Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.43 Braga jun. 2023 Epub 30-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.43(2023).4462

Thematic Articles

Challenges and Strategies of Digital Communication in an Educational Organization in Portugal, in the COVID-19 Pandemic Period

i Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Cultura, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal

ii Departamento de Marketing, Operações e Gestão Geral, ISCTE Business School, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

iii Faculdade de Design, Tecnologia e Comunicação, Universidade Europeia, Lisbon, Portugal

iv Departamento de Sociologia, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal

v Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

A transformação digital, acelerada pela pandemia COVID-19, transformou a forma de comunicar das organizações educativas e suscitou um conjunto de desafios que compeliram à definição de estratégias de comunicação adequadas ao contexto de crise pandémica. Face a esta realidade o presente artigo tem como objetivo compreender como uma organização educativa em Portugal adaptou a sua comunicação, em 2020, ao longo de três períodos distintos: antes da pandemia (janeiro-março), no decorrer da pandemia/confinamento (março-junho) e no regresso às aulas (setembro-dezembro). Para além disso, procura identificar e refletir sobre os desafios e estratégias de comunicação adotadas nestes períodos. Para atingir os objetivos supracitados, foi realizado um estudo de caso numa organização educativa cujos dados foram recolhidos por via de um inquérito por questionário aplicado aos encarregados de educação e de entrevistas semiestruturadas a responsáveis e dirigentes. Os resultados indicam que o contexto de crise vivenciado no período de pandemia COVID-19 impulsionou o uso da comunicação digital, nomeadamente através de ferramentas digitais (blogue, Instagram, canal YouTube), reforçou o papel da comunicação na organização educativa em estudo e alterou profundamente a forma de comunicar entre os docentes/organização educativa e os/as encarregados/as de educação. Deste modo, considera-se pertinente a definição de planos estratégicos de comunicação de crise nas organizações de ensino, a continuidade em relação à implementação e utilização de novas tecnologias e ferramentas digitais de comunicação e o estudo de sistemas híbridos que visem aumentar a agilidade e interface presencial/distância.

Palavras-chave: organizações educativas; desafios; COVID-19; comunicação digital

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the digital transformation process, significantly changing how educational organisations communicate. These changes brought numerous challenges that required the development of suitable communication strategies within the context of the pandemic crisis. In light of this situation, the objective of this article is to investigate how an educational organisation in Portugal adjusted its communication strategies during three distinct periods in 2020: before the pandemic (January-March), during the pandemic and lockdown period (March-June), and the back-to-school phase (September-December). Furthermore, this study aims to identify and analyse the challenges faced by the educational organisation during these periods and explore the communication strategies implemented. A case study was conducted within the educational organisation to accomplish these objectives. Data were collected through a questionnaire survey to parents and semi-structured interviews with heads and directors of the organisation. The findings suggest that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis context significantly increased digital communication, particularly through various digital platforms such as blogs, Instagram, and YouTube channels. This shift amplified the importance of communication within the educational organisation under study and resulted in profound changes in communication dynamics between the teachers/educational organisation and parents. Therefore, it is deemed crucial to establish strategic plans for crisis communication in educational organisations. Additionally, it is important to ensure the continued implementation and use of new technologies and digital communication tools. Moreover, hybrid systems that enhance flexibility and facilitate face-to-face and remote communication interfaces should be studied.

Keywords: educational establishments; challenges; COVID-19; digital communication

1. Introduction

Digital transformation and the use of technology are ingrained in our modern lifestyles (Orekhov, 2020) and even our education systems (Oliveira & Moura, 2015). That said, authors such as Navaridas-Nalda et al. (2020) state that true digital transformation has never been achieved in education. In fact, before the pandemic, several studies (e.g., Dwivedi et al., 2020; Simões et al., 2014; Vuorikari et al., 2020) pointed out that although schools have not been immune to the changes faced in society, they have also failed to keep up with the increased usage of digital technologies in their communication practices. However, the crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic presented educational establishments with an opportunity to harness the use of communication technologies to explore new methods of communication and improve the parent‐teacher relationship by providing easy, efficient, and effective methods of transferring information (Zieger & Tan, 2012). This unexpected transition to the virtual world, which differs significantly from classic teaching and communication models, has brought with it both new challenges and opportunities.

In the wake of these developments, this paper seeks to determine how an educational establishment in Portugal adapted its communication practices to the crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The case study employed describes the communication practices undertaken throughout 2020, before the lockdown (January-March), during the lockdown (March-June), and when schools reopened (September-December), as well as the challenges and communication strategies adopted throughout this period. In terms of the methodology used, a questionnaire was sent out to the parents/guardians of students, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with managers and directors of the educational establishment in question.

2. Digital Communication in Educational Establishments

The digital transformation of communication in educational establishments, which was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has led to a series of transformations and challenges in communication models and practices (Brammer & Clark, 2020; Moreira et al., 2020; Samartinho & Barradas, 2020). While before the COVID-19 pandemic, the literature produced viewed communication - particularly informal and face-to-face communication - as a fundamental tool in use by educational establishments (Chiavenato, 2004), recent events have brought new possibilities to light, based on the opportunities presented by the online world.

In fact, from one day to the next, the use of digital technologies became a kind of “new world” for the education system (Bento, 2020). YouTube, Skype, Google Hangout, Zoom, and other learning platforms, such as Moodle, Microsoft Teams, and Google Classroom, are examples of digital tools used in education, specifically for distance learning (Moreira et al., 2020). Other examples include those used for group communication between students, such as WhatsApp, Facebook, and Messenger (Margaritoiu, 2020). In the study by Michela et al. (2022), Twitter was pinpointed as a fundamental communication tool used by schools throughout the pandemic.

The change in communication models and practices - face-to-face communication being replaced by digitally mediated communication (Nobre et al., 2021) - led to teachers and caregivers needing to communicate in new ways (Moreira et al., 2020). Online communication between caregivers and teachers eventually became the new “norm” and the only way to maintain any form of connection during the lockdown period (Khan & Mikuska, 2021).

This change inevitably came as a challenge to educational establishments, students, and parents/guardians, who all needed to adapt their communication practices as a result (Serhan, 2020; Trindade et al., 2020). Though technologies are able to transmit image and sound, they cannot replace physical presence or provide for all the senses, specifically smell and touch. Schools have always been a place where people have come together, and for face-to-face contact, and although digital means do not negate this, they certainly reduce it (Martin & Bolliger, 2018).

Extensive literature has been produced on the communication challenges faced by universities (Andrade et al., 2020; Brammer & Clark, 2020; Charoensukmongkol & Phungsoonthorn, 2020; Karalis, 2020; Maier et al., 2020; Piotrowski & King, 2020; Radu et al., 2020). These challenges arise from a lack of adequate equipment for students, lower levels of interaction, reduced effectiveness of communication between teachers and students, and a lack of socialisation, among other factors. The following positive aspects are highlighted: closer working relationships between leadership and staff members, virtual platforms via which questions can be asked, the use of innovative teaching and communication practices, among others. Although these studies relate to universities, some of the challenges and opportunities pinpointed also apply to other educational establishments. Though this is the case, the circumstances observed in years 1-4 of primary schools proved to be more difficult due to the necessary involvement of family members in students’ education. While the pandemic encouraged family members to participate more actively in their youngsters’ education on the one hand, the circumstances faced also produced psychological challenges and problems - as well as those relating to the quality of education and inequality of opportunities - on the other (Fidan, 2021).

Other challenges highlighted include lacking the skills required to use the platforms necessary (Piotrowski & King, 2020) and a difficulty ensuring clear, effective communication between staff, students, teachers, and the educational community in general (Radu et al., 2020). In addition, pre-pandemic literature highlighted parental resistance to using technology to communicate with schools (Bordalba & Bochaca, 2019). This resistance can be put down to factors such as access to technological tools, lacking the necessary skills to use the technology, lacking willingness to use it, costs, and the time spent by teachers, among others (Bordalba & Bochaca, 2019; Goodall, 2016).

Communication and organisations can be transformational, impacting society and influencing individual perceptions and behaviours (Carareto et al., 2022). Several studies highlight the role of communication in the context of crisis (Marsen, 2020; Ndela, 2019) or uncertainty (Brammer & Clark, 2020; Ruão, 2020) and its use both in seeking answers and promoting societal cooperation (Palttala & Vos, 2011). Ruão (2020) shares the belief voiced by Brammer and Clark (2020) in the importance of communication being effective, clear, timely and complete so that it can be managed in the best way possible for the circumstances faced. Those responsible for communications should carefully select the information they wish to communicate with stakeholders and explain alternatives when communicating with the public (Marsen, 2020).

3. Methodology

This article seeks to establish the way in which an educational establishment structured its communications in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, an initial question was posed: how did the educational establishment adapt its communications during the pandemic?

A quantitative methodological approach was employed by means of the data collected via a questionnaire. The questionnaire was based on the study carried out by Ramello (2020) in Brazil on the challenges of organisational communication, and the study by Domingues (2017) on internal communication in a kindergarten in Portugal. The questionnaire was divided into three parts and contained 33 closed-ended questions and four open-ended questions. The first part (period before the pandemic - January to March 2020) sought to identify the main parent/guardian interlocutors who communicated with the educational establishment, the channels used by the various stakeholders for such communications, the frequency of communication, reasons for communication, and to evaluate the effectiveness of communication during this period. During the lockdown (March-June 2020), the previous questions were replicated, and questions were added relating to the main changes in communication practices, new technologies used, and the respective positives and negatives aspects. When schools reopened (September-December 2020), the questions from the first part of the questionnaire were replicated once again, as well as those relating to the new technologies implemented, and, finally, suggestions of changes that could be made following the COVID-19 crisis period were requested. The questionnaire was sent to the parents/guardians of primary school students in years 1-4 during May 2021 via an email containing a link to the Qualtrics platform. The responses were then analysed using the SPSS statistical software suite. A descriptive statistical analysis was performed on the closed-ended questions, while the answers given to the open-ended questions were grouped into themes.

In addition, three semi-structured interviews were conducted with the school management/directors, communications, and IT officers. Due to the pandemic, these were held both in person and online during January 2021 and May 2021. The interview script was divided into three parts: before lockdown, during lockdown, and when schools reopened. Different versions were drafted and adapted to each interviewee. The interview script was composed of: identifying the establishment, the role held in the educational establishment, age, sex, and the number of years worked in the establishment. In addition to the aforementioned components, the content of the interview aimed to address the way in which communication was carried out in the educational establishment, the perception of the effectiveness of communication by stakeholders, the communication channels used, and adaptations and changes made as a result of the pandemic. A partial transcription was made from which the interviews could be analysed. The NVivo tool was then used to structure, code, and analyse the information. A thematic analysis was then carried out - a method employed to conduct a flexible, useful analysis of qualitative data, contributing to representing the data in a way that is both rich and detailed (Gonçalves et al., 2021). The analysis was based on the following themes: communication channels, reasons and frequency of communication, challenges, and effectiveness. These themes were divided into three time periods in 2020: before the pandemic (January to March), during lockdown (March to June), and when schools reopened (September to December).

3. Presentation and Discussion of Results

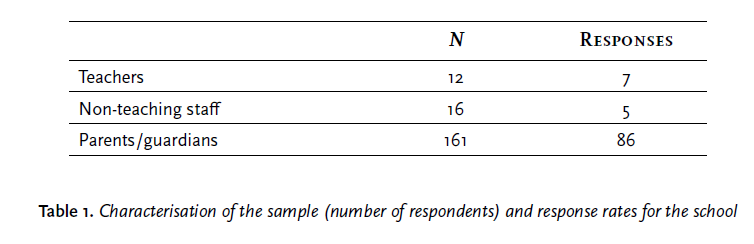

During the data collection period, the staff of years 1-4 comprised 12 teachers (six class teachers and six teaching assistants), 16 non-teachers, and 161 parents/guardians (Table 1). Of the 161 parents/guardians, 86 agreed to participate in the study, of the 16 non-teachers, five participated, and of the 12 teachers, seven answered the questionnaire.

4.1. Communication With Parents/Guardians Before, During, and After Lockdown

In the studied educational establishment, teachers were central to communications between the school and parents/guardians. Before the lockdown, 66 (51%) parents/ guardians mainly communicated with the teacher - circumstances maintained during the lockdown and when schools reopened (Table 2). These results reflect what can be considered “traditional communication” (Vuorikari et al., 2020), that is, the teacher is central to communications between the establishment and parents/guardians. As proof of this finding, a parent/guardian provided the following quote as a reply to an openended question: “everything I need to know is communicated to me by the teacher, and it is with the teacher that I liaise” (parent/guardian, 2021).

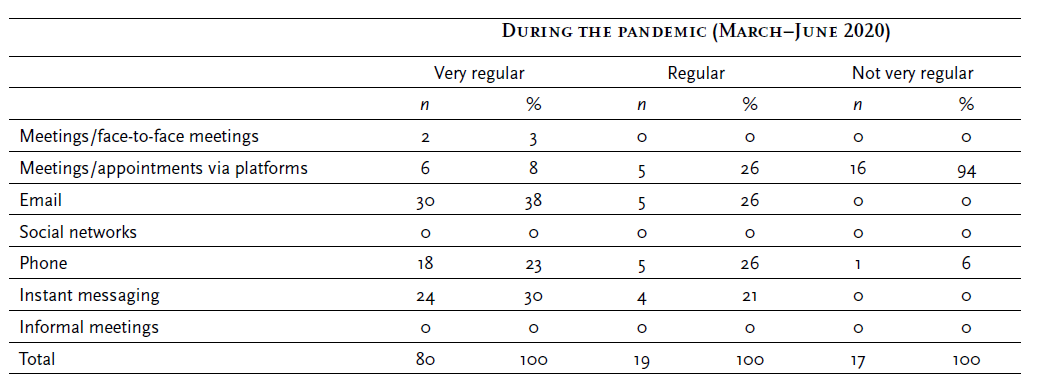

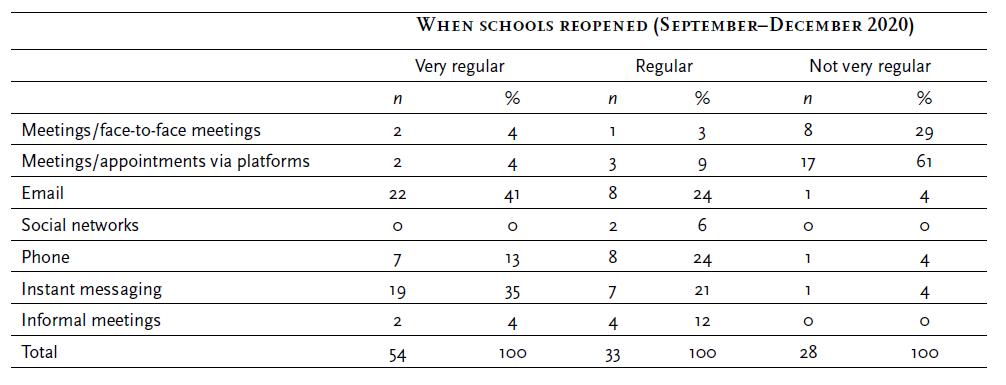

Throughout the lockdown period, communication between parents/guardians and teachers mostly took place via email and in informal meetings (Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5). This information aligns with the studies conducted by Hoy and Miskel (2008) and Lück (2006), in which they affirm that informal communication and dialogue are the most valued forms of communication in educational establishments. Although email was maintained during the lockdown and once schools reopened, the pandemic triggered the use of instant messaging. In practice, informal contact was maintained to some extent, but employing technology.

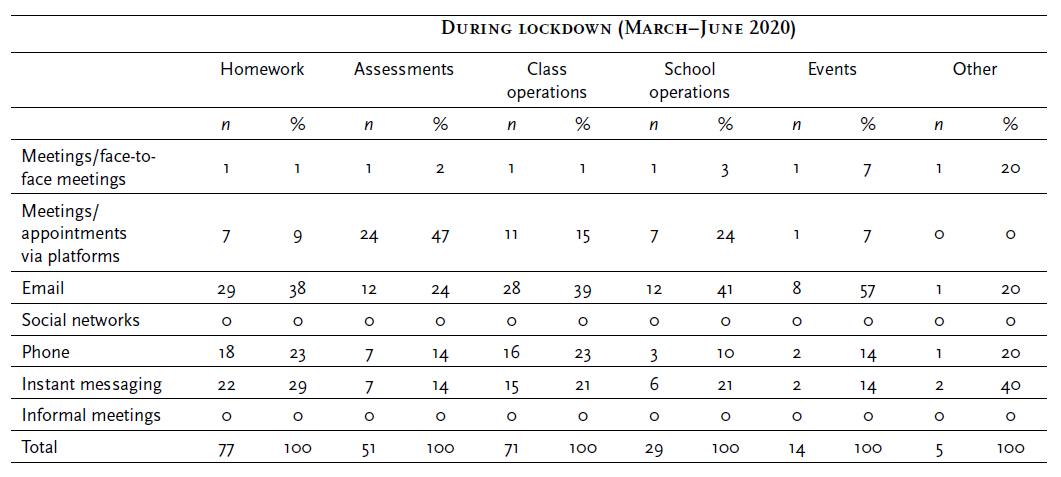

The use of communication channels varied according to the reason for the communication between parents/guardians and teachers (Table 6, Table 7, and Table 8). Before the pandemic, emails were mostly used for questions relating to school operations, events, and homework. As for informal meetings, these were called for various reasons. During the lockdown, email was mainly used for matters relating to events and school operations, and instant messages for matters relating to homework, class and school operations. Even during the lockdown, significant numbers of meetings held via platforms were noted, particularly for matters relating to assessments. When schools reopened, the trend established in the previous period was maintained, though a slight increase in face-to-face meetings was also registered for matters relating to tests. In short, email is the preferred channel for matters considered informative (e.g., school operations and events) and informal channels (e.g., informal meetings and instant messaging) for matters relating to daily life at school, specifically homework and class operations.

Table 6 Reasons for contact between parents/guardians and teachers, divided by communication channel, before lockdown

Table 7 Reasons for contact between parents/guardians and teachers, according to the communication channel, during lockdown

Table 8 Reasons for contact between parents/guardians and teachers, according to the communication channel, when schools reopened

During lockdown, communication practices in educational establishments underwent several transformations due to the transition from face-to-face to distance learning. During this time, teachers and caregivers were forced to adapt and use digital technologies in their daily activities. While the use of technologies in the educational establishment was almost non-existent before the pandemic, it became an essential tool for both work and communication during lockdown. During this time, email, instant messaging, and meetings/classes conducted via digital platforms were the most frequently used forms of communication. As Vuorikari et al. (2020) mention, the use of digital technologies in this unpredictable, unprecedented situation - the transition from face-to-face to remote teaching - fostered new ways of learning, working, and communicating. In fact, literature on the subject mentions that the COVID-19 pandemic period accelerated the need for the preparation and integration of digital technologies into education (Samartinho & Barradas, 2020).

4.2. Dilemmas and Challenges of Digital Communication

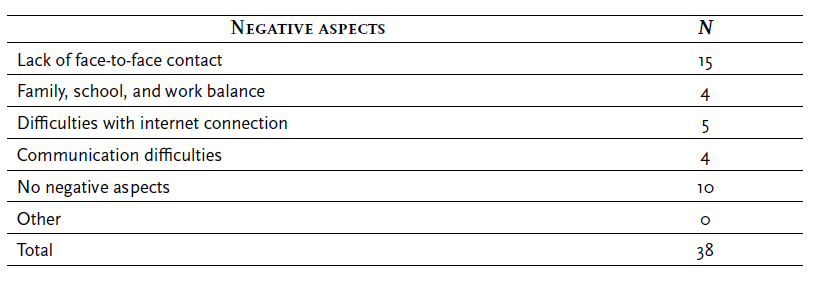

Educational establishments and communication inevitably face challenges in any period of crisis and sudden change, and our case study was no exception. For parents/ guardians, the most significant communication challenges faced (Table 9) related to the difficulties arising from the lack of face-to-face contact. Issues relating to difficulties connecting to the internet, striking a balance between family, school, and work life, and communication are mentioned: “at first, the information was provided via several channels (Microsoft Teams, email, and WhatsApp) and not always homogeneously, which initially caused some confusion”.

Table 9 Negative aspects pointed out by parents/guardians in the use of new communication channels during lockdown

When asked about the main positive aspects of the communication experienced (Table 10), of the 35 open-ended responses obtained, 18 parents/guardians noted the clarity of communications as a positive aspect, and a further 18 the consistency of communications. Where the consistency of communications is concerned, the main aspects noted were: “how quickly the school adapted to the circumstances”, the “constant communication between the school and families”, the school’s ability to “maintain communication with parents from when students were sent home, notifying parents of the measures taken so that classes could continue, even if remotely”. The “daily availability of communications” and “continuous involvement of families throughout the online classes” played a “fundamental guiding role”. A parent/guardian said the educational establishment became “more present and available, communicating closely with families, despite the distance”. These ideas converge with the study conducted by Brammer and Clark (2020), according to which this period brought about positive changes, such as bringing people closer together, specifically teachers and parents/guardians, in this case. Where clarity is concerned, it was pointed out that communication was based on “honesty” and “clarity”. Thus, “regular communication, the humility to admit that they did not know the answer to a question when they actually did not know, and stating what drives the school with no shame or fear” were considered important aspects that contributed to “inspiring confidence”.

4.3. Digital Communication Strategies

From the point of view of the educational establishment, the difficulties faced related to anticipating unknown scenarios and managing all requests. Lockdown “was a challenging, enriching time of great learning” (head teacher of the educational establishment, 2021) that required several modifications, adaptations, reflections, and actions to be taken in the studied educational establishment. The communication practices adopted throughout the lockdown period were seen as “an opportunity to broaden our communication horizons” (communications officer, 2021).

As for educational establishments, the relevant literature is very specific regarding the importance of selecting which information to communicate, establishing timely communications, and being careful of the way different audiences are communicated with in a crisis context (Andrade et al., 2020; Brammer & Clark, 2020; Marsen, 2020; Radu et al., 2020). For this reason, throughout lockdown, “everything was managed very thoughtfully and attentively, with a timely response given to each mother and father ( ... ) potentially controversial or delicate matters, when they should be kept quiet and when they needed to be shared” (communications officer, 2021). This data is consistent with several studies (e.g., Coombs, 2015; Knight, 2020; Wong et al., 2021) that demonstrate the importance of reducing and preventing alarmism in the transmission of messages in a crisis context.

It is also important to convey messages in a way that is true, transparent, and empathetic. Additionally, a clear message should be shared that is responded to, and advice provided when needed (Coombs, 2015; Knight, 2020; Wong et al., 2021). Throughout this period, the importance of clear, transparent communication between teachers, students, and parents/guardians was reinforced so that the necessary information was passed on to students in the best possible way:

if I talk to the kids in the morning knowing that they’re going to spend the day with their teachers, it’s important that the teachers understand what I’m saying, as well as for the teachers to know that I cherish, respect, expand upon, stand behind, and support what they’re going to say throughout the day. Reality, telling kids real things. Adjusting the clearest, most transparent item and giving children useful information. (Board member, 2021)

One of the strategies adopted throughout this period was a commitment to regular, effective communication to reduce uncertainties and mistrust. The communications officer uses the period in which schools reopened as an example to explain that:

when schools reopened parents were no longer allowed into the school - a rule we have maintained. As a result, what we communicate has become even more important. When faced with uncertain times, we must ensure that everything is kept as it was before, that classes are being held, students are safe, our mission is being met, and the school-parent relationship continues to be nurtured. It is no longer possible to walk into the school, stop for a chat, make your way to a classroom, or take part in break time; all this generates uncertainty and mistrust that must be managed through regular, effective communication.

As described by a board member of the educational establishment, “there were many zooms, many meetings, even with parents. In the first phase, emails were sent out almost daily to parents, many phone calls”. They also add that “in the beginning, we called a Zoom meeting ( ... ). Morning follow-up meetings were held at seven or in the afternoon, sometimes even including the deputy head teachers of each school, key stage leaders, and the finance director”. However, they believe that during lockdown, the communication strategy consisted of:

trying not to voice too many opinions. The issue was working out how we could continue to educate our students given the circumstances faced and our educational system. We often try to keep our communication to what we consider to be essential, not wasting communication time with irrelevant information. (Board member, 2021)

A document was also created that sought to answer all the questions asked by parents/guardians.

All the questions, FAQ [Frequently Asked Questions], were mapped in a very interactive document that worked as a guide in which parents could seek out answers. A very important objective behind creating this document was to combine and channel all the information into a single physical medium to avoid the dispersal of information. It was very important that we create this document and release it directly to parents. (Communications officer, 2021)

In addition, digital communication and particularly “social networks were of paramount importance” (communications officer, 2021) as communication methods.

However, other forms also came into use during the lockdown period. Instagram, social networks, and communication via images is also very good communication. We didn’t really communicate by these means previously, but it was interesting to communicate via videos and photographs, showing what was being done. This should be improved so as to clearly convey what we intend to communicate. (Board member, 2021)

The communications officer points out that the educational establishment:

started telling daily stories on Instagram. Started a blog to narrate the creative and cultural life of students and teachers. Became more present on social networks by posting class photos, initiatives, challenges, games, and proposals; it began to hold parents’ evenings on Zoom; it began to adopt new teaching practices adapted to Zoom; its teachers became even more creative and open; more “tech-savvy” teachers.

Before the pandemic, the studied establishment was not concerned about having “more online things, a more sophisticated website: they were not our priorities. The new circumstances meant they became precious” (board member, 2021). The communications officer further stated:

deep down, what happened pre-COVID was that the “normal “ channels of communication all related to communication per se. Post-COVID, everything - classes, teacher initiatives, communications to parents, communications to students, information about fees, challenges, games, readings, calendar information - took place via email, on YouTube, Zoom, Instagram, on the blog... we faced a considerable challenge in terms of our people - our workforce - but also a great adventure. All of us - not just me - came out the other side more capable and focused on what is essential. We have gained new tools (blog, improved planning of the task of communication, etc.), and new skills.

5. Final Remarks

This study sought to establish the ways in which an educational establishment in Portugal adapted its communications within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In view of the crisis experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, the results indicate that digital communication reinforced the role of communication in the studied educational establishment and profoundly changed the methods of communication used between teachers/the educational establishment and parents/guardians.

The unexpected virtual transition enhanced the use of digital tools, specifically the school’s blog, Instagram, and YouTube channel, revolutionising teaching, learning, working, and communications.

Communication is an essential tool in any transition or crisis. As such, the following factors were considered to be relevant: (a) establishing strategic crisis communication plans in educational organisations based on guidelines developed for prevention, preparation, and crisis management; (b) establishing continuity in the implementation of new technologies and digital tools alongside parents/guardians; and (c) the study of hybrid systems that aim to increase flexibility and face-to-face/distance learning.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programmatic funding). We also thank all the study participants who made it possible to obtain the data.

REFERENCES

Andrade, J. G., Ruão, T., & Oliveira, M. (2020). Os bastidores da comunicação de risco: A UMinho em tempos de pandemia. UMinho Editora. [ Links ]

Bento, M. (2020, 24 de março). Ser professor e “COVIDado” a reinventar-se. Público. https://www.publico.pt/2020/03/24/impar/opiniao/professorcovidadoreinventarse-1909064 [ Links ]

Bordalba, M., & Bochaca, J. (2019). Digital media for family-school communication? Parents’ and teachers’ beliefs. Computers & Education, 132, 44-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.006 [ Links ]

Brammer, S., & Clark, T. (2020). COVID-19 and management education: Reflections on challenges, opportunities, and potential futures. British Journal of Management, 31, 453-456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12425 [ Links ]

Carareto, M., Andrelo, R., & Ruão, T. (2022). How can organizational communication impact society? Reflections from the communication practice in Portuguese communication agencies. Revista Internacional de Relações Públicas, XII(23), 163-184. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v12i23.754 [ Links ]

Charoensukmongkol, P., & Phungsoonthorn, T. (2020). The interaction effect of crisis communication and social support on the emotional exhaustion of university employees during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Business Communication, 59(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488420953188 [ Links ]

Chiavenato, I. (2004). Introduçao à teoria geral da administração. Elsevier Editora. [ Links ]

Coombs, W. T. (2015). Ongoing crises communication. SAGE. [ Links ]

Domingues, M. (2017). Desafios da comunicação interna numa creche. Proposta para a definição de um plano de comunicação interna numa creche no concelho de Lisboa [Dissertação de mestrado, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa]. Repositório do Iscte - Instituto Universitário de Lisboa. http://hdl.handle.net/10071/15039 [ Links ]

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, D., Coombs, C., Constantiou, I., Duand, Y., Edwards, J. S., Gupta, B., Lal, B., Misra, S., Prashant, P., Raman, R., Rana, N. P., Sharma, S. K., & Upadhyay, N. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102211 [ Links ]

Fidan, M. (2021). COVID-19 and primary school 1st Grade in Turkey: Starting primary school in the pandemic based on teachers’ views. Journal of Primary Education, 3(1), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.52105/temelegitim.3.1.2 [ Links ]

Gonçalves, S., P. Gonçalves, J., & Marques, C. G. (2021). Manual de investigação qualitativa. Pactor. [ Links ]

Goodall, J. S. (2016). Technology and school-home communication. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 11(2), 118-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/22040552.2016.1227252 [ Links ]

Hoy, W., & Miskel, C. (2008). Educational administration: Theory, research and practice. McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Karalis, T. (2020). Planning and evaluation during educational disruption: Lessons learned from COVID-19 pandemic for treatment of emergencies in education. European Journal of Education Studies, 7(4), 125-142. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v0i0.304 [ Links ]

Khan, T., & Mikuska, É. (2021). The first three weeks of lockdown in England: The challenges of detecting safeguarding issues amid nursery and primary school closures due to COVID-19. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), Artigo 100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2020.100099 [ Links ]

Knight, M. (2020). Pandemic communication: A new challenge for higher education. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 83(2), 131-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329490620925418 [ Links ]

Lück, H. (2006). A gestão participativa na escola. Vozes. [ Links ]

Maier, V., Alexa, L., & Craciunescu, R. (2020). Online education during the COVID19 pandemic: Perceptions and expectations of Romanian Students. Proceedings of European Conference on e-Learning, 317-324. https://doi.org/10.34190/EEL.20.147 [ Links ]

Margaritoiu, A. (2020). Student perceptions of online educational communication in the pandemic. Jus et civitas, VII(1), 93-100. [ Links ]

Marsen, S. (2020). Navigating crisis: The role of communication in organizational crisis. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(2) 163-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488419882981 [ Links ]

Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1), 205-222. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092 [ Links ]

Michela, E., Kimmons, R., Sultana, O., Burchfield, M. A., & Thomas, T. (2022). “We are trying to communicate the best we can”: Understanding districts’ communication on twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic. AERA Open, 8, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584221078542 [ Links ]

Moreira, J. A., Henriques, S., & Barros, D. (2020). Transitando de um ensino remoto emergencial para uma educação digital em rede, em tempos de pandemia. Dialogia, (34), 351-364. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.2/9756 [ Links ]

Navaridas-Nalda, F., Emeterio, M.-S., Fernández-Ortiz, R., & Arias-Oliva, M. (2020). The strategic influence of school principal leadership in the digital transformation of schools. Computers in Human Behavior, 112, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106481 [ Links ]

Ndela, M. N. (2019). Crisis communication a stakeholder approach. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Nobre, A., Mouraz, A., Goulão, M. de F., Henriques, S., Barros, D., & Moreira, J. A. (2021). Processos de comunicação digital no sistema educativo português em tempos de pandemia. Revista Práxis Educacional, 17(45), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v17i45.8331 [ Links ]

Oliveira, C., & Moura, S. P. (2015). TIC’S na educação: A utilização das tecnologias da informação e comunicação na aprendizagem do aluno. Pedagogia em Ação, 7(1), 75-95. http://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/pedagogiacao/article/view/11019 [ Links ]

Orekhov, M. (2020). The essence of the digitalization process as a new global information stage. Information and Communications, (1), 68-85. [ Links ]

Palttala, P., & Vos, M. (2011). Testing a methodology to improve organizational learning about crisis communication by public organizations. Journal of Communication Management, 15(4), 314-331. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632541111183370 [ Links ]

Piotrowski, C., & King, C. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and implications for higher education. Education, 141(2), 61-66. [ Links ]

Radu, M.-C., Schnakovszky, C., Herghelegiu, E., Ciubotariu, V.-A., & Cristea, I. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of educational process: A student survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), Artigo 7770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217770 [ Links ]

Ramello, C. A. (2020). Desafios da COVID-19 para a comunicação organizacional. Aberje. [ Links ]

Ruão, T. (2020). A emoção na comunicação de crise - aprendizagens de uma pandemia. In M. Oliveira, H. Machado, J. Sarmento, & M. C. Ribeiro (Eds.), Sociedade e crise(s) (pp. 93-101). UMinho Editora. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/68130 [ Links ]

Samartinho, J., & Barradas, C. (2020). Editorial: A transformação digital e tecnologias da informação em tempo de pandemia. Revista da UI_IPSantarém, 8(4), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.25746/ruiips.v8.i4.21965 [ Links ]

Serhan, D. (2020). Transitioning from face-to-face to remote learning: Students’ attitudes and perceptions of using Zoom during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 4(4), 335-342. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.148 [ Links ]

Simões, J. A., Ponte, C., & Ferreira, E. (2014). Crianças e meios digitais móveis em Portugal: Resultados nacionais do projeto Net Children Go Mobile. Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. [ Links ]

Trindade, S. D., Correia, J. D., & Henriques, S. (2020). O ensino remoto emergencial na educação básica brasileira e portuguesa: A perspectiva dos docentes. Tempos e Espaços em Educação, 13(32), Artigo e-14426. https://doi.org/10.20952/revtee.v13i32.14426 [ Links ]

Vuorikari, R., Velicu, A., Chaudron, S., Cachia, R., & Di Gioia, R. (2020). How families handled emergency remote schooling during the COVID-19 lockdown in spring 2020. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/31977 [ Links ]

Wong, I. A., Ou, J., & Wilson, A. (2021). Evolution of hoteliers’ organizational crisis communication in the time of mega disruption. Tourism Management, 84(6), Artigo 104257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104257 [ Links ]

Zieger, L. B., & Tan, J. (2012). Improving parent involvement in secondary schools through communication technology. The Journal of Literacy and Technology, 13(1), 30-54. [ Links ]

Received: December 11, 2022; Accepted: March 20, 2023

texto en

texto en