1. Introduction

Hate speech (HS) is not a specific social media or internet phenomenon. However, a large body of research has provided evidence that, due to user-generated content, HS is quite prevalent online, namely on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok worldwide (Breazu & Machin, 2022b; Rieger et al., 2021). In fact, some studies have shown that the incidence of HS has steadily increased across Europe in the last years (Bakowski, 2022), including Portugal, where this phenomenon affects particularly vulnerable populations and communities such as Afro-descendants, immigrants, and Roma, the latter being the target group most impacted by messages of racism and xenophobia, namely in the Portuguese context (Reynders, 2022; Silva, 2021).

This increase in HS on social media explains why researchers have investigated methods to automate the detection of online HS (Fortuna & Nunes, 2018; Schmidt & Wiegand, 2019). While this might be one way to fight online HS, this approach has some critiques. First, HS is frequently mixed with other subjective concepts, such as “abusive”, “toxic”, “dangerous”, “offensive”, or “aggressive” language, leading to the creation of heterogeneous language resources and tools (Poletto et al., 2021). In addition, most HS detection systems do not consider more complex variables like the social practice, that is, the social and cultural context underlying the production and dissemination of HS (Assimakopoulos et al., 2017). Second, past research has shown that most studies investigate ways to detect overt HS rather than covert forms of hate (Baider & Constantinou, 2020; Bhat & Klein, 2020; Jha & Mamidi, 2017). Covert HS comes out in many forms by exploiting dubious terms to conceal the negative communicative content or technological affordances, such as liking a social media post with a link that redirects to an external anti-immigration website (Ben-David & Fernández, 2016). This phenomenon is also often masked by powerful rhetorical devices, such as irony, sarcasm, and humour (Baider & Constantinou, 2020; Billig, 2001; Dynel, 2018), euphemisms (Magu & Luo, 2018), and rhetorical questions (Albelda Marco, 2022; Krobová & Zàpotocký, 2021), which often rely on a diversity of stereotypes associated with the target groups, making its recognition harder. Although some scholars have related HS with stereotypes (Buturoiu & Corbu, 2020; Chovanec, 2021; ElSherief et al., 2021), research relating both concepts is still scant.

In contrast, overt HS seems more easily recognizable because it usually conveys offensive, aggressive, and explicit discriminatory words and expressions. However, out of context, it is impossible to automatically infer hatred messages based only on the lexicon they convey. As pointed out by Baider (2022), in addition to the locutionary level (i.e., the utterance itself), we need to consider other dimensions of speech acts, namely the illocutionary (i.e., the message holder’s intention) and perlocutionary (i.e., the effect of the message on the target) levels. Although some forms of covert HS cannot be identified as hateful at the locutionary level, this may be changed when considering the illocutionary and perlocutionary levels.

In our study, we will focus mainly on the perlocutionary level since we are interested in understanding the effect of HS on the target groups, taking specifically into account the Portuguese social practice. With this specific goal in mind and taking on a communication perspective, we believe it is crucial to address HS receivers directly to pinpoint the impact of messages (Paz et al., 2020). In particular, we intend to answer the following research questions:

How do the main targets of HS in Portugal perceive this phenomenon?

Which are the most harmful HS manifestations from the perspective of HS targets?

To explore these questions departing from the premises set out in this section, we adopted a qualitative based approach, which relies on the creation of three focus groups (FG) involving the main HS targets in Portugal (Silva, 2021), namely the Afrodescendant, Roma, and LGBTQ+ groups.

As a general contribution, we present qualitative empirical evidence that covert HS is more harmful than overt HS. More specifically, we examine how covert HS can manifest as compliments and humour in Portugal based on the narrations of HS targets’ lived experiences, accounts, and perceptions. While humour has been widely studied in the literature on HS, compliments represent a new contribution to the field and understanding of HS.

2. Background

2.1. Hate Speech

Defining HS is daunting and complex, as there is no universal consensus on pinning down one definition (Brown, 2017; MacAvaney et al., 2019). Following the guidelines provided by the Council of Europe (2022) in its latest recommendation (CM/Rec/2022/16), HS is generically understood as

all types of expression that incite, promote, spread or justify violence, hatred or discrimination against a person or group of persons, or that denigrates them, by reason of their real or attributed personal characteristics or status such as “race”, colour, language, religion, nationality, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity and sexual orientation. (Appendix, Bullet Point 1.1.)

In this definition, there are several central aspects to retain: HS can take on different forms (e.g., verbal vs non-verbal; overt vs covert); the message’s holder has the intention to attack a group or a member of it; and, finally, the idea that the target group is attacked not because of a specific behaviour or action, but because of its identity characteristics or the status it holds in a given social context. In addition to the definition provided by the Council of Europe, it is also worth noting the idea that HS is often anchored in a set of negative stereotypes, used to discriminate against these groups and, thus, reinforce the social distance between the dominant (“in-group”) and the vulnerable (“out-groups”) groups (De Cillia et al., 1999; van Dijk, 1992). This aspect is clear in the definition proposed by the General Policy Recommendation Nº 15 of theEuropean Commission against Racism and Intolerance (2016):

[HS] entails the use of one or more particular forms of expression - namely, the advocacy, promotion or incitement of the denigration, hatred or vilification of a person or group of persons, as well any harassment, insult, negative stereotyping, stigmatization or threat of such person or persons and any justification of all these forms of expression - that is based on a nonexhaustive list of personal characteristics or status that includes “race”, colour, language, religion or belief, nationality or national or ethnic origin, as well as descent, age, disability, sex, gender, gender identity and sexual orientation. (p. 16)

Broadly speaking, the main aspects of these definitions have been recovered in the various existing formal explanations of HS (Brown, 2017; Silva, 2021). For instance, Richardson-Self (2018) summarizes those commonalities as follows:

first, hate speech is often described as characteristically hostile. Second, hate speech is thought to do certain things: silence, malign, disparage, humiliate, intimidate, incite violence, discriminate, vilify, degrade, persecute, threaten, and the like. Finally, hate speech is typically understood as expressive conduct targeting real or imagined group traits. Relevant group traits are commonly taken to include race, religion, sexual orientation, disability, gender status, and (increasingly) gender identity. (p. 256)

Intending to establish our theoretical positioning, we highlight the oppression and social power dimensions that underlie the concept of HS and align our work with studies by van Dijk (1992), De Cillia et al. (1999), Matsuda (1989) and Matamoros-Fernández and Farkas (2021), among others. They have included dominance, social power, discrimination, and control, historical-social oppressions, for example, systemic racism, as a cornerstone aspect of HS as a socio-political phenomenon.

In this article, we focus on the verbal expression of HS, namely the covert forms (as described below), and, first and foremost, the impact these have on the target groups.

2.1.1. Covert Hate Speech

Recent research has argued that “most hate speech today is covert and expresses racism, sexism, homophobia” (Baider, 2022, p. 2353). One explanation for the prevalence of covert HS is the application of the 2016 Code of Conduct that restricts/takes down HS on social media1 (Baider, 2022). As a result, users develop several subtle communicative strategies to spread hate without being noticed and punished.

Overt HS is expressed literally and often includes racial epithets and explicit racist language widely regarded as unacceptable public expressions of racism (Daniels, 2008). On the other hand, covert HS, also referred to as “cloaked”, “subtle”, “soft”, or “implicit speech” (Assimakopoulos et al., 2017; Daniels, 2008), usually uses figurative language and may be understood as a way to disguise messages with racist motives and other types of camouflaged HS. For example, in a contrastive study of Greek and Greek Cypriot online comments, Baider and Constantinou (2020) have demonstrated that specific rhetorical strategies, such as verbal irony and humour, are also effective ways to disseminate covert HS.

Other communication strategies to express covert HS have been identified in the literature, such as “dog-whistling”, a form of symbolic communication involving symbols, keywords, and coded language that has been used to circumvent the censorship/deletion of online HS by automated moderation. According to Bhat and Klein (2020), dogwhistling is a technique used to disguise HS. It conveys messages that appear innocuous to the general public but contain an implied meaning that can only be understood by a specific audience segment (usually a target one). The authors show that this type of covert HS comes out through imagery, memes, euphemisms, symbols, and cloaked language. In this article, we intend to contribute to the body of literature about covert HS, and thus, we analyze two forms of indirect HS, which can be compliments and humour, both anchored in positive and negative stereotypes.

Stereotypes and hate speech. In social psychology, “stereotypes are usually defined as beliefs about groups, prejudice as evaluation of or attitude toward a group, and discrimination as behaviour that systematically advantages or disadvantages a group” (Jussim & Rubinstein, 2012, p. 1). Stereotypes are also defined as generalizations about social groups in which certain characteristics are attributed to all members of a group, disregarding individual differences within the group (Seiter, 1986). As argued by Seiter, in communication research, stereotypes are widely studied concerning media representation (e.g., McInroy & Craig, 2017; Trebbe et al., 2017) and are often understood as discursive mechanisms to maintain the status quo and justify social differences and inequality, serving an ideological purpose (Seiter, 1986).

Although the connection between HS and stereotypes has not been widely explored, some researchers have argued that the use of negative stereotypes should be included in the category of HS (see Haladzhun et al., 2021). In fact, negative stereotypes, including racial ones, are often used in social media to disparage or humiliate the members of a vulnerable community based on fallacious negative generalizations (Paz et al., 2020; Sanguinetti et al., 2018). For example, the main depictions of Roma revolve around the stereotypes of people acting perpetually outside the law, living in dirty and poor conditions, and voluntarily choosing to be dependent on social benefits (Buturoiu & Corbu, 2020).

Social stereotypes have also been studied in the context of online HS automated detection tools, as research has shown that HS classifiers learn human-like social stereotypes (Davani et al., 2021).

In this article, we argue that stereotypes underlie covert HS, especially in the forms of compliments and humour. Articulating our conceptualizations with the stereotype content model provided by Fiske et al. (2002) is key to grounding this main argument. This model proposes that social perceptions and stereotypes form along two dimensions, namely “warmth” (e.g., trustworthiness, friendliness, kindness) and “competence” (e.g., capability, assertiveness, intelligence). Some illustrative examples of the psychological dimensions of group stereotypes formations are offered by Davani et al. (2021):

in the modern-day US, Christians and heterosexual people are perceived to be high on both warmth and competence, and people tend to express pride and admiration for these social groups. Asian people and rich people are stereotyped as competent but not warm. Elderly and disabled persons, on the other hand, are stereotyped to be warm but not competent. Finally, homeless people, low-income Black people, and Arabs are stereotyped as cold and incompetent (Fiske et al., 2007). (p. 6)

Compliments as harmful messages. The notion of conceptualizing compliments as not favourable is not novel. Several past studies in social psychology have focused on understanding compliments as a form of offence for the targets (Alt et al., 2019; Czopp, 2008; Czopp & Monteith, 2006; Siy & Cheryan, 2013). While traditional research has investigated the prevalence of negative stereotypes, more recent studies have investigated how positive stereotypes about marginalized groups lead to stereotypic compliments (e.g., Alt et al., 2019; Czopp et al., 2015). The literature presents some examples of positive stereotypes of social groups: Asians are thought to excel in math ability and African Americans are perceived as athletically superior or having musical and rhythmic ability or social/sexual competence. Understanding how positive stereotypes lead to compliments is crucial for at least three main reasons. First, stereotypes are restrictive because they are based solely on group membership without appropriate individuating formation (Czopp, 2008). Second, research has found that despite their favourable tone, positive stereotypes may have unintended but important negative effects on the targets of such stereotypes (Czopp & Monteith, 2006). Third, positive stereotypes often maintain a complementary relation with more negative stereotypes to ensure that members of target groups can always be disparaged. Women are perceived as warm but weak, Asians as competent but cold, and Blacks as athletic but unintelligent (Czopp, 2008). In fact, Czopp and Monteith (2006) found that people who are likely to praise Blacks for their supposed athletic and musical ability (positive stereotypes) are also likely to denigrate Blacks for their supposed laziness and criminality (negative stereotypes).

What is interesting in the literature about derogatory compliments for our study is the scientific evidence that targets and perceivers understand and appreciate positive stereotypes differently. While targets may find them unacceptable and react negatively, the majority group perceivers (e.g., men in relation to women, Whites in relation to Blacks and Asians) may feel that “favourable beliefs are indeed complimentary because they reflect genuine praise for another group’s ‘strengths’” (Czopp, 2008, p. 414).

In sum, we understand that stereotypical compliments are negative for the targets, because as Siy and Cheryan (2013) argue, positive stereotypes impose a social identity onto their targets and cause them to feel depersonalized, or “lumped together” with others in their social group, by the stereotypist.

Humour and hate speech. Humour is a complex rhetorical device that can be classified into different categories or styles, presenting different functions. Among other styles, the literature has distinguished “affiliative” from “aggressive” humour (Martin et al., 2003). As stated by the authors, while affiliative humour can be seen as a non-hostile form of humour that usually aims to enhance positive feelings and facilitate relationships, aggressive humour typically relies on sarcasm, irony, and satire to manipulate others through an implied threat of ridicule. Affiliative and aggressive humour are among the most prevalent types explored in multimodal content (particularly memes) shared on social media platforms like Facebook (Taecharungroj & Nueangjamnong, 2015). Among the aggressive memes, it must be stressed that racist memes are extremely common in fringe web communities (Zannettou et al., 2018).

Although some researchers have emphasized the positive functions of humour in decreasing social distance between groups, critical scholarship has focused on humour’s disparaging role in ridiculing vulnerable groups perceived as socially and culturally inferior (Breazu & Machin, 2022a). In fact, aggressive humour can be an effective rhetorical device to express covert HS because it is commonly perceived as a joke (Billig, 2001), thus protecting the author from accusations of discriminatory intentions (Woodzicka et al., 2015). Nevertheless, despite some forms of humorous messages conveying HS not being recognized by most users, targeted users may especially be affected by it (Schmid et al., 2022). As shown by Woodzicka et al. (2015), racist jokes are indeed often perceived as racism by the target communities.

Aggressive humour is expressed without considering its potential impact on others, and it is often based on negative stereotypes, with the target being an object of ridicule, not sympathy. Based on a discourse analysis of anti-Muslim and anti-Semitic jokes, Weaver (2013) has shown that stereotypes and inferiorization are combined and used separately to form “acceptable” inclusive images of jokes to mask racism. Those strategies promote the construction of the “out-group” as an inferior social group (Breazu & Machin, 2022a) and contribute to reinforcing and normalizing negative stereotypes associated with the target communities.

3. Methods

This paper takes a qualitative approach to understand how HS targets in Portugal (particularly the Afro-descendant, Roma and LGBTQ+ communities) conceptualize HS considering the Portuguese social practice and how their perceptions and lived experiences could inform the funded research project titled HATE COVID-19.PT, which aims to develop an automatic prototype to detect online HS in European Portuguese. To this end, we conducted three FG, each involving one of the communities mentioned above (n=17) in the summer of 2021. The FG is a suitable method because it will help us to understand the phenomena of HS from the lived experience of target groups, “whose voices are often marginalized within the larger society” (Given, 2008, p. 352).

All the sessions took place online, on Zoom, and were recorded. FG with Afrodescendants took place on May 19, 2021, with nine participants (duration of 03:03:24). FG with LGBTQ+ took place on July 5, 2021, with five participants (duration of 02:28:57).

FG with Roma took place on July 21, 2021, with three participants (duration of 02:01:05). For the sake of organization, participants are cited throughout the article with a “P” followed by a number and the FG they participated in (e.g., P1-Afro; P1-LGBTQ+, P1-Roma).

We aimed to have between six and nine participants in each FG. Nevertheless, this criterion was not accomplished due to several recruitment constraints regarding the LGBTQ+ and Roma participants during the fieldwork timeframe. Specifically, in the case of the Roma FG, we had difficulty finding an ideal number of participants available to volunteer and share their views and lived experiences openly with the researchers. This challenge in engaging Roma participants in qualitative research has been documented by other scholars (Condon et al., 2019). Barriers to recruitment may range from mistrust and fear of harm to cultural beliefs of their community, particularly concerning sensitive topics, which might be the case of HS. In addition, members of this community have faced a history of racial discrimination, persecution and political and social exclusion in Portugal (Cádima et al., 2020; Comissão para a Igualdade e Contra a Discriminação Racial, 2020) and across Europe (Delcour & Hustinx, 2017; Maeso, 2021), which may justify the refusal to participate in qualitative studies that require sharing lived experiences.

4. Procedures

All FG followed the same protocol and were conducted by the same researcher, who self-identifies as a Black female, cisgender, heterosexual, and a migrant who moved to Portugal from Brazil. The FG was transcribed by a master’s student in migration and ethnicities, also a Black woman. This level of self-disclosure is relevant to practice reflexivity, as past research on ethics and the design of new technologies has been emphasized (Bardzell & Bardzell, 2011; Schlesinger et al., 2017). Most importantly, this self-disclosure reveals that the researcher is part of the target communities of HS in Portugal, which contributed to rapport building with the participants. On this note, it is also worth disclosing that the second author self-identifies as a White, cisgender, heterosexual Portuguese woman.

The researcher started by introducing the funded project (HATE COVID-19.PT; https://hate-covid.inesc-id.pt), presenting the research team, and the general goal of the project: to contribute to the analysis and automatic detection of online HS in the Portuguese context. Next, a brief description of the specific project’s goals was made: (a) investigate linguistic and rhetorical strategies underlying either direct (explicit or overt) or indirect (implicit or covert) HS; (b) build a social media corpus to study online HS and closely related phenomena, such as counter-speech, and offensive speech; and (c) develop a machine learning prototype for automatic HS detection.

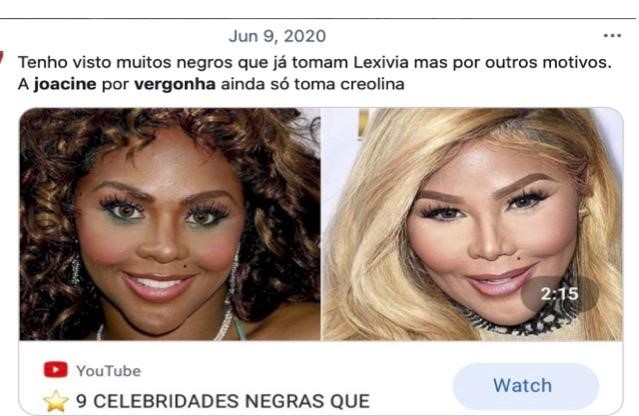

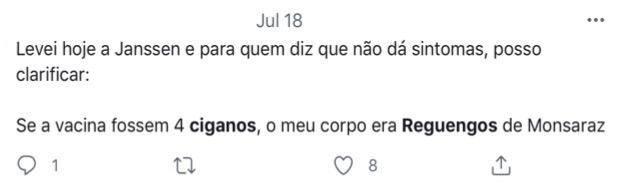

After this introduction, the researcher invited the participants to start the discussion by asking them to identify themselves (regarding social identity) and try to formulate how others perceived them, particularly in the Portuguese context. Next, given the diversity of definitions associated with the HS concept, which can differ according to the area of study, the geopolitical context, and the perspective of the actors involved, the researcher explicitly asked participants to elaborate on this concept, bringing their point of view, and sharing with the group their own lived experience. Particularly regarding overt HS, which often relies on derogatory language, participants were asked to share examples of hateful words or expressions that can be more harmful, according to their understanding. This information could be especially useful to question the use of lexicon-based approaches to identify online HS automatically. In fact, most existing lexica are repositories of offensive, insulting and disparaging words and expressions, which can be interpreted differently depending on their linguistic and pragmatic context; moreover, those resources were not typically subject to validation by the potential target groups those words apply. In regards to covert HS, we tried to understand the target groups’ perspective on this phenomenon, approaching aspects related to its materialization and severity compared to overt HS. Since humour has been pointed out in literature as an effective rhetorical strategy to disseminate HS covertly, the researcher also tried to investigate the communities’ perspectives on this topic. The discussion was accompanied by the projection of illustrative screenshots of tweets containing HS as prompts for the conversation (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Due to ethical protocols, such tweets have been anonymized, and the respective links are not presented.

To finalize this section, it is important to add that all examples and direct quotes provided in the paper were translated from Portuguese into English by the authors, who are both native Portuguese speakers.

5. Participants

Participants were recruited through the research team networks, as they were required to: (a) self-identify as African descent, Roma, or LGBTQ+, and (b) be able to talk about hate from first-hand experience.

5.1. Afro-descendant

All participants self-identify as Black or Afro-descendant. Four are female (cisgender), two are male (cisgender), and three identify as queers, non-normative gender. Ages range from 19 years old to 51 years old. The mean age is 34.8. Almost all participants (n=8) work in the media industry, either in traditional media, like national TV channels, as journalists (n=2), digital media channels focused on Afro-descendants in Portugal as content producers and interviewers (n=3), social media as content producers/influencers (n=1), cinema/theatre as an actor (n=1), or as a freelance journalist (n=1). They all use social media channels to disseminate their work and engage with their audiences. Except for one, who moved to Portugal as an adult (P7-Afro), all participants were either born in Portugal or moved from a Portuguese-speaking country while they were little children.

5.2. LGBTQ+

Participants self-identify as (a) trans woman, White; (b) cisgender male (pansexual), White; (c) queer, Black, and lesbian woman; (d) White, non-binary and non-heterosexual; and (e) non-binary. All participants work in coordinating organizations about LGBTQ+ rights and activism in Portugal. Most have an active presence on social media channels like Facebook and Twitter. The names of the organizations are not mentioned for the sake of participants’ privacy. In this group, ages range from 22 years old to 49 years old. The mean age is 34.6.

5.3. Roma

All participants self-identify as Roma, two are female in their mid-30s, and one is male (22 years old). Like other participants in this study, they are involved in organizations related to Roma activism as cultural mediations in employment centres or education. In fact, they were acquainted with each other.

6. Data Analysis

The FG generated 71 pages of textual data, comprising 38,719 words. To draw out novel thematic findings from this dataset, we used a mixed approach to thematic analysis, meaning that we analyzed data either deductively or inductively. Thematic analysis is a widely used technique for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The main characteristics of this method are the iterative nature of the process, back-and-forth discussions among researchers and literature review. With this in mind, the authors discussed the codes and themes several times. While the data analysis generated several codes and themes, not all added novel perspectives to the scholarship on HS. In this sense, our data analysis was driven by the literature review and the previously mentioned research questions.

First, we familiarized ourselves with the data. The first author, who also conducted the FG, read all transcripts with an open mind, assigning codes inductively to the textual data manually, without any theoretical constraints or specific goals in mind. The researcher iterated this process, looking for specific data points that could respond to the questions asked in the FG, and wrote a summary of each FG to discuss with the second author.

As a second step, we generated codes and themes aligned with the research goals and research questions. Based on the discussion between the two authors, and a second iteration of reading the transcripts and initial codes, the first author inserted all data on NVivo and qualitatively coded the transcripts looking for prevalence across all FG. In this phase, it is worth saying that the “keyness” of our themes was not based on quantifiable measures but rather on whether they captured something important to our research questions (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

In addition, to carry out a mixed approach (deductive and inductive reasoning) to data analysis, we looked for data points that were related to the research project goals, for example, investigate linguistic and rhetorical strategies underlying either direct (explicit or overt) or indirect (implicit or covert).

After this, six overarching themes were decided: (a) covert HS is manifested as a compliment (present in all target groups); (b) humour is deemed as covert HS (present in all target groups); (c) legitimization of HS by mainstream media (non-consensual); (d) online HS is considered more harmful because of its collective dimension and impact (non-consensual); (e) increase of HS due to the increase of the far-right wing parties around in Europe and Portugal; and (f) filtering of words is complex, compromising automated HS detection.

As a third step, we reviewed and refined our themes. We observed that the first and the second themes (a, b) were intimately related because both phenomena are underpinned by stereotypes and are understood by participants as effective ways to hide (covert) HS. We suppressed the third theme (c) because this finding is somewhat represented in the discussion on humour. Although very relevant, the fourth and the fifth themes (d, e) were touched upon by a few participants and did not relate to our research questions. The sixth theme (f) was generated to acknowledge participants’ opinions on the general goal of automating HS detection, but it was taken out because this aspect was not systematically approached nor discussed thoroughly in all FG.

Based on this rationale, the two authors reviewed the themes and memos and, after discussing them concerning the research questions, came up with two final key themes that were the most relevant and received the greatest consensus among the target groups: covert HS manifested as a compliment and covert HS disguised as humour. More importantly, these themes were the most insightful on a theoretical level, revealing how target groups conceptualize HS, namely covert forms. Unlike humour, coded deductively, compliments were coded inductively since this finding was prevalent across all FG. Acknowledging the novelty of addressing compliments as an effective strategy underlying covert HS - an aspect often neglected in HS literature - we decided to analyze this finding in-depth, as follows.

7. Results

7.1. First Theme: Covert Hate Speech Manifested As Compliment

Contrary to what is observed with covert HS, participants in this study have often developed coping strategies to deal with overt HS. On the one hand, overt HS expressions/phrases, such as the ones illustrated in the next examples, are considered daily practices for these participants. They cause a numbing effect or coping mechanism; particularly, participants across the FGs mentioned that they have “gained some protection” (P2-LGBTQ+) or “got used to it” (P3-Roma): “N-word, go to your land” (P4-Afro), “Roma people deserve to die” (P2-Roma), and “you whores!” (P4-LGBTQ+).

On the other hand, when compared to overt HS, covert HS, based on the participants’ lived experiences, may be considered more harmful to the self-esteem and dignity of this group. That is mostly due to the underlying values commonly associated with covert speech messages based on White superiority and structural (or institutional) discrimination. In addition, covert HS makes the target groups feel powerless, as those messages are often disguised or conveyed as compliments which are damaging to the targets. As argued by participants, whenever presented as (an intentional or disguised) compliment, the target of HS messages is disarmed, running out of arguments to defend himself/herself. While the notion of covert HS being more harmful is not always straightforward, our data reveal that participants highlight this difference in intensity. P3-Roma, for example, says:

to me, explicit hate speech is as harmful as covert one. Sometimes the covert speech is worse because we are not expecting it, and we don’t even know why we haven’t been accepted, but it’s just because prejudiced people are behind.

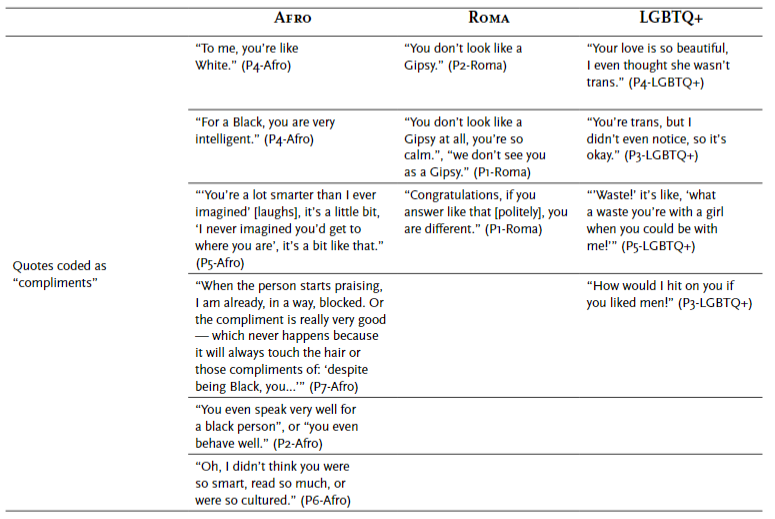

Still, our data reveal that compliments manifest in at least two forms, which are somewhat related: (a) entanglement between nationality and “race” and (b) normativity. The first refers the relationship between the Portuguese national identity and whiteness (Fanon, 1952/2017), which is understood here “as a system of domination that perpetuates the subordination of people defined and identified as non-White by individuals historically identified as White/western within the European society” (Maeso, 2021, p. 29). This contemporary form of racism associated with nationality has also been documented by Kilomba (2018). These new forms of racism, Kilomba says, rarely imply “racial inferiority” as in the past. Rather, they speak of “cultural differences” or “religions differences” and their incompatibility with the national culture.

In this sense, P4-Afro said he often hears from people that he looks “very Portuguese”, which he believes is a code for “whiteness”, since he grew up as an adopted child in a privileged white family. He cited a book called Um Preto Muito Português (A Very Black Portuguese) that can be used to explain how others see him. P4-Afro explains it in his own words: “you are like a White person to me; this is equally offensive; it is a categorization that Blacks are inferior. It’s that thing: ‘I forgot you were Black’ or ‘you, being [despite being] a Black person, are brilliant’.

The second form of covert HS as a compliment was identified through the shared experiences of several LGBTQ+ participants, which enabled us to recognize a pattern in their lived experiences. Many of these stereotypical compliments are considered to fall under the category of normativity, understood here as a system of hierarchy that defines and enforces practices and beliefs about what is “acceptable” and “normal” in a certain social context (Toomey et al., 2012). Participants often said that these stereotypical compliments imply conformity with these social norms, which means that as long as an LGBTQ+ person behaves like a heteronormative person (Toomey et al., 2012), they can be accepted, as the two following quotes illustrate: “what they tend to do most is to praise what is most like the norm over something that is not considered the norm. Those compliments are statements such as: ‘you’re trans, but I didn’t even notice, so it’s okay’” (P1-LGBTQ+). In addition, P4-LGBTQ+ says: “your love is so beautiful [referring to the display of affection of a trans couple], ‘I thought she wasn’t trans’ [a trans person], for example, there are things that people might think of as a form of compliment, but it’s not”.

P5-LGBTQ+ (male who identifies as pansexual) problematizes this as it often implies male superiority and discrimination against women and not only against a LGBTQ+ person. One of the frequent comments they receive is: “you’re gay, but at least you’re a man as you should be”, or “you’re gay, but you’re not a sissy”. Within the LGBTQ+ group, compliments are also manifested in terms of sexual attraction or attractivity, as P3-LGBTQ+ explains: “I also had another situation where a person [a heterosexual man] congratulated me [for my birthday] and said: ‘I would hit on you if you liked men!’”.

Still considering normativity as a form of conveying covert HS as a compliment, this result was also evident in the Roma FG. Among others, anti-Roma stereotypes revolve around criminality, laziness, and receiving undeserved benefits from the State (Sam Nariman et al., 2020). Moreover, the Roma are perceived to be low in both warmth and competence (Grigoryev et al., 2019), dangerous and derogated (Hadarics & Kende, 2019), or even rowdy, dirty and immoral (Liégeois, 2007). Whenever Roma people do not fit the above stereotypes or expectations, almost a social norm in the Portuguese social context, they are usually seen as exceptions.

P1-Roma has already experienced such type of stigmatization at work: “I worked in another place where, when they found out I’m a Gipsy, I heard comments like: ‘you don’t look like a Gipsy at all, you’re so calm’, ‘we don’t see you as a Gipsy”.

In this context, P2-Roma problematizes the idea of being associated with an expected behaviour: “what really irritates me is when they say: ‘you don’t look like a Gipsy’, but why don’t I look like a Gipsy? They are always expecting me to behave in a certain way”. In addition, P2-Roma has also reported that, when politely responding to a random comment on social media, he usually got the following comment back: “congratulations, if you answer like that, you’re different”. P2-Roma reinforces “that’s a form of racism”, which led us to conceptualize compliments as an effective way of spreading covert HS.

To conclude this subsection, we present Table 1, which showcases some illustrative examples provided by the Afro-descendant, Roma and LGBTQ+ participants, respectively, coded as compliments.

7.2. Second Theme: Covert Hate Speech Manifested As Humour

Another thematic finding prevalent across all the groups is that the message of covert HS often takes the form of humour. All groups have agreed that covert HS takes on this format, often in the workplace, on media channels, and online, contributing to perpetuating discrimination against the target groups and the normalization of HS in society. Furthermore, humour is an effective way to invalidate the social identities of marginalized groups. Participants in our study connected all those layers with HS, advocating for ways to develop counter-speech strategies based precisely on humour because they recognize the power of this rhetorical device.

P1-Roma, for instance, conceptualized humour as a disguise for HS, capable of reinforcing negative stereotypes about Roma people, often spread by traditional media outlets. For example, the participant exemplifies how Roma people are usually represented in Portuguese TV shows:

a Roma person is a character dressed in black, with a beard, badly dressed, with a hat and a forced accent. They [media outlets] insist on reinforcing stereotypes and perpetuating what is negative about a Gipsy person. Humour is hate speech in disguise.

Furthermore, P3-Roma stresses the normativity associated with the concept of “black humour”:

I am an activist, volunteer, and part of other groups. In one of those groups, I belong to, I happened to be with a guy who likes dark humour, and while I was there, he held back, but from the moment I left, he told all the jokes he wanted. Black humour is so natural that whoever heard the joke later insisted on telling me. The joke was: “do you know why children with Down’s syndrome cannot marry Gipsies? Because they all have a problem”, that is, Down’s syndrome is a problem, and they associate Gipsies with a problem too.

On the other hand, P4-LGBTQ+ stresses how crucial it is to empower HS target groups, giving them mechanisms to counter covert HS conveyed as humour, considering how damaging it is for the victims, especially in a family context, where people may have close but fragile relationships. To stress the relevance of elaborating efficient counterspeech (a direct response to hateful or harmful speech which seeks to undermine it), P4LGBTQ+ asks: “how do we debunk a joke like this [coming from a relative]?”. In relation to this difficulty in addressing HS in family contexts, P2-LGBTQ+ adds:

on Christmas Eve, or at family funerals, where everyone tells anecdotes about Blacks, about Gipsies, I get very irritated. I always remember a scene in Philadelphia [referring to the 1993 movie directed by Jonathan Demme] when he [referring to the movie’s protagonist who is a gay man] in the sauna with his colleagues, and someone says, “do you know how a gay man fakes an orgasm? Drop a warm yoghurt on the back”, and he shuts up. I think we shouldn’t shut up, regardless of whether we’re LGBT or not. It’s like words; I can take a negative expression or word and turn it into empowerment; for example, queer was a negative term, and jokingly I can say “paneleiro” [a pejorative term in Portuguese, meaning “gay man”], but that’s me.

The Afro-group participants also mentioned several examples of how humour displays HS even in mainstream media, deprecating Black politicians or journalists in Portugal or the workplace. For P4-Afro, several entertainment TV shows in Portugal may function as a way to edify covert HS, as the quote below illustrates:

it is almost inseparable [the boundaries between humour and HS]. Whether opinion, humour, or irony, everything will get mixed up. Rui Sinel de Cordes2, for example, is a Portuguese comedian - let’s call him a comedian -, all he does is hate speech in the form of a joke, against women, against homosexuals, against Blacks, with the following excuse: “I can tell it, I’m on stage. These are not my opinions, these are jokes”, but yes, those are their opinions, just see who Rui Sinel de Cordes’s audience is. He started a whole school of humour in which almost all the comedians are men, White, straight, cis, and they repeat those jokes ad nauseam. It’s not a joke, it’s a repetition of prejudice, only said as punch line. I can say this on television or, perhaps, even Fernando Rocha himself, doing it in a less intelligent way with stereotyped characters like Tibúrcio and Matumbina. It is very difficult to distinguish where the hate speech of its various types begins, that “N-word, go back to your land”, or if Levanta-te e Ri [Portuguese TV show], every night at SIC [Portuguese TV channel] - with Tibúrcio and Matumbina [see Figure 4].

From Fernado Rocha Portugal a Rir 4 - Gago Vendedor, by sancastro007 [@sancastro007], 2011, YouTube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IQBs7ITL18U&t=25s)

Figure 4. The characters Tibúrcio and Matumbina mentioned by P4-Afro appear on the center of this image

In line with P4-Afro, P2-Roma also noted that the abovementioned work of Rui Sinel de Cordes is problematic because “they claim to rebel against the system and oppression, but then they spread hate instead of humour”. Furthermore, as pointed out by P1-Roma, the mainstream media explores negative stereotypes in the mask of humour to perpetuate negative sentiments and hostility towards target groups.

I remembered that they use the term “lelos” [a derogatory Portuguese term associated with Gipsy] a lot to refer to Gipsies. In the TV show Malucos do Riso [Portuguese TV show], they have already used this term. Whenever there is a scene in which they want to represent a Gipsy person, they associate it with a character dressed in black, with a beard, badly dressed, with a hat and with a forced accent.

Although participants view humour as a disguise for HS and a reinforcement of negative stereotypes, they have also noticed the importance of identifying the social identity and the message’s holder standpoint. For instance, P6-Afro, who lives in England, mentions how racialized humorists tell their own stories and how this is entertaining for him, instead of humorists simply repeating and reinforcing stereotypes.

Another thing that I find very interesting is that the humour here [England] is very different from the humour still practiced in Portugal. Here, comedians only make fun of their own experiences; for example, if it’s a Black person, they only make humour about what happened [with them]; they don’t go looking for someone else’s story and make fun of it. Creating humour is telling your own story, but in a funny way, because it’s so ridiculous, it’s funny. I think that’s the kind of humour I like to see.

Conversely, some participants believe that humour created by marginalized individuals can backfire on their communities as it can reinforce stereotypes, as P4-LGBTQ+ explains:

I don’t think they [jokes] should ever be used. Hannah Gadsby [an Australian comedian who explores topics such as sexism, homophobia and related subjects with their sexuality] says in one of her shows that there are so many ways to make a joke that one shouldn’t make it because we are this or that. Other comedians often say: “I am fat, and I always made jokes [about being fat] until I realized that this was a very huge lack of self-love”, or “I am a lesbian, and I always made jokes about being a lesbian, then I started to realize that I shouldn’t do it because it was legitimizing people making fun of me”.

Still related to reinforcing group stereotypes, participants often see humour as very harmful. Our results show that humour perpetuates and normalizes negative stereotypes associated with social identities, such as the Roma, making it difficult for these individuals to find jobs and housing and navigate their daily lives. P3-Roma, being part of one of the most stigmatized ethnic groups in Portugal, distinguishes between the concepts of “hurting” (ferir, in Portuguese) and “detraction” (prejudicar, in Portuguese) to illustrate the difference in using jokes to make fun of marginalized groups in relation to dominant groups.

In addition to common sense - because everyone has their own and it is very dangerous when we leave it up to each other -, what differentiates political correctness from hate speech is when people use these jokes to justify their acts of discrimination and racism against Roma people. Behind a joke that is harmless and doesn’t hurt is the intention. In Portugal, a lot of people make fun of people from Alentejo [region in the South of Portugal], saying they are lazy and don’t like to work, but it’s a joke that doesn’t harm the real life of a person from Alentejo. If a person from Alentejo is looking for work, no one will say: “I don’t give you work because people from Alentejo are lazy”.

In conclusion, all groups agree that there is no clear boundary between humour and HS. As P1-Roma stated: “what is said in hate speech is the same as what is said in humour because prejudice, stereotypes, racism and insults are there; only sarcasm and irony are added”.

8. Discussion and Conclusion

Indirect or implicit hatred messages are often mentioned in the literature as “cloaked”, “camouflaged”, “subtle”, “soft”, or, most commonly, “covert” HS (Baider & Constantinou, 2020; Bhat & Klein, 2020; Jha & Mamidi 2017; Rieger et al., 2021; van Dijk 1992, 1993; Wodak & Reisigl, 2015). All these metaphorical definitions imply the idea of something hidden that needs to be laid bare to be fully understood and, thus, adequately tackled in terms of policymaking or even detection. In this sense, this paper was a research endeavour to bring to light some aspects that can help understand covert HS from the targets’ perspectives.

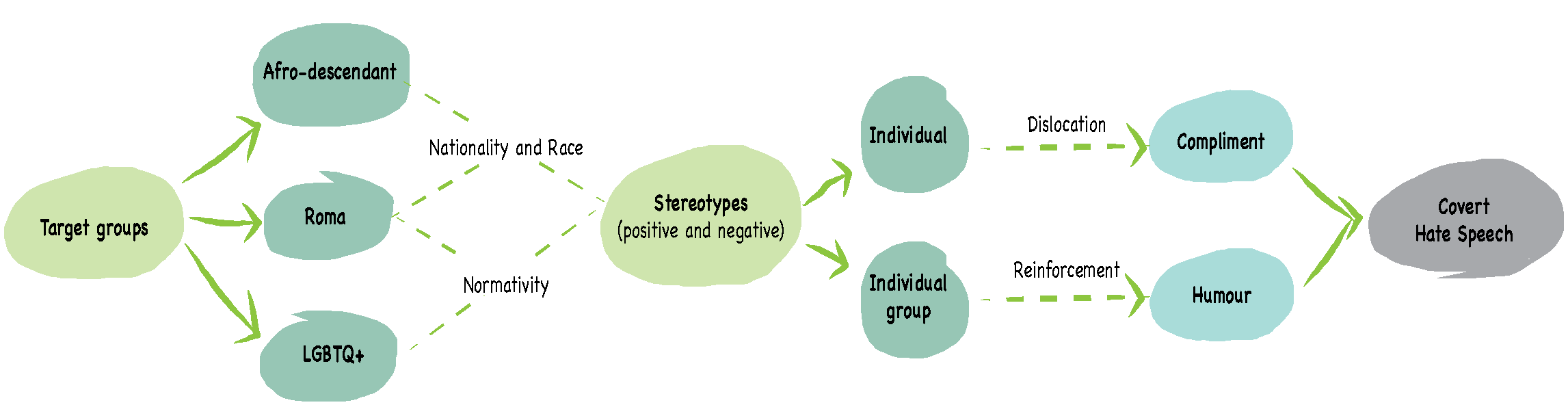

Figure 5 presents a visual representation that summarizes the main research results, in which HS target groups’ perceptions reinforce the idea that stereotypes may be antecedents or serve as the foundation for prejudice (Brigham, 1971). Also, it highlights the conviction that HS detection strongly depends on recognizing social stereotypes (Davani et al., 2021). Although some definitions of HS explicitly include the notion of negative stereotypes (European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, 2020), we argue that positive stereotypes can also edify covert HS. In fact, our findings indicate that compliments are often founded not only on negative stereotypes (e.g., Gipsies are troublesome: “you don’t look like a Gipsy at all, you’re so calm”, “we don’t see you as a Gipsy”), but also positive ones (e.g., physical attractiveness: “‘waste!’, it’s like, ‘what a waste to be with a girl when you could be with me!’”).

Figure 5 Visual representation of the processes underlying the materialization of covert HS based on compliments and humour

While, in the case of compliments, the target (usually, a specific member of a target group) is displaced from the group he/she/they belongs (i.e., the “out-group”) to the dominant group (i.e., the “in-group”), in the case of humour, there is a reinforcement of the (usually negative) stereotypes associated with the target group, which reinforces their position in the “out-group”. The dislocation and reinforcement operations underlying, respectively, stereotypical compliments and humour shaping covert HS, are also represented in Figure 5. In more detail, reading the figure from left to right, the Afrodescendants and Roma participants are connected by dotted lines because both groups share the lived experience that the stereotypical compliment is based on positive stereotypes that are rooted in notions of nationality and “race”. In this context, and drawing on the work of Kilomba (2018), our results dialogue with the provocative question raised by this author: can a non-White person be Portuguese? Or is the non-White person always the outsider, the foreigner outside the nation? For the author, in the scope of the colonial fantasy, ethnicity, skin color or “race” is constructed within specific national limits, and nationality is constructed in terms of “race”. For the participants in our study, covert forms of HS embed this notion brought by Kilomba (2018), such as in the example given by P4-Afro: “you look very Portuguese” combined with “you are like a White person to me”.

Conversely, in Figure 5, the LGBTQ+ group is connected with the Roma target because, for them, the compliment stems from compliance with a certain social normativity (e.g., a gay man who looks straight or a person of Roma ethnicity who appears to be calm). Figure 5 centres on stereotypes as a foundational mechanism that operates at the individual level for compliments and the individual or group level for humour.

It is worth contrasting this finding with the literature, in the field of social psychology, because past studies have shown that “stereotypical compliments” are based on generalizations of positive stereotypes constructed solely on group membership without appropriate individuating formation (Czopp, 2008; Czopp et al., 2015). Our study suggests something different. From the message holder’s perspective, the target deserves to be complimented because they do not fall under the negative stereotypes related to the social group they belong, which detaches (or dislocates) the target from a group position (e.g., “being a Black you are very smart”; “you’re trans, but I didn’t even notice, so it’s okay” or “you do not look like a Gipsy”). From the target’s perspective, such a compliment is harmful because it reveals deep structural oppressions, such as white supremacy or whiteness (Fanon, 1952/2017; Maeso, 2021), contemporary racism (Kilomba, 2018), or heteronormativity (Toomey et al., 2012) that make them powerless and without knowing what to say or react. That resonates with several studies about how targets react when they receive “complimentary stereotypes” and how difficult it is for them to confront or respond to positive stereotypes meant to be a compliment (Alt et al., 2019; Czopp & Monteith, 2006; Siy & Cheryan, 2013).

Like compliments, humour targeting vulnerable or marginalized groups often builds on stereotypes, primarily negative, aiming at ridiculing the group or the individual as a member of that group. However, unlike compliments, which seek to particularize and displace the individual from the group, humour, even when directed at a specific individual, seeks to generalize the stereotype and prejudice associated with their community.

In this sense, the function of humour is to reinforce the stereotype, contributing to its normalization.

Hence, we argue that, unlike affiliative humour (Martin et al., 2003), covert HS explores aggressive humour, typically relying on the use of sarcasm, irony, and satire, aiming at normalizing negative stereotypes, deepening the barrier between those who are in a position of power, and usually appreciate it, and the vulnerable communities, who are simultaneously the objects and the (indirect) receivers of ridicule. It is important to highlight that aggressive humour can have serious implications for the targeted communities, perpetuating discrimination and reinforcing harmful stereotypes, and as such it must be combated, for example, through counter-speech (see Baider, 2023).

Regardless of the intentions of those who produce or reproduce compliments and humour based on either positive or negative stereotypes, the targeted individual or group are strongly affected by the rhetorical force of these strategies, assuming that they can be more harmful than direct HS and inhibit or nullify their ability to respond or react. Although affiliative humour may positively impact individuals, strengthening potential social and cultural bonds, this applies mainly in cases where individuals belong to the same ethnic group (Gogová, 2016) and share the same social identity. In fact, as stated by Holmes (2000), in interactions where the power is particularly unbalanced, humour functions in constructing relationships are often more complex.

Thus, this study highlights the importance of studying the diversity of rhetorical strategies underlying covert HS and reveals the fragility of most current HS detection approaches, which often neglect covert HS in general and compliment and humour recognition in particular, and do not take into consideration the social identity of the target groups (Baider & Constantinou, 2022).

Understanding covert HS as compliment and humour, either online or offline, may have implications on the analysis and detection of HS, which is highly frequent in usergenerated content published either on social media or other digital channels, including mainstream media, in the specific case of humour, as mentioned by the participants of this study.

We conclude this article with the expectation that this investigation will contribute to the development of informed automated HS detection tools, whose performance strongly depends on the ability to recognize complex rhetorical and discursive strategies, such as irony and humour. In addition, this research contributes to the development of future studies in the sense that it points to new lines of investigation because when we retrieve the concept of positive stereotypes, classic in the field of social psychology but little explored in communication, we contribute to conceptualizing covert forms of HS as compliments. This new conceptual articulation significantly contributes to our understanding of covert HS, potentially impacting on the research and the development of automated HS detection systems. Finally, the impact of this study may extend beyond academia by informing the creation of effective conduct policies on social media platforms.

texto em

texto em