Almost two decades ago, Gianpietro Mazzoleni anticipated that the “full understanding of the populist phenomenon cannot be achieved without studying mass communication perspectives and media-related dynamics” (2003, p. 2). Since then, the communication-centered approach to the populist zeitgeist has progressively become a salient topic of discussion in academic scholarship. But the focus of extant literature has often been the “media factor” or the media’s complicity as producer and facilitator of populism upsurge. A less studied role of mediated communication is that of the press being critical or adversarial of populists. And the critical investigative reporting scrutiny of the far-right populism is yet to be investigated.

Against this backdrop, the Portuguese case provides an ideal illustrative example of the under-researched topic of media critical responses to the populist radical right. Beyond anecdotal evidence of the routine coverage of previous works, this study examines the degree of adversariness towards populists published in news content of the investigative reporting in a recent but overlooked example of a Southern European democracy. Besides determining the kind of criticisms and their sourcing, it also constitutes a unique opportunity to examine the extent to which diverse news outlets belonging to distinct segments of the upmarket investigative reporting within the same country can differ in their approach to far-right populism.

To achieve this, it proposes a mix-method comparison of the investigative journalism dynamics across media sectors. A fine-grained content analysis of both the substantive focus of the criticisms and their sources in the Portuguese investigative reporting of the emerging far-right populist party Chega (Enough!) is complemented with reconstruction interviewing with the reporters involved in the coverage. It concludes that media dynamics related to the investigative reporting genre justify the level of journalistic adversariness towards populism.

The article begins with a theoretical discussion of the critical reporting of far-right populism to frame the study and formulate the research questions concerning the level of media adversariness. Next, it contextualizes the Portuguese case study and accounts for the methodological choices before presenting and discussing the findings.

Media as a platform of far-right populism

In response to repeated requests to place communication at the center of the systematic analysis of populism as one of the hallmarks of contemporary politics (Aalberg et al. 2017; Mazzoleni, 2003), a major strand of the recent studies has attempted to determine the possibility of the media to have a role in the successful dissemination of populist messages. Indeed, either indirectly and unwillingly, or directly and purposefully, media may contribute to the establishment and normalization of populist actors and ideas (Aalberg et al., 2017; de Vreese et al., 2018; Esser et al., 2017; Ernst et al., 2019; Ferin, 2019; Hafez, 2017; Krämer, 2018; Serrano, 2020; Salgado et al., 2021; Stanyer et al., 2016; Wettstein et al., 2019, to name a few).

In alternative to the media being populist themselves or amplifiers through providing a stage for populist messages and actors (Mazzoleni, 2014; Krämer, 2014), a less pursued sub-strand of research relates to the press playing an instrumental role in limiting the spread of populism (Boomgaarden & Vliegenthart, 2007; Hafez, 2019; Hameleers et al., 2017).

Still, the existing academic evidence of media critically engaging with far-right populism and serving as a platform to restrain and challenge populist political communication has come in different forms. Scholars have previously acknowledged that populism is not overrepresented overall and tends to be evaluated negatively in routine news reporting (Esser et al. 2017; Herkman, 2017; Mazzoleni, 2008; Salgado et al., 2021; Wettstein et al., 2018), at least in the tone (Herkman, 2017) and mostly within the opinion or commentary sections (Esser et al. 2017). Another possibility found in the extant literature is to include populist messages in the news reporting, but only to criticize, deconstruct and refute its content (Blassnig et al., 2019). Also, a recent study based upon a series of semi-structured interviews with editors-in-chief and journalists of traditional media outlets refers that media practitioners may opt for a confrontational approach vis-à-vis the populist radical right (de Jonge, 2019). Consequently, media professionals may distance themselves by exposing the true colors of populists and delegitimize them through news coverage that demonizes or stigmatizes them, and, in the extreme, elite or quality media can be particularly critical of far-right populist parties (de Jonge, 2019; Mazzoleni, 2008; Salgado et al., 2021).

Ironically, such negative coverage does not appear to affect populist parties that much (Esser et al., 2017). Quite the opposite, the critical scrutiny of populist actors may even contribute to their success. To start, populist actors need the “oxygen of publicity” (Mazzoleni et al., 2003) supplied by the media. While the media are critical, the populist actors dominate the news agenda (Hafez, 2017) and increase their visibility. So, there is no such thing as bad press for them. Rather opportunities to “fuel greater visibility by responding in ways that both the hostile and friendly media cannot ignore” (Mazzoleni, 2014, p. 52). Given that far-right populist actors thrive on antagonism and conflict (Mudde, 2007), they frequently turn hostility from the mainstream media into their communication purposes (Jagers & Walgrave, 2007). Not only do they use media’s critical coverage as proof of political weight and legitimacy (Wodak, 2015) but also to fuel their chronic accusation against the mainstream media of being “opponents who restrict their speaking opportunities and attack their positions and personnel” (Wettstein et al., 2018, p. 477).

The likelihood of critical reporting boosting populist actors does not exempt the media, however, from a counterbalance normative role of actively signaling and correcting or opposing any democratic dangers for democracy (Schmidt, 2020). Despite the burgeoning evidence of media critically engaging with far-right populism and serving as a platform to restrain and challenge the populist political communication, the level of adversariness as evident in the nature and the extent of the press criticism against populists, however, remains poorly understood (Benson, 2010). Moreover, although a few studies on critical reporting have focused on investigative journalism (Chalaby, 2004; Glasser & Ettema, 1998; Marchetti, 2009; Schudson, 2008; Waisbord, 2000), the performance of the specific genre in the critical conveyance of populism across media is yet to be researched.

Given the limited body of theory and research in the literature and against the theoretical discussion outlined above raises specific questions to empirically address within the context of the explorative study of Portuguese investigative reporting of populism under examination:

The reporting of the far-right populism in Portugal

Until quite recently, the legacy media reporting of the far-right populism in Portugal has been a scarcely researched topic and it tended to be more asserted than empirically verified (Salgado & Zúquete, 2017; Serrano, 2020). Although some historical idiosyncrasies of the country and the parties account for the hardship of the far rightright populist to succeed in the country’s politics such as the lingering inheritance of the Salazar dictatorship period, the absence of significant securitarian or identitarian “owned” by the far-right (da Silva, 2018), and the far-left parties functioning as safety valves of societal discontent (Salgado, 2019) another factor of interest to this work outweighs those contextual circumstances. It is hereby posited that all other things being equal, a pivotal explanation resides on the fact that previous existing fringe parties with a radical right agenda in Portugal have been unable to present themselves as credible political alternatives (Mendes & Dennison, 2021). And the National Renovator Party (PNR), rebranded to Rise Up (Ergue-te) in July 2020, stands out as a paradigmatic example in this respect. Since its inception in 2000, the party was unable to elect any deputy given its modest results - the best score being 0.5% in the 2015 general elections and a similar score in the 2019 European Parliament ballot.

Hence, it suggests a distinction between two different periods ranging from before the current era (BCE) and the current era (CE) marked by the advent of Chega in 2019. Indeed, those periods displayed rather than contrasting strategies by the farright populist parties that impacted the way the media in Portugal dealt with those political actors and consequently the academic research on the subject. During the BCE years, the Portuguese media established a cordon sanitaire to demarcate itself from the right-wing populists. When not truly ignored, populists were isolated and given a ‘differential treatment’ by the press like other countries (de Jonge, 2019). Besides the reluctancy to cover populism, quality newspapers and mainstream television channels also displayed hostility toward populism by attempting to “critically deconstruct it’’ (Salgado & Zúquete, 2017, p. 242). The justification for such a media cordon is twofold: it mirrored the politico-societal perception of populism in Portugal at the time as well as the representativeness of the populist party and actors in the national setting; and it was proportional to the efforts by far-right parties to enter the news agenda and grant media visibility.

Regarding the former, the media cordon but extended or replicated the political cordon by the main established parties to exclude the right-wing newcomers from mainstream politics to prevent their spread. As for the latter, it should be mentioned the inability of both the PNR and its leader, José Pinto Coelho, to get the message across to the mainstream media or to use the alternative of social media. Thus, the party visibility depended upon the goodwill or lack thereof of the TV and newspapers (da Silva, 2018). When it eventually did get some news attention, most during the election cycles, it amounted to negative media coverage that usually conveyed the PNR as ‘‘an extremist group nostalgic for the former authoritarian regime’’ (Marchi, 2013: 150). Not without consequences, though, given that some authors even correlate the mainstream media’s reluctance to cover the PNR with the limited or nonexistent electoral success (Salgado et al., 2021).

With the advent of Chega and its first breakthrough with its leader, André Ventura, secured a seat in the national parliament at the 2019 general election, the media’s limelight on the far-right definitively diverged from the PNR to the newcomer (Marcelino, 2020). Ventura made a name for himself as a football TV commentator in supporting the most representative club in the country. Such a constructed media celebrity was further complemented by the notoriety as a political persona when he accused the Roma people of living on state benefits during the 2017 campaign for the municipal elections, still as a candidate for the center-right Social Democratic Party (PSD). The Roma sound bite granted ample news coverage and resonated within the electorate would inspire his future media strategy as leader of the Chega. It consisted of sparking polemic and fierce debate in the public sphere from the outset, through the employment of emotional and controversial messages (da Silva, 2018) to attain visibility by legacy media in either featuring in the frontpages or making into the headlines (Marcelino, 2020). Two examples suffice to illustrate the point. First, by suggesting that the afro-descendent MP born in Guinea Bissau, Joacine Katar Moreira, to be returned to Africa during the debate on the repatriation of artifacts removed from former Portuguese colonies (Dantas, 2020). Or, when emulating Trump in a tv debate with the incumbent candidate for the 2021 presidential elections, by using a photo of Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa with an Afro family in the Jamaica neighborhood in the outskirts of Lisbon as evidence of him “siding with bandits” (Melo, 2021) whereas Ventura would only be the President of “the well-intended” Portuguese (Fernandes & Teles, 2021).

Furthermore, Ventura also opted to develop a digital strategy to circumvent the mainstream media to strike the anti-establishment chords (Mendes & Dennison, 2021). A somewhat charismatic and verbally skilled leader supported by a professional communication strategy helped him to build a loyal constituency facilitated by the leading tabloid newspaper Correio da Manhã and its twin brother 24 hours sensationalist news channel CMTV (França, 2019). The few scholarly works on the matter concluded that both political and media visibility significantly increased in tandem following his election as a member of the national parliament and peaked when he campaigned for the 2021 presidential election (Palma et al., 2021), and detected some of the customary marks of populism in the media reporting (Serrano, 2020). But Chega’s mainstreaming not being excluded from participating in the political process and the news agenda did not prevent an overall antagonistically tense relationship with the upmarket media (Marcelino, 2020). And unlike previous fringe parties in Portugal with a radical-right agenda that prompted no investigative journalistic work, Chega was about to be the target of an unprecedented confrontational approach by Visão followed suit by SIC.

Methodological options

The study employs a qualitative multi-method that combines content analysis with interviews to address the research questions. It comprises a within-case comparison of two mainstream news outlets, the SIC television network and the weekly newsmagazine Visão, as a representative sample of the generalist quality press devoted to investigative reporting. Besides leading their respective segments and reaching critical mass audiences (Schlosberg, 2017), they were also chosen for displaying a commitment to investigate populist actors (Zelizer & Allan, 2010). To the author’s knowledge, no previous work has endeavored to jointly analyze newsgazine and televison reporting of populism.

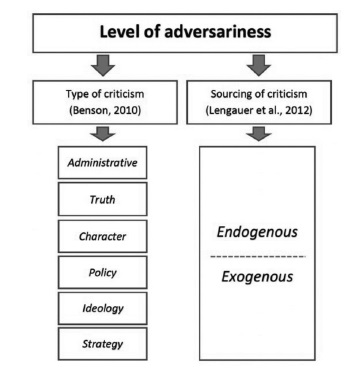

Moreover, the study draws on prior conceptual and operational definitions, with some adjustments and refinement, to assess the level of adversariness in the investigative reporting of far-right populism through a content analysis focused upon two dimensions: the kind of criticism (Benson, 2010) and the sourcing of the criticisms within a unidimensional structure ranging from the journalistic “endogenous” initiative (or own words) to merely quoting either actively or passively other “exogenous” sources in the reporting (Lengauer et al., 2012).

Figure 1 Operationalization of the adversariness in investigative reporting (adapted from Benson, 2010 and Lengauer et al., 2012)

Assuming that not all criticism is the same and that a distinction should be made between the sourcing of the critical statements, this study focuses on the visible manifestations of adversariness within the Portuguese investigative reporting of the far-right populism by distinguishing between six content indicators of the type of criticism1 and the sourcing of the criticisms. First, administrative criticisms refer to improper implementation or failure to execute legal or administrative responsibility. A good example of what is considered as this type of criticism concerns the “1813 illegal” signatures detected during the process to officialize the Chega party back in April 2019, as reported by SIC on January 11. Second, truth criticisms consist of evidence to demonstrate the falsity of claims and setting the record straight, such as the debunking of an “alleged invitation for Ventura to participate in Trump’s convention” that turned out not to be so within Visão’s September edition. Third, character criticisms include personal characteristics of party leaders like the repeatedly depicting Ventura as an “opportunist” in the newsmagazine published in May that also constitutes an illustrative example of “endogenous” or journalist-initiated criticism (or own words). Fourth, policy criticism concerns the logical coherence, feasibility, or empirical justification or evidence supporting any proposed policy as well as deviation from legally mandated procedures. For instance, a negligible reference to Chega’s proposals to include chemical castration of child sexual offenders or the penalty of life imprisonment in the country’s legal code. Fifth, ideology criticisms allude to objectionable connections to fascism, racism and other, and, lastly, strategy criticisms encompass normative judgements of overt or covert “too negative,” “dirty,” or in some other way morally objectionable political strategies. While elaborating of the prevailing factions within Chega, a researcher on populism quoted in the December issue of Visão, Alexandre Carvalho, offers elucidating examples of both the former the party portrayed as a “widow of neo-liberalism” with connections to the far right, the latter blends “the conservative and ultra-conservative” and the latter Chega’s supporters comprising of the “political disgruntled, the opportunist, and the careerists” constitute a “Trojan horse” aiming at the democratic establishment. Or in apparently neutral sentences conveying associations that backlash against Ventura as when alluded in May that he considers “Salvini to be his role-model” despite seeing “qualities in Trump and Bolsonaro” also implicitly portraying him in a negative light. The aforementioned ideology and strategy criticisms also constitute examples of “exogenous” criticism originating from sources other than the journalist’s own words.

The corpus of data to be subjected to the empirical study encompasses all the stories from Visão’s printed editions from my database dedicated to Chega 1420 (2020, May 21), 1429 (2020, July 23) and 1449 (2020, December 10) comprising a total of 36 pages and 19 news texts most of them (long) feature articles. Although not included in the analysis for being different journalistic genres from the investigative reporting editorials and opinion articles are also incorporated into discussion as supporting material to the conclusions. In terms of the SIC’s material2, it comprises 166 minutes of recorded material over five programs aired in the prime-time night news over two consecutive weeks of January 2021 (5 and 11) during the campaign for the presidential election and then the three remaining editions broadcasted in April (1, 6 and 14). The unit of analysis is any critical statement targeted at Chega or its leader coded alongside identifying the sourcing of the critique to whom reporters turned to for their reporting, including their own words. The laborious process of data collection and codification by a single researcher paved the way for invest the raw numbers with meaning. That is, the findings are described and interpreted in terms of their significance to the study. Lastly, a comparative reconstruction of the investigative coverage from the authors of the reports on Chega is advanced (Brüggemann, 2013; Mc Manus, 1997). It consists of qualitative semi-structured interviewing of the two journalists through asking them to reconstruct the stories behind their investigative reporting regarding the instigator and timing of the news story and the journalistic practices involved in the level of adversariness. Then, it uses some trends of the analysis of their far-right populism coverage as further evoking devices of the criticism’s reconstruction discourse. A verbatim transcription of the recorded interviews conducted in March and May 2020, precedes the identification of similarities and contrasts across the statements focused on the type of and the sourcing of criticisms. When employed in the study, the content of both the reporting and the interviewing is translated from the native

Portuguese into English by the author.

Findings

Overall, the criticisms related to ideology and strategy (both with 32%) prevail by far in the Portuguese investigative reporting of Chega followed by less frequent reproval regarding the character (14%), administrative (10%), and truth (9%). Lastly, censures concerning policy issues only feature scarcely throughout the reporting (2%). Another striking result of the analysis other than the somewhat significant difference between Visão (42%) that integrates only three editions against the five-episode series of SIC (58%), is the overall mismatch between the type of criticism in the reporting. In fact, Visão and SIC only coincide in not granting major importance to policy criticisms (1%). Then, whereas the former is more critical of administrative issues (6% versus 4%), the latter targets with greater intensity the ideology (20% versus 12%) and strategy (19% versus 13%) topics, as well as doubles the efforts to set the record straight (6% versus 3%). Regarding the sourcing of the criticisms featuring in the reporting, the media-initiated critics dominate the coverage to the detriment of

the ones originated from other sources in the news reports (63% versus 37%).

A more fine-grained analysis beyond the mere frequency of the type and sourcing of the criticisms further explores the adversariness and the journalistic initiative in the reporting. The analysis of the criticisms in the reporting starts with the negative or morally objectionable strategies and reveals that both Visão and SIC portray Ventura’s questionable master plan of dividing and rule. To achieve it, they have no qualms to quote several party dissidents as conveying most of the critical remarks. For instance, the episode surrounding a national leader’s, Patrícia Sousa Uva, resignation from the party as a result of the internal unrest, and the “gag law strategy” or the “code of silence” imposed by Ventura to prevent the frequent offenses amongst Chega affiliates. As described by himself in SIC’s January 5 episode, it involved “denigrating party leaders, death threats, insults of the worst kind and considerations of a criminal nature.” Visão even signals in its December edition the paradox of a party that publicly claims against be silenced, ending up silenced from within.

Chega frequently features as a house divided against itself with several internal controversies and turmoil. Visão, for instance, recalls in the May edition Ventura’s words when he threatened to resign, acknowledging the “threats, humiliations, personal hatreds” from fellow party members that are claiming that “we went too extreme and had to moderate” by countering with the “line and origin” of the party that the “Portuguese request and want us to perform” without” fear or only half-hearted.” Visão also denounces a series of conflicts in Porto, the Algarve, and Madeira Island, revealing the prevailing tension and the resulting threats of leaving the party, evidencing a thorough ground investigation by the reporter. Another investigative topic of Visão’s reporting concerns Chega’s digital strategy when conveying in a critical light the use of fake Facebook profiles. As early as in the May edition, the head of a strategic digital consultancy agency estimates the existence of “20 thousand fake profiles”. Then the issue is revisited in September, through the former leader of the Southern Algarve region, Rui Curado, validating the deliberate strategy of creating fake Facebook profiles or by the regional newspaper Correio do Minho identifying other pages and thousands of shares originated from the “army of fake profiles” in a follow-up story. In its turn, SIC dedicates plenty of the first episode to disclosing Ventura’s backstage maneuvers to get re-elected in the September 2020 Chega convention described as “burlesque theater.” “Acting as an illusionist,” Ventura managed to: “transform less than half of the delegates in two thirds, to conceal the behind-the-scenes games, and hide the marks of all the stabbing in the back, leading to it the greatest illusion of transforming the Party in which only he decides into the party of its militants.” Later, Luisa Semedo is used on the episode to convey Ventura’s strategy “to resort to polemic declarations” on some polarizing issues aiming for their progressive “normalization.” Furthermore, both reporters convey strategy criticisms in their own words. Visão’s December issue wonders whether Chega should be regarded “as a political affair or a police affair” sensing that the party is “about to implode” for experiencing “an unlikely and premature state of civil war (…) with an anticipated sulfur and death smell in the air (…) unveiling from North to South the traits of a political underworld that Ventura promised to fight against.” Pedro Coelho employs a similar metaphor by placing the party’s strategy in the “dark catacombs of politics”, characterized by “hate speech, insults, and low politics”. Lastly, there is a lingering criticism on Ventura’s strategy to sell himself as a God messenger”, by frequently associating him with either a false messianic figure (both in Visão and SIC) and an untrustworthy preacher (mostly in Visão and as illustrated in the front page of the May’s edition).

As in the strategy criticism, the religious dimension is also a pervasive facet of the ideology criticisms. SIC and Visão focus on the parallelism with the Portuguese conservative catholic tradition, particularly in the television third episode of the series related to the similarities with the former Portuguese dictator’s (Salazar) motto of “God, homeland, and family”, as well as in the December edition of the newsmagazine with the academic Alberta Giorgi disclosing one the party’s vice-presidents, Diogo Pacheco de Amorim, as belonging to the political powerful Communion and Liberation movement said to be “more active than Opus Dei.” Visão further extends the religious blends of Chega with the Brazilian-originated ultra-conservative evangelic denominations. In May, the sociologist Donizete Rodrigues identifies within the pages of Visão a reciprocal relationship between the evangelic denominations and the party in which the formers aim at “expanding their neoliberal agenda, conservative, populist, far-right, racist, xenophobic, nationalist and homophobic”, and the latter seeks financial support and “political power.”

Other politico-ideological criticisms appear in the reporting alongside the religious factor. SIC, for instance, dwells on the racist and xenophobic nature of the party either by debunking Ventura’s narrative towards the Roma community and disclosing Chega’s involvement in a racist protest held in Lisbon (both in the first episode) or by including sources in the report that depict him has been able to “send a fellow member of parliament back to his country and get away with it” (fourth episode). The researcher on populism, Alexandre Carvalho, also depicts Chega in Visão as a sort of “widow of neo-liberalism” with connections to the far right, that co-exist with a “fringe” of people comprising of the political disgruntled, the opportunist, and the careerists”. In similar terms, the evangelic pastor, João Viegas, defines Chega within the December edition of the newsmagazine as a “messy mix, a catalyst of resentment and despair, employing political bullying as ideology”.

Far more frequent, though, are other stigmatizing connections to fascist and Nazi ideologies attesting to the radical facet of the party. Both Visão and SIC coincide in attempting to make the case of the links of a party leader, Luis Filipe Graça, to neo-Nazi groups through the quoting of Sábado newsmagazine as their source. But differences also surface in the reporting since Visão opts for blending the nationalization and internationalization of the comparative examples while SIC chooses the Europeanization and historicization of the affair. Visão relates one of Chega’s vice-presidents and ideologists, Diogo Pacheco de Amorim, to a far-right bomb network (Democratic Movement for the Liberation of Portugal - MDLP) during the agitated years following the 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal that followed the end of the dictatorship in the country. Furthermore, the former security coordinator of Chega, Bento Martins, is also mentioned in the newsmagazine confirming the habit of a “neo-Nazi dunghill” escorting the party’s public activities and further complemented in the coverage with the association with notorious national extremist violent groups (the neo-Nazi’s New Social Order/NOS and National Opposition Movement/MON). References to Nazi salutes during the party activities pop up less often in the newsmagazine reporting alongside occasional mentions to the likes of Ventura such as Mateo Salvini, Jair Bolsonaro, or Donald Trump. SIC inserts Chega in the past context of the Portuguese Salazar ruling and Franco’s Spain and Mussolini’s Italy. The European parallel is also employed to make the case of a dangerous contemporary trend with a particular emphasis in France, Italy, and Spain and Marine Le Pen, Mateo Salvini, and Santiago Abascal, respectively. It becomes a sort of a story inside the news reporting within the third and fourth episodes of the investigative series.

Character criticisms to Chega’s party leaders, particularly Ventura, feature throughout both Visão and SIC and do not dissociate with their political personas. Namely, party dissidents portray Ventura as a “fraud,” “a crook able of selling sand like water,” or “constantly saying one thing and doing another” Members of the Roma community also accused him of “having no respect for anyone nor himself” (SIC’s first episode). Up to the point of the November 6 episode displaying a list of epithets attributed to him: “racist, fascist, xenophobic, and homophobic.” In the same vein, his detractors depict Ventura Visão as “partaking in shenanigans,” as a “puppet guy for obscure interests,” or in contradictory terms for being “too permissive” or having “dictatorial tics.” Additionally, the journalists also often assume the character criticisms in the reporting. A distinctive shared pattern consists of portraying Ventura to have a forked tongue. Whereas SIC mentions the “chameleonic rhetoric seizing every circumstance to adjust his narrative ranging from the radical extreme right to the social democracy,” Visão points out that he employs “the salami method to everyone, serving rhetoric slices adapted to pensioners, teachers, police officers, firemen, and the nostalgics of the old regime.” Pedro Coelho also signals the presumptuous attitude of “the most polemic member of parliament in the country” given that “in his head is God in heaven and him on earth” or “a Messiah born in Mem Martins (Lisbon region).” While Miguel Carvalho refers to him as a “political serial arsonist” for firing up the debate in the public sphere alongside another powerful metaphor of the “the virus of democracy.” José Lourenço rivals Ventura as the target of character criticisms. Beyond “feed-

ing hate in the social media,” Porto’s district leader is reported “to threat,” and to resort to “bullies to intimidate” whoever comes in his way. More concretely, SIC reproduces an audio recording of him threatening a fellow party colleague to dare to show up in Porto. And his right-hand man in Porto, Pedro Moura, was also tapped by a former party member with explicit life-threatening menaces (shortly posted on Facebook).

Two main topics prevail within administrative criticism: the illegalities verified at the time of the formalization of Chega and the ongoing suspicion surrounding the party financing. SIC and Visão report in tandem the over 2600 irregularities detected in the verification of signatures to officially register the party including one 8-year old, one deceased, and 250 pages with the same lettering described as “mass forgery” and being investigated by the public authorities. Quite the opposite in terms of exposing the suspicions given that the two news outlets only coincide in resorting to Ventura’s assurances of the inexistence of any “illegal financing of his party,” an unsuccessful fundraising dinner held in the North of Portugal, and the “shadows” surrounding the sponsoring of César de Paço.

After a difficult start, “all of the sudden” according to a former Chega founder, Pedro Perestrelo, the party “no longer had financial hardship”. Visão raises several possibilities for that. A former Madeira (autonomous region island of Portugal) leader who later expelled himself from the party, Miguel Tristão Teixeira, considers the proximity with César do Paço and his representative (José Lourenço) as likely to associate the party with “less clear situations” while acknowledging that “nobody has a clue about how much money gets in and how it is spent”. João Viegas describes Ventura as the “frontmen” of the “interests” of “obsessed religious leaders” with “significant financial resources,” in the December edition. Likewise, Rodrigo Freire refers to the party as a “façade,” while Samuel Martins denounces that “money rules.” Finally, Carvalho questions both the money officially spent in the general elections campaign, which got Ventura elected considering it a “bargain” and Ventura’s narrative to “end corruption, thugs and shady deals” of as boomeranging him. SIC prefers to center its coverage on verifying and critically exposing César do Paço or resuming the parallel with similar far-right countries (in Italy and France) that resort to Russian clandestine financing, which becomes a story of its own in the last episode of the series. The reporter Pedro Coelho has no doubts in connecting the “mounting evidence of illegal financing of the party” with the “obscure past” of César de Paço.

Although less often, truth criticisms also appear in the reporting. SIC tends to directly confront André Ventura, Diogo Pacheco de Amorim, and José Lourenço during the recorded interviews or discrediting their declarations in the immediate afterward. An elucidating example of that regarded the resigning of Patricia Uva due to internal struggles. He denied that a vote of honor was given to her, as Ventura had just declared to him. Coelho also challenges Ventura’s narrative about the Roma people by juxtaposing official data and the testimonies of community members. Or, he deflates Chega’s record score in the previous general elections as “merely over 300 votes and the 6th ranked party in the region”. As for Carvalho, he exposes several conflicts within Chega: that the “peace in the party is but a mirage”; that one of the Vice-presidents, Nuno Afonso, that was still illegally enrolled in his former party (PSD); Gerardo Pedro hired to work privately for the Chega soon after being dismissed from the party as a result of allegations of creating fake online profiles, or the publicized invitation for Ventura to participate in the Trump’s convention that turned out not to be so.

Lastly, there are scarce references to policy criticisms and SIC finger points Ventura’s contradicting proposals surrounding the pandemics on its April 6 reporting when swinging between “closing the borders” and “easing up the restrictions that are killing the economy and the families”, should suffice to illustrate it.

Conclusion

The communication-centered approach to populism has traditionally focused on the media platforming populist messages and paid little attention to understanding alternative roles media play that is less, or not at all, in the interest of populist parties and actors. Also missing from the large body of theoretical and empirical research on the reporting of populism is the examination of investigative reporting and cross-media comparative studies. While exploring the uncharted area of the adversariness in the reporting of far-right populism, this study aims to distinguish the different kinds of criticisms featuring in the news coverage and identify which of those criticisms trace back to the initiative of media professionals. The study is also an elucidating example of the specific journalistic dynamics of the investigative reporting genre across different media types and a revealing case of a national press system (and political reality), usually overlooked in the literature.

The findings of the analysis of the Visão and SIC’s investigative reporting of the populist far-right Chega make it possible to answer the explorative research questions formulated earlier. In a nutshell, it concludes that ideology and strategy criticisms dominate the coverage to the detriment of character, administrative, and truth criticisms, with policy ones only negligibly featuring in the reporting (RQ1). Also, most of those criticisms featuring in the news coverage are journalist-initiated (RQ2) and with relevant differences across media segments in both cases, with SIC standing out. Although aware that other mechanisms may also be at play, given the space limitations, two media-related dynamics are of interest to the present discussion in helping to understand and justify the findings. To start with, the general professional code of conduct of neutral and balanced routine coverage, through resorting to sources to provide perspective and add depth to the news story (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001), needs to be balanced on this occasion with the adversarial particularities of investigative reporting (Lanosga et al., 2017; Reich, 2012; Weaver et al., 2007). Unlike the former, in which journalists often passively rely on elite officials and experts as initiators of the news and/or critical sources of the information, investigative reporting employs more active enterprise methods by the news professionals.

What is more, the reporters’ initiative goes beyond the extensive research and intensive inquiry, as a trademark of investigative reporting (de Burgh, 2008; Nord, 2007). It presupposes more independence to generate news stories and, above all, voicing criticisms in the way routine journalistic coverage does not (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001; O’Neill & O’Connor, 2008; Sigal,1973). Indeed, besides basic fact-gathering techniques and interviews with sources that routinely serve to separate facts from opinion and defend the reporting from critique (Schudson, 2001), investigative journalism is likely to rely more on the endogenous critical commentary and evaluation by the reporter (Donsbach, 1995; Lengauer et al., 2012; Semetko & Schoenbach, 2003). Unsurprisingly, this translates into a quasi-omniscient narrator’s intervention in the reporting. More concretely, it is noticeable through providing eyewitness observation details or appropriating some of the information conveyed during the fieldwork investigation. It also involves providing analysis and interpretation or and expressing their opinion. In fact, both investigative reporters confirmed this during the reconstruction interviews. Other than the “ordinary and compulsory practices of good journalism,” Miguel Carvalho admits that comprehensive and in-depth investigative reporting also makes room for “analysis, framing and interpretation” (personal communication, March 28, 2021). Pedro Coelho further justifies it by the fact that TV is a medium the investigative genre builds upon “a narrative of contradiction” that puts journalists “in a leading role as gatekeeper and a guide that conducts people towards the possible

truth in the reporting” (personal communication, May 15, 2021).

Closely related to this is the issue of credibility. Building on the usage of academics and borrowed press as conventional journalistic tools (Albæk, 2011), the journalists’ voices or words may also enhance the investigative reporting’s credibility. That is, even more, the case when senior reporters are involved with a previous reputation of airing or publishing influential news stories (Berkowitz, 2019), like Carvalho and Coelho. Aware of their enhanced power to solidify the credibility of the reporting, the investigative journalists appear throughout the reporting functioning both as framing devices of exogenous criticisms and as initiators of endogenous criticisms against the populist actors to grant “added authority and veracity to the news story” (P. Coelho, personal communication, March 28, 2021; M. Carvalho, personal communication, May 15, 2021). In sum, and notwithstanding referring to the investigative reporting of a specific newsmagazine and a tv network within the Portuguese political setting, the findings have implications for the mediatization of populism research. This study extends previous works regarding routine news coverage of populism by exposing the high adversariness of the Portuguese investigative reporting of far-right populism. It also validates the enterprise of the investigative journalists initiating the news story and taking the lead in most of the criticisms in the reporting.