Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicação e Sociedade

versão impressa ISSN 1645-2089versão On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.39 Braga jun. 2021 Epub 30-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).3176

Articles

Journalism in Time of Pandemic: New Professional Routines, New Ethical Challenges

iCentro de Estudos Interdisciplinares do Século XX, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

iiCentro de Estudos da Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

iiiCentro de Administração e Políticas Públicas, Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

A pandemia da covid-19 e o subsequente processo de confinamento conduziram a linhas de convulsão em diferentes setores da sociedade. Marcado por um contexto de instabilidade e incerteza, onde diferentes manifestações de transformação tecnológica, económica e social potenciam novas práticas e convenções, bem como suscitam novos e renovados desafios deontológicos, o jornalismo não é exceção. Com base nas respostas de um inquérito a 890 jornalistas portugueses, o presente artigo procura mapear os efeitos do estado de emergência de março a abril de 2020 nas práticas e rotinas, e nos preceitos ético-profissionais de uma atividade que avoca uma reavivada relevância num ambiente de desinformação e “infodemia”. Mais do que revelarem novos problemas, os resultados sugerem uma acentuação dos desafios e dilemas pré-existentes. No plano das práticas, indicia-se uma domiciliação relativamente transversal da atividade. Este fenómeno é acompanhado por marcas de despersonalização do contacto com as fontes e eventos, e por sinais de isolamento social dos jornalistas. No campo ético-deontológico, sublinha-se a emergência de questões deontológicas particulares no contexto da pandemia, onde os aspetos relacionados com o rigor - rejeição do sensacionalismo, distinção clara entre factos e opiniões ou repúdio de quaisquer formas de censura -, assim como os elementos subjacentes ao contacto com as fontes, assumem especial dimensão.

Palavras-chave: deontologia; fontes de informação; redação; rotinas profissionais; teletrabalho

The covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent process of confinement led to lines of convulsion in different sectors of society. Marked by a context of instability and uncertainty, where different manifestations of technological, economic and social transformation enhance new practices and conventions, as well as raising new and renewed deontological challenges, journalism is no exception. Based on the responses of a survey answered by 890 Portuguese journalists, this article seeks to map the effects of the March-April 2020 state of emergency on practices and routines, and on the ethical-professional precepts of an activity that calls for a revived relevance in an environment of disinformation and “infodemic”. More than revealing new problems, the results obtained suggest the intensification of the pre-existing challenges and dilemmas. In terms of practices, it is indicated that the activity is relatively domiciled. This phenomenon is accompanied by marks of depersonalization of contact with sources and events, and by signs of social isolation from journalists. In the ethical-deontological field, the emergence of particular deontological issues in the context of the pandemic, where aspects related to rigour - rejection of sensationalism, a clear distinction between facts and opinion or repudiation of any form of censorship - as well as to subsequent elements underlying contact with the sources, take on a special dimension.

Keywords: deontology; news sources; newsroom; professional routines; teleworking

Introduction

Gathering information on the perceptions of Portuguese journalists about media and their profession was one of the purposes of the “Study on the Effects of the State of Emergency on Journalism in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic”, carried out through a survey applied to professionals with a license to practice. Knowing that a change in routines may have an impact on the ethical-deontological field, the survey had to assess these two areas. On the one hand, it was about understanding if there were any changes of habits and work attitudes caused by the new production environment. On the other hand, it was about gathering opinions on their effect on the professional practice, especially when it came to deontology.

The section of the survey focused on professional routines gathered questions aimed at comparing the scenario before and during lockdown, mainly the aspects directly linked to standard operating patterns. There was also a question about the relative weight of topics related to covid-19 in the set of articles developed after the state of emergency declaration (SED), on March 19, 2020.

In order to ascertain if there was an increase in teleworking, also present on other professions, there were questions about journalists’ primary workplace. Respondents were asked how often they were in actual contact with other fellow-journalists, as well as what were their thoughts about the possible use of new technological resources for the execution of their work during the state of emergency. In particular, they were asked to elaborate about the impact of this kind of resources in journalism’s future and the profession’s ethical-deontological precepts.

Concerning deontology, it focused on three aspects. In addition to a simple question about if the context that resulted from the SED raised any specific deontological issues to journalists, there was another one, requiring multiple-choice answer: which principles, values and procedures were questioned the most in media’s coverage of the state of emergency? Respondents were allowed to select up to five dimensions, from a list of 10: accuracy; independence; sources of information; contact with sources or witnesses; rectification of information; professional faults; non-discrimination; methods of gathering information; identification of protagonists in news pieces; and privacy. The survey included two more questions aimed at learning if during SED the editors or directors had asked respondents to produce pieces usually called “sponsored content” (paid by entities outside the company) and if those kinds of requests were new or had happened before.

This article presents a theoretical framework on the issues related to professional routines and deontology, focusing, afterwards, on the survey’s results, which are discussed in order to substantiate conclusions.

Signs of the Intensification of the Crisis

The respect for a set of ethical principles and values, materialised into deontological norms, was always a cornerstone of journalism, the main reason for its legitimisation as a public interest activity, free and responsible (Camponez, 2011; Fidalgo, 2009; McBride & Rosenstiel, 2014; Meyers, 2010; Plaisance, 2009; Ward, 2013; Wilkins & Christians, 2009). Ethics is where we always come back when everything seems to change in the global media landscape and in the concrete conditions for the practice of journalism: a sort of back to basics, which reminds us what it is a distinguishing mark comparing to other areas of communication in the public space. Its importance is, moreover, interlinked with journalists’ own identity affirmation, because, as Singer (2014) points out, ethical principles “are used not only to suggest how journalists should behave, but also to define what they are” (p. 49).

Although the great ethical principles that guide journalism are still basically the same, that does not mean they should not be interpreted according to concrete conditions, circumscribed in terms of the space and time in which the activity occurs. In recent decades, marked by the great technological changes that paved the way to the digital era, the debate on the new ethical and deontological challenges faced by journalists has strongly accelerated, with growing calls for the “need of new ethics for a new media ecosystem, and a new deontology for a journalism facing new challenges” (Camponez & Christofoletti, 2019, p. 5). The contexts in which journalism is currently practiced and in which media companies work are not mere bumps in the road. On the contrary, they have brought changes and ways of doing that question some of the assumptions we used to make about this activity, being evident that today it is “hard to imagine an exclusively offline journalism” (Siapera & Veglis, 2012, p. 1).

In this new scenario, there are three major aspects we can take into consideration, each one of them with an impact on the ethical reflection on journalism’s principles and practices: (a) the growing presence of digital technologies in all processes of research, elaboration, editing, and dissemination of public information about current events, with internet’s ubiquity and the immediacy of news flows; (b) the end of the journalists’ monopoly in the information process (Fenton, 2010; Ryfe, 2019), with the coming into the scene (made easier by the profusion of auto-editing and dissemination tools on a global scale) of new actors/agents and new communication networks - something that, by the way, promotes a culture of participation that blurs the boundaries between senders and receivers, and between professionals and non-professionals (Carlson, 2016; Carlson & Lewis, 2015); and (c) a severe economic crisis caused by the exhaustion of the old business model in which mass media thrived, with dramatic repercussions on media revenues and, consequently, on the opportunities of practicing journalism with independence, autonomy, and in the public interest.

(a) Although it might be dangerous (and misleading) to assess today’s journalism only on the basis of the digital technologies that shape it (Zelizer, 2019), thus believing that they alone can overcome crises and recover lost time (Lewis & Westlund, 2016), the truth is that the new digital context brought new challenges, both in terms of professional routines and in terms of ethics (White, 2014). Several studies have been carried out to identify ethical issues or dilemmas specifically concerned with online journalism, in an environment of convergence of means, techniques, supports, and formats (Deuze, 2010), with the certainty that nowadays all journalism develops in a digital environment (Friend & Singer, 2007). There seems to be a consensus on the issues raised by the new media context (Riordan, 2014) that do not find an answer in the traditional ethical codes: the pressures of the speed of information, to the detriment of accuracy and the need for verification (Fenton, 2010; Martins, 2019); the prevalence of anonymity (or the ease of creating false identities) at multiple levels, which affects the principle of transparency; the risk of taking responsibility away from journalists when it comes to hypertext, an usual tool of the digital universe; the blurring of boundaries between what is public and what is private (especially in social media), which opens the way to confusion and abuse; the increasing porosity between editorial and commercial areas, which jeopardises the fragile credibility of journalism in the face of market demands (Pickard, 2019); the constant presence of metrics and immediate feedback of the public (likes, page-views, comments, retweets…), which increasingly conditions the autonomy of editorial decision.

(b) As said before, all this takes place in the field of public information about timely events, which is no longer a journalists’ monopoly. In fact, technological innovations, accompanied by changes at social, cultural and economic levels that demand greater participation of the public in the information processes, made accessible for all what was once reserved only for some. The multiplication of cheap and technically easy auto-editing tools, together with the exponential diffusion of internet and of its access through smartphones (which made social media omnipresent), has profoundly altered the media context of our societies, again blurring of boundaries between professionals and amateurs, between producers and consumers of news, between certified information and all sorts of substitutes (Christofoletti, 2014). These deep changes, not always well digested by professionals (Singer, 2014), have brought in with them a few challenges in terms of journalists’ identity (Donsbach, 2010). In the sequence, authors such as Ward (2016, 2018) have suggested that in addition to a journalism ethics for professionals, which he considered to be pre-digital, there should be an ethics for anyone involved in the news processes. Other authors, like Friend and Singer (2007), insist that one should expect journalists to have a specific ethical set of norms, which, in fact, would be the distinguishing trademark of their professional production: the

distinction between journalism and other forms of publication rests primarily on ethics - as does, ultimately, the journalists ’ professional survival. How the journalist does his or her job will be fundamental to whether that job continues to hold any value, or even to exist at all, in a world in which anyone can be a publisher - but not necessarily a journalist. (p. 23)

(c) As a background to all this commotion, we have an economic and entrepreneurial component that gets worse by the day and affects, at many levels, the exercise of journalism and its respect for good professional practices and ethical principles. The proliferation of free online informative content, in addition to the coming into the scene of big global technological companies (Google, Facebook, YouTube), which absorb the biggest share of advertising previously invested in the media, has lessened the chances of profitability of most media companies. Furthermore, the severe decrease in the number of journalists in newsrooms, added to the fierce competition among media and to the economic pressure towards greater flexibility in mixing editorial choices and commercial propositions - for instance, the so widespread “sponsored content” (Cardoso et al., 2020; Fidalgo, 2016; Ikonen et al., 2017), - was, in many cases, responsible for lower ethical demands, which eventually had an impact on journalism’s quality and credibility. Actually, the attachment to ethical principles and the respect for deontological norms are not disconnected from the concrete, structural and cyclical conditions in which journalism is practiced (Mathisen, 2019).

This is the context where we should inscribe what happened to journalism and the media during the fight against the new coronavirus pandemic, whether we are talking of new work routines or of the ethical challenges they faced.

A Changing Professional Environment

Studies on journalism have been pointing out the impact caused by new digital and communication resources on reformatting the way information professionals work (Tong, 2017). One of the most obvious examples of this transformation of labour routines occurs in the relationship with the sources and events, where the emergence of new ways of communication made possible the use of remote and more depersonalised contact formulae (Berkowitz, 2019). Nevertheless, the technological progress that influenced Portuguese newsrooms more recently did not necessarily translate into the streamlining or benefitting of journalism practice - for instance, there were no clear signs of relocation of production sites or decrease in journalists’ workload (Pacheco & Freitas, 2014). On the contrary, one might argue that these new ways of production, boosted mainly by changes in the media industry, have contributed to the overexploitation or bureaucratisation of journalism (Cohen, 2019; Miranda, 2019).

In different places in the world, the context introduced by the pandemic and, particularly, by different lockdown processes, has led to a disruption of journalists’ everyday lives, based, first and foremost, on the domiciliation of traditional workplaces (Bernadas & Ilagan, 2020; Le Cam et al., 2020; Stănescu, 2020). Because of this, the forced generalisation of teleworking among journalists must have increased the dependence on tools for long-distance communication, which contributed to the depersonalisation of the contacts with sources, to a greater use of online information (websites or social media) and to the physical absence of scenarios where real events take place. All this opened the doors to even more “sitting down” and “second-hand” journalism (Mateus, 2019).

Another clear effect of isolation concerns the decrease in chances of collectively participating and interacting in a space for debate such as the newsroom. Considering the role workplace fraternisation plays in the socialisation of norms and common concerns (Cotter, 2010), this brings a significant consequence to journalism since it entails fewer opportunities for exchange of views and peer-to-peer accountability.

A third repercussion of teleworking and new flexible labour solutions regards the potential conflict between journalists’ work and their family responsibilities, which may cause an increase in the burden of reproductive work (Power, 2020), and reinforce asymmetries and traditional gender representations (Arntz et al., 2020). In this sense, one presupposes that this phenomenon will affect particularly women and professionals with children or other dependents (Ibarra et al., 2020; International Federation of Journalists, 2020).

On the other side, the huge impact of the pandemic in everyday lives made publics more prone to absorb the most impactful things about this topic. Because it has become more difficult to keep checking information (due to new working conditions), the examples of misinformation and manipulation proliferated in the public space - either through social media and “content producers” who have little to do with journalism, or through traditional media, more pressured by the swiftness, competition and the wish to gain visibility. The damage caused to the essential trustworthy relationship between citizens and information in the public space, already going through difficult times (Fenton, 2019; Fink, 2019; Hanitzsch et al., 2017; Usher, 2018), eventually got worse. Besides fighting the pandemic, it was necessary to fight an “infodemic”4, according to the World Health Organisation (2020), or a “misinfodemic”, a concept preferred by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco, 2020) and explained in these terms: “the impacts of misinformation related to covid-19 are deadlier than misinformation on other topics, such as politics and democracy” (para. 3).

All this takes place in a context where journalists are particularly fragile, many of them with reduced worktime and pay (via lay-off), many others having been dismissed, and all of them, to a certain extent, fearful about their future (Camponez & Oliveira, 2021; Garcia et al., 2021). Precarious working conditions are a highly sensitive factor for the development of a kind of journalism that respects the highest professional standards and ethical principles, based on independence and autonomy (Waisbord, 2019), therefore, times like these added further difficulties to an area already weakened and marked by feelings of increasing professional disenchantment (Nölleke et al., 2020). This element becomes even more relevant when it is suggested that the more precarious and younger fringes of the profession are the most exposed ones to burnouts and overwork, which accentuates a sense of dissatisfaction, disappointment or cynicism concerning the activity (Christians et al., 2020; Reinardy, 2011).

The issues, doubts and challenges journalists had to face in a context of a pandemic brought about, all over the world, the fast elaboration of guiding documents and codes of conduct for their practice, under the responsibility of trade unions, professional associations, observatories, education and research entities and the media themselves5. The news coverage of the pandemic also led to a sort of “state of emergency”, given the awareness of how sensitive many of these topics were, of how rumours and lies got mixed up with the news and, therefore, how the lack of a suitable discipline of verification (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2014) could jeopardise media’s own sense of accountability. Expectations that, in this particular context, journalists showed “better care, sensitivity and greater attachment to fundamental ethical precepts”, as Aidan White says (Abidi, 2020, para. 5), were certainly high. The level of commitment of many professionals in the way they faced these challenges is a motive for some hope when it comes to regaining people’s trust in genuine information (Coddington & Lewis, 2020), although it is also clear that much of what is at stake here does not depend solely on journalists. Actually, some authors, like Örnebring (2019), believe that most of the expected changes must come from outside journalism - for instance, from school.

The fact is, to paraphrase the founder of the Ethical Journalism Network, Aidan White, coronavirus was also a topic that “brought people back to journalism”, making them understand “how reliable and rigorous information is an essential part of our lives” (Abidi, 2020, para. 3). All the indicators show how, during these months, the search for certified information (mostly on TV and online supports for traditional media) has increased to almost forgotten levels. It means that this might also be a chance to improve the media situation and their relationship with the public (Parks, 2019). And, as we are about to show you next, learning what Portuguese journalists thought and endured in these hard times, will certainly help us through this common effort.

Journalists Further Away From Newsrooms

Both the pandemic and lockdown had an impact in the different dimensions of social organisation. In this context, it seems clear that Portuguese journalists’ activity was also subjected to changes, not only in what concerns labour routines, but also in everyday issues. In this context, the answers to the survey regarding the “Study on the Effects of the State of Emergency in Journalism in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic” indicate a strong presence of the pandemic-related issues on media’s agenda. From a total of respondents that were working as journalists during the SED (799), 39.3% mentioned that topics related to covid-19 occupied about three quarters of the work they produced after the SED, and 29% admitted that the issues related to the pandemic dominated the total of the pieces they made. This perception is more evident among respondents that usually work on international or current affairs: respectively 90% and 75% of the professionals mentioned that content regarding the new coronavirus occupied more than three quarters of their production after the SED. On the other hand, when it comes to sports or culture journalists, only 48.5% and 50.9% mentioned having devoted so much space to topics related to covid-19. Out of the 21 respondents that usually address health issues, 15 referred that topics related to the pandemic represented around 75%, or more, of the content they produced after the SED.

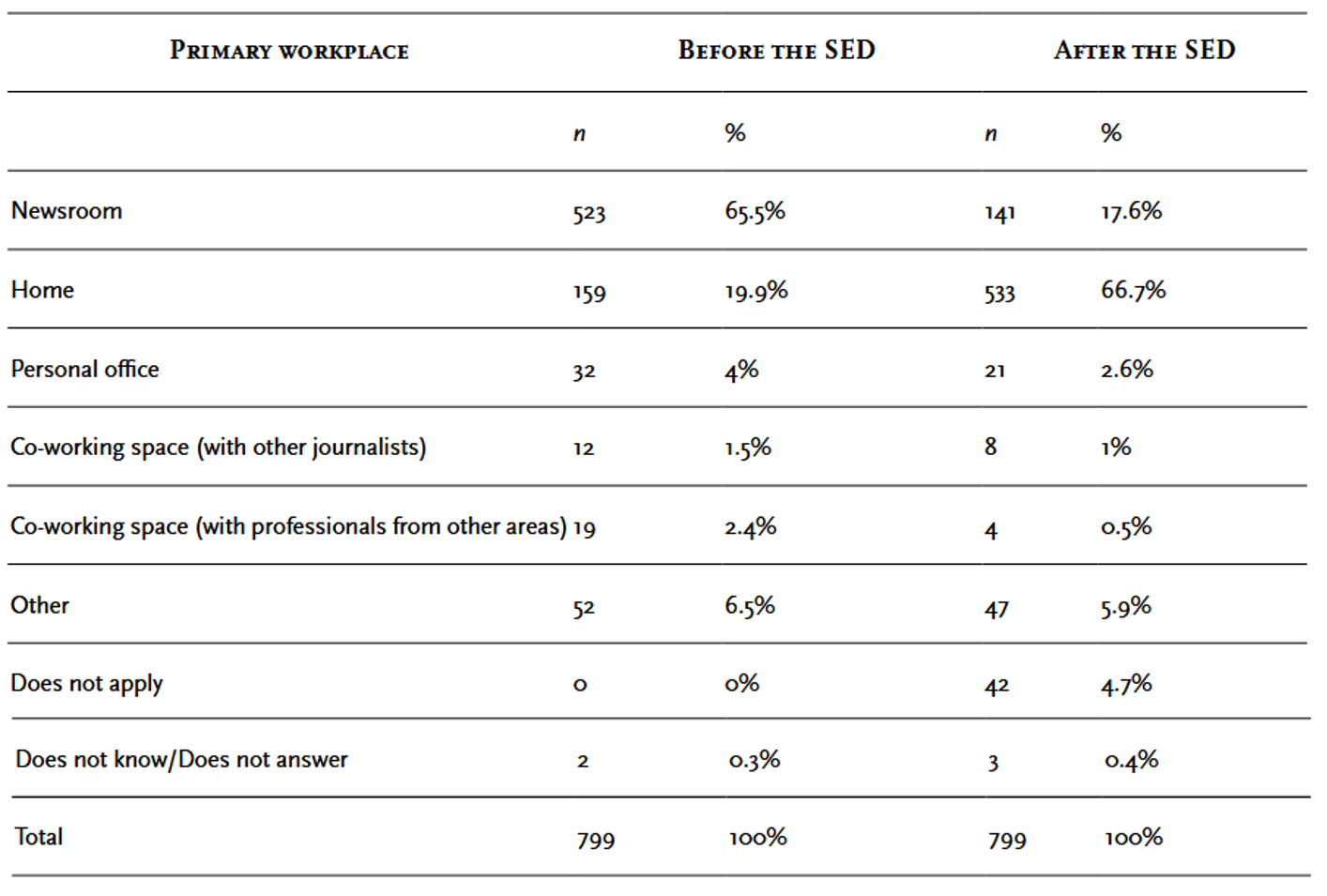

Although the newsroom seems to be, under normal circumstances, the regular work environment of most of the respondents, this paradigm is far from a standard (Table 1). As a matter of fact, of a total of respondents that were working as journalists on March 2020, 65.5% mentioned the newsroom as primary workplace before the SED, while 19.9% referred that they worked mainly from home. Unlike other employment relationships, most of the respondents that were working as collaborators or as freelancers during the SED (64.1%) mentioned that they did it from home, at the office or at co-working spaces. However, 23.4% of those worked in the newsroom. The hypothesis of atypical conditions for the inclusion of the most precarious fringes in the activity may be substantiated by a higher relative percentage of those who assume to be freelancers in formal terms, but in fact have a similar status of a typical employee, and worked in the newsroom: 47.5%.

Table 1 Primary Workplace (Before and After the SED) of Journalists Whose Main or Secondary Activity Is Journalism

Since the beginning of lockdown, there was a reconfiguration of Portuguese journalists’ labour context, dictated by the migration of the different working places to their homes. If, on the one hand, there was a decrease in the number of professionals that mentioned newsrooms, personal offices, co-working spaces or other places as primary workplaces after SED, there was, on the other hand, a substantial increase in the number of respondents that worked from home (533). The crossover between the new workplace and respondents’ types of employment relationship during the SED shows that those who used their own homes to work after the SED were mainly employees hired for an uncertain term (86%) and interns (80%). Respondents with an open-ended contract (25.4%) or with a fixed-term contract (21.4%) were the ones that showed a higher incidence of work in the newsroom. In terms of professional category, the vast majority of respondents that, during the SED, were working as interns (82.4%) worked from home; 24.8% of the editors/section coordinators, and 32.6% of the managing editors worked in the media’s facilities. In what concerns the relationship between the different types of media and the place for journalism production after the SED, teleworking was more generalised amongst respondents predominantly connected to news agencies (88%), online exclusively media (85.7%) and press (77.6%), and less preponderant amongst respondents from the radio (48%) and television (27.5%).

This reconfiguration of the labour context, due to the lockdown process, may play a part in another significant change in respondents’ professional routines, which refers to going out to cover a story. Even though the most expressive indicator concerns the variation between the number of respondents that admitted not going out to cover a story before the SED and those who mentioned not doing it after the SED (11.5% versus 33.5%), this change can also be noticed in the big decrease in the use of different means of transport, public or private (from 83.9% to 44%).

The changes in the working environment are also reflected in the gap between the number of respondents who admitted that, prior to the SED, used to contact other journalists of their media every day or almost every day (590; 66.3% of the total sample), and the number of respondents who admitted doing it after the SED (219; 24.6% of the total sample).

Close to the tendencies identified in previous studies, the average of work hours, before the SED, indicated by respondents (771) was 40 hours/week (IQR = 45-30). The average number of pieces produced every week, before the SED, referred to by respondents (697) was 10 (IQR = 20-5). The paradigm introduced by the pandemic did not bring any significant changes, being the average time spent on work indicated by the respondents (769) of 40 hours/week (IQR = 45-15), and the average of work done (703) 10 pieces/week (IQR = 25-4).

Around one third of the sample (273) admitted that, during the SED, domestic responsibilities impaired the normal exercise of the activity. Female respondents have a clearer notion of this (34.4% of the women agreed with this idea) than male journalists (28.6%). Likewise, the notion of conflict between domestic and professional burdens is more evident among respondents who reported having one or more dependents in their charge (42.8%) than among those without dependents (18.2%).

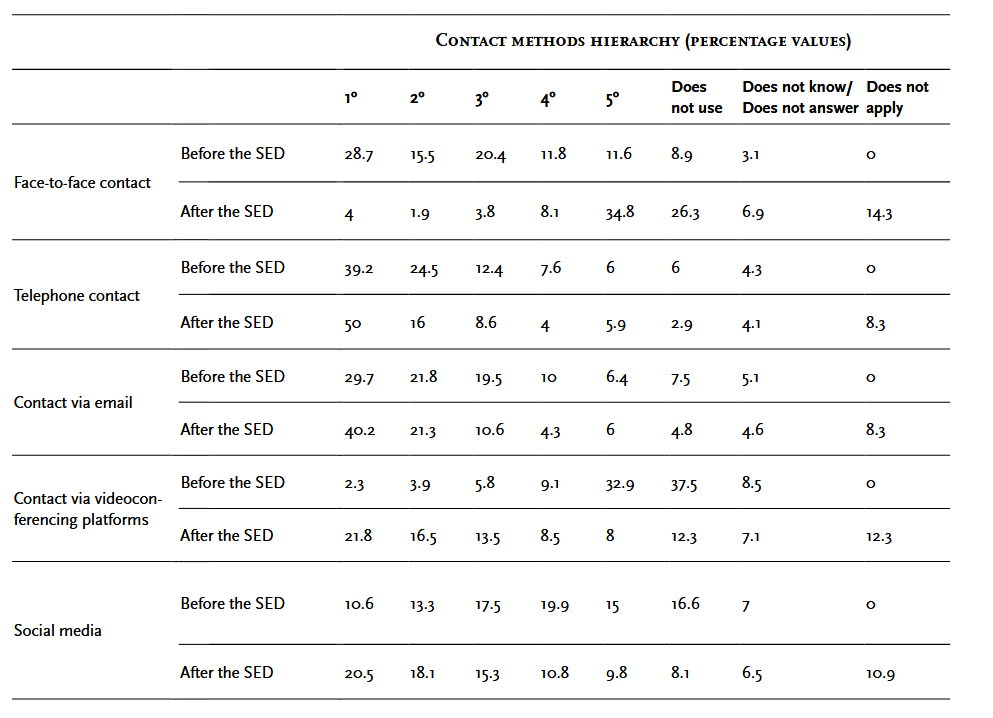

Another manifest effect of lockdown seems to be a change of practices and ways of contact with sources and with the places of events (Table 2). When respondents were asked to hierarchize the methods of contact with sources, before and after SED, a replacement of more direct and face-to-face formulae by synchronous or asynchronous distance contact models was observed. However, there was a small number of respondents (274; 34.3% of those working during the SED) who admitted having adopted new technological resources for the development of their work during lockdown. The optimism of this group of journalists about the potential effects of these new tools on the future of journalism contrasts with their opinion on the possible consequences for the ethical-professional dimension of the activity. While 67.1% of the respondents admitted a beneficial or very beneficial impact of these resources on the future of journalism, only 26.2% mentioned a similar impact on journalism’s deontological values. Their opinion is, above all, unclear as to the potential effects of these solutions on principles, with 54% of these respondents having indicated an impact neither beneficial nor harmful.

Another manifest effect of lockdown seems to be a change of practices and ways of contact with sources and with the places of events (Table 2). When respondents were asked to hierarchize the methods of contact with sources, before and after SED, a replacement of more direct and face-to-face formulae by synchronous or asynchronous distance contact models was observed. However, there was a small number of respondents (274; 34.3% of those working during the SED) who admitted having adopted new technological resources for the development of their work during lockdown. The optimism of this group of journalists about the potential effects of these new tools on the future of journalism contrasts with their opinion on the possible consequences for the ethical-professional dimension of the activity. While 67.1% of the respondents admitted a beneficial or very beneficial impact of these resources on the future of journalism, only 26.2% mentioned a similar impact on journalism’s deontological values. Their opinion is, above all, unclear as to the potential effects of these solutions on principles, with 54% of these respondents having indicated an impact neither beneficial nor harmful.

Table 2 Hierarchy of Contact Methods (Before and After the SED) of Journalists Whose Main or Secondary Activity Is Journalism

These different lines of discontinuation and change of practices and production methods cannot, of course, be disconnected from their impact on journalists’ ability to respond to the ethical-professional demands of their activity. In this domain, most respondents expressed a critical opinion about the deontological implications of the work done during the SED. In fact, when questioned about whether the context resulting from the state of emergency raised particular deontological questions to the practice of journalism, 56.7% said “yes” (505). The “no” represented 40.7% (362).

In all age groups, the percentage of positive responses exceeded 50%. Nevertheless, the perception of the phenomenon is particularly high in the group of the youngest, corresponding to about two thirds: 65.9% of those under 30; 65.2% of interns and 65% of the ones who have been on the job for a shorter period - up to 2 years. Higher-paid respondents also deviate from the average: 63.9% of the journalists whose wage is over €2,500/month, clearly a minority in the analysed universe, answered “yes” to this question, as well as 61.6% of those who earn €2,001-€2,500, and 65.1% of the ones who earn €1,000-€1,500.

If we compare the answers to this question with the different types of employment relationships, the conclusion is that respondents with “open-ended contracts” show greater sensitivity to the emergence of specific deontological issues in the context of the pandemic: 59.5% have chosen “yes”. Curiously enough, also the majority (58.7%) of freelance professionals - typical situation of precariousness - answered the same way.

The concerns with this issue are also present among respondents with a higher level of education: the “yes” is common to 65.9% of those in the group with incomplete higher education, and 65.3% of those who have completed master or doctoral degrees. On the other hand, almost half (49.4%) of the journalists who have only completed primary school, vocational or secondary education, do not see any effects of the SED in terms of ethics and deontology, when it comes to the exercise of the profession - in fact, the percentage of those who admitted that some questions had been raised in that sphere is lower (47.5%). Similarly, only four out of 10 of those holding the equivalent to a journalist’s card and 36% of the ones holding a collaborator’s card have mentioned it.

Accuracy at the Top of Ethical Concerns

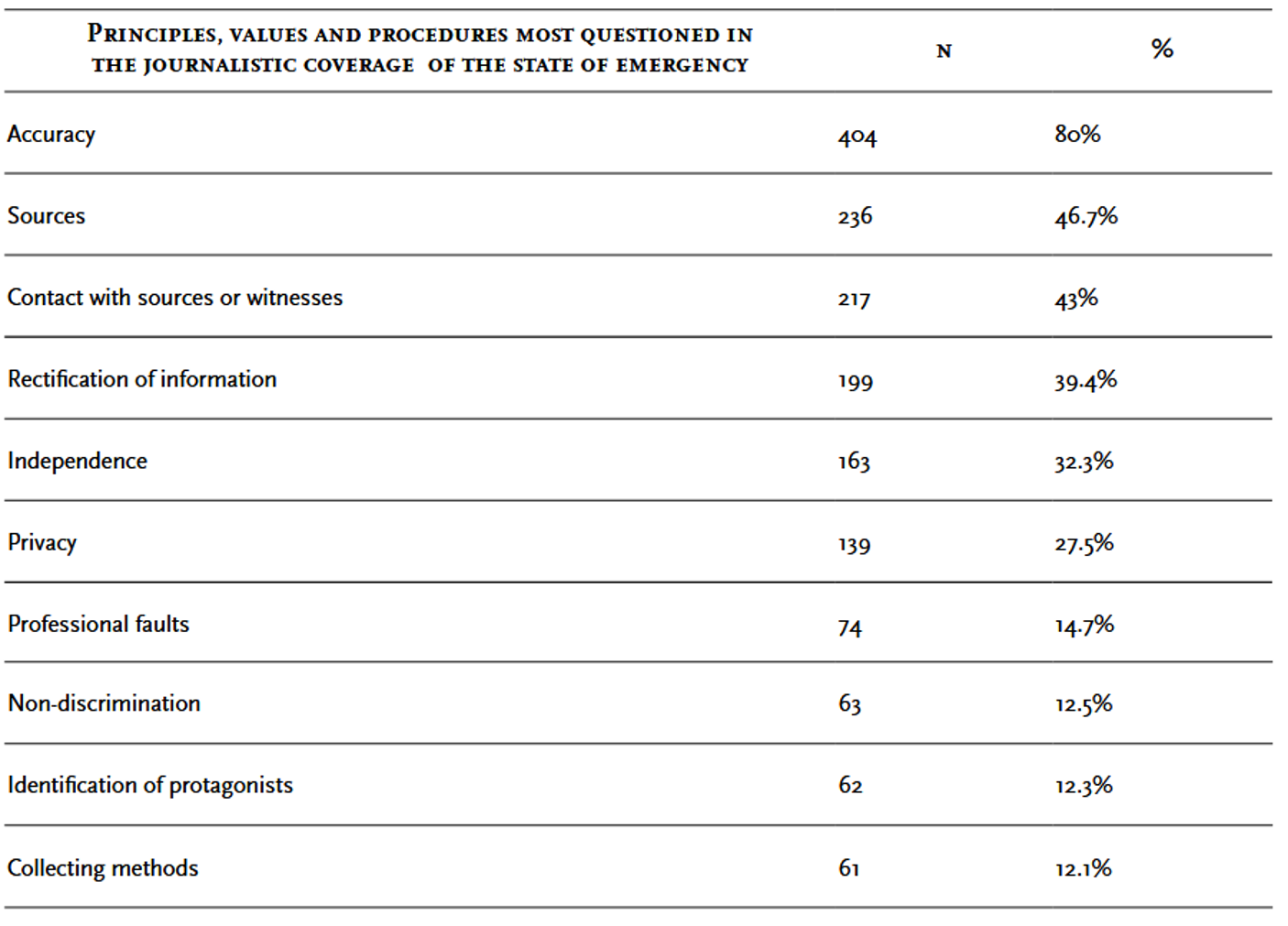

Among the principles, values and procedures most questioned in the journalistic coverage of the state of emergency (Table 3 6), “accuracy” clearly emerged as the most indicated, having gathered 80% of the respondents who considered that the SED raised deontological questions about the exercise of journalism. The reference to “accuracy” covered a number of aspects listed in the survey, namely: rejection of sensationalism; distinction between facts and opinion; repudiation of censorship; denunciation of conduct that undermines the freedom of expression; and the right to inform. Hence the particular significance of a finer reading of the results: the first mention to “accuracy” was chosen by 94.7% of the respondents over 70; by 86.2% of those under 30; by 89.1% of radio journalists, and by 88,1% of the ones that earn up to €634 a-month.

Table 3 Principles, Values and Procedures Which Were Questioned the Most During the Journalistic Coverage of the State of Emergency, For the 505 Journalists Who Considered That the SED Raised Deontological Questions to the Exercise of Journalism

With a much less expressive global percentage (46.7%), the following topic was “sources of information” which took a prominent place among respondents who have journalism as their main activity (47.2%). This referred to issues such as the fight against restrictions on access to information; the hearing of parties with compelling interests; source identification as a rule; the allocation of opinions and respect for professional secrecy. In this group of professionals, less than one out of 10 (9.8%) indicated “information collection methods”. This aspect, overall the less mentioned one (only 12.1%), included the inhibition of the use of illegal or unauthorised means, except for special case, as well as the duty not to hide the professional identification or the staging of situations in order to take advantage of people’s good faith.

Based on the answers obtained, there is a particularity concerning news agencies’ journalists. In the survey, they are the only ones for whom “accuracy” does not stand out when compared to other deontological values. In this category, “accuracy” and “sources of information” were pointed out in equal percentages (70.4%) as sensitive topics concerning journalistic coverage during the SED.

Also noteworthy is the fact that half of the journalists whose activity is carried out exclusively on online platforms have indicated “contact with sources and witnesses” as the second ethical-deontological aspect that has been questioned the most in the coverage of events. This component, mentioned by 43% of the respondents, referred to the issues raised by the contact with citizens: avoid causing humiliation, interfering with pain or exploiting the psychological, emotional or physical vulnerability and ensuring serenity, freedom and responsibility of sources or witnesses.

The issue of “privacy” - associated to the respect for that right, except in the case of contradiction between the individuals’ conduct and the values and principles they advocate publicly; to the assessment of the nature of the case and condition of the person; or to the preservation of the right to intimacy and justification for exceptions in case of public interest - was mentioned by just over a quarter of the respondents (27.5%). It is evident that a higher level of education corresponds to greater attention to the issue of privacy in the journalistic practice. Actually, when it comes to the group of people that got, at most, to secondary school, only 21.3% mentioned it as one of the most questioned values in the coverage of the state of emergency, while among people with a master’s, doctorate and post-graduate degrees, percentages rose to 29.8% and 32.8%, respectively.

The eventual increase in production, by journalists, of the so-called “sponsored content” was the subject of a question in the survey, which specified that it only concerned situations of content paid by external entities rather than by the company to which the professional was linked. The overwhelming majority (90.4%) of respondents that were working at the time of the SED denied having been asked by their editors, during the state of emergency, to carry out such work, hybrid products that have been developed by the media as a way of counterbalancing the decrease in revenue coming from traditional advertising.

On the other hand, 5.3% admitted that such requests were made by their superiors and only 2.4% acknowledged that it happened without them previously being informed about it. By adding up the two, it is determined that 7.7% of the respondents (61) confirmed they had already been asked to produce “sponsored content”. Young people presented themselves as especially affected. In fact, more than one third (exactly 35.5%) of those who had been working for less than 5 years, about one fifth (20.5%) of those in internship and 17.2% of the ones under 30 chose one of these answers - in any case, way above the average.

An analysis of the answers according to monthly pay grades leads to similar conclusions: the ones who claimed to have received requests for “sponsored content” were the journalists that earned between €635 and €900/month (10.9%, to which we can add 3% of those who have received requests without prior information). On the opposite side, among all the journalists with monthly pay grades above €1,500, this kind of request occurred in much lower percentages - between 1.1% and 2.8%.

One last question aimed to determine whether the request for the production of “sponsored content”, was something new or had already happened prior to the SED. From the 42 respondents that mentioned having been asked to do it, 37 (88.1% of the total) revealed that it had happened previously, which shows that the initiative was not a direct consequence of the state of emergency declared in the country.

Conclusion

The results of this survey, rather than revealing new problems, indicate that the issues deriving from the pandemic and lockdown tended to accentuate pre-existing challenges and dilemmas.

As far as professional routines are concerned, the data suggest that, despite technological innovation and the emergence of new dynamics of information production (Deuze & Witschge, 2020), the newsroom is still journalists’ regular work environment. If, on the one hand, the group of respondents working outside the newsroom may result from more specific professional profiles (such as correspondents, collaborators or sports/parliamentary journalists), on the other hand, the amount of service providers who have the newsroom as their primary workplace presupposes specific circumstances, like “fake freelance” (Bibby, 2014) - that is, professionals with formal bonds of a freelancer, but who take on permanent positions, with defined assignments and schedules.

One of the most significant effects of lockdown in Portuguese journalists’ routines translates into a relatively comprehensive tendency of domiciliation of their activity, which is assumed as a matrix factor for other changes in the daily lives of professionals - symptomizing lines of isolation, a sedentary lifestyle and the bureaucratisation of journalists and of their work.

The replacement of more face-to-face ways of interaction with sources and events by remote ways of contact (also reflected in the results of this study) is not a new or ephemeral phenomenon. Rather, it is suggested that it is a response to trends of labour reorganisation, underlying the technological and economical reorganisation of the media industry. Bearing in mind what they represent in terms of observance of professional practices related to the confrontation and validation of information, it is, nonetheless, important to stress the boundary between more synchronous and direct ways of contact (such as telephone or videoconferencing platforms), and less interactive and simultaneous means of communication (like the email or social media). This distinction is even more relevant when the impact of lockdown in the respondents’ routines left not only marks of depersonalisation in the ways of interacting with sources, but also an increasing use of asynchronous contact formulae, heightening potential scenarios of “taylorisation” of journalism, “sitting down journalism” and recycling of information transmitted online.

Considering the comparison between averages regarding the number of hours devoted to the professional activity and the amount of content produced, before and after SED, it is possible to conclude that these domiciliation processes did not translate, generally speaking, into a change of volume and rhythm of journalistic production. However, one should not infer that lockdown did not affect the intensity of the work carried out by Portuguese journalists, given that one third of the sample reported that, at the time of the SED, domestic responsibilities interfered with the normal exercise of the profession. Even if the reasons for a higher evidence of this perception among the respondents with dependents may be self-explanatory, the fact of being more common among female respondents is likely to require further reflection, since it may eventually reveal a conflict between the perpetuation of traditional gender and activity roles.

In addition to the changes in the production routines of the respondents, lockdown has also entailed their social isolation, which will tend to result in their distancing or alienation from the professional community. In this context, the oscillation identified between the habit of contacting other journalists, before and after the SED, is significant, as it represents a decrease in opportunities for professional participation, for sharing common concerns or, even, for peer accountability.

When it comes to ethics, the conclusion is that more than half of the respondents agree that the context resulting from the state of emergency has brought particular deontological questions to the exercise of journalism. Nevertheless, there are slight differences between the different subgroups, with the young journalists expressing greater concerns regarding the negative effects experienced in journalism, in this period of time. In fact, the percentage of those who have referred to the emergence of specific deontological issues is over 65%, whether one takes into account the age of the respondents, the ones with the shortest time on the job or their status as trainees. On the other hand, those equated to journalists and collaborators are among the ones that least claimed to have identified new problems in this field. This is obviously connected to the fact that, in both cases, these are people whose contact - one might say, daily - with the profession is less frequent.

Regarding the attempt to better define the ethical-deontological challenges raised, one should emphasise the concern with “accuracy” of information - by far the most mentioned among the 10 proposed items in the survey, and, in a very transversal way, to all professional categories, age groups or levels of remuneration. This particular focus on accuracy cannot be unrelated to the countless examples of misinformation and manipulation seen in the news coverage of the pandemic, with well-known negative effects.

Concerning the quite current theme of “sponsored content”, which is halfway between journalism and advertising, we may conclude that it does not seem to have had a particular incidence in this period, in spite of the strong decrease in media revenues. Even so, the survey data converge in the same direction: in general terms, it is again the youngest journalists, with less time in the profession, with lower salaries and more fragile job titles who tend to be asked to produce this sort of content.

In short, the work of Portuguese journalists has been affected in this period by a number of constraints, not all new, but certainly more pressing, that ask for the urgency of collective debate and the search for solutions that improve labour conditions, as well as the ability to better address the ethical requirements of the profession.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020.

REFERENCES

Abidi, A. (2020, 22 de abril). Journalism ethics expert on coronavirus crisis: “This is a human story above all”. European Journalism Observatory. https://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/journalism-ethics-expert-on-coronavirus-crisis-this-is-a-human-story-above-all [ Links ]

Arntz, M., Yahmed, S. B., & Berlingieri, F. (2020). Working from home and covid-19: The chances and risks for gender gaps. ZEW. https://www.zew.de/fileadmin/FTP/ZEWKurzexpertisen/EN/ZEW_Shortreport2009.pdf [ Links ]

Berkowitz, D. (2019). A sociological perspective on the reporter-source relationship. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen, & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp. 165-179). Routledge. [ Links ]

Bernadas, J. M. A. C., & Ilagan, K. (2020). Journalism, public health, and covid-19: Some preliminary insights from the Philippines. Media International Australia, 177(1), 132-138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20953854 [ Links ]

Bibby, A. (2014). Employment relationships in the media industry (Working paper No. 295). International Labour Organization. http://www.andrewbibby.com/pdf/wcms_249912.pdf [ Links ]

Brennen, J. S., Simon, F., Howard, P. N., & Nielsen, R. K. (2020, 7 de abril). Types, sources, and claims of covid-19 misinformation. Reuters Institute. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation [ Links ]

Camponez, C. (2011). Deontologia do jornalismo. Almedina. [ Links ]

Camponez, C., & Christofoletti, R. (2019). Reinventando pactos globais para a ética da comunicação e do jornalismo. Mediapolis, 9, 5-12. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-6019_9_0 [ Links ]

Camponez, C., & Oliveira, M. (2021). Jornalismo em contexto de crise sanitária: Representações da profissão e expectativas dos jornalistas. Comunicação e Sociedade, 39, 251-267. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).3178 [ Links ]

Cardoso, G., Baldi, V., Quintanilha, T. L., Paisana, M., & Pais, P. C. (2020). Impacto do branding e conteúdos patrocinados no jornalismo. OberCom. https://obercom.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Sponsored_content_FINAL_edit_Spain_UK.pdf [ Links ]

Carlson, M. (2016). Metajournalistic discourse and the meanings of journalism: Definitional control, boundary work, and legitimation. Communication Theory, 26(4), 349-368. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12088 [ Links ]

Carlson, M., & Lewis, S. (Eds.). (2015). Boundaries of journalism - Professionalism, practices and participation. Routledge. [ Links ]

Chowdhury, M. A. (2020, 10 de março). Tips for journalists covering covid-19. Global Investigative Journalism Network. https://gijn.org/2020/03/10/tips-for-journalists-covering-covid-19/ [ Links ]

Christians, C. G., Fackler, M., Richardson, K. B., Kreshel, P. J., & Woods, R. H., Jr. (2020). Media ethics: Cases and moral reasoning. Routledge. [ Links ]

Christofoletti, R. (2014). Preocupações éticas no jornalismo feito por não-jornalistas. Comunicação e Sociedade, 25, 267-277. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.25(2014).1873 [ Links ]

Coddington, M., & Lewis, S. (2020, 7 de outubro). What work is required to build public trust in news? RQ1. https://rq1.substack.com/p/the-emergence-of-a-new-kind-of-journalistic [ Links ]

Cohen, N. S. (2019). At work in the digital newsroom. Digital Journalism, 7(5), 571-591. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1419821 [ Links ]

Cotter, C. (2010). News talk: Investigating the language of journalism. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dart Center. (2020, 28 de fevereiro). Covering coronavirus: Resources for journalists. Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma. https://dartcenter.org/resources/covering-coronavirus-resources-journalists [ Links ]

Deuze, M. (2010). Managing media work. Sage. [ Links ]

Deuze, M., & Witschge, T. (2020). Beyond journalism. Cambridge Polity Press. [ Links ]

Donsbach, W. (2010). Journalists and their professional identities. In S. Allan (Ed.), The Routledge companion to news and journalism (pp. 38-48). Routledge. [ Links ]

Fenton, N. (2010). News in the digital age. In S. Allan (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to news and journalism (pp. 557-567). Routledge. [ Links ]

Fenton, N. (2019). Dis(trust). Journalism, 20(1), 36-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918807068 [ Links ]

Fidalgo, J. (2009). O lugar da ética e da auto-regulação na identidade profissional dos jornalistas. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian; Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. [ Links ]

Fidalgo, J. (2016). Disputas nas fronteiras do jornalismo. In T. Gonçalves (Ed.), Digital media Portugal - ERC 2015 (pp. 35-48). ERC - Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social. https://www.erc.pt/pt/estudos-e-publicacoes/novos-media/estudo-digital-media-portugal-2015 [ Links ]

Fink, K. (2019). The biggest challenge facing journalism: A lack of trust. Journalism, 20(1) 40-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918807069 [ Links ]

Friend, S., & Singer, J. (2007). Online journalism ethics - Traditions and transitions. M. E. Sharpe. [ Links ]

Garcia. J. L., Matos, J. N., & Silva, P. A. (2021). Jornalismo em estado de emergência: Uma análise dos efeitos da pandemia covid-19 nas relações de emprego dos jornalistas. Comunicação e Sociedade, 39, 269-285. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.39(2021).3177 [ Links ]

Hanitzsch, T., Van Dalen, A., & Steindl, N. (2017). Caught in the nexus: A comparative and longitudinal analysis of public trust in the press. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740695 [ Links ]

Ibarra, H., Gillard, J., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2020, 16 de julho). Why WFH isn’t necessarily good for women. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/07/why-wfh-isnt-necessarily-good-for-women [ Links ]

Ikonen, P., Luoma-aho, V., & Bowen, S. A. (2017). Transparency for sponsored content: Analysing codes of ethics in public relations, marketing, advertising and journalism. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 11(2), 165-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1252917 [ Links ]

International Federation of Journalists. (2020, 23 de julho). Covid-19 has increased gender inequalities in the media, IFJ survey finds [Press release]. https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/category/press-releases/article/covid-19-has-increased-gender-inequalities-in-the-media-ifj-survey-finds.html [ Links ]

Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2014). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect. Random House. [ Links ]

Le Cam, F., Libert, M., & Domingo, D. (2020, junho). Journalisme en confinement. Enquête sur les conditions d’emploi et de travail des journalistes belges francophones. Les Carnets du LaPIJ, 1. https://www.ifj.org/actions/ifj-campaigns/decent-work-day-2020-telework.html?tx_wbresources_list%5Bresource%5D=565&cHash=1c76658a1ac01146cfeaa9e1c4b30e2a [ Links ]

Lewis, S., & Westlund, O. (2016). Mapping the human-machine divide in journalism. In T. Witschge, C. Anderson, D. Domingo, & A. Hermida (Eds.), The Sage handbook of digital journalism (pp. 341-353). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957909.n23 [ Links ]

Martins, P. (2019). O rigor como eixo central da atividade jornalística. Mediapolis, 9, 41-55. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-6019_9_3 [ Links ]

Mateus, S. (2019). New media, new deontology - Ethical constraints of online journalism. Mediapolis 9, 13-26. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1034-6449 [ Links ]

Mathisen, B. (2019). Ethical boundaries among freelance journalists. Journalism Practice, 13(6), 639-656. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1548301 [ Links ]

McBride, K., & Rosenstiel, T. (Eds.). (2014). The new ethics of journalism - Principles for the 21st century. Sage. [ Links ]

Meyers, C. (Ed.). (2010). Journalism ethics - A philosophical approach. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Miranda, J. (2019). O papel dos jornalistas na regulação da informação: Caraterização socioprofissional, accountability e modelos de regulação em Portugal e na Europa [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade de Coimbra]. Estudo Geral. https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/handle/10316/87571 [ Links ]

Nölleke, D., Maares, P., & Hanusch, F. (2020). Illusio and disillusionment: Expectations met or disappointed among young journalists. Journalism, 1-17. Publicação eletrónica antecipada. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920956820 [ Links ]

objETHOS. (2020). Guia de cobertura ética da covid-19. https://objethos.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/guia_covid_objethos.pdf [ Links ]

Örnebring, H. (2019). Journalism cannot solve journalism’s problems. Journalism, 20(1), 226-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918808690 [ Links ]

Pacheco, L., & Freitas, H. S. (2014). Poucas expectativas, algumas desistências e muitas incertezas. In J. Rebelo (Ed.), As novas gerações de jornalistas portugueses (pp. 21-36). Editora Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

Parks, P. (2019). Toward a humanistic turn for a more ethical journalism. Journalism, 21(9), 1229-1245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919894778 [ Links ]

Pickard, V. (2019). The violence of the market. Journalism, 20(1), 154-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918808955 [ Links ]

Plaisance, P. (2009). Media ethics - Key principles for responsible practice. Sage. [ Links ]

Power, K. (2020). The covid-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 67-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561 [ Links ]

Reinardy, S. (2011). Newspaper journalism in crisis: Burnout on the rise, eroding young journalists’ career commitment. Journalism, 12(1), 33-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910385188 [ Links ]

Riordan, K. (2014). Accuracy, independence, and impartiality: How legacy media and digital natives approach standards in the digital age. Reuters Institute Fellow’s Paper. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/accuracy-independence-and-impartiality-how-legacy-media-and-digital-natives-approach [ Links ]

Ryfe, D. (2019). The ontology of journalism. Journalism 2019, 20(1), 206-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756087918809246 [ Links ]

Siapera, E., & Veglis, A. (2012). Introduction: The evolution of online journalism. In E. Siapera & A. Veglis (Eds.), The handbook of global online journalism (pp. 1-17). John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Singer, J. (2014). Sem medo do futuro: Ética do jornalismo, inovação e um apelo à flexibilidade. Comunicação e Sociedade, 25, 49-66. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.25(2014).1858 [ Links ]

Stănescu, G. (2020). The importance and role of the journalist during covid-19. Lessons learned from home journalism. In D. V. Voinea, & A. Strungă (Eds.), Research terminals in the Social Sciences (pp. 105-114). SITECH Publishing House. [ Links ]

Tong, J. (2017). Introduction: Digital technology and journalism - An international comparative perspective. In J. Tong, & S. H. Lo (Eds.), Digital technology and journalism (pp. 1-21). Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Unesco. (2020).Combate à desinfodemia: Trabalhar pela verdade em tempos de covid-19 .https://pt.unesco.org/covid19/disinfodemic [ Links ]

Usher, N. (2018). Re-thinking trust in the news - A material approach through ‘objects of journalism’. Journalism Studies, 19(4), 564-578. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1375391 [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. (2019). The vulnerabilities of journalism. Journalism, 20(1), 210-213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918809283 [ Links ]

Ward, S. (Ed.). (2013). Global media ethics: Problems and perspectives. Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Ward, S. (2016). Digital journalism. In B. Franklin, & S. Eldridge (Eds.), The Routledge companion to digital journalism studies. Routledge. https:// doi.org/10.4324/9781315713793-4 [ Links ]

Ward, S. (2018). Reconstructing journalism ethics: Disrupt, invent, collaborate. Media & Jornalismo, 18(32), 9-17. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_32_1 [ Links ]

White, A. (2014, 30 de setembro). Why ethical journalism needs a magna carta for the web. Ethical Journalism Network. https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/why-ethical-journalism-needs-a-magna-carta-for-the-web [ Links ]

Wilkins, L., & Christians, C. (Eds.). (2009). The handbook of mass media ethics. Routledge. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation. (2020, 25 de agosto). Immunizing the public against misinformation. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/immunizing-the-public-against-misinformation [ Links ]

Zelizer, B. (2019). Why journalism is about more than digital technology. Digital Journalism, 7(3), 343-350. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1571932 [ Links ]

Received: January 26, 2021; Accepted: May 21, 2021

texto em

texto em