Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.40 Braga dic. 2021 Epub 20-Dic-2021

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.40(2021).3503

Articles

The Invisible Implications of Techno-Optimism of Electronic Monitoring in Portugal

iCentro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

Nos últimos anos, a supervisão de ofensores nas comunidades tem-se vindo a constituir como uma nova faceta da paisagem penal na maioria dos países ocidentais, assistindo-se ao seu crescimento em escala, alcance e intensidade. Em Portugal, a par das penas e medidas na comunidade e das penas de prisão, destaca-se a vigilância eletrónica como forma de monitorizar ofensores. Este instrumento penal é associado a elevadas expectativas criadas por discursos políticos e mensagens mediáticas que retratam a vigilância eletrónica como um instrumento que permite reduzir a sobrelotação e a pressão sobre o sistema prisional e os custos associados. Ao mesmo tempo, também é argumentado que, ao manter os ofensores na comunidade, a vigilância eletrónica favorece igualmente a manutenção dos laços sociais, evita os potenciais efeitos criminógenos da prisão e facilita os processos de ressocialização. Neste artigo, inspirando-me nos estudos sociais da ciência e tecnologia e nos estudos da vigilância, exploro as implicações invisibilizadas do tecno-otimismo em torno da vigilância eletrónica em Portugal. Por via de análise documental, baseada em audições parlamentares, peças jornalísticas, artigos de opinião, relatórios oficiais e literatura científica, reflito sobre a forma como o tecno-otimismo tem invisibilizado a ampliação da malha penal; implicado a cooptação da família na esfera penal e a transmutação do espaço doméstico num espaço de reclusão; e, no que concerne à violência doméstica, a caracterização deste flagelo social como tendo uma solução tecnocientífica, estreitando, assim, o debate público sobre a sua prevenção.

Palavras-chave: tecno-otimismo; vigilância eletrónica; malha penal; família; violência doméstica

In recent years, offenders’ supervision has emerged as a new facet of the penal landscape in most Western countries, growing in scale, reach and scope. In Portugal, in addition to community sanctions and prison sentences, electronic monitoring stands out as a way of monitoring offenders. This penal instrument is associated with high expectations created by political discourses and media messages that portray electronic monitoring as an instrument that enables the reduction of overcrowding and pressure of the prison system and its costs. In addition, it is also argued that, by maintaining offenders in the community, electronic monitoring also favours the maintenance of social ties, avoids the potential criminogenic effects of prison, and facilitates resocialisation processes. In this article, drawing inspiration from social studies of science and technology and surveillance studies, I explore the invisible implications of techno-optimism of electronic monitoring in Portugal. Through documentary analysis, based on parliamentary hearings, media pieces, opinion articles, official reports, and scientific literature, I reflect upon how techno-optimism makes the expansion of the penal sphere invisible. Moreover, techno-optimism about electronic monitoring in Portugal also implies the co-optation of family in the criminal sphere and the transmutation of the domestic space into a confinement space. Regarding domestic violence, techo-optimism around electronic monitoring also contributes to the characterisation of this social phenomenon as having a technoscientific solution, thus narrowing the public debate on its prevention.

Keywords: techno-optimism; electronic surveillance; penal sphere; family; domestic violence

1. Introduction

In 2012, as part of the fieldwork I developed in the prison context for my PhD thesis, I talked to a prisoner who worked in the bar dedicated to professionals and prison’ external members. During the breaks from the strenuous consultations of judicial and criminal proceedings, the conversation with prisoners who circulated in the prison’s administrative area was a balm that I enjoyed voraciously. In one of those conversations, the prisoner who used to serve me coffee as soon as I entered the bar briefly told me his life story. Among several other things, he shared that he had already been “imprisoned at home”, under the electronic monitoring system, before entering the prison in which we were, at the time one of the most overcrowded in the country, in a year in which the official overcrowding record was the second-highest in the decade (112.7%; PORDATA, 2021). My curiosity skyrocketed. Of all the interviews I had carried out so far, none of the interviewed prisoners had been under electronic monitoring. My first instinct, already marked by several months of fieldwork in prisons, where I saw many episodes and heard many reports that reflected the hardness and “pains of imprisonment” (Sykes, 1958), was to consider that this would have been a calmer period. I replied, “it must have been a lot better than being here now”. Looking at me with an expression that reflected how naïve he considered me to be, the prisoner kindly responded, “no. You can’t imagine what it’s like to be imprisoned at your own home. With freedom on the other side, without being able to reach it”.

In the almost 10 years that separate me from this fieldwork experience, I have never forgotten this conversation. It comes to my memory whenever I read and hear representatives of public entities praising the “humanising” effect of the electronic monitoring system (Caiado, 2014), considered by the highest officials of the administration of justice in Portugal “one of the best in the world” (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, 2020, para. 3). I also recall this interaction every time I read or hear about the most recent statistics on electronic monitoring, showing an evident expansion of this instrument in recent years (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, n.d.-e). The apparent contradiction between this prisoner’ narrative and the dominant discourse, based on techno-optimism (Quinlan, 2020), leads me to question in this article, through a historically and sociologically informed scepticism (Benjamin, 2019, p. 26), the use of electronic monitoring in Portugal.

In recent years, supervision of offenders in communities has emerged as a new facet of the penal landscape in most Western countries, growing in scale, reach, and intensity (Hucklesby et al., 2021; Laurie & Maglione, 2020; McNeill & Beyens, 2013; Nellis et al., 2013). In Portugal, in addition to community sanctions and prison sentences, electronic monitoring stands out as a way of monitoring offenders. This penal instrument is associated with high expectations created by political discourses and media messages that portray electronic monitoring as an innovative and effective way of dealing with issues of crime and public safety and as a mechanism that allows reducing overcrowding and pressure on the system prison, as well as its associated costs. In addition, it is also argued that, by maintaining offenders in the community, electronic monitoring also favours the preservation of social ties, avoids the potential criminogenic effects of prison, and facilitates resocialisation processes (Caiado, 2014; Martins, 2019). However, such widely shared arguments lack confirmation as few studies explore in-depth the effectiveness, functions, and implications of this penal instrument (see in this regard Baiona & Jongelen, 2010; Lopes & Oliveira, 2016).

In this article, drawing inspiration from social studies of science and technology and surveillance studies, rather than debating the efficiency of the electronic monitoring system in Portugal, I aim to explore how socio-technical imaginaries (Jasanoff & Kim, 2015) around this penal instrument reflect a broad techno-optimism (Quinlan, 2020). More particularly, I reflect upon how techno-optimism has made invisible (a) the expansion of the penal network; (b) the co-optation of the family in the penal sphere and the transmutation of the domestic space into a space of confinement; (c) and, concerning domestic violence, the characterisation of this social phenomenon as having a technoscientific solution, thus narrowing the public debate on its prevention.

2. Electronic Monitoring in Portugal: Historical Background and Expansion

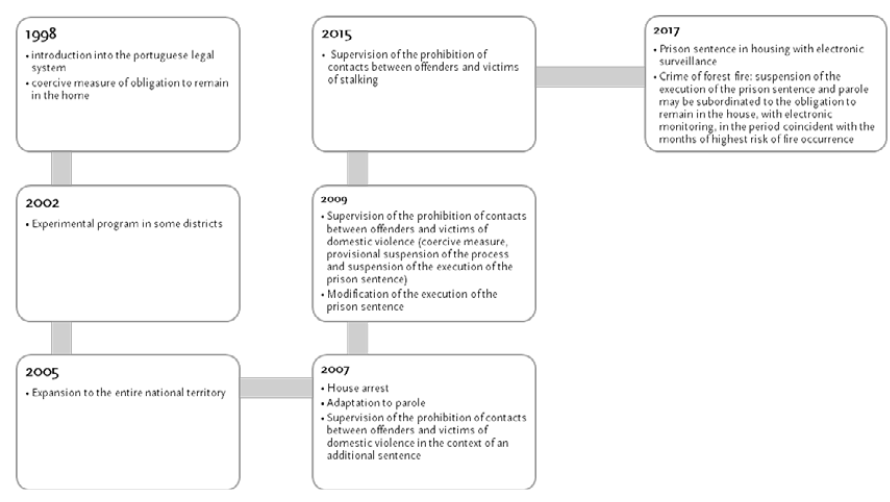

Electronic monitoring was introduced into the Portuguese legal system with the amendment to the Criminal Procedure Code of 1998, which associated it with controlling the coercive measure of obligation to remain in the home to establish an alternative to pre-trial detention. However, it only started to be implemented in 2002 as part of an experimental program in some districts. In 2005, a specialised network of electronic monitoring services was created in Portugal, which allowed the usage of this technology in all the national territory.

In 2007, electronic monitoring also became associated with house arrest (execution of prison sentence at home) and with the adaptation to parole and the supervision of the prohibition of contacts between offenders and victims of domestic violence in the context of an additional sentence. In 2009, the supervision of forbidden contacts between offenders and victims of domestic violence was extended to the context of a coercive measure, provisional suspension of the process, and suspension of prison sentence enforcement. In the same year, with the approval of the Código de Execução das Penas e Medidas Privativas da Liberdade (Code for the Execution of Sentences and Measures that Deprive Individuals of Liberty), electronic monitoring also became an instrument available to supervise the modification of the execution of the prison sentence for cases of prisoners with illnesses, disabilities, or of old age. In 2015, electronic monitoring was extended to the supervision of the prohibition of contacts between offenders and victims of stalking (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, n.d.-f).

Finally, the legislative review carried out by Law No. 94/2017 of August 23 (Law n.º 94/2017, 2017) determined the elimination of the penalty of imprisonment for free days and semi-detention, giving the possibility of cases in execution being turned into house arrest sentences. That is, it determined that house arrest with electronic monitoring should be used, with the possibility of the monitored individual leaving to attend resocialisation programs, educational or professional activities or other obligations appropriate to his/her social reintegration process. This same legislative review also provides that, in the context of forest fire’ crimes, the suspension of the execution of the prison sentence and parole may be subordinated to the obligation to remain at home, with electronic monitoring, in the period coincident with the months of highest risk of fire occurrence (Figure 1; Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, n.d.-f).

Figure 1: Source. Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (n.d.-f) Regulation of electronic surveillance in Portugal

In this sense, Law No. 33/2010 of September 2 (Lei n.º 33/2010, 2010) currently prescribes that electronic monitoring can be used: (a) to ensure compliance with the obligation to remain at home (applied as an alternative to preventive detention); (b) in the execution of a prison sentence under a regime of house arrest; (c) as an adaptation to parole (referring to the anticipation of parole for a maximum period of one year); (d) to modify the execution of the prison sentence; (e) to monitor the prohibition of contacts between defendants/convicts and victims of domestic violence and stalking; (f) to guarantee the obligation to remain at home in cases of individuals convicted for forest fire’ crimes. Due to its “chameleon” character, electronic monitoring is applied at different stages of involvement with the criminal justice system, used in different ways, with multiple goals and in a wide variety of criminal sanctions. This diversity is not exclusive to the Portuguese context, as it is also found in other countries (Beyens, 2017; Dünkel et al., 2017; Hucklesby et al., 2021).

The Portuguese law prescribes that electronic monitoring does not entail any financial costs for the defendants or convicted individuals and depends on their consent and those who cohabit with them (if over 16 years of age). The national electronic monitoring system uses two different types of technology: radiofrequency and geolocation. Radiofrequency technology is used in cases of house arrest and geolocation in cases of the supervision of the prohibition of contacts between offenders and victims of domestic violence and stalking (it monitors two people simultaneously, offender and victim). In the latter case, referring to geolocation in cases of domestic violence and stalking, the judicial authorities define the victim’s protection zones (such as, for example, home and workplace) and its radius, which can be adapted by the electronic monitoring services depending on the circumstances of those involved, namely profiles, routines, and geographical constraints. The offender is assigned a personal identification device (electronic bracelet) and a mobile positioning unit that establishes a relationship with the global positioning system (GPS). The victim is also assigned a “protection unit” device, which “must always be carried by the victim and establishes a GPS connection” (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, s.d.-a, p. 2). This protection unit device is not connected to the victim’s body. They are recommended to carry it, but not obliged. The electronic monitoring services monitor and detect possible approaches of the offender. If he/she approaches or enters the exclusion zones, the victim is informed, and the offender is automatically alerted and can be questioned by the electronic monitoring services. Electronic monitoring services contact police forces to provide protection and support to the victim, if necessary.

According to the latest available data, as of December 31, 2020, 2,432 penalties and measures were monitored in the national territory through electronic monitoring services. Amongst the penalties and measures applied, the following stand out: supervision of the prohibition of contacts between offenders and victims of domestic violence (prohibition of contacts by geolocation; 54.23%), obligation to remain in the home in cases of individuals convicted for crimes of forest fire (22.28%) and house arrest (19.94%; Direção-Geral da Política de Justiça, n.d.).

According to the last available report of the General Directorate of Reintegration and Prison Services (Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, n.d.-c), referring to the year 2019, radio frequency had a cost of €6.33 per day and radio frequency €8.24 (per monitored person). The revocation rate, relating to penalties and measures and penalties revoked due to non-compliance (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, n.d.-b), between 2013 and 2018, was between 2.80% and 3.60%, with no data available for the year 2019.

The organisational structure of the National Electronic Monitoring System comprises a national control centre located in Lisbon, and 12 territorial teams, which in 2020 comprised 141 professionals, including 12 team coordinators, 24 senior technicians, 100 social reintegration’ technicians and five technical assistants (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, 2020). In 2021, reinforcing its commitment to this technology, the Ministry of Justice, through the General Directorate of Reintegration and Prison Services, signed, with effect from March 1, a new contract to ensure the provision of electronic monitoring services for execution of court decisions for the period between 2021 and 2024 (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, 2021).

3. Analytical Perspectives

This article is at the intersection of two interrelated fields of study, surveillance studies and science and technology social studies. Surveillance studies aim to problematise the multiple forms, motifs, and consequences of monitoring, supervising and governing populations (Frois, 2013; Fuchs, 2011; Lyon, 2002, 2003, 2018; Marx, 2002; Staples, 2014). Focusing both on spatially defined locations, such as airports, prisons, and companies, as well as on the digital context, such as social networks or databases, this field of study highlights how surveillance can interfere and condition (sometimes without knowledge or consent) civil rights such as freedom, privacy, and confidentiality (Frois, 2015). We are in a context strongly marked by the expansion and intensification of surveillance - massively strengthened after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States of America (Lyon, 2003) - and by neoliberal corporate regimes, which increasingly subjugate several spheres of social life (Dardot & Laval, 2016; Harvey, 2005; Mirowski, 2019). Thus, contemporary modes of surveillance constitute mechanisms of social sorting that verify identities while assessing risks, thus contributing to discrimination and, in some cases, segregation of individuals and groups (Lyon, 2002).

Within this body of literature, William Staples (2014) frames electronic monitoring as a type of “participatory monitoring” in which people who are subject to such measures also have the task of actively participating in their own surveillance. According to the author, as to Bentham’s panoptic model, electronic monitoring allows constant movement surveillance. However, this type of power operates in a more incisive way:

instead of subjecting the body to a regimented system of institutional discipline and control, this disciplinary technology is located on the body itself. Disciplinary power then has been deinstitutionalized and decentralized. And unlike the somewhat primitive panoptic tower that could practically view only a limited number of cells, this cybernetic machine is capable of creating an infinite number of confinements. (Staples, 2014, p. 84)

In the wake of Michel Foucault’s (1975) analytics of power, electronic monitoring follows new principles of disciplinary power. Electronic monitoring is part of a modern discourse (normalising but eminently optimistic) that establishes it as an efficient technique (economically, politically, and morally) through which power systems aim and produce the singularisation and subjection of individuals. Such devices, operating through invisibility, place the body as a target of power (Morais, 2014).

Social studies of science and technology is an interdisciplinary field that studies the production, distribution and use of scientific knowledge and technological systems and the consequences of these activities for different groups (Jasanoff, 2004; Latour, 1987, 2000; Latour & Woolgar, 1986; Law, 2008; Lynch, 2012). Within this field of studies, it is evident that technologies, commonly considered as “neutral”, objective, scientific and conducive to social progress, are imbued in social norms and ideologies that are a constitutive part of their creation, development, and implementation, therefore, reinforcing various forms of inequality (Benjamin, 2019).

From this body of literature, the concept of socio-technical imaginaries proposed by Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim (2009) as “collectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfilment of nation-specific scientific and/or technological projects” (p. 120) is particularly useful. Conceptualising imagination as a social practice, the concept of socio-technical imaginaries refers to socially shared imaginaries that guide how we think and make decisions at the individual and the collective level (Jasanoff & Kim, 2009, 2015). Thus, socio-technical imaginaries include not only widely shared belief systems but also notions that prescribe what is desirable, constituting “aspirational and normative dimensions of social order” (Jasanoff & Kim, 2015, p. 5). Therefore, socio-technical imaginaries are rooted and inscribed into institutions, culture, and artefacts, constituting a shared vision of a future achievable through advances in science and technology (Jasanoff & Kim, 2015).

As explained by Andrea Quinlan in her work on forensic rape kits in the United States of America (Quinlan, 2020), techno-optimism around some technologies has been co-constructed (Jasanoff, 2004) as a socio-technical imaginary anchored in the idea that science and technology can effectively solve complex problems in the criminal justice system. That is a socio-technical imaginary inscribed in institutions, culture, and artefacts (Jasanoff & Kim, 2009) and widely disseminated by the media, policymakers, activists and victims (Quinlan, 2020).

The concept of techno-optimism shares similarities with the term techno-solutionism, proposed by Evgeny Morozov (2013), anchored in the idea that technology, through its codes, algorithms, and infrastructures, can solve problems facing humanity. Morozov argues that this drive towards efficiency obliterates other avenues for approaching and solving social problems, leading to a context where tech companies, rather than democratically elected governments, determine the future’s shape. However, the focus on how business corporations own and control technologies presents stark differences from the case of electronic monitoring, whose legislation, implementation, and expansion has been promoted and controlled at the State level.

4. Socio-Technical Imaginaries Around Techno-Optimism in Portugal

In Portugal, socio-technical imaginaries around techno-optimism have broad historical, social, and cultural roots. Portugal is a country strongly marked by a long period of dictatorship in the 20th century (1926-1974), characterised by political and police repression and censorship (Pimentel, 2007; Ribeiro, 1995), which left a lasting mark on society and especially on the legal and criminal justice culture in Portugal. After the democratic revolution of 1974, and especially after Portugal’s admission to the European Union (1986), the Portuguese State mainly focused on investing in modernisation and progress, as a way of “catching up” other countries, considered more technologically advanced (Amelung et al., 2020). According to Catarina Fróis and Helena Machado (2016),

in Portugal, the ideal of modernity and the fight against backwardness is so deeply rooted that it has been assimilated into a kind of official rhetoric, to the point where we could almost say it has become a national trait, readily identified by the Portuguese as a defining feature of the national character. (p. 396)

Therefore the emergence of electronic monitoring in Portugal is linked to these pre-existing and persistent socio-technical imaginaries that see modernisation through technological expansion and consolidation as an integral part of how Portuguese society is organised. Similarly to the implementation of closed-circuit television and the creation of forensic DNA databases in Portugal (Frois & Machado, 2016; Machado & Frois, 2014), electronic monitoring is also legitimised by socio-technical imaginaries rooted in the efficiency of technology in criminal justice institutions.

In addition to being anchored in cultural understandings that associate technology with efficiency, speed and neutrality, the techno-optimism around electronic monitoring is also reinforced by political and social concerns regarding prison’s overcrowding and high costs. Portugal is one of the countries with the highest imprisonment rate in the European Union, despite recent decreasing trends (World Prison Brief et al., n.d.). Furthermore, it is also one of the countries where the majority of prisoners serve most of their sentences. In the words of Catarina Fróis (2020), “in Portugal, there is much sentencing, for a long time, and this time is served up to the legally stipulated limit” (p. 28). Therefore, such organisation of the criminal justice system entails severe consequences for the Portuguese prisons, which are often overcrowded and largely degraded. In this context, as analysed below, the expansion of electronic monitoring use has been identified as one of the main ways of reducing pressure on prison services.

In this article, I critically explore the techno-optimism surrounding electronic monitoring in Portugal, outlining its invisible implications. Through this analysis, I illustrate how electronic monitoring has been presented and portrayed as a technological solution to a series of broad and complex social and criminal problems related to the governance of crime in its various aspects, namely, victim protection, imprisonment, and rehabilitation. More specifically, I look at how the techno-optimism around electronic monitoring has been limiting the questioning of the effects of electronic monitoring on the penal network expansion, the ideals on which it is anchored and promoted, and its implications within domestic violence (see also Quinlan 2020).

5. Invisible Implications

5.1. Expansion of the penal network

Two of the main arguments driving the implementation of electronic monitoring have been reducing pressure and overcrowding in the prison system and, consequently, reducing costs. That is pointed out in official documents and discourses, such as the speech by Rómulo Augusto Mateus, director of the general directorate of reintegration and prison services. At a parliamentary hearing within the scope of the Subcommittee on Social Reintegration and Prison Affairs of the Committee on Constitutional Affairs, Rights, Freedoms and Guarantees (Assembleia da República, 2020), Rómulo Mateus said that “it is fair to say that the electronic monitoring program we have, one of the most robust in the world, took around 2,000 inmates out of prison and that was what allowed the overcrowding to be lowered to below 100%” (33:24). The media widely disseminates such arguments, recurrently pointing to the (alleged) cost reduction provided by electronic monitoring systems. For example, thePúbliconewspaper, in 2019, published a piece entitled “Pulseiras Electrónicas Pouparam ao Estado Mais de 13,8 Milhões de Euros” (Electronic Bracelets Saved the State More Than 13.8 Million Euros; Trigueirão, 2019). This conclusion compares the daily cost of someone serving a sentence in prison (€44.88) and an individual under electronic monitoring in the radiofrequency regime (€8.24).

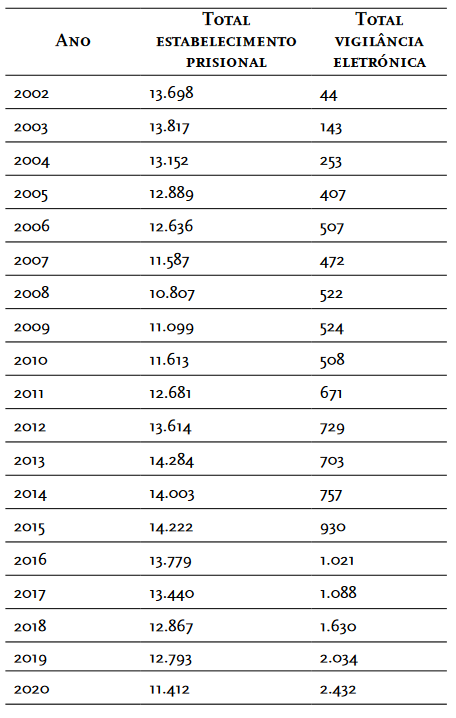

An in-depth analysis of the correlation between the prison population and individuals under electronic monitoring and the costs inherent to each of these measures is beyond this article’s scope. Nevertheless, a simple comparison between the evolution of the prison population over the last 19 years and electronic monitoring measures does not show an inverse linear relationship (Table 1). In other words, if electronic monitoring measures have been increasing, the prison population has been oscillating, sometimes increasing, sometimes decreasing. Therefore, based on these data, it is difficult to sustain the linear argument, so widely propagated, that the increase in electronic monitoring measures has been reducing the prison population.

Table 1: Evolution of prison population and electronic monitoring measures, on December 31 of each year

Source. PORDATA (https://www.pordata.pt/) and Estatísticas da Justiça (Justice Statistics; Direção-Geral da Política de Justiça, n.d.)

These data show how electronic monitoring is situated within a complex debate on the (dis)connections between imprisonment, alternatives to prison sentences and community measures. In 1975 Michael Foucault published Discipline and Punish, a work that, according to Mallart and Cunha (2019), focused more on the principles and technologies of disciplinary society than on prisons as institutions. Foucault predicted that, as prisons had turned physical punishments obsolete, they were also doomed to decline, within diffuse disciplinary rationality, characterised by more discreet and diversified mechanisms of “disciplinarisation” of society. Other authors followed Foucault in this prospective analysis. Allied to this idea was the trust in non-penal mechanisms, such as measures in the community (Cunha, 2008).

However, what happened was a more complex phenomenon: if, on the one hand, the use of alternative measures to prison increased, on the other hand, there was also an unprecedented growth of imprisonment rates (Wacquant, 2000). Within this simultaneous expansion, there has been a debate over to what extent mechanisms of offenders’ supervision constitute alternatives to imprisonment that effectively reduce the number of imprisoned individuals and/or constitute an additional response that further expands and diversifies the penal network (Cohen, 1985). That is, moving individuals between different agencies over time that echo and resonate with each other, in a configuration that Fábio Mallart (2019) calls an “archipelago”.

Some authors argue that we are not witnessing the bifurcation of the system whereby violent offenders would be subjected to imprisonment, and people who commit minor offences would be directed towards community measures and other alternatives to imprisonment, such as electronic monitoring. Instead, we see how the proliferation of sentencing and monitoring options ultimately leads to the movement of the same individuals between different agencies over time. That is a process that Roger Matthews (2013) calls “transcarceration”. As summarised by the author, “the proliferation of sentencing options creates a larger self-referential or autopoietic systems which recycle individuals through a more closely linked network of agencies” (Matthews, 2013, p. 9). Since it is possible to use electronic monitoring both as a front and back door of the prison, this system can expand the period of involvement of offenders with the criminal justice system. That is, both as an alternative to preventive detention and the modality of early release of prisoners through parole adaptation.

5.2. Co-optation of the Family in the Penal Sphere and Transmutation of the Domestic Space Into a Space of Confinement

In addition to the (alleged) decreased pressure and cost reduction within the prison system, another advantage pointed out in the use of electronic monitoring concerns the “preservation or resume of freedom and family and social ties, aspects that may constitute an important social asset in shaping behaviour and preventing recidivism” (Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais, n.d.-d, para. 1). Such arguments are also outlined by the minister of justice who, in an interview with the Público newspaper in October 2019, states that “the execution of short sentences outside the prison environment prevents the criminogenic effects of prison while favouring re-entry by keeping the convicted individual in his/her family environment and reducing the risk of recidivism” (Trigueirão, 2019, para. 27). This rationale is anchored in a trend increasingly disseminated in official discourses and in some studies that associate family support, during and after imprisonment - in coordination with social security, health, education, training, and employment - with “successful” social reintegration processes materialised, for example, in the decrease of recidivism rates (Berg & Huebner, 2011; Codd, 2007; Duwe & Clark, 2011; Naser & Vigne, 2006; Visher & Travis, 2003). In general terms, it is argued that offenders who maintain family ties during and after imprisonment tend to be more “successful” in the reintegration process, being less likely to remain involved in criminal activities after the end of their sentence (Baumer et al. , 2009; Mills & Codd, 2008).

This research is fruitful and capable of helping delineate policies to help maintain social ties. However, these studies do not enable the understanding of the complex and dynamic variables inherent to the interconnections between family support, socioeconomic conditions and social reintegration processes. As mentioned by Christy Visher and Jeremy Travis (2003), “whereas much of this research confirms the correlation between family ties and post-release success, it fails to address the more difficult issues that could lead to a full understanding of how and why this effect occurs” ( p. 102).

Even though these types of influences can, indeed, materialise in “successful” reintegration processes (i.e., avoiding recidivism), caution is needed when placing high expectations on the potential of families to assist processes of social reintegration (Codd, 2007; Mills & Codd, 2008; Touraut, 2012). First, not all families want and/or have the necessary conditions to welcome offenders and support and assist their reintegration. Generally, the idea that families are key elements in social reintegration involves the notion of households characterised by the sexual division of labour, non-criminal, non-violent, based on harmonious relationships and provided with the necessary monetary, housing, and social resources available to offenders. In other words, “it is the ‘normal’ family that is the basis for the promise of redemption of the offender” (Aungles & Cook, 1994, p. 78). However, this ideal can contradict some families’ socioeconomic conditions and relational dynamics.

In the case of electronic monitoring, it is, therefore, necessary to understand the extent to which families effectively have living conditions capable of ensuring compliance. As an example, I highlight the case of a Portuguese 36-year-old street vendor who, in 2018, had been sentenced to 7 months of house arrest but could not comply because his household did not have legalised electricity, a mandatory requirement for the electronic monitoring system. Consequently, he was imprisoned in a non-continuous detention regime (serving his sentence during weekends). That occurred even though the court recognised the precarious economic situation of the household. As highlighted by Maria João Antunes, one of the jurists who was involved in the creation of the law that allows prison sentences of less than 2 years to be served under an electronic monitoring regime, in statements to the Público newspaper, “this case confronts us with the obligations of the welfare State. The system has to evolve” (Henriques, 2018, para. 2).

In addition, how connections between family support and reintegration have been equated reveal a subtle, but still significant, tendency to shift some of the responsibilities of the penal system related to social reintegration to families (Touraut, 2012). As Helen Codd (2007) underlines:

to some extent, therefore, it follows that the government could “shift the blame”, deflecting issues of recidivism away from discussions of the failures of negative, disintegrative punitive practices, towards making it not only a failure of the individual offender but also a failure of his or her family. (pp. 259-260)

In other words, both in social reintegration processes and in the context of electronic monitoring measures, the family becomes the target of a series of expectations that end up co-opting it into the criminal sphere. This orientation reflects broader trends characteristic of neoliberal regimes (Harvey, 2005), gaining prominence and shifting responsibility away from the State and other institutions towards individuals, underlining how rehabilitation has become a matter of individual responsibility (Bosworth, 2007).

Besides the co-optation of family in the penal sphere, electronic monitoring also highlights the transmutation of the domestic space into a place of confinement. Such symbolic redefinition of the house, other than involving changes in daily family routines (such as rearranging schedules and activities), implies that family members become active agents in surveillance processes, in the process of “participatory monitoring” (Staples, 2014) that involves not only the individuals under monitoring but also their relatives (Staples, 2005). As William Staples (2005) underlines through his investigation of the implications of electronic monitoring in the USA context:

through their efforts at “supporting” those on house arrest, intimates become caught up in the role of ancillary “watchers” for the program, creating a kind of collusion between the family goal of getting the offender off house arrest and the official goal of ensuring program compliance. (p. 157)

This transmutation of the domestic space into a penal space was also recognised by the minister of justice, Francisca Van Dunem, when, in November 2018, she published an opinion article in the Público newspaper, reflecting upon electronic monitoring:

in a search for alternative solutions capable of ensuring the effectiveness of criminal measures, the 2017 legislator ended up reinforcing, in the Portuguese sanctioning system, the use of a new punitive instrument whose potentialities allow to move the punitive space from the traditional prison environment to a diverse space, such as the convict’s residence, under electronic monitoring. (Van Dunem, 2018, para. 8)

In short, by being portrayed as one of the most critical agents in the reintegration processes (Naser & Vigne, 2006; Vigne et al., 2004), families and the domestic space ultimately co-integrate supervision and control processes. The use of electronic monitoring thus ends up expanding the “collective dimension” (Granja, 2018; Touraut, 2009, 2012) of punishment, discipline, and control that these types of criminal sanctions entail (Staples, 2005, p. 140).

5.3. Narrowing the Debate on Domestic Violence

Among all the penalties and measures covered by the electronic monitoring system in Portugal, the prohibition of contacts between offenders and victims of domestic violence (controlled by geolocation) is currently the most expressive (representing in 2020 around 54%; Direção-Geral da Política de Justiça, n.d.). However, the complex ways in which electronic monitoring can work both for and against victims of domestic violence have been largely overlooked. As explained in 2013, by the then director of the electronic monitoring system, Nuno Caiado, in the context of a parliamentary hearing on electronic monitoring for perpetrators of domestic violence, the system of radiofrequency implies an evident involvement of the victim:

it is necessary to understand the type of collaboration the victim can provide when involved in electronic monitoring operations. In reality, the victim will always have an equally active role. The victim is not passive. When subject to electronic monitoring, the victim, because he/she is also subject to electronic monitoring operations, will have an active role and will have to be as cooperative as ( ... ) the offender in electronic monitoring operations. (Assembleia da República, 2013, 26:27)

If the active role of the victim is a sine qua non condition for the success of this electronic monitoring regime, it is, therefore, necessary to consider the complex ways in which electronic monitoring can work both for and against victims of domestic violence. When this system is promoted as a tool that guarantees security and justice, within an imaginary of techno-optimism fed by public institutions and the media, it becomes difficult to assess to what extent it may fail its promise. Likewise, it is also complex to analyse the extent to which electronic monitoring of victims can contribute to narratives that contribute to blaming victims in judicial contexts. Those responsible for the Directorate-General for Reinsertion and Prison Services express an example in their statements. Following the murder of a domestic violence victim, such statements were widely disseminated by the media under the electronic monitoring geolocation system in 2017. After the murder, several news headlines highlighted the need for victims to wear the protection unit device at all times:

Authorities warn victims of domestic violence. They should always use monitoring devices. Warning arrives after a couple has been found dead inside a car. He had an electronic bracelet and the woman a device that warned the authorities if the aggressor approached, but she did not take the device to the meeting (TVI 24). (Autoridades Deixam Alerta a Vítimas de Violência Doméstica, 2017, para. 1)

According to the Directorate-General, although they are not “judicially” obliged to use such equipment, victims of domestic violence must do so for “personal protection”, which “did not happen” to the woman who was found dead on Wednesday inside a car in Vila Nova de Gaia. ( ... ) In an interview with Lusa, João Moreira, Director of Organization, Planning and External Relations Services at the Directorate-General for Reinsertion and Prison Services, pointed out that no victim of domestic violence is obliged by justice to use the Victim Protection Unit (VPU) device, but should do it for the “preservation of life”. “Although there is no legal obligation to force the victim to use the device, the victim must carry the device”, reiterated João Moreira, admitting that the case of the woman who turned up dead last Wednesday inside a car could have had another outcome if she had the device with her. (Lusa, 2017, paras. 2-10)

Therefore, it is clear how a system designed to protect victims ends up making them co-responsible for their safety and, ultimately, for the preservation of their own lives. Considering the high complexity of situations of domestic violence (Casimiro, 2002; Dias, 2010) as well as victims’ low trust in the criminal justice system, there is an urgent need to re-imagine prevention efforts that do not rely solely on monitoring technologies that hold victims accountable for their safety. Understanding how techno-optimism about electronic monitoring is produced and maintained opens the possibility of recognising and questioning the consequences of that optimism for victims of domestic violence and stalking and their communities. Techno-optimism restricts collective criticism and opposition to the potential negative consequences of electronic monitoring on victims and undermines collective capacities to imagine alternative solutions to domestic violence (Quinlan, 2020; Morozov, 2013). More broadly, techno-optimism also narrows public dialogue about preventing violence rather than promoting debates about the social and cultural roots of violence and the reform of the criminal justice system.

6. Conclusion

Returning to the brief interaction with a prisoner who had been under electronic monitoring that I mentioned at the beginning of this article, I now understand that the techno-optimism that has been marking the dominant discourse on electronic monitoring also influenced my reaction, as well as and more importantly, obliterates collective criticism of the invisible implications of electronic monitoring. Although electronic monitoring can effectively reduce the prison population, facilitate the maintenance of social ties, and protect victims of domestic violence, within the scope of this article, I attempted to analyse how these effects can coexist with other implications that tend to be made invisible by the techno-optimism that frames this penal instrument in Portugal. More particularly, how this techno-optimism restricts a critical perspective on how electronic monitoring expands the penal network, co-opts the family in the penal sphere and transmutes the domestic space into a space of confinement, as well as narrows the debate on domestic violence, contributing, even if unintentionally, for the co-responsibilisation of victims.

Imbued in discourses disseminated not only by official institutions but also by the media and by an effervescent surveillance industry, the techno-optimism surrounding electronic monitoring, therefore, ends up restricting public debates on the reform of the criminal justice and the penal system to the domain of technoscience, rather than opening dialogues about the social and cultural roots of these phenomena (see also Quinlan, 2020). According to Ruha Benjamin (2019), an author who reflects on how racism and social inequalities are embedded in artefacts and technological mechanisms in a socially invisible way, electronic monitoring is, therefore, an example of “technological benevolence”. In other words, a technology legitimised by managerialism and economist arguments that aim to solve complex social and penal problems without looking deeply at their systemic roots, impossible to solve only with technological artefacts.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programmatic funding) and by the contracts with the references CEECIND/00984/2018 and CEECINST/00157/2018 (attributed to Rafaela Granja).

REFERENCES

Amelung, N., Granja, R., & Machado, H. (2020). Modes of bio-bordering: The hidden (dis)integration of Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Assembleia da República. (2013, 28 de novembro). Audição parlamentar Nº 21-SCI-XII. https://www.parlamento.pt/ActividadeParlamentar/Paginas/DetalheAudicao.aspx?BID=96400 [ Links ]

Assembleia da República. (2020, 14 de julho). Diretor-geral de reinserção e serviços prisionais na subcomissão para a reinserção social e assuntos prisionais. https://www.parlamento.pt/Paginas/2020/julho/Diretor-Geral-Reinsercao-Servicos-Prisionais-na-Subcomissao-Reinsercao-Social-Assuntos-Prisionais.aspx [ Links ]

Aungles, A., & Cook, D. (1994). Information technology and the family: Electronic surveillance and home imprisonment. Information Technology & People, 7(1), 69-80. https://doi.org/10.1108/09593849410074034 [ Links ]

Autoridades deixam alerta a vítimas de violência doméstica. (2017, 2 de novembro). TVI24. https://tvi24.iol.pt/sociedade/pulseira-eletronica/autoridades-alertam-vitimas-de-violencia-domestica-devem-usar-sempre-dispositivo-de-vigilancia [ Links ]

Baiona, C., & Jongelen, I. (2010). “Prisão sem grades”: Factores para o sucesso da medida. Ousar Integrar: Revista de Reinserção Social e Prova, 6, 61-72. [ Links ]

Baumer, E. P., O’Donnell, I., & Hughes, N. (2009). The porous prison: A note on the rehabilitative potential of visits home. The Prison Journal, 89(1), 119-126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885508330430 [ Links ]

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Berg, M. T., & Huebner, B. M. (2011). Reentry and the ties that bind: An examination of social ties, employment, and recidivism. Justice Quarterly, 28(2), 382-410. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2010.498383 [ Links ]

Beyens, K. (2017). Electronic monitoring and supervision: A comparative perspective. European Journal of Probation, 9(1), 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2066220317704130. [ Links ]

Bosworth, M. (2007). Creating the responsible prisoner: Federal admission and orientation packs. Punishment & Society, 9(1), 67-85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474507070553 [ Links ]

Caiado, N. (2014). Pre-trial electronic monitoring in Portugal. Criminal Justice Matters, 95(1), 10-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09627251.2014.902197 [ Links ]

Casimiro, C. (2002). Representações sociais de violência conjugal. Análise Social, XXXVII(163), 603-630. http://analisesocial.ics.ul.pt/documentos/1218733193N7lLR3rn1Yd68RN0.pdf [ Links ]

Codd, H. (2007). Prisoners’ families and resettlement: A critical analysis. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 46(3), 255-263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2311.2007.00472.x. [ Links ]

Cohen, S. (1985). Visions of social control: Crime, punishment and classification. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Cunha, M. I. (2008). Disciplina, controlo, segurança: No rasto contemporâneo de Foucault. In C. Fróis. (Ed.), A sociedade vigilante: Ensaios sobre vigilância, privacidade e anonimato (pp. 67-81). Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Dardot, P., & Laval, C. (2016). A nova razão do mundo: Ensaios sobre a sociedade neoliberal. Boitempo. [ Links ]

Dias, I. (2010). Violência doméstica e justiça: Respostas e desafios. Sociologia: Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, XX, 245-262. [ Links ]

Direção-Geral da Política de Justiça. (s.d.). Reinserção social. Estatísticas da Justiça. Retirado a 9 de novembro, 2021, de https://estatisticas.justica.gov.pt/sites/siej/pt-pt/Paginas/ReinsercaoSocial.aspx [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (s.d.-a). Um instrumento para controlo dos agressores de violência doméstica e um contributo para melhor proteção das vítimas. Ministério da Justiça, República Portuguesa. https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Portals/16/Justica%20Adultos/Vigil%C3%A2ncia%20eletr%C3%B3nica/Informacao%20Espec%C3%ADfica/VE_VD%20%20FOLHETO%202018.pdf?ver=2018-11-26-165429-673 [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (s.d.-b). Relatório de atividades e autoavaliação atividades 2018. Ministério da Justiça. https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Portals/16/Instrumentos%20de%20Planeamento%20e%20Gest%C3%A3o/Relat%C3%B3rio%20de%20atividades/2018/RA_2018.pdf?ver=2019-07-11-154949-080 [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (s.d.-c). Relatório de atividades e autoavaliação atividades 2019. Ministério da Justiça. https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Portals/16/Instrumentos%20de%20Planeamento%20e%20Gest%C3%A3o/Relat%C3%B3rio%20de%20atividades/2019/RA-2019.pdf?ver=2020-09-22-170956-227 [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (s.d.-d). Vantagens. Retirado a 15 de junho, 2021, de https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Justi%C3%A7a-de-adultos/Vigil%C3%A2ncia-eletr%C3%B3nica/Vantagens [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (s.d.-e). Vigilância eletrónica. Retirado a 15 de junho, 2021, de https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Estat%C3%ADsticas-e-indicadores/Vigil%C3%A2ncia-Eletr%C3%B3nica [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (s.d.-f). Vigilância Eletrónica. Breve enquadramento histórico. Retirado a 15 de junho, 2021, de https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Justi%C3%A7a-de-adultos/Vigil%C3%A2ncia-eletr%C3%B3nica/Breve-enquadramento-hist%C3%B3rico [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (2020, 22 de julho). Reinserção social e vigilância eletrónica com novas instalações. Justiça.gov.pt. https://justica.gov.pt/Noticias/Reinsercao-Social-e-Vigilancia-Eletronica-com-novas-instalacoes [ Links ]

Direção-Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais. (2021, 5 de março). Número de casos em vigilância eletrónica cresce face a 2020. Justiça.gov.pt. https://justica.gov.pt/Noticias/Numero-de-casos-em-vigilancia-eletronica-cresce-face-a-2020 [ Links ]

Dünkel, F., Thiele, C., & Treig, J. (2017). “You’ll never stand-alone”: Electronic monitoring in Germany. European Journal of Probation, 9(1), 28-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/2066220317697657 [ Links ]

Duwe, G., & Clark, V. (2011). Blessed be the social tie that binds: The effects of prison visitation on offender recidivism. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 24(3), 271-296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403411429724 [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Frois, C. (2013). Peripheral vision: Politics, technology, and surveillance. Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Frois, C. (2015). Dos estudos de vigilância, videovigilância e tecnologia. Reflexão sobre o estado da arte. In M. I. Cunha (Eds.), Do crime e do castigo: Temas e debates contemporâneos (pp. 147-157). Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

Frois, C. (2020). Prisões. Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. [ Links ]

Frois, C., & Machado, H. (2016). Modernization and development as a motor of polity and policing. In B. Bradford, B. Jauregui, I. Loader, & J. Steinberg. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of global policing (pp. 391-405). Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Fuchs, C. (2011). Como podemos definir vigilância? Matrizes, 5(1), 109-136. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1982-8160.v5i1p109-136 [ Links ]

Granja, R. (2018). Sharing imprisonment: Experiences of prisoners and family members in Portugal. In R. Condry & P. S. Smith (Eds.), Prisons, punishment, and the family: Towards a new sociology of punishment? (pp. 258-272). Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Henriques, A. (2018, 23 de novembro). Foi para a cadeia por não ter electricidade para pulseira. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2018/11/23/sociedade/noticia/feirante-carta-cadeia-falta-electricidade-casa-1852100 [ Links ]

Hucklesby, A., Beyens, K., & Boone, M. (2021). Comparing electronic monitoring regimes: Length, breadth, depth and weight equals tightness. Punishment and Society, 23(1), 88-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474520915753 [ Links ]

Jasanoff, S. (Ed.). (2004). States of knowledge. The co-production of science and social order. Routledge. [ Links ]

Jasanoff, S., & Kim, S.-H. (2009). Containing the atom: Sociotechnical imaginaries and nuclear power in the United States and South Korea. Minerva, 47(2), 119-146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-009-9124-4 [ Links ]

Jasanoff, S., & Kim, S.-H. (2015). Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. University of California Press. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (1987). Science in action. How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (2000). When things strike back: A possible contribution of “science studies” to the social sciences. The British Journal of Sociology, 1(51), 107-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2000.00107.x [ Links ]

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts. Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Laurie, E., & Maglione, G. (2020). The electronic monitoring of offenders in context: From policy to political logics. Critical Criminology, 28(4), 685-702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-019-09471-7 [ Links ]

Law, J. (2008). On sociology and STS. Sociological Review, 56(4), 62-649. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2008.00808.x [ Links ]

Lei n.º 33/2010, Diário da República n.º 171/2010, Série I de 2010-09-02, 3851 - 3856 (2010). https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/33-2010-344262 [ Links ]

Lei n.º 94/2017, Diário da República n.º 162/2017, Série I de 2017-08-23, 4915 - 4921 (2017). https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/94-2017-108038373 [ Links ]

Lopes, N., & Oliveira, C. S. (2016). Vigiando a violência: O uso de meios de controlo e fiscalização à distância em processos de violência doméstica. Gênero & Direito, 5(1), 68-91. https://doi.org/10.18351/2179-7137/ged.v5n1p68-91 [ Links ]

Lusa. (2017, 2 de novembro). Vítimas de violência doméstica devem usar sempre dispositivo de alerta - autoridades. Diário de Notícias. https://www.dn.pt/lusa/vitimas-de-violencia-domestica-devem-usar-sempre-dispositivo-de-alerta---autoridades-8890092.html [ Links ]

Lynch, M. (2012). Science and technology studies: Critical concepts in the social sciences. Routledge. [ Links ]

Lyon, D. (2002). Surveillance as social sorting. Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Lyon, D. (2003). Surveillance after September 11. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Lyon, D. (2018). Cultura da vigilância: Envolvimento, exposição e ética na modernidade digital. In B. Cardoso & L. Melgaço (Eds.), Tecnopolíticas da vigilância: Perspectivas da margem (pp. 151-179). Boitempo. [ Links ]

Machado, H., & Frois, C. (2014). Aspiring to modernization: Historical evolution and current trends of state surveillance in Portugal. In K. Boersmaet, R. v. Brakel, C. Fonio, & P. Wagenaar (Eds.), Histories of state surveillance in Europe and beyond (pp. 65-78). Routledge. [ Links ]

Mallart, F. (2019). O arquipélago. Tempo Social, 31(3), 59-79. https://doi.org/10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2019.161327 [ Links ]

Mallart, F., & Cunha, M. I. (2019). Introdução: As dobras entre o dentro e o fora. Tempo Social, 31(3), 7-15. https://doi.org/10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2019.162973. [ Links ]

Martins, N. M. F. (2019). Ciberjustiça - A ética na vigilância eletrónica em Portugal. ReseachGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348362918_Ciberjustica_-_A_Etica_na_Vigilancia_Eletronica_em_Portugal [ Links ]

Marx, G. T. (2002). What’s new about the “new surveillance”? Classifying for change and continuity. Surveillance & Society, 1(1), 9-29. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v1i1.3391 [ Links ]

Matthews, R. (2013). Rethinking penal policy: Towards a systems approach. In R. Mattehws & J. Young (Eds.), The new politics of crime and punishment (pp. 223-249). Willan. [ Links ]

McNeill, F., & Beyens, K. (2013). Introduction: Studying mass supervision. In F. McNeill & K. Beyens (Eds.), Offender supervision in Europe (pp. 1-18). Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Mills, A., & Codd, H. (2008). Prisoners’ families and offender management: Mobilizing social capital. Probation Journal, 55(1), 9-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264550507085675. [ Links ]

Mirowski, P. (2019). Hell is truth seen too late. Boundary 2, 46(1), 1-53. https://doi.org/10.1215/01903659-7271327 [ Links ]

Morais, R. (2014). Os dispositivos disciplinares e a norma disciplinar em Foucault. Ítaca, 27, 185-217. https://revistas.ufrj.br/index.php/Itaca/article/view/2439 [ Links ]

Morozov, E. (2013). To save everything, click here: The folly of technological solutionism. PublicAffairs. [ Links ]

Naser, R. L., & Vigne, N. G. La (2006). Family support in the prisoner reentry process: Expectations and realities. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 43(1), 93-106. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v43n01_05 [ Links ]

Nellis, M., Beyens, K., & Kaminski, A. D. (Eds.). (2013). Electronically monitored punishment: International and critical perspectives. Routledge. [ Links ]

Pimentel, I. (2007). A história da PIDE. Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

PORDATA. (2021, 9 de novembro). Ocupação efectiva das prisões (%). https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Ocupa%c3%a7%c3%a3o+efectiva+das+pris%c3%b5es+(percentagem)-635 [ Links ]

Quinlan, A. (2020). The rape kit’s promise: Techno-optimism in the fight against the backlog. Science as Culture, 30(3), 440-464. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2020.1846696 [ Links ]

Ribeiro, M. (1995). A polícia política no Estado Novo, 1926-1974. Editorial Estampa. [ Links ]

Staples, W. G. (2005). The everyday world of house arrest: collateral consequencs for families and others. In C. Mele & T. A. Miller (Eds.), Civil penalities, social consequences (pp. 139-159). Routledge. [ Links ]

Staples, W. G. (2014). Everyday surveillance: Vigilance and visibility in postmodern life. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Sykes, G. M. (1958). The society of captives: A study in a maximum security prison. Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Touraut, C. (2009). Entre détenu figé et proches en mouvement. “L’expérience carcérale élargie”: Une épreuve de mobilité. Recherches familiales, 1(6), 81-88. https://www.cairn.info/journal-recherches-familiales-2009-1-page-81.htm [ Links ]

Touraut, C. (2012). La famille à l’épreuve de la prison. Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Trigueirão, S. (2019, 19 de outubro). Pulseiras electrónicas pouparam ao estado mais de 13,8 milhões de euros em três anos. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2019/10/19/sociedade/noticia/pulseiras-electronicas-pouparam-estado-138-milhoes-euros-tres-anos-1889463 [ Links ]

Van Dunem, F. (2018, 21 de novembro). O regime de permanência na habitação e a política criminal do XXI Governo Constitucional. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2018/11/21/sociedade/opiniao/regime-permanencia-habitacao-politica-criminal-xxi-governo-constitucional-1851791 [ Links ]

Visher, C. A., & Travis, J. (2003). Transitions from prison to community: Understanding individual pathways. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 89-113. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.095931 [ Links ]

Wacquant, L. (2000). As prisões da miséria. Celta Editora. [ Links ]

World Prison Brief, Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research. (s.d.). Highest to lowest - Prison population rate. World Prison Brief. Retirado a 28 de junho, 2021, de https://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison_population_rate?field_region_taxonomy_tid=14 [ Links ]

Received: June 28, 2021; Accepted: September 22, 2021

texto en

texto en