Introduction

In 2018, after 15 years of campaigning for the presidency, Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected President of Mexico in a landslide victory. The party he founded, Morena, also won absolute majorities in both chambers of the Mexican Congress, earning him an amount of political power unprecedented in the country’s recent history.

Following contested losses in 2006 and 2012, López Obrador left the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), then the largest left-leaning party in the country, to found Morena (Navarro, 2012). The party identifies itself as a democratic left-wing party, although it has often received criticism to the effect that it is ideologically centered around the figure of López Obrador as a leader, rather than any clear political ideal (Centeno, 2021). Ever since his tenure as Mexico City’s Head of Government in 2000 made him a central figure in the nation’s public eye, López Obrador’s discourse has increasingly incorporated an openly populist rhetoric, with a marked disdain for democratic and government institutions (Bruhn, 2012; Eisenstadt and Poiré, 2006; Schedler, 2007). This anti-institutional discourse did not change even after he assumed the presidency and his appointees became the officials in charge of said institutions. In the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak, trust and communication between the population and government are more important than ever. In this situation, a leader whose discourse has historically incorporated distrust of the government is potentially very problematic for the country’s handling of the pandemic, especially given that he wields unprecedented power and has made a point of gutting the technocratic sector’s independent capabilities (Ward, 2020).

Literature and Background

Although the concept of populism is frequently used both in academic and political discourse, there is only a semblance of consensus regarding its definition and characteristics. Over time, several different approaches to defining the term have emerged. While the origin of the term is contested, the proliferation of so-

-called populist Latin American regimes in the 20th century brought about a whole school of study on populism, first from a developmental macroeconomic approach (Cardoso and Faletto, 1979; Dornbusch and Edwards, 1989), then as a political strategy in the quest for power (Roberts, 2006; Weyland, 2001), and lastly, as a discursive -or ideationalframework (Hawkins, 2009; Laclau, 2005). In our opinion, the focus on discourse differs from the others in that it conceives populism outside of the ideological sphere, as a discursive framework with a set of procedural characteristics. Particularly, we subscribe to Paris Aslanidis’ response to Cas Mudde’s conception of populism as a thin-centered ideology: Aslanidis (2016) expands on Laclau’s work and frame theory to conceive populism exclusively as a discursive frame, dropping the ideological genus. While it is true that Mudde’s conception of populism has been greatly important to our understanding of the phenomenon -as Aslanidis himself proclaims-, we believe that a more pragmatic definition of populism as a procedural framework can be dramatically beneficial to empirical research on the subject, and can also help bridge the gap between qualitative and quantitative approaches to its study:

A research program that operationalizes populism as a discursive frame can encourage comparative work, facilitate cooperation with neighboring fields, shed light on borderline cases of populism and enable the construction of large datasets to systematically analyze the impact of populism as an independent variable. Besides, the majority of existing quantitative approaches to populism already implicitly analyze populism as a discursive phenomenon, remaining indifferent towards ideological or other implications, as explained previously (Aslanidis, 2016).

This is of particular interest to our methodological approach, which seeks to statistically analyze the influence of López Obrador’s discourse -as a discursive phenomenonon the communication of other government officials. This discursive-procedural approach, on the other hand, allows to conceive of populism as a phenomenon stemming from different ideological standpoints, rather than as a necessary consequence of ideology. That is not to say that there is no ideological charge to populism, but rather that there is not necessarily a single ideology that engenders populism: it is no coincidence that the rise of the discursive approach to populism coincides with the rise of European populism (Wodak et al., 2013), which -unlike Latin American populismis not accompanied by a left-wing ideology and anti-imperialism, but by right-wing sentiments, national exceptionalism, and xenophobia. The term “neo-populism” has been proposed to define the contemporary populist discourses in Latin America that incorporate right-wing ideas and implement free-market policies when in power (Waisbord 2003; Weyland, 2010), but this neologism perpetuates the notion that there is an essential difference between the original Latin American populism (often presented as virtuous or, at the least, born from righteous causes) and this new right-wing populism. If we understand populism not as a political stance or ideology but as a way of framing discourse in a binary of the wronged many against the wrongful few, this distinction is unnecessary. For these reasons, this study favors an understanding of populism as a type of political discourse. Along this line, Hawkins (2009) defines populism as “a Manichean discourse that identifies Good with a unified will of the people and Evil with a conspiring elite” (p. 4). We agree with this definition, which differs from Mudde’s in that it identifies it as a discursive procedure, rather than an ideology. If populism is a discursive framework then, the next step would be to figure out how to identify it or measure it in discourse. Here, many academics have emphasized the importance of analyzing discourse within its context and taking into account the entirety of its spatial/temporal/social/cultural situation. Some of these academics favor a thematic or holistic approach, in which the entirety of a communication is graded as a whole to identify underlying populist themes (Hawkins and Rovira 2018; Poblete 2015). There is another approach -that of content analysiswhich quantitatively analyzes the presence of certain words and phrases (Poblete, 2015; Roodujin and Pauwels, 2011). Although human-based thematic analysis is always better for accuracy and depth, its proponents concede that with a large enough volume of data, automated content analysis is a viable -if imperfectoption (Hawkins and Castanho, 2016). As the speed and volume of social media publications by government officials grows at break-neck speed throughout the world, these types of automated analyses increasingly become the norm. The works of Aslanidis (2018), Boberg et al. (2020), and Ernst et al. (2017) are some examples of this trend. Here we see again the importance of understanding populism as a discursive frame, which allows us to analyze its presence in text through large-scale quantitative projects:

Employing the populist frame as a coding unit in text analysis projects provides an improved analytical ground for empirical applications and enhances reliability and validity in measuring populism (Alsanidis, 2016).

As we’ve established, the discursive framework of populism is centered around the binary of the rightful many wronged by the evil elite. When populist factions are in power, it’s a common practice -though not ubiquitousto also frame policy-making in this Manichean discourse of “the people against the elite” to silence and limit the influence of opposing political actors. Populist leaders and regimes attack those institutions that, in their view, fail to produce the ‘correct’ outcomes according to their moral truth (Müller, 2017). Müller believes that this only happens when they are the opposition, but as we have seen in the past few years, anti-institutionalism doesn’t necessarily end after election day: the new wave of populist-

-leaning leaders often continue to speak against actors and agencies in their own administration, particularly those which favor empirical information over the moral truth of the movement. This particular brand of anti-institutionalism from power has been studied more in right-wing governments (McCool, 2019), but it can also be found in left-wing populist governments, particularly those with an anti-establishment mindset.

Anti-establishment populism, as categorized by Kyle and Gultchin (2018), presents the people as hard-working victims of a state run against their interests by corrupt political elites, who will be vanquished by a strong, pure leader. Unlike socio-economic populism, whose antagonist is international ‘Capital’ and cultural populism, which antagonizes minorities, anti-establishment populism has a clear and definite enemy: the political apparatus. When the populist faction assumes control of said apparatus, the narrative continues, now framed in the duality of the leader purging corruption from the inside (‘draining the swamp’).

Such is the case of Mexico’s president, who has vocally opposed government workers and institutions since day one of his administration, from the Supreme Court (Martin, 2018) to the lower bureaucracy (Dussauge-Laguna, 2021). López Obrador has risen to power on a platform of uniting the Mexican electorate against a perceived common enemy: the “deep state” or “power mafia” (Mafia del Poder), a supposed cabal of politicians and corporate overlords intent on destroying the country to further their own agendas and increase their wealth (Gutiérrez Martínez, 2020). López Obrador’s discourse -which transcended his campaign and is now a consistent part of the president’s daily morning conferencepresents him as a messiah who will oust this power mafia and enact the “Fourth Transformation” of Mexico’s history (the first three corresponding to culturally significant historical events), and draws a historical line from beloved historical figures to himself as the hero of this transformation (Sáez, 2019). López Obrador’s populist rhetoric has been studied from academia ever since his tenure as Head of Government of Mexico City (Bruhn, 2012; Eisenstadt and Poiré, 2006; Schedler, 2007), but it has garnered renewed interest since his election as President. Serrano defines López Obrador’s brand of populism as “moderate-left populism” (2019), while Rentería & Arellano-Gault (2021) propose the term “downsizing populism” to illustrate López Obrador’s conflation of all government workers, technocrats and bureaucracy into the figure of the enemy elites, which other proponents might argue fits into the definition of anti-establishment populism mentioned earlier.

Of course, the potential consequences of López Obrador’s populism for the country beyond the realm of words have been an object of concern and study in the past few years: Puente (2020) warns about the undermining of the legislative branch by his discourse, while Flores, Andrade, Ávalos & Torio (2021) conceptualize his populism as an intersection of communication, ideology, and strategy. Olvera (2021) ponders on his attacks on judicial institutions and the media, and analyzes the risk of an impending authoritarian turn in the regime. Most worries in the past year, however, have centered around the country’s response to the Covid-19 emergency. Rentería & Arellano-Gault found that the government’s actions during the pandemic have been based on an antagonism to science and expert knowledge, and an undermining of the technocratic and bureaucratic apparatus, including health institutions (2021). This finding is echoed by Manfredi, Amado-Suárez and Waisbord (2021), who studied his Twitter communication during the first months of the pandemic and found a marked lack of attention to health policy, when compared to other presidents in the region.

Indeed, from the onset of the Covid-19 global emergency, uneasiness was expressed both in Mexico and abroad over the president’s ability and disposition to handle the crisis (Flannery, 2020; Ward, 2020). This uneasiness was not unwarranted: from mass firings of doctors to fatal medicine shortages to massive cuts to the national health service (Ward 2020), López Obrador’s track record on the issue of health was controversial enough to merit valid concern.

Mexico’s Health Department deployed the first contingency measures a mere two days after the novel coronavirus was identified and unveiled a full response plan by January 30 (Secretaría de Salud, 2020). When the virus arrived in Mexico, though, the president made it clear that he didn’t believe the situation was dangerous: on February 28th, in the wake of the first cases detected in Mexico, he declared that Covid-19 was ‘not even close to the flu’ in terms of danger. On March 4, he urged the population to hug each other as a display of Covid-19 skepticism. On March 13th, he condemned ‘small’ politicians holding daily pressers on the state of the emergency and ‘spreading lies and misinformation’. On March 14th, he deliberately hugged and kissed people on his tour of the country, even as the Health Department unveiled a national campaign for social distancing and the Secretariat of Education announced the indefinite closing of schools. On March 16th, he scoffed at the idea of wearing a mask to his daily press conference. On March 19th, as the country entered Phase 2 of contagion, he declared that ‘honesty’ and ‘not allowing corruption’ were the shields that would protect the people from Coronavirus, and then produced a couple of religious images and a two-dollar bill from his wallet and credited them with protecting him from misfortune. On March 23rd, he urged the people to ‘not get spooked’ by the Health Department’s proposed safety measures and to ‘go out into the streets’. It wasn’t until March 27th, one month after the first confirmed cases in the country, that López Obrador finally addressed the population in a serious manner and urged them to remain at home, echoing the message that health officials had been repeating for weeks.

Historically, the ruling party in Mexico has demanded of the low-and-mid-level bureaucracy that they engage in active proselytism and repeat the leadership’s rhetoric (Magaloni, 2006; Tosoni, 2007). These same subsystems are mirrored in social media communication (Corona and Muñoz, 2018), with party lines dictating most of the individuals’ discourse. This organizational system now serves López Obrador, with the Fourth Transformation’s sword dangling above most officials’ heads: López Obrador has instigated a culture of fear among Mexico’s civil servants, constantly threatening mass layoffs and pay cuts (Agren, 2020) under the banner of his crusade to clear the corruption from the country’s government. Faced with this panorama, it’s not outlandish to hypothesize that the president’s vocal dismissal of the pandemic, evidenced both in this brief recount and in the findings of several studies (Manfredi, Amado-Suárez and Waisbord (2021; Rentería and ArellanoGault, 2021; Ríos, 2020), may have had a clear and direct impact on the way that the situation was handled at every level of government, regardless of the experts’ recommendations.

Approach.

The Covid Mexico Twitter Observatory is a research and monitoring project established at the start of the pandemic, to analyze the use of Twitter by state governments in Mexico during the Covid-19 emergency. It uses Python and the Twython library to collect tweets through Twitter’s API. The project collected all tweets posted by every government department relevant to the contingency during the first six months of the pandemic. For each state, we collected the tweets of the Governor’s Office as well as those of the Departments of Health, State, Public Safety, Education, Social Development and Tourism. When available, both the personal account of the appointed official and the institutional account were collected.

The observatory was established in early March, after the first cases of Covid-19 were confirmed in Mexico. As the situation developed and López Obrador voiced his own skepticism of the danger, it became apparent that the President’s attitude towards the emergency would have to be incorporated as a variable to observe. The president’s series of dismissive statements during the month of March contrasted the tangible actions of other people in his administration during the same time-period (particularly those of the Health Department and the ‘man-in-charge’ of Mexico’s pandemic response, Subsecretary of Prevention Hugo López-Gatell). This contrast led us to believe that the president’s messaging might become an important factor in the way officials communicated about the contingency on Twitter. When the first six months of data collection ended on July 7th, one of our first goals was to establish whether there was a relationship between the president’s discourse and the officials’ Twitter communication.

Data and Findings.

The dataset employed in this study comprises all tweets posted by pertinent state-level government departments during the first six months of the pandemic. Data collection began on January 7th -the day when Chinese authorities officially announced the existence of the new coronavirus (Li, 2020) and ended six months later, on July 7th. The observation list consisted of 327 Twitter accounts belonging to departments and officials from the 32 states, Mexico City and the federal government. This amounts to a total of 254,238 tweets. The dataset was indexed by date and time and grouped daily and weekly. The tweets were classified according to each state’s ruling party, assuming that all department heads share the governor’s party affiliation (a safe assumption, seeing as they are the highest ranks of state government and appointed directly and unilaterally by the sitting governor). The dataset was also classified by political affiliation according to the party in power in each state: Federally, Morena and Encuentro Social were classified as the ‘Ruling’ bloc with the rest of the parties constituting the opposition. Morena and Encuentro Social are politically divergent in paper (Encuentro Social is a Christian Conservative party). However, they formed a coalition for the 2018 election in which ES won the Governorship of Morelos, and Governor Cuauhtémoc Blanco is a self-professed supporter of López Obrador. Because of this, they are both classified under the ‘Ruling’ category.

This dataset -consisting of every tweet published by the observed accounts during the six-month periodis the main object of our research. To identify posts related to the pandemic within this dataset and differentiate them from tweets about other topics, we implemented an automated content analysis approach based on 19 word stems. This analysis found that 81,719 out of 254,238 tweets could be classified as relating to the pandemic with reasonable certainty.

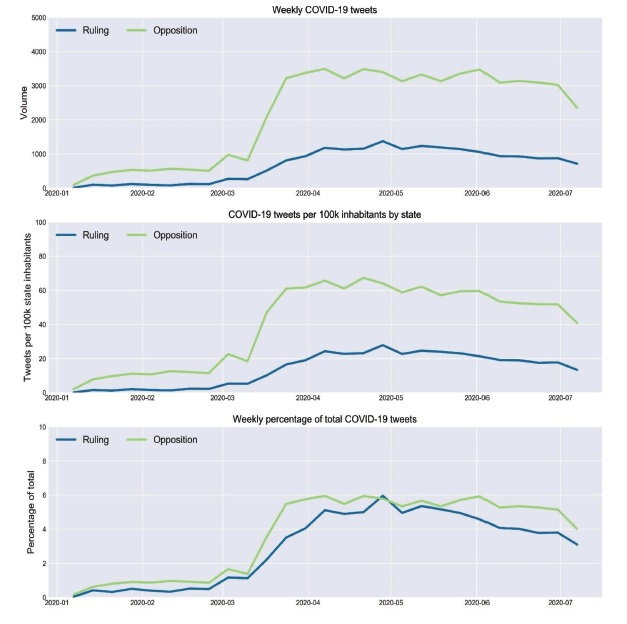

Figure 1 presents comparisons between the weekly volume of contingency-related tweets by members of the ruling parties and members of the opposition. The green lines represent the amount of Covid-19 tweets posted by opposition officials per week during the observed period. The blue lines represent the same metric, for ruling bloc officials. The top plot presents the raw weekly amount of tweets. On this graph, we can see that there is a sharp increase in Covid-19 tweets from opposition officials after the first week of march. This increase is also present, albeit nowhere near as dramatically, among ruling party officials. The second subplot compares the amount of contingency-related tweets per one-hundred-thousand state inhabitants. The purpose of this second categorization is to account for the difference in population size from state to state: as was to be expected, states with larger populations, such as Estado de México, had a much larger gross output of Tweets than other smaller and less-populated regions. Quantifying the output per 100k inhabitants allows us to have a point of comparison that accounts for such differences, and it’s particularly useful as a complement to the gross amount of tweets, per the first subplot. The marked similarity between both graphs confirms that the difference between the two lines doesn’t simply answer to a difference in population size. The bottom plot depicts the weekly percentage of total publication: that is, what percentage of the total amount of tweets emitted for the observed period were tweeted that particular week. This allows us to see much more clearly the differences in activity, regardless of the amount of publications. In this third plot, we can see that the ruling bloc’s publications had a slower increment of Covid-19 related tweets during march -the crucial period for this researchthen an apex at the end of April and a swift decline, remaining approximately 20% lower for most of the period. In summary, the graphs show that the opposition had a much larger output of contingency-related tweets, both gross and relative to the state’s population, and a swifter and more constant increase in communication after the first confirmed cases in the country.

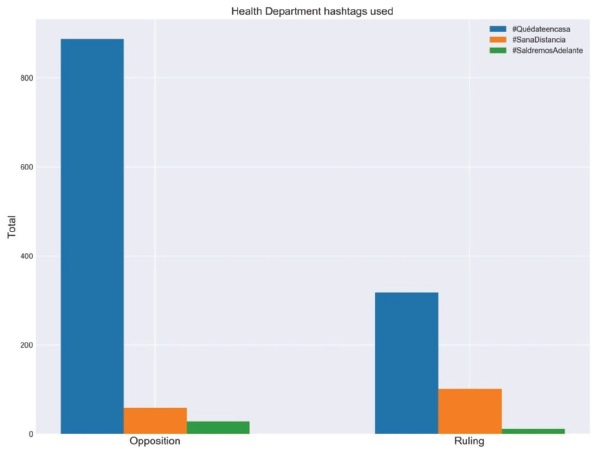

We can perceive in the graphs that the opposition had a sharper, swiffer increase in communication during the month of march, when the disease started spreading in Mexico. We hypothesized that the President’s skeptical stance might be related to the absence of this sizable uptick in communication (on top of the lower posting volume) on the part of ruling party officials. Starting from this hypothesis, we analyzed both López Obrador’s and the Health Department’s twitter feeds during the six-month period. Through word count reports, we identified three hashtags that were heavily promoted by the Health Department during this time: #QuédateEnCasa (‘stay at home’), #SanaDistancia (‘healthy distance’) and #JuntosSaldremosAdelante (‘together we shall overcome’). To account for variation, these hashtags were reduced to the stems which were common to all their variants: teencasa, dremosadelan, and sanadistancia. As we can see in figure 2, the opposition used two of the three hashtags more frequently by a large margin, more than doubling the use by ruling party accounts. While counter-intuitive at first glance (the Health Department, after all, is part of the ruling party’s administration), this is consistent with the hypothesis that the president’s discourse had a chilling effect on the ruling officials’ COVID communication. It’s also consistent with similar phenomena in other countries with populist leaders (Campos, 2020; Dyer, 2020; Lancet, 2020; Rutledge, 2020), in which the leader’s discourse directly contradicted and undermined the administration’s own health experts.

The next step was to establish the link between the president’s rhetoric and the ruling party’s tweets. For this, we employed an approach based on supervised machine learning. These types of approaches are becoming more and more common as a methodological tool to track and analyze the adoption and reproduction of discourse in social media, and it has become particularly relevant in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, when a fast analysis of data is crucial: the work of Xiang et al (2020), Li et al (2020), Wahbeh et al (2020), Samuel et al (2020) and Green et al (2020) are a few stand-out examples of the trend of employing machine learning to classify social media data during the Covid-19 pandemic.

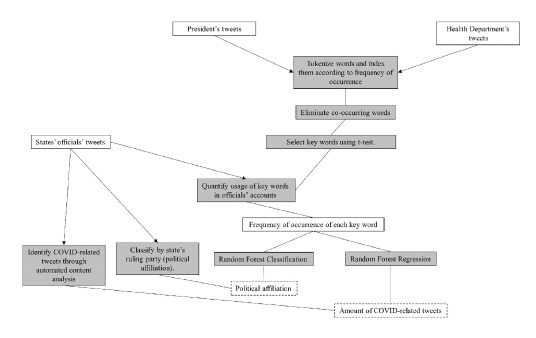

For this study, we employed natural language processing to tokenize the words in the tweets by the personal account of López Obrador on one side and the Health Department’s official account on the other, and then used the most characteristic words employed by each account as predictors of political affiliation and of Covid coverage in the officials’ accounts (figure 3).

Specifically, our approach employed bag-of-words representation, which simplifies the text by representing it as a multiset of the words that it contains, weighted by frequency of occurrence (Deepu et al., 2016). Because bag-of-words is a unigram model, text is divided into one-word units (or ‘tokens’), and the number of instances of each word is recorded, independently of context and function within the text itself. We also employed random forest classification and regression. Random forest is a method for classification and/or regression that expands on the decision tree predictive model by creating a large amount of independent decision trees (a ‘forest´) from different bootstrap samples of the data, and outputting either the mode class or mean of the output of each individual decision tree (Liaw and Wiener, 2012). When it comes to natural language processing, Naïve Bayes and Support Vector Machines (SVM) are often regarded as the two models with the highest accuracy (Kharde and Sonawane, 2016; Nayak and Natarajan, 2016; Tóth and Vidács, 2019); however, the relative generalizability (i.e. its resistance to overfitting) of the random forests model has proven to be very effective for identifying and classifying authorship of corpora on Twitter (Adewole et al., 2020; Simaki et al., 2016). This is why the model has seen an increase in authorship-classifying tasks with Twitter data, including spam and bot detection (Adewole et al., 2020; Chu et al., 2012; Schnebly and Sengupta, 2019), and classification of human users (Palomino-Garibay et al., 2015; Kwon et al., 2018; Simaki et al., 2016).

After tokenizing the text in the tweets posted by both the health department’s and López Obrador’s accounts, all co-occurring features (words appearing in both accounts) were discarded, so that only words exclusively used by either one of the two accounts remained. Stopwords (common words and punctuation) were also discarded. Once the text was tokenized and sorted according to frequency, the fifty most frequent words in each list were collected in an array of 100 items. Each tweet in the dataset was queried for the presence of each of the 100 words, and a dataframe was created with the total of occurrences per word per account.

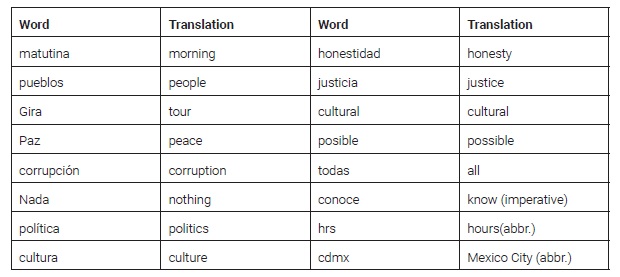

In order to effectively use the bag-of-words representation as input for prediction, it is useful to reduce the set (or bag) to the highest-value features or the ones most likely to inform the predictor correctly, employing a criterion for hierarchization or inclusion. George and Joseph (2014) and Sayeedunnissa et al. (2012), among others, use the chi-square test to select keywords or unigrams. In this case, because the words are used as covariates both in classification and regression, we used an independent sample t-test instead. The test compared the mean occurrences of each word on accounts belonging to ruling party and opposition officials, and found that 16 of the 100 words were significantly correlated (i.e. had a p-value equal to or below .05) to the account’s political alignment. In table 2, we can see the words and their translation.

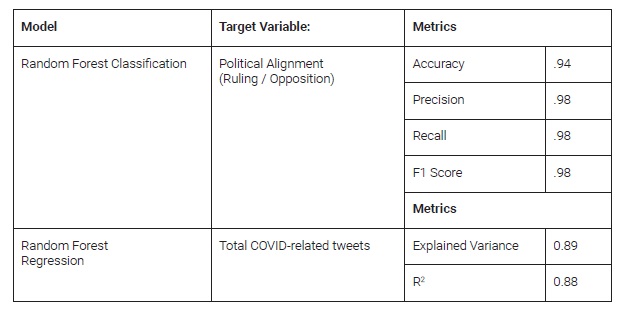

These 16 words (table 2) were then used as covariates to train a random forest classifier to predict the accounts’ political alignment. The model employs the ‘gini’ criterion as a metric for the quality of the node splits, with 16 estimators and a maximum depth of 10 decisions. These parameters were decided by performing an exhaustive grid search for the best cross-validation score. After training and testing the model, we obtained an accuracy of .94, with a precision, recall and F1 score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall) of .98. This suggests that presence of these words in a corpus of tweets is a very reliable predictor of the tweeting official’s political alignment, cementing the notion that the president’s discourse permeates the officials’ communication on the social media platform.

Having established that there is a correlation between use of these words and political alignment, we used the words again as covariates for a random forest regression model, aiming to predict the amount of COVID tweets posted by each account. This second model uses mean square error as a criterion, with 8 estimators and a max depth of 8, also selected through an exhaustive grid search. After fitting, the model’s explained-variance score (the proportion to which the model explains the variation in the data) is .89 and its coefficient of determination (R2) is .88. This suggests that use of these words is a reliable predictor of the number of COVID-related tweets posted by an account.

Going back to table 2, we can see the frequent words in the president’s discourse that were used as reliable predictors. These words have two things in common: many of them are commonplaces of populist rhetoric (Chilton, 2017; Naxera and Krčál, 2019; Müller, 2017) and all of them are entirely unrelated to the pandemic. That these hazy terms often employed in populist discourse are a reliable predictor of the poster’s political affiliation might not surprise us, as we’ve established that López Obrador has a distinctly populist rhetoric, and it is somewhat expectable to find traces of the same rhetoric in members of his party. But the fact that the same words also reliably predict the amount of health-related communication is a grim reminder of the extent to which presidential discourse can affect an administration’s functioning.

Discussion of Findings

This study set out to investigate the relationship between President López Obrador’s skeptical discourse on Covid-19 and the use of Twitter by state officials for communication about the pandemic. First, the study found significant differences in volume of Covid tweets between officials of the opposition and the ruling party, with the party-aligned officials tweeting much less about Covid-19 during the entire six-month period. Second, the study revealed that the Health Department’s pandemic-awareness hashtags were underused by ruling party officials, even though the Health Department itself is part of the ruling party’s administration, pointing again to a lower amount of communication on the part of Morena state officials. Third, our supervised machine learning models are effective in measuring the use of certain high-frequency words of the president’s Twitter as a predictor not only of political affiliation but also of volume of Covid tweets. Furthermore, the words that proved to be most strongly correlated and the best covariates for prediction turned out to be common staples of traditional populist discourse centering on the binary of the untainted people versus the corrupt elite. This leads us to believe that the underper-

formance of ruling party accounts is indeed strongly related to the president’s own populist discourse and dismissive stance towards this emergency, directly against his own health department’s recommendations.

As we’ve seen in the previous section, our study found that the most frequent words in the president’s discourse during the pandemic were a reliable predictor of an underperformance in state officials’ communication. These findings are consistent with similar phenomena in other countries with populist leaders (Campos, 2020; Dyer, 2020; Lancet, 2020; Rutledge, 2020), in which the leader’s discourse directly contradicted and undermined the administration’s own health experts. Furthermore, our findings corroborate the concerns expressed by other studies, to the effect that the president’s discourse could prove detrimental to the country’s efforts to cull the pandemic. Given the president’s anti-establishment stance and insistence on demonizing technocratic experts -what Rentería & Arellano-Gault call “downsizing populism”-, we could assume that not only have the president’s words undermined his own Health Department, but they could have provoked similar phenomena -of decreasing trust in health institutionsat a state and regional level, considering the evidence we now have regarding his influence on the treatment of Covid-19 communication among his officials. Lasco (2020) has coined the term ‘medical populism’ to refer to the attitudes of Bolsonaro, Trump and Duterte during the pandemic. The characteristics they list (downplaying the danger, creating division and peddling easy pseudo-remedies) are consistent with López Obrador’s discourse. Our findings allow us to ascertain that said discourse does indeed have consequences, even if it is not accompanied by actions. In this case, the consequence is a chilling effect on the coverage of the pandemic on Twitter by state officials aligned with the regime. The problem is that a lot of the literature on this particular topic treats this ‘medical populism’ as a trait of right-wing or ‘conservative’ regimes -see Labonte & Baum (2021), Stecula & Pickup, (2021), Wang & Catalano (2022)-. López Obrador, as we’ve seen, is a center-left leader with markedly left-leaning rhetoric, which evidences the fact that contemporary populism is far from exclusively a right-wing phenomenon.

Furthermore, we’ve established that many of the words most repeated bv López Obrador -that have proved to be reliable predictors of a chilling effect on COVID communicationare consistent with commonplaces of populist rhetoric (Chilton, 2017; Naxera and Krčál, 2019; Müller, 2017). The fact that these words are often employed by populists of both left and right-leaning tendencies helps us conceive of populism as a discursive tool that isn’t necessarily linked with any particular ideology, but rather with a Manichean proposition of the good people versus the evil elite.

Some of the predictors obtained through this method are in fact words used by López Obrador in his downplaying of the epidemic during his daily nationally-televised briefings. The fact that echoing these words is correlated with a lower rate of COVID communication on social media by state officials is frankly disheartening, given that these are the very officials in charge of promoting awareness and appropriate safety protocols among the population.

As for the limitations of our proposed method, we’ve already mentioned that this paper and its findings are part of a broader observatory concerned with the treatment of the pandemic in Mexican official social media, and as such we’ve had to design methods that best take advantage of the available data as-is, rather than tailor our data collection to better capture the studied phenomenon. This is particularly limiting for our study if we take into account that research of populism as a discursive framework usually analyses text within its context. As Aslanidi posits, a good method for measuring populism must “use a coding unit that strikes a balance between incorporating context and allowing for significant semantic resolution” (2018, p. 11). Although our goal was not to measure populism in the discourse of López Obrador, but to measure the influence of said discourse on the communication of state officials, we still must keep this problem in mind for subsequent research. Thus, while the bag-of-words model yielded, in our opinion, sound and definitive results for the objective we set out to achieve, further research with the express purpose of measuring populism might benefit from tokenization techniques with a more ample clause type, such as n-gram or Regular Expressions. At the end of the day, though, every type of tokenization -and the idea of natural language processing in the study of populist discourse itselfis in itself a compromise, and a well-rounded content-analytical research project on this subject ought to rely on a concatenation of quantitative metrics and qualitative approaches (Aslanidi, 2018). In the case of this paper, we are aided by the fact that López Obrador’s discourse both on Twitter and elsewhere during this precise period, as we’ve established. The studies in question not only found that the president’s discourse was indeed populist, but already theorized on its possible impact on the performance of health institutions. This provides us with a degree of certainty that our approach is not taking the president’s words out of context or misconstruing their possible consequences.

The findings of this study illustrate not only the chilling effect that the president’s discourse can have on the dissemination of vital information, but also the way in which a populist anti-technocratic government can informally limit the agency of their own experts through discourse alone. As we’ve seen, Manichean rhetoric, emotional communication and limiting the participation of technocratic policy experts are all strategies of the populist policy model (Bartha, Boda and Szikra, 2020) that are clearly identifiable in the way López Obrador’s government has handled the pandemic and undermined their own appointed experts.

It is in times of crisis when we need strong, efficient institutions. Even as the pandemic buffets national economies and democracies the world over, strongman politicians continue to dictate policy to their parties and followings outside of the proper channels, under the guise of informal speech. More often than not, this policy calls for the dismantling of democratic and administrative institutions. From the gutting of the USPS (Kauffman, Cohen and Huffman, 2020) and the FCC (Masur and Posner, 2020) in the US to the attack of Johnson’s regime on British healthcare (Lawrence, Gardside and Pegg, 2020), systems of government are undermined at every turn by appointed politicians with populist discourse. In some countries, these systems are resilient enough to weather the storm. In Mexico (and most of the Americas), they’re not. Our institutions are fragile and incipient. They need to be defended.

When we look back at this global tragedy, the role of populist regimes throughout the world will be one of the key factors to analyze, without a doubt. It is no coincidence that the highest death counts come from countries with populist, authoritarian governments. The deliberate dismissal of science and procedure are not without a price. Sadly, the lion’s share of this price is paid, as always, by the disenfranchised.