Introduction

Some political events in recent years have stimulated the news media’s interest in the new communicational conjuncture of populist phenomena. Whether referring to the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States, or the election of Jair Bolsonaro to the Presidency of Brazil (Araújo & Prior, 2020; Wells et al., 2020); whether in relation to Brexit or to the emergence and strengthening of parties and movements deemed as populists in Finland, Netherland, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, among other countries (Aalberg et al., 2017; Hughes, 2019; Lochocki, 2018; Moffitt, 2016; Ostiguy et al., 2021; Reinemann et al., 2019;), the media uses the term “populism” as a concept that aggregates elements that define a way of acting and communicating politically (Hafez, 2017). This use, notably elastic, does not seem to contribute to the clarity of the phenomenon in the public sphere (Akkerman, 2011; Bale et al., 2011; Herkman, 2016; Ward, 2019).

In addition to this inconsistency observed in the news media, “populism” is commonly highlighted due to the lack of clarity in the academic environment, where it has been the subject of profound debates (Cannon, 2018; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, 2017; De Cleen et al., 2018; Krämer, 2018). Nevertheless, this conceptual problem seems to acquire a new significance in light of the current international political context and of a growing media attention towards the phenomenon, where the use of the term “populism” goes beyond the academic domain to occupy a relevant place in the public sphere.

Faced with this problem, three possible perspectives for observing populism stand out: one that considers it an ideology (McRae, 1969; Mudde, 2004; Wiles, 1969); one that examines it as a discourse (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, 2017; De Cleen et al, 2018; Hafez, 2017; Laclau, 2005); and one that defines it as a style (Krämer, 2018; Moffitt, 2016;). Regardless of whether it is defined as an ideology, a discourse or a style, there is an agreement that populism underlies a logic of antagonism, in which the leader calls himself the role of representative of the “people” as opposed to the “elites” who, in a discursive construction, are blamed for social decay (Laclau, 2005; Moffitt, 2016).

Building on the threats that rhetoric and political phenomena aligned with populism may pose to democratic regimes and to the democratic role of the press, scholarship on political communication and populism has shown particular interest in the link between populist phenomena and journalism (Otto & Köhler, 2018; Ward, 2019). Within this field of research, different approaches have emerged focusing on the role of the news media in the emergence of the populist phenomenon, in the representation of populist actors and organizations in the press, or in the connection between news consumption patterns and populist attitudes (Bale et al., 2011; Reinemann et al., 2019; Tumber & Waisbord, 2021; Wettstein et al., 2018). In this context, this systematic review comprises studies that comprehend an empirical examination of the interaction between populism and news media.

This paper begins by presenting the research questions that structure this work, as well as describing in detail the procedures of selection, screening, and analysis of the qualitative synthesis. The results section is divided into four segments, which aim to briefly describe the studies that were not included, to present the main characteristics of the examined studies, to identify the issues and realities that are the focus of the analyses, and to describe the main methodological approaches employed in these studies. Along with a proposal for typifying conceptual approaches to studies on populism and news media, this paper identifies some noticeable features that suggest trends, gaps, and possibilities for future research.

Research questions and methodology

Arising from a more circumscribed research work focused on characterizing the representation of populism in news media, this initial exploratory study aims to map and describe different trends of research concerned with the relation between the phenomenon of populism and news media. Specifically, this analysis seeks to address the following research questions:

RQ1 What are the research subjects and issues addressed by empirical studies that focus on populism and news media?

RQ2 - What are the research practices adopted by these studies to address populism and news media?

Systematic Literature Review (SLR) consists of a methodology oriented to locate, select, systematize, and synthesize existing studies and evidence on a specific research topic. It comprehends a detailed description of the procedures for collecting and analyzing the literature, allowing for a reduction of bias and greater transparency. In this sense, SLR may also offer important contributions not only to account for existing research, but also to identify emerging tendencies and opportunities for forthcoming research (Bhimani et al., 2019; Dacombe, 2018; Denyer & Tranfield, 2009; Pickering & Byrne, 2014).

In different subdomains of Communication Sciences, several studies have adopted SLR to characterize the situation of the scholarship on a particular subject or to systematize and evaluate evidence on a specific issue (just as an example: Engelke, 2019; MacDonald et al., 2016; O’Brien et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). This analysis comprehends methodological contributions from these different studies, as well it seeks to incorporate PRISMA’s guidelines applicable to this specific SLR (PRISMA, n.d.).

This study comprised two fundamental stages. The first phase comprehended the identification, screening and eligibility of studies included in the qualitative synthesis. Building on information provided by electronic databases and based on a content analysis approach, the second phase encompassed the identification and characterization of the main elements of the studies that allow us to address the research questions.

2.1 . Search process

The search for studies included in this analysis was conducted in two electronic databases: Scopus and Web of Science (WoS), in July 2021. We performed a search for a specific query string in TITLE, ABSTRACT, and KEYWORDS of articles published in journals. Different configurations of the query string were tested to achieve a comprehensive representation of the records included in the qualitative synthesis. In this context, the following more wide-ranging search string was applied:

(populis*)

AND

(journalis* OR news OR media)

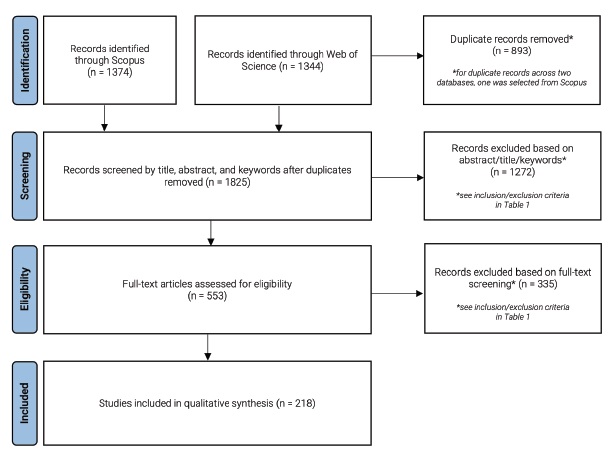

This process yielded 1374 records from Scopus database and 1344 records from Web of Science database (Figure 1). From these records, 893 duplicates were identified and removed.

2.2. Screening and eligibility

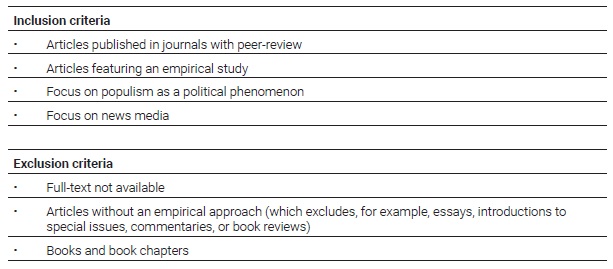

The 1825 records arising from the duplicates’ elimination process were screened based on title, abstract and keywords. Screening was grounded on the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Table 1 and was performed separately and redundantly by two researchers. Discrepancies were, subsequently, re-analyzed, discussed, and resolved.

Also established on the outlined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a second round of screening involved the assessment of full texts for eligibility. Again, this process was individually and redundantly performed by two researchers. A total of 335 records were excluded based on this full-text screening.

2.3 Analysis

With the aim of characterizing the 218 studies included in the qualitative synthesis and identifying the fundamental elements that allow us to address the research questions, a database with two types of variables was built.

A first set of variables derives from the information provided by electronic databases regarding the records included in the sample. Among these data, the following were used in this study: (a) year of publication; (b) authors; (c) authors keywords; (d) journal. For the second set of variables, a content analysis approach (Krippendorff, 2018) was applied with the purpose of identifying characteristics of the studies that were not covered by data retrieved from the databases. From a more deductive procedure, (e) the research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed approach), (f) the methodological options and (g) the regional focus of the studies (by country and by continent) were analyzed. On a more inductive approach, this analysis sought to identify and systematize (h) the phenomena and (i) major conceptual dimensions of populism and news media addressed in the studies. Once again, this process was carried out independently by two researchers, and the divergences were later discussed and resolved.

Statistical descriptive analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 26.

3. Results

In addition to exclusions due to duplication of records, the description of the screening and eligibility processes suggests a substantial contraction of the corpus of analysis. This observation highlights the relevance of proceeding with a concise characterization of the excluded studies.

Along with records deleted due to more procedural factors, such as not corresponding to peer-reviewed articles or not providing the full text, another important explanation pertains to the extensive number of articles that do not focus on the link between news media and populism as a political phenomenon.

A broad segment of previous research has emphasized the link between populism and social media, exploring how political actors use these new channels of direct communication, the impact of the use of these media on the formation of populist attitudes, or the role of these platforms in the emergence of new populist movements (Gerbaudo, 2018; Salgado, 2019). While these analyzes are important to understand the transformations in political communication and constitute a significant amount of the excluded studies, they transcend the specific object of this research.

On the other hand, the literature tends to emphasize the heterogeneity and conceptual dispute around the term populism, whose use often goes beyond its political or ideological meaning (Galito, 2018; Krämer, 2014; 2018). In this regard, although less frequent, studies were excluded due to a contrasting use of the term “populism”, other than its political meaning.

3.1 Characterization of studies on populism and news media

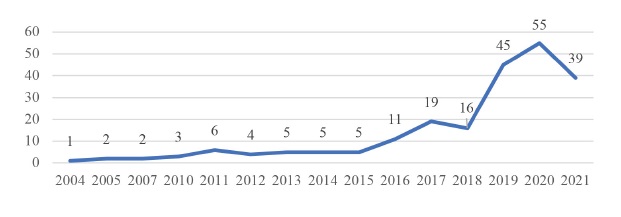

As identified in Figure 2, it is mainly from the mid-2010s onwards that studies focusing on the relationship between news media and populism emerged. Despite a slight drop in 2018, the number of publications has significantly increased since 2016: 85,1% of publications stem from the 2016-2021 period.

Figure 2 Frequency of published studies on populism and news media per year. Note: n=218. Source: authors

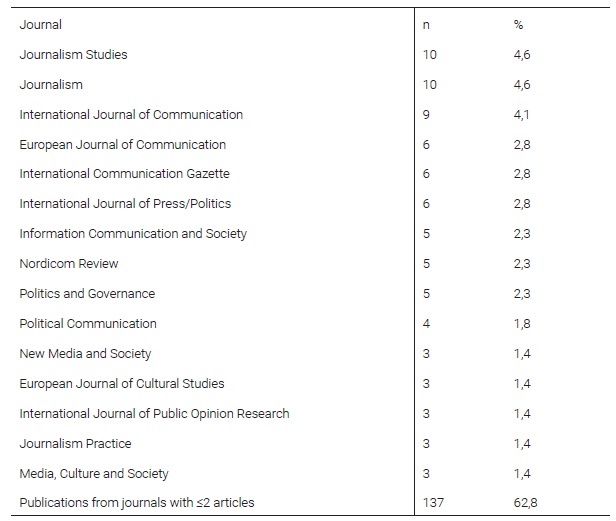

The articles that make up the sample of this analysis were published in 132 different journals. This corresponds to an average of 1.7 articles per journal. This diversity of publications is also evidenced by the fact that the set of records published in journals that contain ≥3 articles correspond to 37,2% of the total of studies (Table 2). Of these 132 journals, 120 are in the Social Sciences domain.

Based on SCImago Journal Rank’s (2021) subject areas and categories for each journal, this analysis aimed to map the disciplines in which the different records are located. Following what has already been observed, the large majority of articles (201) is in the field of Social Sciences. In parallel, 48 records are found in the domain of Arts and Humanities and 10 records in the field of Computer Science. Other more underrepresented subject areas include, for example, Psychology (3), Economics, Econometrics and Finance (3), or Business, Management and Accounting (3).

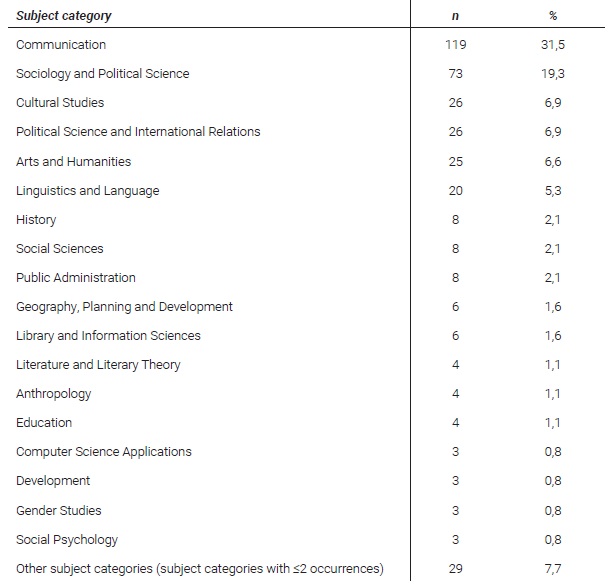

Also, in line with what has been previously detected, it is evident that it is mainly the areas related to Communication Sciences and Political Sciences that constitute the most represented scientific domains in this sample (Table 3). This aspect obviously cannot be dissociated from the objectives and strategies that underpinned the selection of studies included in the qualitative synthesis.

Table 3 Most frequent categories of journals that include studies on populism and news media

Note: n=378. Subject areas and categories were determined using SCImago Journal Rank (2021) information. Coding of multiple categories per journal was possible. It was not possible to determine subject areas and categories of 8 journals (n of articles=9). Source: authors

3.2 Research issues on populism and news media

In view of the premises underlying RQ1, this analysis paid particular attention to the issues and research objects that shape the examined studies.

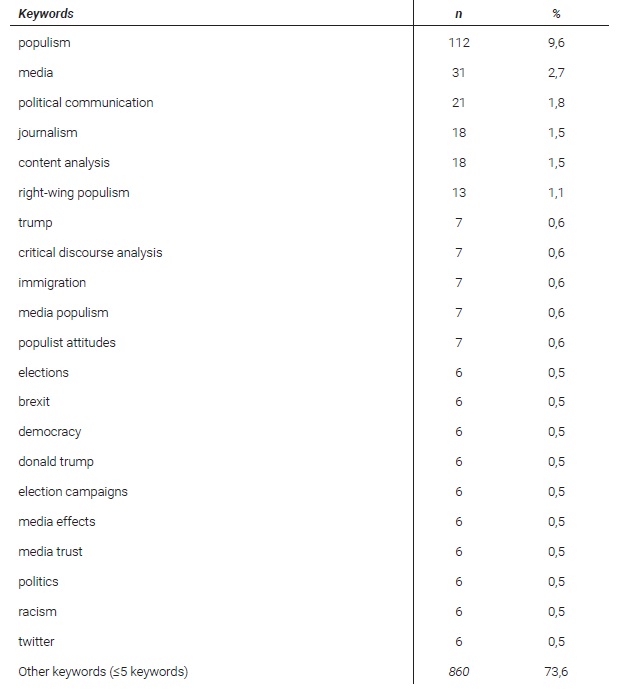

Again, considering the objectives and methodological strategies of this study, the overrepresentation of author keywords related to populism and the fields of media and political communication (Table 4) is not unexpected. In fact, 87,6% of articles with author keywords contain a term derived from populism in their title or keywords, and 95,5% contain a reference to communication, news, journalism, media, or specific types of media.

While the diversity of keywords suggests heterogeneity in the subjects and approaches of the different studies, a broader reading of the terms allows the identification of trends related to the addressed problems and phenomena. An example of this last element is the substantial set of references to political actors, political movements, or specific media outlets.

Table 4 Most frequent author keywords in studies on populism and news media

Note: n=1168. It was not possible to determine author keywords of 16 articles. Source: authors

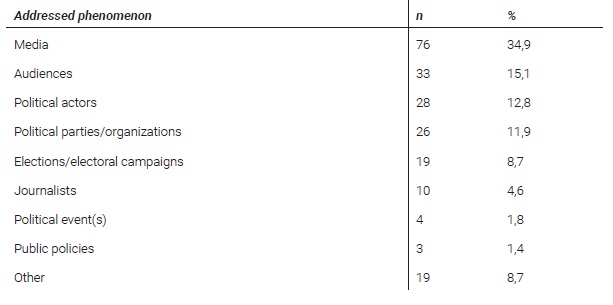

As the data indicated in Table 5 point out, a substantial number of studies particularly focus on the media. This comprises a relatively wide range of issues, such as the performance, characteristics, or narratives of populist and hyper-partisan media; how the news media frame and interact with political actors or organizations; or the role of media in stimulating or challenging populist policies or populist agents.

Concurrently, the emphasis on audiences encompasses issues such as news consumption, trust in news media or media effects. The focus on political actors or organizations is largely associated with the way these elements are represented in and by the media, or the way they express and communicate through news media.

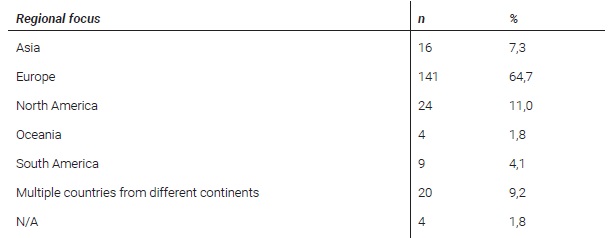

Regarding the contexts prioritized by research on populism and news media, the data presented in Table 6 suggest a predominance of studies focused on the Americas and, mainly, on Europe. Considering the specific national dimension, it is the United States that emerges as the most represented country: 23 studies focus exclusively on the USA context. The other most featured national realities include the United Kingdom (19 studies), Netherlands (17), Germany (9), Finland (7), and Sweden (6).

Thirty-eight studies address different sets of European countries - in a total of 23 singular countries, Germany (13), Sweden (13), France (10) and the United Kingdom are the ones that most frequently integrate these analyses. On the other hand, 20 studies comprehend comparative or integrated analyzes of countries from different continents (Table 6). Among the 16 singular countries included in these sets, it is again the USA (15), UK (8) and Netherlands (6) that are more frequently found.

It is worth noting that none of the examined studies focus specifically on African contexts.

As noted above, the literature on populism and communication points towards a relatively broad spectrum of different issues, problems and subjects that may constitute the focus of these studies (Aalberg et al., 2017; Hughes, 2019; Lochocki, 2018; Moffitt, 2016; Ostiguy et al., 2021; Reinemann et al., 2019).

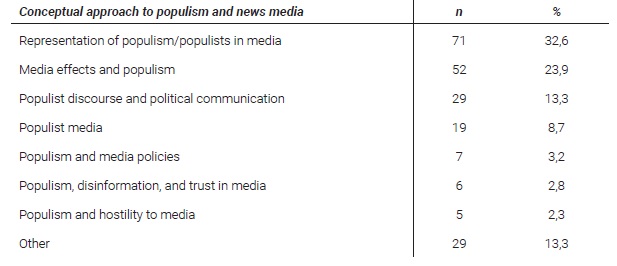

Along with the identification of the analyzed phenomena, we aimed to identify the major conceptual dimensions, or conceptual approaches, referring to the relationship between populism and news media. Based on contributions from literature and a deductive analysis of how the relation between news media and populism is studied, we have identified and constructed seven major classification categories for the conceptual approach to this problem (Table 7):

Representation of populism/populists in media: The most representative category refers to the analysis of how news media depict populism as a concept or as a political phenomenon, but also how the news media portray populist actors, organizations, and policies. Examples of this category can be found in Herkman’s (2016) analysis on the meanings given to the term populism in the Nordic press, in the study of Bos et al. (2010) on the media coverage of right-wing populist leaders, or in Snipes and Mudde’s (2020) work about media framing of Marine Le Pen.

Media effects and populism: A second dimension comprises the effects of news media action or populist communication through news media, as well as news exposure or media attention in promoting specific attitudes, emotions, or perceptions in audiences. This includes, for example, the exploratory study by Cremonesi et al. (2019) on how the exposure to political information through media outlets is associated with populist attitudes, the Murphy and Devine (2020) study on the relation between British UKIP news coverage and the level of public support for the party, or the Ramírez-Dueñas and Vinuesa-Tejero (2021) study on the effects of selective exposure on partisan polarization.

Populist discourse and political communication: A third variety of studies is related to the ways populist discourse and communication of parties, movements and political actors pervades and/or affects media political coverage or discourse. Examples of this range can be seen in Smith et al.’s (2021) article about the United Kingdom press during Brexit referendum or in the study of Esser et al. (2019) on favorable opportunity structures for populist communication.

Populist media: A fourth category focuses on populist or hyper-partisan news media activity, rhetoric, agenda, or content. Such articles include, for example, the study by Bhat and Chadha (2020) on ‘OpIndia.com’ or the study by Falcous et al. (2019) on ‘Breitbart Sports’.

Populism and media policies: A fifth strand of research encompasses the association between populist political conduct, populist actors or populist institutions of power, and media policies. Examples of this set of studies are the contributions by Tapsell (2021) on the challenges facing Philippines’ media during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, by Kenny (2020) on the association between populist rule and a decline of press freedom, or by Pons and Hallin (2021) on media reform and press freedom in Ecuador.

Populism and hostility to the media: The category of hostility to the media includes not only studies on attacks on news media, such as the study of Solis and Sagarzazu (2019) on Hugo Chávez’s verbal attacks against independent media in Venezuela, but also research on the strategies of journalists and media to challenge these attacks, such as the Panievsky (2021) study on how Israeli journalists respond to antimedia populist hostility.

Populism, disinformation, and trust in media: The last category addresses the analysis of the association between misinformation, trust in the news and populist attitudes, such as the study by Arlt (2019) on the factors that shape trust in the news media, or the study by Fawzi and Mothes (2020) on the relation between the expectations and evaluations of the audiences, the trust in the media, and socio-political predispositions or individual media use.

3.3 Research practices on populism and news media

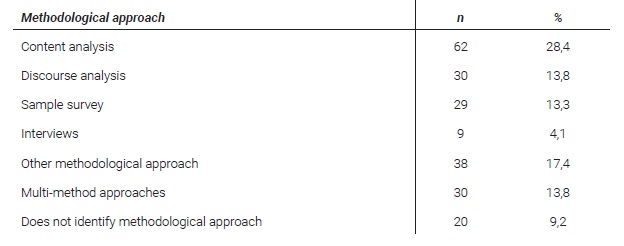

Regarding the research design, more than half of the studies (51,8%) adopt a more qualitative approach, while 38,1% follow a quantitative strategy, and 10,1% apply mixed-methods procedures. On the other hand, most studies that identify the methodological approach implement a single-method strategy (84,8%), while 15,2% are multi-method.

As the data in Table 8 displays, content analysis is the single method most used in the studies, followed by discourse analysis, sample surveys and interviews. Other less frequent methodological approaches include, for instance, framing analysis, different modalities of textual analysis or network analysis.

4. Discussion

This paper sought to systematize and chart scholarship on populism and news media. In this context, we aimed to identify features of these studies, but also to characterize the subjects, conceptual approaches, and methodological angles. Considering the main findings, a set of trends and results can be highlighted and deserve further reflection and discussion.

4.1 Populism and news media as a growing field of research

A first trend worthy of being emphasized concerns not only the continuous and progressive growth of research outputs on populism and news media, but also, and especially, a striking increase of this domain since the last six years: this period comprises 85.1% of all records included in the sample of this study.

Notwithstanding more specific explanatory factors that will be further addressed, this development of the research focus on issues of populism and news media must be observed in the context of a growing interest in the field of Political Communication and, more specifically, in the issues of Populism (Ostiguy et al., 2021; Reinemann et al., 2019). In fact, if we extend the analysis to the evolution of the total set of records retrieved from Scopus and Web of Science - before the selection and screening processes -, we may recognize a similar growth trend: 76,9% of records were published in 2015 or after, and 60% were published on the year 2018 or after. Regarding the sample of this study, it is also worth noting that during the current year of 2021, until July (end of the survey period), 39 studies were published, suggesting a potential to again exceed the number of publications registered in the previous year.

While the lack of quantitative evidence does not allow us to draw definitive or categorical conclusions, we hypothesize that this evolution in research interest in populism and news media may also arise from a growing public and journalistic interest in populism issues, linked to an increasing media attention not only to a more conceptual dimension of the populist phenomenon, but also to the emergence of new political organizations and actors in different geographic realities. Moreover, it is suggested that this hypothesis may meet previous analysis findings (for example, but not exclusively, Brookes, 2018; Brown & Mondon, 2020; Doroshenko, 2018; Krämer & Langmann, 2020; Wettstein et al., 2018) in highlighting leads for future transnational and comparative studies on the evolution of media attention to populist phenomenon(s).

On a more methodological note, this observed growth of studies cannot be dissociated from an expansion and progressive inclusion of new journals in the two databases employed in this analysis.

4.2 Populism and news media as a research field rooted in the Social Sciences

Despite the wide diversity of journals publishing research on populism and news media (the qualitative synthesis presents an average of 1.7 articles per journal), this survey suggests a narrowing of these studies in the field of Social Sciences (90.9% of the 132 journals are found in this scientific area), as well as in the disciplines of Communication and Political Sciences: 39.4% of journals assume “Communication” as a subject category and 46.2% have “Sociology and Political Science” or “Political Science and International Relations” as subject categories. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that only 9.2% of all articles are published in journals that combine a focus on both Communication and Political Sciences, suggesting that research on populism and news media does not result from an interdisciplinary combination of these two fields. Even though research on these issues is deeply established in the field of Social Sciences, less than half of the articles (41.3%) are published in journals limited to just one subject area and one subject category, implying some level of transor interdisciplinarity of this field of research. In addition, the genesis of most of these studies within the scope of Social Sciences, and Communication and Political Sciences, may provide an explanation for the predominance of empirical approaches linked to consolidated methodological options in these areas, such as content analysis, discourse

analysis or sample surveys.

4.3 Populism and news media as a multidimensional research object

If the survey of disciplines that harbour these studies alludes to a narrowing of scientific domains, the analysis of the covered subjects and issues points towards a disparity or heterogeneity of research interests. This outcome is particularly evident regarding the phenomena or the objects that are the focus of the analysis, where, despite a predominance of studies concerned with the role of the media, it is possible to observe an unfolding of different subjects of research, which correspond to different locations of the interaction between populism and the news media, such as political actors and organizations, events, journalists, or audiences. It is proposed that, in a future study, these elements may be the object of a more in-depth characterization with a view to identifying specific characteristics.

On the other hand, the typification of conceptual angles that we propose in this study reveals a heterogeneity of analytical perspectives on the interaction between populism and news media. While approaches to the representation of populism and populists in the media emerge as one of the most representative dimensions in terms of breadth and temporal extension, there is evidence of the emergence of new perspectives concerned with distinct features of this interaction, such as the effects of the media and populism, the role of the media as agents of populism, or the impact of the intervention of populist actors and organizations on the social role of news media. We argue that this diversification of scopes reflects not only an unfolding of the research interest in populism and news media but may also express a complexification or densification of the phenomenon itself (Reinemann et al., 2019; Tumber & Waisbord, 2021). Ultimately, the research potential that resides in some of the less explored dimensions cannot be overlooked.

4.4 Populism and news media as a research field concentrated in specific regions

One of the most striking features of this characterization of research on populism and news media refers to a marked imbalance in the geographical realities addressed by the studies and a concentration of this field of research in elite nations. At the same time, there is a convergence of a considerable number of studies in a small group of countries: for example, six countries (USA, UK, Netherlands, Germany, Finland, and Sweden) are the focus of 52.6% of all records that address the specific reality of one nation. On the opposite side, the complete lack of studies focusing on the African context must be stressed. Different hypotheses may compete to explain this concentration of the research attention on these specific realities.

One possible explanation is that the focus of the research in these geographical contexts is the result of greater media attention to the emergence of new actors and new political movements in these countries. Although the lack of more in-depth quantitative and qualitative data does not allow us to draw definitive conclusions, we hypothesize that this focus on specific geographic contexts is intrinsically associated with the origins and realities of researchers practicing this field of studies. In fact, when we compare the regional focus of studies that address only one country and the affiliation of the authors of those analyses, in most cases (75.3%) the affiliation of at least one of the researchers corresponds to the country under study.

These specific results cannot also be dissociated from the languages and countries of the journals that publish the analysed studies; a context dominated by an Anglo-American paradigm. Relating to this, Scopus and Web of Science are databases in which journals based in Europe and in the United States are prominent, a fact that has implications for the national origin of publications and, therefore, may explain the thematic interest in some national realities at the expense of others. In a different perspective, the quantity of studies addressing different countries (27.5% of the records focus on a combination of different geographic contexts) is representative of the comparative and cross-national interest of this field of research.

Although strategies have been employed to overcome some of the weaknesses that may arise in this sort of systematic reviews (such as a detailed description of methodological procedures or the triangulation and redundancy of researchers in data collection and analysis), the findings of this study come with a set of relevant limitations. First, the analysis focuses on articles published in peer-reviewed journals, which may have excluded other empirical approaches published in monographs, book chapters or conference proceedings. Moreover, data collection was limited to Scopus and Web of Science databases, dismissing studies published in non-indexed journals. While the query string used in this analysis results from different pre-tests aimed at achieving a comprehensive representation of the research included in the qualitative synthesis, we admit the existence of studies on populism and news media whose title, abstract or keywords do not correspond to the terms applied in this search. Finally, this qualitative synthesis is ultimately reliant on the authors’ interpretation of the different concepts and paradigms surrounding these studies. This possible bias is particularly relevant regarding the more inductive procedure of identifying and classifying features with more blurred boundaries, such as the phenomena analysed and the conceptual approaches of populism and the news media. This systematic literature review aimed to chart, analyse, and synthesise the scholarship on populism and news media. In doing so, this paper sought to systematize the main conceptual and methodological strategies applied in empirical approaches to this research subject. With this systematic review, we expect to contribute to a deeper understanding about this research field, while also seeking to outline and to provide leads for future studies. In this way, it is hoped that this analysis, while exploratory, may collaborate to a wider reflection and debate on a matter with remarkable social and political implications.