Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista Lusófona de Estudos Culturais (RLEC)/Lusophone Journal of Cultural Studies (LJCS)

versión impresa ISSN 2184-0458versión On-line ISSN 2183-0886

RLEC/LJCS vol.10 no.1 Braga jun. 2023 Epub 30-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/rlec.4216

Thematic Articles

Interactions Between the Gramado Film Festival Museum, the Film Festival and the Local Cultural Tourism

i Departamento de Educação, Universidade Luterana do Brasil, Canoas, Brazil

This study is part of the theoretical field of cultural studies and chooses as its object of analysis the Gramado Film Festival Museum and its links with the Film Festival and local cultural tourism. The main goal is to reflect on the museum as a hybrid cultural producer, which triggers, through interactivity, representations of the Film Festival and the city of Gramado itself, producing multiple meanings among its visitors and boosting local cultural tourism. In this sense, some questions are pivotal to this study: what representational strategies are used in the permanent exhibition at the Gramado Film Festival Museum? What cultural representations does the museum communicate about the Film Festival and the city of Gramado? As a methodology, we used the ethnographic observation of the museum’s permanent exhibition with records in a field diary. Among the contingent and provisional findings, under the aegis of postmodern cultural convergence, the modulation of culture and art in the museum’s permanent exhibition stands out, producing multiple connections between the Film Festival, the museum and cultural tourism in the city from Gramado.

Keywords: Gramado Film Festival Museum; Film Festival; cultural tourism

Este estudo se inscreve no campo teórico dos estudos culturais e elege como objeto de análise o Museu do Festival de Cinema de Gramado e suas articulações com o Festival do Cinema e o turismo cultural local. O objetivo central é refletir sobre o museu como um produtor cultural híbrido que, através da interatividade, aciona representações sobre o Festival do Cinema e acerca da própria cidade de Gramado, produzindo múltiplos significados entre os seus visitantes e dinamizando o turismo cultural local. Nesse sentido, algumas questões são centrais neste estudo: quais as estratégias representacionais acionadas na exposição permanente do Museu do Cinema de Gramado? Que representações culturais o museu comunica sobre o Festival de Cinema e a cidade de Gramado? Em termos metodológicos, utilizou-se a observação etnográfica da exposição permanente do museu com registros em um diário de campo. Dentre os achados contingentes e provisórios, destaca-se, sob a égide da convergência cultural pós-moderna, a modulação da cultura e da arte na exposição permanente do museu produzindo múltiplas articulações entre o Festival do Cinema, o museu e o turismo cultural na cidade de Gramado.

Palavras-chave Museu do Cinema de Gramado; Festival do Cinema; turismo cultural

1. Introduction and Methodological Assumptions

The choice of the theoretical contribution of cultural studies to mobilise the analysis of the object of study at issue, the Gramado Film Festival Museum (http://www. museufestivaldecinema.com.br), is related to the fact that it is a field of interdisciplinary studies. According to Wortmann et al. (2015), it has enabled the proposition of considerations about the productivity of culture in educational processes underway in contemporary society. In that way, the concept of cultural pedagogies stands out. For Steinberg (2016), it is related to the educational dimension, considering that currently, learning has been moving to other sociocultural and political spaces beyond the school. “Education takes place in a variety of social sites including but not limited to schooling. Pedagogical sites are those places where power is organised and deployed including libraries, TV, movies, newspapers, magazines, toys, advertisements, video games, books, sports, etc.” (Steinberg & Kincheloe, 2004, pp. 101-102).

Assuming that the Gramado Film Festival Museum has an educational dimension, this study aims to explore what cultural meanings are produced and disseminated by the permanent museographic exhibition of this museum to its visitors.

As for methodology, visits to the museum were made within an ethnographic perspective of participant observation and records that intended to understand, according to Souza and Lopes (2002), the materiality of this exhibition, giving the observer an insight into the most recurrent representations produced in its various materials. Each of the on-site tours, and the notes and photographs taken in each opportunity, are part of the ethnographic research effort that sought to produce the empirical material of the research. It is worth noting that authors such as Coffey (1999) recognise that this methodology is often associated with the researcher’s “self”, thus becoming autoethnography. Hence, this study was made possible through an autoethnographic practice that required, as already mentioned, visits to this museum space, whose observations were recorded in a field diary composed of the researchers’ notes and photographs they took. The analyses were developed from the cultural analysis’ contribution, which, according to Silva (2010), seeks to question naturalised views about the cultural spaces of the museum and the meanings produced and shared by visitors of these spaces. In light of these contributions, the choice for autoethnography is established by its potential for evaluating and re-evaluating the researcher’s observations and results. That is, therefore, the methodological premise adopted in this research.

Regarding the theoretical interpretation of museums in contemporary society, we share Hudson’s (1999) notion that museums have been steadily evolving from mere warehouses, independent units of preservation of national symbols, to cultural centres and powerful educational forums. This concept will be discussed in the section 3.

Firstly, we will make a brief historical introduction about the Gramado Film Festival to understand this festival museum as a cultural artefact, which in its permanent exhibition, produces representations of this film event and the city of Gramado, thus contributing to increasing the local cultural tourism. According to Lasanski (2004), this museum is simultaneously a cultural product and a producer of culture which promotes cultural tourism when it identifies and attributes particular interpretations to the cultural heritage of the city of Gramado. In this sense, we seek to analyse the hybrid potential of the Gramado Film Festival Museum as an interactive cultural forum that builds representational strategies about the Film Festival and this city. Thus, some questions are essential in this study: which representational strategies are used in the exhibition design of this museum? What cultural representations does the museum communicate about the Film Festival and the city of Gramado? What possible cultural pedagogies does the museum convey to its visitors? These are some of the questions we intend to address in this article.

2. The Gramado Film Festival

The genesis of the Film Festival is associated with the first tourism event in Gramado, four years after the emancipation of the city: the Hydrangea Festival in 1958, which, according to the Municipal Education Secretary of Gramado (Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Gramado, 1987), was a simple festival alluding to the flower that symbolises the city.

However, the Festa das Hortênsias had an unexpected repercussion, promoting the city as the first milestone in the history of organised tourism in Rio Grande do Sul. At the time, the then secretary of the Municipal Council of Tourism, Romeu Dutra, thought of giving a cultural imprint to the event by including film screenings. According to Daros (2008), the first cinema in the city, called 3 de Outubro, opened in 1929 and was located in a wooden house in the Major Nicoletti Square. Quintans (2008) states that this building was also used for other community activities because often, the seats were removed to clear the centre of the hall for dancing or skating. With the advent of sound film in 1936, this cinema got new seats and a more modern screen, changing its name to Cine

Splendid, which played a fundamental role for the community and was considered the “city’s hot spot”. However, in the early 1960s, due to the precariousness of the building, Cine Splendid ceased its activities.

It was only in 1964, during the administration of the Mayor José Francisco Perine, that the construction of a new cinema began. In 1967, Cine Embaixador was inaugurated, and on the occasion of the “VI Hydrangea Festival”, from January 6 to 8, 1969, the “I National Film Festival of Gramado” was held. According to Quintans (2008), it was attended by prominent artists of the national cinema of that time, such as Eva Wilma and John Herbert. Given the event’s success, a second edition was held in 1971, still an amateur event with no awards.

According to Quintans (2008), after the administration of Mayor Horst Volk, with the creation of the Secretariat of Tourism, the film screenings became a nationally prominent film festival. The author explains that the public administration of that time, based on contacts with film producers from Rio de Janeiro, offered sponsorship for the city to be the scenery of film productions, which was essential for the creation of the Gramado Film Festival. According to the statements of the Secretary of Tourism at the time, Romeu Dutra:

we then helped and sponsored all the artists’ expenses during the filming. Meanwhile, we took the opportunity to discuss with important names, such as Paulo José and Lewgoy, the creation of a festival in Gramado. Lewgoy arranged for the first audience to talk to the president of the National Film Institute, Ricardo Cravo Albin. (Quintans, 2008, p. 40)

Thus, the first edition of the Gramado Film Festival was held from January 11 to 14, 1973, causing some controversy in the city. Quintans (2008) states that at that time, Gramado did not have hotels with swimming pools, so the artists used to go to the Gramado Tennis Club, a recreational space for the residents in the summer. In this place, the film stars were topless, a practice that impacted the citizens of Gramado, as described by the author: “in fact, it was a scandal! The priest made a speech in church about the threat the festival represented to the Gramado family, raising doubts about the continuity of the event that had been so arduously accomplished” (Quintans, 2008, p. 45). However, Quintans (2008) emphasises that the event took place anyway because Horst Volk, back to the presidency of his company, the Calçados Ortopé, sponsored the Festival, so in this edition, the city that at the time had 24,000 inhabitants received approximately 16,000 visitors.

Since the Film Festival’s first edition, the event’s closing evening was dedicated to the awards ceremony. Quintans (2008) recalls that Horst Volk wished the trophy would be a hydrangea sculpture. However, “Kikito”, the Brazilian Oscar, was created by Elisabeth Rosenfeldt, at the headquarters of Artesanato Gramadense, in 1966 before the Film Festival was created. It was a small lead statuette that, according to Daros (2008), this artist created to give to her closest friends as a symbol of friendship and respect. It was affectionately known as the “God of good humour”. In 1972, the Kikito was the trophy of the National Handicrafts Fair, hosted in Gramado. Then, in 1973, it became the Film Festival’s highest award for the best artists and directors.

With the event’s expansion, every edition, the Cine Embaixador, with its 600 seats, became small to house the festival. In 1987, according to Daros (2008), with resources provided by the community and a loan from the City Hall, about 55,000,000 cruzados were invested in renovations and technical improvements to ensure the highest standard for the headquarters of one of the biggest national film events. It is worth mentioning that during this refurbishment, the cinema grew to house 1,100 people. Moreover, its architectural style, mostly Bavarian, was already predominant in the city since the early 1960s, aiming to give Gramado an architectural identity, as can be perceived in Romeu Dutra’s words:

the Bavarian style was established at that time for the constructions in Gramado. We thought of many things, and the person who gave us many ideas about the Gramado style was Frantz Habeler, who owned the Hotel das Hortênsias. He was a German who had sold his property in Porto Alegre and decided to build that hotel, unlike the square style that prevailed at the time, those square houses. (Quintans, 2008, p. 38)

Daros (2008) points out that with this renovation, mainly by incorporating the Bavarian style into the building, the cinema headquarters were given a new name: Palácio dos Festivais. Five years after its inauguration, the continuity of the Film Festival was threatened by a lack of government support. However, according to Sebrae (2022), filmmakers launched an Iberoamerican edition in 1992, awarding films and international stars, such as actor Javier Bardem and filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar.

In 2006, before its 33rd edition, the Gramado Film Festival was acknowledged as a historical and cultural heritage of Rio Grande do Sul, under Law no. 12.529, of June 6, 2006. Zeca Brito, director of Lecine, and Beatriz Araújo, State Secretary of Culture, in an editorial section of the Festival’s 50th edition catalogue prepared by Gramadotur, highlighted:

as a fundamental part of the gaucho cultural heritage. In the last 50 years, Gramado has been promoting Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil and abroad, making the municipality a cultural and tourism reference. Gramado is a creative economy ecosystem that evolved from a calendar of cinematographic actions (Brito & Araújo, 2022, p. 17)

Thus, the event represented the consolidation of the tourism activity in Gramado. According to Brito and Araújo (2022), the acknowledgement of the municipality as a tourism success case happened mainly because of the Film Festival. Gramado was soon referred to as the “Brazilian capital of cinema” (Secretaria Municipal de Educação, 1987, p. 87).

Following the coronavirus pandemic, in 2020 and 2021, the festival was held online. In 2022, the event resumed on-site, and its 50th edition was celebrated with two major milestones: the Municipal Legislative Assembly approved Bill no. 028/2022 (Projeto de Lei do Legislativo n.º 028/2022, 2022), establishing the Kikito as cultural heritage of the city of Gramado (“Cerimônia Oficializa Kikito Como Patrimônio Cultural de Gramado”, 2022); and the reopening of the Gramado Film Festival Museum, whose origins date back to the year 2000. However, the installation of the museum was only made possible in 2015 through a bill from the municipal executive power.

3. The Film Festival Museum Under the Theoretical Lenses of Cultural Studies

According to Urry (2001), in contemporary times, with the decline of the national historical narrative hegemony, “there has been a remarkable increase in the scope of histories worth being represented” (p.175) in museums. Thus, the theorist claims that postmodern museums are now exhibiting alternative histories with social, economical, popular, feminist, ethnic and industrial biases. Moreover, the author (Urry, 2001) draws attention to the change in the interaction of the visiting public with museums:

visitors are no longer expected to stand awestruck at exhibitions. More emphasis is now placed on their degree of involvement. “Living” museums replace “dead” museums, open air museums replace enclosed museums, sound replaces murmurs imposed by silence, and visitors are no longer apart from what is on display by glass partitions. (Urry, 2001, p. 176)

Such interactivity, and the increased visitors’ participation in exhibitions, according to Hudson (1999), stem from the change in the scope of museums, which started to pose questions to the public, instead of providing them with answers, encouraging them to interact and build their understandings through what they observe, listen to and manipulate. According to Lumley (1988), hybrid museums, in their exhibitions, activate interactive styles, which lead to the production of a media environment. Following this approach, Anico (2005) states that contemporary museums no longer focus on the unbridled acquisition of objects but on communication with the public. According to the author, there has been a change in the “museological ethos”. Where formerly objects were valued, the visitor has become the central focus. The public becomes “both agent and product of political, social and cultural change” (Anico, 2005, p. 83). Moreover, the exhibition design project establishes an active participation of the visiting public with the digital collections, particularly in interactive museums, as is the case of the Gramado Film Festival Museum.

Thus, by adopting these theoretical assumptions, this study seeks to examine the Gramado Film Festival Museum not only as an informational repository of this event, but mainly as a producer of culture that disseminates and communicates representations about the Film Festival and the city of Gramado, promoting the local cultural tourism. The museum’s implementation process and the analyses made possible through the visits are discussed below.

4. The Gramado Film Festival Museum

The roots of this museum’s implementation date back two decades ago, as from Municipal Law no. 1738/00 (Lei 1738/00, 2000), of June 15, 2000, which authorised the institution of the Gramado Festivals Archive and Museum. At that time, the museum was under the tutelage of the historian from Gramado, Iraci Koppe, and located next to the Municipal Culture Centre, which still houses the Municipal Historical Archive.

In 2015, through Bill 042.15 (Projeto de Lei do Executivo - PLE 042.15, 2015), the Gramado administration granted the use of public property next to the Palácio dos Festivais to be used for the implementation and operation of the Film Festival Museum. This concession was granted through a bidding project, announced through a public bid notice, which could also include the installation of a cafeteria and a souvenir shop. According to this regulation, this museum’s creation is founded on the following grounds:

since 2006, through Law 12.529, the Gramado Film Festival became part of the Cultural and Historical Heritage of Rio Grande do Sul, which has been held uninterruptedly for 43 years as a national and international reference. Through this project, we propose the Implantation of the Gramado Film Festival Museum upon the approval of this Law. (Projeto de Lei do Executivo - PLE 042.15, 2015, p. 2).

It also highlights that it should have the following goals:

provide visibility for the Museum among its target audiences, presenting it as an attraction of interest among the many options Gramado offers. Stimulate a high flow of visitors to the Museum facilities. To associate the name of the Museum with the prestigious image and consecrated brand, the Gramado Film Festival, promoting positive synergies between the communication efforts of one and the other. (Projeto de Lei do Executivo - PLE 042.15, 2015, p. 2).

The Gramado Film Museum is associated with the Film Festival as a cultural attraction that seeks to consolidate tourism in the city of Gramado. Thus, on October 26, 2016, the Film Festival Museum was inaugurated. Its collection includes the Film Festival posters, journalistic reports, photographs, and panels with audiovisual resources to present both information about the event’s history and its editions and the history of the development of the silver screen in the world and Brazil.

The Museum was closed during the coronavirus pandemic, between 2020 and 2021. It reopened in 2022 on the anniversary of the 50th edition of the Film Festival, focusing on the interactivity of the public with the collection, which earned it the title of the first contemporary interactive film museum in Latin America.

To analyse the meanings and the most recurrent cultural pedagogies that the Film Festival Museum produces and conveys to its visitors in its exhibition design, we produced observations recorded in a field diary from the 10 visits to this museum space over four weeks. For the analyses, we selected four thematic axes, as follows.

4.1. The Building and Architecture of the Film Festival Museum

The building of the Film Festival Museum is adjacent to the Palácio dos Festivais, and the entrance is the same hall that hosts the Film Festival. It has a shared floor plan with the Palácio dos Festivais, which strengthens the bonds between them for one or the other’s visitors. On the other hand, the Bavarian architectural style reinforces the tourist image of Gramado as a European city, as shown in the Figure 1.

The Bavarian architectural style, with German origins, alludes to the city’s colonisers and is featured in many other buildings, such as the Banco do Brasil and the Post Office buildings. From Urry’s (2001) theoretical perspective, this alternative may explain the “apparent aspiration, among people living in certain places, to preserve or implement buildings, at least in their public spaces, that embody that particular place where they live” (p. 170). The theorist adds the effect of this alternative to attract the tourist’s eye because, according to him, when people visit inland cities, the buildings that set this place apart from other locations draw their attention. In this interrelation between architecture and tourism, architecture is simultaneously a place, an event, and a sign. It is planned as a representation, reception, use, entertainment and commodification process.

Entering the Museum, one can immediately observe a large concrete statue of Kikito (Figure 2), produced by Elisabeth Rosenfeldt in her studio in 1967 and, later, bought by the Berg couple, who donated it to the Gramado City Hall. It was transferred to the entrance hall of the Palácio dos Festivais during the 23rd edition of the event in 1996. The Kikito is the Film Festival’s highest award for each edition’s best artists and directors. Elisabeth Rosenfeldt, its creator, chose the name. It is also known as the “God of good humour”. According to Daros (2008), its smile represents an invitation to learn a lesson from its creator: “smile with it and learn the lesson of its mother Elisabeth: when you have good humour, joy, and do what you need to do with pleasure, then life has the beauty and happiness that we all seek” (p. 265).

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 2 The concrete sculpture of Kikito at the entrance of the Palácio dos Festivais

Walking past the great Kikito, towards the stairs that connect the Palácio dos Festivais to the Museum building, one can see several digital screens with rotating images, displaying banners and posters promoting each of the 50 editions of the Film Festival, as shown in Figure 3.

Interestingly many of the Film Festival posters promoting the event feature images of hydrangeas, the tourist landmark of the city, associating the Museum to this tourism icon of Gramado, as seen in Figure 4.

According to Daros (2008), the hydrangea was brought to Gramado by Leopoldo Lied, one of its first residents, when it was still part of the city of Taquara in the early 1930s. It was planted mainly on the slopes to prevent erosion. However, the historian points out that the flower went from being an ecological agent to becoming a tourist attraction in the region.

The press gradually showed us the value of our work planting and caring for the hydrangeas. They called it an “admirable spectacle”, which seemed to be “in a piece of heaven”. And we woke up for something bigger, which was TOURISM. The tourism germinating in our land, next to the roots of the hydrangeas, was planted and planned. (Daros, 2008, p. 229)

From this excerpt, one can infer that the tourist activity in Gramado was driven by hydrangeas, the flower that symbolises the city. There is even a day in the municipal calendar dedicated to its celebration. Rojek and Urry (1997) point out that tourist practices involve not only the purchase of specific goods and services, but also the consumption of signs. In that way, the authors consider tourists as semioticians who seek landmarks that confer uniqueness to the place. The theoretical constructs of these authors suggest that hydrangeas were associated with the city of Gramado as representational practices of tourist interest. Moreover, their inclusion in the Film Festival’s promotional posters demonstrates the reach of these representational systems in the Film Museum. These digital screens surrounding the museum entrance illustrate some of the numerous technological resources available in this space, which will be discussed in the next topic.

4.2. Museographic Strategies and Interactivity at the Film Festival Museum

Before introducing the features of this museum space, especially regarding the massive technological resources, it is essential to address their impacts on the exhibition. Among them, the concept of interactivity stands out. According to Lupo (2021), it

has been widely used as a premise for the institutional structure of museums, often introduced in the museum space in recent decades. Interactive museography often emerges as an alternative approach for displaying collections built from digital databases, actively participating in the constitution of museums seen as reference centres and creating museum narratives. (p. 401)

Thus, it is possible to anticipate that interactive museography is established as an alternative to the upsurge of the so-called “museums without collection” due to the constant challenge of conforming the assets for the exhibition, as in the Museu do Futebol, in Rio de Janeiro, according to Lupo (2021). It also emerges as an opportunity to display the increasing diversity of themes regarded as museological and heritage objects.

According to this author, the digital collections that have become many of today’s museums yield a greater public engagement with the exhibition content because “interactivity emerges as a key mediator to ensure the relationship between the museum and its public, suggesting and encouraging the active participation of visitors in the processes of signification undertaken by the museum institution” (Lupo, 2021, p. 405).

Regarding the Film Festival Museum, among its digital museographic strategies, there is a timeline complemented by explanatory panels for the respective highlighted dates (Figure 5) and sound reception systems made available to visitors for introducing both the history of the Festival and the emergence and development of the seventh art in the country and the world.

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 5 Panel with the timeline of the history of national cinema indicating 1973 as the year of the 1st edition of the Film Festival

The panel “Festival in Decades” has audiovisual resources which, through five screens, show the awards and relevant facts of the Film Festival in each of its five decades of history (Figure 6).

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 6 Interactive exhibition of the Gramado Film Festival by decades

As another communicational strategy, digital screens present media highlights for each of the Festival’s editions, displaying the posters of the films awarded throughout half a century of the event (Figure 7).

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 7 National repercussions of the event’s editions (left) and the announcement of the films awarded in the event (right)

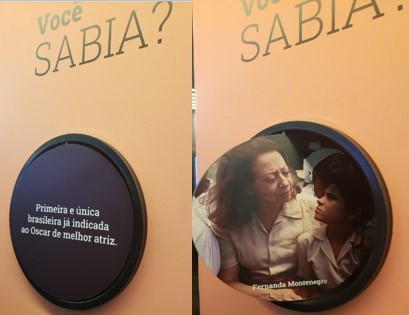

Besides the interactive strategies mentioned above, it is worth mentioning an interactive quiz (Figure 8), with questions about the national cinema and artists, where the audience participates by turning the piece where the question is written.

Such changes in the format of exhibitions enhancing public participation through technological interactivity are also related to the dynamics occurring in the social environment, which emphasise the oral culture, encouraging museums, according to Lumley (1988), to stop being “silent”. For this author, many of these spaces have become hybrid museums, combining screens with interactive tables and devices to establish hyper-realism so that participation prevails over observation, making them more attractive to a wide audience, especially young people.

It is also worth mentioning that these changes taking place in museums towards hybridisation - which according to Canclini (1990/2006), can be defined as sociocultural processes where isolated or separated structures, such as, in this case, the media and the Museum, combine to generate new practices - are driven in contemporary times by the so-called “culture of participation”. According to Jenkins (2015), this culture promotes engagement and audience participation in the relations between content producers and consumers.

4.3. If Only the Cine Embaixador Could Talk...

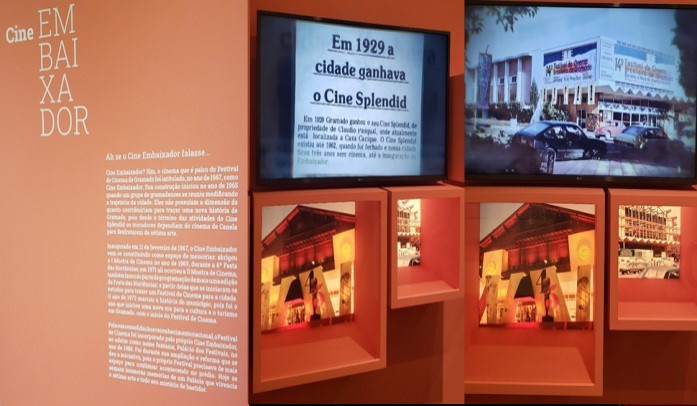

The museographic project also highlights the history of the cinema’s establishment in the city of Gramado, from its inception, with the Cine Splendid, through the Cine Embaixador (Figure 9), and the building of the Palácio dos Festivais.

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 9 Introduction to the history of Cine Embaixador

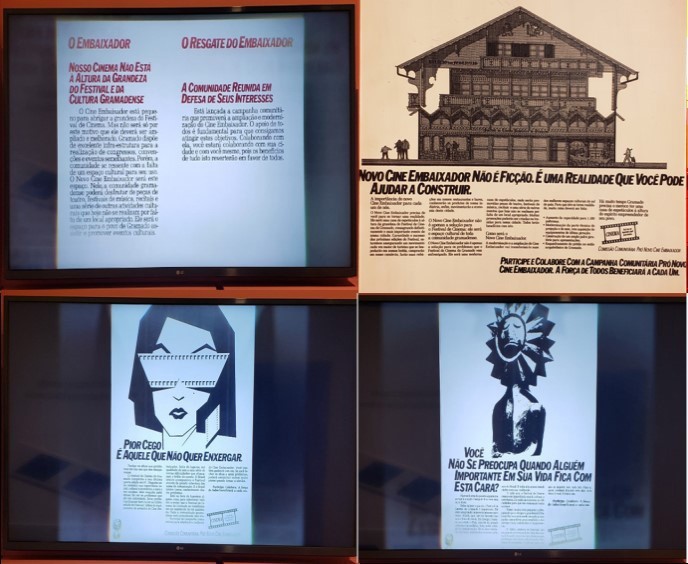

Posters and articles from the local press are also used, showing the appeals of the public authorities of that time, summoning the Gramado community to ensure the event’s continuity (Figure 10).

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 10 Gramado’s public authorities summoning residents to contribute to the renovations of the building where the Film Festival is held

When assessing the narratives written on these posters, under the theoretical lenses of cultural studies, it is possible to infer that through representation strategies - which, according to Hall (2013/2016), involve the use of signs and images to produce and share meanings in culture - the local administration portrays the people of Gramado as supporters of the Festival, described as crucial to the economy of the city of Gramado. Drawing upon Hall (2013), when the author argues that identities are constructed within language through representational strategies, it is possible to conclude that the Museum invites locals to develop a sense of belonging to the film culture in Gramado.

However, the initiatives of the public authorities towards the participation of the local community in the Film Festival are recent. It was only in 1997, during the event’s 34th edition, that an attempt was made to establish a link between the Festival and the community with the project Cinema in the Neighbourhoods, promoting film screenings in the city’s neighbourhoods (Figure 11).

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 11 The year 1997 on the panel about the history of the film festival

It is worth mentioning that the museum’s exhibition design does not include photos or more detailed information to illustrate the moment of the community’s integration into the event. Therefore, upon considering the educational dimensions of this museum, it is possible to conclude that one of its main pedagogical effects is to mobilise the community to support and commit to keeping the Film Festival, which through the residents’ contributions and loans from the City Hall, converted the Cine Embaixador into the Palácio dos Festivais. These messages about the Film Festival, the city of Gramado and its residents that the Museum strives to convey to its visitors are built under the aegis of nostalgic collective memory, which according to Hewison (1999), often subverts negative aspects of the facts to harmonise crises and strengthen a unified identity for the place.

Thus, according to Chagas (2006), museums are political spaces of memories and silences and cannot be considered “innocent” artistic-cultural instances, given that, besides communicating facts of the past, they also “naturalise ways of seeing the world, which legitimate, hierarchize and arrange cultures and identities” (Machado & Zubaran, 2013, p. 137). Hence, the Gramado Film Festival Museum creates narratives that privilege some facts over others, as is the case of the silences about the community’s involvement in constructing the memories of cinema in the city of Gramado.

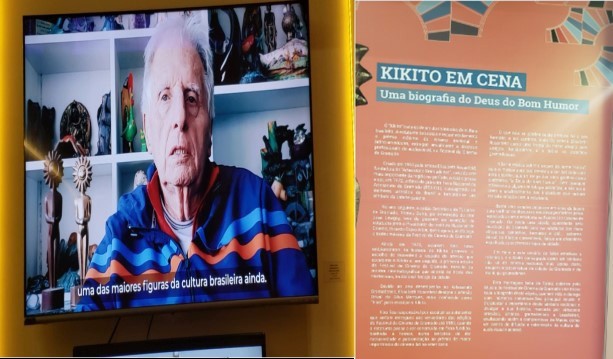

4.4. The Kikito and Its Imprint on the City of Gramado

It is also important to examine one last exhibition design strategy of this museum, concerning Kikito, the highest award of the Film Festival. To introduce the history of the Brazilian Oscar statuette, the Museum screens a video starring the Municipal Secretary of Tourism at the time, Romeu Dutra, and Orival da Silva Marques, who worked in the Artesanato Gramadense with Elisabeth Rosenfeldt. Besides the video, on the wall adjacent to the screen, there is a panel with the biography of the well-known “God of good humour” (Figure 12).

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 12 Video about Kikito and the panel “Kikito on stage”

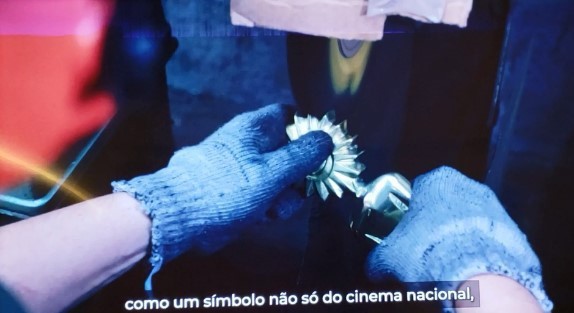

The video narrative highlights the meaning of this sculpture to the Film Festival and the city of Gramado, as illustrated by Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 13 Image taken from the video about the Kikito on display at the Gramado Film Festival Museum

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figure 14 Image taken from the video about the Kikito on display at the Gramado Film Festival Museum, which highlights the importance of this award beyond the scope of cinema

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

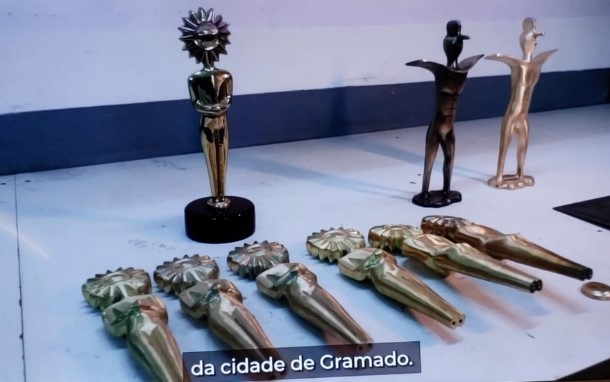

Figura 15 Image taken from the video about the Kikito on display at the Gramado Film Festival Museum, which presents the Kikito as the representative image of the city of Gramado

The video images highlight that the city of Gramado, with the advent of the Film Festival, has built another identity icon, the Kikito. The relevance of the statuette for the municipality is also reinforced by the replicas produced in the traditional factories and chocolate shops that tourists take home. Besides, several of them are around the city, reiterating the idea that Gramado is the city of Kikito, as seen in the following sequence of images (Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18) taken from this video shown at the museum.

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figura 16 Image taken from the video about the Kikito on display at the Gramado Film Festival Museum, which shows the map of this city

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figura 17 Image taken from the video about the Kikito on display at the Gramado Film Festival Museum, which features statues alluding to the awarding of this festival, located at various tourist spots in the city of Gramado

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figura 18 Image taken from the video about the Kikito on display at the Gramado Film Festival Museum, which shows a statue of Kikito in a shopping centre in Gramado

Resuming Lumley’s theory (1988) that the museum can be considered a means of communication and, borrowing Jenkins’ (2006/2009) about the contemporary convergence culture, characterised by the content flow among multiple media, it is possible to observe that the Gramado Film Festival Museum stands out as a media communication vehicle that combines Gramado’s tourist appeal to the Film Festival and, especially, to Kikito. Within this context, it is worth mentioning that the Museum’s logo is represented by a stylised Kikito (Figure 19).

Therefore, in the exhibition narrative created in the Gramado Film Festival Museum, the Kikito is represented as an icon of Gramado and its Film Festival. As such, it also makes it a tourism product, which maximises the city’s tourism potential.

Moreover, it is worth mentioning that in the area of the museum intended to show the artists and directors awarded throughout the event’s five decades, there are other awards besides the Kikito (Figure 20 and Figure 21).

Manoela Barbacovi and Maria Angélica Zubaran

Figura 20 Gramado Film Festival Awards: Gramado City Trophy

Among the trophies presented, the highlight is given to the Gramado City Trophy, which honours people related to the Festival who somehow contributed to the city’s promotion. So, the Festival is linked to local tourism, reiterating the connection between the city, the Film Festival and the Festival Museum, in a kind of synergetic movement, also highlighted in the Bill of Law 057/2015 (Projeto de Lei do Executivo - PLE 042.15), establishing the legal framework for the implementation of this Museum.

Certain representations, such as “the national capital of cinema”, “the city of lights”, and “the city of Kikito”, produced and disseminated by the Film Festival and the Film Museum, are also tourist attractions. They stimulate desires and meet the concept of cultural consumption, proposed by Canclini (1993), seen as “the series of processes of appropriation and use of products in which the symbolic value prevails over the values of use and exchange, or at least the latter are subordinated to the symbolic dimension” (p. 34). So, for the public attending the Festival and visiting the Museum, these cultural and symbolic representations drive many people to visit the city of Gramado.

5. Final Considerations

This analysis, which elected as the object of study the Gramado Film Festival Museum and which aimed at reflecting on the representational strategies used by this Museum to communicate with its visitors, showed that this cultural, artistic instance, besides activating the memories of the Gramado Film Festival, also plays an educational and media role.

Among the representational strategies used by this Museum, it is worth highlighting interactivity and the extensive use of technological resources that make the visitor an active explorer of the museum collection, according to the perspective of the participation culture, where the public is increasingly interacting with content producers.

Moreover, this analysis showed a great cultural connection between the Museum, the Festival and local cultural tourism, producing icons and symbols that interact with and reinforce the vision of the city of Gramado as a tourism destination.

Finally, it is important to highlight that for being part of the theoretical field of cultural studies, this study did not seek to produce comprehensive and unidimensional explanations about the Gramado Film Festival Museum but aimed to draw attention to the importance of its exhibition narratives to the visiting public to enhance the Film Festival and cultural tourism in the city of Gramado.

Referências

Anico, M. (2005). A pós-modernização da cultura: Património e museus na contemporaneidade. Horizontes Antropológicos, 11(23), 71-86. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-71832005000100005 [ Links ]

Brito, Z., & Araújo, B. (2022). SEDAC. In Gramadotur (Ed.), Catálogo do 50º Festival de Cinema de Gramado (p. 17). Ministério do Turismo e Claro. http://gemelo.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/catalogo_50_ web.pdf [ Links ]

Canclini, N. G. (Ed.). (1993). El consumo cultural em México. CNCA. [ Links ]

Canclini, N. G. (2006). Culturas hibridas: Estratégias para entrar e sair da modernidade (H. P. Cintrão & A. R. Lessa, Trads.). EDUSP. (Trabalho original publicado em 1990) [ Links ]

“Cerimônia oficializa Kikito como patrimônio cultural de Gramado”. (2022, 11 de novembro). Câmara Municial de Gramado. https://gramado.rs.leg.br/noticia/visualizar/id/9763/?cerimonia-oficializa-kikitocomo-patrimonio-cultural-de-gramado.html [ Links ]

Chagas, M. S. (2006). Há uma gota de sangue em cada museu: A ótica museológica de Mário de Andrade. Argos. [ Links ]

Coffey, A. (1999). The ethnographic self: Fieldwork and the representation of identity. Sage. [ Links ]

Daros, M. (2008). Grãos: Coletânea histórica. Palotti. [ Links ]

Hall, S. (2013). Quem precisa de identidade. In T. T. Silva (Ed.), Identidade e diferença: A perspectiva dos estudos culturais (pp. 103-112). Vozes. [ Links ]

Hall, S. (2016). Cultura e representação (D. Miranda & W. Oliveira, Trads.). Apicuri. (Trabalho original publicado em 2013) [ Links ]

Hewison, R. (1999). The climate of decline. In D. Boswell & J. Evans (Eds.), Representing the nation: A reader: histories, heritage and museums (pp. 151-162). Routledge. [ Links ]

Hudson, K. (1999). Attempts to define “museum”. In D. Boswell & J. Evans, (Eds.), Representing the nation: A reader: Histories, heritage and museums (pp. 371-379). Routledge. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2009). Cultura da convergência (S. Alexandria, Trad.). Aleph. (Trabalho original publicado em 2006). [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2015). Cultura da conexão: Criando valor e significado por meio da mídia propagável (P. Arnaud, Trad.). Aleph. [ Links ]

Lasanski, D. M. (2004). Introduction. In D. M. Lasanski & B. McLaren (Eds.), Architecture and tourism: Perception, performance and place (pp. 1-14). Berg. [ Links ]

Lei 1738/00 | Lei nº 1738 de 15 de junho de 2000. (2000). http://camara-municipal-do-gramado.jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/407485/lei-1738-00 [ Links ]

Lumley, R. (Ed.). (1988). The museum time-machine. Routledge. [ Links ]

Lupo, B. (2021). Interatividade no espaço expositivo: Os casos do Museu do Futebol e do Museu do Amanhã. In A. Castro, C. Almeida, F. Brito, J. Lira, L. Leão, T. Maretti, & F. Paiva (Eds.), Anais do 1º Seminário de História e Fundamentos da Arquitetura e Urbanismo (pp. 399-412). FAU/USP. [ Links ]

Machado, L., & Zubaran, M. A. (2013). Representações racializadas dos negros nos museus: O que se diz e o que se ensina. In J. R. Mattos (Ed.), Museus e africanidades (pp. 137-156). Adijuc. [ Links ]

Projeto de Lei do Executivo - PLE 042.15. (2015). https://gramado.rs.leg.br/materia/visualizar/ id/3717/?ple-04215.html [ Links ]

Projeto de Lei do Legislativo n.º 028/2022. (2022). https://gramado.ecbsistemas.com/view.php?id=33512&m d5=f62f5f52e3f2eb84a47585136b43e6a2 [ Links ]

Quintans, D. (2008). 35 anos do Festival de Cinema: Memória cultural. ACTG. [ Links ]

Rojek, C., & Urry, J. (1997). Touring cultures: Transformations of travel and theory. Routledge. [ Links ]

Sebrae. (2022, 16 de agosto). Festival de Cinema de Gramado tem grande potencial turístico. https://www. sebrae.com.br/sites/PortalSebrae/artigos/festival-de-cinema-de-gramado-tem-grande-potencialturistico,3c4b2b52ad952810VgnVCM100000d701210aRCRD#:~:text=O%20Festival%20de%20 Gramado%20tamb%C3%A9m,criativa%20ligada%20%C3%A0%20produ%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20audiovisual [ Links ]

Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Gramado. (1987). Gramado, simplesmente Gramado. Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Gramado. [ Links ]

Silva, T. T. (2010). Documentos de identidade: Uma introdução às teorias do currículo. Autêntica. [ Links ]

Souza, S. J., & Lopes, A. E. (2002). Fotografar e narrar: A produção do conhecimento no contexto da escola. Cadernos de Pesquisa, (116), 61-80. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742002000200004 [ Links ]

Steinberg, S. R. (2016). Produzindo múltiplos sentidos - Pesquisa com bricolagem e pedagogias culturais. In K. Saraiva & F. Marcello (Eds.), Estudos culturais e educação: Desafios atuais (pp. 211-243). Editora Ulbra. [ Links ]

Steinberg, S. R., & Kincheloe, J. (Eds.). (2004). Cultura infantil: A construção corporativa da infância (2.ª ed.; G. E. J. Bricio, Trad.). Civilização Brasileira. (Trabalho original publicado em 1997). [ Links ]

Urry, J. (2001). O olhar do turista: Lazer e viagens nas sociedades contemporâneas (3.ª ed.). Studio Nobel. [ Links ]

Wortmann, M. L. C., Costa, M. V., & Silveira, R. M. H. (2015). Sobre a emergência e a expansão dos estudos culturais em educação no Brasil. Educação, 38(1), 32-48. https://doi.org/10.15448/1981-2582.2015.1.18441 [ Links ]

Received: October 31, 2022; Accepted: January 20, 2023

texto en

texto en