1. Introduction

The possibility of affirming the cultural heritage condition of subtitled audiovisual work in the contemporary European context should be estimated in light of the very concept of “intercultural competence” (Santiago Vigata, 2010, p. 3), both in its tangible and operational aspects:

tangible, as it is a principal competence that the individual acquires during their language and cultural learning.

operational, to the extent that it trains that individual to establish relationships with foreign cultures.

Following the above, it can be affirmed that, in the audiovisual field, preference for the original version (OV) of a media product, or, in its absence, for an original version with subtitles (OVS), per se constitutes a militant, propitiatory expression of intercultural communication.

The cultural potential of film subtitling lies both in its facilitating role for immersing spectators in foreign languages (Toury, 1995, p. 59) and in its function as an indicator of the vehicular nature of a language in a particular culture and its potential to include collectives with sensory disabilities, in light of the innovative contributions of Romero-Fresco (2018, pp. 199-224).

The cultural potential of subtitling goes beyond the realm of cinema to venture into other forms of electronic entertainment, such as video games. Accordingly, Jan Pedersen (2015, pp. 157-158) echoes the academic disdain that often surrounds the study of videogame translation, even though the overall gross income of the gaming industry exceeds those of the film or musical industries, constantly increasing its penetration in “first world” households. Méndez-González (2015, pp. 76-81) adds an interesting aspect to this reflection, because if the traditional audiovisual market - bowing down to dubbing dynamics and impervious to the use of subtitling - is, in turn, the source of the design and development of many productions based on graphic computing, the future of OV and OVS is not looking good.

Based on a critical analysis of community cultural policies and some representative case studies, we aim at proving the close link between the normalisation processes of minority languages in Europe and the use of audiovisual subtitling - the guarantor of the preservation of the originality of the work and its value as European cultural heritage - and the need to propose a European protocol transcending the context in pursuit of the structure. Thus, we will focus on our key challenges and recommendations to provide Europe with a protocol for subtitling films in the digital age through three case studies: the Galician, Basque and Catalan audiovisual cases.

2. Theoretical Framework

The concept of “normalisation” demonstrates its complexity by involving political, sociocultural, historical, economic, geographical variables. Those are evident in a wide range of contributions. Among the most noteworthy are Lasagabaster (2017), Cormack and Hourigan (2007) and Seosamh Ó Murchú (1991). “Children learn a whole new ‘language’ from television which they bring with them into formal learning situations which they use among themselves to express feelings and emotions which comply with what are often set piece experiences portrayed on television” (Ó Murchú, 1991, pp. 89-90).

Also, the prolific Irish field of intercultural studies Eithne O’Connell (2003) later enriched the debate with her forward-looking reflections on audiovisual translation and its core character in the normalisation of non-dominant minoritised languages, especially in the age range of children and adolescents strongly determined by the omnipresence of electronic devices that promote continuous exposure to audiovisual content: “the production and translation of written and/or audiovisual material for children are central to the development of the younger generation’s language skills and is, therefore, of crucial importance to the survival of the minority language into the future” (O’Connell, 2003, p. 61).

Regarding the overlapping of subtitling in the dominant business model, the choice of the vehicular language appears as a sign of cultural identity and as a determining element of the very process of commercial film use (by conditioning subsequent choices of original viewing, subtitling or dubbing), without undermining the duty of cultural industries in terms of preserving the integrity and language originality of the film in a “sustainable exploitation environment” (Kääpa, 2018, p. 226).

It is undeniable that the income from cinema screenings in theatres is less and less relevant in the total income of film production. However, the success of a film in the cinemas continues to be an important advertising claim for its subsequent dissemination on a dense network of platforms and digital media (García Santamaría, 2015, p. 61). Moreover, on the other hand, traditional cinema continues to preserve that “liturgy” of diegetic appropriation of a story by the cinematographic spectator: a personal appropriation in which the choice of vehicular language is decisive.

It is time to refute one of the topics that tend to be used against audiovisual subtitling: its impossible relationship with diegesis. The ardent naysayers of cinema subtitling - who consider the superposition of alphanumeric characters on images to be a disturbance in the process of immersion of the spectator in the film diegesis - do not usually attribute the same to dubbing, despite its incontestable artificiality and supplanting of performance acting. On the contrary, Méndez-González (2015, p. 88) ponders the intercultural effectiveness of subtitling as a crucial part of “targeting” - according to the term’s linguistic meaning - and the location of the audiovisual work, already in its launching in foreign markets or to encourage the accessibility of people with hearing disabilities.

The normalisation of the practice of subtitling preserves the language integrity of the film without interfering in its diegesis while guaranteeing equal access to culture, regardless of the particularities - not sensory barriers - of each person: a guarantee that it will surpass the boundaries of film to enter other environments of audiovisual consumption that, like videogames, prioritise the quality of gaming - interactivity, immersion, and so on - beyond diegesis: “having subtitles in games should not be one of those things which are added in ‘because everyone else is doing so’ or at the ‘last minute’ but instead as something which can enhance the player experience” (Griffiths, 2009, p. 4).

In any case, only in light of that symbolic consideration and the non-transferable cultural experience attributed to cinemas can European protectionism be understood through provisions such as the controversial screen quota:

as a reaction to this shift of power and fearing both the economic and cultural impact of Hollywood, many European governments introduced measures to protect their domestic film industries, mostly in the form of import and screen quotas. These measures found expression in the “Special Provisions Relating to Cinematograph Films”, which became part of GATT [General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade] 1947. (Burri, 2014, p. 480)

Pay attention to the information that, relative to 2016, is provided jointly by the European Audiovisual Observatory and the European Film Agency Research Network. According to them, although the screen share in EU countries fell slightly (from 27 % to 26.7%), the share of films produced in Europe with investments from the United States of America - an unconventional pairing that challenges the credibility of the very conception of “European cinema” - suffered a significant shrinkage (from 7.1% to 3.6%) in a context in which European box office collections remained stable (European Audiovisual Observatory, 2017). Through the analysis of the percentages applied in European cinematography, it is possible to identify the mismatch between the screen quota and the subtitle quota, thus violating the distinctive identity of the film: its choice of the original language.

On the other hand, Law No 55/2007, of December 28, on Cinema - the transposition of European legislation into the Spanish legislative framework - stipulates:

to fulfil the screen quota, the sessions in which they are screened will have double value in the calculation of the percentage foreseen in the previous section: a) EU fiction films in original version with subtitles to one of the official Spanish languages. (Ley 55/2007, 2007, Art. 18.2.)

Despite its protectionist nature, since the end of the 20th century, European legislation has shown its inability to tackle the exponential shrinkage of the classical screening model: as an example in this regard, García Santamaría (2015, p. 171) warns of how the cinema sector in Spain has collapsed, dropping from 7.761 screens in 1968 to hitting rock bottom in 1994 with only 1.773 screens.

While cinemas have experienced an increase throughout Europe, driven by the emergence of multiplex cinemas, mostly urban-based, the crisis in the sector finished off 86% of the screens located in towns of less than 10.000 inhabitants, while cities with more than 100.000 inhabitants had lost 20% of their cinemas (García Santamaría, 2015, pp. 177-178). Such a drastic shrinkage of cinemas brought an increase in the cost of tickets that came to exacerbate, in turn, the trending loss of cinemagoers.

Everything referred to up to this point should be placed, as García Santamaría (2015, pp. 351-352) reminds us, in an unprecedented context in which the experience of film consumption has been blatantly emancipated from the cinema. It is conceived exclusively for screening films towards multi-purpose spaces that - in the wake of digitalisation - diversify their sources of income by hosting activities as varied as online video games, broadcasting sports and cultural events (live or deferred), private screenings, social celebrations, and so on.

It is a new audiovisual landscape dominated by over-the-top (OTT). In fact, the emergence of OTT (such as Netflix, HBO, or Disney +) generated multiple hopes regarding the presence of non-hegemonic languages in their available catalogues. Unfortunately, far from the expected diversity of content, themes, consumer profiles, and so on, a homogenising (in)culture was imposed that entirely affects non-hegemonic languages.

A good example of this was the landing of Disney + in Spain on March 24, 2020, accompanied by the controversy and conflict with the Generalitat de Catalunya over eliminating content in the Catalonian language from its catalogue. A year later, Lilja Dögg Alfreðsdóttir (Iceland’s minister of education, science, and culture) has secured an explicit commitment from Bob Chapek (chief executive officer of The Walt Disney Company) to include Icelandic language content in the company’s catalogue.

Despite the “small” concessions to minority languages, the report of the European Audiovisual Observatory (Jiménez-Pumares, 2020) confirmed the overwhelming dominance of U.S. platforms in the European subscription streaming market, and therefore of the English language: a market valued at €9,700,000,000 ($11,710,000,000 ) in 2020.

3. Methodology

Regarding the methodological approach of our article, our starting point is an intensive documentary analysis methodology, involving a critical and exhaustive review of essays, legislation, and reports, as a result of applying controlled hermeneutics through inference - in the manner of Bardin (2013) and Krippendorf (2013).

However, the essay literature review results were confronted with a series of in-depth interviews with some 30 European experts (who will endorse the validity of the proposed topics or propose new ones). They were summoned to two international events, held in 2019 and 2020: international forum “Languages and Cinema. Indicators for a European Subtitling Programme” and “Languages and Cinema II. For a European Subtitling Programme in Non-Hegemonic languages”.

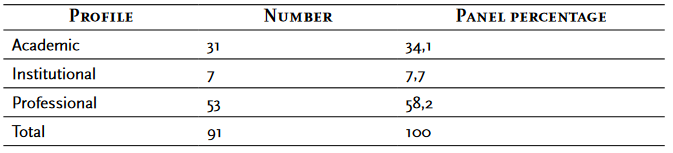

Delphi method was chosen for the collection and tabulation of the information, through two waves of questionnaires, which considered the following expert panel, made up of 91 specialists, with an average age of 49.09 years, of which 65.9% were men and 81.3% belonged to the Spanish State and the rest were European experts. All of them are experts in European audiovisuals in general, and in subtitling policies in particular, according to the profiles shown in Table 1.

Regarding the justification of the chosen sociogeographic sample, it is evident that the Galician, Basque and Catalonian cases have a particular interest:

They are three geographic areas whose languages are not shared by the rest of the state to which they belong and whose non-hegemonic languages share co-officiality with a hegemonic language.

At the same time, these are autonomous communities that, due to their condition, must combine three different political-administrative regimes: the European, Spanish and autonomous community regulations in question, whose practical application is usually not harmonious.

Furthermore, our starting hypothesis emerges precisely in this sense: would it be possible to extrapolate the three cases analysed, located in the Iberian Peninsula, to the complexity of the European audiovisual reality? Indeed, the three cases analysed share a transcendental problem concerning heritage and commercial aspects in the EU audiovisual policy: a redefinition of the film’s nationality.

4. Analysis of Three Case Studies

We will focus on the Galician and Catalan film industries - under the protection of the demolinguistic analysis proposed by the philologists of the Real Academia Galega (http://www.realacademiagalega.org/) Xaquín Loredo and Henrique Monteagudo (2017) - introducing the Basque film industry as a middle ground between both models. Thus, applying the Catalan language intergenerational transmission rate (ITIC, índice de transmisión intergeneracional del catalán in Spanish: ) - created by Torres (2009) - to the Galician and Catalan demolinguistic developments in the first decade of the 21st century, Loredo and Monteagudo (2017, p. 113) note similar, although contrary, absolute values in their ITIC: in keeping with the contributions of O’Rourke and Ramallo (2015), both philologists note language revitalisation attitudes in the Catalan population that in Galicia are lacking a significant weight in absolute terms.

Now, while taking the briefest glimpse at the film industries of two examples of European minoritised film sectors, Galician and Catalan, we can easily isolate the two main obstacles faced by the normalising potential of audiovisual subtitling:

there is a notorious disparity between the bombastic European Union declarations and their implementation, by state and local administrations, in erratic, random and contingent packages of measures that reveal a systemic absence of results;

a foreign market impervious to those contents not subjected to the use of dominant languages for their production and diffusion, and an internal market whose reduced demand fuels the hackneyed sales pitch of the low profitability of the product.

According to Herreras (2010, p. 11), the radio and television projects of a global nature that emerged throughout Europe during the second half of the 20th century provided an incentive to normalise the use of non-dominant European languages; however, this aspect needs to carry on improving. That is the case of Galicia, a “Stateless Nation” -according to Schlesinger’s (2000, pp. 19-20) definition - located in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, with a population of more than 2,700,000 inhabitants, with its own language, government and parliament, as well as its own public broadcasting service, the Corporación de Radio y Televisión de Galicia (CRTVG), supposedly a bulwark of an idiosyncratic audiovisual industry.

The CRTVG prioritises audiovisual dubbing of foreign languages and scarcely broadcasts subtitled programming, except for a weekly film in the Butaca Especial programme, relegated to the early slot on Saturday mornings. Already in 2012, the Group of Audiovisual Studies of the University of Santiago de Compostela had warned (Ledo-Andión & Castelló-Mayo, 2012, p. 113) of the need to enable a space on the CRTVG website (http://www.crtvg.es/) addressed to the Portuguese-speaking community, in order to open new lines of business and cultural integration, in which subtitling would have to become an essential tool.

In fact, that innovative proposal was echoed retrospectively - among others - in the “Protocol to Ensure Language Rights” (Hizkuntza Eskubideak Bermatzeko Protokoloa/Protocol to Ensure Language Rights, 2016), developed under the guidance of the Kontseilua (The Council of Basque Language Entities) and the Fundación Donostia del País Vasco, as well as by numerous language communities, among them Galicia. Measures have been developed - specifically in section 6 on media and new technologies - to accompany articles 35 to 40 of the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights, most notably, the promotion of minoritised languages in the publicly-owned media, advising, in the case of television, the use of subtitles or a second audio channel (Hizkuntza Eskubideak Bermatzeko Protokoloa/Protocol to Ensure Language Rights, 2016, p. 27): recommendations disregarded by the CRTVG, despite their economic, industrial and sociocultural relevance.

Indeed, according to García González and Veiga Díaz (2009, p. 241), subtitled programming in Galicia is usually limited to festivals and film clubs that, although on the margins of the large film industry, have become an example of citizen empowerment and successful promoters of cultural projects - and, therefore, language projects - such as Numax:

examples of restoring closed cinemas, or those doomed to close down, have multiplied thanks to the citizen movements driving cinema cooperatives. The non-profit worker cooperative that manages the Cine Numax in Santiago de Compostela has had noteworthy success and has been acknowledged by the Consellería de Traballo with the award for the best cooperative project 2015. (Heredero & Reyes, 2018, pp. 57-79)

Therefore, two significant consequences can be inferred from the abandonment of the responsibilities entrusted to the CRTVG:

industrial responsibilities, as the diminished Galician business sector specialising in audiovisual subtitling - a sector mainly based in big cities such as Madrid and Barcelona - barely finds support in the limited demand of the CRTVG;

also, sociocultural responsibilities, since, as noted by García González and Veiga Díaz (2009, pp. 241-242), translation and subtitling in the CRTVG appear to be primary tools in language normalisation strategies.

The Galician case is an example, according to García González and Veiga Díaz (2009, pp. 244-245), of how audiovisual companies prioritise the use of the Castilian language as a filming or recording language, retrospectively dubbing into Galician for its screening in cinemas located in Galicia or for its broadcast on the CRTVG. It is a practice that finds its institutional endorsement in the diffuse definition of “Galician audiovisual work” by AGADIC, the Axencia Galega das Industrias Culturais (http://www.agadic.gal/): one that broadcasts more than 75% of its dialogues or its narration in the Galician language. The results of such a regulatory lack of definition are meaningful: of the 12 projects supported in 2017 by this public agency, only five of them substantiate the use of Galician as the exclusive filming language.

As indicated by Ledo-Andión et al. (2016, pp. 322-323), AGADIC now takes over the management and promotion functions of the audiovisual sector in Galicia. AGADIC was created by a progressive government during the period 2005-2009, imposing a management model based on the relationship with the client of the audiovisual sector. This model, based on Law 6/1999 (Lei 6/1999, 1999) proclaims the protection of the linguistic identity of the audiovisual work but encourages the use of dubbing in those audiovisual works that request public subsidies. Consequently, audiovisual dubbing in post-production increases by not requiring the Galician language in the entire audiovisual production process.

The failure of Law 6/1999 does not extend only to subtitling, but also to dubbing: 1 decade after implementing the regulation, García González and Veiga Díaz (2009, pp. 245-248) describe how the pyrrhic distribution of copies dubbed into Galician, barely covering the six main cities in Galicia, creates an outlandish situation for the Galician language, perpetuating its status as a minoritised language.

Two decades after the enactment of Law 6/1999, the 5º Informe Sobre el Cumplimiento en España de la Carta Europea de las Lenguas Regionales o Minoritarias, del Consejo de Europa 2014-16 (5th Report on the compliance in Spain of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, of the Council of Europe 2014-16), is remaining silent on the subject of the relevance of subtitling audiovisual and film in the Galician language, while the practice of dubbing is limited to the Television of Galicia (Ministerio de la Presidencia y para las Administraciones Territoriales, 2017, p. 106).

Regarding the case of Catalonia, a “Stateless Nation” (Schlesinger, 2000, pp. 19-20), which has a population of more than seven and a half million inhabitants, 1 year after the approval of Law 1/1998, of January 7, on language policy, only 2.12% of the total of the tickets sold in Catalonia corresponded to “films in Catalan”: a label that included both those filmed in Catalan and foreign productions dubbed into this language (Martín-Alegre, pp. 11-12). A disconcerting starting point, since, although the profile of the predominant cinemagoer in Catalonia is somebody who has been schooled in Catalan, they do not seem to opt for watching films in this language - be it in OV, OVS or dubbed - a fact that made it impossible to achieve the objective of 50% of cinemas with screenings exclusively in Catalan, which was the purpose of Law 1/1998 (Martín, 2005, pp. 8-9).

The Generalitat de Catalunya decided to expand the case study on works eligible for subsidies, going on to recognise as “Catalan cinema” any film whose vehicular language was Catalan, in addition to those produced in its industrial network. This controversial financial support by the Generalitat of the dubbing of Hollywood productions, leading to the increase of the consumption of audiovisual works in Catalan regardless of its origin, could only prove its effectiveness in the long term.

Indeed, almost three decades after the implementation of this package of measures by the Generalitat, the report by the Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya (2016) indicates that of the total box office revenue (686) in 2016 (€122.460.000), €11.134.000 correspond to Catalan films, compared to €8.804.000 for films from the rest of Spain, with a box office revenue amount for the screening of foreign films of €102.387.000.

The issue to be challenged regarding these policies is the pre-eminence of dubbing over subtitles that - to satisfy commercial and industrial rather than cultural criteria - violates the spectator’s right to enjoy the film in its original narrative, stylistics, acting and linguistics, while revealing the weak commitment of administrations in their pledge to the normalisation of their respective languages: “not even the best-quality dubbing (...) can avoid manipulating dialogue in the translation and adjustment processes” (Martín-Alegre, 2005, p. 21).

In fact, in June 2017, the Catalan press (Nerín, 2017) echoed the question raised by the president of the Acadèmia del Cinema Català, Isona Passola, to the Catalan Parliament about the critical situation of Catalan cinema: only 20 of the 65 Catalan films produced in 2016 had been originally made in Catalan, which represented 31%; likewise, only 0.7% of the films shown in Catalonia had been shot in Catalan. Thus, since there is a prevalence in the filming of using Castilian Spanish (45%) and a gradual consolidation of English (15%), the filmmaker requested a specific policy from the Generalitat to support productions made entirely in Catalan.

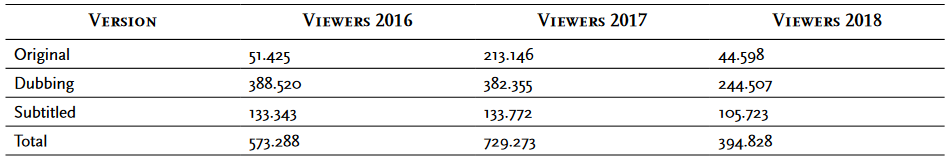

In this sense, the data on viewers distribution according to the type of audiovisual version, between 2016 and 2018 (Table 2), is very eloquent, according to Caballero-Molina and Jariod (2019, p. 216), with a clear preference for audiovisual dubbing.

Having defined the radical differences between the Galician and Catalan model, we can find a midpoint in the model of the Basque Country: a “Stateless Nation” (Schlesinger, 2000, pp. 19-20), which has a population of more than two million people, with a formula halfway between the dubbing empire and the occasional subtitling practices, albeit with very modest results. As described by Deogracias and Amezaga (2016, p. 694), with the implementation of the “Zinema Euskaraz” programme by the Basque government, since 2010, an average of 30 films have been shot in the Basque language - including fiction, documentaries and animation - broadcast with subtitles in Spanish in Basque cinemas and dubbed into Spanish for the Spanish market. Likewise, since 2012, a yearly average of between 12 and 14 films have been dubbed into Basque, aimed at children and adolescent audiences. The screening of films in Basque would have a minimal presence in overall ticket sales, in a ratio of one to 30, so the deployment of dubbing combined with subtitling still fails to achieve optimal results: “and that is precisely one of the problems of cinema in minority languages, beyond the output quantity: access to a large enough public to make the investment profitable” (Deogracias & Amezaga, 2016, p. 694).

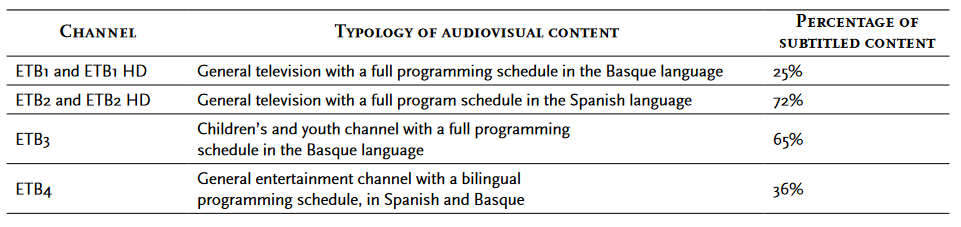

According to the data obtained from the response in the Basque Parliament to an interpellation of the political party EH Bildu, in 2019 on Basque television (Euskal Telebista or ETB, created by Law 5/1982, of May 20, as “Basque Radio Television Public Entity”; Euskadi Osorako Erabakiak, 1982) a total of 25 hours of audiovisual content were dubbed, while in 2020 increased to 66. Regarding the proportion of subtitled content throughout 2020, the consolidated data varies depending on the channel (Table 3).

ETB’s goal is to achieve a 90% subtitling percentage in all its channels. Another of ETB’s strategic objectives is the preferential subtitling of audiovisual content aimed at the youngest: thus, of the 246 hours subtitled in 2020, 184 had young people as recipients, compared to 62 aimed at adults.

At this point, a major question arises: would it be possible to extrapolate the three cases analysed, located in the Iberian Peninsula, to the complexity of the European audiovisual reality? Indeed, the three cases analysed share a transcendental problem regarding heritage and commercial aspects in the EU audiovisual policy: a redefinition of the film’s nationality.

In October 2005, the General Conference of Unesco held in Paris approved the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005). Two years later, the Eropean Union proceeded to ratify the Paris Convention (Lévy-Hartmann, 2011, p. 1), emphasising the defence of a European culture understood as a diverse fact and incorporating a strict formalisation of cultural promotion and safeguarding in all community trade agreements (Crusafón i Baqués, 2012, p. 1). Thus, in audiovisual matters, a European positioning strategy was promoted on a global level that, through bilateral alliances, openly challenged the chronic prevalence of the United States and some emerging countries.

Let us pause at this point to analyse an interesting paradox: if, with the ratification of the Paris Convention, the European Union countries jointly promote an intensive and expansive foreign policy of their culture understood as a differentiating factor, why, then, have certain “Stateless Nations” (Schlesinger, 2000, pp. 19-20) located territorially within the European Union been driven to enact particular protection regulations on the distribution and the exhibition of those films produced in their respective vernacular languages?

The question confronts us full-on with a debate as urgent as neglected on the European audiovisual scene. A debate that, although it is understood to have been overcome in political and administrative terms - fundamentally concerning the management of audiovisual rights -, is still a hot topic in cultural and linguistic terms: we are referring to the definition and institutional recognition of the nationality of the audiovisual work.

In practice and up to now, the granting of community protection and subsidies to a specific film depends on its “definition of Europeanness”: thus, in the audiovisual field, we find two legal references, the European Convention on Transfrontier Television, passed by the Council of Europe in 1989, and the Audiovisual Media Services Directive, in force since 2010, although amended in 2016 (Directive (EU) 2018/1808, 2018; European Convention on Transfrontier Television, 1989).

Beginning with the European Convention on Transfrontier Television, the consideration of “European films” is granted to both productions and co-productions managed by European individuals or legal entities (Azpillaga y Idoyaga, 2016, pp. 6-7), implementing a percentage criterion linked to their fiscal residence.

On the other hand, the articulated Audiovisual Media Services Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/1808, 2018) recognises as “European” all audiovisual works from one of the European Union member countries, as well as other signatories of the European Convention on Transfrontier Television, provided that:

at least 51% of the financial or personnel contribution is from the European Union;

the non-European Union states that are beneficiaries of the directive undertake, in reciprocal mutuality, not to discriminate against genuinely European audiovisual works or the result of the convention on transfrontier television;

films not from the countries above are framed in bilateral co-production agreements, provided the first criterion is met.

Now, in what way are the aforementioned generic criteria implemented in specific community promotion and subsidy measures? And no less important, are there significant differences, or even obvious contradictions, between the European regulatory framework and its transpositions in each of the member states?

As Katharine Sarikakis (2014, p. 55) warns, the success of the European project is based on the resignation of the nation-state to the former’s sovereignty and jurisdiction over a variety of political areas. Similarly, Eva Nowak (2014) argues how regulation and deregulation in European media policy generated “negative integration” (by removing national barriers to promote the free movement of products and services) and a “positive integration” (by encouraging market regulation through harmonisation of European policies; p. 97).

Before untangling the Gordian Knots outlined, it is advisable to undertake a careful review of EU Regulation of no. 1295/2013 the European Parliament and of the Council, of December 11, 2013, establishing the Creative Europe Programme (2014 to 2020) and repealing Decisions no. 1718/2006 /EC, no. 1718/2006 /EC, no. 1041/2009 / EC (Regulation (EU) No 1295/2013, 2013): within it, the MEDIA subprogramme reserves the status of a “European company” to those established in European Union territory, owned by citizens residing in the EU Member States, the European Free Trade Agreement or other countries participating in MEDIA.

Regarding the core theme of this paper - subtitling - Azpillaga & Idoyaga (2016, pp. 12-13) highlights in the MEDIA subprogramme its declared will to protect linguistic and cultural pluralism, with clear positive discrimination towards those companies and productions from countries and regions with low production potential or belonging to reduced language and/or geographical areas.

However, each member state’s legislation has added further aspects to the initial consideration of “European work”, such as the requirement of a “certificate of nationality” used to calculate screen shares. The system of subsidies and aid to cinema managed by the Spanish government describes the requirements for obtaining this (Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, 2019). Those include the “preferential” production of the OV in any of the official languages of the state should be highlighted: a preferential criterion, although not exclusive, that does not include the obligation to maintain the original language option in the screening of the film.

Regarding the calculation of screen shares, Article 18 of the Spanish Film Law (Ley 55/2007, 2007) stipulates a minimum screening fee of 25% of community films on the total volume of films screened in the cinema. In contrast, Article 29 decrees the aid to those cinemas with a diverse film offer: even, in collaboration with the Autonomous Communities, specific support measures are contemplated for those independent cinemas that, in their annual programming, include a proportion of Latin American and EU feature films that is larger than 40%, prioritising those with exclusive screenings in OV. Likewise, Article 29 contemplates grants of up to 50% - chargeable to the cost of printing copies, subtitling, advertising and promotion, technical means and resources that facilitate access to groups with sensory disabilities - to those independent cinemas that, for a continuous time of no less than 3 weekends, programme feature films from Europe and Latin America in OV.

As a corollary to this section and in order to complete this intricate regulatory medley - ranging from EU regulation to a jumble of particular transpositions in the different EU states- we will now turn to sub-state protection systems exemplified in two antagonistic legislative models:

On the one hand, and as previously mentioned, Galicia has a general framework for protecting its own productions and the use of the Galician language in the audiovisual field through its Law No. 6/1999, of September 1, from Audiovisual de Galicia. However, such legislation lacks a subsequent regulatory development, except for the law destined for publicly owned media - Law No. 9/2011 of November 9, on the Public Media of Audiovisual Communication in Galicia. Nevertheless, even when it promotes the timely protection of a language pattern, it foregoes a detailed development of the said regulatory model on the audiovisual field understood in all its amplitude: from ideation and production to exhibition or distribution.

On the other hand, and in contrast to the previous model, Catalonia has idiosyncratic and developed regulations - ones that detail the protection quotas for the distribution and the exhibition of films in Catalan - based on the specific law of language normalisation of Catalan (Law No. 7/1983, of April 18 and Law No. 1/1998, of January 7, on language policy; Lei 1/1998 , 1998; Lei 7/1983, 1983). The Generalitat de Catalunya has articulated a profuse battery of provisions covering the entire value chain of audiovisual content - from ideation to production, post-production and distribution or exhibition - ranging from rating the works to registering companies even those going through the filming notification protocol. For all these reasons, Catalonia constitutes a benchmark among the various “Stateless Nations” (Schlesinger, 2000, pp. 19-20) that, in practice, limit their activity to the deployment of requests for grants or to representing the Instituto de la Cinematografía y de las Artes Visuales in limited budget protection actions mainly geared towards distribution and screening.

5. Conclusions and Discussion: Key Challenges and Recommendations to Provide Europe With a Film-Subtitling Protocol

“The best media policy is no media policy”. This unambiguous dictum is associated with the late Rudolf Augstein, journalist, founder and longstanding editor-in-chief of Germany’s most important news magazine, Der Spiegel. He came from and worked in a large European state, and he was a furious defender of press freedom. Would he have modified this statement when confronted with media realities in a small state, eventually being part of a larger language area with one large country dominating the area? (Trappel, 2014, p. 239)

As mentioned above, one of the main difficulties in assessing the effectiveness of a specific cultural policy is that only in the long term can it prove its success or ineffectiveness, most of the time when it is already too late to consider strategic repositioning (Sanz, 2011).

In the different European case studies analysed, we have shown the political-regulatory comparison between dubbing and audiovisual subtitling and the prevalence of dubbing in terms of subsidies. And all this despite:

in strictly commercial terms, the average cost of subtitling is 10 times lower than the average cost of dubbing;

in artistic terms and contrast to dubbing, subtitling does not infringe on but rather consolidates the spectator’s right to enjoy work in its original integrity.

Consequently, one of the recommendations to endow Europe with a film subtitling in non-dominant languages protocol urges European political-regulatory action to transcend that short-term satisfaction of inveterate consumption habits anchored in dubbing instead of promoting its renewal through long-term educational and cultural policies. Policies to guarantee the intimate experience between the viewer and the audiovisual story in its original language, either through the OV - when language proficiency allows it - or through OVS.

Another problem repeatedly isolated in our analysis points on the need to vary the causal focus of the reduced projection of cinema in minoritised languages, replacing the merely commercial perspectives - which claim a shortage of the demand of the potential public - by other cultural ones, which point to the scarcity of supply, visibility and accessibility to this type of content, due to an unstable distribution and broadcasting network.

It is appropriate to introduce here a contrapuntal reflection at the hands of Philip Schlesinger (2016), who, in the framework of reviewing the concept of “creative economy”, shows his concern for the consolidated conception of culture subordinated to economic considerations:

The idea of the creative economy has increasingly obscured and crowded out conceptions of culture that are not in some way subordinate to economic considerations. Intelligent policy-makers and smart government advisers know that this is so and that their evidence rests on uncertain grounds -at least, that is what they tell me privately. What figures in such conversations does not, on the whole, enter the public domain because the expedient argument that turns culture into economic value is seen as the only really comprehensible and sellable formula in our times. That is one of my conclusions from empirical research on and engagement in this topic. (p. 189)

All this in a context of the prevalence of distribution and exhibition in cinema GVC, which explains the exponential increase in the number of niche markets and the inevitable relegation of the movie theatre to a residual role - more as a “vintage symbol” than as a source of profitability - so it is worth insisting on two considerations:

neither OV nor OVS hamper the screening process, being forms of communication that perfectly overlap in the process of digitalising cinemas;

audiovisual subtitling guarantees the integrity and linguistic originality of the work in question, and it also guarantees understanding to all those without competence in that language.

Hence our strong recommendation to the different European public administrations, along with Deogracias and Amezaga (2016, p. 707), of the need to encourage - beyond traditional subsidising policies - a new concept of “linguistic accessibility”: a capacity that would have to be based on a firm commitment to the expansion of cultural competences at European level, so that their citizens become accustomed to cultural fruition conveyed by non-dominant languages, perceiving the European linguistic diversity, no longer as a barrier to be avoided, but as a priceless intangible cultural heritage to vindicate.

Accordingly, as the methodological section of this article ventured, the application of the Delphi technique allowed a contrast of significant conclusions, based on the degrees of consensus (C <0.2) existing on the expert panel, that can be synthesised in six key challenges and recommendations:

The OVS constitutes the best antidote against the linguistic disintegration of the original audiovisual work.

The production costs of audiovisual dubbing are 10 times higher than the OVS costs.

Unlike audiovisual dubbing, OVS protects the original integrity of audiovisual work.

European linguistic diversity should not be seen as cultural barriers but rather as opportunities for enriching the European Cultural Heritage.

It is an urgent duty of the Council of Europe to redefine the nationality of the audiovisual work based on its original linguistic choice.

The coordinated action of communication policies will demonstrate the close relationship between VOS promotion and the linguistic normalising process.

Likewise, we request, from the Council of Europe - as a supra-state entity that coordinates the actions of the European Union states - an urgent redefinition of the concept of “nationality of the audiovisual work” essentially linked to the original linguistic choice from its conception and production, instead of the number of territorial settlement percentages involved in its funding and human resources, currently in force at both the European Convention on Transfrontier Television in 1989 and the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (Castelló-Mayo et al., 2018, p. 41).

The protocol to be adopted by the European Union should also assume a prospective eagerness for the formalisation of those emerging formats, although usually inspired by film works: thus, we understand that, in the expansive field of the videogame industry, the implementation of concrete and stable actions so belligerent against linguistic intrusion as guarantors of the most vulnerable cultural identities:

it is rather usual to find foreign words in Spanish; in many cases, they eventually become a part of the language, sometimes adapting them to Spanish phonology and grammar (borrower words). Especially, the video game industry is full of English terms that are not translated due to the late entrance of the word in the Spanish market. (Méndez-González, 2014, p. 197)

Nor must we forget, considering the implementation of a protocol to encourage subtitling in non-dominant languages, that their status often hinders the internal and external projection of minoritised languages as “target languages”, that is, vehicular languages for subtitling or dubbing. To a lesser extent, they are manifested as “source languages”, that is, as languages subject to translation: a problem that explains the extreme vulnerability of these minoritised languages in the light of the influence of other languages with a linguistic corpus more consolidated and settled by its preponderant condition.

Finally, we will point out as one of the unexplored niches in this article (which we hope to return to in future publications) the potential of subtitling in the integration of citizens with specific sensitive disabilities in non-hegemonic languages:

another challenge concerns the issue of media accessibility. This type of inclusion means that more investment is needed in services such as subtitling for the hearing impaired or descriptions for the visually impaired. Indeed, some participants pointed out that media accessibility is not sufficiently balanced in Europe and varies from country to country. This imbalance is even accentuated when it comes to accessibility for minority languages, which represent the majority of languages in Europe. (European Audiovisual Observatory, 2020, p. 15)

As a corollary to what has already been said, let us insist on the impossibility of a non-dominant minority language renouncing any standardisation tool within its reach, let alone the film subtitle. Film subtitles can make accessible one of the most dominant discourses in our contemporaneity, either for its external projection or for its internal establishment in its original community.

texto em

texto em