Art is one of the domains in which, in recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on the need for re-politicizing life - Marina Garcés, Un Mundo Común, p. 68

It’s a visual world, and people respond to visuals. - Joe Sacco, But I Like It, p. 107

Feminism is a collective adventure for women, men, and everyone else, a revolution well underway. A worldview. A choice. - Virginie Despentes, King Kong Theory, p. 137

1. The Emergence of Social Comics

In Spain, the synergy of the emergence of socially engaged graphic narratives, known as “comic social” (Gallardo & Roca, 2009), the rise of collective forms of physical and virtual social engagement during the 15M Indignados protests, and the irruption of feminist activism have created a fertile ground for new forms of artivism. The publication of Paco Roca’s (2007) Arrugas (Wrinkles), Miguel Gallardo’s María y Yo (Mary and I; 2007), and Cristina Durán and Miguel Ángel Giner Bou’s (2009) Una Posibilidad Entre Mil (One Chance in a Thousand) demonstrated that the sequential art could be a powerful vehicle to discuss sensitive subjects such as disability, aging, and mental deterioration, and opened the way for innovative visual-verbal narratives and illustrations that mobilize the embodied nature of the ninth art to draw attention to neglected social problems. In a politically engaged vein, they created new kinds of graphic narratives that give visibility to traditionally silenced subjects and minorities that do not fit the ableist and productivist mold promoted by neoliberal biopolitical regimes. At a time characterized by “a dizzying re-politicization of Spanish social life” (Herrero, 2019, p. 127), increased social mobilizations, powerful feminist activism, and a vibrant graphic and illustration sector, the gendered aspect of social and political struggles was reflected in sequential as well as single-panel illustrations. From daily newspapers to satirical magazines to online publications, the world of graphic narratives and political cartoons has enjoyed renewed vibrancy, becoming a valuable tool for activism.

As such, it has heralded new forms of social interventions that reflect the spirit of grassroots organizations, whose origin can be traced to the 15M Indignados movements that transformed the Spanish political and social landscape1. While growing social mobilizations advocated for communal forms of activism, configuring an “ecosystem of the commons”, as Palmar Álvarez Blanco (2021, p. 31) terms it, women graphic illustrators were quick to respond to right-wing attempts to curtail hard-earned reproductive rights. When, in December 2013, the leading conservative Spanish party, Partido Popular (PP), crowned its unrelenting efforts to curtail gender equality by passing the most restrictive abortion bill in Spanish democratic history, the Spanish collective Artistas de Cómic launched “Wombastic, imágenes por la libertad de expresión” (Wombastic, images for freedom of expression), a Tumblr-based initiative that called for the submission of illustrations and graphic strips to fight back. Graphic artists demonstrated the power of an “embodied” narrative form like comics and graphic humor (Szép, 2020, p. 2) by organizing to defend women’s rights, sanctioned by the 2010 organic law decriminalizing abortion2. In doing so, they joined hands with numerous feminist organizations whose public protests shook the country3. Mirroring the climate of the intense social mobilizations known as the Indignados or 15M movement, which changed the Spanish social and political landscape in 2011, feminist collectives combined to defend hard-earned reproductive rights.

Focusing on the visual motifs, iconographies, and visual metaphors (El Refaie, 2019) employed in the cartoons and strips uploaded to Wombastic, I propose to analyze how art activism can be mobilized “with the objective of achieving social and or political change” (Serafini, 2018, p. 3). In doing so, I place this initiative within a discursive context that posits a renewed politicization of the body (Garcés, 2013) as an antipatriarchal and anticapitalistic alternative to neoconservative attacks on women’s bodies. In my biopolitical analysis, I provide a brief genealogy of feminist graphic humor and art activism in the fight for reproductive rights, paying particular attention to the iconography of the womb as a site of political intervention in a country in which women’s relationship with reproduction continues to be fraught with difficulties.

Recognized as an important artistic intervention and included in the Museo Reina Sofía’s recent exposition “¡Mujercitas de Todo el Mundo, Uníos! Autoras de Cómic Adulto (1967-1993)” (Little Women Around the World, Unite! Adult Comic Book Authors[19671993])4, Wombastic has been analyzed as a response to a form of State-sanctioned gender-based violence. In her seminal article “Wombastic, la Batalla Gráfica por la Reapropiación del Cuerpo Femenino Frente a la Amenaza de Gallardón” (Wombastic, the Graphic Battle for the Reappropriation of the Female Body in the Face of the Threat of Gallardón), María Márquez López (2018) provides a detailed study of the abortion bill’s discursive qualities as well as an in-depth reading of three important images that “highlight the keys to the infringement of rights sought by former minister Gallardón” (p. 278). Instead, I place Wombastic within a genealogy of feminist artistic interventions as well as social movements originating in the late Franco period - when illustrators such as Núria Pompeia, Montse Clavé, and Elsa Plaza, among others, created posters, illustrations, and visual narratives in support of women’s reproductive rights. Aware of the ways in which graphic humor has proved to be an influential ally in political struggles5, I draw attention to the socio-cultural context in which a collective initiative such as Wombastic emerged, underlining the visual aspects of a corpus of images that mobilizes the body as a site of political activism while exposing the paradoxical rhetoric of Spanish former Minister of Justice Alberto Ruiz Gallardón. In doing so, I explore the ways in which cyberactivism and artivism successfully join hands in fighting back against right-wing legislators’ attempts to turn women’s bodies into battlefields in order to reinstate heteropatriarchal gender norms.

2. Reclaiming a Feminist Genealogy in Comics and Illustrations

Inspired by the French Collectif des Créatrices de Bande Dessinée Contre le Sexism, the collective Autoras de Cómic was created to support gender equality in a predominantly male medium, to support women illustrators, and to recover a forgotten feminist lineage6. In line with their effort to foster a more equitable space in the publication industry and to fight structural sexism that marginalized and invisibilized women artists, they promoted initiatives to bring to light the rich genealogy of Spanish illustrators. Their feminist intervention revitalized a tradition dating back to the 1970s and 80s, when “the naked female body acquires strong political meanings and comes to symbolize abstract ideas such as democracy and freedom” (Garbayo Maeztu, 2016, p. 13). In an attempt to subvert the androcentric gaze that characterized graphic narratives and feminist political cartoons of the Transition period, feminist artists and illustrators, such as Núria Pompeia, Montse Clavé, Elsa Plaza, and Marika Vila, among others, problematized the corporeal aspect of the comic medium, in which the body was held prisoner to the male gaze. Fighting for women’s empowerment, they tried to break free of the prevailing ways of depicting women as objects of male desire while attempting to develop new pictorial languages that could put an end to what comics illustrator and theorist Marika Vila (2021) has termed “el cuerpo okupado” (the occupied body). Freeing the female body from the effects of a male symbolic order, several illustrators attempted to display women’s agency while exposing the need for key reproductive rights.

In their political cartoons and illustrations, which appeared in political posters, underground and feminist magazines (such as Butifarra, Vindicación Feminista, and Dones en Lluita), and political publications such as Triunfo, the Catalan illustrator Núria Pompeia carried out an intense campaign to support much-needed social rights for women, who, under Franco’s legislation, were not only forbidden from accessing contraception, but were kept under male tutelage till the age of 25 if unmarried or under marital control if they were wedded. With her impactful though seemingly simple style, Pompeia spotlighted the adverse side effects of the Francoist rhetoric that chained women to reproduction. In her books, in particular in 9Maternasis (1967), Y Fueron Felices Comiendo Perdices… (And They Were Happy Eating Partridges...; 1970), and Mujercitas (Little Women; 1977) as well as in her illustrations accompanying Eugeni Castell’s medical book El Derecho a la Contracepción (The Right to Contraception; 1978), she used simple black and white lines to display the need for sexual education and legalized contraception. In the many cartoons interspersed throughout the book, she sought to expose the effects of unplanned pregnancies on middle-class women. Through quickly drafted outlines, the main character, a young, unremarkable woman, reveals her surprise and incredulity at the proliferation of newborn children surrounding her. In a visual composition reminiscent of Jonathan Swift’s lilliputians, the woman is immobilized by the newborns, who continue to erupt out of her body. Throughout this book, as well as in political posters and illustrations, Pompeia never ceased to expose women’s contentious relationship with mandatory reproduction. As a mother of five, she exposed the essentialistic views that held women hostage to domesticity and motherhood, thus supporting the notion that reproduction needed to be chosen freely, a theme that made frequent headlines in the years leading up to Spanish democracy.

While the road to the decriminalization of contraception and abortion was a long and complicated one in Spain, as right-wing and religious organizations such as Opus Dei exercised pressure to limit women’s self-determination in reproductive matters, Gallardón’s attempt to turn back the clock on abortion rights was met with significant resistance and massive mobilizations. Among them, Wombastic was intended as a “graphic platform and poster support for the next manifestations and mobilizations against a retrograde abortion law” (“¿Qué Es Wombastic?”, 2014, para. 2). Launched in support of initiatives aiming to defend the 2010 abortion law against conservative attacks, this kind of art protest reflects the social conditions of Spanish women at a time of increased precarization. As founders Susanna Martín and Clara Soriano emphasize: “Wombastic arises at a time in which we, like many people, especially women, are living (badly), in which financial support, salaries and even fundamental rights such as the right to decide upon our own bodies are being scaled down” (Gràffica, 2014, para. 3). A profound economic crisis had plunged the country into a severe recession, and the effects of the austerity measures implemented since 2010 resulted in a deeply antimaternal climate. Specifically, by December 2013, Spanish society had already witnessed overall impoverishment, a high unemployment rate among both men and women, a lack of stable employment prospects, cuts to the welfare state, a paucity of state-funded daycare centers, the overall sense of precarization of life expectancy, and the unrelenting erosion of hard-earned rights. Amidst a series of misogynistic reforms that affected women more severely than men, the proverbial last straw was the curtailing of women’s access to the voluntary interruption of pregnancy.

3. Mobilizing Feminist Iconography

Graphic artists and illustrators enthusiastically responded to the call for submissions, exploiting the expressive affordances of illustrations - with their mix of visualverbal elements - to provide a critical intervention in support of online and in-person mobilizations. Their feminist political illustrations rely on specific iconographic choices that hark back to a feminist tradition that is chromatically characterized by the use of purple, challenging the paternalistic language of the anti-abortion bill. In order to subvert the paternalistic rhetoric and pseudo-logic of the Bill of Organic Law for the Protection of the Life of the Conceived and the Rights of the Pregnant Woman (Ministerio de Justicia, 2013), many of the images articulate a counterdiscourse to dismantle state intervention in reproductive matters (Mayans & Vacas, 2018, pp. 22-39). As a result, most images reflect “broader debates within feminist literatures regarding ‘choice’, agency, and autonomy over one’s body” (Jackson & Valentine, 2017, p. 222). Confronting the sense of entrapment elicited by the proposed State intervention in women’s reproductive health and rights, two of the most common responses oscillate between an exposition of the violence of State-mandated reproduction and an empowered reclaiming of one’s own body. While the former is visually signified by the use of chains, handcuffs, and restraining devices, the latter articulates a counterdiscourse by turning female anatomy into a canvas onto which the right to self-determination finds verbal expression.

Due to the lack of sequentiality in single-panel illustrations, the economy of signification is particularly stringent. Since “a picture has to say it all” (Barbieri, 1991/2013, p. 22), allusions to Gallardón and his bill of law are often present using his face, which is frequently satirized or caricatured. Creating impactful images that speak directly to the audience, these visual compositions provide a critical commentary on the political situation in Spain and the possible consequences of the proposed legislative changes. As is to be expected, the over 250 images mix a variety of recognizable feminist signs, such as the clenched fist enclosed in the women’s symbol as a reference to feminist struggles for gender equality and empowerment. The image of the womb, as we will see in this article, is also featured in many of the illustrations, together with religious iconography, revisited in humorous and radical tones.

Considering the fact that, as Daniele Barbieri (1991/2013) indicates, unlike comics, a single illustration “should give as much commentary information as possible” (p. 22), many illustrators employ stylized images and basic colors. While others include more elaborate pictorial images, some tend to be very direct in their use of visual references with short, direct punchlines that reiterate women’s rights to choose. “I decide” is thus displayed as a commentary on a plethora of images in which female anatomy is reinterpreted in creative ways. Relying on “the essentially embodied nature of both drawing and reading comics” (Szép, 2020, p. 2) and illustrations, many contributors reclaim and reshape images of the uterus.

In keeping with the spirit of social justice that fueled the creation of the association7, a growing number of people joyfully shared their creativity in an attempt to block a draft law that, if passed, would have turned the clock back 30 years on reproductive rights. Their initiative made an impact. Because the fight for self-determination in reproductive matters, as well as ownership of women’s bodies, had been key issues of Spanish feminist movements since the 1970s, an overwhelmingly large segment of the democratic society firmly rejected the attempts to increase State control in reproductive matters.

In their illustrations, the artists recall an iconography steeped in philosophical and feminist traditions. In dialogue with the contemporary theorization of the political nature of the body, they foreground the power of images as a vehicle for political action. In this kind of collective mobilization, authorship of the posters becomes secondary to a collaborative initiative that allows all contributions to be freely downloaded, shared, printed, and circulated in the physical and virtual squares in Spain and around the world. Against the neoliberal repressive policies that over the years have extended from the productive to the reproductive spheres of society, Wombastic urges “an emotional choreography”, that is, “the construction of an emotional narration to sustain their gathering in the public space” (Gerbaudo, 2012, p. 12), thus encouraging forms of art activism aimed at fighting against restrictive government intervention in reproductive matters.

4. Reclaiming a Womb of One’s Own

Rooted in the spirit of collective activism, Wombastic reflected the Butlerian notion that “for politics to take place, the body must appear” (Butler, 2011, para. 5) and thus participated in a series of feminist initiatives that aimed to support offline protests in Spanish streets and squares. In particular, El Tren de la Libertad, with its slogan “I decide”, inspired many posters created for Wombastic. Organized by the feminist collective Les Comadres in the northern town of Gijón, it created a bridge between seasoned and young activists by bringing thousands of women and men from all corners of Spain to the doors of the Congress of Deputies in Madrid on February 1, 2014, to protest the new anti-abortion bill8.

Problematizing the notion according to which tota mulier in utero (woman is a womb), Wombastic signals an attempt to reclaim the womb as a site of political action against misogyny and patriarchy. As a result, it represents female anatomy in such a way as to send clear messages and mobilize citizens in protests. The posters, uploaded to the online platform within days of the campaign’s launch, draw attention to the corporality of women’s bodies in an attempt to reclaim ownership of the uterus as a space of feminist expression. In doing so, they confront a long misogynistic tradition that assigns a fundamental role in women’s existence to this organ.

In intertextual dialogue with a corpus of philosophical, medical, and psychoanalytic writings that interpret the uterus as a key determinant of women’s physical and mental health, the contributors to Wombastic reshape its meaning in myriad forms. While some artists reinterpret medical representations, thus subverting the scientific gaze, others adhere to authoritative representations of women’s inner organs only to deploy them against patriarchal norms. Through various visual metaphors, numerous artists challenge the idea that anatomy is a destiny predicated upon subordination to repressive State-mandated reproductive laws. Inspired by Femen’s protests, some posters envision women’s bodies as canvases onto which their authors can project their own subject position, thus challenging the male gaze that objectifies them and asserting their rights to self-determination and self-representation.

In line with the title of the Tumblr project, many contributors thus focus on the womb in an attempt to reconceptualize women’s anatomy. Working within a predominantly binary conception of gender differentiation, the images uploaded to this platform enter into dialogue with one another and reflect a variety of feminist stances regarding the female body. As will become evident through a close reading of some of these illustrations, they turn to bright colors, oscillating between a joyful reappropriation of women’s sexuality and a denunciation of the impending dangers of a repressive bill of law. As María Márquez López (2018) underlines, “the government aimed to deprive gestating women of their voices so that they would depend exclusively on medical tutelage” (p. 279). Against the wording of the new anti-abortion bill, which grants rights to the unborn at the expense of the gestating woman, many artists decry Gallardón’s attempt to degrade women to the role of mere incubators, whose task is to “produce” children for the nation, as it had been under the Franco dictatorship when control over women’s sexuality was particularly stringent. Maite Garbayo Maeztu (2016) notes, “the regime knows that controlling women’s bodies and sexuality is the necessary mechanism to ensure that women continue with their role as biological and symbolic reproducers of the nation” (p. 11). Given the long shadows of the Francoist regime, reproduction has been a vexing issue in Spain, one that feminists considered particularly problematic given that regime’s identification of women with motherhood.

In response to a long and painful history of control over women’s bodies, Wombastic’s images challenge deep-rooted ideas concerning women’s own corporeal realities, rejecting the notion that the female body should be considered a potentially reproductive one. In order to convey this message, they turn to various visual metaphors that “are more directly inspired by our physical experience” (El Refaie, 2019, p. 7). The images stored on its website often employ a chromatic palette of pink and purple to reveal tensions with a long history of thought for which “the specificities of the female body, its particular nature and bodily cycles-menstruation, pregnancy, maternity, lactation, etc. - are ( … ) regarded as a limitation on women’s access to the rights and privileges patriarchal culture accord to men” (Grosz, 1994, p. 15). Reflecting the suspicion with which egalitarian feminists responded to French and Italian feminism of difference, many artists involved in this initiative mobilize ideas that aim to dispel the outdated equation of femininity with maternity.

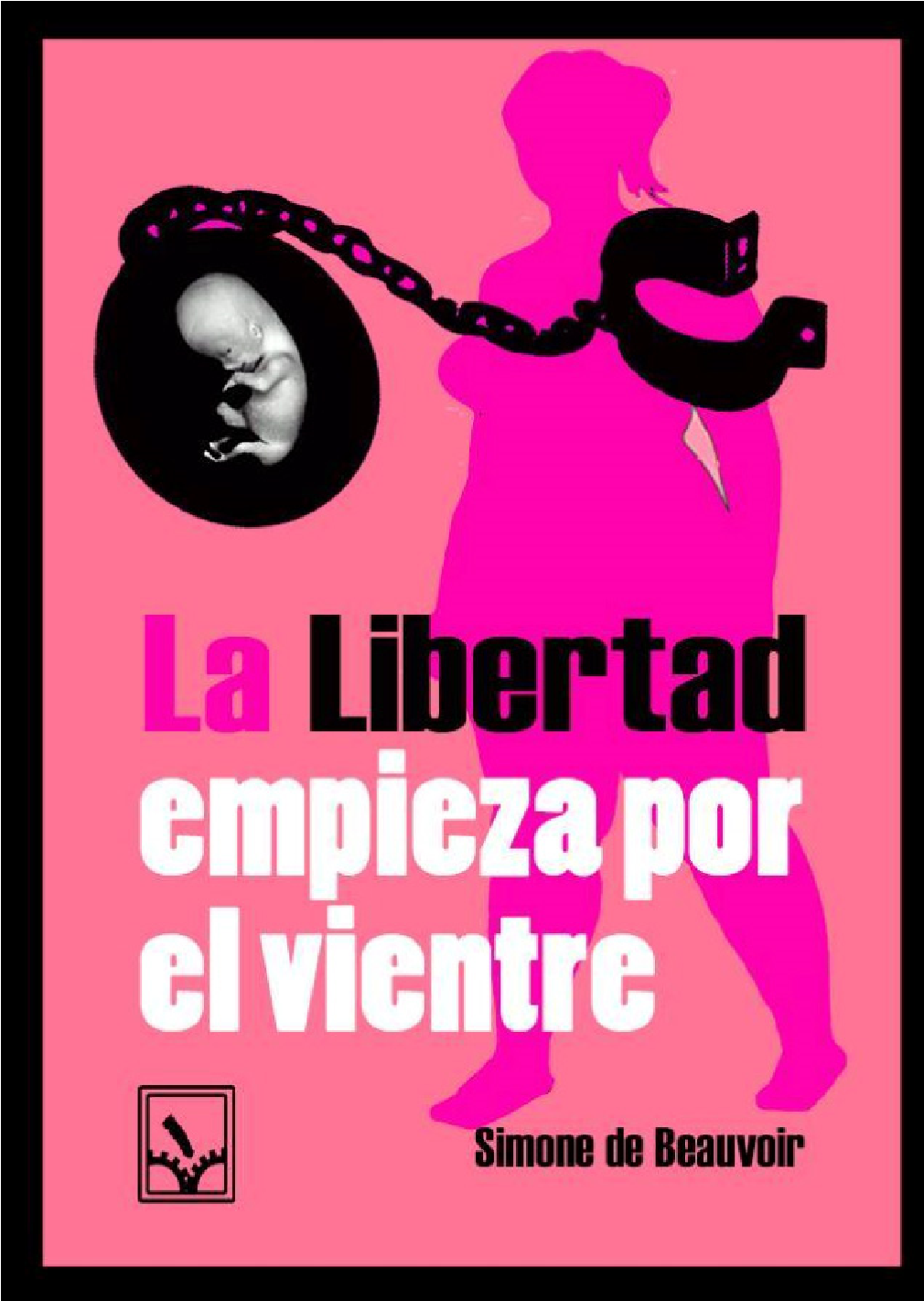

As in the 1970s and 80s protests, several artists insist that reproduction should be a freely chosen option for women, not an imposition antithetical to women’s life goals. As in the famous distinction made popular by Adrienne Rich between motherhood and mothering, any form of mothering - according to Spanish activists - should be the result of a personal decision, not of a State-sanctioned obligation. Moreover, in opposition to Simone de Beauvoir’s notion that motherhood is a castrating role antithetical to any kind of emancipatory discourse, artists like Paulapé (2014) support a pro-choice message with an image that shows a pregnant woman saying, “being a mother is a right, not an obligation”. Allusions to de Beauvoir’s antimaternal stance appear in what looks like a book cover featuring the image of a fetus inside a black bubble linked by a chain to a handcuff, which stands beside the silhouette of a faceless gestating woman (Figure 1). Surmounted by the quote, “freedom starts in the uterus”, attributed to the French thinker, it points to the need to make reproduction a choice, an idea signified by the open handcuff.

Source. From Wombastic, by Manada de Lobxs, 2014, March 2. (https://wombastic.tumblr.com/post/78322849138/manada-de-lobxs)

Figure 1 La Libertad empieza por el vientre

In opposition to a regime in which women are deprived of a way out of the imperative to reproduce, the image, signed by Manada de Lobxs, rejects a punitive, disciplinatory, and alienating relationship with reproduction.

Given the influence of the Catholic Church on Gallardón’s attempts to change the abortion law, references to religious imagery are intertwined with representations of women’s reproductive organs in several feminist posters. As is to be expected, in some of them, the crucifix, rosary beads, and other religious symbols are deployed to challenge Church dogmas towards sexuality and reproduction. Among the over 250 images uploaded to the platform, the well-known slogan “get your rosary out of our ovaries” accompanies several images that utilize a string of beads to configure stylized drawings of women’s reproductive apparatus9.

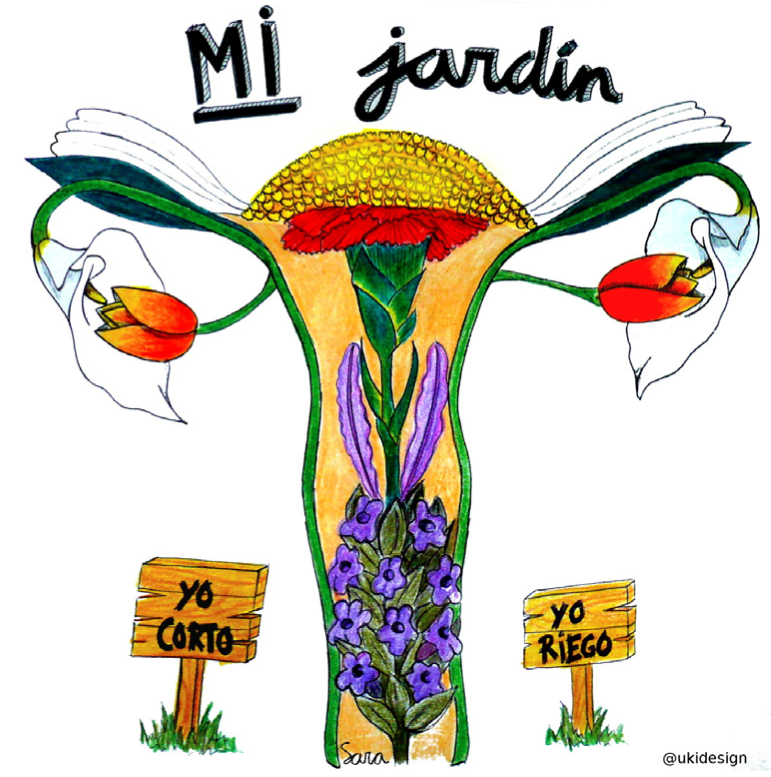

Reclaiming the uterus as a space of her own, Sara Catalina turns the womb into a flowery creation that playfully asserts its own rights (Figure 2). In a vibrantly colored pencil crayon illustration, floral imagery is deployed to assert women’s rights over their own reproductive organs. Making the uterus bloom, the artist visually underscores women’s control of their own fertility. In opposition to the biblical and medieval trope of the hortus conclusus, which enclosed female sexuality within a repressive male social order, Catalina’s image, titled “Mi Jardín” (My Garden), mobilizes fecundity and reproduction as feminist attributes.

Source. From Wombastic, by Sara Catalina, 2014, February 11. (https://wombastic.tumblr.com/post/76315543982/sara-catalina)

Figure 2 Mi jardín

The joyful colors of the floral composition, comprising calas, tulips, carnations, and violets, support the notion that female anatomy does not sentence women to a life of drudgery. At the same time, resorting to vivid shades of yellow, red, and purple recalls the colors of the Republican flag, thus building an ideological bridge with the short-lived left-wing progressive government of 1931-1936 that the Francoist troops had overturned during the Civil War. Whereas during the Second Republic, women achieved unprecedented legal rights, including the right to vote, divorce, and have an abortion, Francoism placed women under male jurisdiction, sanctioning motherhood as women’s natural destiny in the shadow of repressive discourses darkened by the most reactionary parts of the Catholic hierarchy10. The image is accompanied by two small wooden signs asserting women’s right to either prune their own gardens or provide them with necessary nutrients: reading “I cut” and “I water”, the signs summarize women’s autonomy in reproductive matters. The flowery composition overturns the notion that anatomy is a cruel destiny subject to patriarchal laws.

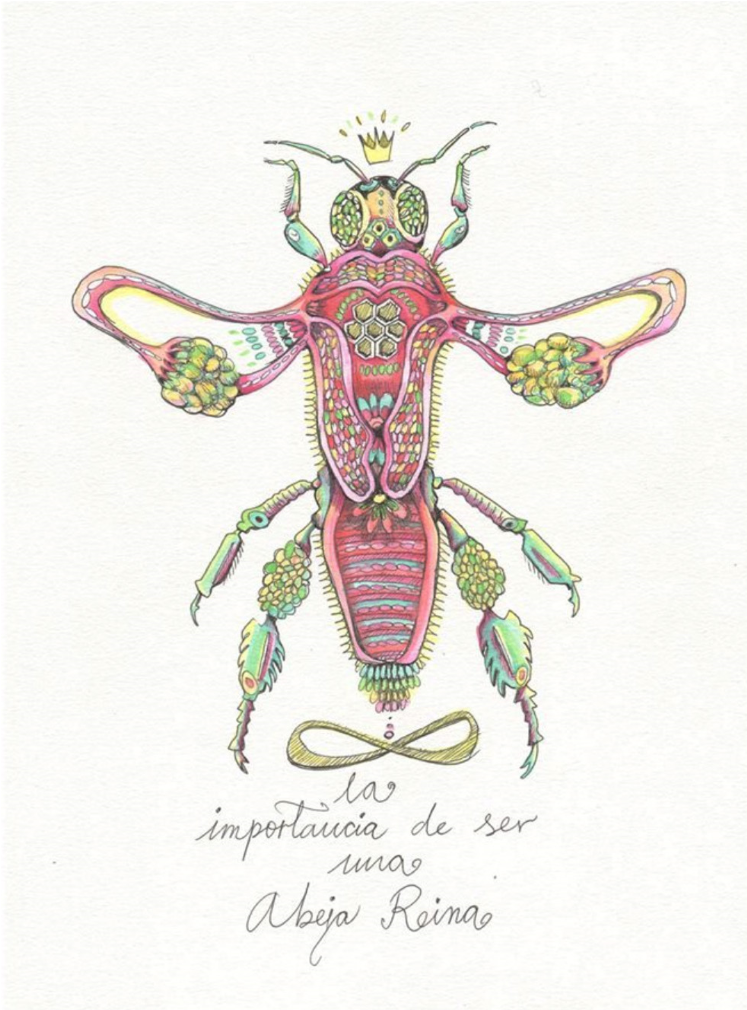

Undoing the misogynistic undertones of the “queen bee syndrome”, which symbolizes women’s lack of empathy in professional settings, Alba Blanco’s (2014) vignette is titled “The Importance of Being a Queen Bee” (Figure 3).

Source. From Wombastic, by Alba Blanco, 2014, February 12. (https://wombastic.tumblr.com/post/76411132274/alba-blanco)

Figure 3 La importancia de ser una abeja reina

The vignette features a pastel pink and green crayon pencil drawing of a queen bee whose wings are shaped in the form of ovaries, while the lower body of the insect clearly resembles the female reproductive organs. The metamorphosis of women’s anatomy plays on the function of this insect, whose sole role in the hive is reproduction. The drawing, merging the social and biological functions attributed to this creature, foregrounds women’s creativity by reappropriating a figure whose attributes seem antithetical to women’s liberation. The metamorphosis of women’s anatomy with shades of pink, light green, yellow, and aqua blue creates a sense of serenity more akin to Hallmark cards than radical feminist imagery. Conveyed by this harmony is the drawing’s message that women will be their own queen bees and fly away from normative reproductive imperatives. Reconceptualized and reappropriated for a feminist cause, the “queen bee” trope aims to undo the insect’s negative connotations while fighting against the Kafkaesque metamorphosis that Gallardón’s anti-abortion bill seeks to impose upon women.

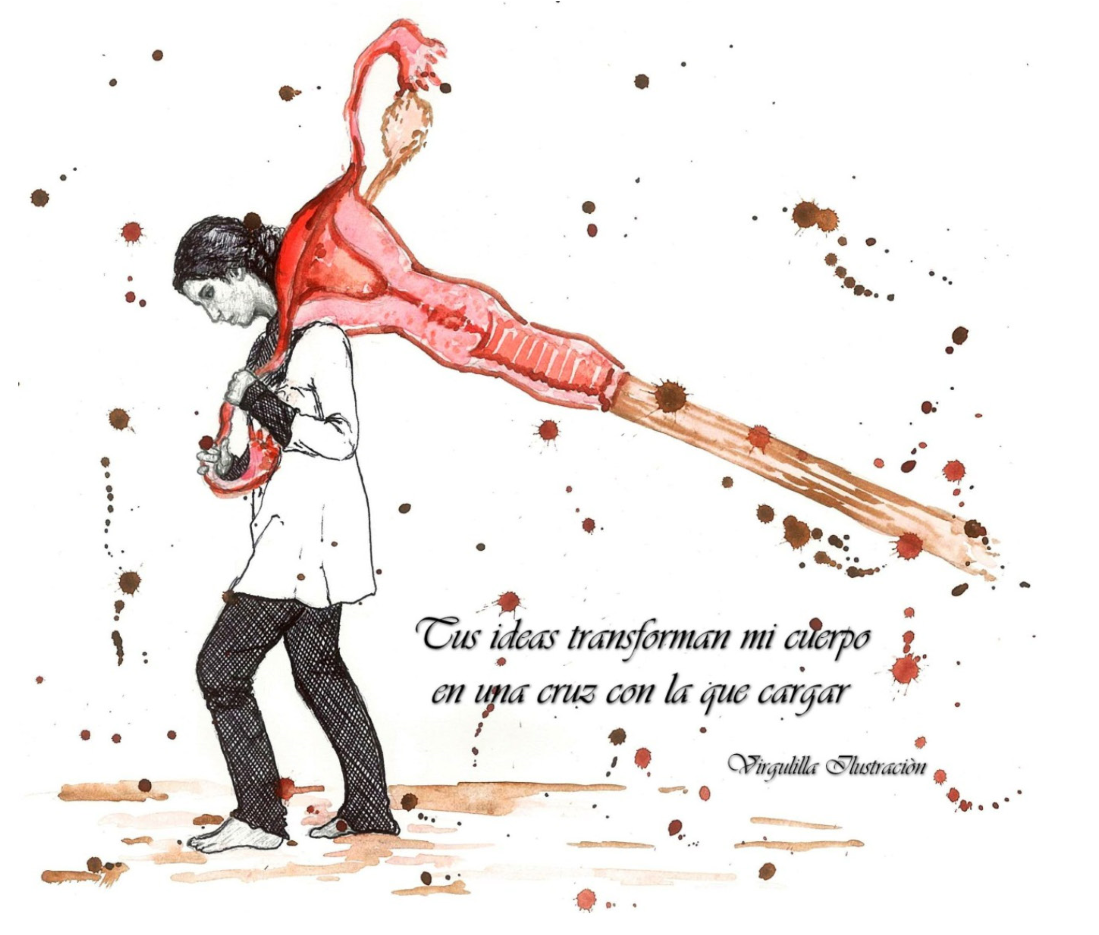

Drawing attention to the dire effects of Church dogma on women’s existence, Virgulilla Ilustración (2014; Figure 4) configures a somber image that showcases the weight of religious doctrine in constricting women’s lives.

Source. From Wombastic, by Virgulilla Ilustración, 2014, February 12. (https://wombastic.tumblr.com/post/76466034834/virgulilla-ilustraci%C3%B3n)

Figure 4 Without title

Presenting a woman who, much like a penitent during a Holy Week procession, drags a heavy crucifix shaped like a bloody uterus, the image evokes the Catholic teaching that all human beings have to bear their own crosses. In doing so, the poster shows how, in the hands of right-wing politicians, women’s biology becomes the site of Churchmandated suffering. As the caption of the image points out, Gallardón’s political views stigmatize women: “your ideas transform my body into a cross that I have to carry”. It is against rhetoric that aims to subjugate women and make them hostages of the State and of misogynistic religious thinking that many of Wombastic’s artists express their dissent.

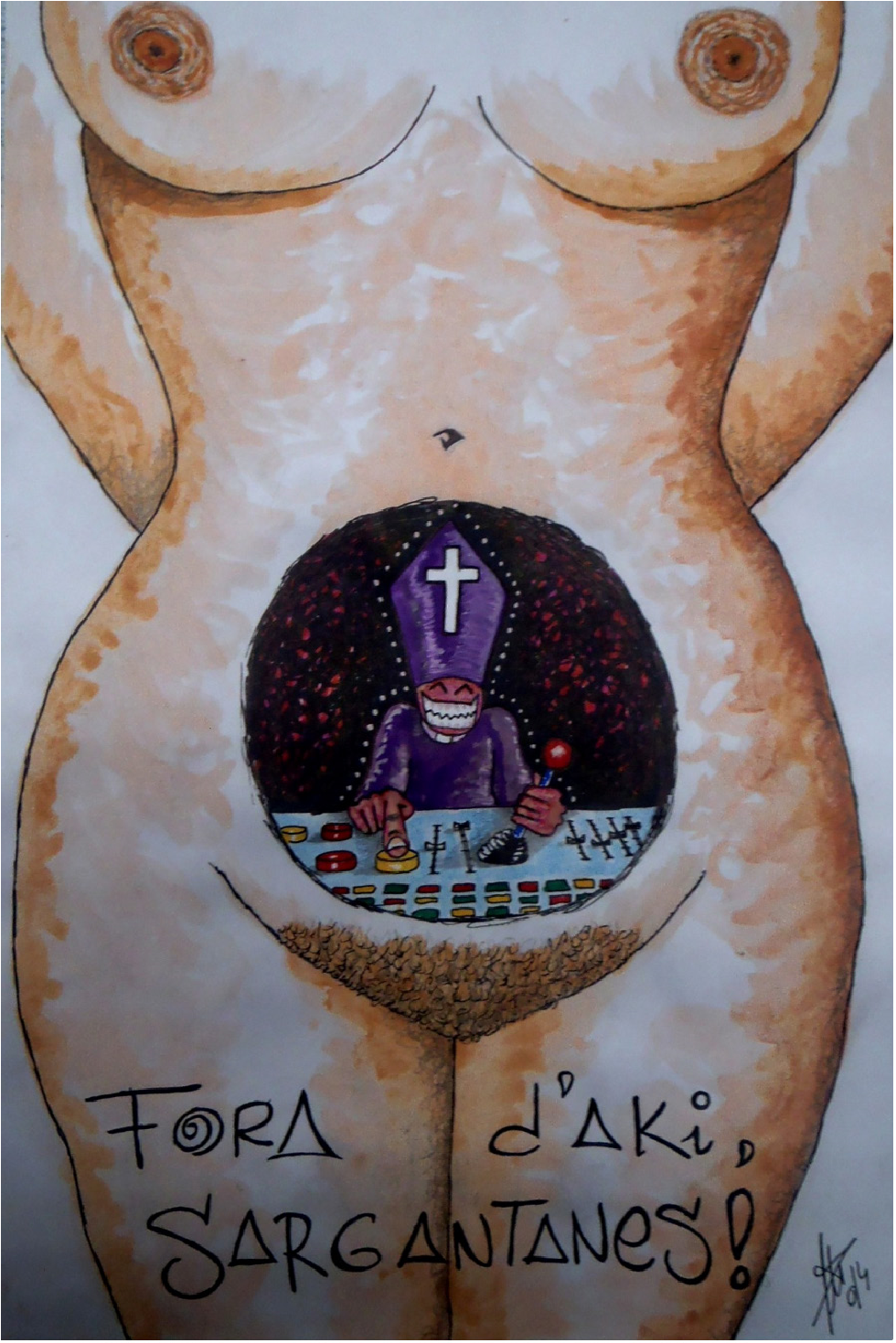

Creative responses to the role of the ecclesiastical hierarchy in the crusade against women’s rights can be seen in several of the posters uploaded onto the platform in February, a month in which feminist protests were more intense. Among them, one of the most striking images shows a young, headless, naked female torso that has been hollowed out, as in a medical atlas (Figure 5).

Source. From Wombastic, by Kali Motxo Amb Gel, 2014, February 15. (https:// wombastic.tumblr.com/post/76727373367/kali-motxo-amb-gel)

Figure 5 Without title

The image makes the inside of the woman visible, recalling canonical texts of obstetrical science. Nonetheless, as if in a work of dystopian science fiction, the woman’s womb is occupied by technology at the service of the Church. Rather than revealing a fetus or the inner organs, the image displays the uncanny scene of a bishop extending his hands over a complex control panel as if commanding a spaceship. With a devious grin, the high prelate intends to push a button with his right hand while clutching a joystick, a phallic symbol, with his left. Lacking a phallus himself (the image implies), the prelate derives pleasure merely from directing the woman’s body to function according to his will. Alluding to the medical gaze that heralded the emergence of a new form of control over reproduction, the image stages the return of ecclesiastical power over women’s bodies.

While the display of the female torso creates a link with the Femen protests that were being orchestrated in several Spanish churches at the time, the presence of a bishop with a miter programming the functioning of a woman’s uterus clearly acknowledges the regressive influence that the Church prelates were aiming to achieve. Disturbing and forceful, this work, by a Catalan artist identified as Kali Motxo Amb Gel (2014), is accompanied by the clear, direct message, “get out of here, lizards”. Against the creeping power of the Church, with its will to dominate and shape women’s lives, imprisoning and condemning them to procreate against their will, several artists’ slogans, drawn onto women’s abdomens, convey counter-hegemonic messages against the appropriation of women’s generative power.

In the same vein, many artists superimposed images of women’s reproductive organs onto Gallardón’s face to draw attention to how the minister of Justice attempted to silence women. Mixing caricaturesque representations and parodic imagery, these powerful pictures “hit you, touch deep nerves” (Olías, 2014, para. 1), as graphic artist Susanna Martín points out11. Displayed on the streets, shared over the internet, and pasted onto street lamps and city walls, they sent strong messages against an anachronistic legal reform that Spanish society had rejected. A large segment of the population had taken to the streets to demonstrate against waves of budget cuts that had left the Spanish middle class largely impoverished; such people were unwilling to cede further rights. Several posters, engaging that widespread sentiment, display clearly recognizable references to current events, especially the anti-life policies supported by the PP. In “Backstabbing in the PP”, the singlepanel visual narratives demonstrate how xenophobia goes hand in hand with concrete attempts to eliminate women’s rights to self-determination in reproductive matters (Jesús AG, 2014). In fact, as Rosalyn Diprose and Ewa Ziarek (2018) have argued, even in liberal democracies, xenophobic sentiments often accompany politics aiming to control women’s reproductive rights. The policies put in place by this right-wing Government amounted to “attempts to restrict women’s reproductive self-determination” that were concomitant with “the intensification of hostility towards immigrants and refugees” (Diprose & Ziarek, 2018, p. 1). The same rhetoric of protection employed in the anti-abortion bill is employed in the anti-immigrant bill, which invokes citizens’ safety in order to demonize immigration. Exposing the vacuity of Gallardón’s pro-life stance, the poster presents an imaginary dialogue between former Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and his minister of Justice. This dialogue reveals the necropolitics of their right-wing Government in deciding which lives are worth saving and which are deemed dispensable. From their conversation, we learn that one abortion has been provoked by the institutional forces in charge of patrolling the border crossing in the city of Melilla, a Spanish territory in northern Africa where razor wire fences are installed to prevent people from gaining entrance to Europe (Jesús AG, 2014). A woman has lost her unborn child while trying to cross that border. Reflecting Mbembe’s (2019) theorization concerning the death practices stipulating “who may live and who must die”, the image exposes the false defense of human life inherent in Spain’s anti-immigration laws.

Extremely critical of the deceitful rhetoric of support for human life expressed in the anti-abortion bill are graphic artists Cristina Duran and Miguel Giner Bou (2014), known for their socially engaged comics. Authors of the graphic memoir Una Posibilidad Entre Mil, which narrates their daughter Laia’s struggles to survive cerebral palsy, they know intimately the challenges of bringing up a child affected by a serious medical condition that requires constant attention and daily physical therapy in a country that has systematically cut funds for healthcare and disability. With their well-known style, made up of thick, almost geometrical lines, Cristina and Miguel deliver a powerful image with strong autobiographical overtones in which a child in a wheelchair wearing an oxygen mask is aided by a caregiving figure, who resembles Cristina herself. Whereas the graphic novel that chronicles Laia’s first years of life leaves off when Laia is still a toddler - making progress in her journey towards regaining her mobility, diminished by the stroke she suffered hours after she was born - this image shows a much older child, and thus her wheelchair is much heavier (Figure 6).

Source. From Wombastic, by Cristina Duran/GinerBou, 2014, February 1. (https://wombastic.tumblr.com/post/75250204757/cristinaduranginerbou)

Figure 6 Without title

The mother-daughter image is accompanied by a question that problematizes Gallardón’s supposed defense of unborn life. The maternal figure, bent over in her attempt to push a heavy wheelchair, asks: “why so much concern for the unborn if then they abandon and despise the one who is already born?”. Given the cuts implemented by the PP Government to support care work to dependent and disabled people, cuts that left families to shoulder the burden of support, the claim to “protect” unborn life appears rather incongruent and insincere. The party that claimed to champion the protection of the life of the unborn condemned its citizens to a life of misery. The rightwing Government’s hypocritical stance on life, ruthlessly capitalist measures, and cuts to gender equality caused a wave of feminist responses that exposed the duplicity of Gallardón’s conservative legislative proposal.

The duplicity of the PP Government concerning social policies also finds expression in other posters that condemn highly suspicious discourse in a country whose peculiar path to democracy and gender equality is characterized by a lack of State support in childcare policies. While the right decries the so-called “demographic winter”, sociologists and demographers maintain that, much like Italy, this southern Mediterranean country has been “short on children and short on family policies” for a long time (Delgado et al., 2008, p. 1059). Paradoxically, instead of addressing structural obstacles, right-wing policies favored a return to traditional gender roles. Esther Vivas (2012) underlines, “the current solution to this crisis tries to bring women back home, resurrecting outdated family and gender roles. It constitutes a full-blown offensive against economic, sexual, and reproductive rights” (para. 12). Add to this the impact of the austerity measures implemented since 2010 in response to the economic crisis, and the result is a deeply antimaternal climate.

Blind to this social reality and amid an economic recession, Gallardón shamelessly stated that the new abortion bill would actually grant women the right to have children. “I think about women’s fear of losing their employment”, he declared with great paternalism as he claimed that his proposed legislation would safeguard women’s rights, yet he forgot how much his own party had contributed to dismantling all the mechanisms that might prevent a company from firing a woman when she was pregnant (Gutiérrez Calvo & Morán Breña, 2012). This was the party that had shown no mercy towards single mothers and families who could not pay their mortgages and so were evicted, left without any legal or economic protection. In allusion to the ruthless eviction policies that left thousands of women and children homeless while allowing banks to expropriate the property of those who lost their jobs and could not pay their mortgages, well-known graphic artist Susanna Martín composed a visually striking poster. Famous for her social engagement and co-author with Isabel Franc of graphic novels such as Alicia en un Mundo Real (Alicia in a Real World; 2010) and Sansamba (2014), and coordinator of Wombastic, she drew a politically significant message. Against a dark gray background, the torso of a woman dressed in a white t-shirt is ready to participate in a boxing match and displays the slogan: “not even God will expropriate my uterus”. In her exposure to the extraction policies enacted by Marino Rajoy’s Government, Martín, like other illustrators, shows an empowered female subject intent on defending her rights.

Many of Wombastic’s pictures foreground messages that insist on the right to self-determination by asserting women’s ownership of their own bodies. In doing so, they mobilize images of the womb, the belly, and the vagina to show that women are unwilling to abdicate their corporeal sovereignty. Women’s abdomens thus become the surfaces onto which the rejection of the new anti-abortion bill finds expression. Between January and September, when Gallardón resigned as minister of Justice, women’s anatomy was mobilized in various forms, all of which were united in condemning reactionary politics. Thanks to Wombastic, the world of illustration and graphic narratives saw the womb become a powerful site of political activism in defense of women’s rights, an embodied form of revolt, which successfully contributed to “aborting” Gallardón’s attempts to restrict women’s reproductive rights, as indicated in the last image uploaded to the Tumblr on September 13, 2014. As a constellation of powerful images, Wombastic successfully implements feminist humor to spur communal action. In doing so, this digital network stands in opposition to the institutional backlash orchestrated by the Spanish right wing and effectively challenges patriarchal structures.

5. Conclusions

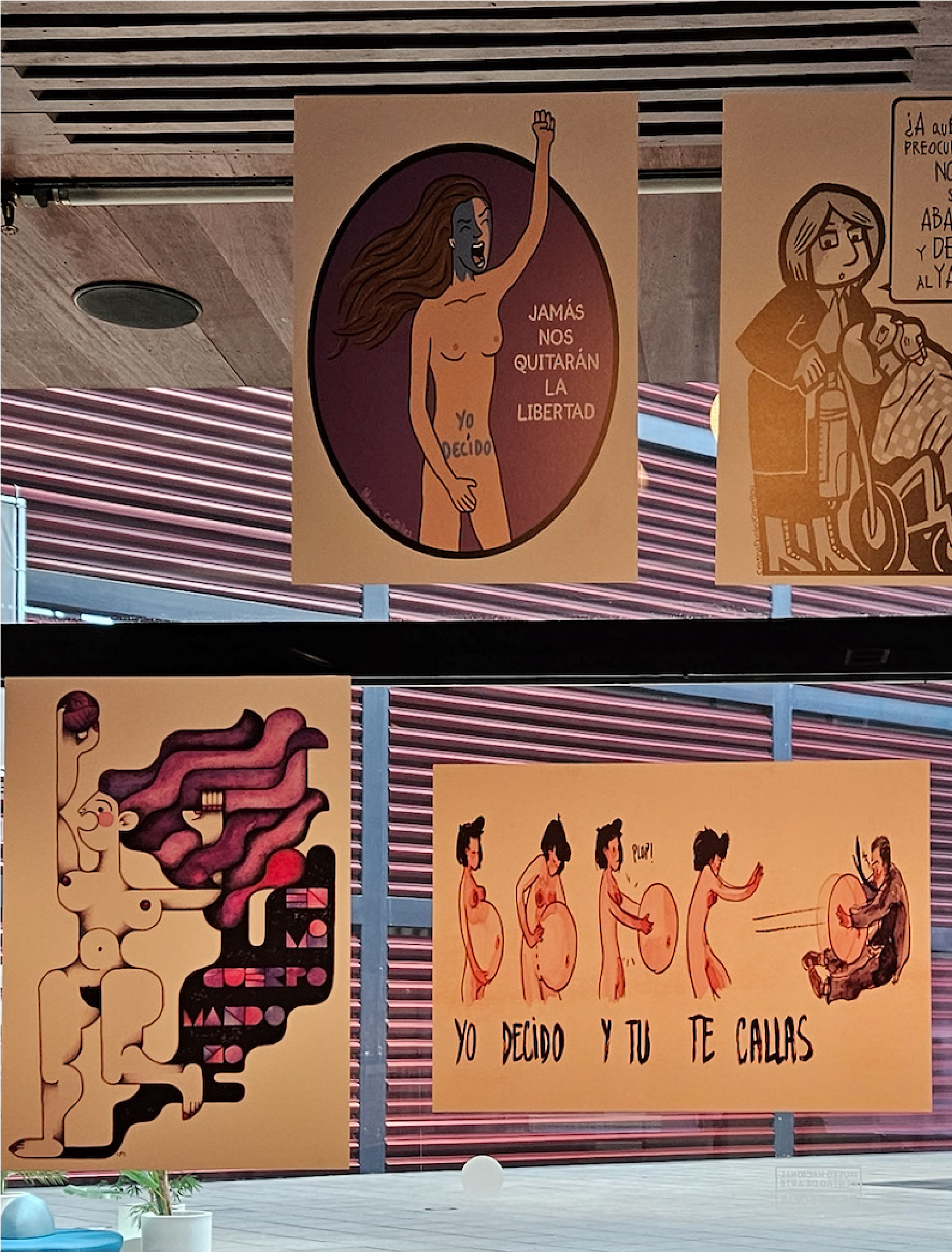

The afterlife of this collaborative enterprise, still available online, continues to attest to its significance. The inclusion of several of the illustrations uploaded to Wombastic in the context of the recent art exhibition “Mujercitas de Todo el Mundo, Uníos! Autoras de Cómic Adulto (1967-1993)” (Figure 7), held at the Biblioteca y Centro de Documentación of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid (February 24-June 9, 2023), further affirms the artistic, political and social value of this initiative. Although the museification of political protests might be perceived as problematic, placing these images side by side with work by key artists and illustrators such as Montse Clavé, Núria Pompeia, and Marika Vila, among others, inserts them into a genealogy of feminist creators, whose significance is being “rediscovered” by key Spanish cultural institutions. As the selection of illustrations exposed in the library indicates, women’s bodies are resignified and mobilized following a feminist visual tradition that reflects women’s struggles of the 1970s as well as the online and collective social movements of the 15M Indignados protests. From the digital domain to the public squares and thence to the walls of a progressive museum, this kind of collective feminist action proves the centrality of feminist creation in effecting social changes. In the end, feminist political cartoons open the doors to a new imaginary aiming “to be able to collectively create and transform our conditions of existence” (Garcés, 2013, p. 22). In creating a collectivity united in its attempt to preserve reproductive rights against State intervention, Wombastic activated the creative potential of political illustration, bridging the gap between academic feminism and popular culture in a virtual medium ripe with possibilities for street interventions.

Credits. Marina Bettaglio

Figure 7 Wombastic images included in “Mujercitas de Todo el Mundo, Uníos! Autoras de Cómic Adulto (1967-1993)”, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, July 9, 2023

The illustrations here studied establish a dialogue with several strands of feminist thinking that span from Simone de Beauvoir’s theorization to a more joyful and playful “vibrant” feminism, to use Ana Requena’s (2020) notion. As a result, many of the visual-verbal compositions suggest a ludic approach to sexual and reproductive health, reclaiming pleasure. Foregrounding a multiplicity of empowered subjects who are unafraid of enjoying their sexuality, these feminist interventions attest to the effervescence of the Spanish comics scene and its potential for political intervention.

texto em

texto em