarity among journalists is a phenomenon that extends beyond national borders, part and parcel of a global transition towards a post-industrial and digital model of organisation of the profession, the aim of which is to reduce it “to a simple form of labor, where journalists (from the perspective of management) are cast as flexible, multiskilled and highly moveable newsworkers” (Deuze & Fortunati, 2010, p. 118).

More recent research, based on surveys of journalism professionals, indicates that almost 50% of the labour force is under temporary contracts and/or more than half earn a monthly salary of €1,000 or less (Cardoso & Mendonça, 2017; Miranda & Gama, 2019). Previously restricted to younger journalists, job insecurity no longer defines a specific segment but extends to other age groups and categories.

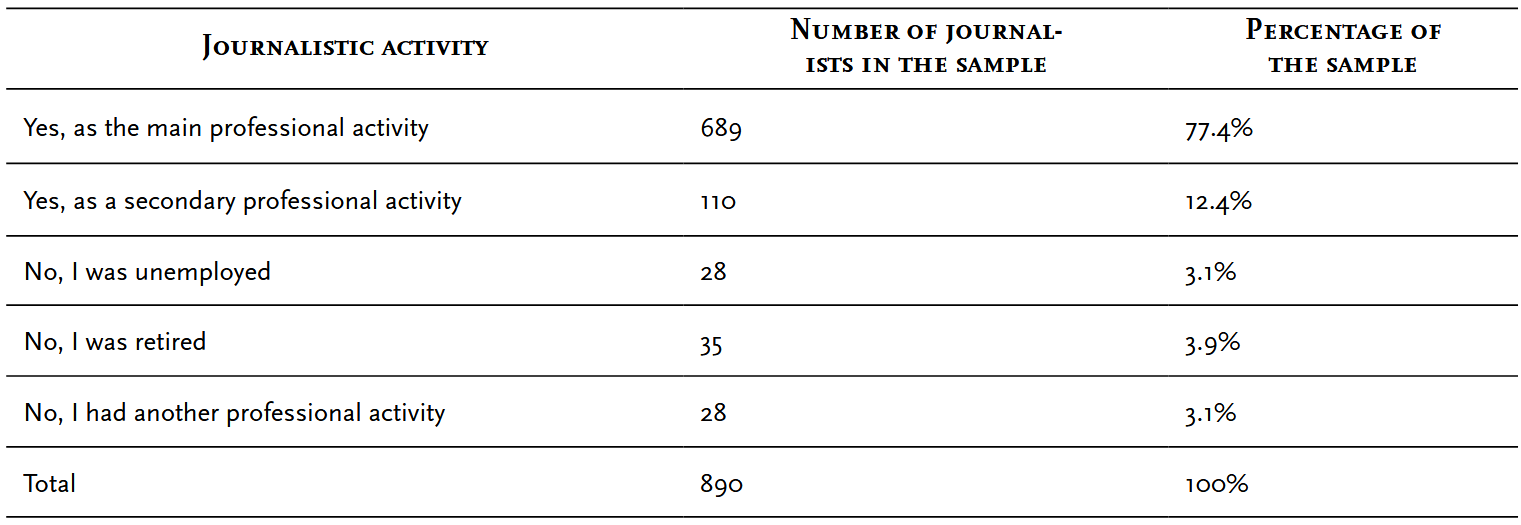

According to the data from the “Research of the Effects of the State of Emergency on Journalism in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic”, at the time a large portion of the population surveyed (see Table 1) had journalism as their main activity, and of these most were aged 41 or older (62%). However, one should underline the fact that there are 12.4% of respondents, generally men over 50 years of age, that combine the profession with some other type of paid activity; there are also 3% of unemployed, a figure below the national unemployment rate in March of that year, which stood at 6.2% (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2020). It is also important to note that more than half of the unemployed journalists (28% of the respondents) were between 51 and 70 years of age. Within this group, the proportion of female journalists, on the one hand, and of those without a university degree, on the other, is slightly higher than that found in the sample used in the present article.

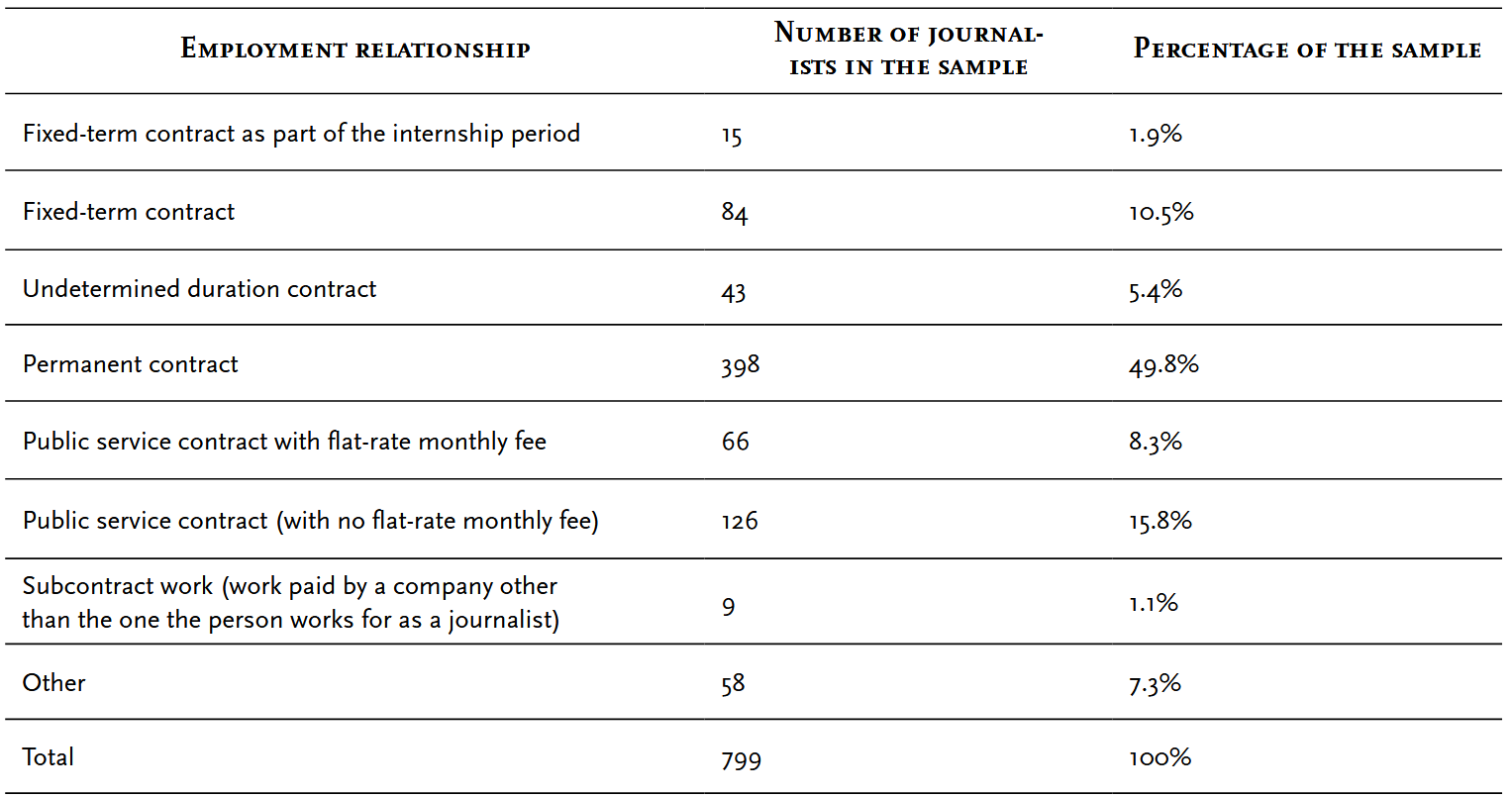

Only half of the respondents, about 50% (see Table 2), had a permanent employment contract, which confirms the previously described employment relationship framework. The number of journalists under temporary contracts is also close to this figure, and among these the most prevalent are those under a provision of services regime, with and without a flat-rate monthly fee. This type of employment relationship, in turn, is at odds with its objectives on the legal plane, for example, the regulation of the status of freelancer. According to the data, 35.5% see it as a lesser evil given the difficulty of obtaining an employment contract; and 20.8% admit that, in practical terms, their employment relationship fits into the framework of a dependent employment regime2. Of these, more than half (63% and 52.5%) were aged between 41 and 70.

Table 2 Employment Relationship at the Time of the DEE of the 799 Journalists Who, in the Sample, Declared That Journalism Was Their Main or Secondary Activity

The composition of the universe of precarious journalists is indicative of the scale of this type of contract. Although the proportion of professionals in the permanent staff of companies who have completed a higher education degree, around 63%, is higher than those under fixed-term contracts or service provision regimes with similar educational levels, the figures for the latter are not substantially lower - still over 50%. One should also register the fact that temporary employment relationships extend to most age categories. For example, of the 10.5% who are under fixed-term contracts, 60% are aged 41 or over, a figure which rises to around 69% for journalists under a service provision regime (with and without a flat-rate monthly fee).

The questionnaire also shows that the extension of temporary contracts is equally visible in the data concerning professional status. The results of the survey show that there are journalists holding editorial and administrative posts for a fixed or uncertain term and under service provision: 27.5% of editors and section editors and 25.6% of editors-in-chief and deputy editors-in-chief. Even among the members of the editorial board - all of whom are men, in other words, there is not a single case of a female respondent in this category - 24.3% are under temporary contracts.

These data, then, call into question the definition of precarity as something exceptional or “atypical”, a qualifier that emerged in the context of the first analyses of the phenomenon (Cerdeira, 2000; Kóvacs, 1999). Although perceived as the result of a process of labour segmentation within the company itself, it obeyed a rationale grounded on factors such as qualification. In this organisational model, built around a central nucleus of employees - whose fundamental role in the planning and management of work guaranteed them some degree of stability - there are also peripheral sectors, often under the employment of other sub-contracted companies, entrusted with less complex tasks and, therefore, with more precarious contracts and salary conditions. Although uneven, this model held the promise of success for those who developed the qualifications and skills necessary to gain access to the company nucleus, or core. These contractual modalities, if anything, operated as a means of professional integration for the younger members of staff, as an initial chapter in a career that would develop in a steady, step-by-step progression over the years.

The extension of precarity to the other functions and responsibilities in a company, including those carried out by the central nucleus, has rendered this model - and, by extension, the very idea of a career - obsolete. Its redefinition, under the sign of “portfolio career”, is symptomatic of the increase of temporary contracts - towards the permanent temporary (Beck, 2000, p. 70) - and the resultant normalisation of risk and uncertainty (Lorey, 2015).

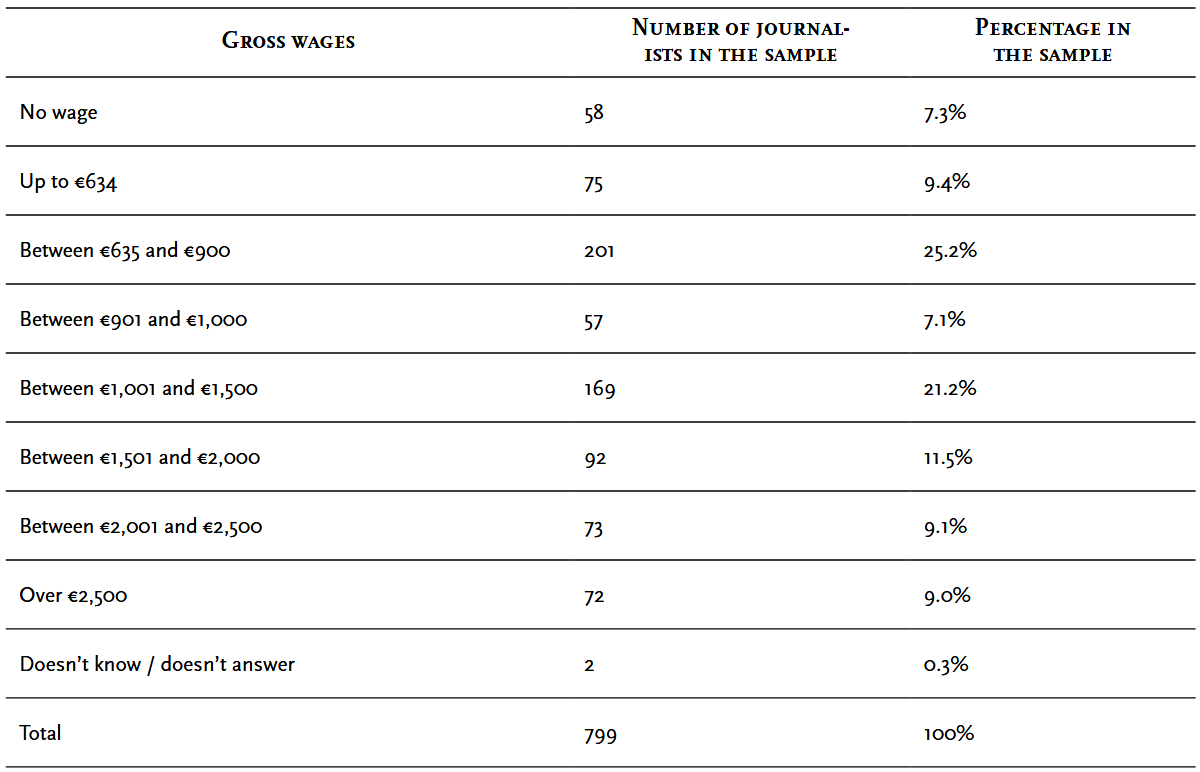

The data on wages and union membership can be interpreted as the result of this relationship. Before the DEE, as one can see from Table 3, about half of the respondents earned a wage of less than €1,000 gross per month (as shown by the research studies mentioned above), which contrasts with the 30% who earn a wage over €1,500. Crossing this data with information on the contractual relationship enables us to discern a direct correlation between the income values and the percentage of journalists on permanent contracts. Among employees earning up to €634 per month, there are only 16% of professionals on the permanent staff. However, among the journalists with an income between €1,500 and €2,000 there are 62% with a permanent contract, a figure which rises to 75% for those earning €2,001 to €2,500. Likewise, the lower the wage the greater the percentage of journalists in this kind of employment relationship.

Table 3 Gross Wages at the Time of the DEE of the 799 Journalists Who, in the Sample, Declared That Journalism Was Their Main or Secondary Activity

This correlation is not so clear in the analysis by age categories. The average age of the respondents - 47 years old - means that, except for the wage bracket between €635 and €900, both wages up to €634 and those above €1,000 are mostly to be found among journalists over 41 years of age. Although there is a correlation between an increase in age and a higher income among those earning above €1,000, it is nevertheless significant that, if one considers professionals between the ages of 51 and 70, the highest percentage of them are to be found in the category of wages of up to €634 (30.7%), between €2,001 and €2,500 (41.1%) and above €2,500 (63.9%). In terms of the relation between the wage and gender factors, taking the composition of the universe of respondents as a reference point, one notices a higher proportion of women with an income between €635 and €1,500, an equivalence in the category of those earning between €1,501 and €2,000 and a lower (though not substantially so) proportion of women among professionals with wages above the latter figure, something that may be explained by the greater difficulty of accessing management positions (Lobo et al., 2017).

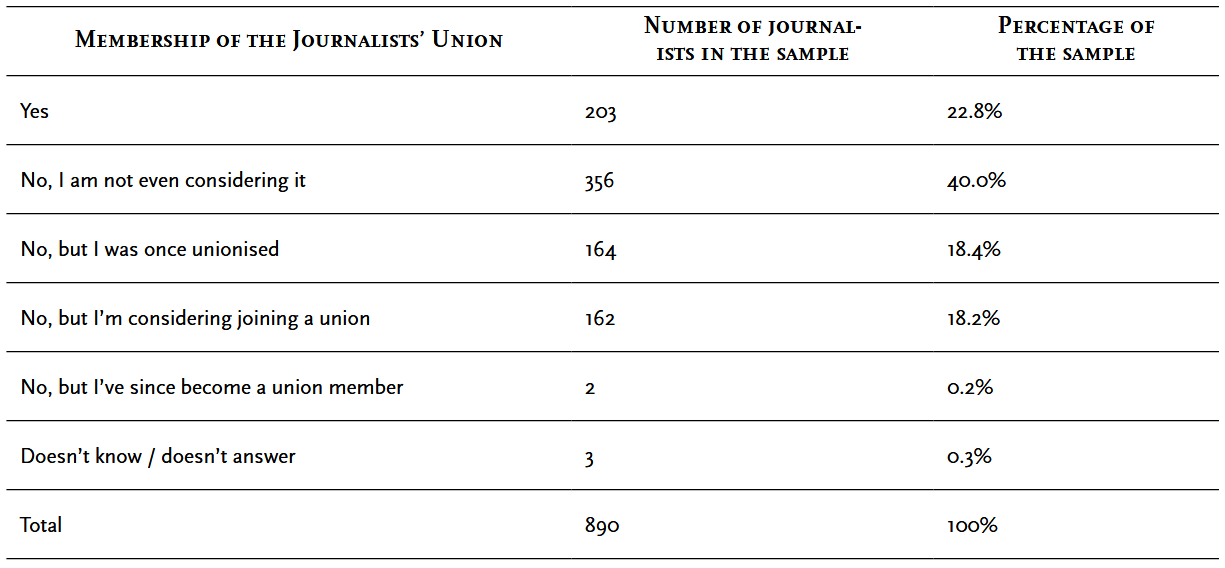

Finally, one should underline some results regarding membership of the Journalists’ Union (see Table 4). Only 22.8% of the respondents claimed to be members, while 40% say they have no intention of joining, a higher percentage than that of those who, on the contrary, are considering joining (18.2%). The majority of union members have a permanent contract (around 60%), are over 41 years old (82.8%, with 46.8% over 51) and 72.5% earn more than €1,000 (49% of these earning more than €1,500). Among those who are no longer members and those who do not intend to join in the future, the scenario is somewhat the reverse: the percentage of journalists on temporary contracts is higher (54% and 48%), the majority earn less than €1,500 in the former (62%) and less than €1,000 in the latter (56.6%). In turn, and given the increase in this kind of contractual relationship, their age composition tends to be the same as that of the sample, with an age below 50 years old (51% and 67.7%). On the other hand, it is important to note that, among those planning to join a union, there is a greater proportion of younger journalists (53% under 40), journalists on temporary contracts (around 57%), and women (42%).

Table 4 Membership of the Journalists’ Union at the Time of the DEE Among the Total of 890 Journalists That Answered the Questionnaire

The data presented are partly the result of the proliferation of temporary contracts in the newsrooms. The fact that lower wages are to be found among those who have a less stable employment situation reflects the above-mentioned framework, marked by risk and uncertainty. Fostering hope in overcoming these circumstances (Kuehn & Corrigan, 2013) or simply ensuring survival dictates a compliant attitude towards the wage conditions offered by the market, especially when there are has high levels of business concentration (Silva, 2004). Besides dictating this stance, incompatible with antagonistic demands and conducive to greater competitiveness, the various types of interdependent inequalities push forward the notion that, historically, has driven a certain kind of union action: that of a class united by its common conditions and interests. This process, moreover, is not exactly recent, nor is it exclusive to journalists, judging by the reduction in unionisation rates in Portugal and other countries (Alves, 2020; Cerdeira, 1997). At the same time, however, non-union membership seems to spring from mechanisms that induce such a practice, mechanisms that play a significant role in the transformation of newsrooms into areas of non-law (Accardo, 2007), rather than being the result of a lack of faith in the union - as suggested by the number of responses signalling a desire for future membership.

The Effects of the Declaration of the State of Emergency

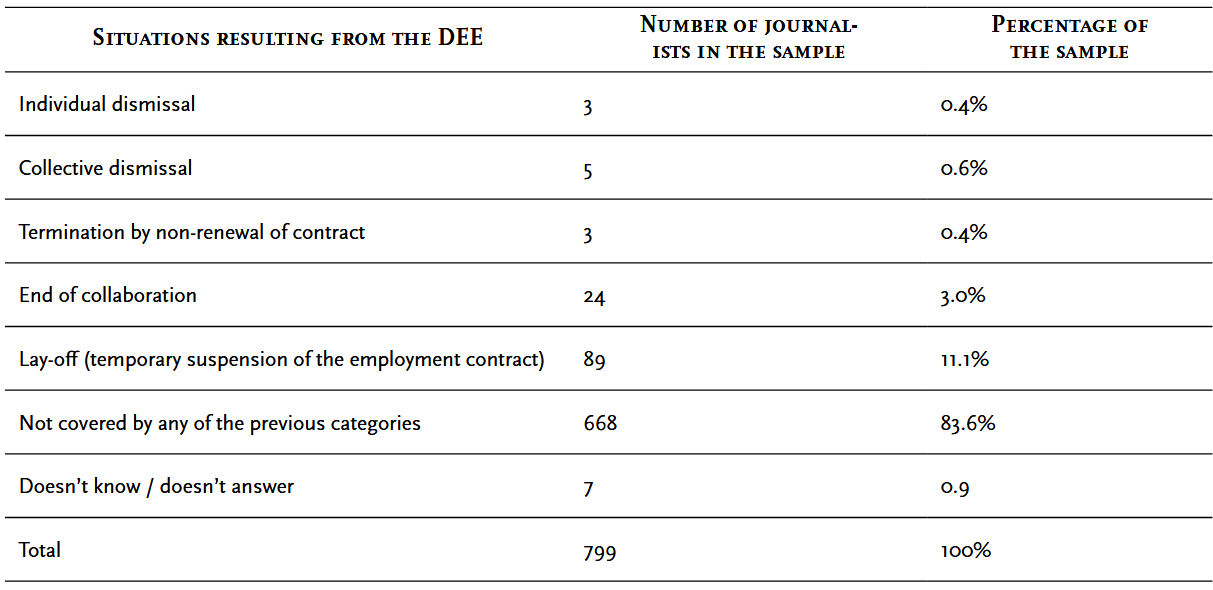

The March/April 2020 SED led to changes in the condition of 11.8% of the journalists surveyed, as shown in Table 5. The new situations resulted primarily from the application of the lay-off regime by the employers. Among those affected by this process, there is a predominance of women (44.9%).

Tabela 5 Situations Resulting From the DEE Among the 799 Journalists Who Declared That Journalism Was Their Main or Secondary Activity

The new situations in journalism result, in the second place, from the end of collaboration, a solution that applies to freelance journalists. The media sector’s economic response to the epidemic seems much the same as the type of measures adopted in other areas. Broadly speaking, these reproduce inequalities in terms of job security, or rather, employment vulnerability. The fact that workers under the service provision regime have a contractual relationship which, in theory, is comparable to that of a self-employed worker facilitates the termination of the contract in terms of both the speed of the process and its associated costs, since it does not require any compensation (Caldas et al., 2020). Only 29 journalists (3.8%) had access to some form of subsidy or social support, most of whom had a permanent contract (24.1%) or were service providers with no flat-rate monthly fee (65%). Most journalists under this regime were not entitled to the extraordinary support for independent workers and only 22% requested this mechanism. While this may be due to the fact that journalists continued to work under this scheme, the low number of recipients may also be tied to the eligibility criteria, applicable only to independent workers who have suffered a complete cessation of their economic activity or an income reduction of up to 40% in the 30 days prior to the request filed with the Social Security services (Caldas et al., 2020).

These eligibility criteria help to explain changes in the professional status of journalists after the DEE in 94 cases. Permanent contracts account for only 11.7% of this sample. Most of these journalists were under temporary contracts: provision of services (6.4%) and with no flat-rate monthly fee (19.1%), undetermined duration contract (6.4%) or fixed-term contract (7.4%), among others. One may therefore conclude that temporary contracts, since they reduce the costs of workers’ redundancies, carry fewer risks for the employer. One should also note an increase in unemployment, which makes up 17% of new employment situations. Overall, the current composition of this population in terms of working conditions is not too different from the one that existed at the time of the DEE. In terms of income, new situations mostly affect those with lower wages, more than half of which are below €900: 11.2% have no income (internships), 28% earn up to €634 and 22.9% between €635 and €900. Salaries above €1,500 account for only 11% of new cases. Of the 11 new contracts above €2,000, only three were signed by women. This shows an increase in the number of journalists with a gross monthly income of €900 or less (47%) and, at the same time, a decrease in the number of professionals with salaries above €1,000, from 50.8% to 44.2%.

Conclusion

At the end of October 2020, Global Notícias, one of the largest media groups in Portugal, which owns publications such as Diário de Notícias and Jornal de Notícias or the TSF radio station, announced the collective dismissal of 81 employees, 17 of whom were journalists. This measure, according to a press release by the Journalists’ Union, came after the media group resorted to the simplified lay-off regime (Sindicato dos Jornalistas, 2020). Although the operation is not exactly unprecedented - both in the journalist sector as a whole and in the media group itself, which resorted to similar processes in 2009 and 2014 - it reflects the worsening of media companies’ economic situation, which in turn can be explained by the succession of crises in recent years.

A crisis, however, may also present a business opportunity, an opportunity, that is, for creative destruction, to evoke Schumpeter’s (1975) infamous concept. The results of the “Research on the Effects of the State of Emergency on Journalism in the Context of Pandemic Covid-19” demonstrate the effects the restructuring and reengineering processes had on newsrooms, an effect that should be framed against the background of the structural adjustment plans dictated by the Troika. Once perceived as “atypical”, the use of temporary contracts has become increasingly common, covering a wider range and number of professionals. Precarity, then, no longer affects only the young or a handful of freelance journalists: it has become the norm in the regulation of the socio-professional status of workers with careers spanning several years and even some with editorial and management positions. This widening, as argued above, has a direct impact on the workers’ wages. The “€1,000” monthly salary, which was the mark of a younger generation - the thousand-euro generation, precisely, as it was sometimes called - takes on new forms and now defines the condition of several generations of journalists. However, these changes do not seem to incite collective action, at least through the union.

The so-called “new normal” caused by the covid-19 epidemic does not seem to have led to an inversion of this scenario. Against the background of the current economic crisis, containment policies are now also aimed at the financial health of companies; in other words, at cutting costs, by being applied to workers whose employment (or lack of it) allows for faster processes. The action launched by the Global Notícias group foreshadows a scenario that could play out in the near future.

This scenario will come about in a context where the economic-productive application of algorithmic digital technologies permeates a variety of fields, including the media. The emergence of automatic writing services, on the one hand, and the extension of a kind of piecemeal and temporary work (the gig economy), organised and managed through digital platforms, into all areas, regardless of qualification, on the other hand, foreshadow an automated and robot-like journalism, in which the worker performs increasingly subordinate functions, to the frenzied beat of the machine (Mosco, 2019).

The current routines of journalistic production are not far from this scenario of proletarianization. Besides the multiple and versatile roles journalists are forced to perform, the tendency is for these roles to be performed from inside the newsroom, racing against the clock and under constant quantitative audience measurement (Camponez, 2011; Garcia, et al., 2018; Waldenström et al., 2018; Witschge & Nygren, 2009). The reconfiguration brought about by teleworking does not seem to run counter to this logic at all (Miranda et al., 2021), while at the same time contributing to a greater isolation of journalists.

The degradation of employment and working conditions, according to the results of this research, ends up impacting on the perceptions of, and expectations towards, a career in journalism (Camponez & Oliveira, 2021). Once journalism becomes, gradually, a different kind of work, quite distinct from the profession one had or one might have at some point in the future - with no minimum guarantees in terms of financial stability and/or continuity - to abandon the profession becomes an increasingly viable hypothesis (Fidalgo, 2019; Matos, 2020; O’Donnell et al., 2016). In the end, faced with this dramatic shift, no journalism is better than one that is no journalism at all. To conclude, the covid-19 pandemic is accelerating pre-existing trends: rather than a return to normal, this calls for the normal itself to be put into question.

Referências

Accardo, A. (2007). Journalistes précaires, journalistes au quotidien. Agone. [ Links ]

Alves, P. M. (2020). Porque estão os sindicatos em crise. Seguido de algumas considerações para dela saírem. In P. P. Cabreira (Ed.), História do movimento operário e conflitos sociais em Portugal: Congresso História do Trabalho, do Movimento Operário (pp. 469-492). Instituto de História Contemporânea. https://ihc.fcsh.unl.pt/historia-movimento-operario-2020/ [ Links ]

Armano, E., Bove, A., & Murgia, A. (2017). Mapping precariousness, labour insecurity and uncertain livelihoods. Routledge. [ Links ]

Baptista, C. (2012). Uma profissão em risco iminente de ser “descontinuada”. Jornalismo & Jornalistas, 52, 15-17. [ Links ]

Beck, U. (2000). Un nuevo mundo feliz: La precariedad del trabajo en la era de la globalización. Paidós. [ Links ]

Caldas, J. C., Silva, A. A., & Cantante, F. (2020). As consequências socioeconómicas da covid-19 e a sua desigual distribuição. CoLABOR. https://colabor.pt/publicacoes/consequencias-socioeconomicas-covid19-desigual-distribuicao/ [ Links ]

Camponez, C. (2011). Deontologia do jornalismo. Almedina. [ Links ]

Camponez, C., & Oliveira, M. (2021). Jornalismo em contexto de crise sanitária: Representações da profissão e expectativas dos jornalistas. Comunicação e Sociedade, 39, 251-267. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).3178 [ Links ]

Cardoso, G., & Mendonça, S. (2017). Jornalistas e condições laborais: Retrato de uma profissão em transformação. Obercom. https://obercom.pt/jornalistas-e-condicoes-laborais-retrato-de-uma-profissao-em-transformacao/ [ Links ]

Cerdeira, M. C. (1997). A sindicalização portuguesa de 1974 a 1995. Sociedade e Trabalho, 1, 46-53. [ Links ]

Cerdeira, M. C. (2000). As novas modalidades de emprego. Ministério do Trabalho; Direção-Geral de Emprego e Formação Profissional; Comissão Interministerial para o Emprego. [ Links ]

Deuze, M., & Fortunati, L. (2010). Atypical newswork, atypical media management. In M. Deuze (Ed.), Managing media work (pp. 111-120). Sage. [ Links ]

Fidalgo. J. (2008). Os novos desafios a um velho ofício ou… um novo ofício? - A redefinição da profissão de jornalista. In M. Pinto & S. Marinho (Eds.), Os media em Portugal nos primeiros cinco anos do século XXI (pp. 109-128). Campo das Letras. [ Links ]

Fidalgo, J. (2019). Em trânsito pelas fronteiras do jornalismo.Comunicação Pública, 14(27). https://doi.org/10.4000/cp.5522 [ Links ]

Garcia, J. L., Marmeleira, J., & Matos, J. N. (2014). Incertezas, vulnerabilidades e desdobramento de atividades. In J. Rebelo (Ed.), As novas gerações de jornalistas em Portugal (pp. 9-19). Editora Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

Garcia, J. L., Martinho, T. D., Cunha, D. S., Alves, M. P., Matos, J., & Graça, S. M. (2020). O choque tecno-liberal, os media e o jornalismo. Estudos críticos sobre a realidade portuguesa. Almedina. [ Links ]

Garcia, J. L., Martinho, T. D., Matos, J. N., Ramalho, J., Cunha, D. S., & Pinho Alves, M. (2018). Sustainability and its contradictory meanings in the digital media ecosystem: Contributions from the Portuguese scenario. In A. Delicado, N. Domingos, & L. Sousa (Eds.), Changing societies: Legacies and challenges. Vol. iii. The diverse worlds of sustainability (pp. 341-361). Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Garcia, J. L., & Silva, P. A. (2009). Elementos de composição socioprofissional e de segmentação. In J. L. Garcia (Ed.),Estudos sobre os jornalistas portugueses: Metamorfoses e encruzilhadas no limiar do século XX (pp. 121-132). Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Garcia, L., & Castro, L. (1993). Os jornalistas portugueses: Da recomposição social aos processos de legitimação profissional. Sociologia: Problemas e Práticas, 13, 93-114. https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2019230.07 [ Links ]

I Congresso dos Jornalistas. (1982). 1.º Congresso dos Jornalistas Portugueses: Conclusões, teses, documentos. Secretariado da Comissão Executiva do 1.º Congresso dos Jornalistas Portugueses. [ Links ]

III Congresso dos Jornalistas. (1998). Resolução. In Sindicato dos Jornalistas. (Ed.), Gazeta: III Congresso dos Jornalistas (pp. 62-66). Sindicato dos Jornalistas. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estatística. (2020, 2 de junho). Estimativas mensais de emprego e desemprego: Em março, a taxa de desemprego situou-se em 6,2% e a taxa de subutilização do trabalho em 12,4% - Abril de 2020. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=415271422&DESTAQUESmodo=2 [ Links ]

Kóvacs, I. (1999). Qualificação, formação e empregabilidade. Sociedade e Trabalho, 4, 7-17. [ Links ]

Kuehn, K., & Corrigan, T. (2013). Hope labor: The role of employment prospects in online social production. The Political Economy of Communication, 1(1), 9-25. [ Links ]

Lobo, P., Silveirinha, M. J., Silva, M. T., & Subtil, F. (2017). In journalism, we are all men.Journalism Studies, 18(9), 1148-1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2015.1111161 [ Links ]

Lorey, I. (2015). State of insecurity: Government of the precarious. Verso. [ Links ]

Matos, J. N. (2020). “It was Journalism that abandoned me”: An analysis of journalism in Portugal. triple C: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 18(2), 535-555. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v18i2.1148 [ Links ]

Miranda, J., Fidalgo, J., & Martins, P. (2021). Jornalistas em tempo de pandemia: Novas rotinas profissionais, novos desafios éticos. Comunicação e Sociedade, 39, 287-307. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).3176 [ Links ]

Miranda, J., & Gama, R. (2019). Os jornalistas portugueses sob o efeito das transformações dos media. Traços de uma profissão estratificada. Análise Social, 54(230), 154-177. https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2019230.07 [ Links ]

Mosco, V. (2019). Labour and the next internet. In M. Deuze & M. Prenger (Eds.), Making media: Productions, practices, and professions (pp. 259-271). Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

O’Donnell, P., Zion, L., & Sherwood, M. (2016). Where do journalists go after newsroom job cuts? Journalism Practice, 10(1), 35-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1017400 [ Links ]

Rebelo, J. (2011). Ser jornalista em Portugal. Gradiva. [ Links ]

Schmidt, T. R. (2020). Rearticulating carey. Cultural institutionalism as a model to theorise journalism in time. In M. Bergman, K. Kirtiklis, & J. Siebers (Eds.), Models of communication. Theoretical and philosophical approaches (pp. 133-151). Routledge. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J. (1975). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Silva, E. C. (2004). Os donos da notícia: Concentração da propriedade dos media em Portugal. Porto Editora. [ Links ]

Silva, E. C. (2015). Crisis, financialization and regulation: The case of media industries in Portugal. The Political Economy of Communication, 2(2), 47-60. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/42239 [ Links ]

Sindicato dos Jornalistas. (1981). Escândalo não pode continuar. Jornalistas: 10 por cento são contratados a prazo. Jornalismo, 2, 10. [ Links ]

Sindicato dos Jornalistas. (2020, 6 de novembro). Lay-off não pode servir para financiar despedimentos. https://jornalistas.eu/lay-off-nao-pode-servir-para-financiar-despedimentos/ [ Links ]

Sousa, H., & Santos, L. (2014). Portugal at the eye of the storm: Crisis, austerity and the media. Javnost - The Public, 21(4), 47-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2014.11077102 [ Links ]

Waldenström, A., Wiik, J., & Andersson, U. (2018). Conditional autonomy: Journalistic practice in the tension field between professionalism and managerialism. Journalism Practice, 13(4), 493-508. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1485510. [ Links ]

Witschge, T., & Nygren, G. (2009). Journalistic work: A profession under pressure? Journal of Media Business Studies, 6(1), 37-59. http://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2009.11073478 [ Links ]

Received: January 26, 2021; Accepted: May 21, 2021

texto em

texto em