Introduction

Our focus in this article is to describe the experience of travel mediated by mobile devices in the autonomous district of Buenos Aires, Argentina, and to identify the particularities of the usage of mobile devices1 by inhabitants. We argue for the multidimen sional aspect that characterizes the use of mobile device applications to aid inhabitants’ commuting in the city of Buenos Aires. In this sense, we describe moments in which the specificities and daily needs of inhabitants’ journey mediated by mobile transportation device applications are intertwined with their life stories.

Theoretically, our work is inspired by investigations that articulate the new mobilities paradigm in social sciences (Hannam et al., 2006; Sheller & Urry, 2006; Urry et al., 2006) and in cultural studies (Goggin, 2012; Morley, 2017; Ozkul, 2015; Ozkul & Gauntett, 2014; Wiley & Packer, 2010; Wilken & Goggin, 2012). From this perspective, com munication takes place on the move and in relation to other disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, geography, and others, addressing issues related to communication, mobility, transportation, and technologies.

In this work, we do not intend to describe the potential for developing urban mobility through the use of apps. We seek elements to understand how this process is part of people’s daily lives and, ultimately, to what extent it contributes to social inclusion, revealing the social aspects that are at stake. Our hypothesis suggests that a closer look at selected parts of the inhabitants’ routines would provide qualitative data that would reveal and characterize the points of connection and disconnection between the mobility and communication structures put in place in the city and the needs and desires experi enced by the inhabitants.

Therefore, from this broader problematic we focused on two primary questions for this work:

How are these applications used by public transport users in Buenos Aires?

How does the use of the applications by the inhabitants relate to their life experiences?

From these questions, we proposed the two objectives below:

Identify the specificities of the urban mobility experience of inhabitants who use transportation apps to move around the city of Buenos Aires.

Describe the specificities of daily urban mobility in Buenos Aires taking into account the social, economic and cultural aspects of the inhabitants’ experience

The theoretical proposal to address communication on the move had its methodological implications. In this sense, the interviews with the participants took place while they were moving from one place to another in the city. In this research we followed nine inhabitants who used transport applications to assist their displacements around the city, from the first event of their days, to the last one. As we accompanied them through the city, we conducted interviews and recorded videos from their perspective through glasses with a hidden video camera.

Communication and Mobility: A Theoretical Diagram to Understand Mobile-Guided Travel Experiences

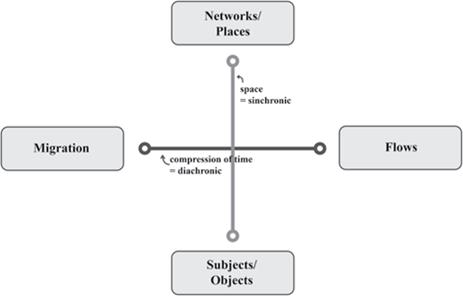

As the research developed, some notions emerged as key to understanding the relationship between communication and mobility through the experience of the participants. Questions about migration, flows, networks, places, subjects, and objects emerged from participants’ stories about their mobility experiences. Thus, the connection we established between these concepts was made through elements we found in the fieldwork. In the same way that the theoretical research provided us an understanding of the historical meaning of these terms, the field research showed us aspects of social context and practices.

Figure 1 illustrates the correlation we have established among these concepts. It shows how we viewed the phenomenon and helped us to systematize the analysis and describe the processes under study. The diagram we drew is placed on two axes: a horizontal one representing time compression and a vertical one representing space. The time compression axis associates migrations with flows, while the space axis simultaneously connects networks and places with subjects and objects. The space axis works like a frame that moves along the axis of time compression, connecting the past with the present and the slowness of migration with the high speed of contemporary flows.

Credits. Lucas Durr Missau

Figure 1: Diagram of Concepts for Interpreting Movement Mediated by Mobile Devices

With this in mind, we are thinking about mobility and communication beyond our everyday life, beyond the concrete aspects of the routine of leaving and arriving at a place. We seek to describe how these moments of daily displacement also connect with the past stories of the inhabitants of Buenos Aires. Means of transport and, in our study, mobile devices, are technical objects in relation to which “subjects construct meanings and imaginaries and through which they reproduce habitus and ways of life” (Martins & Araujo, 2017, p. 109).

As Martins and Araujo (2017) indicate, this “not only crosses objective dimensions in the use of transport or means of displacement, but also combines memories and stories of places, relationships and life situations of the authors of the narrative, as well as people and other characters” (p. 110). Thus, we describe and reflect on subjects’ experiences that intersect with mobility, such as ethnicity, identity, gender, class, politics, work, leisure, and others.

Migration studies is an interdisciplinary field, constituted by scholars from anthropology, sociology, politics, international relations, communication, geography, history, law, psychology and languages, among many others. It is also a diverse field because, in this landscape, migration studies not only focuses on the movement of people from one country to another, but also on immobility and the processes of fixation, adaptation and integration of migrants in a foreign country.

Fortier (2014, pp. 64-65) points out that scientific research that has migration as an object of study is divided into three levels. The first level - the macro level - focuses its approach on the structures or infrastructures of migration, such as institutional practices, policies and laws that regulate the movement of migrants; their fixation and integration; and transnational movements or organizations. The second level - the meso level - is concerned with travel and communication technologies; migration and settlement strategies and conditions; political and grassroots movements; and various local, national, transnational or diaspora networks. The third - the micro level - focuses on individual and collective experiences, strategies, aspirations and family decisions regarding migration and mobility, but also deals with cultural productions and representations of migrants’ lives.

Our research focuses on the social practices of displacement mediated by mobile devices. We focus the analysis and fieldwork on the micro level, since we address everyday urban mobility - micro level - interrelated with communication and technology- meso level.

Under this approach, migration connects daily mobility with the participants’ biography. Beyond revealing the country of origin of each of the inhabitants, our approach presents the movement in a historical way, complementing the notion of flows. An important node connecting the notions of migration and flows is the social imaginary as defined by Fortier (2014): “‘imaginaries’, which shape and are shaped by regimes of practices, are deeply integrated in our everyday lives and inform our ways of seeing and understanding the world” (p. 69). Migration studies with a focus on the social imaginary address how the phenomenon develops and how it unfolds among people and its interests and desires in the mobility panorama. Among the works with this scope, Fortier (2014) identifies studies of representational character of films, books, photographs, public speeches among others; and also works that try to understand how the imaginary shapes the perception of identities and differences, of borders and limitations, of the relationship with others near or far away:

what I suggest is that adding imaginaries and affect to the conceptual toolkit of migration research within mobility studies allows us to probe into the ways in which marginal and dominant, and mobile and sedentary subjects are embroiled in the inextricability of desire and politics through complex processes of internalization, incorporation and (dis)identification. (p. 70)

Migration is also addressed from the production and reproduction of differences in the urban space. In a critical dialogue with the notion of ghetto to understand the reproduction of changes in urban space, represented by authors like Wirth (1928) and Sennett (1994/1997); and another model that studied the configuration and use of urban space, emphasizing the racial and cultural heterogeneity of segregated spaces, represented by Rodríguez and Arriagada (2004) and Portes et al. (2005), Caggiano and Segura (2014) conclude, based on an investigation of the experience of Bolivian immigrants in the Metropolitan Region of Buenos Aires, that the configuration of city spaces cannot be under stood only by the logic of the studies mentioned above. In other words, “they cannot be fully understood with a simple application of the logic of the rich city center/poor periph ery, nor according to the typical scheme of the racial ghetto” (Caggiano & Segura, 2014, p. 39). According to them, the distinction in the forms of appropriating urban spaces is made by articulating between the unequal logics of the real estate market and the social stigmatization of migrants.

If, in our approach, migration is more focused on life stories, flows are concentrated on daily commuting. Both are determined by social practice. In Martín-Barbero’s theoretical elaboration, the idea of flow is related to virtual flows of images and data, where a time and space compression occurs (Moura, 2009). In our work, we extend this notion to include the social practices of mobility. Thus, the term also addresses the sense of quality of displacement and movement, relating subjects and objects with places and networks, which seek to maximize the compression of space and time.

Other well-known social sciences theorists such as Anthony Giddens, Arjun Appadurai, Manuel Castells, Bruno Latour and Zygmunt Bauman reflect on the particularities of contemporary globalization and capitalism based on the concept of fluidity, relating it to the growth of numbers and varieties of mobility (Salazar & Jayaram, 2016, p. 3). However, flows are not only characterized by their fluidity.

One of the findings in our field research was that mobility was not fluid; the fluid- ity among subjects, objects and ideas do face resistance. This empirical finding is also present in the theoretical work of scholars in the fields of anthropology, geography and sociology (Cresswell, 2014a; Edensor, 2011; Marston et al., 2005; Smith, 1996; Tsing, 2005) which problematize the notion of fluidity.

We refer to this resistance as friction (Cresswell, 2014a; Tsing, 2005), which in this context takes on a social and cultural sense. “Friction, here, is a social and cultural phenomenon that is experienced and felt when you stop driving through a city or get stopped for questioning at an international airport” (Cresswell, 2014a, p. 108) In this sense, we point out the friction among subjects, objects and ideas in the daily performance of moving around the city of Buenos Aires, evidencing the differentiated aspect of mobility.

The notions of subjects and objects indicate the experiences of people from a relational perspective with spaces, places and objects. These categories show the interrelationship between participants and mobile devices, and expose the singularities and generalities that make up these relationships.

In turn, while moving, people establish concrete and symbolic relationships with the environment. So, places and networks are created as the routes are performed; places are the anchoring points and networks are the frames that connect these points. On the other hand, on the move, subjects and objects break from established connections with certain places and create new connections with other places.

Although we approach them together, networks and places are different concepts. Places have long been studied in sociology and geography (Cresswell, 2004, 2006, 2014b; Easthope, 2004; Gieryn, 2000; Malpas, 1999; Soja, 1989). Doreen Massey (1995) proposes a definition of place that helps us dialogue with the concept of network. She defines a place as “the location of particular sets of intersecting social relations [and] intersecting activity spaces” (Massey, 1995, p. 61). As Easthope (2004) summed up, through Massey, places can be understood as “nodal points in networks of social relations” (p. 129).

In short, places are “spaces which people have made meaningful. They are spaces to which people are connected in one way or another. This is the most straightforward and common definition of a place - a location full of meaning” (Cresswell, 2004, p. 7).12

From sociology, Gieryn (2000) contributes three other elements for defining a place: (a) geographical location; (b) material form; and (c) investment with meaning and value. Conceptually speaking, they resemble Agnew’s (2002) concepts. Both authors agree on the relevance of meaning in the constitution of a place. “A spot in the universe, with a gathering of physical stuff there, becomes a place only when it ensconces history or utopia, danger or security, identity or memory” (Gieryn, 2000, p. 465).

Inspired by the studies of Massey (1994, 1995, 2005, 2007 as cited in Jirón, 2009,

p. 176) and rethinking the concept of place applied to the logic of contemporary urban mobility, Paola Jirón (2009) defines a place as an event, one which is never complete, finalized or limited. Similar to Cresswell (2001), she understands that places are in the process of being (trans)formed. Jirón (2009) chooses the expression “mobile place making” (p. 176) to characterize the daily practices of urban mobility.

Although this notion of place is linked to the constitutive elements exposed by John Agnew (2002), Jirón’s (2009) definition places it in the context of the practices of daily mobility. For her, place is the appropriation and transformation of space, a phenomenon related to the reproduction and transformation of society in time and space. The notion of place acquires a sense of openness, one that is in constant construction and made up of repeated daily social practices. “Place is the context of the practice and the product of the practice; therefore, the relationship between places and practices, particularly those that occur daily, is extremely relevant in contemporary urban life” (Jirón, 2009, p. 177).

We think of networks as the existing virtual frames through which the connection between places and the constructed senses is possible. The physical structure of the networks is place but its essence is the meaning between one place and another. Networks are the pre-locations responsible for connections that go beyond the space-time limitations of physical mobility. Networks are the abstract structure of mobility. Sometimes they can be mental and virtual maps, social networks, instant communication through messages, videos, images, informational content, and more. Therefore, when looking at communication and mobility in the context of information and communication technologies, places and networks are analyzed together with a focus on social practices.

In a broad approach, our theoretical hypothesis suggests that communication and mobility structures shape daily travel experiences and condition lifestyles. Communication technologies, which act as mediators in this process, improve the parameters that operate in these molds. However, while the applications are designed to improve the inhabitants’ integration with transportation structures, the inhabitants’ mobility experiences are challenged by social factors that go beyond the competencies planned and implemented. Therefore, our hypothesis indicates the need for public policies that aim at inclusion based on social parameters that go beyond the competencies of the technologies in use.

In this paper, we do not intend to exhaust the concepts illustrated on Figure 1, we describe how they were perceived in the context of our research. Due to the objectives of this text, our aim is to describe experiences related to migration and flows. From the narratives of inhabitants’ experiences, we describe social processes and practices that are at stake in contexts of mediated commuting. In this context, migration and flows are articulated in the daily performance of citizenship in a foreign country and in the aspirations and desires of life that are constituents of the social imaginary.

A Methodological Approach to Mobile Communication on the Move

Approaching mobility through mobile communication studies requires methods capable of following it. Thus, we needed mobile methods to monitor the displacements and creativity to find tools capable of revealing the particularities of the object of investigation.

In order to identify the particularities of the urban mobility experience of citizens who use apps to get around the city, we performed a multi-sited ethnography (Marcus, 1995, 2011) using the shadow technique (Jirón, 2011, 2012); a method of collecting video recordings which the citizens themselves recorded by wearing eyeglasses with cameras built into them.

The participants were selected by the snowball method. Participants of an initial sample done to test the methodology (participants’ adaptation to wearing the glasses and the recording of the interviews on the move) recommended other participants. The composition of the final study group prioritized users of public transportation and who use different means of transport.

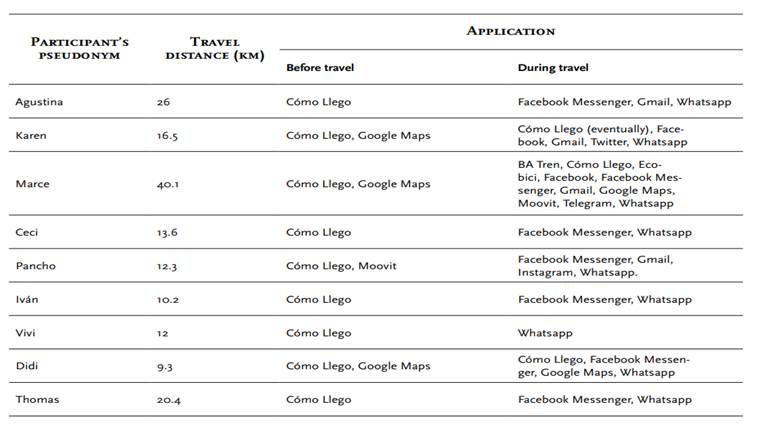

We conducted interviews on the move, as the inhabitants moved around the city, with participants who were between the ages of 22 and 34. They were native to the following Latin American countries: Argentina (five), Paraguay (two), Colombia (one) and Venezuela (one). Eight of these participants were employed and had a fixed monthly income. Only one of these participants, a musician and street artist, did not have a formal job. Their income varied between one and seven minimum wages (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-Economic Data of the Participants

Note. Argentina’s minimum wage in July 2018 was USD 602.40

The data collection instruments we used for our follow-up included interviews, mapping the citizens’ travel routes, and the videos recorded by the citizens. The interviews were based on a set of questions which citizens answered while commuting and moving around the city.

The travel routes were mapped using an application2 installed on the researcher’s phone. This application allowed for tracking locations, times and modes of travel. The videos were recorded using eyeglasses with built-in cameras which users wore during their daily trips. The inhabitants were informed about the camera and agreed to participate in the study.

We used a simple eyeglasses model for recording the videos. It is a model known on the market as “spy glasses”. We chose this model for its discretion, practicality and cost. This model of eyeglasses records videos in high resolution (HD in 1280x720p format, with a minimum illumination of 1 lux) for a duration between 50 and 70 minutes, having a total of 16 gigabytes of memory. It takes an hour to recharge the battery once it runs out.

For this research of follow-ups, we walked along nine participants for a single day. They went from their homes to their offices at work, to a bar, to a leisure activity. These movements were recorded from their own points of view. Follow-ups took place in May and June 2016 and November and December 2017.

For the purpose of this study, the participants’ routes were limited to the autonomous district of Buenos Aires. All participants lived in the federal capital, except for Thomas, who was living temporarily with his sister in the city of Berazategui, in the province of Buenos Aires. He did, however, sleep in a cultural space located close to his job a few days a week, where he got to know the owners. The most distant neighborhoods we went to were Mataderos (with Agustina), and Villa Pueyrredón and Saavedra (with Marce). We also followed research participants in the neighborhoods3 of Almagro, Barrio Chino, Bairro Norte, Belgrano, Boedo, Caballito, Centro, Colegiales, Congreso, Once, Palermo, Parque Patricios, Puerto Madero, Recoleta, Retiro, San Nicolás, San Telmo and Villa Crespo.

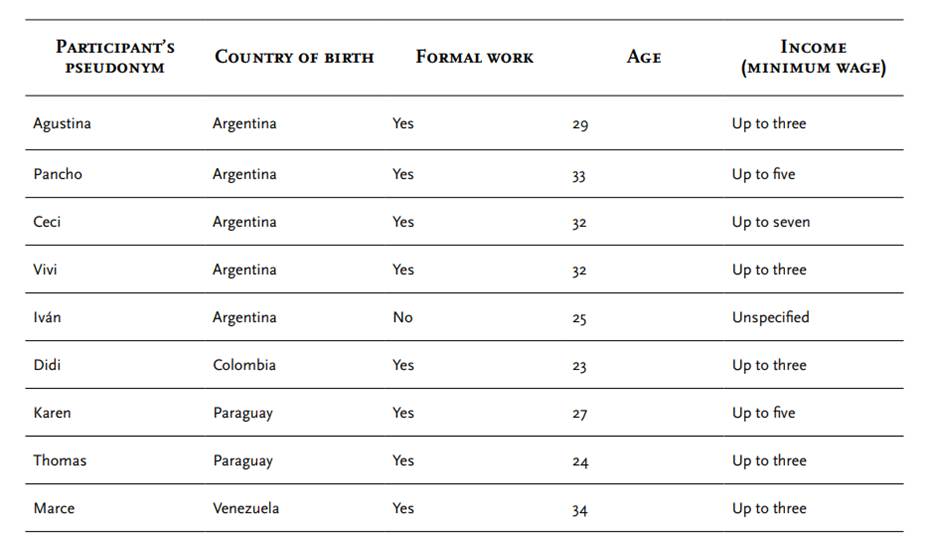

The participants moved around the city by bicycle, foot, bus, train and subway. They used the Cómo Llego, Ecobici, Moovit and Google Maps mobile phone apps4 to help them move around the city, additionally, they used social media (Facebook and Twitter), interpersonal relationship platforms (WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger) and media (we were unable to identify which) during their travels.

Therefore, the participants primarily used mobile transport applications and mobility devices in the autonomous district of Buenos Aires in the period before they travelled. During their travel period, they used email, instant messaging and social media applications, as well as relational activities.

Cómo Llego and Google Maps were the most used transport applications for the group of participants in the period before they travelled. Cómo Llego, Trem BA, Ecobici, Moovit and Google Maps were the apps reported or used during the participants’ travel period. Other applications which participants used were WhatsApp, Facebook, Facebook Messenger, Gmail, Twitter, Telegram and Instagram (Table 2).

Imagining, Adapting and Belonging: Three Processes That Articulate Migration and Flows

Here we describe how the use of transportation apps articulates the notions of migration and flows based on the narratives of participants’ life experience within the scope of this research. The specificities of the experiences that we report here are related to social, cultural, and economic aspects that we encountered while doing the interviews with the participants and accompanying them in their movements around the city. Therefore, we describe the processes in which the narratives about the experiences of migration and the daily flows of displacement are articulated with the mediation of transportation applications. However, migration experiences, daily flows and mobile-mediated travels are complex and go beyond the competencies of this work. We shall address advances of the same research in other publications.

Through the conversations with the inhabitants who participated in the research, we identified that three processes are part of their lives in the new country. Imagining a different life according to rationalized parameters, adapting to a new context of experiences and belonging to a strange and at times hostile social environment.

Four of the people who participated in the study were migrants. The predominant reason Didi, Marce and Thomas migrated to Buenos Aires were economic. In contrast, Karen had a comfortable life in her country of origin and left it to live experiences in the social, cultural and political spheres that, for her, were limited in her country of origin. According to herself, the word that best defined why she moved to Buenos Aires were diversity, which refers to social relations and artistic and political expressions.

If we identify, among the participants, that the economic aspect is the main reason for the decision to migrate, we also note that aspects related to the social imaginary are at work in the decision to move. Beyond the daily routine aspects of migration, we noted that the decision to migrate is reinforced by attempts to rationalize a social imaginary. The participants justify their decisions to leave their country of origin according to very clear parameters of comparison with the place of destination, be they regarding social, economic, cultural, and political conditions. These parameters are composed of imagined idealizations and representations of life in the new country. One of the participants, Marce, for example, used three basic criteria for choosing which country to move to:

well, one of the reasons I chose Argentina as a destination was because of its annual homicide rate. What I was looking for in a place to live was: public mobility 24 hours a day, I wanted a place with a single-digit annual homicide rate, and I wanted lower inflation (which Argentina does not have). Inflation is high in Argentina, but it is not as high as in Venezuela, which has the highest rate in the world today. The second highest is Argentina, at 27% a year. (Marce, /2017, November 29)

Another participant, Didi, was living in Bogotá, Colombia when she decided to move to Buenos Aires in search of cheaper and better education. She also questioned the average life model in her country of origin:

it is all too common in Colombia. Segregation of social classes is very bad. In Colombia, class segregation is very ugly. Here, everyone is more re- laxed... They lead a different lifestyle. I met many guys in Córdoba who said “no, I came from Buenos Aires to Córdoba because Buenos Aires is a very fast city”. For me, Buenos Aires is three times slower than Bogota. There are also not as many cultural spaces (in Bogota). In other words, people just go to work, they get home, eat, sleep and... And you see your family at the weekend. And for me, it is essential now to have a space for myself, and to go out at 11 at night and everything is still open. Buenos Aires is great. This city is great, which is why I will spend more time here. (Didi, 2017, December 13)

Imaginaries are also related to a desire for different life experiences. For Didi, accessing cultural spaces and places of entertainment, leisure and culture were not the only reasons that made her move to another country. There is also the perception of migration as a lifestyle marked by the possibility of knowing other places and their particularities, which includes accepting uncertainties about the future and the possibility of a more diverse life, which refers to aspects of her life related to new configurations of relationships (friends and lovers), the exposure to artistic manifestations of different modes of expression and the approximation with political issues overlooked in her coun try of origin.

Another process we identified is the adaptation to the new country of residence, which relates to mobility experiences. Marce who traveled to more places and covered greater distances (Table 2) among those places during a day had migrated to Buenos Aires five months before our interview. The modes of transport he reported using regularly were bicycle, bus, subway and train, all public transport. During the journey in which we accompanied him, Marce consulted the Moovit, Cómo Llego, Ecobici and Google Maps apps. Since arriving in Buenos Aires, he has been using those apps to facilitate his mobility. According to him, these apps have helped him adapt to the city. Marce argued that the process of adaptation to the new residential situation is related to knowing the new city, its streets, and its means of transportation. In this sense, to be spatially well located in the new city is one of the requirements of his feeling of belonging to it:

the applications helped me a lot. I have been living here for five months. And I still use them all the time. I mean, there are parts of my journey that I am already familiar with because they make up part of my routine. But, for example, when I go by bus, I use Moovit to know when to get off. In other words, I don’t stare out the window and I always know where I am, almost always! I am very happy to be able to adapt to such a big city so fast. Being very urban, I like mobility a lot, I like the street in general. This city is huge. I look out and see a street name that I don’t know and, without the app, I would be really lost. So, having used the apps to visualize, I now know more or less where I am, and if I see a particular (street) name, I know where I am. (Marce, 2017, November 29)

Moovit was his preferred app to choose routes from due to its multimodal feature and its notification system that alerts you when you are close to the stop you have to get off. Ecobici was useful for checking the availability of bicycles (his preferred means of transport) at the stations.

The experience of driving around the city on bicycles is an example of the arguments presented in the study by Caggiano and Segura (2014) that the mobility of migrants in the city is a matter of provisioning and definition of memberships: being able to access and being part of, “both phenomena are dealt with jointly” (p. 40).

In order to pick up a bicycle from any of the stations distributed in the city, the government requires a previous registration made online or in person at some of the citizen service stations. The registration requires an identification document and a certificate of residence. Only after sending these documents does the system allow access through the Ecobici app.

According to Didi’s statement, her confirmation of access and permission to use the bikes never happened:

Researcher: Have you already used the city bikes?

Didi: No, I never got it. That is, my papers, if they send you a card or a receipt that you have signed, and it never came. For me it’s very limiting that they let you use it (the bikes) only for an hour. Why is it an hour, right? And when it expires, they don’t let you take it out anymore. So if it’s more than an hour drive you get a ticket, I guess. What if you get hit or something and the hour goes by? It’s very limited. (Didi, 2017, December 13)

In contrast, Marce had access to the app through two accounts: one of his own, made from his own documents, and another that he had borrowed from his ex-boyfriend. When we accompanied him, one of the tours we took was on bicycles. With his account, he picked up a bike for himself; with the other, he picked up a bike for the researcher. As we headed to a station to pick up the bikes, Marce excitedly commented on his preference for bikes. In his reasoning, he referred to the sensations of autonomy, freedom and belonging that riding a bike in Buenos Aires generated in him. He emphasized his argu ments with an effusive “I feel that the city is mine”, while closing one of his hands in fist.

Belonging is also related to the residency fixing conditions. In this regard, one of the peculiarities we found refers to the difficulties of establishing residence due to the demands required by the real estate market to rent properties. Didi talked about the number of times she moved from one place to another in Buenos Aires:

no, when I got here I lived in a hostel in Colegiales... Then I lived with Pueyrredón and Marcelo T. (de Alvear). So I lived in Arcos, the district of Arcos, you know? Juan B. Justo and Santa Fe. And now I am here. I have moved a lot. Yes, because it is very difficult to get an apartment here, too. (Didi, 2017, December 13)

Marce’s testimony reinforced this argument. He lived in Buenos Aires for six months and said that he had lived for a few months with a friend in an apartment. He then rented a room in a residential house in the neighborhood of San Telmo and, at the time we interviewed him, he was moving in with his boyfriend into a friends’ apartment in the Flores neighbourhood while they were living in a city in the interior of the country.

Thomas’s experience was similar. He was 24 years old when we conducted the interview with him and was living with his older sister in the town of Berazategui, Buenos Aires state5. He and his parents are paraguayans who migrated to Buenos Aires a long time ago, when he was five years old. Then they returned to Paraguay, lived there for a while and years later settled again in Buenos Aires. His parents lived in Florencio Varela, another town in the state of Buenos Aires, with his younger siblings. At the age of 19, Thomas decided to leave his parents’ home and move alone to the city of Buenos Aires. He had relationship problems with them because they were very religious and did not accept his sexuality. They argued a lot about his way of dressing, talking, walking, and so forth. Thomas liked to wear heels and tighter clothes, which his parents did not consider

appropriate for a man.

When he first arrived in the city, he lived in a hostel in the Colegiales neighborhood. He could not say for how long he stayed there, but later decided to live with his sister in Berazategui to save some money. He worked in a store of a worldwide known coffee franchise in the Colegiales neighborhood. To avoid the daily commute from his sister’s house to his job, Thomas slept at friends’ houses for a few days a week. Among the reasons that prevented him from establishing residence alone in the city of Buenos Aires were his financial situation and his difficulty in dealing with the guarantees required by real estate agencies.

Conclusion

These data illustrate the connection between communication and mobility from a social practices perspective. We describe mobile-mediated travel experiences in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina, identifying specificities of inhabitants’ use of mobile devices. In this context, we focus on moments in which the specificities and daily commuting needs of the inhabitants, mediated by mobile transportation device applications, are intertwined with their life stories. The notions of migrations, flows, networks, places, subjects and objects in our diagram were important factors towards understanding the impact these specific devices have on the lives of the participants.

Four of the inhabitants we monitored were immigrants from Colombia, Paraguay and Venezuela. Considering the particularities reported by each of these four participants, we noted that imagine a life, adapt to a new set of local demands and create and establish belonging strategies are relevant processes experienced by them.

If migration is more focused on life stories, flows are concentrated on daily commuting. Both are determined by social practice. In the analysis we conducted on flows, we include the resistance to movement that the participants experience on a daily basis. Then, flows also refers to the effects of the instituted logic of time compression on the subjects who experience them in positive and negative ways with their bodies, objects and ideas. Only then we were able to realize social aspects of mobility mediated by mobile technologies.

Although partial, the results of this research indicated some specificities that showed continuity and revealed disruptions in people’s movement throughout the city. Communication and mobility structures shape daily travel experiences and condition lifestyles. Communication technologies, which act as mediators in this process, improve the parameters that operate in these molds. In this context, mobile devices are designed to contribute to the performance of subjects, objects and ideas, but they do not transform this logic. The mediated displacement experience does not always occur within these parameters.

texto em

texto em