Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.43 Braga jun. 2023 Epub 30-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.43(2023).4455

Thematic Articles

The Importance of Communication Design in the Process of Disseminating Community Practices in Social Neighbourhoods: The Balteiro

i Instituto de Investigação em Design Media e Cultura, Escola Superior de Design, Instituto Politécnico do Cávado e do Ave, Barcelos, Portugal

ii Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

iii Unexpected Media Lab, Faculdade de Belas Artes, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

iv School of Architecture and the Built Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden

v Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden

No presente artigo pretende-se demonstrar de que modo a investigação em design de comunicação pode contribuir para a disseminação de práticas comunitárias em contextos economicamente desfavorecidos, como é o caso dos bairros sociais. Este estudo surge no âmbito do projeto de investigação ECHO, onde a principal missão é conhecer e documentar duas práticas comunitárias auto-iniciadas no bairro social do Balteiro, em Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, com o objetivo de as divulgar e estimular a sua replicação em contextos sociais análogos. Começa-se por apresentar uma revisão de literatura sobre o papel do design ao serviço das comunidades, focada, em particular, nos conceitos de design social e do design universal, que fundamenta a relevância e pertinência da problemática estudada. De seguida, descreve-se o caso de estudo do Balteiro. Apresentam-se as metodologias adotadas nesta investigação, nomeadamente, o conjunto de entrevistas realizadas com o objetivo de conhecer a história das duas práticas comunitárias, e que serviram de base ao desenvolvimento de um estudo prévio para uma plataforma online e um conjunto de documentários. Este estudo comprovou a importância do envolvimento dos designers neste processo de disseminação, em equipas que deverão ser multidisciplinares. O trabalho de investigação no terreno deve ser próximo da comunidade, das instituições e dos diferentes atores sociais envolvidos, de forma a compreender a complexidade do contexto de estudo e definir o modo de atuação do design. A experiência empírica adquirida com este estudo demonstrou que o trabalho na área social deve ser desenvolvido a nível local, focado em pequenas comunidades ou organizações informais, com a consciência de que os resultados se atingem de forma lenta e gradual.

Palavras-chave: design de comunicação; práticas comunitárias; bairros sociais; design social; design universal

This article aims to demonstrate how research in communication design can contribute to disseminating community practices in economically disadvantaged contexts, such as in social housing neighbourhoods. This study stems from the ECHO research project, where the main mission is to understand and document two self-initiated community practices in the social housing neighbourhood of Balteiro, in Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, to disseminate them and foster their replication in similar social contexts. It begins with a literature review on the role of design on behalf of communities, focusing, in particular, on the concepts of social design and universal design, which substantiate the relevance and pertinence of the issue under study. Then, it describes the case study of Balteiro. It presents the methodologies adopted in this research, namely the interviews conducted to learn about the history of the two community practices. This provided the basis for developing a preliminary study for an online platform and a series of documentary films. This study proved the importance of involving designers in this dissemination process through multidisciplinary teams. The research work in the field should be close to the community, the institutions and the different social actors involved to understand the complexity of the study context and define how design should operate. The empirical experience from this study has shown that work in the social area should be developed locally, focused on small communities or informal organisations, and aware that results are achieved slowly and gradually.

Keywords: communication design; community practices; social housing neighbourhoods; social design; universal design

1. Introduction

This study is part of the exploratory research project Echoing the Communal Self (ECHO). Its main mission is to understand and document self-initiated community practices in disadvantaged social contexts to disseminate them and foster their replication in similar contexts. Based on preliminary work done with the Municipality of Vila Nova de Gaia (VNG), Gaiurb’s social workers1, and residents’ associations, two relevant community initiatives were identified, namely: the Associação Recreativa Clube Balteiro Jovem and the Escola Oficina (EO), both stemming from the Balteiro social housing neighbourhood2. Despite these initiatives contributions to the inclusion and harmonisation of the social fabric, the Municipality of VNG identified challenges in their mediation and expansion.

Traditionally, doing these community practices known beyond their geographical territory is challenging. Scaling up beyond these local boundaries could stimulate and inspire other communities willing to implement similar practices. This could happen both in the VNG municipality itself and nationally and even internationally.

We argue that design can make an important contribution by developing communication and pedagogical strategies that amplify these relevant, citizen-led practices. In order to address this challenge, the ECHO project brought together a team of researchers from communication design, digital media design, documentary photography and video, information design, illustration, psychology and ethnography.

As part of the ECHO project, this paper focuses on the study of the contribution of communication design to disseminating these practices. It includes creating an online platform and a documentary film about each practice (to be developed in the project’s next phase). It begins with a literature review on the role of design on behalf of communities, substantiating the relevance and pertinence of the issue under study. This section addresses authors such as Tromp and Vial (2022) and Nold et al. (2022), who reflect on such topics as the contribution of social design and universal design in society, highlighting the complexity of projects with multiple stakeholders.

The ECHO project is then presented, providing the background for the issue and the case study of Balteiro, linking it to the methodologies adopted. This section begins with a brief history of the two community practices selected, based on the information collected, particularly a series of interviews conducted in the field, essential for understanding the role of design in this project.

Lastly, the preliminary study for creating the online platform and the documentary films is presented.

2. Social Design and Universal Design: From Theory to Practice

Design is evolving and developing different interactions with society. Recently, different areas, namely design, have shown interest in creating change in the social collective, seeking to implement real changes in society (Shea, 2012; Shirky, 2010; Simmons, 2011). This section will provide a literature review on the role of design for the benefit of society, explaining how it has evolved. It starts with an overview of the historical evolution of social design, followed by a definition of universal design and its comparison with inclusive design.

Social design is currently intertwined to create impact and change in society. Due to its theoretical and practical interdisciplinary nature, many authors refrain from proposing a definitive definition for the concept (Tromp & Vial, 2022). Social design is a field that is still evolving and being developed. Nold et al. (2022) have proposed structures and starting points to initiate an academic debate on the definition of this area. According to Tromp and Vial (2022), the objective of this field of study has remained consistent. However, its progression is linked to the techniques employed and the designer’s emphasis, as evidenced by the discipline’s past.

In 1947, László Moholy-Nagy coined the term “social design” to describe the designer’s social and moral obligation towards society. During the 1950s to the 1970s, various authors, including Erskine (1968), Jacobs (1961), Mollison (1988), Papanek (1972) and Schumacher (1973) suggested that designers should reject the notion of design solely as a means of generating profit. According to Papanek (1972), design should be innovative, creative, and multidisciplinary while also addressing the needs of humans. The author expresses his disapproval of making a profit from the needs of others. Papanek explains that producing a therapeutic toy for amputee children should not be delayed for months while waiting for patent approval (Armstrong et al., 2014; Kuure, 2017). According to Margolin and Margolin (2002), the social and market design models are not opposing forces but rather represent opposite ends of a spectrum. The distinction is based on the goals and priorities of the project rather than the methods or distribution used. The author argues that social design is present in the consumerist sphere because it addresses social needs that the market fails to fulfil. The social design highlights the problems and risks faced by vulnerable members of society who do not fit into the common consumer group. This includes individuals with low incomes, age-related problems, health issues, and other restrictions. The goal is to involve those affected in addressing these issues. Building upon De Carlo’s (2005) argument regarding the student movements of 1969, we can extend this idea to architecture and posit that design should not be left solely in the hands of designers. Instead, the involvement of the target user in the design process is crucial.

Much later, authors like Simmons (2011) raise concerns about this approach. They fear that these designers are so focused on avoiding the market that their projects lose sight of the impact of their projects on society. To explain the purpose of his book about designing for social causes, Simmons (2011) states, “whether for the greater good or greater profit, it’s all just design” (p. 4). Over the years, certain designers have taken an activist approach to their work, aiming to empower individuals and social institutions through their designs (Tromp & Vial, 2022). According to Margolin and Margolin (2002), designers should collaborate with professionals in various fields like health, education, social work, and crime prevention. They also highlighted the importance of designers studying and comprehending social needs. Numerous studies have shown the importance of engaging design in a multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary practice (Hepburn, 2022; Irwin et al., 2015; Sellberg et al., 2021).

Nold et al. (2022) state that social design involves working with people in social situations and collaborating with communities and institutions through various activities and processes. Chen et al. (2016) also highlight social design’s participatory and cocreation nature but warn of the projects’ complexity. Social issues and the communities they affect often emerge from complex political environments and market systems. Many designers find it challenging to understand the impact of these connections on projects. Chen et al. suggest that present-day social design can function on a small scale, such as within communities or informal organisations. According to Koskinen and Hush (2016), some projects have unrealistic expectations, and social design struggles to meet their objectives. These authors propose applying a “molecular” social design within small social universes where contributions can be easily measurable.

Tromp and Vial (2022) propose a framework that provides a clearer understanding of social design. It identifies five key components related to design orientation and direction, namely:

(1) care-driven activities for the wellbeing of underprivileged people, (2) responsiveness-driven activities for good governance, (3) political progressdriven activities for empowered citizens, (4) social capital-driven activities for beneficial communities, and (5) resilience-driven activities for sustainable future systems. (Tromp & Vial, 2022, p. 210)

Social design is a growing field that aims to create positive societal change. It involves collaboration among designers and individuals from various fields, including politics, bureaucracy, and informal social activities (Armstrong et al., 2014). This perspective gives rise to universal design, which aims to promote the natural inclusion of individuals in their daily activities, thus positively impacting society. This area aims to develop solutions that everyone can experience without requiring adjustment to specific individuals or groups (Story, 1998). This field fits into social design because it aims to make society more inclusive and accessible for everyone.

Despite its utopian goal, universal design intends to address the limitations of inclusive design. According to Coleman et al. (2007), there has been a trend in design towards creating solutions that cater to all audiences, possibly driven by commercial interests. As a result, inclusive design became necessary to offer solutions for people with “specific needs”. This area sought to adapt existing design solutions for audiences with specific needs, people with disabilities, and limitations related to age, education or financial resources. Inclusive design is well-intentioned, but these groups with additional needs are often only considered after the project is finished. As a result, solutions are frequently retrofitted, or new versions are made specifically for these groups. In short, what may seem a functional solution may highlight the challenges these groups face.

Instead, universal design underlines the need to develop discreet solutions that cater to all users without highlighting the special needs of any particular group. As such, this field requires all users to be considered from the beginning of the design process. The ECHO project will take a universal design approach to guide the study and design process, involving the entire target audience from the first step towards disseminating the case studies under analysis.

Social design aims to foster a collaborative relationship honouring local customs and traditions. It connects with various places and people, creating synergies and partnerships with common institutions and individuals (Chen et al., 2016). The ECHO project approached and engaged in dialogue with several institutions, including Gaiurb, the municipality, EO, and the Associação Recreativa Clube Balteiro Jovem. The ECHO team interacted with, interviewed, and studied the residents of the Balteiro neighbourhood to establish and enhance strong relationships. This whole process requires multiple considerations. If ECHO designers failed to recognise the significance of listening to all stakeholders, work could have biased readings of the issue studied.

According to Del Gaudio et al. (2016), collaborative design faces various issues concerning the formation of partnerships, power distribution among the parties involved, task delegation, and the actions of each agent. These authors argue that designers must be mindful of various aspects of collaborative design, such as the need for negotiation skills and the possibility of power struggles in partnerships. According to Del Gaudio et al., designers must ensure that their partners clearly understand the working process and how they can contribute. They also highlight that partners may need to be reminded of the design potential. The designer is responsible for motivating their partner and reaching a shared understanding of goals. The authors believe that a designer should be aware of their partners’ political, social, or economic involvement in the project and their interactions with the community. This knowledge will enable the designer to impact society through their work positively.

In order to fully comprehend the topic at hand and the background of this study, we will provide an overview of the social neighbourhood of Balteiro. This will include a brief history of social housing neighbourhoods in Portugal, the economic status of its inhabitants, and the primary challenges they encounter. This will provide insight into how self-initiated community projects are significant to society and why recording and sharing their impact is crucial.

3. The ECHO Project: Issues and the Balteiro Case Study

In Portugal, solving the housing problem became a major priority after the 1974 revolution, particularly in urban areas like Lisbon and Porto (Antunes, 2019). Social housing in Portugal is primarily owned by the public sector. However, the author believes that over the past 50 years of democracy, social housing policies have been developed inconsistently without a long-term strategy, systematisation, or continuity (Antunes, 2019, p. 14). Hence there are still “serious issues concerning the availability of adequate housing” (p. 14). The author draws attention to the plight of over 25,000 families currently living in substandard conditions. Some of these housing problems violate basic human rights, such as “living in unstable neighbourhoods with poorly built houses made of cheap materials and lacking access to electricity, plumbing, sanitation, and public lighting” (Antunes, 2019, pp. 14-15).

Moreover, the 1990s were crucial for public housing development as there was “a strong national resolve to eliminate inhumane living conditions” (Antunes, 2019, p. 14). Currently, public housing makes up only 2% of the total housing available in the country and is home to approximately 2.5% of the Portuguese population.

In the North of the country, in Porto, the most iconic social housing neighbourhoods were built in the late 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s on the city’s outskirts. As urban areas have expanded in recent decades, these neighbourhoods have gradually integrated into the city to a greater or lesser extent (Fernandes & Mata, 2015). For Fernandes and Mata (2015), the peripheral situations of these neighbourhoods today do not strictly “concern physical distance, but mainly social and symbolic distance” (p. 9). Within this interpretation of the relations between urban and individual space, these authors propose the expression “disqualified periphery”, pointing out the fact that these social housing neighbourhoods are spaces that, “in the social debate, are seen and said to contain some element that deviates them from a supposed normality’” (Fernandes & Mata, 2015, p. 2).

Since the 1980s, social housing neighbourhoods experienced high unemployment rates due to intense deindustrialisation. In response, informal economies, particularly those related to the consumption and trafficking of illegal drugs, grew. Social housing neighbourhoods are being redefined as more than just poverty-stricken areas. They are now also associated with criminal activity, creating a perception of danger around them (Fernandes & Mata, 2015). Luís Fernandes (1998) points out that “these neighbourhoods can either be inhabited or avoided” (p. 123). That is a commonly held belief that still prevails regarding most social housing neighbourhoods in large urban centres, especially those heavily covered by the media, due to problems associated with criminality.

Social housing, especially in social housing neighbourhoods, has not succeeded in achieving its inclusivity mission in Portugal. However, as Fernandes and Mata (2015) point out, the “provincialism” and the “insularity” observed in these spaces:

cannot be read as “negative” or “positive”, as they both underlie the development of local identities and the sense of belonging, which help build communities and empower individuals. However, they can also create barriers to overcoming the stigma associated with a challenging environment. (p. 12)

The ECHO project was created by exploring local initiatives that enhance community involvement and promote inclusion. In preliminary fieldwork conducted in the municipality of VNG, the local authority was informed of cases such as the Balteiro neighbourhood (also called “Balteiro development”), which in the past was a tough place, associated with issues such as drug trafficking and consumption. Security and social stability have been restored thanks to a robust infrastructure and supportive rehabilitation. The change helped promote self-initiated community practices, which emerged in the neighbourhood in mid-2015 (Moreira, interview, May 4, 2022; Mota, interview, December 10, 2021).

The community practices have significantly impacted the neighbourhood, but the municipality of VNG acknowledges the need to make them more widely known. These practices promote inclusion, combat stigma, boost personal and collective self-esteem, and contribute to social regeneration. They also have the potential to be replicated in other contexts.

Thus, design research acts as a mediator to understand and record community practices and to explore solutions for promoting their dissemination. Recognising, acknowledging, and systematising these practices will encourage the neighbourhood and its community to be more open to the outside world.

4. Methodology

This section describes the methodologies proposed and adopted by the ECHO project to showcase how communication design can enhance the dissemination of community practices in social housing neighbourhoods. The study focuses on the case of Balteiro.

Before beginning the project, we followed the recommendations of experts like Del Gaudio (2016) and ensured that all necessary conditions were in place for the project to proceed smoothly. This included ensuring that all stakeholders, both individuals and groups, were willing and able to participate in the study. We can confirm that this premise has been met, and the project is progressing according to the original research proposal.

As mentioned earlier, two community practices were chosen for study based on a previous survey: the Associação Recreativa Clube Balteiro Jovem and the EO. In order to gain knowledge, understanding and promote awareness of these initiatives, we used the following working methods (Martins et al., 2022):

Conducting ethnographic and focus group interviews aimed at (a) identifying the primary actors and participants of each practice, (b) understanding how these practices emerged, developed and were perceived by the community, and (c) understanding the impact they have had on the local and surrounding community (Coutinho, 2013; Coutinho & Chaves, 2002; Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019; Mata & Fernandes, 2019);

Video, audio and photographic records of the interviews conducted, the activity of the practices studied and the Balteiro neighbourhood. The goal is to create a bank of audiovisual material to be analysed and edited for distribution in the project’s media (Banks & Zeitlyn, 2015; Tinkler, 2013);

Analysis of documentation to learn about the historical background of the Balteiro neighbourhood and its community practices, as well as analysis of statistical data on the population of the municipality and Balteiro, provided by the social services of the Municipality of VNG.

The next step, to develop in the project’s second phase, is creating a documentary film about each case study and an online platform to make all the information collected and produced available.

4.1. The Two Community Practices Created in Balteiro: An Analysis Based on Interviews

We conducted exploratory visits to the corresponding locations between November 2021 and February 2022 to learn about these two community practices. During these visits, we interacted with the main actors and their communities through participant observation to better understand the context and its dynamics (Coutinho, 2013; Freixo, 2012; Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019). Building trust and establishing close relationships with all parties was crucial in the project’s initial phase. The project’s objectives were always explained to everyone, especially the guarantee that any sensitive information collected would not be disclosed or that the source’s anonymity would be protected if required. Additionally, all interview content would be presented to the participants and authorised through signed informed consent before publication.

After the initial participant observation phase, semi-structured interviews were conducted with Gaiurb social workers and community practice stakeholders from March 2022 to March 2023. The questions in the script were centred around the project’s goals.

The interviews did not follow a set format, and the script was continuously adapted to delve into specific topics or questions posed to each interviewee based on their answers. We aimed to provide interviewees with the flexibility to answer questions while ensuring that the interview remained relevant to the assigned topic and objectives (Coutinho, 2013; Coutinho & Chaves, 2002; Freixo, 2012; Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019; Mata & Fernandes, 2019; Sousa & Baptista, 2011).

To enhance comprehension of the design’s role in this project, we have combined two community practices in the following synthesis based on our work.

4.1.1. The Escola Oficina

The EO was created in 2015 in the Balteiro neighbourhood on the initiative of Diana Mota3. The project stemmed from the need to engage a group of 12 residents of Balteiro with work activities, aiming at their future professional reintegration. These residents were long-term unemployed with limited education.

This activity was intended to create an alternative to traditional training, such as that offered by the Instituto do Emprego e Formação Profissional or the Qualifica centres, which provided little motivation for these women. The goal was to create practical, informal and exciting training, as Diana Mota clarifies (Figure 1; interview, December 10, 2021): “this way, they are busy with something they like, they feel empowered, they are improving their education, but they don’t really realise it”.

The EO project concept was then introduced to the group of 12 residents. Only four of them initially joined the project. The others joined later, gradually. Their initial resistance was mainly due to a lack of working habits.

The EO was not created through a formal process but rather as a spontaneous initiative. At the start, there were no dedicated facilities. The activities began in the Social Work office, which served the residents of Balteiro within the development, as Diana Mota told us (interview, December 10, 2021): “at the time, I had to disable the waiting room, where the service was provided, in a small two-bedroom flat, and equip it with two sewing machines so that the women could do some work”.

The four women who initially joined the project were encouraged to dedicate part of their time to sewing whenever possible. They did not have set hours, and everyone sewed when they could. Their schedules were based on their availability.

Gaiurb and its staff did not have sewing skills, so to provide this training, they sought out partners. The first partner was SUMA, which aimed to provide rubbish and waste for potential reuse. The initial idea of EO was not only to create inclusion, education and vocational training activities but also to be a project with an environmental and circular economy awareness strand (Mota, interview, March 28, 2022).

EO found a new partner in the Escola Artística e Profissional Árvore. Despite lacking funding or support for the project, Árvore believed in EO’s strong potential and agreed to participate in a testing phase. It is worth noting that the EO began without any funding. Gaiurb and these two partner institutions provided whatever little they could, free of charge. Thus, the EO grew from the synergies between these three institutions. Diana Mota admits that the first year of implementation of the activity posed many challenges, and at times, she contemplated giving up. The main challenge was to create work habits and responsibilities in the community and a sense of commitment to the activity. To address this problem and motivate the trainees, they were provided with space, tools, materials, and training, and if they were able to create high-quality products, the possibility to sell them and keep the profits. And that was how, in the words of Diana Mota, “the machine started working” (Mota, interview, October 6, 2022).

The school began collaborating with businesses and realised that some companies required more sewists. To address this shortage, the school provided training to their trainees and helped place them in these companies. It is also worth noting that some students even received orders from outside the school. In these situations, the EO provided support which helped the trainees in their professional growth and enabled them to establish their own businesses.

The school started with the sewing activity (Figure 2), which was later extended to the cardboard packaging activity. However, in 2016, the EO left Balteiro, relocating to Santo Ovídeo, in the centre of VNG. The school has also extended its activities to include the municipality’s residents and anyone interested. The school’s activity is no longer limited to sewing and cardboard production (although they are still the main activities). Their goal is to provide the best possible training and support for those seeking to join the labour market, regardless of their background or field of interest. Should the school have in-house resources, namely in training, support is given internally. Otherwise, the school refers to its social network (Mota, interview, February 11, 2022).

Currently, the EO no longer has to reach out to citizens actively. They come to the EO seeking assistance and are mostly unemployed individuals. Additionally, most trainees are no longer from social housing and some citizens are referred to companies without training. It is worth noting that the EO is currently in contact with almost 400 companies and works with around 150 of them every week (Mota, interview, October 6, 2022).

4.1.2. The Associação Recreativa Clube Balteiro Jovem

The Associação Recreativa Clube Balteiro Jovem was formally established in April 2015 on the initiative of José Moreira, a resident of the Balteiro neighbourhood since it was built in 1967. José Moreira (interview, June 7, 2022) returned in 2010 after living abroad for some time and noticed numerous children and youngsters playing in the neighbourhood.

These children were very fond of football, and some two or three dozen kids often got together to play this sport for long hours each day. However, the matches were generally spontaneous or very disorganised, often leading to disagreements between the kids and even involving their families. José Moreira felt he had to do something for these kids who, according to him, were often hanging around the neighbourhood unattended. Then, for fun, he began to join them and help them organise street football matches, in an open field in the neighbourhood, in front of the association’s current headquarters (Moreira, interview, July 14, 2022).

The premises of the current headquarters of Balteiro Jovem are in the basement of one of the blocks of the Balteiro Development III owned by Gaiurb. At the time, in mid2011, the place was closed and not in use. The kids, and José Moreira, pressed Cláudia Santos Silva, then Balteiro’s social worker, to open the place and make it available to the community for physical activity. Cláudia Santos Silva submitted an official request to Gaiurb’s administration, which responded favourably on the condition that an adult assumed responsibility for the space.

José Moreira, a highly respected individual among young people, was chosen to take on the responsibility. Gaiurb provided the space with the condition that he dedicated himself to establishing a collectivity in the development focused on youth. This marked the start of the lengthy process of establishing the Associação Recreativa Clube Balteiro Jovem (Moreira, interview, May 4, 2022).

In 2011, the space was donated to the community, and they took responsibility for cleaning and refurbishing it. The gym was set up in a part of the space, while another small part was designated as the association’s headquarters. The community contributed towards the renovation and installation of equipment, and the parish council also offered some construction materials to support the project. Once the conditions were created, José Moreira could easily gather young people to practice sports, involving approximately 40 children. In addition to playing matches on the open field across from the association’s headquarters since 2012, they have also been invited to participate in amateur tournaments by the parish council of Vilar de Andorinho, Gaiurb, and the municipality (Moreira, athletes, coaches and caretakers of the Association Clube Balteiro Jovem, interview, January 21, 2023).

The Parish Council supported the association’s participation in tournaments by providing a van and driver for the children and assisting with their meals. José Moreira and his technical team accompanied the children and ensured their safety. Meanwhile, the teams from the Balteiro neighbourhood won numerous tournaments in the VNG area, making tournament participation a significant undertaking.

In 2015, the collectivity was formally inaugurated by Gaiurb and the local authority, with Mayor Eduardo Vítor Rodrigues in attendance. The crucial role played by José Moreira in this process is evident, as he has consistently demonstrated unwavering dedication, passion, persistence, and resilience on behalf of the community.

Balteiro Jovem’s headquarters and gym proudly showcase numerous trophies. Additionally, some of the young players from the team have been acknowledged for their skills and transferred to top clubs, including Futebol Clube do Porto. The association’s success in sports and community activities attracted children, youngsters, and parents from other areas:

we would bring numerous athletes to participate in the Youth Games, sometimes around 80 ( ... ). Our success expanded beyond our neighbourhood and became the responsibility of the Parish Council. As more children and parents started showing interest and asking if their sons could participate, I thought, “let’s expand the program to the Parish Council”. (Moreira, interview, May 4, 2022)

The community’s involvement has extended beyond the Balteiro neighbourhood and has called for improved conditions for football practice. The community’s wish came true in September 2017 with the inauguration of a new sports venue, a seven-a-side football pitch, built with the support of the VNG Municipality. Rules were established for using the space since its inception to ensure the pitch’s success. The rules also apply to the behaviour of the youngsters, both on and off the pitch. The top priority is to educate and guide young people towards healthy relationships and teamwork (Moreira, Diana Mota and athletes, coaches and tutors of the Associação Clube Balteiro Jovem, October 29, 2022).

José Moreira’s main concern today is the absence of changing rooms, particularly a toilet. The absence of this resource has caused uncomfortable situations for athletes and led to complaints from their parents. The association relies heavily on José Moreira and his high availability and dedication. The association relies on its members’ fees to cover current expenses. However, these fees are not enough to address the natural wear and tear of the space or to fund necessary improvements, like building new changing rooms. As José Moreira remarks (Figure 3; interview, June 7, 2022): “it’s an ongoing challenge!”.

4.2. The Role of Design and the Preliminary Study of Online Platform and Documentary Films

This project does not aim to present a perfect and unrealistic portrayal of these community practices. Design is not a mere cosmetic fix to hide the many challenges these practices traditionally face. The goal is to use design to connect with the target audience and evoke empathy. A responsible empathy, balancing emotion and reason: emotion, in creating narratives and techniques that inspire other citizens to take action in the community for the common good; and reason, sharing a real picture of the challenges and setbacks these practices endure, thus preventing problems and exaggerated expectations.

The replication sought for these practices should not be read linearly as simple duplication. Replication can also be interpreted as a response or rebuttal. It is crucial to ensure the debate, engaging the different individual and collective actors during the process. Communities are not all the same, so the solutions should not be either. As Diana Mota argues, the work should start with the diagnosis:

it’s all social housing, but it’s all different. Having the same type of school, like the Escola Oficina, or recreational and sports programs in every development is not feasible since the population characteristics vary. That’s why conducting a thorough diagnosis and analysing the data is crucial before implementing any intervention projects. Replicating models that don’t suit the population is pointless. (interview, February 11, 2022)

The purpose of the design is not to replicate community practices but to encourage them by sharing information responsibly. This information can help citizens make informed and responsible decisions and appropriate actions.

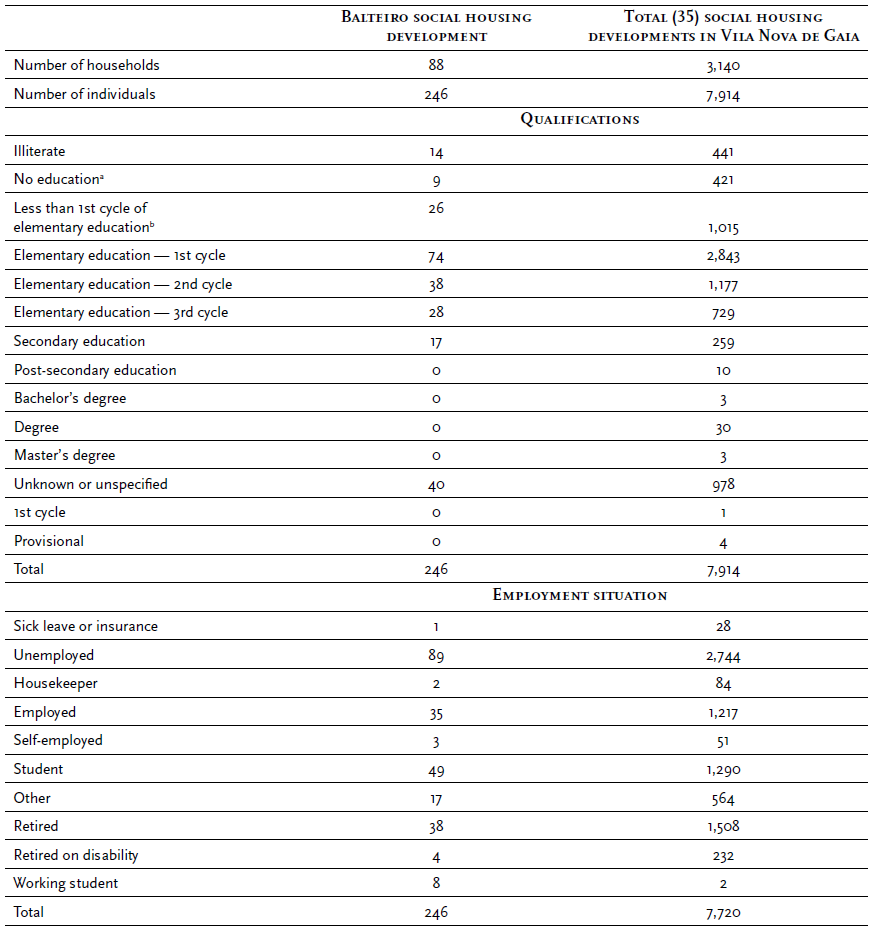

This article’s diagnostic work has directly impacted the development of documentary films and the online platform. Each documentary film’s narrative was constructed from a year-long process of intense fieldwork. This included exploratory conversations, semi-structured interviews, and recordings of relevant moments in the daily life of the association and the school. The purpose of these documentaries is to inform and inspire viewers. They should feature multiple testimonials showcasing the association and the EO’s positive impact on the neighbourhood. The visual and cinematic language used should be easily understood by a broad audience to communicate the message effectively. Before creating the online platform, an initial diagnostic study was conducted to understand better the target audience: the residents of VNG’s social housing neighbourhoods. The primary goal at this stage of the study is to promote the community practices that were started in Balteiro. The social housing neighbourhoods in this municipality have a population with low education levels and a high unemployment rate (Table 1). Gaiurb’s data report for 2022 indicates that the 35 social housing neighbourhoods in VNG had a population of 7,914 individuals. Only 4% had academic qualifications over the 9th grade, and 34.6% were unemployed. Therefore, any solution designed should cater to the unique needs of this demographic (Guimarães et al., 2023).

Table 1 Data on the qualifications and employment situation of the residents of Balteiro social housing development and the total of 35 social housing developments in Vila Nova de Gaia in November 2022

These are individuals who, despite their age, language abilities, intelligence quotient and level of education, have language, cognitive and numerical deficits (Vágvölgyi et al., 2016). Individuals with low literacy levels tend to think and communicate in a literal manner, struggling to comprehend abstract concepts and read diagonally; they analyse interfaces in a focused and limited way, examine one element at a time, and read word for word (Nielsen, 2005; Wrench, 2012). Given their difficulties, this group has specific challenges when using digital interfaces, such as navigating between pages, searching, analysing and interpreting information (Guimarães et al., 2023).

Recent literature provides recommendations for making existing interfaces accessible to this group. The recommendations include simplifying contents, interfaces, navigation and written language. They also propose adapting search systems to respond to human errors (Zaphiris et al., 2007). Authors such as Nielsen (2005) propose using simple, clear language and organising information in a list format. Presenting information in a certain way and providing specific types of information can greatly improve understanding for this particular user (Barboza & Nunes, 2017; Wrench, 2012). There are differences in the navigation mode, number of links, using tools like scrolling, and animations (Guimarães et al., 2023).

Hence, through a review and analysis of authors, such as Indrani Medhi Thies (2011), Vágvölgyi et al. (2016) and Zaphiris et al. (2007), a proposal of 12 recommendations for the design of accessible interfaces for individuals with low levels of education and literacy was developed. They are briefly presented below and grouped into design, language and information, navigation and error prevention (Table 2). It is important to consider these factors when designing platforms for this particular user group. However, it should be done without compromising the experience for other types of users.

Thus, it is advisable to use a functional and minimalist design, limiting the information on the screen. Considering the individuals’ limited visual field, and their specific analytic mode, it is necessary to present the elements one by one, with plenty of space between them, so as not to overload or distract those who access the platform. Visual cues should be used carefully, and elements should be developed so that the individual can recognise their function without having to remember them. Using clear, concise, and straightforward language is recommended, focusing only on the necessary information and organising it into relevant topics. Authors such as Barboza and Nunes (2007) suggest using clear language to tackle such users’ linguistic limitations. They propose the application of simple navigation, avoiding hierarchical navigation whenever possible since these individuals process information differently. Providing the user with the system status is also suggested.

5. Conclusion and Next Steps

This article highlights the importance of having communication designers as part of multidisciplinary teams to promote community practices in economically disadvantaged areas, such as social housing neighbourhoods.

Firstly, it underlined that, throughout history, social design and universal design are the areas of design that have been most focused on the problem of social responsibility. Among the different perspectives under analysis, we want to spotlight the recommendations of Nold et al. (2022) regarding the significance of engaging individuals, communities, and institutions in collaborative processes, as well as the insights of Margolin and Margolin (2002) emphasising the value of designers collaborating with experts from different fields. The approaches mentioned here align with the ideas presented by Chen et al. (2016) and Koskinen and Hush (2016). These authors also highlight the challenges of taking on complex projects and the dangers of having overly ambitious goals. They suggest a more localised approach involving smaller communities or informal groups with defined objectives.

Today, communication designers tend to focus primarily on market contexts when addressing social issues. In these contexts, communication design often faces the challenge of achieving commercial profitability (through product sales or financial support). Its main objective is to use captivating techniques and visual expressions to achieve these returns. A role that is naturally necessary and legitimate.

However, as this article has shown, communication design can (and should) take a holistic and close approach to these social problems through research. We gained insight into their complexity through close and collaborative work with the community, the institutions and the different stakeholders of these community practices developed in the Balteiro neighbourhood. We learned that achieving positive results was a slow and gradual process that required great persistence and resistance and that social and institutional support played a crucial role in the success of these practices. The insights from this research, which lasted around 12 months and involved close on-site observations, were essential in uncovering the complex interrelationships between different factors. Without this extensive groundwork, such conclusions would not have been possible. It confirmed the cited authors’ perspectives, converging with the ECHO project’s exploratory and molecular methodologies.

It is worth noting that this study aligns with universal design principles, as it aims to create “silent” solutions that are inclusive for everyone. In digital communication, when designing and developing an online platform for sharing community practices, it is important to ensure that all users are considered without emphasising the challenges or requirements of any specific group. The 12 design guidelines presented in this article for the design of accessible interfaces for individuals with low levels of schooling and literacy can be used as a foundation for designing an online platform that meets the needs of the target audience, the communities in social housing neighbourhoods.

The next steps of this research include the development of the online platform based on the main results obtained and presented in this article, as well as the collection, organisation and presentation of the relevant contents of each case study. These contents include details about each community practice’s unique features, presented from various stakeholders’ perspectives and shared through documentary videos.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through National Funds under the reference EXPL/ART-DAQ/0037/2021. This work was also funded by national funds through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), under the project UIDB/04057/2020.

This work is supported by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programmatic funding).

REFERENCES

Antunes, G. (2019). Política de habitação social em Portugal: De 1974 à actualidade. Forum Sociológico, 34, 7-17. https://doi.org/10.4000/sociologico.4662 [ Links ]

Armstrong, L., Bailey, J., Julier, G., & Kimbell, L. (2014). Social design futures: HEI research and the AHRC. University of Brighton. [ Links ]

Banks, M., & Zeitlyn, D. (2015). Visual methods in social research. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921702 [ Links ]

Barboza, E. M., & Nunes, E. M. de A. (2007). The Brazilian governmental websites and its readability to users with low literacy level. Inclusão Social, 2(2), 19-33. https://revista.ibict.br/inclusao/article/view/1599 [ Links ]

Chen, D.-S., Cheng, L.-L., Hummels, C., & Koskinen, I. (2016). Social design: An introduction. International Journal of Design, 10(1), 1-5. [ Links ]

Coleman, R., Clarkson, J., Dong, H., & Cassim, J. (Eds.). (2007). Design for inclusivity: A practical guide to accessible, innovative and user-centred design. Gower. [ Links ]

Coutinho, C. P. (2013). Metodologia de investigação em ciências sociais e humanas: Teoria e prática (2.ª ed.). Edições Almedina. [ Links ]

Coutinho, C. P., & Chaves, J. H. (2002). O estudo de caso na investigação em tecnologia educativa em Portugal. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 15(1), 221-243. [ Links ]

De Carlo, G. (2005). Architecture’s public. In P. B. Jones, D. Petrescu, & J. Till (Eds.), Architecture and participation (1.ª ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203022863 [ Links ]

Del Gaudio, C., Franzato, C., & Oliveira, A. (2016). Sharing design agency with local partners in participatory design. International Journal of Design, 10(1), 53-64. [ Links ]

Erskine, R. (1968). Architecture and town planning in the north. Polar Record, 14(89), 165-171. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224740005659X [ Links ]

Fernandes, L. (1998). O sítio das drogas. Editorial Notícias. [ Links ]

Fernandes, L., & Mata, S. (2015). Viver nas “periferias desqualificadas”: Do que diz a literatura às perceções de interventores comunitários. Ponto Urbe, 16, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.4000/pontourbe.2658 [ Links ]

Freixo, M. J. V. (2012). Metodologia científica: Fundamentos, métodos e técnicas. Instituto Piaget. [ Links ]

Guimarães, L., Martins, N., Pereira, L., Penedos-Santiago, E., & Brandão, D. (2023). Interface design guidelines for low literate users: A literature review. In Proceedings of 6th International Conference on Education and E-Learning (pp. 29-35). ICPS; IJIET. https://doi.org/10.1145/3578837.3578842 [ Links ]

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2019). Ethnography: Principles in practice (4.ª ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315146027 [ Links ]

Hepburn, L.-A. (2022). Transdisciplinary learning in a design collaboration. The Design Journal, 25(3), 299-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2048986 [ Links ]

Irwin, T., Kossoff, G., & Tonkinwise, C. (2015). Transition design provocation. Design Philosophy Papers, 13(1), 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2015.1085688 [ Links ]

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Random House. [ Links ]

Koskinen, I., & Hush, G. (2016). Utopian, molecular and sociological social design. International Journal of Design, 10(1), 65-71. [ Links ]

Kuure, E., & Miettinen, S. (2017). Social design for service. Building a framework for designers working in the development context. The Design Journal, 20(sup1), S3464-S3474. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352850 [ Links ]

Margolin, V., & Margolin, S. (2002). A “social model” of design: Issues of practice and research. Design Issues, 18(4), 24-30. https://doi.org/10.1162/074793602320827406 [ Links ]

Martins, N., Brandão, D., Penedos-Santiago, E., Alvelos, H., Lima, C., Barreto, S., & Roberti, A. (2022). Selfinitiated practices in the urban community of Balteiro: Design challenges in a post-pandemic setting. In A. G. Ho (Ed.), Human factors in communication of design: Proceedings of 13th International Conference on Human Factors in Communication of Design (pp. 1-7). AHFE International Open Access. http://doi.org/10.54941/ahfe1002029 [ Links ]

Mata, S., & Fernandes, L. (2019). Revisitação aos atores e territórios psicotrópicos do Porto: Olhares etnográficos no espaço de 20 anos. Civitas - Revista de Ciências Sociais, 19(1), 195-212. https://doi.org/10.15448/1984-7289.2019.1.30 [ Links ]

Mollison, B. (1988). Permaculture: Designer’s manual. Tagari Publications. [ Links ]

Nielsen, J. (2005, 13 de março). Lower-literacy users: Writing for a broad consumer audience. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/writing-for-lower-literacy-users/ [ Links ]

Nold, C., Kaszynska, P., Bailey, J., & Kimbell, L. (2022). Twelve potluck principles for social design. Discern: International Journal of Design for Social Change, Sustainable Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 31-43. https://www.designforsocialchange.org/journal/index.php/DISCERN-J/article/view/75 [ Links ]

Papanek, V. (1972). Design for the real world: Human ecology and social change. Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Blond & Briggs. [ Links ]

Sellberg, M. M., Cockburn, J., Holden, P. B., & Lam, D. P. M. (2021). Towards a caring transdisciplinary research practice: Navigating science, society and self. Ecosystems and People, 17(1), 292-305. http://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2021.1931452 [ Links ]

Shea, A. (2012). Designing for social change: Strategies for community-based graphic design. Princeton Architectural Press. [ Links ]

Shirky, C. (2010). Cognitive surplus: Creativity and generosity in a connected age. Penguin Press. [ Links ]

Simmons, C. (2011). Just design: Socially conscious design for critical causes. Adams Media. [ Links ]

Sousa, M. J. & Baptista, C. S. (2011). Como fazer investigação, dissertações, teses e relatórios. Pactor. [ Links ]

Story, M. F. (1998). Maximizing usability: The principles of universal design. Assistive Technology, 101, 4-12. http://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.1998.10131955 [ Links ]

Thies, I. M. (2014). User interface design for low-literate and novice users: Past, present and future. Foundations and Trends in Human-Computer Interaction, 8(1), 1-72. https://doi.org/10.1561/1100000047 [ Links ]

Tinkler, P. (2013). Using photographs in social and historical research. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288016 [ Links ]

Tromp, N., & Vial, S. (2022). Five components of social design: A unified framework to support research and practice. The Design Journal, 26(2), 210-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2088098 [ Links ]

Vágvölgyi, R., Coldea, A., Dresler, T., Schrader, J., & Nuerk, H.-C. (2016). A review about functional illiteracy: Definition, cognitive, linguistic, and numerical aspects. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Artigo 1617. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01617 [ Links ]

Wrench, W. M. (2012). Design and evaluation of illustrated information leaflets as an educational tool for lowliterate asthma patients [Dissertação de mestrado, Rhodes University]. SEALS. [ Links ]

Zaphiris, P., Kurniawan, S., & Ghiawadwala, M. (2007). A systematic approach to the development of research-based web design guidelines for older people. Universal Access in the Information Society, 6(1), 59-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-006-0054-8 [ Links ]

1Gaiurb - Urbanismo e Habitação, EM is responsible for urbanism, social housing and urban rehabilitation in the municipality of Vila Nova de Gaia.

2Currently, the municipality of Vila Nova de Gaia adopts the designation “social housing development” instead of “social housing neighbourhood”, emphasising the built work as opposed to a potential stigma associated with “neighbourhood”. “Neighbourhood” was also frequently used with the population of Balteiro to identify the place naturally and non-pejoratively. Considering that the focus of this project, rather than the built work, is the people who live in these housing estates, their history, experiences and community life, it seemed more appropriate to adopt the name “social housing neighbourhood”. It is also worth mentioning that there is no common denomination among the closest neighbouring municipalities of the Porto district, namely: “social housing neighbourhood” in Porto; “municipal urbanisation” in Gondomar; “housing complex” in Matosinhos; and “social housing development” in Maia.

Received: December 05, 2022; Accepted: April 10, 2023

texto en

texto en