Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

versão impressa ISSN 2184-0458versão On-line ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.8 no.2 Braga dez. 2021 Epub 01-Maio-2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.3532

Thematic articles

Professional (Re)Integration of Persons with Disabilities: Perceptions of the Contract Employment Insertion/Contract Employment Insertion+Measures by Beneficiaries and Promoters

1Centro Interdisciplinar de Estudos de Género, Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

The Portuguese State recognises the right of persons with disabilities to employment on equal terms with non-disabled persons. Nonetheless, many employers still resist the idea of hiring someone with a disability. For this reason, the action of the State is determinant to change attitudes towards disability and promote the hiring of persons with disabilities in the open labour market. These actions are materialised through public policies. This article reports the results of an exploratory and qualitative study on the measures known as contract employment insertion/ contract employment insertion+ (CEI/CEI+), implemented in the region of Lisbon and the Tagus Valley. It examined the perception of three stakeholders - 16 male and female beneficiaries with disabilities, nine institutions promoting these measures, and seven non-profit organisations devoted to training and employment of persons with disabilities - to know their perspectives on the potentialities and limitations of these measures. The results reveal that the CEI/CEI+ measures only provide a temporary remedy to the problem of unemployment among persons with disabilities, which hinders their access to a socioeconomically independent life that is sustainable. Nonetheless, respondents do not deny the importance of these measures, viewing them as an excellent opportunity to showcase their professional skills and reinforce their self-esteem and self-worth. The data obtained in this study are discussed according to various models approaching disability. In the end, we formulate a few recommendations to maximise the effects of these measures.

Keywords: persons with disabilities; public policy; professional (re)integration; CEI/CEI+ measures

O Estado português reconhece à pessoa com deficiência o direito ao trabalho, de forma igualitária às demais pessoas. No entanto, muitos empregadores resistem ainda à ideia de contratar uma pessoa com deficiência. Neste sentido, a ação do Estado é determinante para a mu dança de atitudes face à deficiência e para promover a contratação de pessoas com deficiência no mercado aberto de trabalho. Estas ações materializam-se através de políticas públicas. Este artigo reporta os resultados de um estudo de natureza exploratória e qualitativa sobre as medidas contrato emprego inserção e contrato emprego inserção+ (CEI/CEI+), realizado na região de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo, que analisou a perceção de três stakeholders - 16 beneficiários/as com deficiência, nove entidades promotoras das medidas e sete entidades promotoras de formação e emprego de pessoas com deficiência - com o objetivo de conhecer as suas perspetivas sobre os aspetos facilitadores e as limitações na aplicação destas medidas. Os resultados obtidos revelam que as medidas CEI/CEI+ apenas oferecem uma resposta temporária ao problema do desemprego das pessoas com deficiência, o que dificulta o acesso de forma sustentável a uma vida socioeconomicamente independente. Não obstante, os inquiridos não negam a importância destas medidas, considerando-as uma boa oportunidade para demonstrarem as suas competências profissionais e reforçar a autoestima e valorização pessoal. Os resultados obtidos com este estudo são discutidos à luz dos modelos de abordagem à deficiência e são formuladas algumas recomendações, com vista a potencializar os efeitos destas medidas.

Palavras-chave: pessoas com deficiência; políticas públicas; (re)inserção profissional; medidas CEI/CEI+

Introduction

Access to work is a fundamental right. In theory, everyone is equal before the law. Therefore, everyone should have the right to pursue a professional activity (Convenção dos Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência, 2006). On the one hand, this contributes to their economic survival and, on the other, to their happiness, fulfilment, and a sense of purpose (Associação Portuguesa de Deficientes, 2012; Simonelli & Camarotto, 2011; Vieira et al., 2015).

Nonetheless, persons with disabilities are still viewed as dependent, incapable, and ill (Vieira et al., 2015). In fact, they constitute one of the most disadvantaged groups in our society, both socially and economically. The prevailing negative view of persons with disabilities, which characterises the so-called “medical and individual model”, also extends to the world of labour.

Therefore, despite the guarantee and recognition of these rights, the fact remains that many persons with disabilities still face more significant difficulties when looking for work, not due to their physical or intellectual abilities, but due to the intersection of numerous social factors that restrict their employability, namely: discrimination and lack of disability awareness by employers; lack of accessibility in the workplace; employers’ ignorance regarding disability, including the specific needs and the particular skills of persons with disabilities; lack of effective incentive and support; failure to ensure that persons with disabilities effectively enjoy good quality education and training, resulting in a mismatch between their abilities and the needs of the labour market (Associação Portuguesa de Deficientes, 2012; Vieira et al., 2015).

Similarly to other public initiatives, the contract employment insertion/contract employment insertion+ (CEI/CEI+) measures were created to address some of these challenges, but, as far as we know, they have not been assessed yet to determine their adequacy and efficacy. This exploratory study strives to understand how the CEI/CEI+ measures are viewed by recipients with disabilities and promoting organisations. This study aims to assess how effective the measures mentioned above are, based on the perspective of their recipients and the organisations that promote them on the ground, con tributing to research on public policy and the professional (re)integration of persons with disabilities. From the data that we have gathered and analysed, we also reflect on how the implementation of these measures contributes to the perpetuation of individualised and stigmatising views of disability, or breaks with such views, highlighting that the State and society are responsible for creating conditions that allow the full participation of persons with disabilities in every realm of social life, including work and employment.

Before that, however, to provide a framework for our analyses, we will start by presenting a summary of different disability models and Portuguese public policy measures trying to promote work among persons with disabilities.

Theoretical Framework: From the Conceptualisation of Disability to Public Policy Regarding Professional Inclusion

Disability exists among all social classes and across the world. Nonetheless, the theoretical discussion on this subject is relatively recent and complex, besides being marked by various conceptual approaches (Organização das Nações Unidas, 1995; Pinto, 2012).

Restricting ourselves to the recent past - from the 20th century onwards - we should highlight the importance of the medical or individual model of disability, which mainly focuses on the insufficiencies and limitations of bodies with impairment, emphasising that they are incapable or abnormal (Fontes, 2009; Martins et al., 2012; Pinto, 2015). This model promotes an understanding of disability and reduces it to a problem that is intrinsic to the individual. Persons with disabilities are seen as different and inferior in aptitudes and skills. In turn, these characteristics are blamed for the difficulties that persons with disabilities face when it comes to full participation in society, at the same time as it absolves society from creating barriers that exclude persons whose bodies depart from the norm.

However, from the 1970s onwards, there was an intense questioning of this perspective, initially led in the United Kingdom by the Union of Physically Impaired Against Segregation. This group denounced the limitations of the medical model, developing a new understanding of disability, which has become known as the “social model of disability”. This new conception shifted the focus from the individual to society (Pinto, 2015), distinguishing between disability and impairment. The former refers to the social construct that excludes persons with disabilities, while the latter pertains to the individual’s biological characteristics (Fontes, 2009).

The emergence of the social model affected the lives of persons with disabilities in two ways. First, it allowed the identification of political strategies aimed at reducing barriers. If we consider that persons with disabilities are seen as different by the rest of society and kept from participating in it on equal terms, then eliminating these barriers should arise as a priority. The second aspect focused on the individuals with disabilities by replacing a medical view with a social one. In turn, this allowed persons with disabilities to think critically and to mobilise and organise themselves for the first time, demand ing to be treated as full citizens, on a par with others (Shakespeare & Watson, 2002). The social model gave rise to a new consciousness regarding the rights of persons with disabilities and the demand for public measures that enact these rights through social inclusion, extensive public policy, and the elimination of barriers (Fontes, 2009; Sousa, 2007). Nonetheless, some have argued that the social model, focusing on the social factors behind exclusion, has neglected the impact of impairment on the lives of persons with disabilities.

Therefore, more recently, the relational or biopsychosocial model has gained traction, “considering the interaction between biology and social context” (Pinto, 2015, p. 187). For example, the United Nations (UN) considers persons with disabilities those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which, interacting with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others (Convenção dos Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência, 2006). This understanding also prevailed in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Convenção dos Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência, 2006), adopted in 2006 by the UN general assembly. Today, this document constitutes an international reference for developing and implementing public policy in this area.

In Portugal, the biopsychosocial perspective is also present in current legislation. For example, Art. 4 of the Decree-Law no. 290/2009 (Decreto-Lei n.º 290/2009, 2009) of October 12, within a professional context, defines the employee with a disability as:

a person who presents significant limitations to their level of activity and participation, in one or several life domains, deriving from functional and structural changes of a permanent nature, whose interaction with the environment leads to continuous difficulties, namely in securing or maintaining a job or progressing in a career.

According to international law - for instance, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Convenção dos Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência, 2006) and other instruments produced by the International Labour Organisation -, workers with disabilities should benefit from special rights, such as adequate rehabilitation, useful employment, and wages equal to other workers without disability (Sequeira et al., 2006). Nonetheless, according to Fontes (2009), the ideology of the medical model still prevails in the realm of employment, where public policy mainly focuses on the supply side, not that of demand. As an example, note the substantial investment in the creation and implementation of subsidies for the integration of persons with disabilities into the job market, while it would make more sense to create workplaces that are accessible to every person, whether they have a disability or not. On the other hand, employers show discriminatory attitudes linked to their fears about a reality unknown to them. On this point, we should highlight the stereotypes about disability that associate it with diminished productivity, the fear that workers with disabilities may be more prone to injury, or may miss working more often due to health problems caused by their disability, or even the fear of backlash by clients or co-workers (Andrade et al., 2017; Fernandes, 2007). Other authors (Andrade et al., 2017) mention the lack of education pervasive among persons with disabilities, prejudice, and a lack of information as factors that make it harder for this population to enter the job market (Andrade et al., 2017).

The CEI/CEI+ measures aim to respond to some of these challenges within a vast public effort to promote training and employment of persons with disabilities in Portugal. Introduced in 2009, during the 17th Constitutional Governmental, they were created to improve employment levels and encourage long-term unemployed persons’ (re)integration into the labour market, including persons with disabilities, enacted by Decree no. 128/2009 (Portaria n.º 128/2009 ), of January 30, the CEI/CEI+ measures are similar, but they differ in certain aspects. The CEI focuses on unemployed persons (with or without disabilities) enrolled in employment services and receiving unemployment benefits. On the other hand, the CEI+ focuses on unemployed persons (with or without disabilities) enrolled in employment services and recipients of the social reintegration income. The CEI/CEI+ share the same guidelines, and they mainly strive to:

prevent and fight unemployment;

promote and support job creation;

encourage the professional integration of persons with more significant difficulties in entering the job market;

improve job quality;

foster local employment in economically disadvantaged areas, thus reducing regional disparities (Portaria n.º 34/2017, 2017).

These measures enable the long-term unemployed to perform socially valuable activities - the so-called “socially necessary work” - which consists of temporary activities/roles/tasks in public or private non-profit organisations (Portaria n.º 128/2009, 2009). We should note that these are not employment measures. Their main goal is to keep the long-term unemployed linked to the job market somehow. Therefore, they should be viewed to keep persons active, not as a substitute for work.

Methodology

The exploratory research on which this article is founded was conducted as a final requirement for a master’s degree in public management and policy, completed at the Institute of Social and Political Sciences of the University of Lisbon. The study involved semi-structured interviews with 16 beneficiaries of the CEI/CEI+: 10 men and six women. We have also interviewed seven officers from institutions devoted to training and finding employment for persons with disabilities and nine officers from institutions that promote CEI/CEI+ measures (two central public service institutions, two local public service institutions, and five private institutions of social solidarity). The interviews took place between June 4 and December 28 2018.

We have conducted this interview-based inquiry in Lisbon and the Tagus Valley region since it was the most convenient option. The selection of the institutions devoted to training and finding employment for persons with disabilities was also a choice of convenience.

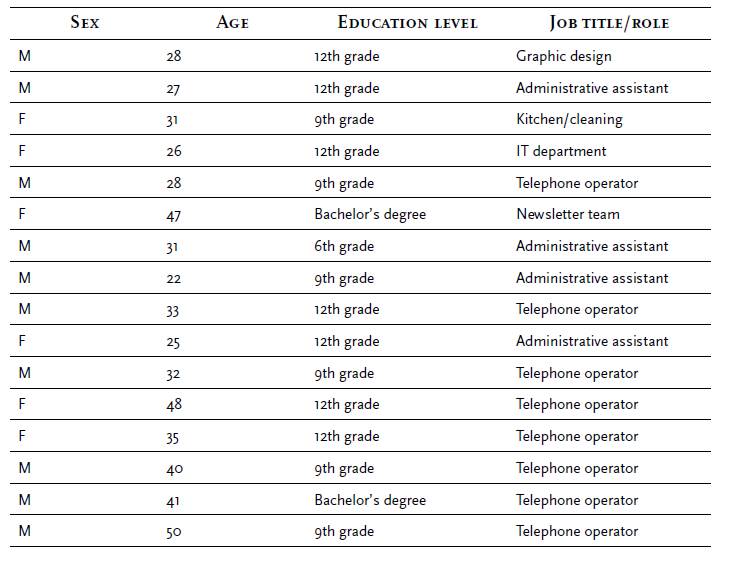

The contacts of the beneficiaries with disabilities participating in the study were provided by the institutions promoting these measures, where the subjects performed duties. Table 1 summarises the sociodemographic characteristics of our sample.

The group is primarily male, their mean age is 34 years old, and most have completed either 9th grade or 12th grade.

For data analysis purposes, a code was assigned to each group of stakeholders, namely: BD - for beneficiaries with disabilities; EP - for the entities hosting beneficiaries; OSL - for the non-profit organisations that train and find employment for persons with disabilities. A number was also assigned to each interviewee, corresponding to the order of the interview within the selected group.

Results

Our analysis focused on the experiences of the beneficiaries, employers, and institutions that train or find employment for persons with disabilities concerning the CEI/ CEI+ measures. We have tried to identify what they considered to be the positive aspects and limitations of these measures and suggest possible ways of improving them. Below, we highlight some of the results gathered in the interviews.

Positive Aspects of the Contract Employment Insertion/Contract Employment Insertion+

The three interviewed groups mentioned several positive aspects. The first pertains to the acknowledgement that the CEI/CEI+ measures help unemployed persons, emerging as an opportunity for the beneficiaries to demonstrate their professional abilities and skills. The three groups agree that participation in these programmes allows the beneficiaries to contact the world of work, thus creating or maintaining work habits and giving them a reason to leave the house. Moreover, they fight social exclusion and unemployment, increase the recipients’ self-esteem and responsibility, and acquire new experiences. Therefore, these measures constitute an opportunity to enter or re-enter the job market and to retrain or relearn: “a good thing about them is that they get you out of the house, we gain autonomy and have contact with the world of work, which then starts getting to know us, those are the most significant advantages” (BD16).

I think these measures are essential. As a public institution, we should welcome these measures ( … ) as a way to motivate them and allow them to have contact with the world of work, so they can acquire new experiences and see different realities ( … ) these projects might give them the opportunity to enter the job market because many have never worked. They do not have work habits, routines, or schedules, which will help them create these routines and follow them so they can have contact with the world of work. (PI2)

There is the question of training and retraining. Thanks to this measure, a person who had a particular profession a long time ago can now update their skills. I think that is the good thing about it. It allows a person to regain work skills. (NPO3)

Moreover, according to the three groups’ perceptions, the CEI/CEI+ measures are considered a springboard for the future professional integration of persons with disabilities, at least in some cases. That is the greatest hope of the beneficiaries, who expect to secure a permanent job and achieve an independent life - a desire shared by all adults. If we restrict ourselves to the promoting institutions and those that train and find employment, these measures also represent direct financial advantages for the former since they secure human resources. Even though these workers remain with the organisations for a limited amount of time, it is a way to reduce expenses with staff. In addition to this financial aspect, another noted advantage is that the institutions have up to 12 months to assess if the beneficiaries are good at performing a particular task, turning these measures into a valuable tool to filter and find competent workers at a reduced cost. “The advantages are entirely financial, besides the fact that we can discover valuable persons through these measures without that representing a high cost for the organisation” (PI3).

The CEI gives us the time to assess a person’s professional abilities. Today, public procurement does not give us enough time, so, for me, the CEI are crucial because they allow me to assess a person indeed. It’s extremely helpful to be able to say, “OK, this person has good skills, they will be a good worker”, or not. So, if there’s the chance, the person with a CEI contract can be more easily recruited. (OSL7)

Finally, the institutions promoting the training and employment of persons with disabilities believe that the CEI/CEI+ measures allow the trainees to practice what they learned during training and earn an income simultaneously.

Limitations of the Contract Employment Insertion/Contract Employment Insertion+

Despite recognising these advantages, the beneficiaries, promoting institutions and vocational training institutions have also pointed out many limitations. The first is that the workers’ monthly income is below the national minimum wage. That was the negative aspect most often mentioned by the three interviewed groups, who consider this income insufficient to face living expenses: “in terms of standard of living, this is not enough for us to live on because we want to build a life, have a house, be independent, and with this bit of money, we can’t” (BD14).

I have a basic contract + lunch subsidy + transport subsidy... all of that together is less than the minimum wage, and I feel that isn’t fair… I’m happy to be working here, of course, but I’d like to earn a bit more. (BD2)

Even though the goal of the CEI/CEI+ measures is not to replace a job, in many cases, that is what happens exactly. Many promoting institutions, especially the public sector, resort to these measures because they need human resources but cannot hire externally. That leads many promoters to undertake successive renovations of the measures CEI/CEI+ to address human resources needs which are permanent rather than temporary as the measures suggest: “the problem with public administration is that we can only hire internally or through external recruitment. external hires take ages, and there have to be authorisations and whatnot” (PI7).

There was always this juggling of deadlines, in the sense that when one was over, we applied for another, and when that was finished, we started applying for a new one. That was the only way to guarantee minimum services. ( … ) This measure isn’t well-thought-out. It’s a quick fix. For one year, we have this solution, and then we’ll see when there’s another CEI+. This can go on for one year, two years, three years, four years. (BD7)

One of the promoting institutions (PI7) reported they tried to hire a beneficiary after the CEI+ measure was over. Nonetheless, since the program only covers socially useful work, the institution found it hard to argue that the job performed by the beneficiary was vital:

it was a problem for us. How are we going to prove that what he’s doing is ‘socially useful’? He’s needed in the organisation, and that’s what we went with; we said he was an asset and had already shown various skills. We said that he would be integrated into the (name of the department), providing face-to-face assistance, writing to persons with disabilities, families, organisations, etc., but it wasn’t easy because of the socially helpful activities mentioned in the CEI+. (EP7)

Therefore, expectations are generated that rarely materialise: for the beneficiaries, who view the participation in a CEI/CEI+ programme as work and hope to see their CEI/CEI+ be transformed into a long-term work contract, which rarely happens; and for the promoting institutions that manage to address permanent staffing needs during 12 months, but at the end of this period see these workers leave and have to once more deal with unmet human resources needs.

Another limitation often mentioned by the promoting institutions and those devoted to vocational training is the excessive bureaucracy when applying for and implementing these measures. That is considered one of the main obstacles to their success: “often, we don’t resort to the CEI because it involves a lot of bureaucracy, and it takes a long time before a decision is made” (NPO7).

The IEFP (Institute for Employment and Vocational Training) provides funding, but we have to do the research ourselves. However, they could make the process easier and create a kind of manual of procedures that would be sent to all institutions ( … ) the information we find online is certainly our greatest help at the moment, but there’s so much information ( … ) and so detailed ( … ) see, sometimes we read all of the information, and it seems that point 2 cancels point 3, point 3 cancels point 1 ( … ) it’s a bit complicated, that’s what I’m trying to say. (NPO4)

The beneficiaries complain about fruitless attempts to obtain clarification, the excess of procedures, and contradictory information conveyed by different IEFP employees, as we can observe in the following testimonies:

I contacted them once to find out how many CEI+ were allowed in a single institution, and they gave me such a ridiculous answer that I haven’t called them again. Their answer was: “It depends on who is analysing”. And I said: “But there’s a law. What does the law say?” to which they answered: “Right, but it’s very vague; it depends on who is analysing”. I don’t know if the person on the phone simply didn’t know, or if they didn’t want to give me that information, but when I needed it and didn’t get it, my doubt was not solved. (BD7)

I sent a few emails but didn’t receive any timely replies. So all I could do, when the time came, was to say to someone in charge: “Here are the emails I sent, the calls I made, and these are the answers I obtained, so if we want to try this type of project again we need more time to plan things and greater persistence”. (BD10)

I’ve tried to contact them, and the experience was traumatising… the treatment I received was deplorable and plain awful. At a certain point, they told me: “Sorry, but what are you doing here? I’ve nothing for you; go home”. And I replied: “Forget it, I’ll look for something myself since I can’t count on you”. I think I only contacted the jobcentre twice, and both times were discouraging, even humiliating. (BD15)

In addition to bureaucracy, there are gaps in the IEFP services related to their online platforms, support lines and email, making it hard to obtain answers on time.

Furthermore, the beneficiaries recurrently mentioned a lack of inspection by the IEFP, which is another disadvantage since many institutions do not abide by the legislation regulating these measures, especially concerning the execution of “socially useful work” the non-occupation of a job position.

Even though the contract stipulates that the CEI/CEI+ measures do not employ the beneficiaries, only nine were actively looking for work from the 16 persons we have interviewed, which they primarily did online. Despite the majority worrying about not having a stable/permanent job, others have mentioned that they chose not to look for work. Five subjects said that they weren’t looking for a job because: (a) they feel content in the organisation where they perform their role/task and don’t see the need to look for a job; (b) they believe that the job market is not prepared to integrate persons with disabilities; and (c) they hope to join the program for the extraordinary regularisation of precarious employment contracts of the public administration (Prevpap).

Generally speaking, even though the CEI/CEI+ are not exclusively directed at persons with disabilities, they are seen as tools that allow youngsters with disabilities to transition into adult life, an alternative to being admitted into an occupational activities centre (CAO). Therefore, they act as a road map for the social and professional (re)integration of persons with disabilities. Because youngsters/adults with disabilities represent the possibility of an independent socioeconomic life, which everyone (with or without disabilities) expects, finally, it comes with significant financial advantages for the institutions promoting these measures.

Recommendations

We have also gathered recommendations for improving the CEI/CEI+ measures, with the view to making them more efficient. The first recommendation put forth by most of the persons interviewed in the three groups pertains to more promptness and a more efficient and rigorous inspection by the IEFP. Moreover, they suggest that the procedures be revised, making them less bureaucratic and lengthy, which is one of the main obstacles to joining the CEI/CEI+ program. Besides the need to simplify, they also suggest that the IEFP delegate part of its powers to the resources centres, allowing the latter to assess candidates’ profiles more thoroughly to properly match their skills and limitations to the roles that they perform:

I think persons should be more closely supported since they aren’t used to routines, struggle with schedules, and have never worked before in many cases. I’ve noticed that they sometimes find it hard to conform to the project’s rules, namely regarding attendance. (PI2)

IEFP has few resources in many of its structures, and sometimes the structure itself rests too heavily on bureaucracy. As a consequence, these youngsters are somewhat abandoned. It requires an institution willing to deal with the matter and spend months chasing papers, and sometimes their certificates have errors, and you need to talk to the institution. So, this backstage work needs to be done and that sometimes they can’t do it themselves. If no one does it, the process dies. (PI6)

Another recommendation has to do with the continuity of the measures after the end of the contract when the worker is competent, and the organisation is willing to keep them. That would turn the experience into a permanent contract that the State financially supports so that the beneficiaries can become permanent workers and tax-payers, similar to workers without disabilities:

it would be helpful if the organisation had an automatic integration scheme to become permanent employees. I think that would be the most useful measure since we are talking about public institutions that actually need persons, and there are certain tasks where persons can really be put to good use. (BD15)

Moreover, it was generally recommended to reinforce the practices used by the IEFP to raise awareness, inform, dispel doubts and myths, and intensively fight ignorance around the issue of disability. It was also stressed by many that there should be more effective public policy centred on intervening in schools as a way to demystify and fight against the stereotypes that still prevail about disability:

there’s no doubt that education is crucial... a few years ago, we did a study on the profile of employers who hired persons with disabilities, and we concluded that most had known persons with disabilities, at a professional or personal level. If we had a truly inclusive society, where everyone had a voice, if children were familiarised with diversity and inclusion from early on when they become entrepreneurs and joined the work world themselves, things would be completely different. So, it would have a positive effect in terms of demystifying prejudice and stereotypes. We must certainly start from there. (NPO6)

Conclusions and Discussion

The article presents the actual results of an exploratory scientific study. The data we have gathered suggests that the CEI/CEI+ measures are a short-term solution and that they generally fail to offer sustained access to the job market after the temporary measures have ended. Nevertheless, by joining these programmes, the beneficiaries create the expectation of securing a long-term job, developing a relationship with the institution and co-workers, and hoping to remain as employees after the CEI/CEI+ contract has ended. Upon seeing their expectations unfulfilled, many interviewees realise that these contracts do not serve as springboards into the job market. With the meagre income during the programme, accessing an independent socioeconomic life becomes an almost impossible dream.

Moreover, one of the main problems mentioned is using the CEI/CEI+ measures to meet permanent staffing needs. That goes against the legislation that regulates the CEI/ CEI+, according to which the focus should be on “socially useful work”. Nonetheless, many social institutions adhering to the CEI/CEI+ programme are financially fragile, which keeps them from hiring permanently. As for the institutions of the central/local administration, they believe that the hiring process following the end of the CEI/CEI+ is too bureaucratic and complex - they must request a permit before they can open a public recruitment process, which is lengthy and cumbersome (i.e., rendering this possibility impractical). Therefore, in both cases, the CEI/CEI+ measures have practically no effect on creating long-term jobs. In fact, in 2014, a union leader defended in a press conference that the CEI/CEI+ “are nothing but a way of ‘removing a few unemployed from unemployment statistic’” (“‘É Urgente Pôr Fim à Exploração dos Desempregados’, afirma CGTP”, 2014, para. 2).

In summary, to answer the primary question posed in this research - how are the CEI/CEI+ viewed by the beneficiaries with disabilities and promoting institutions? -, our data suggest that, even though these measures do not produce the expected results, the three groups we have interviewed recognise their importance. It constitutes an excellent opportunity for the beneficiaries to showcase their professional skills, allowing them to create/maintain work habits. Moreover, they provide professional and personal fulfilment. The institutions that adhere to the CEI/CEI+ measures highlight the financial benefits associated with them and the opportunity to assess the professional skills of the workers. In other words, they believe that these programmes constitute powerful tools for finding good workers at a reduced rate. Finally, the organisations that promote the vocational training and employment of persons with disabilities see them as an opportunity for trainees to practice the skills they acquired during training and receive an income in the process.

Reflecting now on these results from the perspective of the disability models we mentioned earlier, we must conclude that the CEI/CEI+ measures are insufficient to remove barriers and rectify the exclusion to which persons with disabilities are subjected in the job market. They might even have perverse effects. As we have seen in the analysed sample, these programmes favour the use of low-cost labour. Consequently, they cannot guarantee true financial independence for those who benefit from them. Moreover, they do not directly contribute to creating long-term jobs, despite frequently solving the permanent staffing needs of the promoting institutions. These measures are presented to improve the employability of workers in a particular unemployment situation and stimulate their (re)integration into the labour market. However, they can reinforce the social perception that the failure to secure a stable job is due to their impairment (cf. medical or individual model), and not to the structural obstacles these persons face when they try to get a job (which reflects the biopsychosocial model).

The conclusions presented here are based on the data we have gathered, but they are not a point of arrival - they should serve as the starting point of a more extended and more complex discussion. Even though many governments are increasingly concerned with the vocational training and employment of persons with disabilities, the materialisation of these goals has undoubtedly been slow.

However, “not to throw the baby out with the bathwater” is crucial. Despite the fragilities that we have found, which should be corrected, there are positive aspects to these measures that should be expanded and reinforced. Therefore, we believe it is necessary to pursue a scientific and political reflection around this subject, taking into consideration the recommendations of the interviewees, namely: greater agility and less bureaucracy in the IEFP processes; consideration of alternatives to long-term hiring after 12 months (maximum duration of the CEI/CEI+); creation of an efficient inspection team by the IEFP, which should devote itself to the employability of persons with disabilities; raising the monthly income to the same level as the Portuguese minimum wage; elimination of the “socially useful work” category; delegation of powers from the IEFP to the inclusion resource centre, which should manage these processes; the IEFP should work on raising awareness and demystifying disability among public and private organisations, to fight obstacles that keep persons with disabilities from being hired.

In a follow-up to this investigation, we also recommend developing further research to ascertain the number of persons with disabilities who enter the job market (by signing a long-term work contract) after completing the CEI/CEI+ period.

Acknowledgements

The translation of this article was funded by national funds through Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), I.P., under project UIDP/04304/2020.

REFERENCES

Andrade, A., Silva, I., & Veloso, A. (2017). Integração profissional de pessoas com deficiência visual: Das práticas organizacionais às atitudes individuais. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 17(2), 80-88. https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2017.2.12687 [ Links ]

Associação Portuguesa de Deficientes. (2012). O emprego e as pessoas com deficiência. Instituto Nacional para a Reabilitação. [ Links ]

Convenção dos Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência, 13 de dezembro, 2006, https://www.inr.pt/resultados-de-pesquisa/-/journal_content/56/11309/44797?p_p_auth=jZgndlTI [ Links ]

Decreto-Lei n.º 290/2009. Diário da República n.º 197/2009 - I Série (2009). https://data.dre.pt/eli/dec-lei/290/2009/p/cons/20150617/pt/html [ Links ]

“‘É urgente pôr fim à exploração dos desempregados’, afirma CGTP”. (2014, 1 de dezembro). Esquerda. https://www.esquerda.net/artigo/e-urgente-por-fim-exploracao-dos-desempregados-afirma-cgtp/35005 [ Links ]

Fernandes, C. (2007). Empregabilidade e diversidade no mercado de trabalho - A inserção profissional de pessoas com deficiência. Cadernos Sociedade e Trabalho (8), 101-113. [ Links ]

Fontes, F. (2009). Pessoas com deficiência e políticas sociais em Portugal: Da caridade à cidadania social. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 86, 73-93. https://doi.org/10.4000/rccs.233 [ Links ]

Martins, B., Fontes, F., Hespanha, P., & Berg, A. (2012). A emancipação dos estudos da deficiência. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 98, 45-64. [ Links ]

Organização das Nações Unidas. (1995). Normas sobre a igualdade de oportunidades para pessoas com deficiência. Secretariado Nacional para a Reabilitação e Integração das Pessoas com Deficiência. [ Links ]

Pinto, P. (2012). Dilemas da diversidade: Interrogar a deficiência, o género e o papel das políticas públicas em portugal. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian; Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. [ Links ]

Pinto, P. (2015). Modelos de abordagem à deficiência: Que implicações para as políticas públicas? Ciências e Políticas Públicas, 1(1), 174-200. [ Links ]

Portaria n.º 128/2009, Diário da República n.º 21/2009, Série I de 2009-01-30 (2009). https://data.dre.pt/eli/port/128/2009/1/30/p/dre/pt/html [ Links ]

Portaria n.º 34/2017, Diário da República n.º 13/2017, Série I de 2017-01-18 (2017). https://data.dre.pt/eli/port/34/2017/p/cons/20200827/pt/html [ Links ]

Sequeira, A., Maroco, J., & Rodrigues, C. (2006). Emprego e inserção social das pessoas com deficiência na sociedade do conhecimento: Contributo ao estudo da inserção social das pessoas com deficiência em Portugal. Revista Europeia de Inserção Social, 1(1), 3-28. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.12/1856 [ Links ]

Shakespeare, T., & Watson, N. (2002). The social model of disability: An outdated ideology? Research in Social Science and Disability, 2, 9-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3547(01)80018-X [ Links ]

Simonelli, A., & Camarotto, J. (2011). Activity analysis for inclusion of disability people at work: A proposition model. Gestão & Produção, 18(1), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-530X2011000100002 [ Links ]

Sousa, J. (2007). Deficiência, cidadania e qualidade social: Por uma política de inclusão das pessoas com deficiências e incapacidades. Cadernos Sociedade e Trabalho, (8), 38-56. [ Links ]

Vieira, C., Vieira, P., & Francischetti, I. (2015). Professionalization of disabled people: Reflections and possible contributions from psychology. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 15(4), 352-361. https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2015.4.612 [ Links ]

Received: August 15, 2021; Accepted: October 04, 2021

texto em

texto em