Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.43 Braga jun. 2023 Epub 30-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.43(2023).4461

Thematic Articles

Mapping Maps of Alternatives: Diverse Economies and Modes of Mapping in Common

i Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

ii Instituto de Sociologia, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

iii Instituto de Investigação em Design, Media e Cultura, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

iv Departamento de Artes Visuais, Escola Superior Artística do Porto, Porto, Portugal

Este artigo tem como objeto de estudo seis mapas produzidos em Portugal e na Catalunha, enquanto dispositivos comunicativos de outros mundos possíveis. Assumindo a crescente importância dos mapas digitais na sociedade em rede, queremos contribuir para entender mais sobre o seu papel na edificação de alternativas à economia dominante em tempos de crises sistémicas. Que aprendizagens surgem dos mapas que propõem desvios dos roteiros capitalistas? Que entendimentos nos trazem quer sobre os próprios mapas, quer sobre os modos de mapear e as desejadas alternativas? Mais do que explorar os mapas como produto, procura-se contribuir para a compreensão das forças intersticiais da sua pré-produção, produção e reprodução. À luz das teorias dos comuns, são auscultadas dinâmicas de mapeamento colaborativo de economias diversas: diversas quanto às suas políticas de conhecimento, quanto às suas formas de governança e participação e, logo, quanto ao modo de manusear as tecnologias digitais. O objeto de estudo define-se e une-se, na sua variedade, pelas ideias de coletivo e de comum. Os dados provêm da observação direta de mapas e de entrevistas feitas aos intervenientes. A análise é predominantemente qualitativa e visa organizar constatações e desafios relevantes, extrapoláveis a partir dos testemunhos, práticas e objetos observados.

Palavras-chave: mapeamentos colaborativos; comuns digitais; economias diversas

This paper’s object of study focuses on six maps produced in Portugal and Catalonia as communication devices of other possible worlds. Assuming the growing importance of digital maps in the network society, we want to contribute to learning more about their role in constructing alternatives to the dominant economy in times of systemic crisis. What lessons emerge from maps that propose deviations from capitalist roadmaps? What understandings do they provide about the maps themselves, ways of mapping, and the hoped-for alternatives? Rather than exploring maps as a product, we seek to contribute to an understanding of the interstitial forces of their pre-production, production, and reproduction. In the light of the theories of the commons, the dynamics of collaborative mapping of diverse economies are explored: diverse in terms of their knowledge policies, modes of governance and participation and, therefore, in how they handle digital technologies. The object of study is defined and united, in its variety, by the ideas of collective and commons. The data comes from direct observation of maps and interviews with stakeholders. The analysis is predominantly qualitative and aims to organise relevant findings and challenges, which can be extrapolated from the observed testimonies, practices and objects.

Keywords: collaborative mappings; digital commons; diverse economies

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which humanity is always landing. -Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism

And the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.

-Jorge Luis Borges, On Exactitude in Science

1. Introduction

In the daily life of the network society, the use of digital maps is increasingly common. These devices aimed at the synthetic understanding of complex realities have become discrete agents of our everyday life. Depending on the criteria of their authors and their production processes, maps reveal or hide the places/realities they desire/reject; they categorise and relate what one wants to make visible; they highlight and point, or not, to what one has chosen as relevant. And the same maps also have the potential gift of sharpening the imagination and making other worlds known - particularly those that deviate from the well-known home-work-consumption routes dominated by relationships mediated by capital in a globalised market economy.

On the other side of the capitalist roadmaps - and often off the radar - persist spaces driven by different logics of relationships between people and between people and the territory they inhabit. Community spaces, “alternative” projects, neighbourhood associations, places where “diverse economies” (Gibson-Graham, 2008) are born and grow, promote - and aim at - a different reading from that offered by conventional models of the market, work and enterprise. Among a plurality of possible approaches, they recognise non-monetised symbioses of work, alternative modes of (co)production, consumption, distribution and exchange of goods and services, always driven by motivations that move away from the merely lucrative purposes of mercantile competition. They are united by the mission of prefiguring, and soon building, post-capitalist economies.

Portugal has several national, regional or local maps aggregating multiple initiatives. These range from ecovillages to urban gardens, cooperative shops, independent educational projects, community restaurants, consumer groups or permaculture projects - universes of practices often under the institutionalising social innovation and entrepreneurship label (Social Business School & Instituto Padre António Vieira, 2015), leaving out “those experiences which, being community-based and informal - many of them strongly rooted in the past, such as peasant mutual aid or worker mutualism -, are outside an imaginary of economic growth and social control by the State” (Hespanha et al., 2015, p. 469), as Hespanha et al. (2015) point out, reinforcing “the need to make initiatives visible and to demarcate the limits between Solidarity Economy, Social Economy and Social Entrepreneurship” (p. 469) in Portugal.

Our object of study includes a set of maps revealing the universe of alternative economic practices identified in Portugal and Catalonia. Although some academic studies focus on (or from) maps of alternatives in Portugal (Balsa et al., 2016; Baumgarten, 2017; Ferreira & Almeida, 2021; Guerreiro, 2013; Hespanha et al., 2015; Mourato & Bussler, 2019; Nogueira, 2018; Soares, 2017; Valentim, 2012), there are no known approaches under the lens of communication processes. More than resorting to the mere use of georeferenced data from existing maps or studying the substance or disparity of the concrete alternatives covered here, we aim to “meta-map”, that is, to contribute to refining the collaborative mapping processes of diverse economies.

The purpose is to study the potential of maps as a meta-territory/good/commons, which we have done in light of a model of analysis of the digital commons (Fuster Morell & Espelt, 2018), exploring mapping processes and their ability to cultivate continuities regarding governance and participation, economic model, technology and knowledge. As such, the maps as products are only meant to analyse the relationship between collaborative mapping and practices of “doing-in-common”.

2. Diverse Economies and Modes of Mapping as Commoning

The multiple crises of late capitalism have prompted ordinary people in various parts of the world to experiment with alternative modes of production, consumption and exchange in their daily lives (Castells et al., 2017; Conill et al., 2012), creating and nurturing “other economies” often referred to as the solidarity, sustainable, transformative, sharing or circular economy, among other possible names. Although the nuances, in detail, may refer to different ethics and approaches, we see a common goal as a whole: the need to create ecologically more sustainable and socially just alternatives to the dominant economic model. The term “diverse economies”, coined by the critical geography duo Gibson-Graham (2008), takes in the heterogeneity of ongoing experiences, united by a greater or lesser degree of rupture with the dominant system.

In these contexts (as in others), digital cartography and geographic information systems have been adopted as tools to promote, connect, inform, locate, document and make alternatives visible (Borowiak, 2015; Drake, 2020; Labaeye, 2017; Safri et al., 2017). These are also “revealing economic diversity, resisting capitalocentric discourse and reading for difference” (Drake, 2020, p. 496), thereby deconstructing and enabling “unravel capitalonormativity and to highlight the radical heterogeneity of economic identities and relationships and trajectories” (Gibson-Graham, 2020, p. 481).

With the motto “there are plenty of alternatives”, the international collective TransforMap1 mobilised a broad-based attempt to map maps of alternatives. Contrary to the old neoliberal mantra of T.I.N.A. - “there is no alternative” - it proposed to create an online platform that would “visualize the myriad of alternatives to the dominant economic thinking on a single mapping system” (TransforMap, n.d., para. 1). The collective was based on a critical position towards the ownership of mapping platforms and their data and defended “mapping as a commons”, defining its guiding principles (Helfrich, 2016), of which we highlight: maps as shared resources and commoning practices in mapping; open access through the adoption of non-proprietary free software; and the involvement of communities in mapping.

Indeed, in collaborative mappings, as in any collective action, the theories of the commons are a valuable contribution. Since time immemorial, communities have organised autonomously in the communal management of land for grazing or cultivation or in the sharing of water for irrigation (Ostrom, 1990). However, commons exist not only in the rural and natural world: we can find urban commons in cities and commons in the digital sphere, with the advance in information and communication technologies and the new possibilities for peer production and sharing (Benkler, 2006). The commonality of all these commons is their bringing together communities around shared resources outside the market scope and the state’s purview, defining rules for their collective governance.

In order to gauge the democratic qualities of digital commons, Fuster Morell (2018) developed an analytical model based on five dimensions: “governance”, “economy”, “knowledge”, “technology” and “social responsibility”, having later added the “impact” dimension (Fuster Morell & Espelt, 2019). Concerning governance, the indicators proposed by the model are the type of organisation (public, private or democratic, such as associations or cooperatives) and the existence or not of participation mechanisms by members. Regarding the economic strategy, the indicators are the goal (profit or nonprofit) and transparency (whether members have access to economic information). On the technological base, the model advocates the adoption of free and open-source software and decentralised architectures. As for knowledge policies, the use of copyleft licences and the adoption of open data formats contribute to the pro-commons qualities of the initiatives. Social responsibility refers to the project’s social and environmental inclusion policies. The impact dimension refers to the number of people affected by the initiative. This model of analysis is structuring the study.

3. Methodological Note

3.1. Choice of Territories and Cases

The choice of territories in Portugal and Catalonia is motivated by this article’s inclusion in an ongoing PhD research, which relates these regions regarding their different economies. The Portuguese cases are more thoroughly studied within this research, and the Catalan case is taken as counterpoint for analysis.

The selection of the maps adhered to two primary conditions: they emerged at the initiative of citizens or civil society organisations (as opposed to the academia), and they focused on alternative and solidarity economies (as opposed to entrepreneurship and social innovation). The choice sought to provide a broad picture concerning the mapping approaches, territorial scopes, scales, purposes and criteria explained below.

In Portugal, we selected the Rede Convergir (“mapping sustainable initiatives”), the project Alternativas (“local change initiatives”), SUSY (“sustainable and solidarity economy”), Transição Portugal and the map of Regional Autonomy in South of Portugal. From Catalonia, we selected the responsible consumption map Pam a Pam2 (https://pamapam.org), which we consider to be a reference within the solidarity economy in the region and, especially, given its replication potential, as the map source code is available and has been reused by other initiatives in other regions.

3.2. Mapping the Maps

Both the collection and the analysis of the objects of study materialise a qualitative approach. The six maps produced in Portugal and Catalonia were translated into results using the pro-commons qualities proposed by Fuster Morell (2018) as a framework for organising the collected data. The collections were obtained through ethnography actions dedicated to the maps and peripheral materials identified online and offline or through semi-structured interviews. Further in detail:

Online ethnography: in 2019, the contents of the mapping platforms under analysis were extracted and systematised separately in a diagram and combined in a summary table containing the general description of each map, its goals and criteria, the year of launch, the number of initiatives mapped and the technology adopted. The categories devoted to including points on each map were also surveyed and organised.

Interviews: five interviews of about 60 minutes each were conducted through video conferencing between September and October 2019, with one person responsible for each map in Portugal. We prepared a semi-structured interview script with a flexible sequence of questions. The questions addressed the origins of mapping, the criteria for inclusion/exclusion of initiatives, the modes of governance and participation in mapping, the economic model of funding, the technology used in its development and the data policy adopted. Interviewees were also asked about their thoughts on the challenges experienced in the process and the needs identified for future developments. In one case, where the Portuguese map was integrated into a European project, there was also email correspondence with the wider group to clarify technical issues. The interviews were anonymised and transcribed in full. The transcription generated around 30 pages of text, which were analysed by highlighting extracts on the mappings’ origins, criteria and goals and the main challenges in the projects. Data on the dimensions defined in the Fuster Morell (2018) model were also extracted. In the specific case of the “impact” dimension, and given that we had no other relevant data, we resorted to quantifying the initiatives included in each map.

Collection in the Catalan case: here, the interview was replaced by data collected at events where we were with the Pam a Pam team. At Catalonia’s Solidarity Economy Fair 2019, we had the opportunity to talk informally about the mapping and collect materials produced by the project; between March 2019 and January 2021, it was possible to attend online discussion forums of Pam a Pam’s Information and Communication Technologies Commission. We could also access secondary sources based on the abundant existing literature, namely, previous studies by Espelt et al. (2019) and Fuster Morell and Espelt (2019).

4. Mapping Maps of “Alternatives” in Portugal

We now present the various mappings according to the criteria defined above. We extract a diagram from each mapping project explaining its structure and taxonomy. The immense learning we extracted from the interviews is summarised in selected quotes.

4.1. Rede Convergir

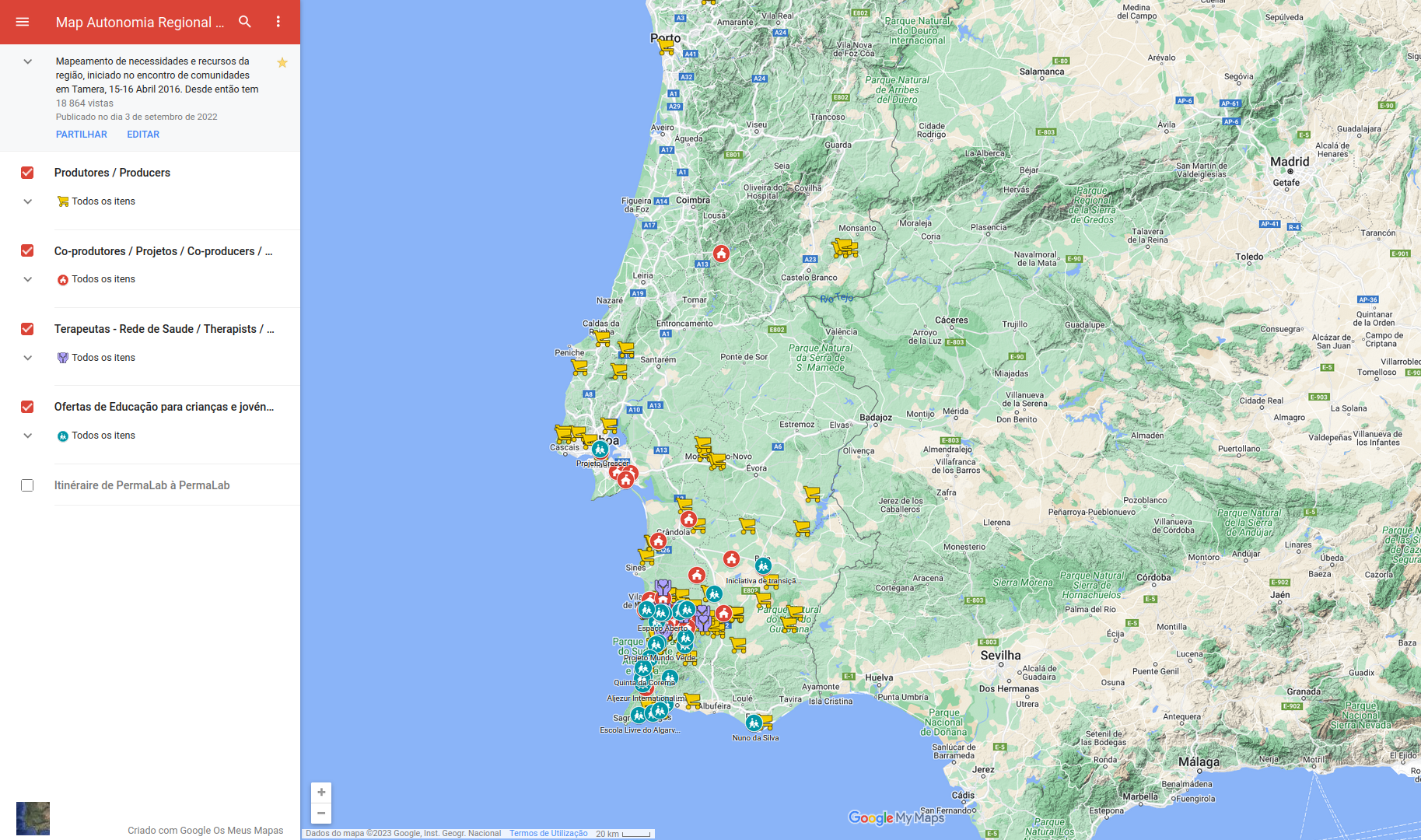

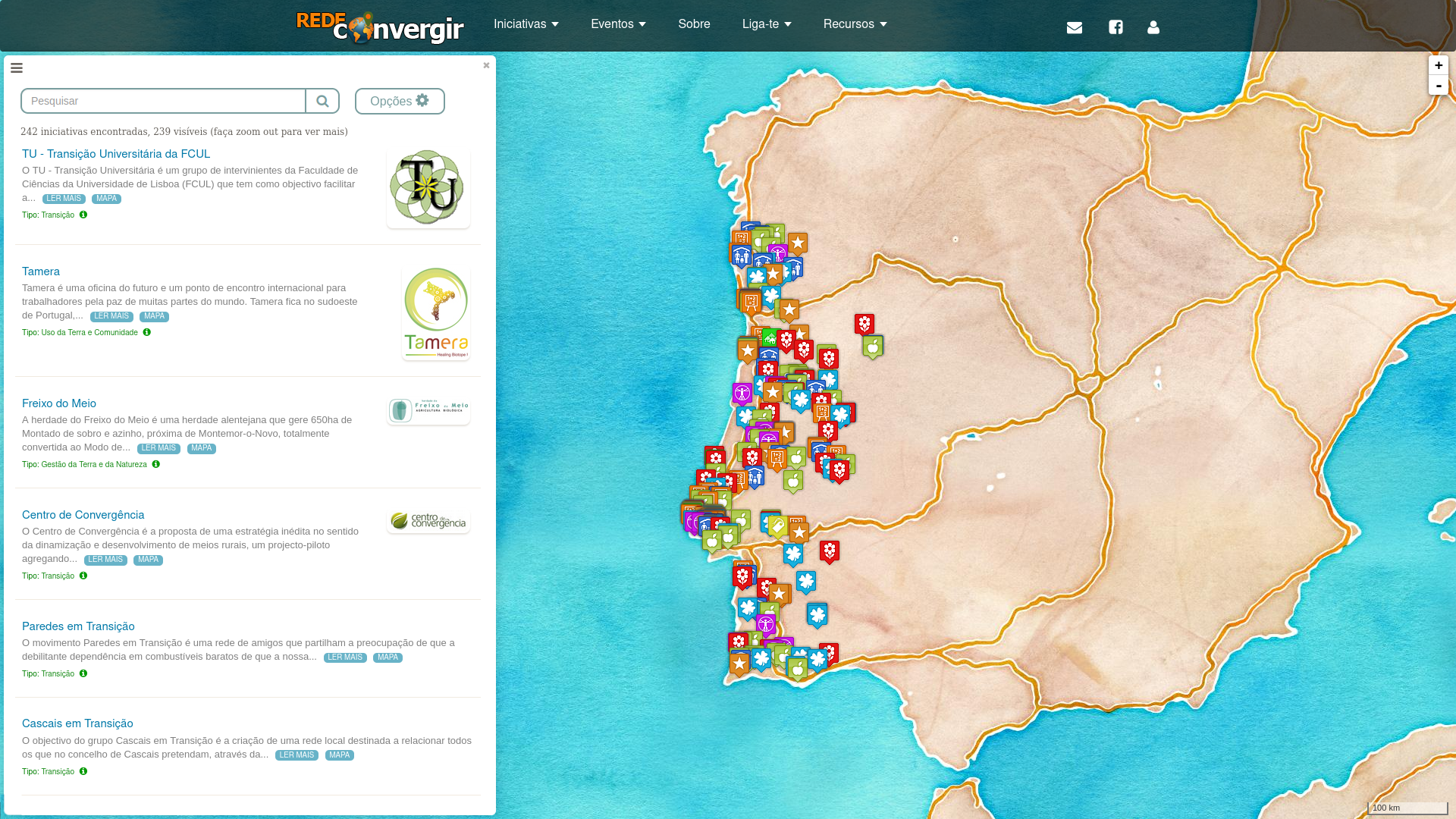

The Rede Convergir is probably the best-known map of alternatives in Portugal: with the most self-referenced initiatives in the country (n=242; see Figure 1), it is frequently referred to in academic studies. Launched in 2012, it is the oldest of the maps covered in this study.

From Mapa das Iniciativas, by Rede Convergir, n.d.-a. (https://redeconvergir.net/iniciativas)

Figure 1 Screenshot of the Rede Convergir map of Portugal’s mainland (March 2023)

Its mission is to “map sustainable and inspiring initiatives so that we can network, cooperate, coordinate and leverage our synergies to contribute to a balanced and sustainable society and human life in harmony with the surrounding environment” (Rede Convergir, n.d.-b, para. 1), Convergir emerged from an international meeting of ecovillages in Tamera in July 2011, hosted by the international network Global Ecovillage Network. The meeting prompted the creation of a working group concerned with the “dispersion of energies in the scope of sustainability initiatives” and the desire to “discuss the construction of a platform for mapping initiatives on national territory” (Rede Convergir, n.d.-b, para. 24).

“Look here, [sic] with this initiative, we will be co-creating what this will be, we don’t really know, we have an idea”, and for a year, every fortnight, we had online meetings where we discussed several things ( ... ) one of them is the name: we will call it “rede” [network] because what we want is to map the network, and “convergir” [converge] - because it is not only permaculture projects or ecovillages, ( ... ) it is actually a convergence of projects. These ideas want to be alternatives to the current model. (Teodoro, interview, October 17, 2019)

Guided by principles of cooperation and reciprocity, transparency, self-regulation and organisation, scope and geographical proximity, and holarchy, the network is managed by volunteers on a rotational basis. The main governance functions are divided between moderators and guardians: the former approve new initiatives submitted on the map, manage the project overall and take on web programming and communication tasks; the latter is responsible for the integrity and promotion of the network, although, according to Teodoro, “there hasn’t been any email exchange between us [guardians] for over a year”.

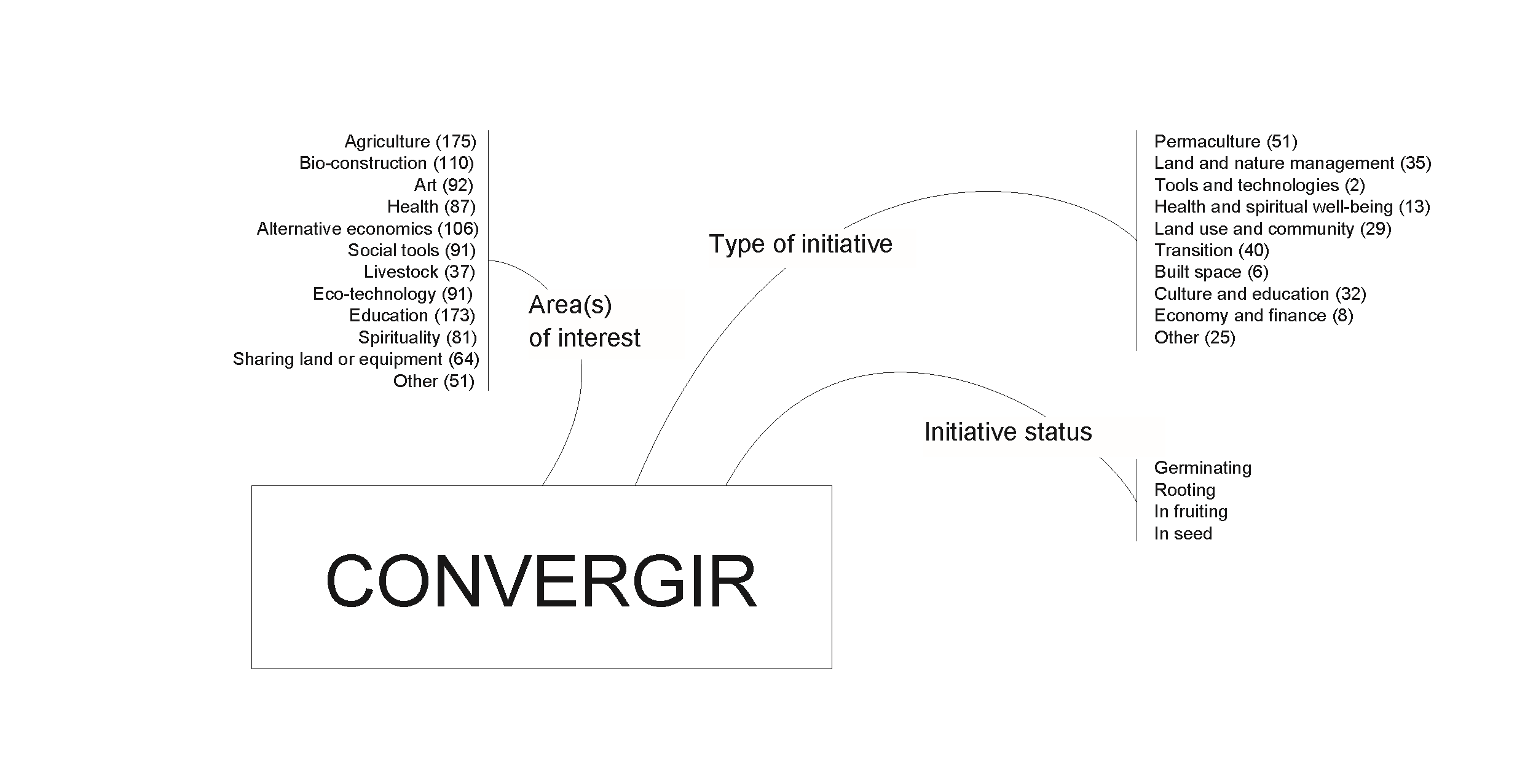

Anyone can propose a new point on the map by filling out an online form that includes contacts, address, website, logo, date of creation, characterisation, target audience, the scope of direct interaction, receptivity to visits, scope (rural/urban/both), number of people involved, land area, general description. The initiative’s “status” is also included as to its moment (see Figure 2). From “in germination” to the opposite condition of “deactivated” (and, therefore, the “in seed” status, which has given or will give rise to new projects and/or initiatives, and does not entail its elimination from the map).

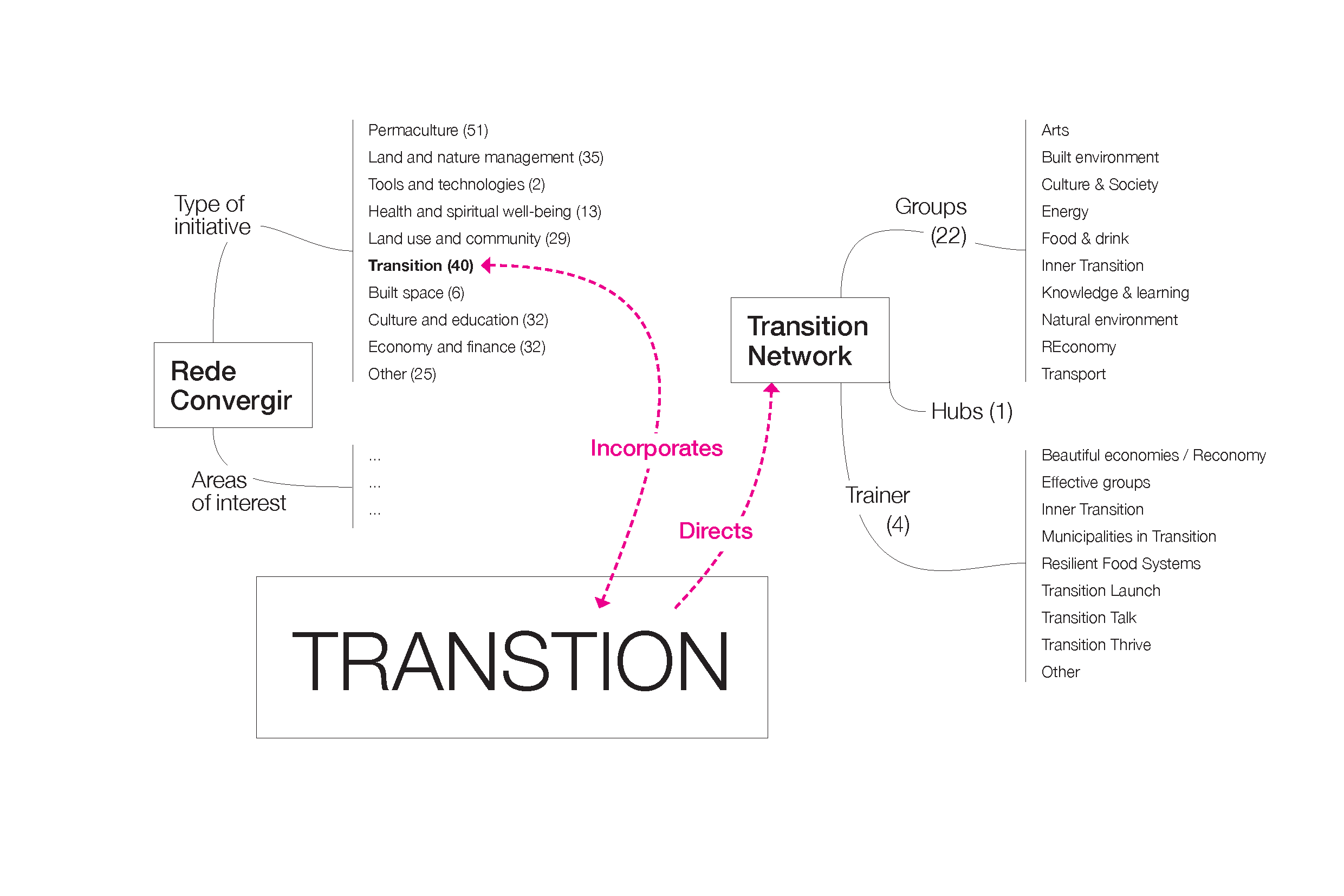

Figure 2 Main categories (“filters”) of the Rede Convergir map. Each initiative is assigned a “type”, a “status”, and one or more “areas of interest”

After submission, the proposal is approved (or not) by the moderators, who check whether it complies with Rede Convergir’s (n.d.-b) main criteria: (a) initiatives that “promote sustainability” (para. 11); (b) “are contactable, viewable and georeferenced” (para. 12); and (c) “are somehow inspiring” (para. 13). After publication, the initiative is displayed on the map and has a dedicated page, which promoters can and should manage. Besides the map, the platform provides a collaborative events planner, a newsletter and a Facebook page, although with no updates since 2019-2020.

In the interview with Teodoro (October 17, 2019) is highlighted the fact that in Convergir, “the map is self-mapping, and it takes time, requires trust”, as opposed to the “focus on quantity” that leads to “poor quality information”.

The interview has a hot spot devoted to governance and visibility modes:

there was some talk about the danger, man... I don’t know if it’s only in Portugal that there’s this wall, this dragon of centralisation from the alternative projects. People are very suspicious. ( ... ) It became very clear that the Rede Convergir will never talk about the projects, its centralisation and mapping for the sake of costs and know-how, but having people lending their faces for the Rede is not even convenient. (Teodoro, interview, October 17, 2019)

The theme of “dragons” continues: “how do you create tools that centralise information but decentralise power?”, a question added to others related to the sustainability and availability of people for the project: “how do you work seriously and [with] some quality in a project for which you are volunteering? And however much you like it when you move a mile a minute, we all do, we are no exception, it becomes difficult” (Teodoro, interview, October 17, 2019).

The future aspirations mentioned include: updating the mapped projects; technical refinement to give participants greater autonomy in updating the information; evidence of relationships between points in the network, namely, regarding projects originating in others.

4.2. Alternativas

The project Alternativas - Local Experiences for Global Transformation was developed between 2016 and 20183 by five Portuguese organisations working on issues related to education for development and global citizenship - Fundação Gonçalo da Silveira, Faith and Cooperation Foundation, CooLabora, Rede Inducar and Politécnico de Leiria, co-financed by the Instituto Camões. According to the project’s website (https://www.projetoalternativas.org/), the goal is to contribute to a new understanding of this relationship between local and global based on processes of social transformation and generate reflection and critical thinking in formal, non-formal and informal educational environments.

The project’s outcome was a documentary, an open letter for social transformation, teaching resources and a map of “local change initiatives”.

The map was not our purpose; the map is only a means. The purposes of the Alternativas project are the pedagogical processes and the educational resources... and this map somehow also feeds these pedagogical processes. ( ... ) For us, mapping is a valid instrument in itself, and having various maps with different criteria is not confusing for us; it is a sign of vitality, of activity; we are in an area that has so little visibility, so little knowledge, so little scope ( ... ) that the fact that there are various actors motivated to undertake this type of initiative is positive ( ... ) in valuing diversity if we do it at the level of people and societies it also makes sense to do it at the level of processes and mappings. (Ulisses, interview, October 15, 2019)

The team defined five key mandatory requirements for including the initiatives: (a) having a collective dimension; (b) coherence with the principles and values underlying Alternativas’ vision of social transformation: social justice, democracy and sustainability; (c) democratic and shared decision-making among all (including those to whom the action is directed); (d) local rooting and interrelation with the territory; and (e) being ongoing at the time of the mapping. Another five reference criteria were also defined: the “learning disposition”, the “interrelation with other initiatives, networks and other actors”, the “experimental character”, the approach to issues considered as priorities by the team (such as women’s participation and power relations) and the “transformation of interpersonal relations and collective bonds” (Alternativas, n.d.-a).

The mapping was carried out following a “collaborative, critical and dialogic process”, which incorporated the answers to a questionnaire based on the vision of social transformation and criteria defined by the team.

It had around 85 answers, but around 45 were not included in the map because some criteria, namely regarding issues linked to internal democracy, more or less open to participation, and collective dynamics, prevented us from considering ( ... ) many of them are unipersonal. Many cannot be considered civil society, although they use formal civil society forms, for example, associations dominated by two or three municipalities. (Pandora, interview, October 8, 2019)

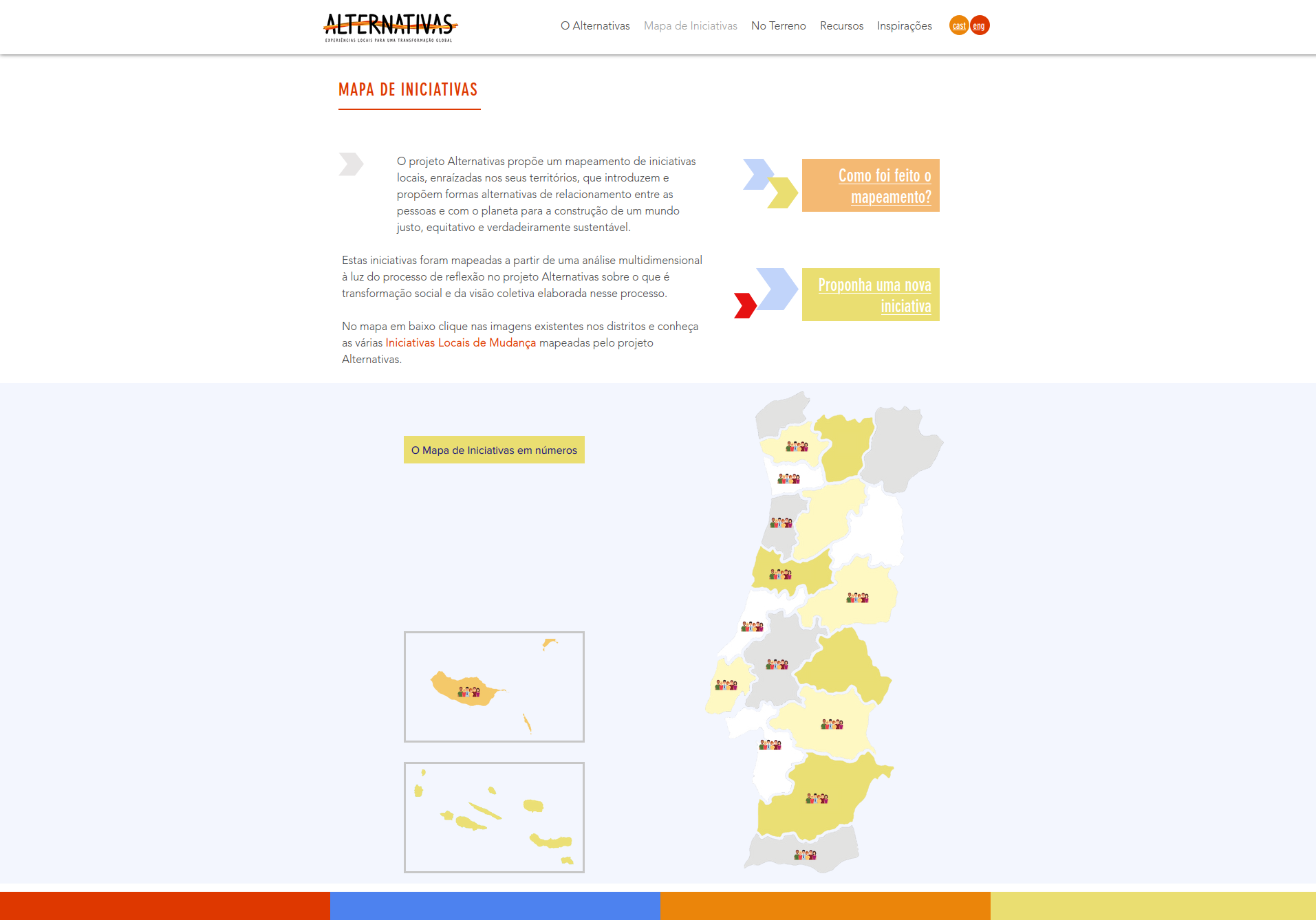

Unlike the other maps in this study, there is no characterisation taxonomy of the initiatives from which to navigate. The points are simply grouped by district (see Figure 3), from which lists of initiatives can be accessed, each with a PDF fact sheet.

From Mapa de Iniciativas, by Alternativas, n.d.-b (https://www.projetoalternativas.org/mapa-de-iniciativas)

Figure 3 Screenshot of the Alternativas map (March 2023)

4.3. Regional Autonomy in South of Portugal

The map of the Regional Autonomy in South of Portugal (Figure 4) is a spontaneous initiative that stemmed from a community meeting in Tamera in 2016 to map the region’s needs and resources. “Since then, it has been permanently updated by all those involved in this”, giving a brief description on Google Maps (n.d.).

The map registers 188 references at the time this article was finalised, including 114 producers, 34 “co-producers/projects”, 11 therapists (“health network”) and 29 educational projects (Figure 5).

The independent survey of resource needs and availability among the 50 or so people who attended the said meeting was mobilised after one of the participants showed the intention of setting up a shop or supply centre for products in the region, as another of the participants and initiator of the map recalls:

before we discuss what we need for regional autonomy and where the logistics centre is, maybe we should map ourselves, who are the people here, and where they are in the territory; we can even understand that the centre of gravity, the centroid of these people is maybe somewhere else and not [in the place proposed by the other] ( ... ). I had my computer, I opened a Google Maps and started mapping ( ... ), what do they have to offer and what do they need? What do they produce, and what do they need to buy? At the end of the mapping, or after a dozen people, we realised that maybe this, it [sic] also needs to introduce a transport dimension, ( ... ) people that move from one place, have regular routes and can act as couriers, do transport services for others ( ... ) and not only products but also services ( ... ), I don’t know, there’s a machine, some kind of infrastructure, equipment, a tractor, a conference centre ( ... ) and that’s where this map was, we realised at the end that it had some potential. I added some resources from the region, and then it grew with contributions from [anonymous], who introduced the Tamera supplier network ( … ) people who are not so ideologically oriented towards autonomy but are suppliers of interesting products and services. (Américo, interview, October 18, 2019)

In a region of the country for years prone to the settlement of the neo-rural, the map “was a way to aggregate people with a similar ideological orientation” (Américo, interview, October 18, 2019). As for the inclusion criteria, “there were no criteria, it was whoever was and whoever wanted to give [their data], did. It was completely open to whoever wanted to put new points on the map”. The map is still ongoing today in automatic mode and already has over 18,000 visits (8,000 by the end of 2019), and the mapping has been used as a resource for other projects (Moreira, 2018). As for dreams for the future:

I have a wish that one day this updated mapping could be the basis of a kind of community app, Waze-style or others that are linked to traffic, but that would really serve for direct exchange, that people could make purchases and have the rating, a kind of community eBay of the network that would also cater to logistical issues... as mapping has the potential to collect information to develop apps and technology up there that hasn’t happened yet and I don’t know if people from the network would be available for that. (Américo, interview, October 18, 2019)

4.4. SUSY

SUSY - SUStainable and Solidarity Economy map stemmed from the international project Social & Solidarity Economy as Development Approach for Sustainability in and After the European Year of Development 2015 (Troisi et al., 2017)4. Between 2015 and 2017, the project supported by the European Union brought together a network of 26 associations in 23 European countries and nine countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia. In Portugal, the partner organisation was the Instituto Marquês de Valle Flor, a non-governmental organisation for development, supported by Instituto Camões.

With the aim of “increasing the visibility of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Europe and the world”, SUSY’s mission was “to show and strengthen the alternative economy movement, in which social and sustainability principles different from those of the current economic system are applied” (SUSY, n.d., para. 3). According to the project’s website:

people involved and interested in solidarity-based initiatives can network and interact, and we can share and open up the idea of the solidarity economy to more and more people. By collecting and sharing these examples, we aim to gain new insights into the solidarity economy. ( ... ) At the same time ( ... ) we are building links with political decision makers so to increase their support for an alternative way of doing things. (socioeco.org, n.d., para. 1)

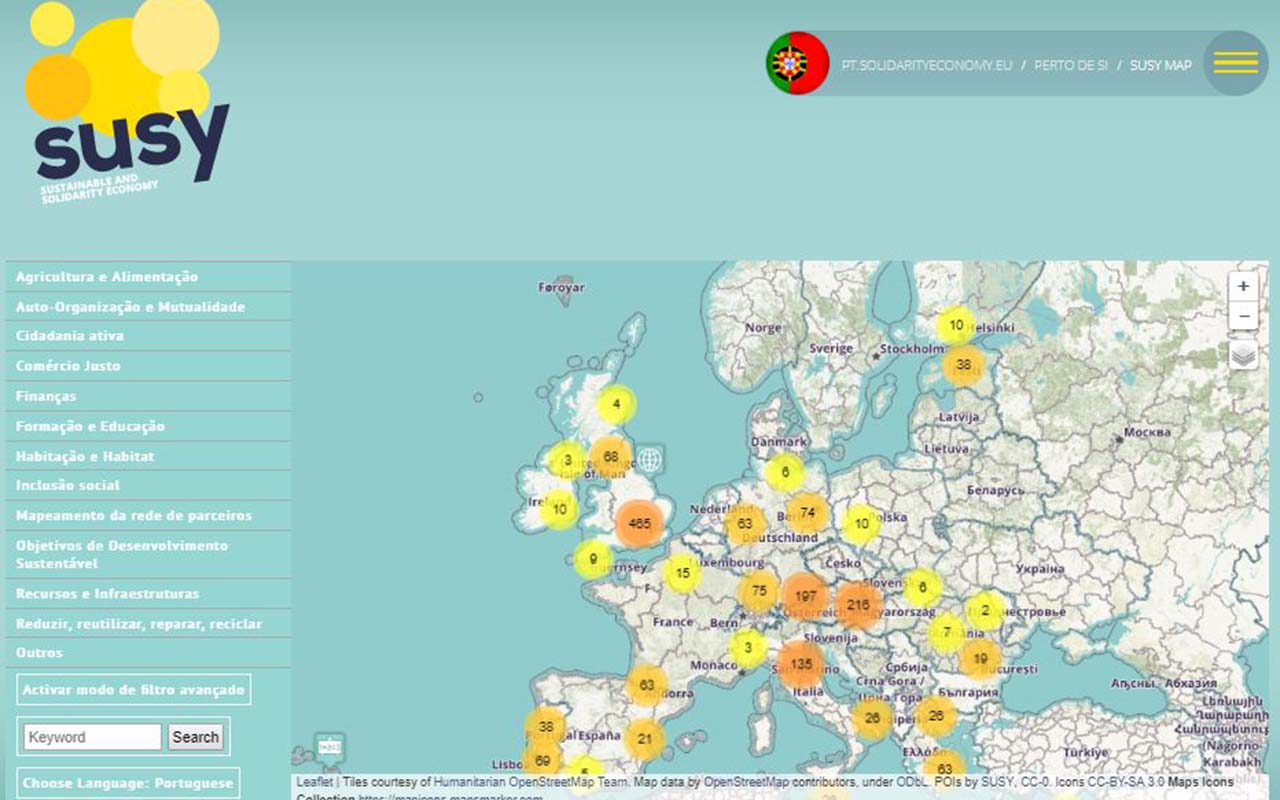

The map showed more than 1,100 practices in the different territories (see Figure 6), distributed by 12 main categories referring to activity sectors, all with pre-defined types of initiatives (see Figure 7). In Portugal, 98 initiatives were mapped, mainly in Lisbon and Alentejo. The first upload was made from the update of a database on the social economy in Portugal made available by the Universidade Católica Portuguesa.

From SUSY, by SUSY - Sustainable and Solidarity Economy, n.d. (http://pt.solidarityeconomy.eu/)

Figure 6 Screenshot of SUSY map showing the European continent

Some initiatives are difficult to put into a box because we are limited to a series of categories, and we doubt ( ... ) because maybe it does not translate the true essence. Then there are citizens’ initiatives ( ... ) that are not formal in their genesis and that we could not include because we needed one contact, and it is a shame because that is how it is, but those were the principles communicated to us within the project. (Ofélia, interview, October 10, 2019)

The map was developed on the Open Street Maps platform in partnership with the international collective TransforMap5:

we wanted whoever was responsible for building this platform also to be a cooperative, an organisation based on social and solidarity economy, to be coherent with the objective of the process ( ... ). Working with a collective was a great challenge and a great source of learning because they are different forms of collaboration; the response timings and the level of commitment are also different when it comes to more hierarchical structures because the people [who] circulate within these collectives ( ... ) will bounce between projects and it was one of the moments that caused the most clash between different partners. There were many technical problems underlying the mapping application. On the other hand, in terms of human resources, lack of response to these problems due to the rotation of people. (Ofélia, interview, October 10, 2019)

Frustration shared by one of the elements of TransforMap:

with great regret, but we could not make the TransforMap project, on which the SUSY map is based, work in the long run, mainly due to ideological and personal differences and also because of the inability to generate livelihoods doing this work and the need for each contributor to organise their life. (Wim, electronic communication, October 22, 2019)

The project also involved the “exchange of practices and experiences” and moments such as the “speakers tour”, with people invited from various continents to visit social and solidarity economy initiatives in Europe. “This proximity between people is an added value” (Ofélia, interview, October 10, 2019).

Giving visibility to initiatives and attempting to strengthen the European SSE [European Social Survey] movement. Serving among peers. Which partners work on the issue of energy or community forestry in Portugal? With access to the map, you could find counterparts... [the map] could be a catalyst in that sense, to make known and share. (Ofélia, interview, October 10, 2019)

As this is a large-scale funded project and with resources allocated for a limited time, one of the main challenges posed was to maintain it: “the lifespan turns out to be limited”. This fear has been confirmed as the mapping is no longer available.

4.5. Transição Portugal

The Transição Portugal network aggregates people and initiatives connected to the transition movement and has the mission to “act as a catalyst, a driver or just an invitation... to create more resilient local communities with a healthy human culture” (Transição Portugal, n.d.-c, para. 1). Acknowledged as a national hub by the international Transition Network movement since the end of 2020, the Portuguese network was initiated in 20106, and developed in the first years, several activities, and then went into a period of dormancy, until its reactivation in 2021-2022.

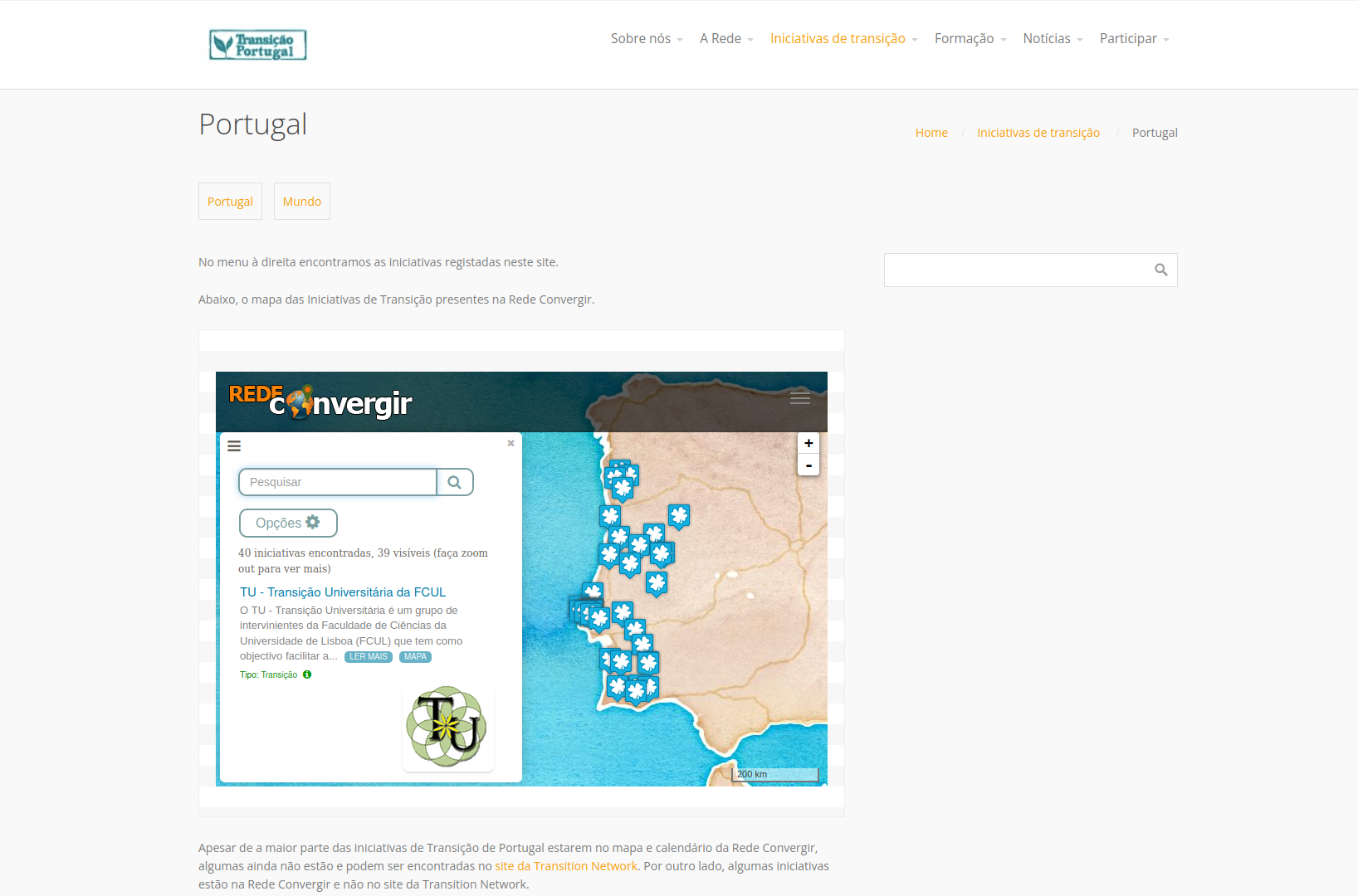

Transição does not have its own mapping and uses two maps provided by external platforms (Rede Convergir and the Transition Network), as they explain on their website:

although most of Portugal’s Transição initiatives are on the Rede Convergir map and calendar, some are not yet and can be found on the Transition Network website. On the other hand, some initiatives are in the Rede Convergir and not on the Transition Network website. (Transição Portugal, n.d.-b, para. 3)

Thus, it is possible to consult on the Transição website (Figure 8) an exported map (automatically updated) from the category “Transição” on the Rede Convergir (with 40 points), referring to social initiatives that facilitate the transition of the community towards a positive vision.

From Portugal, by Transição Portugal, n.d.-b (https://www.transicaoportugal.net/iniciativas-de-transicao/portugal/)

Figure 8 Screenshot of the map available on the Transição Portugal website (March 2023)

On the other hand, the Transição website also provides a link that directs to the mapping page of the Transition Network (Figure 9), in which 22 local transition groups in Portugal, four individual trainers and the national hub are represented. Anyone can propose a new group, hub or trainer on the Transition Network map by registering as an individual.

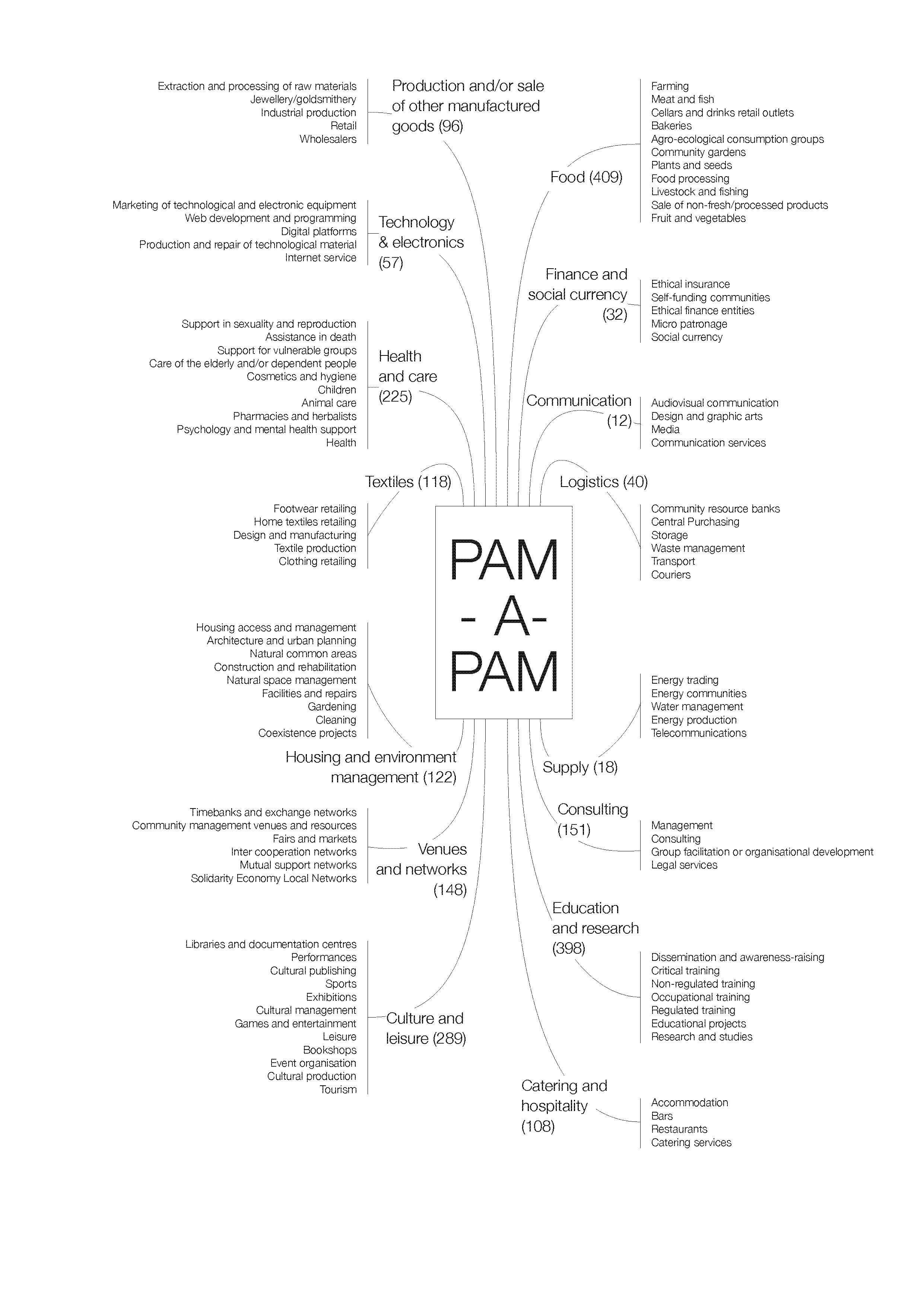

5. The Case of Catalan Pam a Pam

Pam a Pam is the reference map of the solidarity economy in Catalonia (see Figure 10). Created in 2013 on the initiative of the non-governmental organisation Setem (funded by Barcelona City Council) and later with the support of the Xarxa d’Economia Solidària, Pam a Pam defines itself as a “collective tool that contributes to social transformation to overcome capitalist logic”. Moreover, as a “reference platform for the visibility and articulation of the solidarity economy” and a “learning community through activism, training and the practice of responsible consumption” (information available in https://pamapam.org/ca/).

Pam a Pam website (https://pamapam.org/ca/)

Figure 10 Screenshot of the Pam a Pam website (March 2023)

The aim of the map is twofold, according to the Pam a Pam website:

on the one hand, it aims to give visibility to citizenship alternatives and, on the other, to articulate the territory’s solidarity economy initiatives, to get to know them better and learn how we can work together to consolidate a socio-economic movement that is an alternative to capitalism.

With over 1,300 georeferenced initiatives spread across 15 economic activity sectors and 98 subcategories (listed in Figure 11), the map serves as a guide to responsible consumption.

Where can I find clothes made without labour exploitation? Where can I buy organic and fair-trade food? How can I cover the needs of my daily life (housing, education, leisure, etc.) outside the capitalist market? ( ... ) An ever-increasing number of alternatives offer local products, letting us invest our money in a bank consistent with our values, allowing the supply of green and renewable energy to the house, a more communal life, etc. Pam a Pam brings you closer to all these initiatives. (Pam a Pam: Iniciativas de Consumo Responsable y de Economía Solidaria en Cataluña, 2014, para. 1)

Pam a Pam features each initiative according to a list of 15 criteria considered fundamental in the context of the solidarity economy: “proximity”, “fair-trade”, “social integration”, “transparency”, “inter cooperation”, “sustainability”, “waste management”, “energy efficiency”, “salary range”, “personal development”, “gender equity”, “internal democracy”, “ethical banking”, “networks” and “open licences”. To do this, a community of volunteers, known as “xinxetes” (pins), interview the initiatives that want to be part of the mapping and apply a questionnaire to validate their fit with the criteria of the solidarity economy (they must meet at least half of the criteria plus 1). Despite the call for participation in periodic member assemblies and the mapping itself, evident in Pam a Pam’s various communication channels, according to Fuster Morell and Espelt (2018), and also our own observations, there are difficulties in maintaining the mobilisation of territorial communities, for which there was initial European funding. The project seeks to revitalise this front and its economic sustainability model to be more independent of organisations and funders.

Further mappings derived from the original map, such as the local food networks map, the einateca agroecològica7, launched in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, the community economies map (Pam a Pam, n.d.-a), launched in June 2021, aggregating different economic practices that seek to solve needs collectively, as well as regional maps (Pam a Pam, n.d.-c) of the Basque Country and the Valencian Community.

Besides the online platform, Pam a Pam makes itself visible through event participation, offering promotional materials (calendars, postcards, information leaflets) and a sticker identifying the initiatives on the map to be used in physical spaces, showing that “this is a Pam a Pam initiative”.

6. Summary and Final Considerations

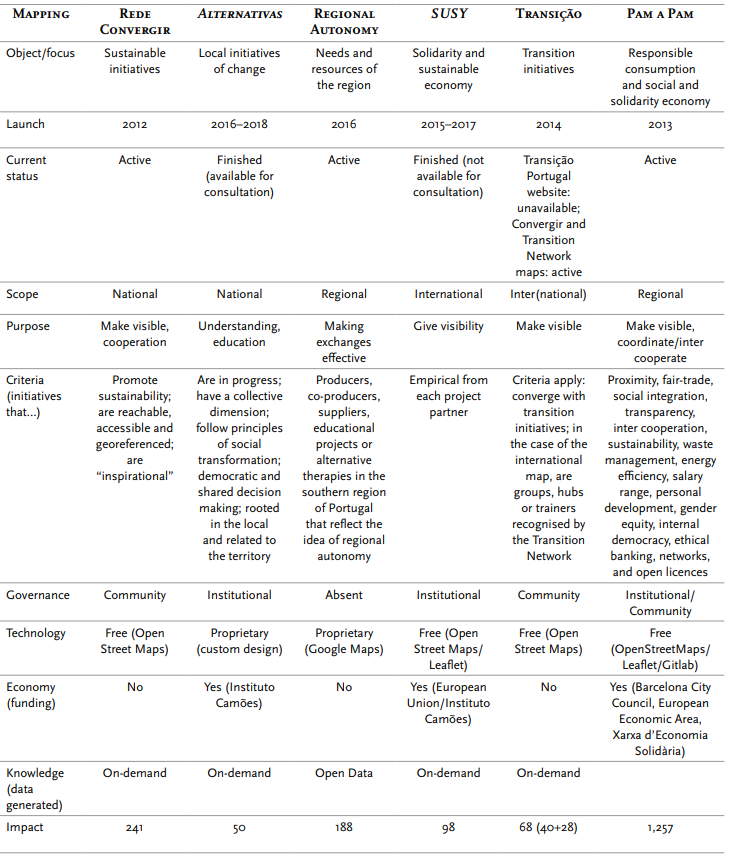

The maps studied highlight different approaches to the collaborative mapping of alternative economies. We summarise the evidence in Table 1, considering the pro-common democratic qualities proposed by Fuster Morell (2018).

Table 1 Summary of the analysis results of five maps of alternatives in Portugal and one Catalan map

Pursuing the objective of studying the potential of maps as a meta-territory/good/ commons, we then pour the results - both those summarised in the table and those collected in interviews - into the following considerations and extensions.

6.1. Governance

We recognise, in the maps studied, both institutional and community contexts, as well as distinct mechanisms of participation by members.

By exceptionally classifying the Regional Autonomy case as “absent”, we acknowledge the impossibility of identifying a clear “tutelage” or signature of authorship, affiliation and/or control even if this map remains active and in apparent growth. Such an idea is harmonious with the underlying aspirations of these initiatives.

The “mechanisms for member participation” exist. However, they are challenged by poor technological literacy and a lack of a key resource: the recognition by participants of real interest (see the economics section below).

Although the initiatives studied are linked by similar ideological convictions, we can observe more cases where such initiatives ignore each other than where they cooperate.

Depending on their size/ambition, the mapping initiatives draw closer to practices contrary to the aspirations expressed, namely regarding the abuse of the inclusion/exclusion rules, the opacity of the decision-making processes, and (in)dependence on opposing external forces such as technologies and funding systems.

Nevertheless, the need and usefulness of mapping and understanding how to do it is acknowledged among those involved.

Key question: how to centralise information while decentralising power?

6.2. Economy

The mappings are all reportedly not-for-profit. We did not collect information regarding the transparency of existing financial flows in these projects. It seems useful to us, however, to make a broader reading of the economy here:

The stakeholders in these initiatives are often driven by a mixture of a need for existential fulfilment and expectations of individual livelihood and soon realise that the response to such aspirations is fragile and/or ephemeral.

When mapping initiatives to obtain funding and commit themselves to the parameters of the calls for which they are aiming, they find it difficult to harmonise these parameters with the incidences of the process and the changes they require. On the other hand, these institutional commitments never guarantee a solution to the problem of the maintenance/longevity of the initiatives.

There is an invisible guardianship, which we can name as endogenous and exogenous socio-political-cultural contexts for these initiatives. One navigates, it is suggested, in a dilemma between the aspirations for autonomy and the constant need to return, even if partially or temporarily, to the system one wants to leave.

Understanding the economy as the management of resources aiming at viability for life, we propose that resources are: the individual and group energies generated by the need for an alternative; the effective production capabilities that these individuals and groups have; the ability, while staying on course, to attract and dialogue with resources outside the restricted circles of the initiatives.

Key question: how to assure financial independence and human availability?

6.3. Technology

The use of digital technology is a clear example of what we stated in the previous point. We argue:

“Capitalist” mapping technology platforms impose a technical/infrastructural pattern that is difficult to counter. We must recognise that such globalised and globalising platforms impose themselves through their ubiquity and supposed ease of access and use.

We know from various fields, from information technology to medicine and mechanics, that the sophistication of technology prevents access to tools. In this case, the globalising tools are only apparently a gift and facilitation. In fact, the pattern they impose tends towards hegemony and the suppression of autonomy.

The opacity and domination inherent in the sophistication of technology can only be countered by experimental use (Flusser, 1998).

The people and groups who embody these maps are confronted with their illiteracy and dependence on digital technologies, which they feel are inevitable.

In this sense, the recourse to free software and decentralised architectures is controversial, as it implies a harder handling of the illiteracy and/or dependence already instigated by globalising platforms.

Key question: how to adopt practical tools in line with the principles?

6.4. Knowledge

Regarding the knowledge generated by the different mappings, we make some comments around their categorisation, legibility and openness:

The need to transfigure to understand or create truth is called “categorisation” or “taxonomy”. Part of the vice imposed by the socio-political-cultural context mentioned above concerns the need to separate into watertight boxes complex, dynamic, promiscuous, unclassifiable realities.

The lexical diversity we observe in the “criteria” line of Table 1 is an advantage since it makes it difficult for the capitalist world to cannibalise lexical motifs, as is their practice and lore. Nevertheless, the table displays many terms already appropriated and trivialised by the supposedly fracturing causes of the dominant powers.

In this sense, stating that these maps wish to propose and propagate deviations from the clear majority does not mean that they benefit from, let us say, easy general readability.

Key question: how to unlock data and knowledge and at the same time keep the integrity of the initiative?

6.5. Impact

In terms of impact, the difficulty in quantifying or measuring the reach of initiatives beyond the obvious number of projects mapped stands out.

The stakeholders struggle to keep the platforms alive, so little can be expected from a critical and systematic self-observation that could highlight impacts (or the lack of them).

Impact measures will, in formally funded projects, be required by funders on terms unknown to us. Non-formal impact measures are non-existent, bringing us back to this list’s first point. How does one have the stamina to do it all?

Key question: how to critically and sustainably measure these instruments?

6.6. The Catalan Example

While not immune to problems that overshadow different mappings, the Catalan example points to possible ways forward. It has created a governance structure led by Catalonia’s solidarity economy network, Xarxa d’Economia Solidària, but also decentralised and open, with frequent assemblies and local teams spread across the territory that ensure local rooting, the integrity of the points, and updating the map. It has obtained initial financial support for technological development and the creation of territorial teams. Annually, Xarxa d’Economia Solidària dedicates around €65,000 of its budget to Pam a Pam (Xarxa d’Economia Solidària de Catalunya, 2019, 2020) while looking for autonomous forms of economic sustenance (Fuster Morell & Espelt, 2018). It has developed a platform based on free and open-source software. It makes all the code freely available on GitLab for replication and improvements, where a digital community of programmers operates. As for impact, data such as the map’s usefulness in identifying producers and suppliers and gaining new customers or contracts are being collected through a survey to measure the impact on the mapped initiatives (XES, 2022).

7. Conclusions

The studied maps testify to the fragility and ephemerality of the “diverse universes” in Portugal. Here, keeping the mappings alive - like other deviant initiatives - depends essentially on a mobilising force comparable to what feminists define as reproductive work necessary for the maintenance of life (Federici, 2018). Nevertheless, the study reiterates both the importance of maps as communicative devices and promoters of the realities they aim to map and the need to make alternative economic practices diverging from the dominant capitalist model visible.

The study contributes to the disciplinary intersection between collaborative mappings, digital commons and diverse economies, encouraging the debate, their practice, and dissemination in the territories. We hope the contribution can inspire new advances in mapping solidarity economy initiatives in Portugal to nurture the divergent and real alternatives of consumption, production, and distribution available in the territory.

We also believe we contribute to inscribing the diverse communication and communication design economies. It is about more than just the qualities and challenges involved in communication objects and structures. It is about nurturing alternative ways of life. In fact, the maturity observed in the Catalan case was also achieved thanks to the professionals and researchers in these areas who invested their work and their livelihood in this kind of social drift through a dominant socio-economic fabric that underestimates and systematically preys not on the substance but on the communication power of alternatives.

The map is not the territory, and practices do not exist because they are on the map. The 1:1 scale map ironically evoked by Jorge Luis Borges probably exists idealistically, scratched on the heels, in the eyes, in the ears and in the noses of those who travel the territory. This may be where the utopia - by nature unattainable, but meta-mapping - that can guide the work of mapping what is diverse is to be found.

Acknowledgements

The work conducted by the first author was funded by national funds through the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under a PhD grant with the reference SFRH/BD/136809/2018. We thank the peer reviewers, Professor Cristina Parente for her reading and critical comments on the paper and the conference “Social Solidarity Economy and the Commons: Contributions to the Deepening of Democracy” (ISCTEIUL, 2019) for the opportunity to present and discuss a preliminary version of the paper in a poster.

REFERENCES

Adrien. (2017a, 6 de janeiro). Geographies of alternatives: Atlases of maps. Metamaps. https://metamaps.cc/ maps/1979 [ Links ]

Adrien. (2017b, 8 de março). Transformap(s) ecosystem. Metamaps. https://metamaps.cc/maps/1938 [ Links ]

Alternativas. (s.d.-a). Como foi feito. Retirado a 8 de março de 2023 de https://www.projetoalternativas.org/ como-foi-feito [ Links ]

Alternativas. (s.d.-b). Mapa de iniciativas. Retirado a 8 de março de 2023 de https://www.projetoalternativas.org/mapa-de-iniciativas/ [ Links ]

Balsa, C. M., Albuquerque, C., Avelar, D., Lopes, G. P., Nolasco, M., Santos, P., & Rocha, S. (2016). Experimentação socioecológica: Novos caminhos para a participação no desenvolvimento local sustentável e integral. Relatório científico do projeto de investigação CATALISE - Capacitar para a Transição Local e Inovação Social. BASE; Comissão Europeia; FCT. [ Links ]

Baumgarten, B. (2017). Back to solidarity-based living? The economic crisis and the development of alternative projects in Portugal. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 10(1), 169-192. https://doi.org/10.1285/I20356609V10I1P169 [ Links ]

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Borowiak, C. (2015). Mapping social and solidarity economy: The local and translocal evolution of a concept. In N. Pun, B. H.-b. Ku, H. Yan, & A. Koo (Eds.), Social economy in China and the world (pp. 17-40). Routledge. [ Links ]

Castells, M., Banet-Weiser, S., Hlebik, S., Kallis, G., Pink, S., Seale, K., Servon, L. J., Swartz, L., & Varvarousis, A. (2017). Another economy is possible: Culture and economy in a time of crisis. polity. [ Links ]

Conill, J., Castells, M., Cardenas, A., & Servon, L. (2012). Beyond the crisis: The emergence of alternative economic practices. In M. Castells, J. Caraca, & G. Cardoso (Eds.), Aftermath: The cultures of the economic crisis (pp. 210-248). Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Drake, L. (2020). Visualizing and analysing diverse economies with GIS: A resource for performative research. In J. K. Gibson-Graham & K. Dombroski (Eds.), The handbook of diverse economies (pp. 493-501). Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Espelt, R., Peña-López, I., Miralbell, O., Martín, T., & Vega, N. (2019). Impact of information and communication technologies in agroecological cooperativism in Catalonia. Agricultural Economics, 65(2), 59-66. https://doi.org/10.17221/171/2018-AGRICECON [ Links ]

Federici, S. (2018). Marx and feminism. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 16(2), 468-475. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i2.1004 [ Links ]

Ferreira, S., & Almeida, J. (2021). Social enterprise in Portugal: Concepts, contexts and models. In J. Defourny & M. Nyssens (Eds.), Social enterprise in Western Europe. Theory, models and practice (pp. 182-199). Routledge. [ Links ]

Flusser, V. (1998). Ensaio sobre a fotografia - Para uma filosofia da técnica. Relógio d’Água. [ Links ]

Fuster Morell, M. (2018). Qualities of the different models of platforms. In M. Fuster Morell (Ed.), Sharing Cities: A worldwide cities overview on platform economy policies with a focus on Barcelona (pp. 125-158). Sehen. [ Links ]

Fuster Morell, M., & Espelt, R. (2018). A framework for assessing democratic qualities in collaborative economy platforms: Analysis of 10 cases in Barcelona. Urban Science, 2(3), Artigo 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2030061 [ Links ]

Fuster Morell, M., & Espelt, R. (2019). A framework to assess the sustainability of platform economy: The case of Barcelona ecosystem. Sustainability, 11(22), Artigo 6450. [ Links ]

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2008). Diverse economies: Performative practices for “other worlds”. Progress in Human Geography, 32(5), 613-632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508090821 [ Links ]

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2020). Reading for economic difference. In J. K. Gibson-Graham & K. Dombroski (Eds.), The handbook of diverse economies (pp. 476-485). Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Google Maps. (s.d.). [Mapeamento de necessidades e recursos da região, iniciado no encontro de comunidades em Tamera, 15-16 Abril 2016. Desde então tem sido actualizada permanentemente por todos os que se dedicam a isto. / Mapping of the needs, resources and means of the region, started in the gathering of Communities in Tamera, 15-16 April 2016. It has been since then updated permanently by everyone engaging on it]. Retirado a 7 de abril de 2023 de https://www.google.com/maps/d/edit?mid =1dJNKfWnefR12uDPQpTPCymfdlSA&usp=sharing [ Links ]

Guerreiro, M. (2013). Contributo para o mapeamento de iniciativas de economia solidária na área metropolitana de Lisboa [Dissertação de mestrado, Instituto Universitário Lisboa]. Repositório do Iscte. http://hdl.handle.net/10071/6877 [ Links ]

Helfrich, S. (2016, 25 de setembro). Mapping as commons. CommonsBlog. https://commons.blog/2016/09/25/mapping-as-a-commons/ [ Links ]

Hespanha, P., Santos, L. L. dos, Silva, B. C. da, & Quiñonez, E. (2015). Mapeando as iniciativas de economia solidária em Portugal: Algumas considerações teóricas e práticas. In B. de S. Santos & T. Cunha (Eds.), Colóquio internacional epistemologias do sul: Aprendizagens globais sul-sul, sul-norte e norte-sul - Actas (Vol. 3; pp. 465-475). Centro de Estudos Sociais. [ Links ]

Labaeye, A. (2017). Collaboratively mapping alternative economies. Netcom, (31-1/2), 99-128. https://doi.org/10.4000/netcom.2647 [ Links ]

Moreira, S. (2018, 25 de setembro). CooperAcção ao sul de Portugal: Ecos de uma rede de redes em germinação. Mapa. http://www.jornalmapa.pt/2018/09/25/cooperaccao-ao-sul-de-portugal/ [ Links ]

Mourato, J. M., & Bussler, A. (2019). Community-based initiatives and the politicization gap in socioecological transitions: Lessons from Portugal. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 33, 268-281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.08.001 [ Links ]

Nogueira, C. (2018). Contornos e tendências das comunidades sustentáveis intencionais em Portugal - Uma análise descritiva e exploratória. Chão Urbano, 6, 11-39. [ Links ]

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press. [ Links ]

Pam a Pam. (s.d.-a). Economies comunitàries. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de https://pamapam.org/ca/ economies-comunitaries/ [ Links ]

Pam a Pam. (s.d.-b). Einateca agroecològica. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de https://pamapam.org/ca/einateca/ [ Links ]

Pam a Pam. (s.d.-c). Mapes agermanats. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de https://pamapam.org/ca/mapes-agermanats/ [ Links ]

Pam a Pam: Iniciativas de consumo responsable y de economía solidaria en Cataluña. (2014, 29 de dezembro). Plataforma de ONG de Acción Social. https://www.plataformaong.org/noticias/623/ pam-a-pam-iniciativas-de-consumo-responsable-y-de-economia-solidaria-en-cataluna [ Links ]

Rede Convergir. (s.d.-a). Mapa das iniciativas. Retirado a 8 de março de 2023 de https://redeconvergir.net/iniciativas [ Links ]

Rede Convergir. (s.d.-b). Sobre. Retirado a 17 de outubro de 2019 de https://redeconvergir.net/sobre [ Links ]

Safri, M., Healy, S., Borowiak, C., & Pavlovskaya, M. (2017). Putting the solidarity economy on the map. The Journal of Design Strategies, 9, 71-83. [ Links ]

Soares, M. C. (2017). Prefigurative politics and emergent communitarian spaces: The case of Portugal. Santiago, 144, 519-533. http://hdl.handle.net/10316/43720 [ Links ]

Social Business School & Instituto Padre António Vieira . (2015). Mapa de inovação e empreendedorismo social - 1ª fase: Norte, Centro e Alentejo. IES; IPAV. [ Links ]

socioeco.org. (s.d.). Sustainable and solidarity economy (SUSY). Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de https:// socioeco.org/bdf_organisme-797_pt.html [ Links ]

SUSY. (s.d.). SUSY - Sustainable and Solidarity Economy. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de http://pt.solidarityeconomy.eu/ [ Links ]

TransforMap. (s.d.). About. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de http://transformap.co/about/ [ Links ]

Transição Portugal. (s.d.-a). A nossa história. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de https://www.transicaoportugal.net/sobre-nos/a-nossa-historia/ [ Links ]

Transição Portugal. (s.d.-b). Portugal. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de https://www.transicaoportugal.net/iniciativas-de-transicao/portugal/ [ Links ]

Transição Portugal. (s.d.-c). O que é a Transição. Retirado a 22 de janeiro de 2023 de https://www.transicaoportugal.net/sobre-nos/o-que-e-a-transicao/ [ Links ]

Troisi, R., di Sisto, M., & Castagnola, A. (Eds.). (2017). Análise final da investigação SSEDAS. A economia transformadora: Desafios e limites da economia social e solidária (ESS) em 55 territórios na Europa e no mundo (versão resumida). https://ened-portugal.pt/site/public/paginas/estudos-e-investigacoes-pt-2.pdf [ Links ]

Valentim, I. (2012). Economia solidária em Portugal: Inspirações cartográficas. Editora Mó de Vida. [ Links ]

Xarxa d’Economia Solidària de Catalunya. (2019). Memòria 2019. https://xes.cat/wp-content/ uploads/2020/05/MEMORIA_XES2019.pdf [ Links ]

Xarxa d’Economia Solidària de Catalunya. (2020). Memòria 2020. https://xes.cat/2021/09/16/ja-disponible-la-memoria-de-la-xes-2020/ [ Links ]

XES. (2022, 4 de outubro). 3 minuts per Pam a Pam. https://xes.cat/2022/10/04/3-minuts-per-pam-a-pam/ [ Links ]

1In 2023, the collective seems to be no longer active, but the project website is still available at http://transformap.co/. A series of “meta mappings” of the TransforMap actors and ecosystem was created by Adrien Labaye in 2016 and is available at MetaMaps (Adrien, 2017a, 2017b).

3The project website provides a background to the process, which was first designed in 2013, but only had funding approved in 2016.

4This and other SUSY project resources (such as videos and project reports) are available at socioeco.org (n.d.).

55. All the project data was available for download at https://data.transformap.co/place/name under a public domain license and in GeoJSON format.

66. The Transição Portugal website gives a brief history acknowledging the seminal role in 2009 of the social network Transição e Permacultura em Portugal, based on the Ning platform: “it operated as the first aggregator of stakeholders in the movement, bringing together simultaneously (and above all) those interested in the permaculture movement” (Transição Portugal, n.d.-a, para. 22). Years later, the network was appropriated by one of its members, who eventually changed its identity to the Rede EBC - Economia para Bem-Comum, with a markedly neoliberal slant.

7The einateca agroecològica is a platform that serves as an agroecological “tool library” (https://einatecagroecologica.pamapam.org/; Pam a Pam, n.d.-b).

Received: December 11, 2022; Accepted: March 08, 2023

texto en

texto en