Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.43 Braga jun. 2023 Epub 01-Mayo-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.43(2023).4102

Varia

Digital Content in Brazilian Sign Language (Libras): A Study of Brazilian Channels of Deaf People on YouTube

iPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Letras e Linguística, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil

iiDepartamento de Libras e Tradução, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil

iiiEstudios de Ciencias de la Información y de la Comunicación, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

O tema deste estudo é a produção e a autoria de pessoas surdas na internet, especificamente, na plataforma de compartilhamento de vídeos e rede social YouTube, no Brasil. Trata-se de um tema de vanguarda e desvela a relação dos surdos com uma mídia digital que privilegia o vídeo, elemento este que está intimamente relacionado ao artefato cultural do povo surdo (Strobel, 2016), e valoriza a língua de sinais, que é a experiência visual. O objetivo é investigar os temas produzidos, exclusivamente em língua brasileira de sinais (Libras), por pessoas surdas nos canais do YouTube. A metodologia da pesquisa possui uma abordagem qualitativa do tipo descritiva (Gil, 2002) e utiliza, para a coleta de dados, o método dos principais itens para relatar revisões sistemáticas e meta-análises (Prisma; Page et al., 2021) com o tipo de amostragem de bola de neve (Vinuto, 2014). Foram identificados 913 vídeos postados em 11 canais de autores surdos brasileiros no YouTube, ao longo de nove anos, entre 2006, ano da criação do canal mais antigo analisado, e 2021. Os autores que contribuíram com a análise foram principalmente Festa (2012), Burgess e Green (2009/2009), Coruja (2017) e Medeiros e Rocha (2018). A partir da análise dos vídeos, foi possível identificar uma maior quantidade de vídeos com temas financeiros e observar que os vídeos com mais visualizações são sobre a língua de sinais, a identidade e a cultura surda.

Palavras-chave: língua brasileira de sinais; YouTube; surdo; Brasil; mídia digital

The subject of this article is the production and authorship of deaf people in Brazil on the internet, specifically on the video-sharing platform and social media YouTube. This cutting-edge theme unveils the relationship of deaf people with digital media that privileges video, an element closely related to the cultural artefact of deaf people (Strobel, 2016) and values sign language, which is the visual experience. It aims to explore the themes produced, exclusively in Brazilian sign language (Libras), by deaf people on YouTube channels. The research methodology has a qualitative approach of the descriptive type (Gil, 2002) and uses, for data collection, the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses method (Prisma; Page et al., 2021) with the snowball sampling type (Vinuto, 2014). We identified 913 videos uploaded on 11 Brazilian deaf authors’ YouTube channels over nine years between 2006, the year the oldest channel analysed was created, and 2021. The contributing authors to the analysis were mainly Festa (2012), Burgess and Green (2009/2009), Coruja (2017) and Medeiros and Rocha (2018). The analysis of the videos allowed identifying more videos with financial themes and observing that the videos with more views are about sign language, identity and deaf culture.

Keywords: Brazilian sign language; YouTube; deaf; Brazil; digital media

1. Introduction

Throughout history, several assumptions have been created about the deaf person. Due to these assumptions, the deaf faced many hardships to be respected as human beings because it was believed that reasoning ability was linked to speech. So, they were considered incapable of thinking and learning for a long time (Schlünzen et al., 2013). According to Moura (1996, as cited in Valiante, 2009), in Greece, “Aristotle (384 BC-322 BC) stated that the deaf did not possess language. Because they were considered incapable, they were marginalised, grouped with the sick and mentally disabled or even sentenced to death” (p. 7).

However, this scenario started to change when, from the 15th century, important research on deafness was conducted because noble families with deaf children were worried about not losing their wealth. Thus, it was necessary to understand deaf people better and integrate them into society. Furthermore, the Church was interested in promoting communication between the deaf and God so that the person would not “lose their soul” (Schlünzen et al., 2013).

Since then, several techniques for deaf instruction have been developed and improved over the years. Lacerda (1996) reports that it was common to keep the method used in the education of the deaf a secret since each teacher worked alone and did not share their experiences. Therefore, there are no records of many of the techniques developed, and they were lost over time. The Spanish Benedictine monk Pedro Ponce de Leon (1520-1584) is considered the first teacher of the deaf.

Although many teaching techniques for the deaf were developed then, Lacerda (1996) notes that only the deaf from wealthy families were privileged with this education. Despite each teacher’s different methodologies, we can divide the techniques into two large groups: oralist and gesturalist. The oralists “demanded that the deaf rehabilitate themselves, to overcome their deafness, to speak and, in some way, to behave as if they were not deaf” (Lacerda, 1996, p. 6). The gesturalists “could see that the deaf developed a language that, although different from oral, was effective for communication and opened the doors to understanding culture” (p. 6).

The French abbot Charles-Michel de L’Epée (1712-1789), also known as the “father of the deaf” and “inventor of sign languages”, is the most important reference to the sign language approach. From observations of deaf people groups, he realised that they could develop communication supported by the visual-gestural channel. So, he created an educational method combining the sign language of the deaf community and the signs he developed. He named the system “methodical signs” (Lacerda, 1996, p. 9).

With Law No. 10.436 (Lei nº 10.436, 2002), the deaf community in Brazil conquered in 2002 the recognition of the Brazilian sign language (Libras) as a legal means of communication and expression of the deaf. Such law, regulated by Decree No. 5.626 (Decreto nº 5.626, 2005), which addresses the access of deaf people to education in their natural language, marked positively not only access to sign language in the classroom context but also its dissemination among the deaf people.

In the context of the deaf community’s achievements, this article focuses on the production and authorship of deaf people through sign language on the internet, specifically on the social media YouTube. Technology has completely revolutionised communication as we know it. What, two decades ago, would need to be broadcast on television channels to reach large audiences can now be easily disseminated through social media. According to Festa (2012), “social media is defined as a virtual space where it is possible to interact with a large number of people at the same time and in the same place” (p. 27). Hence, social media have opened a range of possibilities for the propagation of all kinds of content, allowing free video, photo and text sharing.

One such social media is YouTube, a video-sharing platform created in June 2005 by Chad Hurley, Steve Chen and Jawed Karim (Festa, 2012). YouTube has content for all ages and audiences. It can be accessed for free, provided that, in some cases, videos are interspersed with advertising. It is also possible to subscribe to YouTube Premium for a monthly fee to watch videos without advertisements and to download videos, among other benefits.

Thanks to these resources, people with Libras as their first language can communicate and express themselves through videos, such as those broadcast on YouTube. Thus, it is clear that this virtual environment has been characterised as a conveyor of sign language and communication of deaf culture’s content. Many deaf people have used this tool to produce content about the deaf culture, aimed both at the deaf community and at people unfamiliar with sign language.

It is worth noting that for many years being deaf was deemed as something negative by society. According to Strobel (2016), “people are not aware and do not know what the deaf world is like and make erroneous assumptions about deaf people” (p. 23).

Hence, YouTube has then become not only a forum for the dissemination of deaf culture and demystification of myths about the deaf community but also a platform providing the deaf with the freedom to talk about politics, fashion, film and finance, among other topics, without the mediation of sign language interpreters. In other words, the deaf found a channel to communicate autonomously using their own language.

We can already find numerous research addressing the relationship of the deaf person with YouTube (Festa, 2012; Pinheiro & Lunardi-Lazzarin, 2013; Silveira & Amaral, 2012). Nonetheless, new studies are needed since YouTube is constantly changing, as pointed out by Burgess and Green (2009/2009):

YouTube, ( ... ), is a particularly unstable object of study, marked by dynamic changes (both in terms of videos and organisation), diversity of content (which moves at a different pace from television but similarly oozes through the service and sometimes disappears) and an equal daily frequency, or “sameness”. (p. 23)

Therefore, this article aims to explore the themes produced exclusively in Libras by deaf people on YouTube channels in Brazil, classifying the themes of the videos. We seek to answer the following questions: which YouTube channels are produced by Brazilian deaf people? What subjects feature in the videos? Which contents are most viewed?

To do so, we initially present a brief explanation of what YouTube is to contextualise the theme, followed by a description of the methodology used and the presentation and discussion of the data found.

2. About YouTube: Broadcast Yourself

In 2005, amid the context of technological development, a platform was created to facilitate video sharing on the internet, YouTube, which, despite competing services, became popular for having a simple and intuitive interface that did not require great technical knowledge to be used (Burgess & Green, 2009/2009). In other words, apart from those assumptions of sharing and connecting, which reflect the expansion of the possibility of communicating and accessing information, there is now the expansion of language, adding movement, images, sounds, videos, among others.

Morán (1995) stated that video is a “sensorial, visual, musical and written spoken language” (p. 28) media. According to the author,

video seduces, informs, entertains, and projects us into other realities (in the imaginary) and other times and spaces. The video combines sensory-kinaesthetic and audiovisual communication, intuition and logic, and emotion and reason. It combines but begins with the sensory, the emotional and the intuitive to later reach the rational. (Morán, 1995, p. 28)

In this sense, video is related to deaf culture and the visual nature of sign language, giving YouTube a certain significance for the deaf community. Burgess and Green (2009/2009) highlight features important for its growth, such as the possibility of connecting with friends, commenting on videos, generating URLs and HTML codes to embed the videos in other websites, and not setting a limit on the number of videos uploaded. This popularisation caught Google’s attention, and in October 2006, it bought the streaming service for US$1,650,000,000. After this transaction, YouTube underwent a re-signification and consolidated itself with the slogan “broadcast yourself”, standing out as a space for the personal expression of its users (Coruja, 2017).

In 2007, as highlighted by Medeiros and Rocha (2018), the YouTube partnership program was launched. It pays the creators of original content according to the views of the channel’s videos, encouraging new users to join the platform.

What used to be restricted to content provided by a website or portal, with almost no room for public feedback, has increased the space for people to share their visions and ideas. That made it possible for internet users to become not only consumers of content but also producers. (Medeiros & Rocha, 2018, p. 8)

Bernardazzi and Costa (2017) use the term “youtuber” to identify those who “have channels on the YouTube website, who post audiovisual products and, from this, may eventually have a financial return and turn this activity into a professional career” (p. 152). The authors point out that

unlike the traditional audiovisual market, including video production companies, television stations and film production companies, whose creation of the audiovisual product is shared among several professionals, each one performing their function - general direction, photography, production, editing, set design, lighting, among others, on YouTube we have the prominence of a content producer who, sometimes, is the only part in the process of creating the videos for the internet. Thus, a single “professional” takes part in the production process of audiovisual content (Bernardazzi & Costa, 2017, p. 152)

That brings the content producer closer to his audience, as he thoroughly knows every part of the video creation process. Moreover, on YouTube, it is possible to interact directly with viewers through comments and likes on the videos, establishing a relationship between producer and consumer who dialogue and flow in such a way that can even alternate, enabling this interaction, especially with viewers who identify with the uploaded content (Bernardazzi & Costa, 2017; Burgess & Green, 2009/2009; Coruja, 2017; Medeiros & Rocha, 2018).

Carvalho-Lima et al. (2021) studied the narratives about deafness in videos uploaded in 2018 and 2019, in Portuguese, on YouTube. The authors included search terms such as “deaf” and “deaf-mute” and identified a predominance of narratives that link deafness to a disability or with a disease bias.

Meanwhile, Galindo-Neto et al. (2021) analysed 402 videos produced in Libras and uploaded on YouTube in 2020 about the coronavirus related to the health area aimed at the Brazilian audience. In this case, the authors also used search keywords (“coronavirus” and “Libras”). They identified that: (a) the longer the video, the greater the number of views, which, for the authors, may have happened because the longer videos were mostly bilingual (Libras and Portuguese) and reached a larger audience; (b) 64.7% of the videos were uploaded by individuals and another 35.5% were videos uploaded by institutional channels; and (c) the themes of the videos were mostly about prevention (20.6%), general information (18.9%) and news about coronavirus (16.9%).

In this sense, YouTube has received a certain prominence in numerous research, such as studies on educational potential (Asensio, 2018; Silva, 2011) and studies on state-of-the-art, focused on what has been broadcast and its impact (Galindo-Neto et al., 2021; Sixto-García et al., 2021). Sixto-García et al. (2021), meanwhile, go as far as to develop the proposal of a method of analysis of YouTube channels of mainstream media companies, the so-called “digital native journals”. To these authors, many of the institutional channels on YouTube commune with multiplatform and cross-media and the study method developed is based on how they are narrated, whether they use repositories or if there are also transmedia narratives engaging with these channels.

In our study, the focus of analysis is to map “the voice” that the deaf are echoing in their visual language, sign language, within this far-reaching social media. It focuses more specifically on the protagonism of deaf people (individuals exclusively) and what they have been posting, the recurring themes and the volume of access to these themes. The study methodology chosen is the same developed in literature review studies (similar to the studies by Carvalho-Lima et al., 2021; Galindo-Neto et al., 2021).

3. Methodology

The methodology of the study described in this article has a qualitative approach. Although it collects quantitative data, the focus of the analysis is qualitative since it aims at identifying themes and the relationship of these numerical data with the social and cultural context of the deaf.

It is a descriptive type of research. According to Gil (2002), this type of research mainly focuses on describing characteristics and factors that make up certain phenomena. The data collection strategy follows the assumptions of a systematic review, following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses method (Prisma). This method is intended to help the researcher make sure that their review clearly explains the rationale for the research, how it was conducted and what the outcomes were through a 27-item checklist so that the process of data identification, selection, eligibility and inclusion is accomplished effectively (Page et al., 2021).

Snowball sampling was used to identify and analyse the channels produced by deaf people, which is “a form of non-probabilistic sampling that uses reference chains” (Vinuto, 2014, p. 201). The channel search was done on the YouTube video-sharing platform throughout August 2021, and their analysis was conducted throughout September and October 2021.

On the YouTube website platform, each channel has a tab with the name “channels”, where the channel owner arbitrarily chooses what will be displayed, which can be: subscriptions to other channels; subscriptions to other channels and featured channels; featured channels; or no channels at all. In this research, we considered searching only featured channels. The channel owner selects the channels they wish to display in this tab. This methodological choice was used because it was possible to verify that all the channels analysed opted to expose in the featured channels tab other channels with the theme aligned with that of the channel itself, enabling the snowball method application.

Thus, the first step was to locate a channel with content in Libras produced by a deaf person. So, the search for the descriptor Libras deafness was done in the search field on the YouTube website. The first video on the searched list had the title Surdez É um Problema? | Libras • Léo Viturinno (Is Deafness a Problem? | Libras • Léo Viturinno), and after clicking on the channel, the “about” tab was accessed, with information about the channel owner. Thus, it was possible to verify that he is deaf and Brazilian and produces videos in Libras. Léo Viturinno’s “featured channels” were identified by the title “Youtubers Surdos” (Deaf Youtubers) and showed five other channels. From then on, it was possible to locate other channels applying snowball sampling (Vinuto, 2014).

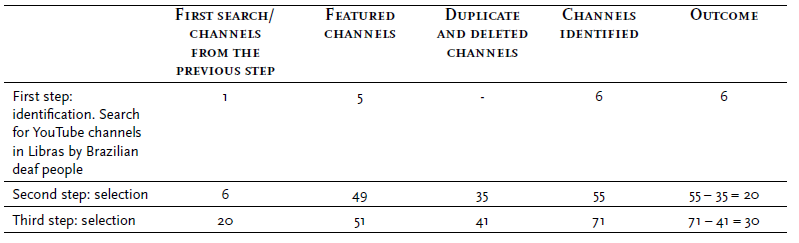

In the second step, by analysing these five other channels’ “featured channels” tab, we found another 55 featured channels options, which, after excluding the duplicates, were narrowed down to 20 channels. The third stage involved working with the 20 new channels, generating another 51 channel records, totalling 71 options. After excluding the duplicated channels again, a total of 30 channels remained. Thus, after the third step, we reached sample exhaustion (Vinuto, 2014), consisting of the repetition of indications already traced without presenting significant numbers of new records since only nine were new options out of the 51 new records.

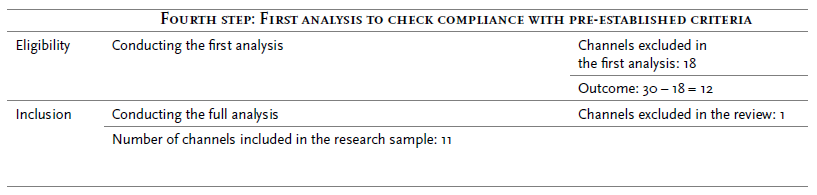

The fourth step was the qualitative analysis for the inclusion and exclusion of channels that met the research criteria. The data inclusion criteria in the research sample were: channels created by Brazilian deaf people, videos in Libras with more than 1,000 subscriptions and recently updated (with at least one video uploaded in the year 2021). The exclusion criteria were: channels created by listeners, videos in another language other than Libras, channels without recent updates and channels with less than 1,000 subscriptions.

Thus, after applying the fourth step, 18 channels were excluded from the 30 channels identified: 12 channels with no recent updates, three in another language, two with less than 1,000 subscriptions and one with no videos uploaded in 2021. Thus, 12 channels remained in the sample, from which one channel was excluded because the channel owner is not deaf, thus making a sample of 11.

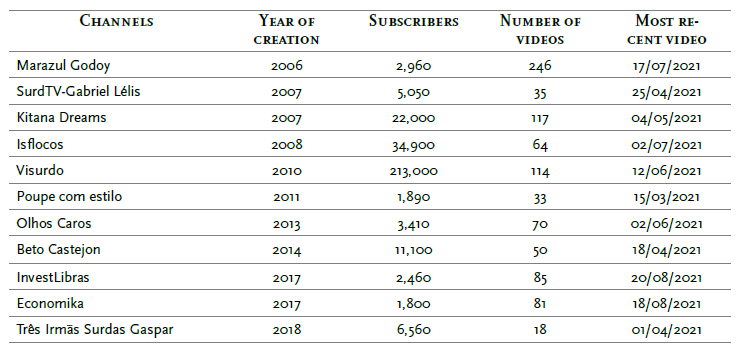

Table 1 and Table 2 show the steps taken in the study and its outcomes, and the path to the sample.

Table 1: Path taken for determining the sample composition according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses method

4. Outcomes and Discussion

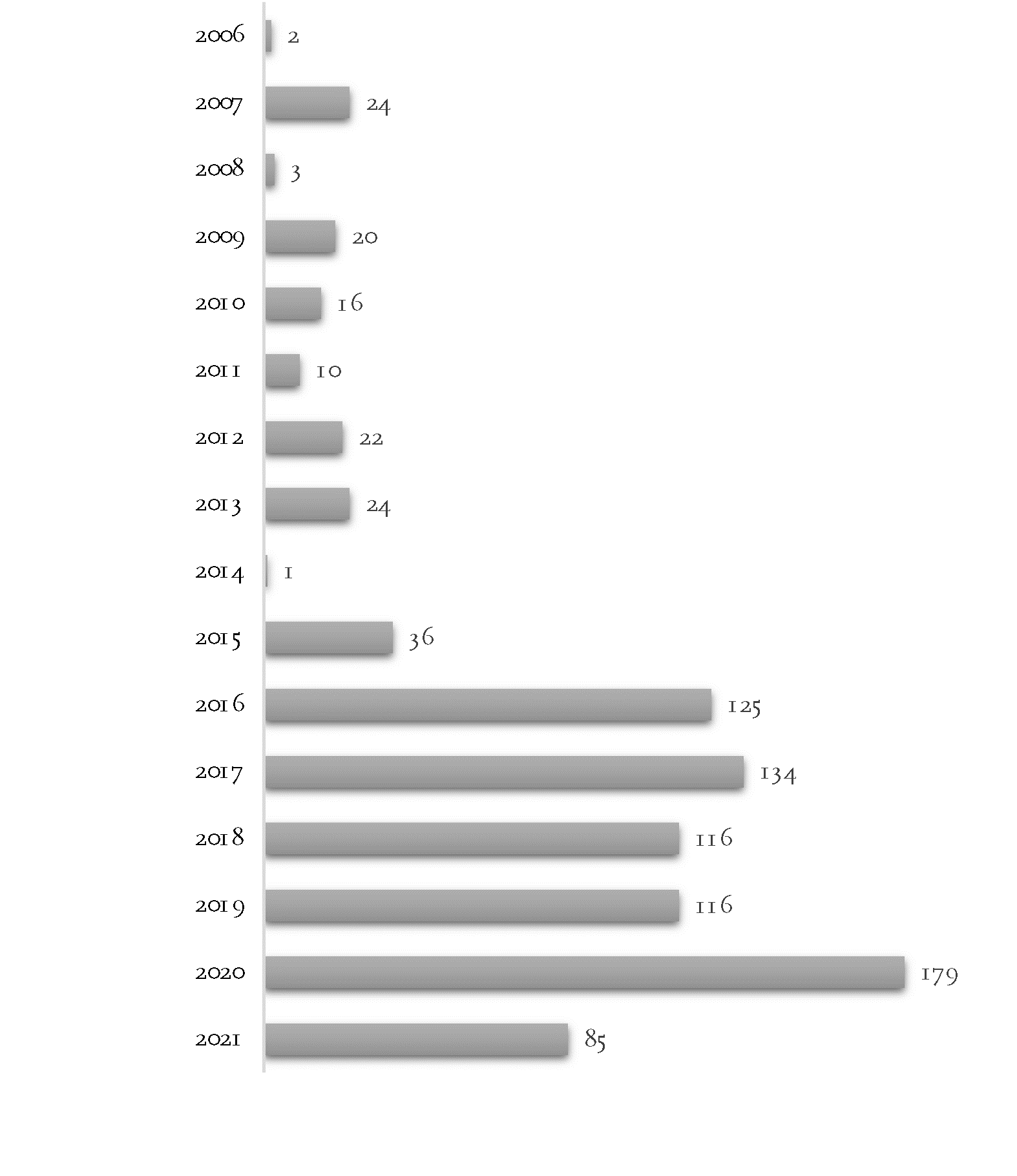

In Figure 1, it is possible to see the number of videos uploaded per year, a total of 913 uploads, considering the channels that made up the sample of this research and covering the period between 2006, the year the oldest channel analysed was created, and 2021. It is worth noting that for the year 2021, the year the data was collected, the sample considered only the months of January to August.

Up to 2014, there was an oscillation in the number of uploads, and 2014 was the year with the lowest number of uploads, with only one uploaded video. As of 2015, there was a considerable increase compared to previous years, and 2020 was the year with the highest number of uploads: 179 videos. Soon after, however, in 2021, the number of uploads decreased, with only 85 videos uploaded, simply because the data collection did not consider the whole year.

In Table 3, one can observe the number of subscribers in each channel, the number of videos uploaded, the year the channel was created and the date of the latest video. Data are ordered by the channel’s year of creation.

Table 3: List of channels of Brazilian deaf people who upload content in Libras with more than 1,000 subscribers and at least one video published in 2021

The channel with the highest uploads has 246 videos and is also the oldest, called Marazul Godoy, and created in 2006. In contrast, the channel with the fewer uploads, called Três Irmãs Surdas Gaspar, was created in 2018 and is the most recent, with 18 videos, although it ranks fifth in the number of subscribers. Adding up the videos from all the channels analysed, we reached 913 videos uploaded between 2006 and 2021 and a total of 305,130 subscriptions.

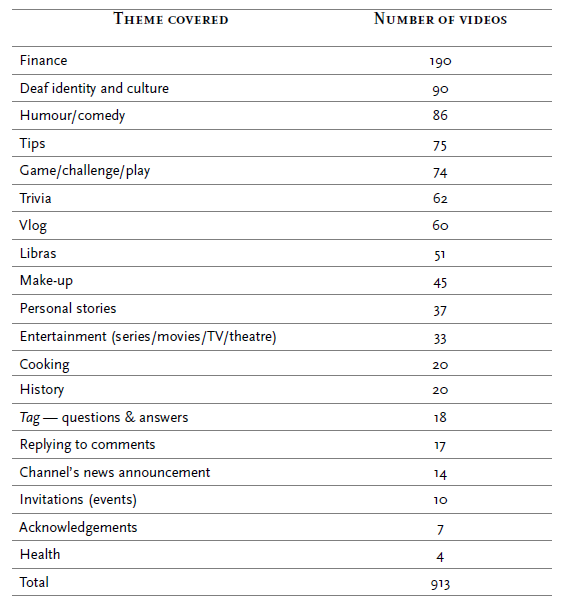

After viewing all the videos of every channel, it was possible to identify that, though each one focuses on some subject or theme, nearly all diversify the themes of the uploaded videos. The only exceptions are the channels strictly focused on financial issues, namely Economika, InvestLibras, and Poupe com Estilo. Table 4 shows the classification of the 913 videos divided into 20 themes.

Because of the exclusive subject in the three channels about finances, this theme stands out among the others, with 190 videos. However, even with the largest number of videos focused on this theme, the most viewed video of this theme has only 11,000 views, a low number compared to the most viewed videos of this study’s sample.

Aiming to verify which video themes are most watched, we selected the videos with over 100,000 views. Among the 913 videos analysed, 24 videos have more than 100,000 views, of which 18 are from the Visurdo channel, three from the Isflocos channel and three from the Kitana Dreams channel. These three channels have the most viewed videos and the highest number of subscribers, as shown in Table 3.

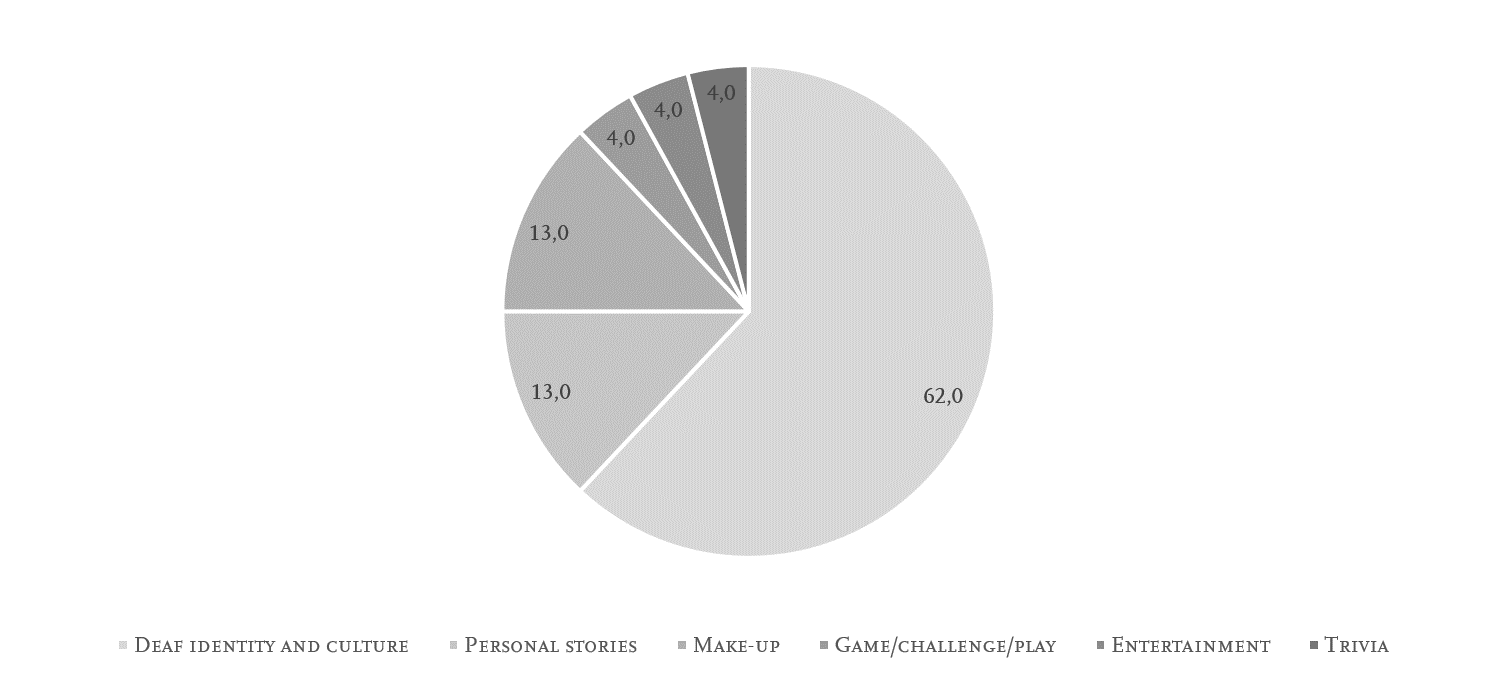

Figure 2 shows how the videos focused on identity and deaf culture take the lead in the views of the most popular videos, accounting for 62%.

The videos on deaf identity and culture, as analysed, have several answers to questions from people who are not part of the deaf community. Some of these issues stand out in the titles of this research’s five most viewed videos: Como É Ter uma Namorada Surda? (How Is It To Have a Deaf Girlfriend?; 2,700,000 views); Como É Ser Surdo? (How Is It To Be Deaf?; 1,000,000 views); Gostamos de Ser Surdos? (Do We Like Being Deaf?; 761,000 views); Surdo É Mudo? (Is Deaf Mute?; 694,000 views); O Surdo Não Pode Fazer… (The Deaf Can Not Do...; 674,000 views). We can assume that this category has more views for non-deaf people’s curiosity about the deaf community. As in Galindo-Neto et al. (2021) research, where the most viewed videos in Libras were bilingual, aimed at all audiences (deaf and non-deaf), it is possible to interpret that the videos produced by Brazilian deaf people with greater access are those that can also reach non-deaf audiences.

Technology is constantly changing, and so are the techniques and strategies to make a video a hit and attract more audience, and YouTube channel owners need to keep up with this change. One of the themes chosen to classify the themes was the vlog1, which is not exclusive to YouTube but has become popular through it. Burgess and Green (2009/2009) define the vlog as follows:

the vlog reminds us of the residual characteristic of face-to-face interpersonal communication and provides an important point of differentiation between online video and television. The vlog is technically simpler to produce - usually requiring little more than a webcam and basic editing skills - but it also provides a direct and persistent approach to the viewer that naturally invites a reaction. (p. 79)

Although some YouTube researchers, such as Amaro (2012) and Coruja (2017), define vlogs more broadly, which would encompass most of the videos analysed in this article, we chose to classify vlogs only the videos that had this title. The vlogs under this theme are videos in which the channel owner mostly shows snippets of travels, events or various moments.

That said, we approached the study of Coruja (2017), in which he discusses the professionalisation of vlog creators who thanks to the possibility of monetisation in the videos based on the number of views, have invested in courses and workshops to improve their content and, consequently, increased audience reach. Nonetheless, even if, in the videos analysed, this professionalisation of deaf YouTube producers is remarkable due to the evolution in image quality, content and editing over the years, less than 2.6% of the 913 videos reached 100,000 views. That might be because, even though YouTube is a democratic space for uploading videos, there is no democratic content distribution to the audience, as explained by Burgess and Green (2009/2009):

if YouTube creates value on amateur content, it does not mean it distributes the value equitably. Some forms of cultural production are accommodated within the preference trends of site visitors and the commercial interests of site owners. Other forms of cultural production are pushed to the periphery of the spectrum because they fall outside the dominant preferences and interests ( ... ) YouTube pushes content with support from other users. While these mechanisms may seem democratic, they have the effect of obscuring minority perspectives. Minority content obviously circulates on YouTube, travelling through various social media outlets to reach its niche audience. However, there is little or no chance that this content will reach a wider audience because of the scale at which YouTube operates. (p. 162)

Thus, considering what Burgess and Green (2009/2009) point out, deaf people, as a minority audience, may be negatively impacted due to the influence of YouTube’s algorithm, affecting the views of those who produce videos in Libras compared to those who produce videos in Portuguese2.

Thus, the study shows that Brazilian sign language also exists on YouTube and is gaining momentum. That is, the number of videos published is increasing, allowing the deaf themselves to show who they are and their language and culture.

5. Final Considerations

This research sought to identify, categorise and analyse the videos produced by Brazilian deaf people recorded in Libras. Throughout the research, we proposed a classification of these videos to understand better what issues have sparked an interest to be shared by deaf people creating content and how the public has responded to the themes published by viewing the videos or subscribing to the channel.

The research data showed a concentration in the number of videos focused on the financial area. It highlighted the views of videos focusing on the deaf identity and culture due to the interest of people outside the deaf community in the unknown since, as mentioned, the contact with deaf people in their daily lives is little or almost none, and the internet is a source of information access.

The tools YouTube provides, enabling interaction between people, and defining itself as a social media, make this digital platform a great place to store and share videos for the overall community. However, as previously stated, the algorithm function does not guarantee the democratic dissemination of videos, and it may end up affecting content creators of less popular subjects, which are not the niche of the great mass.

We can propose new research from the data collected to analyse the decrease in videos uploaded in 2021 since it was the year with the lowest number of uploads since 2016. Whether the factors could be related to the YouTube platform or if the content creators migrated to other more favourable social media to disseminate their content.

This study contributes to the overview of the panorama of the deaf in the wider communicative spaces, such as those identified in the YouTube social media, which, on this platform, the themes clarifying the deaf community itself, its language and its culture have had more acceptance and consumption.

The study’s limitations are worth noting, which may relate to the resources available for searching the videos on the YouTube platform. The platform does not perform searches using users and channel authors’ profiles as criteria (as is our focus in this study: deaf authors) but only by themes. Thus, there may be channels of deaf people that did not feature in the sample. The outcomes also suggest a need for further studies related to reception, design and production, authorship, semiotics and interaction.

REFERENCES

Amaro, F. (2012). Uma proposta de classificação para os vlogs. Comunicologia - Revista de Comunicação da UCB, 5(1), 79-108. https://portalrevistas.ucb.br/index.php/RCEUCB/article/view/3726 [ Links ]

Asensio, M. D. (2018). Las TIC en el aprendizaje de las unidades fraseológicas en FLE: El uso de Youtube et Power Point como recursos didácticos. Anales de Filología Francesa, 26, 27-45. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesff.26.1.352301 [ Links ]

Bernardazzi, R., & Costa, M. H. B. V. da. (2017). Produtores de conteúdo no YouTube e as relações com a produção audiovisual. Revista Communicare, 17, 146-160. [ Links ]

Burgess, J. & Green, J. (2009). YouTube e a revolução digital: Como o maior fenômeno da cultura participativa transformou a mídia e a sociedade (R. Giassetti, Trad.). Aleph. (Trabalho original publicado em 2009) [ Links ]

Carvalho-Lima, K. do S., Oliveira, I. A. de, & Santos, I. B. dos. (2021). Narrativas e representações sobre os surdos em tecnologias virtuais: Análise videográfica no site do YouTube®. Revista Exitus, 11(1), e020134. https://doi.org/10.24065/2237-9460.2021v11n1ID1538 [ Links ]

Coruja, P. (2017). Vlog como gênero no YouTube: A profissionalização do conteúdo gerado por usuário. Comunicologia - Revista de Comunicação da Universidade Católica de Brasília, 10(1), 46-66. https://doi.org/10.24860/comunicologia.v10i1.8128 [ Links ]

Decreto nº 5.626, de 22 de dezembro de 2005, Diário Oficial § 1 (2005). https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ ato2004-2006/2005/decreto/d5626.htm [ Links ]

Festa, P. S. V. (2012). Youtube e surdez: Análise de discursos de surdos no ambiente virtual [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná]. TEDE. https://tede.utp.br/jspui/handle/tede/1494 [ Links ]

Galindo-Neto, N. M., Sá, G. G. de M., Pereira, J. de C. N., Barbosa, L. U., Barros, L. M., & Caetano, J. A. (2021). Information about COVID-19 for deaf people: An analysis of YouTube videos in Brazilian sign language. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 74(1), e20200291. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0291 [ Links ]

Gil, A. C. (2002). Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. Atlas. [ Links ]

Lacerda, C. B. F. de. (1996). Os processos dialógicos entre aluno surdo e educador ouvinte: Examinando a construção de conhecimentos [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Estadual de Campinas]. Repositório da Produção Científica e Intelectual da Unicamp. [ Links ]

Lei nº 10.436, de 24 de abril de 2002, Diário Oficial (2002). https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2002/l10436.htm [ Links ]

Medeiros, F. P. de S., & Rocha, D. de C. (2018). Os canais do YouTube: Uma revisão bibliográfica. In G. M. Ferreira, M. do C. S. Barbosa, & S. Simon (Eds.), Anais do 41º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação (pp. 1-11). Intercom. [ Links ]

Morán, J. M. (1995). O vídeo na sala de aula. Comunicação & Educação, 2, 27-35. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9125.v0i2p27-35 [ Links ]

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Aki, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S. ... Mother, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The Bmj, 372(71), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 [ Links ]

Pinheiro, D., & Lunardi-Lazzarin, M. L. (2013). Produções culturais surdas no YouTube: Estratégias de negociação e consumo de identidades. Revista Educação e Cultura Contemporânea, 10(21), 121-153. http://revistaadmmade.estacio.br/index.php/reeduc/article/viewArticle/334 [ Links ]

Schlünzen, E. T. M., Di Benedetto, L dos S., & Santos, D. A. do N. dos. (2013). História das pessoas surdas: Da exclusão à política educacional brasileira atual [Trabalho de graduação, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlia de Mesquita Filho”]. Acervo Digital da Unesp. http://acervodigital.unesp.br/handle/123456789/65523 [ Links ]

Silva, P. R. M. da. (2011). O impacto do vídeo no ensino do francês língua estrangeira [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Católica Portuguesa]. Veritati. https://repositorio.ucp.pt/handle/10400.14/8538 [ Links ]

Silveira, G., & Amaral, M. (2012, 31 de maio a 2 de junho). Movimento surdo e o ciberativismo através do YouTube e do Facebook [Apresentação de comunicação]. XIII Congresso de Ciências da Comunicação na Região Sul, Chapecó, SC, Brasil. [ Links ]

Sixto-García, J., Rodríguez-Vázquez, A. I., & Soengas-Pérez, X. (2021). Modelo de análisis para canales de YouTube: Aplicación a medios nativos digitales. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (79), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2021-1494 [ Links ]

Strobel, K. (2016). As imagens do outro sobre a cultura surda. Editora da UFSC. [ Links ]

Valiante, J. B. G. (2009). Língua brasileira de sinais: Reflexões sobre a sua oficialização como instrumento de inclusão dos surdos [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Estadual de Campinas]. Repositório Institucional UFSC. https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/190810 [ Links ]

Vinuto, J. (2014). A amostragem em bola de neve na pesquisa qualitativa: Um debate em aberto. Temáticas, 22(44), 201-218. https://doi.org/10.20396/tematicas.v22i44.10977 [ Links ]

1Vlog is a type of blog in which the predominant contents are videos, short for videoblog (video + blog).

Received: August 12, 2022; Accepted: December 01, 2022

texto en

texto en