1. Introdução

In 2016, ESAD - College of Arts and Design of Matosinhos was challenged by the pediatric Service of Pedro Hispano Hospital of Matosinhos to design new visuals for the main corridor and for one of the waiting rooms, where children, caregivers and educators spend long hours between treatments, consultations or surgeries. According to the hospital's professionals, something should be done in order to promote a better hospital atmosphere and patient stay. As several studies and worldwide projects emphasize, the commitment to human well-being, either through the search of more effective treatments or through the promotion of an emotional balance, is of crucial importance for the patients' health and also for the hospitals (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2010) [2].

Although this project did not provide what is called as a Service Design, it is still relevant to mention that a transdisciplinary team was formed in order to design a solution that includes material and immaterial components, taking into account the needs of all the parties involved.

According to Birgit Mager, "Service Design aims to ensure that service interfaces are useful, usable and desirable from the customer's point of view, and effective, efficient and distinct from the supplier's point of view” (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2010, p.31) [2]. Mager points out three relevant components for Service Design: the service architecture (the functional, cultural and strategic organization of the service); interaction with users (behavior of service providers, human quality in interactions); and material evidence (the physical touchpoints that enable a positive experience with the service through the activation of various perceptual senses) (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2010) [2].

In 2002, Gillian King presented The Life Needs Model of Pediatric Service Delivery, “a developmental, socio-ecological model that outlines the major types of service delivery needs of children and youth with disabilities, their families, and their communities” (King et al., 2006) [3]. The lack of health service delivery models, particularly models for pediatric service delivery was clear in 2002, however, 19 years later we are still struggling to find models with such systemic and transdisciplinary approach that extends the pediatric services to its community. Moreover, published service frameworks describing how services could be delivered to promote service user’s wellness (King et al., 2017) [4] are still flourishing.

The Portuguese panorama of Service Design implementation to improve and innovate pediatric Services is scarce, as testified in the 2017 Identification of Innovative Projects in SNS Hospitals report. Although the issue is gaining greater awareness, evidence shows that the solutions already carried out in national territory tend to give partial answers to a service that has to be seen and designed as a whole. The reasons for this to happen may be justified by services assigned to health areas which are extremely complex and by factors that raise ethical issues and involve, in addition to medical assistance, a mediation of various spheres.

At an international level, there are several case studies which point towards a successful strategy by adopting an holistic and transdisciplinary approach to health care problem solving and by implementing innovation through Human Centered Design and Design Thinking (Ribeiro et al., 2014) [5]. The Adventure Series project by GE Healthcare is one of the best known. GE Healthcare Chicago worked to reverse the fear and anxiety that MRIs or Computed Tomography causes in users. The solution found by the team was to use storytelling, imagining adventures and transforming cold machines into places of joy and fantasy (Koppen, 2021) [6]. But this project also highlights a central issue that, in a previous dialogue with Pedro Hispano Hospital professionals, was also pointed out as crucial, which is: the need to “control” the fear or anxiety of children but also that of parents. As Doug Dietz mentioned: "If you got the child, you got the parent, and if you got the parent, you got the child” (Koppen, 2021) [6]. Thus, keeping parents well informed, committed and confident will make all the difference in their children's hospitalization (Gomes et al., 2015; Ribeiro et al., 2014) [7] [5]. Another example is the Healthcare Innovation Exchange (HELIX) Center project, which excels on having design researchers and hospital professionals working together, applying design methodology to find new problems, identify opportunities and innovate and prototype various solutions (Royal College of Art, 2021) [6].

Information and communication with the users are also fundamental strategies. As well as clever architectural, interior design and visual stimuli as illustrations, especially at a children's hospital, as shown by the Rotterdam Eye Hospital, Patient Experience Transformation Programme (Koppen, 2021) [7]. As the results of these projects testify, all of these procedures brought a very positive effect to all parties involved.

In addition to these examples, it is also important to mention the work done by various institutions all over the world, with the goal of ensuring the wellbeing of children in hospital, like EACH European Association for Children in Hospital, which brings together various associations involved in preserving the welfare of children before, during or after a hospital stay. Associations from 16 European countries and Japan are members of EACH. In 1993, EACH became an organization which gathered several non-governmental and non-profit associations with the purpose of ensuring the welfare of hospitalized children. This organization aims to implement the EACH Charter which sets out children’s rights in hospitals, known in Portugal as the Charter of the Hospitalized Child. EACH associations are looking to add the principles of the Charter of the Hospitalized Child in each European country's health legislation, regulations and guidance.

Taking into account all these premises and references, the goal stated for the collaborative project between Pedro Hispano Hospital and ESAD was to create a more welcoming and friendlier environment, with points of interest and distraction for both users (newborns up to 18 years old and their caregivers), and to support the storytelling actions already implemented by the service's educators, before and after children’s surgery or treatments. Taking care of children does not only require technical knowledge, but an integral action that clarifies doubts, fears and insecurities present in hospitalization.

To facilitate the creation of a positive memory of a space, a service and, at the same time, to provide moments of immersion in worlds of inspiring stories and joyful environments became the main challenge of this project.

2. Methodology

The process started with a series of visits to the Hospital's pediatrics Service and meetings with the various professionals and users. A record was made of the main needs and technical constraints were considered, namely, materials and products not authorized for hospital use. This was followed by a literature search on illustration and the influence of hospital decoration on patients’ recovery. Along with constant dialogue between ESAD work team and pediatric professionals, multiple solutions were analyzed. Among the various possibilities pointed out, the fact that the hospital had already implemented several actions that orbit medical practice was highlighted, for example, children’s illness fears are demystified through stories and play. Knowing this practice and others, it was decided to create a set of illustrations that, in some way, supported the already existing practice of storytelling, and provided moments of distraction and positive emotional experience for all the elements that inhabit the pediatric service.

3. The Illustrated Album

The illustrations chosen were created by Ana Melo, a student of the Graduate Programme in Digital Illustration and Animation at ESAD, in the 2014-2015 academic year. They were originally developed within the scope of Project III, monitored by lecturers Catarina Sobral and José Manuel Saraiva, in response to the module’s project to illustrate (and write) a picture book, also known in Portugal as a narrative album.

The strong link between text and image comes essentially from the massification that the printed book has achieved after several centuries of development since the printing of Gutenberg's bible in 1454. As buying a book became easier and cheaper, it was not only its informative or playful content that was part of the popular imagination, but also the habituation to the relationship between text and image visualization. The illustration visually elucidated the content of the text. Thus, we can understand a general idea of an umbilical relationship with the text that it refers to is one of the indispensable characteristics to understand the meaning of illustration. But the relationship between illustration and the image printing process implies a second characteristic to the notion of illustration. For centuries the illustration was thought to be printed, multiplied in books and other supports, whose copies were limited, essentially, by the investment that was made. Thus, the illustration was distinguished from other forms of visual production by its reproducibility. It acquired its definitive shape after being printed in the pre-established colors, dimensions and supports. Its purpose was not to show it as original.

However, not all illustrated books have the same characteristics when using illustration, making it possible to distinguish the textbook from the album. Shulevitz clearly distinguishes the two genres, from the Anglo-Saxon designation of story book or picture book:

To create a good picture book or story book, you must understand how the two differ in concept. A story book tells a story with words. Although the pictures amplify it, the story can be understood without them. The pictures have an auxiliary role, because the words themselves contain images. In contrast, a true picture book tells a story mainly or entirely with pictures. When words are used, they have an auxiliary role. (...)

The difference between a story book and a picture book, however, is far more than a matter of degree, of the amount of words or pictures - it is a difference of concept. (Shulevitz, 1997, p. 15) [9]

Thus, we can use the term child picture book, more generalized, to cover the vast majority of books for children that contain illustrations. It only implies their presence accompanying a text of variable length, but which is always the only driver of the narrative. However, in the illustrated album, the role of the image is enriched: the illustration can also support the narrative.

The expression illustrated album comes from the Anglo-Saxon expression of picture book, which has its origin in 19th century England and is a development of the storybook for children, which tells a story with words. In these, the images could accompany the development of the written text performing several functions: to make the comprehension of the text more accessible, to be mere visual translations of the textual information or to add elements to the narrative, enriching it. However, the illustrations are always contained in the words, not being thematically individualized, being, therefore, considered illustrated text books.

In the illustrated album, the illustration and the text function as a pair in which each language has at least the same importance in the conduct of the narrative. There are, however, many examples where the illustration can only support this function.

Thus, in its broadest definition, an illustrated album is like a book in which the collaboration between text and illustration is responsible for telling the story contained therein. Its specificity

lies in the intersemiotic relationship between the two components, verbal and pictorial. This relationship implies a fundamental difference because the narrative advance is not defined only by the text or written language.

In this way, we can understand one of the reference definitions of narrative album, introduced by Bader (1976), cited by Arizpe and Styles (2003):

A picture book is text, illustrations, total design; an item of manufacture and a commercial product; the social, cultural, historical document; and foremost an experience for a child. As an art form it hinges on the interdependence of pictures and words, on the simultaneous display of two facing pages, and on the drama of the turning page. (Arizpe & Styles, 2003, p.19) [10]

However, it is necessary to define objectively what characterizes an illustration suitable for children. The conclusions that can contribute to a clarification of this purpose come from several studies on the theme of the illustrated album. Some of the more recent ones substantially value the interpretation of the reaction of small readers to the illustrations, influenced by models of responses established by many authors.

Despite the growing interest in the illustration of the illustrated album, it is difficult to find absolute answers. Many of the studies do not even have definitive conclusions. As Salisbury and Styles state:

The stylistic suitability of visual texts for children is an equally subjective and contentious matter. Many publishers and commentators express views about the suitability or otherwise of artworks for children, yet there is no definitive research that can tell us what kind of imagery is most appealing or communicative to the young eye. The perceived wisdom is that bright, primary colors are most effective for the very young. The difficulty is that children of traditional picture book age tend not to have the language skills to express in words what they are receiving from an image. They can also be suggestible and prone to saying what they imagine adults want to hear. So, even with the best designed research projects, the world that children are experiencing will inevitably remain something of a mystery to us. As adults we make decisions on their behalf, even though we may struggle to retain the magical ability to read pictures that appears to come so naturally to the young. (Salisbury & Styles, 2012, p.113) [11]

Despite this difficulty, it is possible to find a general idea of clarity as being associated with illustration for children. It is Shulevitz (1997) [9] who defends these characteristics as being fundamental for the adequacy of the illustration of narrative albums for children: the need to be pictorially clear in order to be readable. Contrarily, in their studies, Arizpe & Styles (2003) [10] were fundamentally concerned with the children’s most elaborate opinions and their reactions, both to the stories - the verbal communication and their drawings -, and to the relationship of the illustrations with their respective history. Students were asked questions about the books, allowing them to see and reexamine the illustrations. To enable the children to understand the story’s development, relating it to the illustrations, the story was retold several times.

Their conclusions have been widely disseminated and support current research that defends that for children to read narrative albums can be an act as complex as reading words. With the guidance of educators or teachers, children will be able to develop visual literacy skills and strategies that will help them improve their ability to approach reading in a multimodal way through reading illustrated albums. It was also found that they improve the development of cognitive thinking skills and that, when revisiting books, illustrations were more recorded in memory than words [10].

In this way, the book, and its textual and visual informative content have mainly a formative importance for the child. Regarding textual language, Bettelheim (1975) [12] is clear in the essential role they play in the development of the child's life:

(...) I found myself face to face with the problem of deducing which experiences in a child's life were more appropriate to promote his ability to find meaning in life; to endow life in general with greater meaning. Regarding this task, nothing is more important than the impact of parents and caregivers; next in importance, comes our cultural heritage, when passed on to the child in a correct way. When children are young, it is the literature that best contains this information. (Bettelheim, 1975, 1999, p. 10) [12].

Although Bettelheim's statement was made in the mid-seventies of the 20th century, it has not lost its relevance. Literature has, since then, divided this function with other media, such as animated stories or animes on television series, or with the illustrated album. In the latter, as we saw earlier, when dividing or replacing the role of the text, the illustration also performs many of the cultural functions that were associated exclusively with it.

Thus, the reading of a book is more dynamic, not limited to decoding a text but implying the children's ability to understand what has been read and creating an opinion.

In summary, the illustrated picture book is a particular type of book, where illustration takes on special relevance in the development of the narrative, which is not exclusively dependent on the text. Its specificity resides in the relationship that verbal and pictorial components establish and that, in an articulated and complementary relationship, produce meaning.

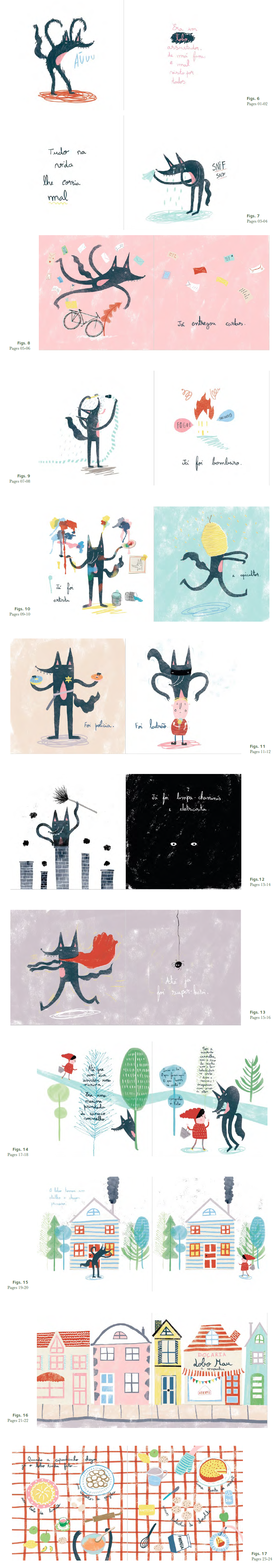

Thus, if we see illustration as starting with an idea in the illustrated picture book this idea is usually formed according to the text that accompanies it (with the exception, of course, of silent books, books without words). It was in this context that Ana Melo developed the picture book “Lobo Mau”, with text and illustrations of her own (fig. 1). The technique used was digital painting in Photoshop (bitmapped images), in a square format, with a core of 24 illustrated pages, to which were added the guards, cover page, cover and back cover. Thus, in total, the book consists of thirty two pages.

The narrative presents the daily life of a (bad) wolf and develops from a text of short sentences to an illustration of a full page or double page. So, right on the first double page, on the left, we come across a wolf, with its arms raised, as if frightening the reader, with the bristly fur and protruding sharp teeth from which comes a howl recorded verbatim by the word “Áuuu”. This illustration corresponds to the initial phrase “It was a wolf, scary, of bad reputation and badly seen by everyone”, on the right page. This double page introduces us to the fundamental characteristics of the text / image counterpoint game that will enrich the entire book. Thus, if the sentence immediately takes us back to the traditional tales of authors like Andersen or the Grimm Brothers, it also anticipates the possibility of a frightening and hideous figure. However, the illustration shows us a wolf with fragile arms and legs, like hoses in motion and a relatively childlike face expression, as if trying hard to be scary, something that clearly it is not. This irony between what the phrases suggest and the illustrations show, repeats, intensifies and takes on new forms throughout the book.

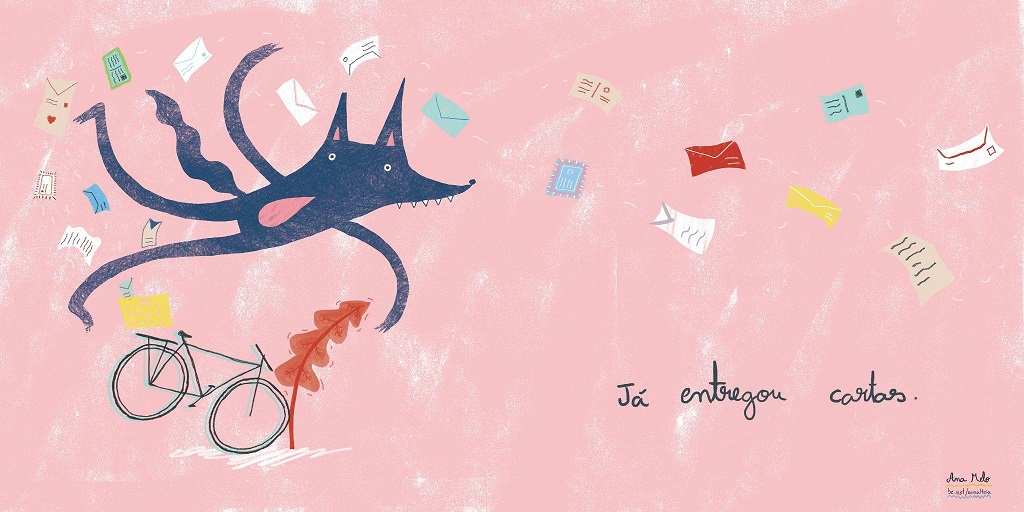

Thus, it is possible to find different categories of combinations between text and illustration, using in this example the combinations proposed by Scott McCloud (1993) [13]. Right on the second double page, it is possible to find a redundant occurrence between text and image, which sends the same message, the phrase "everything in life went wrong for him" and there is an image of the wolf weeping over his misfortune. On the third double page we can find an additive combination, the one most used by Ana Melo, in which the text amplifies or emphasizes the message of the drawing and vice versa, the phrase “Already delivered letters.'' It is accompanied by an illustration in which the wolf rides a bicycle and bumps into a tree, leaving the letters fluttering in the wind (fig. 2).

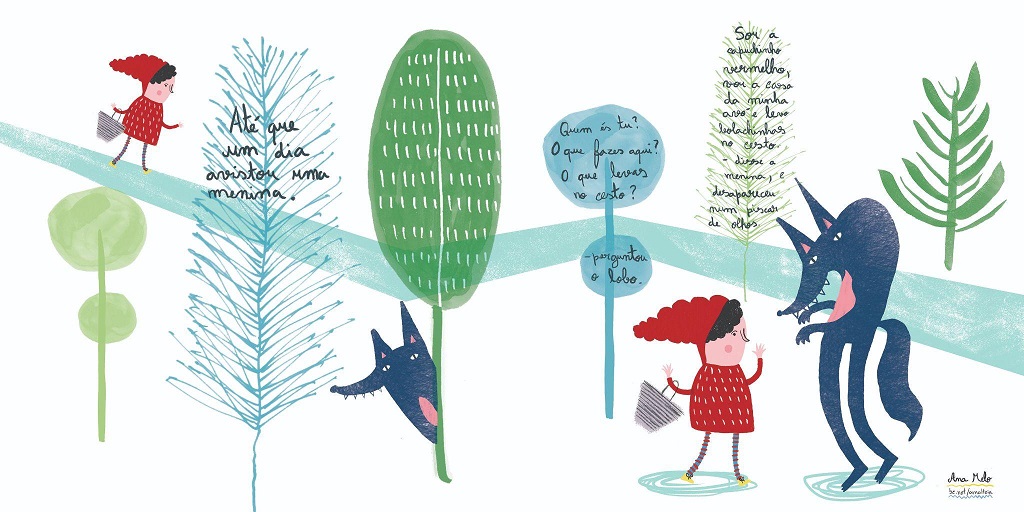

We also found a combination based on a self-sufficient text, in which the images are limited to a literal function, on the tenth double page, to the text “Until one day it saw a girl. It was a gifted girl in a red coat”, accompanied by an illustration of the wolf watching the girl in the red coat as she walks. This illustration also includes an assembly practice: the text is treated as an integral part of the image when inscribed in the profile of the central tree (fig. 3). These examples are also demonstrative of the most common category found in the relationship between the two languages on the album, that of the interdependence of text and drawing, which combine their forces to convey an idea that neither of them would be able to convey alone. In this way, we can see the exciting dynamics that the reader can find in understanding this book. But this is not a book for all types of readers. The small presence of the text and the childlike character of the colorful illustrations make it a tool of particular interest to stimulate the imagination of pre-readers and first readers. In other words, children between 2 and 8 years of age, not being restricted, however, to this age group.

3.1. Implementation in Hospital Environment

The book was later adapted to Pedro Hispano’s Hospital collaborative project, starting from the exhibition of its illustrations and corresponding phrases, in an adaptation made in several pvc panels, arranged on the walls of the corridor and in one of the rooms of the pediatrics service. But, when exhibited in the hospital corridor, have not some of its original qualities been lost? We do not believe so. On the one hand, what was exposed was the double pages of the book, allowing us to maintain the individual meaning of each one. On the other hand, its arrangement follows the original chronological order, depending on the number of pages. Thus, at the beginning of the corridor, the first double page is shown, followed by the rest in the numerical sequence of the book. However, there is a possibility that patients will start viewing the book from any point in the corridor. As we have already seen in the examples we have presented, many of the images work in the confrontation of ideas between the text and the image, a confrontation that is self-explanatory in the observation of each exposed double page. Thus, each particular image is perceived according to an analysis of its elements of characterization of the characters, scale, framing, technique, modeling, details, props, space and main and secondary actions. However, when the spectator continues to the next image, he is faced with characteristics such as the repetition of the characters that create a narrative link between the new illustration exposed and the previous one. In this way, new dynamics arise associated with the observation of images in sequence, such as questions of rhythm (expectation/ surprise), speed, assembly and movement.

Showing all the double pages, at first, works as an invitation to appreciate the others, instead of segmenting their appreciation. Thus, Ana Melo's original picture book becomes an experience of fruition simultaneously with individual illustration and illustration in narrative sequence.

These illustrations’ selection also took into account the reasoning of Mergulhão (inFerreira, 2013) [14] on how illustration should be "an imagery and pictorial sphere that will be all the richer and meaningful to the child if it diverts from the stereotype and the laws of conventionality". The illustrations from the book “Lobo Mau” by Ana Melo which were selected and put on the walls of the pediatric ward offer novelty, creativity and surprise, although seemingly reproducing stereotypes associated with fear, such as the wolf. These illustrations contribute to the children’s development of interpretation and communication skills and to enable emotional experiences, as well as positive memories of the ward and the hospital. The work on the walls draws attention to the fact that promoting a positive atmosphere in the pediatric ward is paramount (fig. 4 and 5).

Walking through this more humane space, full of colors and figures, which used to be bare and served only the purpose of connecting rooms, is a stimulating experience for the child who can now wander through it, helping them to escape their illness for a short while. These illustrations, that now reside in the big walls of the main corridor of the Pedro Hispano Hospital pediatric ward, have an attractive power, not only for their aesthetic aspect but also for the presence of verbal and visual discourse, a combination that gives enjoyment to children who have not yet mastered the codes of verbal language and by children who are beginners and/or fluent readers.

4. Conclusion

Hospitalization changes the lives of children and their families, children are away from their friends and school environment. At the hospital, they come into contact with other people and face different habits and routines, such as undergoing medical examinations, taking medication, among others. Throughout the research, we have acknowledged that the issue of pediatric hospitalization has been much studied over the years, mainly regarding the inclusion of fun and pedagogical activities in pediatric services.

In Portugal, the Instituto de Apoio à Criança (IAC), which in 1989 developed an area with the purpose of making Child Care Services more humane, has among its goals the one of promoting the dissemination and implementation of the Charter of the Hospitalized Child. In this charter, article 4 states: "(...) to reduce pain and physical and emotional aggression on the child, preventive measures should be taken - making available games and recreational activities appropriate to the child's condition and development" (European Association for Children in Hospital, 2009) [15].

Mendonça, M. (2015), reinforces this position when citing Castro (2010) "Playful activities during hospitalisation promote mood improvement, favour distraction, reduce anxiety and crying, increase appetite and improve treatment compliance, minimise pain, and function as a therapeutic tool in paediatric health care"[16].

According to the same author, children's mental representation in relation to hospitals can, therefore, be transformed into positive experiences, memories and feelings. The success of hospitalization and the therapeutic work of hospitalized children can be enhanced by the existence of transdisciplinary work teams - doctors, nurses, technicians and early childhood educators - by the presence of the family but also by the design of welcoming environments. Like nutrition, health, housing and education, playing is a basic need for children. Aware of the importance of communicating emotions and minimizing the impact of stress factors associated with the experience of the disease and hospitalization in the pediatric wards of hospitals, several recreational activities should be promoted.

An example of this effort to redesign the spaces and social rooms for sick children was the action promoted by Hospital Pedro Hispano and ESAD in a collaborative project that, through the exhibition of a set of illustrations, sought to create, in the pediatric ward, a playful and pedagogical moment for patients and caregivers. Moreover it seeked to be a significant resource in the recovery of these patients, working as an incentive to dream and imagination, providing other forms of perception of the world and the situation that patients are currently experiencing.

Although Bettelheim emphasizes the idea that illustrations enable children to enrich their imagination, develop their cognitive level, know their emotions and deal with their fears and anxieties (Martins, 2016) [17] the difficulty in assessing the actual results of this action is one of its major limitations. While, on the one hand the action was based on specific literature and the different participants in the process first impression was extremely positive, on the other hand the short time elapsed since the finished work, as well as the increasingly limited space, due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, did not allow an objective assessment of its medium/long-term effects on the quality of the space used by patients and family members. Even so, this limitation is considered an opportunity for future work. An opportunity to develop an integrated project, such as temporary illustration exhibitions, combining image and text, accessible to a greater number of children of different age groups and involving more and other hospital areas. Allowing to share playful moments with a greater community, not being limited to specific, closed spaces, and, due to their rotation, give rise to dynamics of curiosity and enthusiasm. In parallel, illustrations and stories should be developed using more specific scenarios, such as the ones children experience during hospitalization and treatment for their illnesses. The dialogue and interpretation resulting from the children - illustration - team - space dynamic is promoted, enabling children to identify with the situations portrayed, exploring and sharing their emotions and anxieties, transforming the context into cathartic and therapeutic moments.

Thus, the partnership created between ESAD and Pedro Hispano Hospital has and it keeps on having as its main goal the improvement of hospitalized children's well-being and, consequently, a better hospitalization experience. This goal is based on the premise that hospitalized children's comfort increases their confidence and enables them to ask questions and express feelings and fears.