1. Introduction

Since the dawn of time, art has been a fundamental element in human being's life, and it has been so for a long time before we realized it. We are aware of the earliest art forms referring to rock inscriptions found in the caves where our ancestors lived to shelter from external threats and horrible weather conditions. The caves have slowly become increasingly complex and articulated dwellings, but it has always been possible to find traces of art within them. For centuries, art has played an essential role in the life of many. According to Morris (1882), it was customary to have several paintings hanged on the walls or sculptures in different corners of the house, and for the first time, from the home of the common person, houses have become objects worthy of the attention of architects. Right after the Ruskin (1819-1900) theories on 1870 (“Life without industry is guilt, industry without art is brutality”, 1870), Morris is the first artist to understand how precarious and weak the social foundations of art had become in the centuries following the Renaissance, especially after the Industrial Revolution (“If our houses, or clothes, our household furniture and utensils are not works of art, they are either wretched makeshifts, or, what is worse, degrading shams of better things”, 1882). The starting point of Morris's doctrine is the social condition of the art of his time, posing the fundamental problem for the art of our century: "What does art matter to us, if not everyone can share it? " (Morris, 1882). Things have changed so much that now art is considered an accessory whose presence does not contribute so strongly to defining the project's character (Romanelli, 2019). The industrial revolution, offering architecture the large-scale availability of new materials, such as the iron and reinforced concrete, ends up splitting critics opinions on the link between scientific and artistic progress. What is constructively simpler, faster to execute, perhaps still more resistant and in any case obtainable with readily available and recently invented materials, is more appropriate? In short, what is more modern, is automatically more beautiful? The Modern Movement spread, believing that “the lower the level of a people, the more abundant its decorations” (Loos, 1910), also contributed to change the role of art in human habitation. Despite the great role in architecture theories, Loos (1870-1933) is one of the fathers of the most rigid and uncompromising version of Architectural Rationalism (“The house has nothing in common with art and architecture is not to be included in the arts. Only a very small part of architecture belongs to art: the tomb and the monument. Everything else that fulfils a function is to be excluded from the domain of art”, Loos 1910). Thus the social and reconstructive urgencies of the second post-war period, throughout Europe and especially in Italy, contribute to disseminating a simplified and repetitive version of the works of the Rationalism's masters, from Terragni (1904 -1943), Figini (1903 - 1984), Ponti (1891-1979), Bottoni (1903-1973). In the Italian architectural framework of second post-war, the “2% law” was enacted to try to reconnect art (or décor) and architectural domain. After 1949, the "2% law" produces some results, but often not of excellent quality: the law mentions insertion of works of art as the method to follow, which is a system that has little to do with the complex cultural interactions typical of a collaboration between different professions and aesthetic visions. It can be said about the Italian experience that a law is not enough to bring back virtuous behaviours lost because of the inevitable change of times (“If the law was submerged, this is due to the national lack of aptitude for cultural planning and the fall of these values in contemporary architecture. I have never seen an architect conceive a decorative arrangement for a public building in collaboration with an artist. In recent decades, the 'application' of a decorative piece has come to prevail, perhaps of quality but without any familiarity with the architectural form's space-time. In short, everything is resolved in an object to be hung, superimposed, attached, but not to be created in its autonomy”, Collina, 2009). In the yacht design field, art is too little present on board, except for some projects dating back to the beginning of the last century and a few projects displayed in the case studies analysis. Since yacht design can be considered a category of architecture, it is fundamental to analyze the relationship between these two worlds according to some of the past years' most relevant points of view. The relationship between architecture and naval design has attracted the most influential architects of the last century. Le Corbusier (1887-1965) travelled on foot to Italy and Europe's cities, and he was an enthusiastic user of trains, ships, planes, and airships. However, it was the first steamers that struck him more than anything else. Barthes (1956) helps to explain this fact: "If we consider the boat a matter of living much more of sailing, the ship may well be a symbol for departure; it is, at a deeper level, the emblem of closure. An inclination for ships always means the joy of perfectly enclosing oneself, of having at hand the greatest possible number of objects, and having at one's disposal a finite space." Therefore, for the designer, it is a matter of dealing with an articulated system of historically represented morphological and spatial relations, in which the multiplicity of human activities, the spatial area, and the equipment present on the craft, which, if, on the one hand, continues even today to relate to a strong tradition of nautical practice, on the other hand, is called on to deal with the evolution of roles and tasks onboard, which tend to follow morphological, functional, and technological modifications in positions and equipment (Di Bucchianico & Vallicelli, 2011). From the point of view of yacht designers, several questions arise: why can we consider a house decorated with stuccoes, frescoes, marble, and precious furnishings a real work of art while we do not think the same for a yacht? Now that art starting to get on board again as it did more century ago, will anything change in the boat's concept as a product in the future? This paper is an attempt to give them an answer.

2. Framing the problem

2.1.1 The interconnection between architecture and yacht design through the XX century

There is a lack of references to the artistic field in the maritime and yachting sector in literature, so a parallelism between architecture and “floating” architecture is performed. Before entering the nautical field and answer this question, it is necessary to outline how the bonds between the two Latin concepts of utilitas (functionality) and venustas (aesthetic) were broken during the last centuries. According to Vitruvio (80 b.C. - 15 a.C.) the first real essayist in the architectural field, all buildings must meet the requirements of solidity, usefulness, and beauty: aesthetic research, different according to the environmental and cultural context, has undergone enormous changes, passing from periods in which beauty was something certain to more recent periods in which beauty has become relative. In the most ancient times, Vitruvio hopes that the work’s appearance was pleasant for “the harmonious proportion of the parts.” (Vitruvio, 15 b.C). Therefore, what is considered beautiful had to respect a compositional symmetry, in addition to using a whole series of canonical elements (columns, arches, entablatures, etc.). The architectural field has faced a real crisis of values, especially in the last decades of the XX century, exemplified by the almost complete lack of art in new constructions: at the end of the 1960s, the debate around the Modern Project entered into crisis, and with it the whole notion of Modernity (“Technology becomes predominant: since the end of the 60', science has been placed more and more at the service of itself. The technique is an extraordinary tool that offers great possibilities, but by definition, has no purpose. It is without an end in itself. This absence of aims has prevailed. In the last forty years, a significant strand of architecture has concentrated on creating something that was the symbol of the idea of technology as the pre-eminent force of modernity” Gregotti, 2008). This crisis’s scale is even more evident concerning the statement according to which architecture meant to “built poetically” (Gregotti, 2008), in contrast with a law enacted in Italy during the post-war period which forced art presence in new buildings without any successes. Moreover, the designer’s crisis towards the end of the second millennium is represented by Aldo Rossi’s death in 1997: he closes the architectural experience based on the strength of formal language (Leoni, 2008). Thus, in his last work for the reconstruction of the Teatro La Fenice, the figure of the Architect-Artist (Leoni, 2008). Despite the modern movement’s concealed crisis, it is possible to highlight a series of positive examples that display the contamination of the architecture with some nautical taste and design: starting from the 1900s, many architects looked to the nautical field to draw inspiration for their projects. In the USA, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) celebrates “the age of steel,” stating that “the steamers will take the place that the works of art had in the previous history,” (1901). Simultaneously, in Germany Hermann Muthesius (1861-1927) invites to look at “railway stations, exhibition halls, decks, steamers, etc. We are faced with a severe and almost scientific Sachlichkeit, unrelated to any useless decoration and with exclusively dictated forms by the purpose for which they are to serve. The buildings and the objects of use, created at the time second this principle, they showed indeed a harmonious elegance, born from functionality and essentiality,” (1902). Furthermore, also some artist like Hermann Obrist (1862-1927) speaks of the steamers concerning the “beauty in the mighty curve of their colossal but balanced contours (...) of their marvelous usefulness, of their elegance, smoothness, and splendor” (Obrist, 1968). In addition to theoretical references displayed, there is no shortage of realized projects that highlight the close relationship between the world of architecture and that of floating architecture. The Unité d'Habitation (1952) in Marseille, which transverse section is much more similar to one of steamers than of a building, is a perfect example of “machine à habiter” (Le Corbusier, 1923): this huge volume, supported by the pillars, seem to float, its horizontal windows look like ship cabin windows, and the rood garden ventilation sculptures look like chimneys of a steamer’s upper deck (Rossi, 2007). Another example is the Maison en bord de mer (1927) designed by Eileen Gray (1878-1976) in Cap Martin Roquebrune: life on board references is so strong that the designer’s style has been dubbed “transatlantic style”. Solutions that answer life experience problems in environments cramped as a ship’s cabin seem to be the most relevant contribution of furniture by Eileen Gray. The theme of sea travel is an element whose allusion is also frequent in a symbolic manner, as can be deduced from the nautical chart hanging on the main hall wall with the phrase that has it surrender famous: “l’invitation au voyage”.

2.1.2 The role of art onboard in the last century

Most of the literature about art onboard mentions the Italian steamships designed during the first decades of the last century as the highest example of art and yachting’s coexistence, highlighting a deep crisis in categorizing the most recent projects. In addition to the practical aspects of passengers and commercial traffic, after World War I, the steamers’ concepts rotate around a high nationalistic content to express its industrial potential (Crusvar, 2004). Simultaneously, the interiors became “showcase” of the best national manufactures, a traveling alternative to the pavilions set up in the large universal exhibitions. In the period between the two World Wars, the golden age of the so-called floating cities, “the ship’s meaning began to change. The desire to sail and the ship’s concept as a status symbol increased the architectural culture’s interest in vessels as industrial products, with symbolic and ritual representations: the great dream of the design was not only to reach the sea but to cross it, recognizing in the journey a way to acquire one’s own identity in front of the rest of the world” (Piccione, 2001). Some architects decided to be egalitarian and open society spokesmen, trusting in the machine and technology to project into the future the great cultural and artistic past of Italy and the Mediterranean. Among these, it is possible to include famous designers such as Gustavo Pulitzer Finali (1887-1967), the Coppede brothers, and Gio Ponti. All of them made a fundamental contribution to the development of naval design and to a new paradigm construction at the base of which art was present at the opening of building material. The last decades' projects appear uncertain in their typological characterization as they lack that symbolic dimension the architectural culture of the previous decades has instead restored to the project. Moreover, the nautical field has always been characterized by strong stylistic immobility (Barthes, 1956). As the ships are the emblem of closure, the stylistic evolution has always been a prolonged and challenging process bearing fruit in recent years. As already happening in the absolute luxury real estate (Deloitte report 2019 about Art Finance), the link between art and boating should be a close relationship based on the convergence of buyers and aesthetic objectives. Going back in the years, we can get feedback on how the coexisting of masterpieces of art and yachting has always been very strong. The first floating art galleries have been the cruise ships: the best-known ship, the Titanic, in addition to the elegant furnishings in the Georgian and Louis XIV-style, boasted an extensive collection of greats paintings that embellished stairways and halls dance. To corroborate the thesis according to which art and yachting are two linked universes, the overlap of buyers from the two sectors is around 75% and is bound to grow in the future (Deloitte report 2019 about Art Finance).

3. Methodology

With the aim of increasing knowledge about art's presence in the yacht design field, the research methodology is based on literature review and case studies analysis. Three main data gathering methods were performed: desk research, yacht designers’ interviews, and infield observation. The study first conducted a literature review based on historiographical research that considers the main theories about yacht design aesthetic evolution through the last century. This activity encompassed a review of approaches from both sociologists and architecture's historians such as Pevsner (1936), Barthes (1957), and world-famous architects such as Ponti (1931), and Gregotti (2008). Then, a timeline that highlights the steps of naval design put in order the findings, from the first steamships realized by Coppedè brothers to the memorable ones of Gio Ponti, passing through the experience of Gustavo Pulitzer Finali. The results of these first studies framed state of the art and research inquiries, summarized in the second chapter of this paper. Second, case studies were selected based on a common thread: the attempt to bring art closer to shipyards values, passing through the yacht design itself or the organization of promotional events. The analysis was conducted from successful and unsuccessful projects (as described by the research documentation or by designers’ interview) to have a complete strategy overview and to highlight the different approaches adopted by several shipyards to achieve the same goal. Projects where art only appears just as decor were analysed to outline when the relation between art and architecture broke during the last centuries. According to the two Latin concepts of utilitas (functionality) and venustas (aesthetic), the references found have been divided into clusters, based on the relationship between art and yacht: (a) an intrinsic link between art and design, or (b) art just as a decorative accessory added almost at the end of the project. While it is easy to explain a case study of a project in which art is used just for its decorative purpose, it cannot be said the same for the projects where art plays a central role in the concept definition. To frame in the best way this category of project, yacht designers’ interviews have been interviewed. The last step for collecting case studies is the infield observation: cultural events, periodic shipyards and boat shows visits help bring the research one step closer to reliable results. Thanks to the infield observation, it has been possible also to highlight another cluster (c) that refers to some recent shipyard attitude: the increasing participation in events and fairs closer to the field of art than yachting.

4. Findings

The case studies analysis results into three different categories of relationship between art and design in the project analyzed or in the shipyard behavior: (a) art as an accessory, (b) art as a building material, (c) art field related events. Category a includes projects in which art appears onboard just as a decorative accessory (for example, a paint hanged on a bulkhead), with no relation between the artwork and the surrounding environment. On the contrary, category b comprehends yacht design projects in which art onboard is considered as a building material, and in which for that reason, it is an organic part of the project. Categories c refers more to shipyard attitude towards art than yacht design projects. More specifically, in this category are included case studies of events promoted by shipyards or in which they have participated, in which art plays a central role, such as contemporary art fairs, design weeks, or private events. Furthermore, in this category find also space a series of events not directly related to the art field, which, however, can expand the catchment area of shipyard through the everting of brand's values.

4.1.1 (a) Art as an accessory

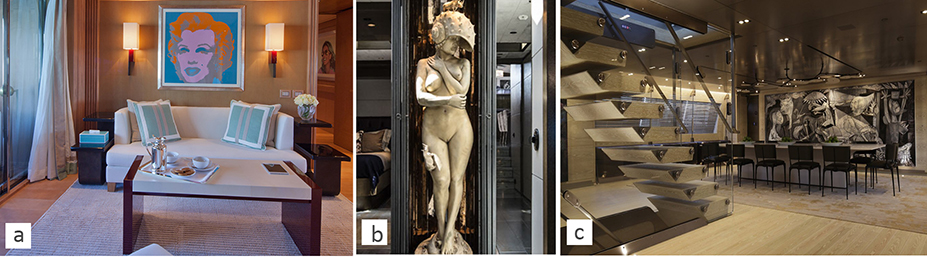

There are plenty of cases in which owners put artworks onboard after the yacht's building and delivery. After a broader study, the present research includes as case studies the presence of iconic masterpieces on board as part of the owner's private artworks collection. Probably the most relevant example of this approach it is the one of Leonardo Da Vinci's Salvator Mundi (1490-1500), the most expensive painting ever sold at a public auction (Christie's, New York, November 15th 2017). According to a report by Kenny Schachter published on Artnet on June 10th, 2018, Prince Badr has been a stand-in bidder for his close ally Saudi Arabian crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, and the painting has been stored on bin Salman's luxury yacht, Serene (2011),: built by Italian shipyard Fincantieri with interior design by Reymond Langton Design. At delivery, she was one of the ten largest yachts in the world with an overall length of 133.9 m and a beam of 18.5 m. The same happens for Seasense (2017), the 67 m superyacht built by the Benetti Italian shipyard in 2017: the owner brings onboard some artworks from his private collection. Saffron (2015) painting of Valerie Belin (1964) was chosen for decorating the master's cabin bulkheads, while all around the decks is it possible to found artworks by Arnaldo Pomodoro (1926), or by the visual artistist Daniel Steegmann Mangrané (1977). Also the main deck salon of Chopi Chopi (2014), a motor yacht built by CRN shipyard, hots a statue of the Colombian artists Fernando Botero (1932), and paintings by Andy Warhol (1928-1987), Georges Braque (1882-1963), and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). Lucio Gianfranco Zappettini's (1939) artworks can be found in the owner's cabin of the SL 100 by Sanlorenzo yacht, while Massimiliano Luchetti's (1975) painting in the SD 126 owner's cabin. Sailing yachts are also subject to this phenomenon, albeit to a lesser extent. One of the most recent examples is represented by Pink Gin (2017) sailing yacht, a 53 m carbon fiber sloop built by Baltic yacht: the owner's suite has an artwork by Cuban artist Roberto Diago (1971), while in the lower deck foyer, it is possible to see a statue by Roberto Fabelo (1951). The same happens onboard of Perini Navi 70 m ketch Sybaris launched in 2016. Are dozen yachts like these, which host a part of the owner's private artworks collection and, in most cases, it is possible to highlight the lack of relation between the project itself and the artwork added at-post. As result, despite the different artwork types, all yachts share a common feature: the almost complete absence of a thread between space’s design and artworks present in it. Here the art onboard is only an accessory and does not contribute to intrinsically connote the project.

4.1.2 (b) Art as a building material

Into this case studies' category fall yachts in which art plays an essential primary role, even if it is a rare project approach. Here the link between art and yacht design is so close that it is possible to refer to these projects as gesamtkunstwer (Trahndorff, 1827), a total artwork: works of art are inseparable from architectural spaces design as if, in turn, the art itself is one of the materials with which the ship is built. The number of projects included in this category is still tiny today. This fact is due to an intrinsic difficulty of making art and design coexist harmoniously without one dominating the other. Furthermore, this kind of project cannot be disregarded from the owner's strong will and his great passion for art. One of the projects that best embodies these features is Guilty, a motor yacht designed by Studioporfiri in 2008, starting from a pre-existing hull built by Rizzardi Shipyard. The owner, Dakis Joannou, a Greek Cypriot industrialist, is one of the greatest contemporary art collectors (he founded the Deste Foundation of Athens). Like any self-respecting home, he wished that the "floating" one became the mirror of his passions and lifestyles. His will for this project has been no longer to surround himself but to live within art literally. To do this, he turned to Ivana Porfiri and one of the greatest contemporary artists, Jeff Koons (1955). Their work is an extraordinary object, like a real work of art that contains smaller others inside. Also, for this reason, moving away from practice, Guilty shuns the unsustainable comparison with other types of pleasure crafts. While from the outside the yacht looks like an enormous canvas by Roy Liechtenstein (1923-1997), the predominant colour in the interior is white, like a real White Cube (O'Doherty 1986), the modernist definition of hyper-technological space of the exhibition galleries: the art collection present on board, curated by Cecilia Alemanni, includes works of Martin Creed (1968), Ricci Albenda (1966) and Sarah Morris (1967). Each work of art onboard is perfectly integrated with the surrounding environment, as if at that exact point there could be nothing other than that particular artwork. Feeling (2003) neon installation by Creed, placed in the mirrored wall above the headboard in the owner's cabin, modifies the whole place atmosphere; Albenda and Morris intervene in guests' cabins, the first one with Eclipse (2008), an anamorphosis that allows the correct view of the image only from the entrance; the second with Guilty (2008) canvas, a word that offers it a cue for the boat's name. David Shrigley (1968) draws on the aft cabin wall with his deliberately elementary technique. Anish Kapoor (1954) installs in the main salon one of his famous concave circles composed of mirror plates, playing with transformation, through deformation, of the surrounding space. The stunning result has been possible because each space was designed knowing precisely which works of art would be placed onboard and where. Another great example is Sea Force One, a motor yacht of 54 m built in 2008 by the Italian shipyard Admiral and designed by Luca Dini Design and Architecture. Sea Force One is an authentic contemporary art museum with extraordinary pieces of significant impact. Are several the artworks scattered on the three decks, including sculptures, paintings, and light installations. There is a very close relationship with contemporary art on the yacht, and this is due its designer, Luca Dini. According to him, the relationship with art is an experience that enriched anyone who works within, and it is an important way of creating culture. The small number of case studies found explains both the difficulty and the grandeur of this approach. Despite this, the examples displayed in this cluster are witnesses of the power that art has in aesthetically and stylistically connoting the boat. In all these projects, art is an integral part of yacht design and integrated so well into the living spaces in the boat.

4.1.3 (c) Art field related events

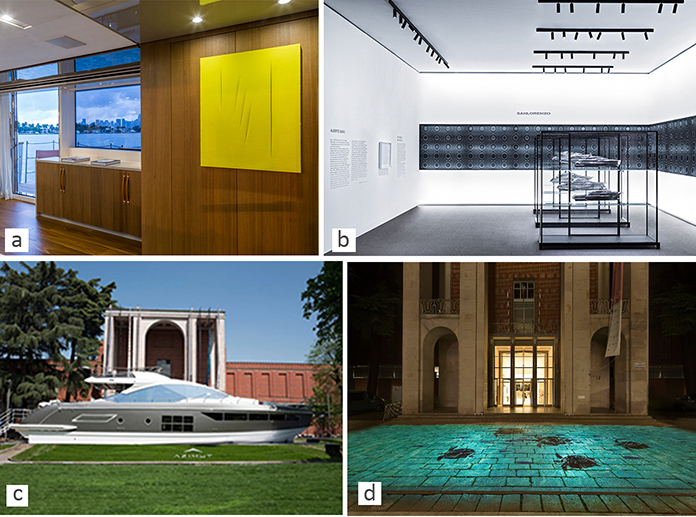

In recent years, an increasing number of shipyards are participating in events linked with the artistic field. It had never happened that shipyards had the will, regardless of the end customer, to establish a lasting relationship with the world of art. The participation of fairs and events dedicated to art and design allows shipyards to expand their user base. As already mentioned, shipowners are often art collectors and vice versa. The collaboration between shipyard and art and design fair during recent years are collected in this case studies category. Sanlorenzo Yacht, Italian shipbuilding specialized in producing luxury yachts and superyachts, from 24 to 70 meters in length, has been a forerunner of this approach. In 2016 the shipyard was admitted for the first time in Art Basel, the most significant modern and contemporary art fair on the international stage. During the edition of Art Basel Miami Beach, Tornabuoni Arte has chosen to present itself curating onboard SD112 yacht an exhibition dedicated to Monochrome Italian, one of the '900 painting movement, born in the same period of Shipyards. A significant series of important artworks belonging to the foremost exponents of this movement formed an artistic path onboard: Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Enrico Castellani (1930-2017), Alberto Burri (1915-1995), Paolo Scheggi (1940-1971), and Agostino Bonalumi (1935-2013). For the following years, Sanlorenzo presented itself at the fair with an exhibition stand, the Collector Lounge, designed by Piero Lissoni (1956): silver yachts scale models are exhibited alongside works by different artists each year. Also, the Fuorisalone di Milano, during the design week, has opened its door to shipyards: it has happened for the first time in 2017, when the Triennale di Milano hosts a suggestive video installation realized by NEO - Narrative Environments Operas - for Sanlorenzo Yacht. The ADI - Associazione per il Disegno Industriale - has recognized this initiative's success by assigning the Compasso d'Oro 2020 award for the Exhibition Design category. The following year, Azimut Yacht also participates, exhibiting the Dolce Vita 3.0 yacht in the Milan Triennale park. Another excellent example of this attitude is Peggy Guggenheim's choice to extend the partnership to its foundation to nautical field partners such as Sanlorenzo Yacht. The collaboration was sanctioned with an exhibition entitled "Migrating objects" about the journey's theme, a passion shared both by the shipyard and the world's most famous collector, Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979) herself. Even if competitors, several shipyards adopted the same strategy: using social channels to promote their closeness to the world of art. Ferretti Group chooses art as a marketing way to promote its brands and values: Riva in the movies is a project presented during Venice Film Festival 2020. Short films series made by Riva shipyard and published monthly on the official social network account highlight the relation between the shipyard and art in movies field.

Fig. 3 Selection of case studies. Caption: (a) Sanlorenzo SD112 hosts onboard Tornabuoni Arte exposition during Art Basel Miami Beach 2016; (b) Sanlorenzo Collector lounge projected by Architect Piero Lissoni for Art Basel fairs; (c) Azimut Dolce Vita 3.0 international premiere during the Milano design week in 2018; (d) Il Mare a Milano (2017), video installation by Neo for Sanlorenzo yacht, awarded with Compasso d'Oro 2020 award for the Exhibition Design category. Source: The authors archive

Also Sanlorenzo Yacht, in collaboration with the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation, presents on its Instagram account the tale From one place to another, an unexpected journey through the imaginary worlds of modern artists among the Collection: each chapter tells the story of different artists. Nowadays also exist a series of promotional events, boat shows apart, through which shipyards and yacht design studios can present themselves in relation to luxury brands. The reason for this phenomenon could be found in a common marketing strategy. Today, the design of a commercial format is more and more based on the outgrowth of brand's values and their translation into communication materials and spaces in which the end-user can move freely. For example, Montenapoleone Yacht Club is an event sponsored by the Milan Municipality that sees the top fashion brands as protagonists alongside shipyards and exclusive yacht clubs. Montenapoleone district turns, for a week per year, in a real marina: the showcases and flagship store expose scale models, photographs, installations, and videos dedicated to boats that enrich their goods offers. Another case is that of Waterfront Costa Smeralda, a temporary luxury store born in 2018 as a lounge area on the Porto Cervo shore, which hosts world-famous brands, top events, and luxury ateliers such as Bentley, BMW, De Grisogono, Deodato Arte, Dolce Gabbana, Jaguar Land Rover and many others. The latest event capable of combining nautical field to the large artistic patrimony and cultural heritage is Versilia Yachting Rendez Vouz, of which first edition held in 2017. The event in the Darsena of Viareggio would be an understatement, and precisely the variety of locations makes this event a 360 ° experience and not just a "niche" salon is also about this. It is the name of the event itself, to say it. The event finds mention in the case studies because its format has the power to out yachts from the docks and carry them (literally sometimes) towards the cities, establishing a close relationship with the territory's excellences. This last category includes all the examples of strategies adopted during the recent year from shipyards to share their values beyond the yacht produced. The number of events has grown a lot in the last few years: this indicates the ever-greater willingness of shipyards to collaborate with sectors with which the public shares, as in this case, art.

Fig. 4 Selection of case studies. Caption: (a) Panerai Milan’s flagship store hosts a yacht scale model during Montenapoleone Yacht Club 2017; (b) Montenapoleone district during Montenapoleone Yacht Club 2018; (c) International art gallery Deodato Art pop up store during Waterfront Costa Smeralda 2018; (d) Igor Mitoraj (1944-2014) artworks around the port of Viareggio during the Versilia Yachting Rendez Vouz. Source: The authors archive

4. Conclusions

The paper has described why and how art is slowly going back on board with pleasure yachts. Case studies displayed have a double purpose: on the one hand, to frame state of the art on the relationship between art and yachting, on the other, to help identify different approaches with which this relationship is outlined. It is possible to say that some case studies displayed highlight art onboard is nowadays still often considered as an accessory rather than a backbone of the project. In particular, the research aims to highlight how yacht design, concerning the artistic field, adopts two different strategies that can be considered antithetical to each other: the more prominent players, such as the strongest shipyards, are doing their utmost to communicate their closeness to the artistic field, in order to attract new customers by leveraging their passions. However, in this perspective, art turns out to be little more than a marketing tool, running the risk to transform itself into the furthest thing from its true essence, just a way to achieve a goal. In this historical era so flourishing and full of stimuli for nautical design, it is essential to remember that the concept of art onboard and the concept of a suitable yacht design project are not superimposable but only side by side. Art cannot and must not become a standard onboard because if this happened, it would be emptied of its intrinsic meaning. It must therefore be selected qualitatively and not quantitatively; unfortunately, it often happens. The other approach, put into practice not by shipyard but by few design studios, is to treat art as real building stuff, and it is an essential approach because it is above all the one we need to create the identity of the project. This approach lies the key to success for the recovery of the relationship between art and yacht design and for creating new future scenarios.

5. Future perspectives and challenges

The aim of this research is more to stimulate questions than to give them an answer. Journalist and art critic, Linda Yablonsky, speaks of three types of power in art: the first comes from money, the second from fame. The third is instead an intrinsic power of art, that is, to provoke emotions. The wish is that the only power of art continues to be solely that of provoking emotions and, therefore, if "applied" to the world of architectural and more specific nautical design, that of transforming a space into place. In recent years, the relation between the yachting field and art is embodied by works of art present on board and the shipyard attitude to make art part of the brand identity. Working in a sector still closely linked to the concept of luxury as opulence and ostentation, in order to educate, or rather, re-educate the users of new projects to the "sensitivity of beauty," it is necessary that first of all researcher and designers are trained to recognize and work not only with materials resulting from technological progress but also with intangible but no less essential materials, which are entrusted with the difficult task of instilling a soul in the project: art, among these, is the most precious one. From the point of view of art and design historians, the questions this research wants to raise are the following: will yachts continue to be seen only as of the consequences of advanced industry, or can they be considered cultural assets? In a world full of contamination and interdisciplinarity, in which everything tangible can be elevated to the state of a work of art, will it be finally the turn of the yachts? What will become of so many cutting-edge yachts once they stop sailing? Museum houses have existed for centuries. Will it happen the same for yachts?