Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Comunicação e Sociedade

versão impressa ISSN 1645-2089versão On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.42 Braga dez. 2022 Epub 25-Fev-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.42(2022).3988

Thematic Articles

Social Media in Juvenile Delinquency Practices: Uses and Unlawful Acts Recorded in Youth Justice in Portugal

iCentro Interdisciplinar de Ciências Sociais, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

Na atualidade, o forte envolvimento dos jovens em redes sociais suscita o questionamento sobre potenciais efeitos multiplicadores de riscos e oportunidades para práticas de delinquência. Nem sempre é simples distinguir uma ação online inofensiva, parte integrante da experimentação social/relacional típica da adolescência, de um facto que passa a constituir um ilícito passível de intervenção judicial. Este artigo procura conhecer e discutir como o uso de redes sociais se materializa nos factos qualificados pela lei penal como crime praticados por jovens, entre os 12 e os 16 anos, no quadro da justiça juvenil em Portugal. Recorre-se à análise exploratória de informação qualitativa recolhida em Tribunal de Família e Menores, nos processos tutelares educativos de 201 jovens, de ambos os sexos. Pouco mais de terço da população viu provado o envolvimento em ilícitos com recurso a redes sociais, em três níveis diferenciados: planeamento/organização, execução e disseminação. A participação múltipla em redes sociais é dominante. É significativa a sobrerrepresentação das raparigas enquanto autoras de ilícitos, especialmente com elevado grau de violência, num continuum online-offline. A maioria dos factos analisados, de ambos os sexos, tem no epicentro, a perceção de que a honra pessoal foi atingida e requer reparação. Daí ao ato violento é um passo curto, o que pode levar à reconfiguração e troca de papéis entre vítima e agressor, nem sempre fácil de provar. Para ambos os sexos, as relações criadas a partir da escola dominam a interação entre agressores-vítimas. Mais do que o anonimato que o digital pode proporcionar, transparece a necessidade de afirmação no espaço público e/ou semiprivado, constituindo a ação violenta o catalisador para ganhar respeito pela imediata gratificação, que as redes sociais oferecem, num continuum online-offline que dá corpo à “onlife” (Floridi, 2017) que caracteriza a vida dos jovens no presente.

Palavras-chave: jovens; redes sociais; práticas digitais; delinquência; justiça juvenil

Currently, the strong involvement of young people in social media raises questions about potential multiplier effects on risks and opportunities for delinquent practices. It is not always easy to distinguish a harmless online action, an integral part of the social and relational experimentation typical of adolescence, from a fact that will constitute an unlawful act subject to judicial intervention. This article seeks to understand and discuss how the use of social media is materialized in the facts, defined as a crime by the criminal law, perpetrated by young people aged between 12 and 16, in the context of youth justice in Portugal. It is based on an exploratory analysis of qualitative information collected in a Family and Children Court from youth justice proceedings concerning 201 young people of both sexes. Just under a third of this population was proven to have been involved in unlawful acts using social media at three levels: planning/ organization, execution and dissemination. Multiple participation in social media is dominant. There is a significant overrepresentation of girls as perpetrators of unlawful acts, especially those involving a high degree of violence, embodying the online-offline continuum. Most of the analysed facts of both sexes have at their epicentre the perception that personal honour has been attacked and requires reparation. From there, it is a short step to violence, which can lead to a reconfiguration and exchange of roles between victim and aggressor, which is not always easy to prove. For both sexes, the relationships established in school dominate the interaction between aggressors-victims. More than the anonymity afforded by the digital, what stands out is the need for affirmation in public and/or semi-private space, and violent action is the catalyst to gain respect through the instant gratification offered by social media in an online-offline continuum embodying the “onlife” (Floridi, 2017) that characterizes the lives of young people today.

Keywords: young people; social media; digital practices; delinquency; youth justice

1. Introduction

As a result of the growing digitalization of society (Wall, 2007), youth justice is faced with new and complex challenges associated with the increasing use of digital technologies in delinquent practices in childhood and youth (M. Carvalho, 2019, 2021; Goldsmith & Wall, 2019; Rovken et al., 2018). The easy access to the internet, in any place and at any time, combined with the power it gives its users, shapes the lives of children and young people. Communication, learning, access to information, entertainment and participation are the main activities carried out online (Livingstone & Stoilova, 2019; Mascheroni et al., 2020). However, the internet also presents opportunities for offending (Baldry et al., 2018; McCuddy, 2021; Mojares et al., 2015). Those can take the form of traditional types of crime (i.e., threat, insult, defamation, fraud, extortion, breach of trust and pornography, among others) now perpetrated using technological equipment and applications. On the other hand, it can correspond to new types of crime (i.e., hacking and denial of service attacks [DDoS], among others) that depend exclusively on the use of digital technologies (Wall, 2007).

Currently, social network sites - web-based services that allow users to establish contact with each other by creating a public or semi-public personal profile (boyd & Ellison, 2008) - are a key component of youth socialization and culture (B. Carvalho & Marôpo, 2020; Vilela, 2019). Ease of access, speed and a broad public reach characterize these forms of social participation mediated by the internet. Young people draw several benefits from using social media as an audience or content creators (B. Carvalho & Marôpo, 2020; Ponte et al., 2022). Nevertheless, certain actions represent the perpetration of unlawful acts, often without the young people directly involved, or their family members/caretakers, realizing that they are committing an act defined as a crime by the criminal law. The existing literature highlights that digital practices are neither exclusively positive nor exclusively negative (Staksrud, 2009); such an assessment will depend on the social actors involved and on a host of different factors, including the degree of compliance with the law (Baldry et al., 2018; McCuddy, 2021).

The study presented in this article is part of the project Youth Offending in the Juvenile and Criminal Justice Systems in Portugal (YO&JUST), supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Funding Agency for Science And Research; SFRH/116119/2016). It aims to explore and discuss how the use of social media is materialized in the facts defined as a crime by the criminal law perpetrated by young people aged between 12 and 16 in the context of youth justice in Portugal.

In a field where knowledge is scarce, this exploratory analysis of the information collected from educational guardianship proceedings seeks to identify and debate the facts and associated dynamics involving the actions of young people on social media for which measures were imposed by a Family and Children Court. By incorporating into the discussion input from sociology, communication sciences and psychology, a unique portrait is drawn to contribute to the advancement of knowledge on how technological development impacts juvenile delinquency as recorded by the mechanisms of formal social control. Scientific evidence is put forth to promote a better understanding of the implications of the involvement of young people in social media and thereby support more informed debate on the regulation and criminalization of digital practices as a key element for the creation of delinquency prevention policies (Goldsmith & Wall, 2019; Patton et al., 2014).

2. Young People and Social Media

In societies marked by risk aversion (Livingstone & Stoilova, 2019), the strong involvement of young people in social media (i.e., Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, Telegram, WeChat, YouTube and TikTok, among others) raises questions about potential multiplier effects on risks and opportunities for delinquent practices. Sexting, cyberbullying, sextortion, flaming, happy slapping and cyberstalking have become everyday terms3, and they describe unlawful actions in digital environments whose perpetrators and victims are often young people. The media coverage of these cases is viral, taking place on a global scale, and social concern over this issue is rising (Baldry et al., 2018).

In Western societies, the transformations experienced by the instances of informal social control (i.e., family, school) are countered by the widening expectations of communities regarding the mechanisms of formal social control, such as the courts, from which individuals and social groups demand stronger regulation of young people’s behaviour (M. Carvalho, 2019). In some countries, this leads to increased punitive trends as a reaction to juvenile delinquency (Goldsmith & Wall, 2019; Rovken et al., 2018).

The children and young people of today have never known a world without the internet; they are increasingly online at younger ages and make greater use of personal mobile devices, in a dual role as digital content creators and consumers (Mascheroni et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2020). Against this backdrop, social media are central to the everyday life of children and young people, offering endless opportunities for social dynamics that unfold across various places simultaneously as a result of the offline-online enabled by the internet (Livingstone & Stoivola, 2019). In societies marked by profound technological advancements, which reconfigure social dynamics and consumer cultures (B. Carvalho & Marôpo, 2020), social relations expand into webs of multiple actors and points of connection, breaking geographical barriers (Mojares et al., 2015). In this context, other questions arise:

teens don’t use social media just for the social connections and networks. It goes deeper. Social-media platforms are among our only chances to create and shape our sense of self. Social media makes us feel seen. ( … ) It’s true that social media’s constant stream of idealized images takes its toll: on our mental health, our self-image, and our social lives. After all, our relationships to technology are multidimensional-they validate us just as much as they make us feel insecure. ( … ) Perhaps social-media selfies aren’t the fullest representations of ourselves. But we’re trying to create an integrated identity. We’re striving not only to be seen, but to see with our own eyes. (Fang, 2019, paras. 5-6, 15)

Young people go through adolescence in the process of self-discovery, trying to understand their social roles, driven by a concern over how they pop up to others and are viewed by them in the context of ever-more complex emotional and social lives (Stern, 2008). The discovery of sexuality and intimate relationships is a central aspect of their digital practices, rooted in a constant reaffirmation of the “I” within the intricate relationships with the other(s) (Livingstone & Mason, 2015). There is a transformation of intimacy, which easily turns into a show based on narratives where the constant interplay between privacy and visibility, instantaneousness and personality cult, fiction and loneliness is omnipresent (Sibilia, 2008) and not exempt from various risks.

They can also become a threat and create health risks when they cross the line between real and virtual, public and private, between what is legal and what is illegal, “pirated”, between information and exploitation, between intimacy and distortion of “real” facts and images. (Eisenstein, 2013, p. 61)

In social media, young people constantly negotiate the boundaries of the public and private spheres of their lives and decide how they want to present and reveal themselves to other users (Stern, 2008). Sometimes they do so unexpectedly or suddenly, with a quick click of the mouse, without formulating an argument or fully anticipating the consequences. Other times, they do so under the veil of anonymity afforded by the digital. While access to social media is limited based on age, some circumvent this limitation by creating fake profiles, exposing themselves to greater risks (Vilela, 2019). In settings marked by an informational and technological literacy gap between generations, parents tend to underestimate their children’s involvement in online risky and aggressive behaviour and their experiences of harm (Baldry et al., 2018; McCuddy, 2021).

The time that young people spend on social media can be a way of reclaiming a private space they could not find elsewhere (Vilela, 2019). For most, social media are a means of social inclusion, and the fear of missing out and being excluded is real, even when the relationships they establish are only superficial.

Mutual insults, threats, sharing of nudes and unauthorized access to profiles are common occurrences on social media and are not exclusive to the younger generations. Young people can be influenced by modelling based on their observation of others, a phenomenon also known as contagion, but they can also act in response to challenges, often without knowing their source. The continuation of the transgressive behaviour will depend on the external reinforcement and whether (or not) it matches the young person’s expectation as well as on the nature of the forms of mediation (i.e., family, peers, others) that he or she is surrounded by (M. Carvalho, 2019).

In this regard, it is important not to minimize the growing visibility and influence of juvenile criminal groups/gangs that use social media to gain reputation and status by disseminating videos, messages and photos of their actions, to lure/recruit new members and/or to confront and challenge rivals (Haut, 2014; Oliveira & Carvalho, 2022; Storrod & Densley, 2017). Social media play an instrumental role in the dynamics of delinquency.

It is not always easy to distinguish a harmless action, an integral part of the social and relational experimentation typical of adolescence, from a fact that will constitute an unlawful act subject to judicial intervention. The subjectivities constructed by victims, aggressors and other participants are crucial for the discovery and subsequent proof of the facts. The overlap between the roles of victim and aggressor is a complex reality with a significant presence: the online “teen aggressor” tends to be, often, also the online “teen victim” (Ponte et al., 2021). The socio-digital construction of violence, easily accessible from anywhere in the world, now reaches social groups/audiences unaffected by the previous models of violence and impacts juvenile delinquency practices (M. Carvalho, 2019).

3. Connected Within the Network(s)

The use of social media by children and young people has increased in Portugal in the past few years (Matos & Equipa Aventura Social, 2018; Ponte et al., 2022), particularly among the youngest, at ages below the minimum threshold indicated for using different media (13 years; Ponte & Baptista, 2019). Compared to other countries, young people from Portugal are among those who use them the most - YouTube, WhatsApp and Instagram being the most prevalent (B. Carvalho & Marôpo, 2020; Matos & Equipa Aventura Social, 2018) - and also among those who make a more positive assessment of their digital skills (Ponte et al., 2022).

The study EU Kids Online (Ponte & Baptista, 2019) reveals that, in Portugal, the smartphone is the main medium used by children/young people (9-17 years) to access the internet on a daily basis, predominantly for social media use (75%), communication (75%) and entertainment, such as listening to music/watching videos (80%). The use of the internet starts earlier. Girls display higher levels of engagement in social media, communication with friends and family and listening to music; they own a smartphone more often (albeit at older ages than boys) and have greater access to the internet outside the house (i.e., at school and en route). Boys look more frequently for groups with shared interests/hobbies, news and video games.

As the age increases, so does the use of social media. The main motivation for this use is access to a group of peers, with only a small percentage of the respondents not being allowed to use them: 7% (boys: 18%; girls: 11%; Ponte & Baptista, 2019).

About a quarter of the population in this research (23%) had experienced, in the previous year, online situations that had bothered/upset them, pointing out instances of undesired and/or aggressive contact on social media (Ponte & Baptista, 2019). Bullying (24%) was among the most frequently mentioned situations, with cyberbullying being predominant compared to face-to-face bullying. Exposure to pornography (37%) and sexting (1 out of 4 at ages 11-17, 29% of the girls and 44% of the boys) are particularly relevant. About a third of the boys (30%) and 7% of the girls had received messages of sexual nature by text, image or video. About half said they had been neither pleased nor upset, while 32% had been pleased. Images of a sexual nature are seen more frequently on the internet than television (Ponte & Baptista, 2019).

The data of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children in Portugal HBSC/PT-2018 (Matos & Equipa Aventura Social, 2018) regarding the role of social media in the everyday life of the young people who were surveyed are also relevant. The following are noteworthy: having tried to spend less time on them but not being able to do so (26%), feeling bad when unable to use them (20.9%), or frequently being unable to think of anything other than using them again (20%). About half of the respondents said they spent 2 hours or more daily on social media (Matos & Equipa Aventura Social, 2018).

Such is the portrait drawn from national works of research that reveal how central social media have become to young people’s lives.

4. Empirical Study

This study is part of the initial phase of data analysis under the YO&JUST project. It aims to explore and discuss how the use of social media is materialized in the facts defined as crimes by the criminal law perpetrated by young people aged between 12 and 16 and for which measures were imposed in the context of youth justice in Portugal (Lei n.º 4/2015, 2015).

Based on the qualitative information collected from the records of educational guardianship proceedings involving 201 young people (83% of the total) of both sexes and subject to a final decision in the jurisdictional phase, between 1 January 2015 and 30 June 2021, in a Family and Children Court, all proved facts containing a reference to the use of social media were identified and selected for thematic content analysis, organized into categories according to the types of crime involved. The data on the perpetrators (i.e., sex and age) were organized and codified in MS Excel and exported to a database created in IBM SPSS v.25, which will be used for future analyses.

Data collection for this study was carried out by the author in person, at the court, with prior authorization from the High Council for the Judiciary (2019/GAVPM/1436) and the judge responsible for the case. It took place between November 2019 and August 2021, with a 1-year interruption due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. All the information was anonymized, and the names of the young people were replaced with two randomly selected letters to protect the privacy of the participants mentioned in the procedural documents.

5. Results and Discussion

The focus of the analysis presented in this article is the use(s) of social media in the perpetration of unlawful acts as recorded in judicial proceedings. First, a sample description will be provided, followed by an exploration of the dynamics associated with the planning/organization, execution and dissemination of the unlawful act.

5.1 Facts Under Analysis

Out of a total of 354 facts proved in a court hearing during the period under analysis, 92 (26%)4 of the cases indicated the use of social media authored by 56 young people (27.8% of the total): 30 boys (50 facts, 54.3%) and 26 girls (42 facts, 45.7%). The difference between the sexes is slight and does not align with the trend regarding a lower representativity of females in offline delinquency recorded by the courts (M. Carvalho, 2019).

In terms of age at the time of the facts, 15-year-olds (n = 36, 20 boys) and 13-year-olds (n = 31, 16 boys) are more represented, followed by 14-year-olds (n =20, 10 boys), while the youngest (12-year-olds) have little representation (n = 5, 4 boys). In terms of age distribution, there is no significant difference between the sexes.

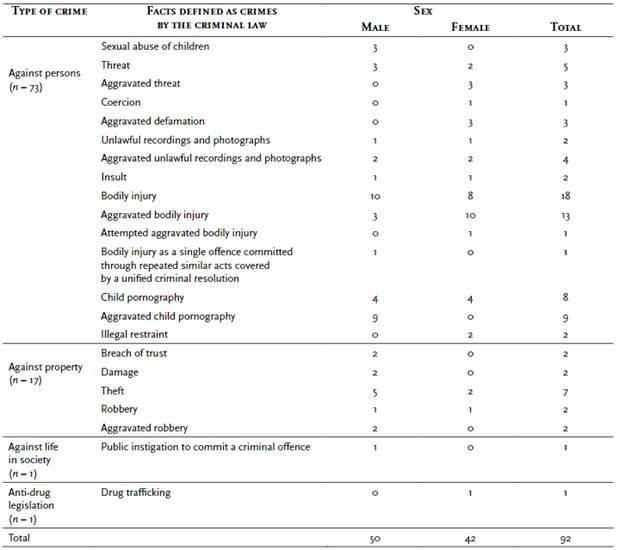

The instances of the use of social media are more expressive in the case of unlawful acts against persons (79.3%), especially when involving girls (Table 1). Significantly behind are the facts against property (18.4%), in which boys stand out. Facts against life in society related to narcotic drugs (trafficking) are residual.

It is possible to see a relationship between the use of social media and unlawful offline practices, especially in the case of bodily injury, which, across its different categories, amounts to more than a third of the total (35.8%), with girls being more represented than boys. Child pornography (18.5%), when “aggravated”, is exclusive to boys. Threats (8.7%), when “aggravated”, are exclusive to girls. By age, 15 and 13-year-olds are more represented in the category of facts against persons, while for 14-year-olds, in the category of the facts against property.

5.2 Planning and Organization

The planning/organization of unlawful acts through social media has a low representation in the proceedings analysed. However, when reported, it is associated with serious facts against persons and against property, especially aggravated bodily injury and aggravated robbery, that resulted in major personal damages.

The identification of closed groups on social media to prepare an assault on someone else joined intentionally and/or under pressure/threat from its users is relevant because of how the perpetration of violence is organized and, to a certain extent, normalized among young people (Mojares et al., 2015; Storrod & Desnley, 2017).

I was informed by the child TA [girl, 14 years old] of the existence of an organized group on Instagram with the address or group name #XXXXX#, where young females ask each other to commit acts of assault so that their names will not be connected with those acts, that is, some female children offer to assault others or are coerced into assaulting others to whom they are in no way related.

These practices are exclusively associated with girls in different contexts, revealing their increasing involvement in forms of violence traditionally seen as masculine, and thus could be a reflection of the construction of new forms of femininity (M. Carvalho et al., 2021).

Currently, meetings between young people organized through social media (meet) are an element of the youth cultures. Given the power of communication on the internet, they have the potential to quickly reach a high number of young people and different audiences. Meets are spaces of socialization that are becoming increasingly important for constructing social relationships and personal identity, experimentation and discovery, which are essential to the development during adolescence (Goldsmith & Wall, 2019; Stern, 2008).

Delinquent practices in a meet are the exception, and they do not represent the experience of most young people involved. However, the exploitation of some meets by rival groups of young people, mostly boys, frequently from territories in conflict, that come together to settle scores with each other is an occurrence that has been gaining visibility. That highlights the online-offline continuum (Donner et al., 2015) and how social media transform the nature of communication within a group and within the interaction with those who are perceived as “enemies”, with the meet serving as a tool to assert power through threats, intimidation and violence, but also to recruit new members (Haut, 2014).

LL [boy, 15 years old] went to the [local] MEET and found the boy victim who was part of a group of 10 individuals. LL knew a friend of the victim, and because of that, he went to meet them. LL was supposed to apologize to a friend of the victim. Since LL did not do so, the victim showed the tip of a knife and a glass bottle inside the backpack he was carrying. ( … ) Afterwards, things became peaceful, and when they were already outside, a group of boys came and said that LL and his friends could hit the victim. WL [boy, 15 years old] was hit on the head with the bottle, and LL kicked the victim in the belly because he had previously threatened him with a knife. He was not afraid of the victim, nor did he want the backpack. On that date, he was the subject of 4 pending educational guardianship proceedings. ( … ) The victim [boy, 17 years old] spent 9 days in the hospital for neurological monitoring.

The findings of this first level of analysis also include the actions of a 15-year-old girl on social media used as tools to strengthen drug trafficking networks. Easy to use and far-reaching when it comes to organized crime, social media guarantee anonymity under the veil of cryptography, with many of its users drawing a sense of impunity from the fact that activities are hard to trace (Haut, 2014; Oliveira & Carvalho, 2022), which calls for new approaches and means of criminal investigation in the context of youth justice.

5.3 Execution and Dissemination

For most children and young people, the distinction between online and offline makes no sense (Pereira et al., 2020; Ponte & Baptista, 2019). The ways of life of today’s children and young people embody the concept of “onlife” (Floridi, 2017), an everyday life marked by a continuous interweaving of physical and digital environments. This trend is evidenced by social media practices in the perpetration of unlawful acts, along two general lines: when they are committed on social media; and when they are the result of a prior interaction on those media, which is indicated as the reason for the facts.

New communication and social interaction patterns, including the ways of learning and expressing sexuality (Livingstone & Mason, 2015), are present in the proceedings analysed. In most cases, young people and their family members/caretakers are unaware that some practices constitute facts defined as a crime by criminal law.

AC [boy, 14 years old] asked VV [girl, 12 years old], via Messenger and/or WhatsApp, to send him photos of herself. She sent the first one in her bra and knickers ( … ) a total of 31 photos and one video with music where she can be seen dancing until she is naked. ( … ) AC sends the video via WhatsApp to TP [boy, 14 years old], who, in turn, sends it via WhatsApp to NA [boy, 14 years old]. NA sends it to BJ [boy, 13 years old] (who was VV’s boyfriend), and BJ sends it via Messenger to ZI, WR and QM [boys, 13-14 years old].

The victims’ unawareness of the sharing and lack of consent to it, the minimization of the harm caused and the need for reparation are common features of these actions. As the investigation and/or the taking of evidence in the hearing progresses, the complexity of the social reality is revealed, and, in some cases, a reconfiguration of the roles of victim and aggressor emerges. At a certain point, the victim becomes/became the aggressor, and the aggressor becomes/became the victim. This overlap between victimization and aggression, a characteristic of the paths of many young people (M. Carvalho, 2019), expands due to the speed with which it unfolds on the internet (Ponte et al., 2021).

Other dynamics reveal that young people bothered by the requests of their peers on social media end up not sending nudes of themselves in response; but, unwilling to admit to this refusal due to pressure, fear or another reason, end up exposing themselves even more by resorting to online pornography websites to search for images that they then send as their own.

KH [boy, 13 years old] was one of her best friends at the time. She recalls KH asking her to send intimate photographs of herself. Not wanting to send photographs of herself, she searched on Google for a photograph of that type and sent it. She regrets doing it, clarifying that she did not know that sending this kind of photograph to another person could be a crime and that had she known this at the time, she would not have done it [girl, 13 years old].

Not only does the suspect [boy, 14 years old] humiliate and harass the girl [12 years old] in person, but he also uses social media to do it, especially Facebook. He uses social media to send photographs of his genitals and to try to maintain a conversation of a sexual nature to lure her into performing the act with him. ( … ) The suspect tells the child to search for certain webpages allegedly of interest to her, sending her links to pornography sites and asking her to send him photos of “hot chicks”. The child said the suspect repeatedly asked her to take photographs of her vagina and send them to him, which she has always denied.

The link between internet searches and participation in the world of pornography often occurs as a result of apparently innocent and unanticipated encounters that can lead to the consumption and production of pornography, given the ease of anonymous access to search engines like Google (Goldsmith & Wall, 2019). Some young people realize, at an early age, that they can easily obtain material gains from the sexualized exploitation of contacts with adults, which they can easily establish on social media.

During the time they dated and until ( … ), SB [boy, 15 years old], under circumstances that could not be established, pointed a knife at CA [girl, 14 years old] and also punched and slapped her in the face, either out of jealousy - due to CA speaking to other boys - or because he wanted her to give him the money that her mother gave her for a meal, which she said she didn’t have, but he ended up finding out that she did. In [2 years before], knowing that this was possible, CA, who was 12 at the time, searched for websites and social media where, for a sum of money, she would kiss male individuals or perform acts of a sexual nature to them. To that effect, she established contact with someone who asked her if she wanted to ( … ) and told her that he would give her money according to the type of acts she was willing to undergo. For an unspecified period, on her own initiative, CA used her mobile phone to arrange encounters ( … ) with that man and other males, kissing them, being groped and consenting to take photographs half-naked, without SB knowing. For those activities, she was never paid less than 50 euros, which she gave him and which he spent “on neighbourhood business, with his partners”, or buying hashish (from his grandmother) and tobacco, which they both consumed.

This case highlights how within a framework of supposed autonomy - associated with the dissolution of social ties and with intimate relationships marked by an escalation of violence - “business” on social media can become a source of income.

Some of the proceedings show how easy it is for young people of both sexes to circumvent the minimum age limits established for the creation of pages/profiles on certain social media and how, when a page is blocked, they simply and immediately create another one under a different name/nickname. The modification of the date of birth is usually complemented by manipulating the profile photo using special effects and/or accessories to hide the real age.

FV [girl, 15 years old] is the girlfriend of PM [boy, 15 years old]. She clarified that she had a Facebook page ( … ) that Facebook itself cancelled/blocked this page. ( … ) On her old page, she indicated XX.XX.1996 as the date of birth, in which the day and month were correct, but the year was changed from 2003 to 1996, thus allowing her to portray a 20-year-old girl/woman when at the time of the facts she was only 13 years old. At the time, she told her mother she couldn’t understand why her page had been blocked and created a new page she currently uses. That the cancellation of her old page occurred on XX 2018, which she believes was when her boyfriend sent her a photograph with the exposed genitals of a girl. At the time of the facts, PM explained to her that the photograph mentioned above had been sent to him by a girl known by the name RT who, during the year 2015, had been a student at the ( … ) school where FV had studied ( … ). Before her boyfriend sent her this photo, RT herself had already sent it to her via Skype, saying that the photograph was hers, though she doesn’t know whether that is true. In the previous 3 or 4 days, she had spoken with RT herself on Instagram, telling her that she was no longer sure whether she had sent the photo via Skype or Facebook.

Since the discovery of sexuality is a developmental task of adolescence, these actions are, in most cases, described by young people as “it was all just a children’s game because, at the time the facts occurred, everyone was under 13 years old” (boy, 15 years old) or “without realizing that this fact could be associated with the crime of child pornography” (girl, 15 years old). Given the criminal nature of some of the images shared, the educational guardianship proceedings may stem from reports from supranational bodies, such as the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, within the framework of international cooperation to combat networks of sexual abuse of children and child pornography. These actions have various consequences, and in light of the extent to which criminal investigation authorities intervene in the contexts in which young people live, such is the case of the girl “that due to the facts reported, the house of her maternal grandmother was subject to a house search in connection with the crime of child pornography, as shown by the copy of the search warrant”.

Prior interactions on social media are common in the case of facts against persons carried out offline. Thus, there is a transposition into virtual environments of interactions that, before the internet existed, were confined to physical territories.

These three children [NE, VQ and KJ, boys, 13 years old], now with the collaboration of child GB [boy, 13 years old], ( … ) acting jointly inside the school ( … ), assaulted with slaps, punches and kicks to several parts of the body their schoolmates and children MA and ME [boys, 13 and 14 years old], under the pretext that they had made comments on Facebook that they had not liked.

JH [boy, 15 years old] informed that initially MO [boy, 15 years old] had grabbed him by the neck, kneeing him in the belly and kicking him in the left shoulder and that afterwards, while he was being grabbed by the neck, LP [boy, 15 years old] had slapped him in the face. About 10 minutes later, GF [boy, 14 years old] approached him and slapped him on the neck. It should be noted that, on that same day, LP, via Instagram, threatened him ( … ). The victim informed that he plays football in a team MO has played in the past and that MO has a rivalry with JH.

Still, within this context, there are also unlawful acts that arise from challenges among peers on social media, as noted in the case of the “PZ [boy, 12 years old] who confesses having graffitied a car following an exchange of videos and messages on social media in which he was challenged to do it”.

The potential of social media for communication shows that school extends beyond its walls and is present day and night in young people’s lives, in contrast to what happened when the internet did not exist and contacts after school hours were very limited. Therefore, it is not surprising that most of the facts under analysis involve young people who met in school and can contact each other through social media anytime.

She has known DF [girl, 14 years old] since she was 4-5 years old, since pre-school, and they always attended the same schools and in 7th grade were in the same class. She thought of herself as DF’s friend and older sister, which is no longer the case. It all began with a fight that happened at school, on the last school day, because her schoolmates JH and DF grabbed EV’s drawing folder [girls, both 14 years old], and JH ran away with it, even throwing it at the ground and they both stepped on it. She had no patience to chase them, and she was upset. On ( … ), between 1.18 am. and 2.49 am., EV and the victim [DF] chatted on WhatsApp [aggravated threats, death threats, from EV to DF]. What she said was also based on a story created on the internet (Creepypasta) about Jeff the Killer.

A particularly relevant aspect of this study is the predominance of girls and their groups, most of which bring together female children and young adults, though some of these girls also lead groups of boys. For most of them, social media are a locus of construction of identity and fight for power, and they do not shy away from resorting to violence in various forms. The phenomenon of fight compilations (Cantor, 2000; Haut, 2014), traditionally masculine, has a significant presence in girls’ social media, and the victims are mainly other girls.

There had been a serious assault inside the school. This assault by EM [girl, 13 years old] on FI [girl, 13 years old] had supposedly been filmed with the mobile phone of another student (LU) [girl, 14 years old] ( … ). During a conversation with LU, she first declared that she had not filmed the fight. However, after being told that there were already shares on Snapchat and Instagram, viewed by the assaulted girl’s mother, she finally said that she had filmed it but not shared it. EM could have shared it, as she had asked her for a copy of the video, and she had shared it in a chat on social media. ( … ) It can be concluded that LU did not film the assault by chance because even before the assault began, the image shows the aggressor addressing the victim, and there was even a pause for the recording.

The two female children [CE, 15 years old; CB, 13 years old] envisaged and intended, with at least eight other girls with ages close to theirs, to deprive the victims of their freedom to move by forcing them - using psychological violence - to walk with them for about 300 metres to lead them into an alley. There, they intended to assault AN and AS [girls, both 13 years old] physically and, to increase their humiliation, shame and embarrassment, allow others to record the assault and disseminate it among AN’s friends and acquaintances, which they did.

The victim [boy, 13 years old] was walking along a path to leave the school when a group of schoolmates appeared, surrounded him and cornered him: RA [boy, 11 years old], TA and CA [boys, 13 years old], JA [girl, 14 years old] and GA [girl, 13 years old]. JA grabbed the victim’s sweater and told him 3 times, “come on, hit me”. At the same time, RA and CA used their mobile phones to record what was happening, in particular, the image of the victim. Simultaneously, RA called the victim ( … ), and the child TA told him, “JA, beat him up!” and CA hysterically shouted ( … ). Afterwards, JA assaulted the victim by punching and slapping him several times in the face and all over his body as he covered his face with both hands while JA punched his ears several times. The female child also punched him in the stomach. The assault stopped when the child JA wanted it to stop. The assault was filmed by RA and by the children TA and CA, who intended to record the moment of public humiliation and shaming of their schoolmate and classmate to disseminate it on social media. Under these circumstances, the victim would never have consented to his image being recorded, and the children knew this.

Despite being frightened, GR [girl, 13 years old] and SJ [girl, 14 years old], as described in the report, pointed out the suspects identified in the report as perpetrators of an attempt to enter their home, fulfilling, as mentioned therein, the threats that they had been receiving from the suspects, and they even had a video of an assault that XL [girl, 15 years old] had sent showing a fight between girls. This video was sent via WhatsApp by XL to SJ and understood as a form of threat/coercion aimed at GR.

The third level of analysis identified in the judicial proceedings reveals the potential of social media for - public, semi-public or private - dissemination of the facts by young people, mainly to humiliate the victims, an action that can constitute a new unlawful act. The perpetration of the facts and their dissemination on social media go almost hand in hand.

She also saw CE [girl, 14 years old] upload the photographs on Snapchat, after which she copied them to her mobile phone and uploaded them on Twitter. Since she had not taken the photographs herself nor had been the first to publish them, she thought her responsibility would not be relevant.

When confronted with the video in the case file, she said she recognized herself in it as the person who was hitting NA [girl, 13 years old]. She also recognizes the reference at the top of the video as her own. The reference ( … ) is her handle in one of the Instagram accounts, as she has two accounts on that social media platform [girl, 15 years old].

The teacher informed: that the parent of student ND, duly identified as the victim, had addressed the school board to report that her son had been the target of threats made on a social media platform by students BL [13 years old] and GP [14 years old], both identified as suspects, in the context of which BL had stated that he would stab her son with a knife. Her son believes BL can act on that threat, and he is thus afraid for his own physical well-being and hesitant to go to school. That she made a #print screen# of her son’s mobile phone, as attached, in which BL calls himself ( … ).

In this context, special attention should be paid to the secondary victimization experienced by some young people as their family members reproduce the videos of their assaults on (other) social media, with unpredictable results.

Feeling angry about what had happened to her daughter, and to make sure that her aggressors would be quickly identified and that this type of situation would not happen to other young females, she decided to post the videos on Facebook and ask for help to identify the aggressors. To that effect, she asked her daughter RM [16 years old, sister of the victim] to do it, and she was the one who posted them on the sites ( … ) and ( … ). Before disclosing the videos, she contacted [the media] by telephone. She also gave an interview to [the media]. After these events, her daughter did not return to school.

Other limitations arise from the growing number of views, the failure to promptly remove the videos and the impossibility of controlling sharing on social media. The unlawful acts are not restricted to interactions among peers, and some of the videos posted on social media reveal the victimization of adults, especially teachers.

Several of her female students, identified as the suspects, used a mobile phone inside the classroom to make videos and photographs of her, which they then posted on social media (Facebook and Twitter), adding as a caption to those photos and videos, expressions that attacked her honour.

Even though the Statute on Students and School Ethics only permits the use of smartphones within school premises for educational purposes and subject to prior authorization (Lei n.º 51/2012, 2012), Portugal was one of the European countries where young people least mentioned having rules at school to prevent their use (Simões et al., 2014).

The analysed proceedings show the complexity of taking evidence of the facts through digital technologies in the context of youth justice, and most young people end up cooperating with the authorities. In certain cases, social media play an important role in identifying the suspects/aggressors, making it possible to identify victims and family members who provide the authorities with information that proves decisive for the outcome of the investigation.

6. Conclusion

Access to justice is a basic condition for life in society. Within the framework of the YO&JUST project, this study has sought to understand how social media are used in juvenile delinquency as recorded by the courts, making an original contribution to a topic on which knowledge is scarce.

The prevalence of social media in the lives of young people is apparent compared to just under a third of the base population in the period under analysis. Multiple participation, in which a young person has several profiles on one and/or on various social media platforms simultaneously, is dominant. Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp and Facebook are the most represented, without noticeable differences in how they were used in the facts identified. Some of the proceedings highlight the ease with which young people create fake profiles, especially on Facebook, to circumvent the access restriction relating to a minimum age. The findings of this study illustrate the “onlife” (Floridi, 2017), the hallmark of the ways of life of young people in current times. These young people have never known a world without digital engagement, and for whom social media are everyday spaces of social inclusion and participation.

Part of the analysed facts initially reflected social dynamics associated with the developmental tasks of adolescence (i.e., construction of identity, discovery of sexuality, gaining autonomy and social participation), but that repeatedly evolved into transgression, often causing great harm to others. That trend that used to characterize delinquent practices in the physical world is now renewed by the speed of the escalation of violence, the greater number of young people involved in these acts and the broad reach of their public dissemination, which leads to the secondary victimization of the offended. There is a significant overrepresentation of girls as perpetrators of unlawful acts, especially those involving a high degree of violence, with numbers very close to those of boys. This trend differs from the one commonly identified in the delinquency officially recorded at the national and international levels.

Most of the unlawful acts identified are related to school and the interactions that originated in it, which, in this digital age, extend beyond school hours and premises. The constant interaction between victims and aggressors facilitated by social media, at any time and in any place, has at its epicentre the perception that personal honour has been attacked and requires reparation. From there, it is a short step to violence, which sometimes leads to a reconfiguration and exchange of roles between victim and aggressor, which is not always easy to prove. More than the anonymity afforded by the digital, what stands out is the need for affirmation in public and/or semi-private space, and violent action is the catalyst to gain respect through the immediate gratification offered by social media. Other children, especially acquaintances/friends, are the main victims. To a much lesser extent, the victims are also adults, especially teachers.

The growing complexity of criminal investigation in the context of youth justice is evident, and three levels of social media use in the perpetration of unlawful acts were identified. The first, similar to what has been described as violent and organized crime perpetrated by adults, reveals the use(s) of these media for planning/organization. The second and third levels are often linked, combining the execution with the subsequent dissemination of unlawful acts on social media. In some proceedings, the dissemination itself constituted a new unlawful act, especially in situations relating to child pornography.

This study is limited to the most serious cases subject to a decision issued within the framework of youth justice in Portugal and, therefore, in which there is clear proof of harm. The importance of not restricting the analysis of delinquency to a dichotomous view of the online and the offline worlds is one of the main recommendations. Given the nature of children and young people’s involvement with digital technologies in their everyday life, there is a need for further research on the appropriateness of the categories, instruments and models used in this study to assess the profile of the perpetrator of the unlawful acts. Addressing this question will be instrumental in understanding the relationship between the state and young citizens, an endeavour currently pursued under the YO&JUST project.

Mitigating risks and promoting opportunities associated with the use of social media should be a priority for professionals working with young people. In line with other research on online aggression, findings show the need to offer educational programmes and communication tools aimed at specific groups, such as girls, given the prevalence of their digital practices over others.

It is essential to acknowledge that not all reasons for violating the rules (will) lead to a delinquent trajectory and that all young people need support to develop digital skills and learn to mediate risks-opportunities. Based on an ecological perspective, the integrated collection of data about the activities in digital environments in each young person’s path is vital for future action but not yet a very common practice in the country. Intense and highly technical challenges await the courts dealing with matters relating to family, children and young people - where, from the base to the top, the resources are (very) few -, and there is an ever-growing need to employ/update existing knowledge and work in cooperation with experts, given the multidimensional nature of these situations.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by national funds through the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. under the Scientific Employment Stimulus - Individual Call (CEEC Individual) -2021.00384.CEECIND/CP1657/CT0022. The data presented is the result of a research project supported by the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through an individual postdoctoral grant (SFRH/BPD/116119/2016) with co-funding from the European Social Fund, under the POCH - Human Capital Operational Program, and from national funds of the MCTES - Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education. Data collection was authorized by the Portuguese High Council for the Judiciary (2019/GAVPM/1436) and by the judges responsible for the cases. This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within the scope of the project «UIDB/04647/2020» of CICS.NOVA - Interdisciplinary Centre of Social Sciences of NOVA University Lisbon.

REFERENCES

APAV - Associação Portuguesa de Apoio à Vítima. (2021). Manual de formação ROAR: Apoio especializado a vítimas de cibercrime. https://apav.pt/publiproj/images/publicacoes/Manual_de_formacao_PT.pdf [ Links ]

Baldry, A., Balya, C., & Farrington, D. (Eds.). (2018). International perspectives on cyberbullying. Prevalence, risk factors and interventions. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

boyd, D., & Ellison, N. (2008). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer - Mediated Communication, 13, 210-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x [ Links ]

Cantor, J. (2000). Media violence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27(2), 30-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00129-4 [ Links ]

Carvalho, B. J. de., & Marôpo, L. (2020). “Tenho pena que não sinalizes quando fazes publicidade”: Audiência e conteúdo comercial no canal Sofia Barbosa no YouTube. Comunicação e Sociedade, 37, 93-107. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.37(2020).239 [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. J. L. (2019). Delinquência juvenil: Um velho problema, novos contornos. In L. M. Caldas (Ed.), Jornadas de direito criminal: A Constituição da República Portuguesa e a delinquência juvenil (pp. 77-106). Centro de Estudos Judiciários. http://www.cej.mj.pt/cej/recursos/ebooks/penal/eb_ JornadasSantarem2019.pdf [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. J. L. (2021). Youth justice, ‘education in the law’ and the (in)visibility of digital citizenship. In M. J. Brites & T. S. Castro (Eds.), Digital citizenship, literacies and contexts of inequalities (pp. 67-78). Edições Universitárias Lusófonas. https://research.unl.pt/ws/portalfiles/portal/36028015/CARVALHO_Maria_Joao_Leote_2021_Youth_Justice_Education_in_the_Law_and_Digital_Citizenship.pdf [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. J. L., Duarte, V., & Gomes, S. (2021). Female crime and delinquency: A kaleidoscope of changes at the intersection of gender and age. Women & Criminal Justice. Publicação eletrónica antecipada. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2021.1985044 [ Links ]

Donner, C. M., Jennings, W., & Banfield, J. (2015). The general nature of online and off-line offending among college students. Social Science Computer Review, 33(6), 663-679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314555949 [ Links ]

Eisenstein, E. (2013). Desenvolvimento da sexualidade da geração digital. Adolescência & Saúde, 10(1), 61-71. https://cdn.publisher.gn1.link/adolescenciaesaude.com/pdf/v10s1a08.pdf [ Links ]

Fang, T. (2019, 21 de dezembro). We asked teenagers what adults are missing about technology. This was the best response. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/12/21/131163/ youth-essay-contest-adults-dont-understand-kid-technology/ [ Links ]

Floridi, L. (2017, 9 de janeiro). We are neither online nor offline, but onlife. Chalmers. https://www.chalmers.se/en/areas-of-advance/ict/news/Pages/Luciano-Floridi.aspx [ Links ]

Goldsmith, A., & Wall, D. (2019). The seductions of cybercrime: Adolescence and the thrills of digital transgression. European Journal of Criminology, 1-20. Publicação eletrónica antecipada. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370819887305 [ Links ]

Haut, F. (2014). Cyberbanging: When criminal reality and virtual reality meet. International Journal on Criminology, 2, 22-27. https://doi.org/10.18278/ijc.2.2.3 [ Links ]

Lei n.º 4/2015, de 15 de janeiro, Diário da República n.º 10/2015, Série I de 2015-01-15 (2015). https://dre.pt/ dre/detalhe/lei/4-2015-66195397 [ Links ]

Lei n.º 51/2012, de 5 de setembro, Diário da República n.º 172/2012, Série I de 2012-09-05 (2012). https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/51-2012-174840 [ Links ]

Livingstone, S., & Mason, J. (2015). Sexual rights and sexual risks among youth online: A review of existing knowledge regarding children and young people’s developing sexuality in relation to new media environments. European NGO Alliance for Child Safety Online. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64567/ [ Links ]

Livingstone, S., & Stoilova, M. (2019). Using global evidence to benefit children’s online opportunities and minimise risks. Contemporary Social Science, 16(2), 213-226. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2019.1608371 [ Links ]

Mascheroni, G., Cino, D., Mikuška, J., Lacko, D., & Smahel, D. (2020). Digital skills, risks and wellbeing among European children: Report on (f )actors that explain online acquisition, cognitive, physical, psychological and social wellbeing, and the online resilience of children and young people. ySkills. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5226902 [ Links ]

Matos, M. G. & Equipa Aventura Social. (2018). A saúde dos adolescentes portugueses após a recessão. Relatório do estudo Health Behaviour in School Aged Children (HBSC) em 2018. Aventura Social. https://fronteirasxxi.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/A-SA%C3%9ADE-DOS-ADOLESCENTES-2018.pdf [ Links ]

McCuddy, T. (2021). Peer delinquency among digital natives: The cyber context as a source of peer influence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 58(3), 306-342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427820959694 [ Links ]

Mojares, R., Evangelista, C., Escalona, R., & Ilagan, K. (2015). Impact of social networking to juvenile delinquency. International Journal of Management Sciences, 5(8), 582-586. https://research.lpubatangas. edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IJMS-Impact-of-Social-Networking-to-Juvenile-Delinquency.pdf [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. V., & Carvalho, M. J. L. (2022). Traços e retratos da imprensa on-line sobre o uso das tecnologias digitais de informação e comunicação como ferramentas de suporte ao crime organizado em Roraima, Brasil. Revista de Direito da Cidade, 14(1), 457-493. https://doi.org/10.12957/rdc.2022.64723 [ Links ]

Patton, D. U., Hong, J. S., Ranney, M., Patel, S., Kelley, C., Eschmann, R., & Washington, T. (2014). Social media as a vector for youth violence: A review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 548-553. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.043 [ Links ]

Pereira, S., Ponte, C., & Elias, N. (2020). Crianças, jovens e media: Perspetivas atuais. Comunicação e Sociedade, 37, 9-18. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.37(2020).2687 [ Links ]

Ponte, C., & Batista, S. (2019). EU Kids Online Portugal. Usos, competências, riscos e mediações da internet reportados por crianças e jovens (9-17 anos). EU Kids Online; NOVA FCSH. [ Links ]

Ponte, C., Batista, S., & Baptista, R. (2022). Resultados da 1ª série do questionário ySKILLS (2021) - Portugal. ySkills. https://www.icnova.fcsh.unl.pt/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2022/02/Relat%C3%B3rio-1%C2%AA-s%C3%A9rie-Portugal-2.pdf [ Links ]

Ponte, C., Carvalho, M. J. L., & Batista, S. (2021). Exploring European children’s self-reported data on online aggression. Communications, 46(3), 419-445. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2021-0050 [ Links ]

Rovken, J., Weijters, G., Beerthuizen, M., & Laan, A. (2018). Juvenile delinquency in the virtual world: Similarities and differences between cyber-enabled, cyber-dependent and offline delinquents in the Netherlands. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 12(1), 27-46. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1467690 [ Links ]

Sibilia, P. (2008). O show do eu: A intimidade como espetáculo. Nova Fronteira. [ Links ]

Simões, J. A., Ponte, C., Ferreira, E., Doretto, J., & Azevedo, C. (2014). Crianças e meios digitais móveis em Portugal: Resultados nacionais do projeto Net Children Go MoBile. CICS.NOVA − FCSH/NOVA. https://netchildrengomobile.eu/ncgm/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ncgm_pt_relatorio1.pdf [ Links ]

Staksrud, E. (2009). Problematic conduct: Juvenile delinquency on the internet. In S. Livingstone & L. Haddon (Eds.), Kids online: Opportunities and risks for children (pp. 147-157). Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qgvds.17 [ Links ]

Stern, S. (2008). Producing sites, exploring identities: Youth online. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth identity and digital media (pp. 95-118). MIT Press. [ Links ]

Storrod, M., & Densley, J. A. (2017). ‘Going viral’ and ‘going country’: The expressive and instrumental activities of street gangs on social media. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(6), 677-696. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1260694 [ Links ]

Vilela, B. (2019). Jovens e redes sociais - Efeitos no desenvolvimento pessoal e social [Dissertação de mestrado, Escola Superior de Educação de Bragança]. Biblioteca Digital do IPB. http://hdl.handle.net/10198/20576 [ Links ]

Wall, D. (2007). Cybercrime: The transformation of crime in the information age. Polity. [ Links ]

Received: March 30, 2022; Accepted: June 03, 2022

texto em

texto em