Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comunicação e Sociedade

versión impresa ISSN 1645-2089versión On-line ISSN 2183-3575

Comunicação e Sociedade vol.44 Braga dic. 2023 Epub 04-Oct-2023

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.44(2023).4553

Thematic Articles

Local Journalists and Fact-Checking: An Exploratory Study in Portugal and Spain

i LabCom, Faculdade de Artes e Letras, Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal

ii Departamento de Periodismo y Comunicación Corporativa, Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, Spain

A invisibilidade noticiosa a que estão a ser votadas várias cidades em diferentes países faz-nos questionar sobre as consequências para as respetivas comunidades. O desaparecimento de projetos jornalísticos de âmbito local leva a que o vazio deixado possa ser ocupado por outro tipo de realidades, menos comprometidas com o escrutínio dos poderes. A polarização cresce nestes lugares, a participação cívica diminui e isso terá como consequência o empobrecimento da democracia. Porém, estes sintomas podem existir mesmo com cobertura jornalística, quando ela não é feita de forma rigorosa. Neste estudo exploratório, realizaram-se entrevistas em profundidade a jornalistas de 12 meios regionais de Portugal e Espanha, no sentido de analisar perceções e práticas sobre fact-checking (verificação de factos). Os fatores tempo e recursos disponíveis nas redações, quando em número reduzido, são cruciais sobretudo para que se verifique menos. Também registamos o facto de os jornalistas de ambos os países revelarem uma confiança quase cega nas fontes oficiais. Isto gera um déficit no processo de verificação, quando a informação provém dessas fontes. Por outro lado, os políticos locais não só não colaboram, como dificultam o trabalho de verificação dos jornalistas nas redações dos meios locais, com base nos seus próprios interesses.

Palavras-chave: jornalismo de proximidade; jornalistas; desinformação; fact-checking; qualidade do jornalismo

The lack of media attention given to various cities across different countries raises questions about the impact on their communities. When local journalism initiatives disappear, it creates space for alternative narratives that may not be as dedicated to holding those in power accountable. In these locations, polarisation intensifies, and civic engagement dwindles, leading to the depletion of democracy. However, these signs can persist even when journalistic coverage exists if it lacks thoroughness. Through in-depth interviews with journalists from 12 local media outlets in Portugal and Spain, this exploratory study delved into their perspectives and approaches to fact-checking. Time and resources available in the newsrooms, when scarce, lead to less fact-checking. It is also noteworthy that journalists in both countries demonstrate a near unwavering trust in official sources. That creates a deficit in the verification process when information originates from these sources. On the other hand, local politicians refrain from cooperating and actively impede journalists’ efforts to fact-check through local media outlets, often driven by their vested interests.

Keywords: local journalism; journalists; disinformation/misinformation; fact-checking; quality of journalism

1. Introduction

1.1. Local Journalism in the Multiplatform Environment

Local journalism is a form of journalism produced within the community it serves, created by and for the people within that community (Izquierdo Labella, 2010). It requires the existence of a distinct identity rooted in a particular territory and a dedicated commitment from the local or regional environment. A communication pact with a territory that some authors call “proximity journalism” (Camponez, 2002; Jerónimo, 2015)1. Local information feeds this identity, equipping community members with the information required for active participation in that environment. Local media influence the public agenda of small communities, educate citizens about their leaders and different policies and positions and assist in the vital responsibility of holding those public representatives accountable.

However, local information consumption has changed a lot over the past decade, driven by the proliferation of platforms and the fragmentation of information sources (Morais & Jerónimo, 2023; Newman et al., 2021). A similar situation applies to the business models governing local news, which are under great pressure (Wiltshire, 2019). Services traditionally part of the local environment’s value proposition - such as public service information, sports results, weather forecasts, and job offers, among others - are now being provided through platforms and websites of local organisations and companies. Platforms have become dominant in the information market, operating as intermediaries between news producers and consumers, collecting a huge amount of user data and mediating advertising sales. In this landscape, local media compete with entities that also serve as intermediaries for providing access to their own content and are no longer the exclusive providers of public service information. Their advertising model has proved less effective than that of platforms, which have detailed audience data and can offer advertisers targeted and much more specific campaigns.

Mobile access to all types of information, national and international, has also led to a significant decline in citizens’ attention. According to Nielsen (2015), local news is now fighting a battle for attention in a digital landscape filled with myriad content easily accessible through smartphones. There are more and more media and technologies, but less local journalism. Such has been the case in countries such as the United States and Brazil, but also in Portugal, where “news deserts” have been expanding, that is, cities that no longer have any journalistic media or projects (https://www.atlas.jor.br; Abernathy, 2018; Jerónimo et al., 2022; Ramos, 2021). Social media have also prompted the creation of communities around certain topics. Local authorities and businesses use their networks and websites to provide news. These provide people with abundant information about their community outside of traditional media or mediums.

According to Ardia et al. (2020), a shift in how consumers seek information has been evident for over two decades. However, the media industry has been reluctant to change the business model that proved successful decades ago, thereby overlooking innovation policies. In addition to the earlier discussed fragmentation of news and the stagnant progress of newspapers, the conventional approach to handling local-level advertising has been supplanted by precision-targeted advertising overseen by major players like Facebook or Google. This shift has resulted in the detriment of the local media business. The option they provide to local advertisers to target their message recipients and optimise their investments has supplanted the conventional newspapers, radio, and television offers. These traditional mediums used to be the only channels for reaching the public. Platforms have very specific data on different audiences’ tastes, preferences and needs, something of enormous value to advertisers that the media cannot offer (Morais & Jerónimo, 2023). “Local news organisations, which do not have the data, cannot offer the same level of targeted advertising” (Ardia et al., 2020, p. 13). Furthermore, as acknowledged by editors of local media themselves, sharing their news on platforms leads to the dilution of the news brand (Bell et al., 2017).

However, it is not just about one outdated business model being replaced by another. According to a study by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, co-published by Blanquerna University, the larger issue is that social platform structure and economics incentivise the spread of low-quality content over high-quality material (Bell et al., 2017). “Journalism with high civic value - journalism that investigates power, or reaches underserved and local communities - is discriminated against by a system that favors scale and shareability” (Bell et al., 2017, p. 4). According to the authors of the same report:

technology companies including Apple, Google, Snapchat, Twitter, and, above all, Facebook have taken on most of the functions of news organizations, becoming key players in the news ecosystem, whether they wanted that role or not. The distribution and presentation of information, the monetization of publishing, and the relationship with the audience are all dominated by a handful of platforms. These businesses might care about the health of journalism, but it is not their core purpose. (Bell et al., 2017, p. 8)

In the new digital ecosystem, publishers have lost control over the distribution of information, which is at the discretion of the algorithm used in each case by a given platform. Thus, they have the power to make an agency or medium more or less effective in disseminating and distributing its news. They are the new gatekeepers and decide what is or is not relevant to a previously segmented demographic. However, platforms do not prioritise addressing the problem of disinformation/misinformation or the informational configuration of local identity.

1.2. Local Media, Disinformation/Misinformation and Fact-Checking

The pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation process in which the regional press has been immersed for decades, forcing it to undergo a transition that was not deemed a priority in some countries (Galletero-Campos & Jerónimo, 2018). Meanwhile, journalists’ professional routines have been changing to prioritise digital editions. In many European countries, newsrooms have established new dynamics, roles and processes to meet the needs of the digital audience (Jenkins & Jerónimo, 2021).

However, the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has also seriously damaged the sector. In the United States, a massive number of newspapers have closed (Ardia et al., 2020). In the last three years alone, 360 newspapers have closed (Edmonds, 2022). In Portugal, the Journalists’ Union raised concerns about the worsening state of the regional press, as numerous newspapers suspended publication during the pandemic, following years of precarious existence (Jerónimo & Esparza, 2022). The same situation was experienced in countries such as Brazil. In Spain, media enterprises have chosen to implement Temporary Employment Regulation Files since the onset of the pandemic. These measures, endorsed by the Government to aid company sustainability, have resulted in salary reductions and reduced working hours. Remote work has additionally led to staff relocation, with journalists frequently working via phone and remotely, often distant from where news is produced.

Paradoxically, the pandemic has sparked an increased demand for information on news organisations’ websites, even as these same companies have experienced significant revenue losses from events, advertising, and newsstand sales. In countries like the UK or Portugal, the public sector had to support the industry economically, notably local media (Sharma, 2021).

The shrinking of the industry and the disappearance of local newspapers are leaving many territories without outlets to engage in public debate on issues of local concern. Abernathy (2020) demonstrates in the report News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive? that the pandemic has exacerbated the trend. In the case of the United States, over 1,500 out of the 3,031 counties are served by only one local newspaper, in most cases, a weekly publication. Over 200 of these counties have no media at all. Moreover, rural communities that have lost their local newspapers lack good broadband coverage, making it difficult to access information online easily.

In Spain, the provinces of Guadalajara and Cuenca in Castilla-La Mancha have witnessed the closure of their local newspapers (Galletero-Campos, 2018). Within that community, the percentage of the population that reads newspapers stands at a mere 7% (Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación, 2018). Of the three provinces that make up the autonomous community in Aragon, two - Huesca and Teruel - also lack a local media outlet (Galletero-Campos, 2018).

In Portugal, during the pandemic, in 2020, the number of municipalities without any media registered with the Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social (Media Regulatory Authority) was 57 (18.5%; Ramos, 2021). Meanwhile, this figure has increased - to 61 in 2021 (19.8%) -, prompting even the public involvement of the Associação Portuguesa de Imprensa (Lusa, 2022). The association raised concerns about the challenges arising from the information void, including the propagation of disinformation/ misinformation. A more recent study (Jerónimo et al., 2022) reported that 166 of the 308 Portuguese municipalities (53.9%) are at some level of risk: categorised as deserted (devoid of any media outlet), semi-deserted media presence with sporadic coverage) or threatened (solely relying on one media outlet). This mapping only considered journalistic media and did not include other media types produced through citizen initiatives, excluding journalists’ involvement. While acknowledging the potential presence of such realities within any territory within the identified “news deserts”, they were not analysed. Nevertheless, Jerónimo et al. (2022) suggest further studies to explore how populations living in “news deserts” get information. That could also help to identify what kind of media are active in these territories.

The decline of the local press renders communities seriously vulnerable. Resources and reliable sources of local information are scarce commodities. Information is increasingly consumed through social media, where disinformation/misinformation easily proliferates. “In the vacuum left by the disappearance of local news sources, users are increasingly reliant on information sources that are incomplete, and may in fact be misleading or deceptive” (Ardia et al., 2020, p. 21).

As observed, platforms do not prioritise addressing the issue of disinformation/ misinformation. They have sought assistance from authorities in this domain, believing they have no right to act as mediators of truth. Nevertheless, they did not want to stand still concerning an issue significantly undermining their credibility. So far, they have implemented content moderation measures by hiring the services of external technology consultants to remove toxic content (Satariano & Isaac, 2021). Additionally, they have partnered with fact-checking organisations as part of their third-party fact-checking program to combat “fake news”2. In 2018, Facebook launched the Accelerator project within the Facebook Journalism Project. The goal is to empower local news publishers to make their business model sustainable by enabling them to build online communities and increase their revenues from digital readers3.

Interest in disinformation/misinformation has been on the rise within academic and institutional circles over the past decade (Said-Hung et al., 2021). However, the truth is that little has been studied and debated regarding the impact on the local public sphere (Torre & Jerónimo, 2023) and local media (Alcaide-Pulido, 2023; Jerónimo & Esparza, 2022). However, the effects of disinformation/misinformation are most keenly felt at a grassroots level, particularly on the local scene. The lack of journalistic scrutiny on matters influencing community life impacts local economies and shapes citizens’ perspectives promptly (Fernandes et al., 2021).

The fight against disinformation/misinformation depends, to a large extent, on the vitality of local journalism (Radcliffe, 2018). In small communities, local media journalists are the only journalists citizens see on their streets or towns. Trust is cultivated through close interaction and connection between the two. And forging this trust represents the biggest challenge for local journalism. A report from the International Press Institute underscores the significance of trust between citizens and journalists (Park, 2021). It drew insights from focus groups comprising over 35 journalists, editors, media managers, and entrepreneurs at the forefront of media transitions, fostering new perspectives in local media across Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. The report analyses the cases of new digital start-ups and transitioning traditional media outlets in Ukraine, India, Zimbabwe, Peru, South Africa, Mexico, Venezuela, Paraguay, Kyrgyzstan, Israel, Palestine, Hungary, Jordan, Pakistan, Argentina and Guatemala. It focuses on links with local communities as the biggest opportunity for the future of local media. As the same report proves, the sustainability of local media requires their consistent ability to showcase their value to the communities they serve. That should be the main objective of the local press, to showcase through its work that it is on the same side as its community, thereby building a special relationship with its audiences.

As validated by the most recent Digital News Report (Newman et al., 2022), the local and regional press is positioned among the information products that citizens have the highest level of trust in, even amid the widespread erosion of trust in news media overall. Furthermore, considering the overall decline in citizens’ engagement with news, the study underscores that 63% of respondents are interested in local news. Respondents also display interest in pandemic-related information (47%), international news (46%), culture (44%), science and technology (42%), politics (41%), environment and climate change (39%), security (37%), lifestyle (36%), health (35%) and sports (33%).

Citizens’ enduring trust in and appreciation of local information persists over time, even amidst the discredit and waning interest registered in other subjects. Local media should harness and capitalise on this valuable asset. Their decline pertains to their business model rather than their credibility. That is where their main opportunity lies: fighting disinformation/misinformation can serve as a means to bolster citizens’ confidence in the local press’s role in this domain. Local media play a key role in the disinformation/misinformation war and can be demonstrated by regular verification, conducting in-depth reporting and exposing propaganda and misleading information (Jerónimo & Esparza, 2022).

One approach to address this challenge has been the emergence of fact-checking initiatives, primarily focusing on external verification, as internal fact-checking is typically carried out within newsrooms (Graves, 2016, 2018). The European Commission also expressed concern, allocating €11,000,000 in funding in 2021 for eight academic hubs and collaborating with other partners associated with the European Digital Media Observatory. The possibility that the public, that is, non-professionals or laypeople, can participate in fact-checking should not be overlooked (Allen et al., 2021). Considering the limited resources usually available in local media and the strong interest and civic engagement of certain citizens towards media, it is clear that they can play a role in the verification process as allies of journalists (including individuals with expertise in technology or other subjects that may lie outside the journalists’ domain).

Fact-checking or verification involves the processes and practices of validating the accuracy of specific information that circulates through various media channels, including social media, rumours, or statements made by public figures. In today’s digital ecosystem, disinformation/misinformation content is widely shared. Therefore, the verification process has become the primary responsibility of numerous journalists, even evolving into a specialised field due to the need to use advanced tools and methodologies. There are journalistic organisations solely devoted to fact-checking projects. The reality of local media is very different, as the lack of human and technical resources is a determining factor. Nonetheless, journalists employed by these media outlets also adhere to a verification process in their daily workflows, which involves checking whether the information they receive is true. They fact-check, however, at a less specialised level and before publication. That is the process we will refer to in this article when addressing the journalists’ fact-checking activities. When undertaken as part of specialised projects, it is done after the fact (e.g., statements, social media posts, etc.).

It is also worth mentioning that just as users have the potential to amplify the impact of disinformation/misinformation content, they also hold the capability to assist in identifying and rectifying rumours, thereby collaborating with the media and journalists (Jerónimo & Esparza, 2022; Park, 2021).

2. Methodology

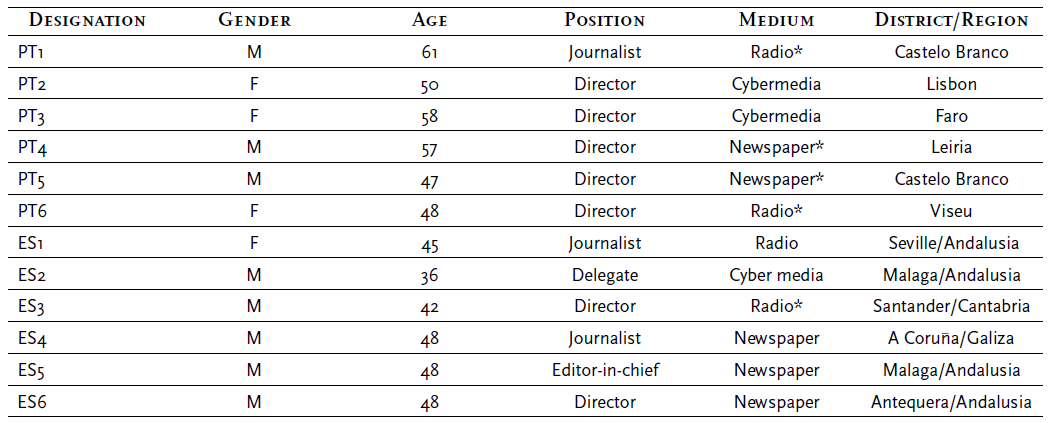

This exploratory study sought to assess how local media journalists in Portugal and Spain perceive and conduct fact-checking in the context of growing disinformation/ misinformation. To this end, 12 semi-structured interviews were conducted with journalists with and without editorial responsibility in their respective newsrooms (Table 1). These interviews were all conducted online (via Zoom) between November 16, 2021, and March 18, 2022.

Table 1 Data on the journalists interviewed

Note. M (male) and F (female); *publishes in traditional and online formats

There was an effort to ensure diversity not only of the interviewees’ gender but also of the nature and geographical origin of the outlets for which they worked. While complete achievement was not feasible, this objective was more successfully fulfilled in Portugal than Spain. The interviews, with a script of 22 questions, lasted 24 to 61 minutes. They focused on working conditions, content, sources and routines (including fact-checking), biases, and efforts to fight disinformation/misinformation. For the scope of this article, these interviews were used to: potential shifts in newsroom journalist numbers attributed to the pandemic; document journalists’ perceptions of the evolution of disinformation/misinformation and the fact-checking process; document journalists’ perspectives on any differences in the fact-checking process in traditional and digital media and, if so, the reasoning behind these differences; document journalists’ viewpoints on fact-checking information from official sources, other media, fellow journalists, as well as social media users.

3. Findings and Discussion

The ongoing impact of the pandemic, which has ushered in numerous transformations in the structure of organisations, led us to investigate the developments within the newsrooms of local media outlets in Portugal and Spain. Thus, we noted that the pandemic did not bring changes in most cases; the number of journalists remained unchanged before and during the pandemic. On average, the sampled newsrooms comprised 7.6 journalists in the Portuguese case and 9.5 journalists in the Spanish context. This is one of the most relevant data collected from the interviews and reflects an image of resilience acknowledged in this sector, particularly in Portugal (Jerónimo, 2015). In this country, we find the only exception in the study: a newspaper’s newsroom with an online presence with a staff of 12 journalists before the pandemic experienced a reduction to nine at the pandemic’s onset and further decreased to five afterwards. Nevertheless, the departures were not prompted by redundancies or layoffs but by professional decisions. Among the seven cases, two journalists transitioned to another media outlet, so they remained in the profession, while the rest “realised with the pandemic that they wanted to change their lives” (PT6).

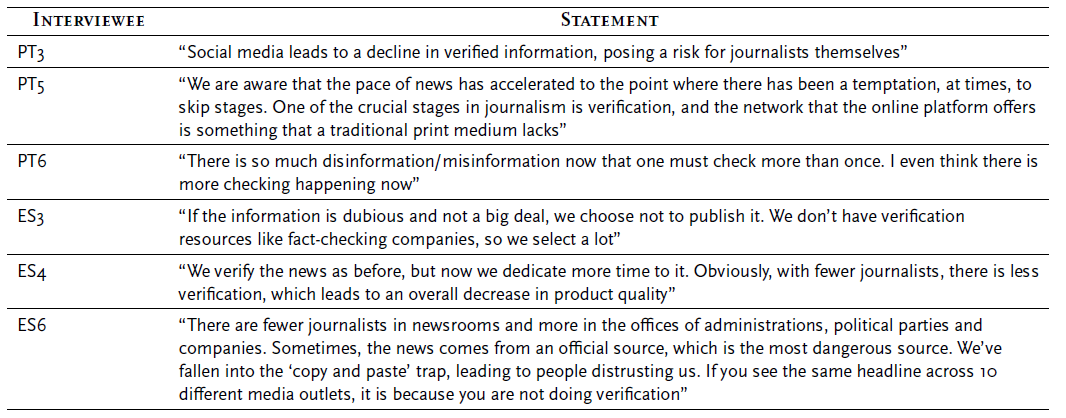

Overall, the blame for disinformation/misinformation is attributed primarily to social media, leading journalists in Portugal to emphasize the need for more fact-checking (Table 2). Furthermore, most respondents recognise the challenge of rapid and extensive publishing as a significant factor contributing to errors.

On the other hand, journalists in Spain take verification as part of their daily work. Given the shortage of people, some local media outlets choose to refrain from publishing certain topics, particularly those they consider dubious. In such cases, they focus on developing unique and distinct content. We observed that Spanish local media are more selective to avoid errors. They consider the pressure of immediacy inherent in the digital environment and social media an impediment to thorough verification, thereby enabling the spread of inaccurate or biased information. Most of them also approach information from official sources with scepticism.

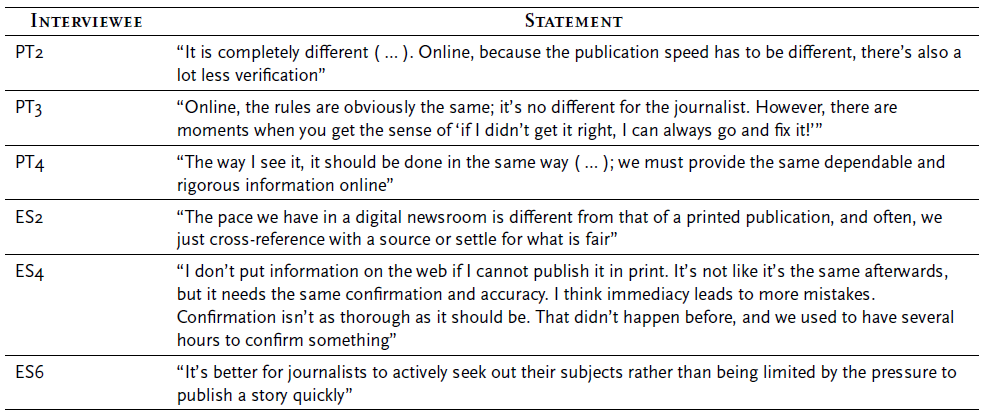

The journalists were divided when asked whether the verification was the same for publishing in traditional or online media (Table 3). This is evident among the Portuguese interviewees. While some perceive variations in verification methods, particularly in terms of time invested and quantity of sources used, others contend that there is no difference and advocate for a similar verification approach. In the latter scenario, we can see that the journalists mean rigour - meaning the time and resources invested by journalists should yield equivalent outcomes, regardless of the medium used for delivering the news.

Regarding the Spanish interviewees, there has been a shift in the dynamics of news production: newsrooms now focus more on the digital environment, aiming to enhance the quality of information. In this sense, it is apparent that journalists are engaging in a learning curve, particularly in their intention to avoid repeating past errors spurred by the pressure of immediacy. In certain instances, it is noticeable that the media outlet’s reputation is given precedence, manifested through a focus on original topics and more in-depth content, rather than solely pursuing breaking news that might lack proper verification.

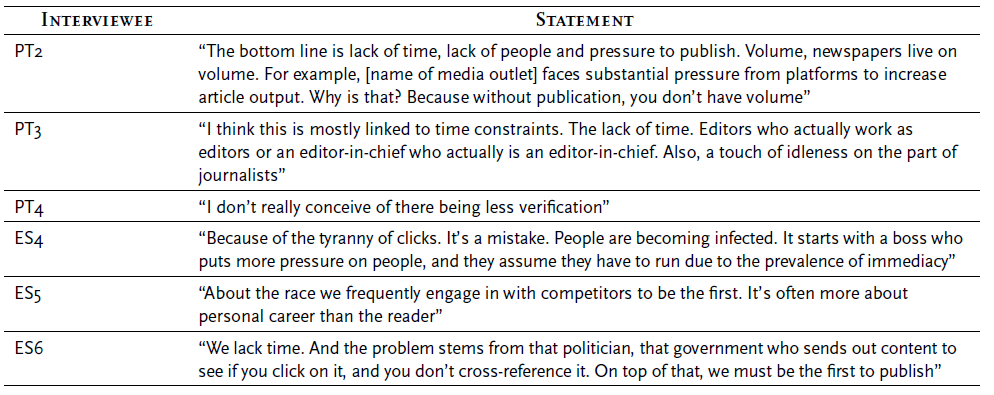

The emergence of fact-checking projects was partly a response to the recognition that the process of information verification within journalism and newsrooms was not meeting expectations. We asked our interviewees to identify possible reasons for this phenomenon (Table 4).

Among Portuguese journalists, time emerges as the primary critical factor. We also highlight one answer, which identifies two problems: (a) journalist versus content producer, and (b) the new generations of journalists.

I think people perceive journalism as content creators. There’s pressure to incorporate specific keywords in the headlines. I think many view themselves primarily as content creators. I have this discussion a lot here in the newsroom. Sometimes, it’s more about quantity than quality because the way journalism is thought of now, among this generation working with me, which is mostly young, is with this idea. It’s all much more ephemeral, it’s all much more “we have to publish now”, “we have to do it nicely, we don’t have to make nice good”. (PT6)

Some also point to the big platforms and the need to generate volume, in other words, to publish a lot of news (Morais & Jerónimo, 2023).

On the other hand, Spanish journalists do not seem to have different views on immediacy and time pressure. There is apparent consensus that the local media have also entered the race to publish first and fast to get more clicks and generate more website traffic (Jenkins & Jerónimo, 2021; Jerónimo, 2015). This competition causes tensions within newsrooms, hastens news preparation, and means that some of it is not verified as it should be. There is also the notion that incorrect information published online can be swiftly corrected or that news pieces can be enhanced or supplemented promptly. This dynamic fosters a certain sense of tentativeness in what gets published.

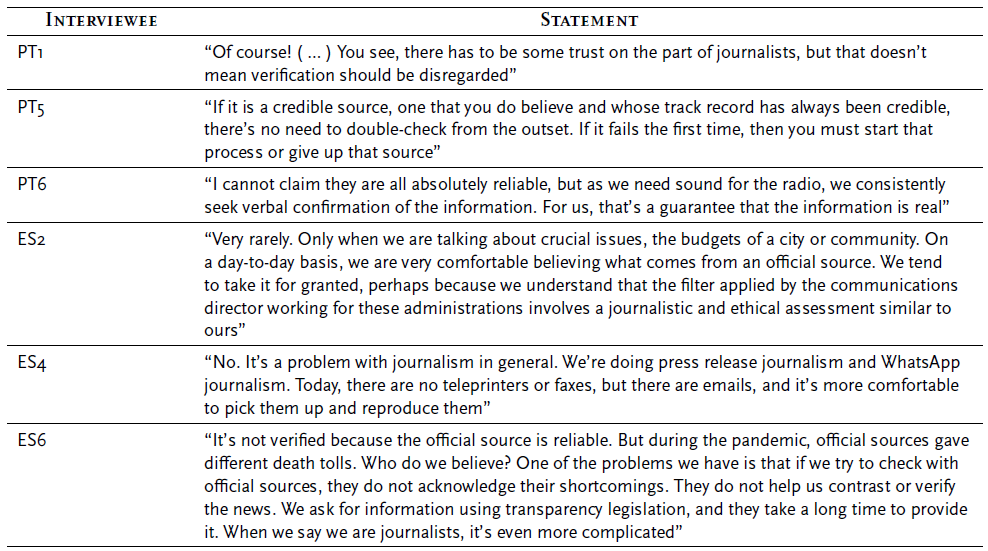

A trust-based relationship between journalists and their sources is essential for exercising their profession. This trust may or may not be decisive in the verification process. Thus, we wanted to investigate whether journalists verify information from official sources (Table 5). In Portugal, as a general rule, journalists typically refrain from doing so. The main reason for this is the trust placed in official sources. However, it is also acknowledged that this is built up over time and that if there is a breach of trust or, on the other hand, the subject matter is sensitive, there will be verification or more verification than usual. In Spain, official sources also enjoy absolute credibility as their information is not verified. The practice of journalists being mere recipients of official releases or notices or publishing politicians’ statements without context or counterpoint (Jerónimo, 2015) has turned some media outlets into vehicles for promoting biases, inaccuracies, or mistakes.

Interacting with sources and validating the information they provide is part of journalists’ daily routines. Nevertheless, there are different types of sources, and the relationship may differ. Having explored how local media professionals in the examined countries manage data from official sources, we sought to gain insight into their approach toward content originating from (a) other media outlets and journalists and (b) users on social networks.

The track record of the media and news authors explains why some of the interviewees in Portugal do not view all sources equally. Some are considered more trustworthy than others. On the other hand, when it comes to news disseminated by other media outlets and/or journalists that might lead to fresh stories or new angles, there will always be verification.

If a media outlet is reliable, it is indeed reliable! But we also have to consider the scale of what is being reported and even the impact it will have. While, on the one hand, in certain situations, it’s enough to quote the media outlet and include a few excerpts, building the news ourselves, on the other hand, if we see that it’s something very impactful, for example, on the public, we can and we should. (PT1)

In Spain, the interviewees mostly reverify, cross-referencing news from other media outlets and/or journalists. They also emphasize that their confidence in externally published information hinges on their understanding of those sources’ professionalism or lack thereof. “We are much more critical of fellow journalists than institutions and administrations due to the drive to excel and do things differently” (ES2). Depending on the credibility and standing of the editor, Spanish local media outlets appear to choose between directly citing or independently sourcing information.

Using content published on social media by users or sharing it on the media outlet’s own profiles or pages is something that has already been studied in local media (Amaral et al., 2020; García-de-Torres et al., 2011; Said-Hung et al., 2014). In the current study, focusing on the Portuguese sample, viewpoints are split. While some participants disregard social networks entirely, others do not ignore their content. Furthermore, distinctions in practices between professional and personal usage are evident. In the professional sphere, what other users share on social networks can occasionally serve as a basis for journalistic work within the newsrooms of media outlets where the interviewees are employed. In contrast, in their capacity, the position of journalists is more extreme, as they decide whether or not to publish content created by others.Trust in the source’s credibility plays a pivotal role in these dynamics.

Certain facts unfolding on social media and reported there lead to an “investigation”. Now, transcribing or posting a story you see on a profile of someone you simply don’t know does not happen. Even when we know the person, we pick up the phone or email them so that they can tell us, and not on social network. (PT5)

As for the Spanish sample, the notion of learning from mistakes resurfaced. While in the first phase of using social networks, they were perceived as a rapid means to access sources and street-level events or to gauge public sentiment (García-de-Torres et al., 2011), journalists now realise that these networks can propagate virtually anything, particularly content designed to manipulate or disseminate disinformation/misinformation. Several acknowledge the journalist’s role as a gatekeeper, responsible for sieving through information, in contrast to social media user profiles. “Do we let someone who isn’t a nurse or doctor vaccinate us? The same applies to journalism. Today, everyone is chasing clicks and followers” (ES6). Some highlight, using examples, the potential consequences for the local media’s credibility in the population’s eyes when they opt to include user-generated content without proper verification.

An incident involving an atypical heavy snowfall in a Spanish port town comes to mind. An image was shared through WhatsApp, and while certain media outlets took the time to verify that it was an old photograph, others promptly published it as breaking news. “That really prompted us to take note and be cautious from that moment on about what came through social media” (ES5). The same happened during the pandemic, with images of wild animals supposedly invading some areas of the city which were fake.

The subpar quality of the information that is sometimes published in the regional press, which has been analysed in previous studies (Rivas-de-Roca, 2022), is directly related to the subordination and lack of detachment of certain sources. This problem becomes even more pronounced when it comes to institutional sources. The journalists interviewed do not subject these sources to thorough scrutiny; instead, they rely on the communication strategies outlined by the local and regional authorities’ press offices. The precariousness of the local media and the excessive dependence on official information lead journalists to overlook or inadequately verify information from these organisations. This can result in the dissemination of inaccurate or uninformative content.

Recent research on the performance of local media in Spain and Portugal indicates that journalists recognise the need to refrain from overusing these official sources and engaging in so-called “declarative journalism”. Instead, they prioritise generating original content as a distinguishing factor that shapes the quality of their work and the service they provide to their audience (Alcaide-Pulido, 2023; Rivas-de-Roca, 2022).

Hence, incorporating verification practices, including official information, should be part of the daily routine for local media journalists, especially considering the high susceptibility to disinformation/misinformation within urban contexts (Alcaide-Pulido, 2023). Nonetheless, many journalists perceive verification as an enduring element of quality journalism (Couraceiro et al., 2022).

4. Conclusion

This study underscores certain factors that impact the operational dynamics of journalists working in local media across Portugal and Spain, ultimately impeding their ability to fact-check the information they receive effectively. Firstly, two external factors impede journalists from effectively conducting verifications: time limitations and a shortage of personnel to perform the task optimally.

Verification is part of their daily work routine for most journalists interviewed, whether in Spain or Portugal. In order to engage in thorough journalism, it is essential to validate the accuracy of all incoming information from various sources, whether official or from community groups and associations. Nevertheless, the time constraint and the urgency brought on by digital editions and click-based priorities, coupled with the aspiration to be the first to publish and garner feedback on social networks, accelerate the publishing process and hinder comprehensive information verification. Time becomes even more scarce when there are not enough people to manage the considerable volume of information that requires publication. The downsizing of these media organisations over the past 15 years has prevented cuts during the pandemic. With the same level of resources in newsrooms but increased public demand for information, crucial steps are overlooked, leading to reduced verification efforts and a decrease in the number of sources used. Effective fact-checking cannot be accomplished without adequate time and personnel.

In addition to external factors, there are internal or subjective factors related to journalists’ own attitudes, which affect how they verify information. Thus, excessive reliance on official sources, sometimes combined with sloth - as Portuguese journalists admit - means that the local media in Portugal and Spain do not check information with official sources. This dynamic suggests that the journalist conveys a single version of the facts as if they were the truth, confident that the institutions are telling them the facts or the gist. The reality is that the media and journalists have made countless mistakes by following the discourse of official sources almost mindlessly. There are also the interests of parties holding government positions or incriminating police reports in which the version of the detainee or accused never surfaces.

Despite the above, the interviews demonstrate, especially in the case of Spain, a willingness on the part of journalists to learn from past mistakes and adapt to the current situation of limited time and resources. To this end, some choose to give up the race for immediacy and invest in slower journalism, which focuses on specific themes and is rigorously prepared. The media outlets featuring this type of journalism thus have a chance of standing out from those that go for the “tyranny of clicks”.

Based on the information, it is possible to conclude that the journalists interviewed strive for an improvement in the quality of their information, as they are aware of their excessive dependence on institutional sources, the existence of prejudices and political interests among the local ruling class and their limited ability to correctly verify disinformation/misinformation content, due to the scarcity of models, the lack of training in technological tools and the immediacy imposed by digital content. Journalists are aware of the problem and how the decline in the quality of information undermines public confidence, and they are the first to take an interest in tackling these problems, learning from their experiences and implementing new approaches in their newsrooms.

Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of this study, which, as stated, is exploratory. The number of interviews may be considered small and based on two countries. However, they allow for the collection of indicators on a little-studied area: disinformation/misinformation on a local scale (Jerónimo & Esparza, 2022) and, above all, fact-checking practices and challenges for journalists working in the local media. Thus, quantitative studies, such as surveys of journalists and media in other countries, could be promoted. The same goes for the prospect of collaboration by the public in the verification process (Allen et al., 2021), but studying this possibility with and around local media.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of an ongoing project (PTDC/COM-JOR/3866/2020) funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal.

REFERENCES

Abernathy, P. M. (2018). The expanding news desert. Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media. [ Links ]

Abernathy, P. M. (2020). News deserts and ghost newspaper: Will local news survive? Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media. https://www.usnewsdeserts.com/reports/news-deserts-and-ghost-newspapers-will-local-news-survive/ [ Links ]

Alcaide-Pulido, P. (2023). La lucha contra la desinformación en los contextos locales. Revista Multidisciplinar, 5(2), 157-175. https://doi.org/10.23882/rmd.23145 [ Links ]

Allen, J., Arechar, A. A., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Scaling up fact-checking using the wisdom of crowds. Science Advances, 7(36), Artigo eabf4393. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abf4393 [ Links ]

Amaral, I., Simões, R. B., Jerónimo, P., & Fidalgo, M. (2020). Facebook y periodismo de proximidad: Estudio de caso de los incendios en Portugal de 2017. In A. M. V. Dominguez (Ed.), Aproximación periodística y educomunicativa al fenómeno de las redes sociales (pp. 181-193). McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Ardia, D., Ringel, E., Ekstrand, V. S., & Fox, A. (2020). Addressing the decline of local news, rise of platforms, and spread of mis-and disinformation online. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [ Links ]

Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación. (2018). Marco general de los medios en España 2018. https://www.aimc.es/otros-estudios-trabajos/marco-general/descarga-marco-general/ [ Links ]

Bell, E., Owen, T., Brown, P., Hauka, C., & Rashidian, N. (2017). La prensa de las plataformas. Cómo Silicon Valley reestructuró el periodismo. Columbia University. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8B86MN4 [ Links ]

Camponez, C. (2002). Jornalismo de proximidade - Rituais de comunicação na imprensa regional. Minerva. [ Links ]

Couraceiro, P., Paisana, M., Vasconcelos, A., Baldi, V., Cardoso, G., Crespo, M., Foá, C., Margato, D., CanoOrón, L., Cabrera García-Ochoa, Y., Crespo, A., López-García, G., Llorca-Abad, G., Moreno-Castro, C., Rubio-Candel, S., Serra-Perales, A., Valera-Ordaz, L., Vengut-Climent, E., Von Polheim-Franco, P., … Hernández Escayola, P. (2022). The impact of disinformation on the media industry in Spain and Portugal. IBERIFIER. https://doi.org/10.15581/026.001 [ Links ]

Edmonds, R. (2022, 29 de junho). An updated survey of US newspapers finds 360 more have closed since 2019. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/business-work/2022/an-updated-survey-of-us-newspapers-finds-360-more-have-closed-since-2019/ [ Links ]

Fernandes, J. C., Del Vecchio-Lima, M. R., Nunes, A. F., & Sabatke, T. S. (2021, 28 de agosto). Jornalismo para investigar a desinformação em instância local [Apresentação de comunicação]. VIII Seminário de Pesquisa em Jornalismo Investigativo, Online. [ Links ]

Galletero-Campos, B. (2018). Del periódico impreso al diario digital: Estudio de una transición en Castilla-La Mancha [Tese de doutoramento, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha]. [ Links ]

Galletero-Campos, B., & Jerónimo, P. (2018). La transición digital de la prensa de proximidad: Estudio comparado de los diarios de España y Portugal. Estudos em Comunicação, 1(28), 55-79. https://doi.org/10.25768/fal.ec.n28.a03 [ Links ]

García-de-Torres, E., Yezers’Ka, L., Rost., A., Calderín, M., Edo, C., Rojano, M., Said-Hung, E., Jerónimo, P., Arcila-Calderón, C., Serrano-Tellería, A., Sánchez-Badillo, J., & Corredoira, L. (2011). Uso de Twitter y Facebook por los medios iberoamericanos. EPI - Revista internacional de Información, Documentación, Biblioteconomía y Comunicación, 20(6), 611-620. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2011.nov.02 [ Links ]

Graves, L. (2016). Deciding what’s true: The rise of political fact-checking in American journalism. Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Graves, L. (2018). Understanding the promise and limits of automated fact-checking [Fact sheet]. Reuters Institute; University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-02/graves_factsheet_180226%20FINAL.pdf [ Links ]

Izquierdo Labella, L. (2010). Manual de periodismo local. Editorial Fragua. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J., & Jerónimo, P. (2021). Changing the beat? Local online newsmaking in Finland, France, Germany, Portugal, and the U.K. Journalism Practice, 15(9), 1222-1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1913626 [ Links ]

Jerónimo, P. (2015). Ciberjornalismo de proximidade: Redações, jornalistas e notícias online. LabCom.IFP. [ Links ]

Jerónimo, P., & Esparza, M. S. (2022). Disinformation at a local level: An emerging discussion. Publications, 10(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications10020015 [ Links ]

Jerónimo, P., Ramos, G., & Torre, L. (2022). News deserts Europe 2022: Portugal report. LabCom; MediaTrust.Lab. https://doi.org/10.25768/654-875-9 [ Links ]

Lusa. (2022, 4 de junho). Portugal tem 61 concelhos sem jornais e rádios com sede: “Deserto de notícias vai agravar-se”. Jornal de Negócios. https://www.jornaldenegocios.pt/empresas/media/detalhe/portugal-tem-61-concelhos-sem-jornais-e-radios-com-sede-deserto-de-noticias-vai-agravar-se [ Links ]

Lyons, T. (2018, 23 de maio). Hard questions: What’s Facebook’s strategy for stopping false news? Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2018/05/hard-questions-false-news/ [ Links ]

Meta. (s.d.). Programa Acelerador do Meta Journalism Project. Retirado a 29 de junho de 2022 de https://www.facebook.com/formedia/mjp/programs/global-accelerator [ Links ]

Morais, R., & Jerónimo, P. (2023). “Platformization of News”, authorship, and unverified content: Perceptions around local media. Social Sciences, 12(4), Artigo 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040200 [ Links ]

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Eddy, K., & Nielsen, R. (2022). Reuters institute digital news report 2022 (Vol. 2022). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/Digital_News-Report_2022.pdf [ Links ]

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Shulz, A., Andi, S., Roberston, C., & Nielsen, R. (2021). Reuters institute digital news report 2021 (Vol. 2021). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-06/Digital_News_Report_2021_FINAL.pdf [ Links ]

Nielsen, R. (2015, 17 de junho). More and more media, less and less local journalism. European Journalism Observatory. https://en.ejo.ch/digital-news/more-and-more-media-lessand-less-local-journalism [ Links ]

Park, J. (2021). Local media survival guide 2022: How journalism is innovating to find sustainable ways to serve local communities around the world and fight against misinformation. International Press Institute. https://ipi.media/local-journalism-report-survival-strategies [ Links ]

Radcliffe, D. (2018, 27 de novembro). How local journalism can upend the ‘fake news’ narrative. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-local-journalism-can-upend-the-fake-news-narrative-104630 [ Links ]

Ramos, G. (2021). Deserto de notícias: Panorama da crise do jornalismo regional em Portugal. Estudos de Jornalismo, (13), 30-51. [ Links ]

Rivas-de-Roca, R. (2022). Calidad y modelos de negocio en los medios de proximidad. Estudio de casos en Alemania, España y Portugal. Estudos em Comunicação, 34, 81-96. https://hdl.handle.net/11441/133912 [ Links ]

Said-Hung, E., Merino-Arribas, M., & Martínez-Torres, J. (2021). Evolución del debate académico en la Web of Science y Scopus sobre unfaking news (2014-2019). Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico, 27(3), 961- 971. https://doi.org/10.5209/esmp.71031 [ Links ]

Said-Hung, E., Serrano-Tellería, A., García-De-Torres, E., Calderín, M., Rost, A., Arcila-Calderón, C., Yezers’ka, L., Bólos, C. E., Rojano, M., Jerónimo, P., & Sánchez-Badillo, J. (2014). Ibero-American online news managers’ goals and handicaps in managing social media. Television & New Media, 15(6), 577-589. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476412474352 [ Links ]

Satariano, A., & Isaac, M. (2021, 3 de setembro). El socio silencioso que hace la limpieza de Facebook por 500 millones al año. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/es/2021/09/03/espanol/facebookmoderacion-accenture.html [ Links ]

Sharma, P. (2021). Coronavirus news, markets and AI: The COVID-19 diaries. Routledge. [ Links ]

Torre, L., & Jerónimo, P. (2023). Esfera pública e desinformação em contexto local. Texto Livre, 16, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-3652.2023.41881 [ Links ]

Wiltshire, V. (2019). Keeping it local: Can collaborations help save local public interest journalism? Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [ Links ]

1Other concepts are acknowledged, such as “local journalism” or “regional journalism”. Although the original Portuguese version of this study used the term “proximity journalism” because it is the most widespread in countries such as Portugal, Spain or Brazil. This English version uses the term “local journalism”, because it is the most widespread concept within the scientific community that communicates in English. For the same reason, we will consider “local media” in this English version.

2Facebook third-party fact-checking programme (Lyons, 2018).

3Guide to the Facebook Accelerator programme (Meta, n.d.).

Received: February 03, 2023; Accepted: July 11, 2023

texto en

texto en