1. Three Women Authors in the Contemporary Portuguese Comics Scene

The Portuguese comics scene has lived in perpetual crisis mode for 40 years. Since the demise of regular comics magazines for a broad audience widely distributed by commercially sound distribution networks, production has followed mainly hazardous paths while sporadically met with critical success. Nevertheless, one may underline the overall accomplishment of a fluctuating auteurist scene in Portugal, producing outstanding, if under-recognized, work.

In order to pay attention to this production circuit, we must look into publications that are somewhat at the margin of literary institutions and commercial distribution models. This includes independent or small presses, author’s editions, short pieces that have been presented outside published forms or in non-comics publications, as well as the plethora of print objects that we may call “fanzines”. These are the sorts of platforms that I have used for the present chapter. Most of the works I mention are not easily and commercially available books.

One might argue that the weakening of more sound commercial publications opened room for numerous opportunities to attempt a new approach to comics. With the advent of modern democracy in Portugal, post-April 25th, 1974, the comics medium gradually opened to new genres, visual choices, themes, and venues. The didacticism that had presided over most comics production throughout the Estado Novo dictatorship was not completely abandoned. However, new authors tried out other types of artistic languages, from science fiction to surrealism (sometimes both), to realistic portraits of youth, women, ethnic or sexual minorities, and themes of urban decay, financial strife, unemployment, and more (Moura, 2022, pp. 49-65). Third-wave feminism had a significant impact on this comics-making scene because new women authors brought the female identity to the forefront of their artistic endeavors and political concerns. It finally allowed for the emergence of diverse spaces within a heteronormative medium, as most others within the country at the time and, arguably, today. Authors such as Ana Cortesão, Alice Geirinhas, Mimi, Maria João Worm, and Isabel Carvalho put out many comics (more often than not short pieces across multiple collective publications) that either bolstered women’s empowerment or exploited sarcastically the hurdles within a very traditional, misogynistic, patriarchy.

Today, we have many women creating and publishing comics in Portugal, and there is practically no publisher, big or small, that does not have a roster of authors that includes women. I’m referring mainly to publishers that put out Portuguese authors, not solely international translated work. As for non-binary people, less so, but there is some diversity in this regard as well. Moreover, some of these women authors are quite comfortable working on more genre-locked material, ambivalent broader themes, or institutional commissions that do not necessarily have as their main themes political or identity issues that relate directly to womanhood, as it were. Such is the case of Joana Afonso, Rita Alfaiate, Marta Teives, Dileydi Florez, Inês Garcia, and Sofia Neto, among others. This does not mean, at all, that these authors do not pursue a feminist position in their own private lives or that their work cannot be read from a feminist perspective, but solely that their output is not unequivocally exploring such issues. A propos an exhibition of four women comics artists at the “Amadora Comics Festival” of 2022 (in which Mosi, one of our authors, participated) Sara Figueiredo Costa (2022) wrote that stories may “rummage through family memories, daily life episodes, observations of a world that reaches us through the multiple screens and narratives that we listen to or experience” (p. 4). Even if these stories are created by women, have women protagonists, or both, they are, above all, “stories that cross our shared present, whether by the manner after which they question the identities that construct us or by the attention that they deconstruct preconceived ideas and prejudices that still define the way we live” (Costa, 2022, p. 4).

However, or so I believe, what is at stake in the pursuits of the group of women authors I have chosen as the constellation of the present paper is more vehement, intricate, and influential. All of these authors have started their comics production within the last 10 years or less and, through very distinct strategies, moved on to realms of comics-making that explore the construction of the self, experimentation through fragmentation, and the very ontology of comics as a medium. In order to understand how they do this, I will use Peter Wollen’s counter-strategies to describe formal choices and some of Sianne Ngai’s (2012) aesthetic categories and emotions to delve deeper into their meaning-making modes.

I shall begin with a presentation of each of these authors.

Hetamoé is the pen name of Ana Matilde Sousa, born in 1984. She is a visual artist, an art and comics lecturer, and a brilliant scholar and researcher. Her main body of work is quite influenced by specific formal and thematic traits from Japanese comics or manga, especially its more alternative circles. Her work is tinted by notions such as the abject, the grotesque, the excessive, and the extreme, and she creates disturbing amalgamations between the cute/kawaii styles and more violent and pornographic genres. Her very signature is a portmanteau between the so-called “ugly/bad” manga style, known as heta-uma, and moé, a very strong affection towards characters of Japanese popular visual culture (Sousa, 2020; for heta-uma, see her “Glossary”, entry 21; for moé, 23). She has launched several fanzines exploring harsh visuals - between drawing, collage, appropriation, and digital manipulation, among others - and shorter pieces in anthologies or short booklets. She also signs with her own name other types of comics material, such as Einstein, Eddington e o Eclipse - Impressões de Viagem (Einstein, Eddington and the Eclipse. Travel Impressions), which I will not include in the present chapter, even though in a different assessment it could very well warrant a co-joint consideration.

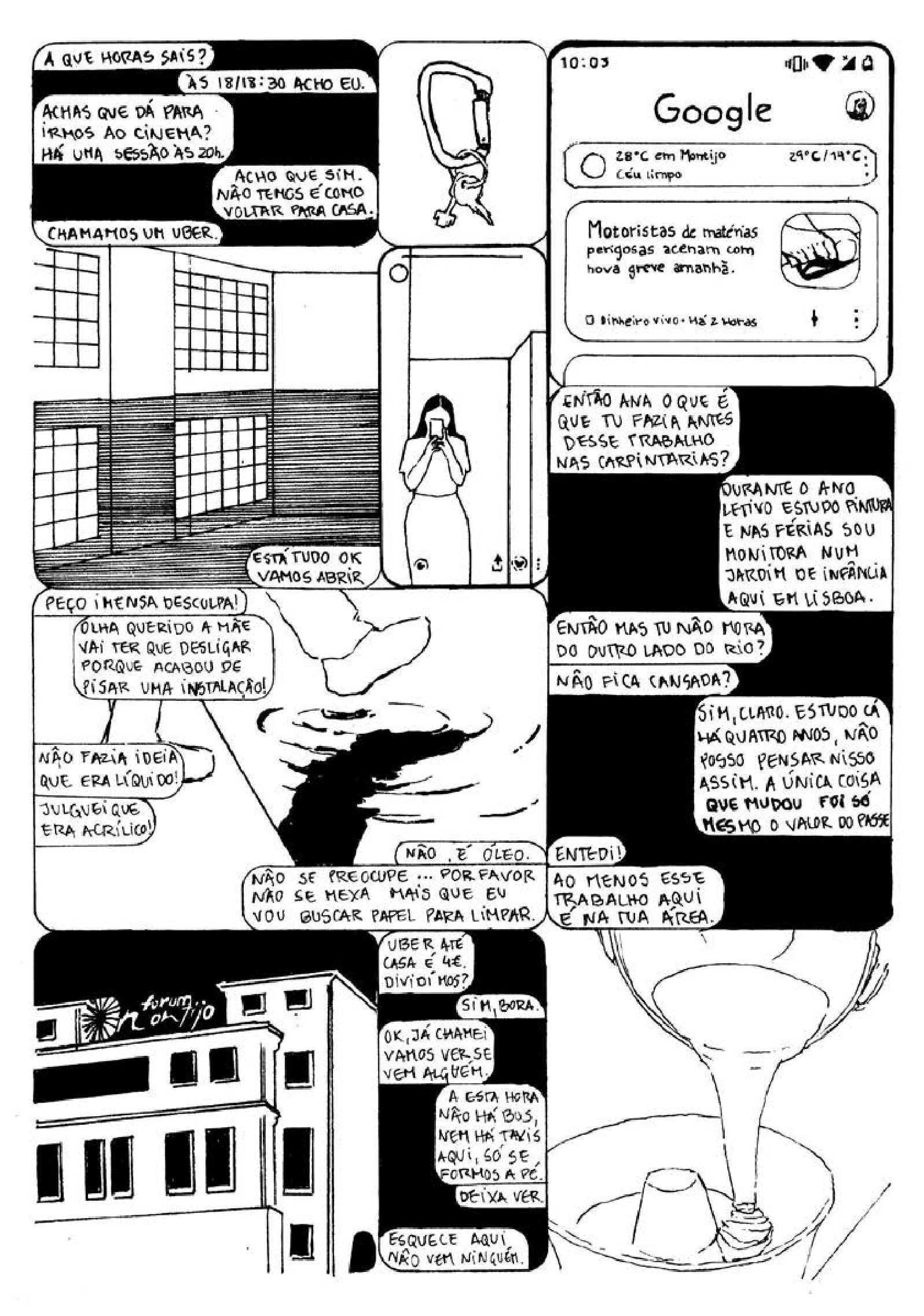

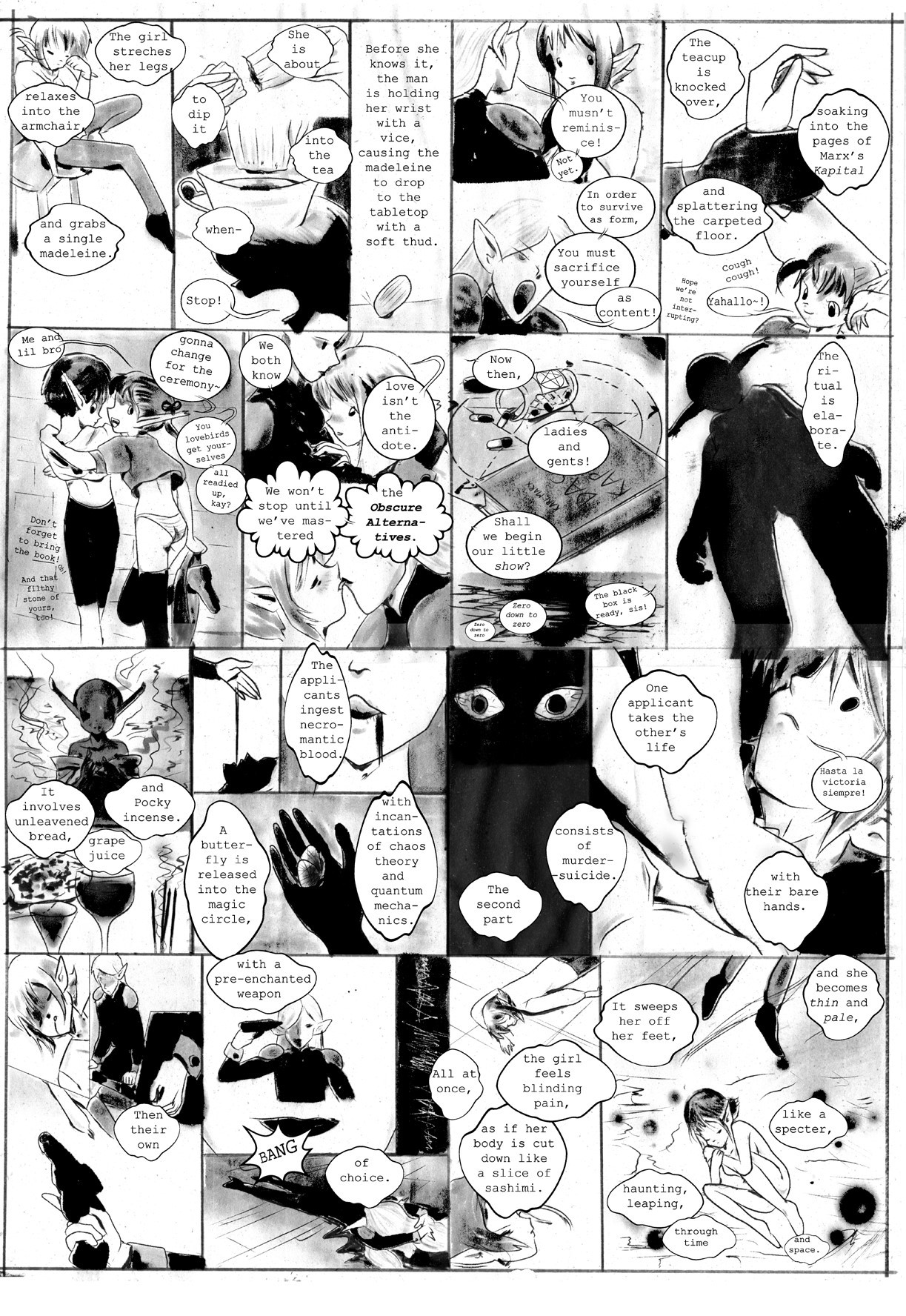

The author, in the They Say That Clovers Blossom From Promises (hereafter “Clovers”; Hetamoé, 2015a) piece, addresses the loneliness that stems from love affairs gone wrong, the disappointment of personal expression, and how desire constitutes the very self. These could be seen as Hetamoé’s permanent theme throughout her oeuvre, as this piece is less structured as a story than a flux of phantasmatical, holistic impressions. One could, in a brief glimpse of “Obscure Alternatives” (Hetamoé, 2015b; Figura 1), think that this would be a high fantasy story, with cute elves having a conversation, even if there are modern objects (cell phones, a gun).

Source. From “Obscure Alternatives”, by Hetamoé, 2015b, in Clube do Inferno (Ed.), QCDI 3000 - FEAR OF A CAPITALIST PLANET, pp. 3-8. Copyright 2015 by Chili Com Carne.

Figure 1 Obscure alternatives

However, the verbal captions seem to stem from a disembodied narrator, and some snippets of dialogue, very emotionally intense, cannot be clearly attributed to the characters we see, creating a very complex mesh of metalepses. It is as if the text - very few speech balloons have attributive tails - created a sort of poetic fog overshadowing the concrete experience of the images’ storyworld. The intertext mesh is quite dense, with references to Marxist theory, Satanic rituals, and numerous obscure allusions to Japanese popular culture (the title is a reference to a song by the new-wave English band Japan). It forces the reader to engage with the hard-won deciphering of such friction between apparently different referential worlds. Elsewhere, I have compared this short piece to a version of the classic bunraku piece The Love Suicides at Amijima as if under the famous dictum from The Communist Manifesto (Marx & Engels, 1848/2012; partly the main influence of QCDI 3000 - FEAR OF A CAPITALIST PLANET): “all that is solid melts into air”. In the following analysis, one must bear in mind this permanent tension of construction and dissolution, dematerialization and rematerialization, in this author’s work.

Joana Simão, more famously known as Mosi, was born in 1995 and has been a tireless creator, facilitator, and teacher of comics. If some of her first output was clearly and unabashedly committed to clear-cut genres, from her young adult autobiographical road trip chronicle with Altemente and her high fantasy graphic novel with Nuno Duarte, The Other Side of Z, she quickly swerved into more experimental territories, both at the material and textual level, turning to small press formats and even web-bound work to do so. She is extremely active on Instagram, for instance. Nonetheless, for this paper, I will only delve into printed work. Her work always questions comics’ usual strategies of figuration, composition, narrative, poetics, coloring, and cultural underpinnings.

Her short comics share several thematic concerns, subject matter, as well as a semi-autobiographical voice that allow us to consider it as an ongoing, unified project, somewhat as I have been arguing in other projects about artists such as Edmond Baudoin, Marco Mendes, and Francisco Sousa Lobo (Ana Margarida Matos also falls into this possibility). However, she does not always clearly engage with an autobiographical pact. The “I” pronoun may well be present, but there are no visual or textual hints that allow us to be certain that the voice (quite often disembodied) is speaking of/from the empirical Joana Mosi. Even the untitled Amadora piece, which discusses “my maternal grandmother” with actual names, precise dates, and detailed biography, does not offer an indisputable link.

The third author is Ana Margarida Matos, born in 1999. After launching a couple of fanzines around 2020, she published a widely celebrated book, Hoje Não (Not Today; Matos, 2021). This 120-plus page book can be described, although superficially and incompletely, as a COVID-19 lockdown journal. In fact, as the result of winning a comics competition (Chili Com Carne’s 2020 “Toma Lá 500 Paus e Faz uma BD!”), she dedicated herself to registering carefully for six months her life, a page per day in 2021, as a creative routine. However, she did not succumb to what most comics and cartoons that belong to this category did, which was basically presenting observational humor around the same handful of immediately tired tropes. Quite the contrary, she turned this occasion on its proverbial head to mold a profound graphic essay on her own interiority, health, identity, as well as the very social organization that we inhabit and discussing possible alternatives of categories such as labor, economy, empathy, and so on. At the same time, with creativity at its core, this book reinvents the very visual and compositional tools of meaning-making in the comics medium using recurrent fragmentary self-portraits, graphic ritornellos, themes and variations of note-taking and journal-writing, and more. This quickly became one of the most thought-provoking projects of Portuguese longform comics in the last few years. Both her previous and subsequent work, despite being slightly overshadowed by the larger reception of Hoje Não, also goes into enmeshed issues of self-presentation, communication and artistic expression, social networking and social masks, precarity, and suburban life.

Perhaps Matos’ (2021) Hoje Não is the most grounded and referential of these three authors. Numerous calls to Portugal’s contemporary, specific, historical situation are presented as par for the course in a diaristic mode. Even if we can create connections between historical actualities within Mosi’s work, it will always be based on educated guesses and assumptions, given that Mosi tends to erase place names, time stamps, and other concrete mapping strategies. Matos floors it.

As you might surmise from the outset, I want to play up two main traits these three women authors share. On the one hand, of course, they share a superficial gender identity, also reflected somewhat in themes and protagonists, as I have briefly mentioned. In that regard, through fictive stories with female protagonists, autobiographical or semiautobiographical work, or other textual strategies, but above all, in which empowerment and self-reflection are key subjects of the storylines, they construct feminist storylines. Even if the story makes the character deal with significant inner turmoil, overwhelming trauma, or societal forces, or contrastively, with quite serene, intimate moments, in the words of Roberta Trites (1997), “the feminist protagonist need not squelch her individuality in order to fit into society. Instead, her agency, her individuality, her choice, and her nonconformity are affirmed and even celebrated” (p. 6).

On the other hand, they also share a kindred formal and material attitude by deploying counter-strategies to comics’ more mainstream stylistic choices. Comics is a medium that quite often, if not always, reveals its constructedness, and sometimes this awareness can be used for emancipatory purposes. To a certain extent, these strategies can be compared to what Peter Wollen (1972) calls the “seven deadly sins” of countercinema, values used to the contrary to normative expectations of orthodox cinema (or “virtues”). Cinema, of course, is a medium with a powerful history and extremely significant critical and theoretical reception. But comics has its own conventions and traditions, its history and social developments, positional and methodological specificities, affordances, and expressive traits. Comparative studies abound, too many to mention. I will be using Wollen’s categories - out of his order, which I believe is not fundamental - to guide us through the formal venues used by my three authors.

As we shall see, Matos’, Hetamoé’s, and Mosi’s texts do not follow orthodox comics signatures, disrupting meaning-making. One such aspect is the way they remediate digital native forms (social media interfaces, icons, emojis, framing devices, multi-channel narrative strands), which leads me to call them “post-digital” in the title, however, which is paramount, without entirely divorcing from the medium known as comics.

2. Meaning-Weaving Through Counter-Strategies

2.1. Estrangement

One of Peter Wollen’s (1972) most alluring “counterparts and contraries” to “the values of old cinema” (p. 2) is that of “estrangement,” precluding a facile, faulty identification. I do not have the time here to go into the problematic notion of identification, something habitually engaged with in such a fashion that it conflates what it means in the field of psychoanalysis and what it means in semiotics. Suffice it to say that the adoption of an advantageous point of view (primary semiotic identification) or the proximity to a given character within the storyworld (secondary semiotic identification) within a visual medium such as comics or cinema has nothing to do with the acknowledgment of the self as an autonomous entity and other psychoanalytical structures (still quite informative, I am drawing from the synthesis by Aumont, 1990). Moreover, I have dealt with this subject elsewhere (Moura, 2022, p. 21), preferring to engage with Kaja Silverman’s notion of “heteropathic identification,” describable as “a form of encounter predicated on an openness to a mode of existence or experience beyond what is known by the self” (Bennett, 2005, p. 9). In other words, while empathy is a most welcome sentiment, it is easy to fall into an erroneous feeling of understanding what is at stake with the individual’s (fictive or otherwise) life story without leaving space for critical distancing.

Such a critical stance is rather reinforced by “estrangement” counter-strategies.

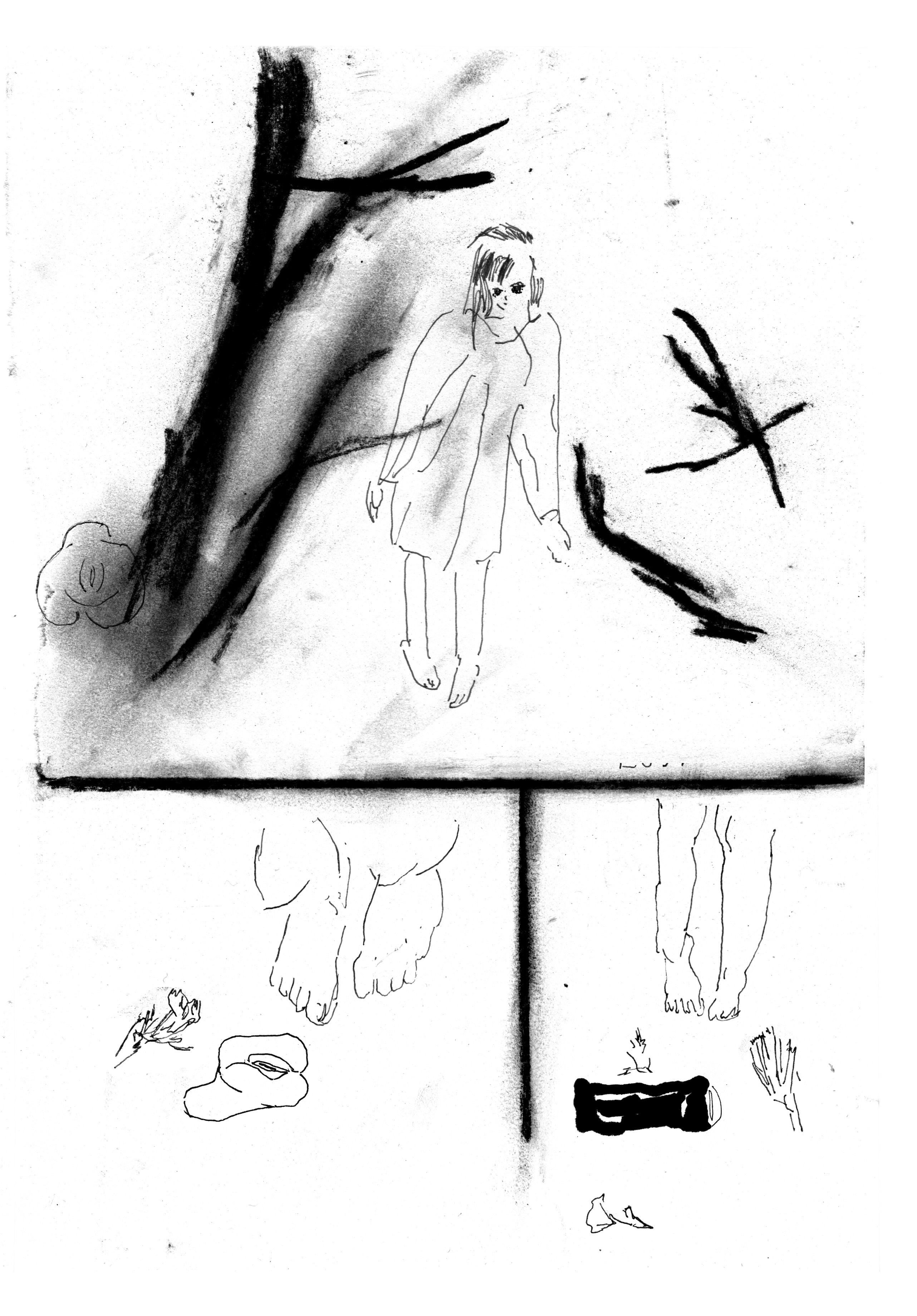

Some of the devices used by the authors start with the very option of not presenting characters as fully-fledged embodied characters. Either the representation strategies present the characters, especially the protagonists, as fragmented bodies, drawings crossed over by lines and smudges, or the authors use very tight shots that either show a snippet of the faces or bodies (e.g., hands) or even opt for framing that erases the character’s participation altogether.

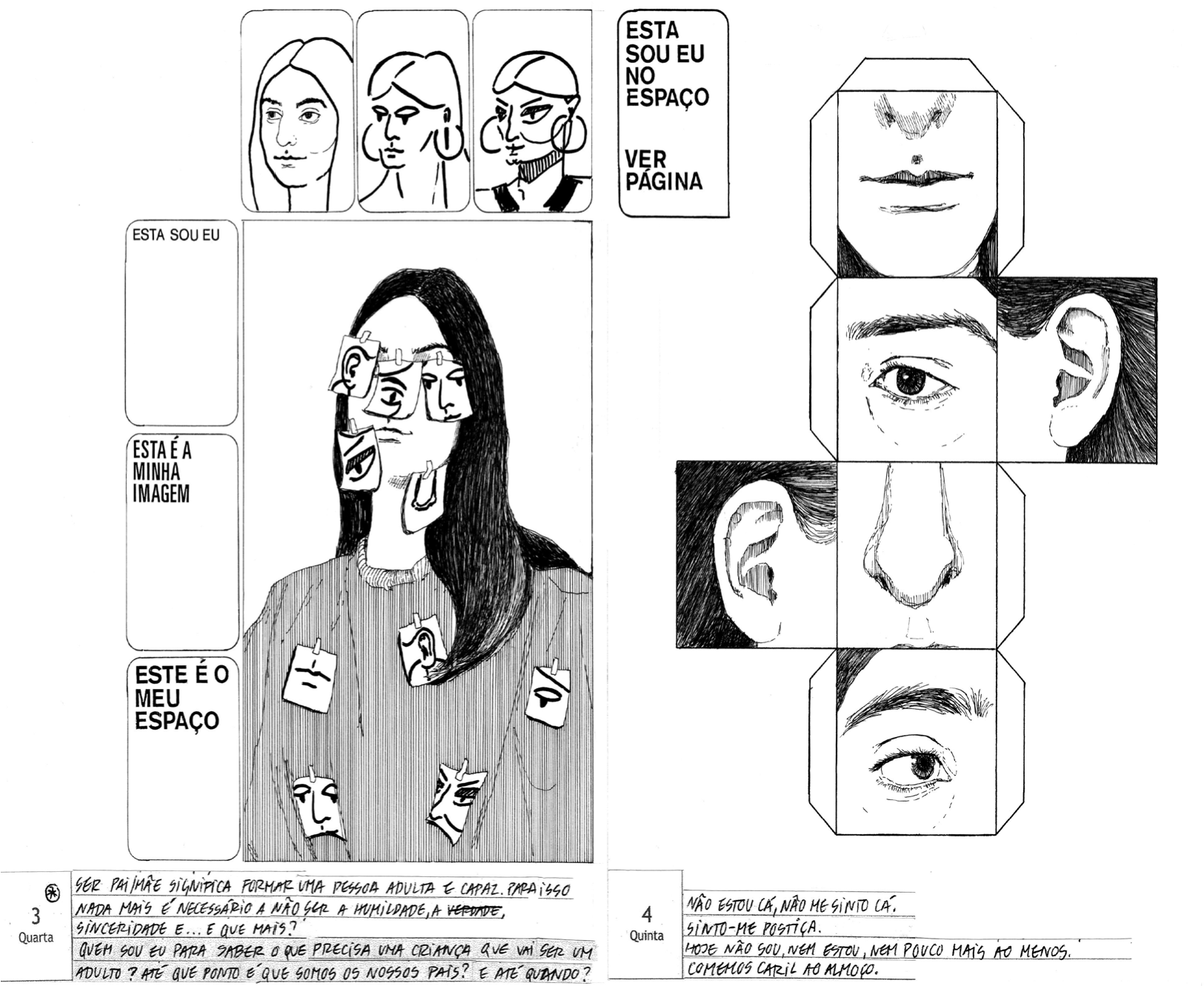

Ana Margarida Matos is, arguably, the author who most engages with a clear autobiographical discourse. There are enough visual and verbal clues that allow us to understand that the protagonist of her stories is the author herself. Many of the self-portraits, instead of following a more classic representation, where authors represent themselves as “third person characters” just like all others, at least at the level of the visual track (Moura, 2008, p. 92, 121-122), are shattered in reflections and juxtapositions. In Hoje Não (Matos, 2021), she draws a self-portrait with post-its that show different face parts in the wrong placements, as the verbal track declares: “This is me. This is my image. This is my space”. A recurring flexagon shape with parts of the face pops up repeatedly, sometimes in other forms, throughout the book (Figura 2).

Source: From Hoje Não, by A. M. Matos, 2021, pp. 20-21. Copyright 2021 by Chili Com Carne. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 2 Hoje não

There is a Rolleiflex camera that she is working on that appears in exploded views or instructional drawings, perhaps as an extension of her own person, reduced to an active recording and reflective device throughout the COVID-19 lockdown. The space is the rooms she inhabits. The rooms, the camera, and the book, everything becomes a camera lucida. Matos deploys daily to note down her own self-construction, a process that necessarily goes through deconstruction. In the case of the Stripburger “Untitled” (Matos, 2023c) short, it seems as if the author depicts herself as an autonomous nose, as if in a post-modern version of Gogol’s famous story, after a page that shows 30 views of her own nose, depicted realistically, as we read “and yet when I look in the mirror, I look for who I am not today”. A decentered subjectivity is at its center, as it were.

The cultural historian Ben Highmore (2010) once wrote that the body might be “the most awkward materiality of all” (p. 119), and Julia Bell (2020) further elaborates when she affirms that “our bodies are contingent, difficult, inexplicable, messy, mortal. Instead of attending to these complexities, how much easier to pretend they don’t exist at all” (p. 24). My three authors may never show bodies in their entirety as an undimmed, pristine, objective reality precisely to counterbalance the body’s commodification. Joana Mosi’s (2021b) My Best Friend Lara, “Postal dos Correios” (Mail Postcard; Mosi, 2023), and the unnamed 2022 Amadora story never show the protagonists completely. The latter shows the hands and feet of what we can surmise are the two main characters (a grandmother and her granddaughter), but their faces are never shown in action. When they do appear, they do so in the shape of an integrated photograph, translated by simplified linework. But even this, we can only surmise from a very oblique context. In “Postal dos Correios”, we don’t even see any human bodies, only spaces in close-cropped shots. As for Lara, its page count and size allow for a more diverse approach and style, but there is clearly a dearth of franker, more naturalized representations of the main character, the narrator. Conflating an intimate diary and an artist’s essay, it is no surprise that Mosi avoids more naturalized fictive pathways. As for the videogame character Lara Croft - the friend of the title - herself, she does appear full-bodied, in actions, within actionable places, but she is presented as a fictional character within the storyworld, so she does not belong to the same ontological level of the narrator (Figura 3).

Source. From My Best Friend Lara, by J. Mosi, 2021b, pp. 44-45. Copyright 2021 by Joana Mosi.

Figure 3 My best friend Lara

In The Apartment (Mosi, 2022a), perhaps the most conventional narrative of the group of texts discussed in this paper, from all three authors, the two main characters, a couple, are drawn in a minimal, cutesy style close to the manga-like chibi signature. The characters often appear with their back to us, but when turned, their faces are blank, with no lines whatsoever (the male character sports a pair of glasses, though). In a typical head-to-body ratio of three heads, their facelessness, allied to their stocky, short bodies, puts them, pardon the pun, head-on into the aesthetic category of the “cute”, declawing whatever threatening power the characters may have. However, it is their almost disposable nature, like the thousands of trademark characters that inhabit a snack packet, that will exert a gravitational pull toward Wollen’s estrangement. Contrary to popular belief and some attempts at theorizing this (McCloud, 1993), “blankness” and “simplification” of characters do not necessarily mean a better identification.

As for Hetamoé’s characters, we face a wider diversity of narrative (or non-narrative) structures and visual signatures across all of her work. However, due to the overall appropriation and remixing of manga-associated styles, one could describe most of these as “cute” characters. But cuteness is not a superficial stylistic choice here, even though it is in contact with the overproduction and hyper-commodification of figurative characters in all things Japan (from manga and anime, that is, narrative-driven products, but also consumer goods of all kinds). In fact, this word is used here as one of our postmodern critical and aesthetical categories, as theorized by Sianne Ngai (2012). For this cultural thinker, when one considers something “cute”, not only is its agency siphoned out completely, but dominance is projected over it. It is a paradoxical engagement of seemingly contradictory emotions, an affective response that harbors a degree of aggression. Hetamoé explores this by splicing such representations with abject themes. Female bodies are subjected to monstrous transformations, animal becomings, vampiric trances, sexual assault, pornographic scenes, and lurid acts, but maintain their well-rounded, cute innocence. Ngai writes: “Realist verisimilitude and formal precision tend to work against or even nullify cuteness, which becomes most pronounced in objects with simple round contours and little or no ornamentation or details. ( ... ) the less formally articulated the commodity, the cuter” (Ngai, 2012, p. 64).

3. Foregrounding

Mosi’s and Hetamoé’s “cutenesses” are quite different, but as we will see, both strive for “less formally articulated” (Ngai, 2012, p. 64) characters and storylines as better to create critical distancing. Part of the visual or material counter-strategies for such formal dimension is analyzable via Wollen’s (1972) value of foregrounding, which acts contrary to transparency. By that notion, Wollen wants to underline formal strategies that impede a post-Renaissance, traditional understanding of the place of composition as a transparent “window” into the storyworld. We have to understand the very fact that even mainstream comics’ pages present already complex compositions of multiple panels (famously theorized as multi-cadre by Thierry Groensteen, 1999). The images, often more than one on one single page, are put into a graphically oriented structure: each panel exists in a diagrammatic relationship with another and thus triggers logicalsemantic meanings. Nevertheless, through several means, these three authors further explore comics’ own opaqueness and materiality via their open-ended structures. The same quality of constructedness of comics comes to the fore through these choices. We can see this exploration of materiality at two very different levels.

The first is related to legibility. As we know, for a long time, comics styles were associated with a streamlined design that aimed for maximum efficiency: simple lines for clear emotions and meanings. Whether through the bigfoot style of classic American animal comics of the 1920s, 1930s, and after, or the post-Hergé clear line, whatever mark appeared within the place of composition had a clear representative or symbolic usage. But modern comics brought about a plethora of expressive possibilities, including those afforded from, or by tapping into, other visual media. We have artists, including Hetamoé, integrating non-representative levels of mark-making in their comics. As an example, let us consider “Obscure Alternatives”, a four-page, two-spread short that was part of the QCDI 3000 anthology (Hetamoé, 2015b), that published material by the art comics collective Clube do Inferno, of which Sousa was a part. This piece integrates a higher degree of what we could call “graphic noise”, blots, over-inked impressions, uneven shading, overlapping of speech balloons and their placement over characters or panel frame lines, and so on.

In a previous piece, “Clovers”, with which she participated in the QCDA 2000 anthology (with only women artists), Hetamoé not only took full advantage of the large format (when opened, the publication is close to a standard horizontal A2 format) but also used it to “scatter” her panels - by that I mean the creation of the illusion of structureless composition -, mixing captions and the typical “decorative” (I am aware of the pejorative sense of this word) elements that populate shojo manga pages: floating hearts, starts, sparkles, threads of glowing orbs, emojis, and other forms, that may or may not be read as mirroring an emotional meaning in relationship to the events of the story. The lack of an orthogonal grid for organizing the multiple panels of wildly differing sizes and captions, juxtaposed in a seemingly haphazard manner, can also remind one of a computer screen with too many open windows and tabs. Remember that comics are always already a medium that allows for, at one time, an overview and a detailed view of the elements within a plane of composition - from single, outlined panels to double spread and beyond. So, all of these elements may be interpreted at different levels of integration, from the apparently demeaning “decoration” to a poignant translation of the character’s inner turmoil. In any case, their very presence, as typical of shojo manga, emphasizing feelings, seems to create suspended moments outside the normative temporal narrative flow.

A second level can perhaps be seen as simply a specific variation of the former. I want to underline how the visual composition of these authors draws heavily from the multitasking aspect of video games, internet use, and smartphone screens. In the case of Joana Mosi’s (2021b) Lara, we find several strategies, both thematically and compositionally, reminding one of certain displays of this nature. A page may show a floating panel, but this panel is drawn after an Instagram post, with a handle profile, caption, hashtags, like buttons, number of visualizations, and so on. The page will also include a timer, a chat message, status icons, and other elements. The Amadora piece, for instance, dispenses with full-bodied characters altogether and presents a tight mesh of panels that focus mostly on the hands of the participating characters. When wider shots appear (also within larger panels), we see a remediated photograph, from which sometimes the faces are erased. Small blue square panels also appear, with white line drawings with very simple captions reminiscent of either traffic information signs or highly-stylized Instagram posts (all of them carry category labels for food, fashion, or music genres as part of the narrative about which more below). Throughout the story, there are some small icons, emojis, and checks, as if integrating WhatsApp messages in the field of composition. “Postal dos Correios” is a very short sequence - more than counting pages, we should mention that Mosi uses a composition technique akin to what Chester Brown accomplished in the late 1990s, with fluctuating solitary panels on a page, or a couple of them. This story contains 11 panels across eight pages. But it starts with a metaphor, comparing “traveling to a new place” to “unlocking a new level in a videogame” (Mosi, 2023), showing how the familiarity of walking these spaces dispenses aids, as it becomes part of a bodily routine.

Matos also includes in her pages many forms stemming from digital tools, explanatory manuals, and other non-narrative visual sources. However, in her case, the diversity and richness of all the pages are so great that it is difficult to see these integrations as different from the “normal degree” of her compositional choices. In Passe Social (Social Pass; Matos, 2019), for instance (Figure 4), several panels seem to imitate full-bodied mirror selfies, showing the main character (extratextual information, such as the author’s pictures and selfies on social media, helps in identifying this character with the empirical author) taking pictures of herself. However, not only is she too far to fully recognize her, but there are no facial marks, just a blank surface, and the phone hides her face. It is a complicated hide-and-seek game of self-representation. There are also screengrabs from Google searches, Instagram posts, an mp3 player, the phone’s pull-down bar, and printbased communication devices such as a daily planner (which would become the very groundwork of Hoje Não’s structure). Moreover, there are also seemingly non-narrative panels with iconic objects that act as “zooming in” daily activities - a spoon, a can of tuna fish, a single fusìllo - and short explanatory sequences of an action - baking a cake, preparing tea.

4. Narrative Intransitivity

Hetaomé, Mosi, and Matos can be seen thus as authors who employ, deploy, and remediate several visual storytelling techniques that are not only native or specific to the comics medium but also from other media forms such as videogames and social media, which lead to these remarkable page composition choices. Moreover, these choices also impact the very “discursive track” of the stories, or their plot, as it were. The very first counter-strategy value discussed by Wollen (1972) is narrative intransitivity. It means that a more habitual cause-and-consequence flow is interrupted, forcing the reader to permanently re-focus her attention instead of falling into the illusion of following a natural sequence of events. Wollen is implying here the stimulus for an enhanced, attentive state. However, and somewhat paradoxically, when using the devices I just described, the dynamic fragmentation of the comics’ authors seems to set in motion at one time the mirroring of the contemporary atomization of attention brought by web user multitasking abilities but also its new affordances. Allow me to quote Julia Bell (2020) at length from her short but riveting essay Radical Attention:

in this environment of constant, low-level distraction our attention is often divided across many different tasks. We might scroll through Instagram while watching TV, or zone out on Facebook when we’re at a bar with friends. But what is happening is that we are not actually paying attention to anything. The social media scroll or the conversation or the programme all mush into one data stream that literally passes through us, rather than being stored for future use or recall. Our capacity to make memories is most affected by this kind of divided attention. ( … ) In the midst of all overstimulation we are unable to lay down new memories, which means we don’t remember much of what we are doing either. (pp. 73-74)

Julia Bell’s (2020) vaticination may sound disparaging, but, firstly, it will resonate with different parts of my three author’s texts, and secondly, what the author wants us to focus on is a mode of “being present”, as she writes, drawing from Simone Weil. A “different way to relate to each other ( … ) not in competition, but in connection. Not as atomised consumer units, but in solidarity” (Bell, 2020, p. 33). One must be wary of oversimplifications, but comics is a medium with an ingrained “embodied, multisensory reading process” that calls for hyperreading and hyperattention (Orbán, 2014, p. 169). So even if these authors pantomime the volatile and adaptable digital multiplicity of meaning-making items (images, texts, icons, graphs, framings), they are weaving its many strands as meaningful. Instead of creating a barrage of unrelated atoms, they present elements that the reading act will weave together into a meaningful web.

5. Multiple Diegesis

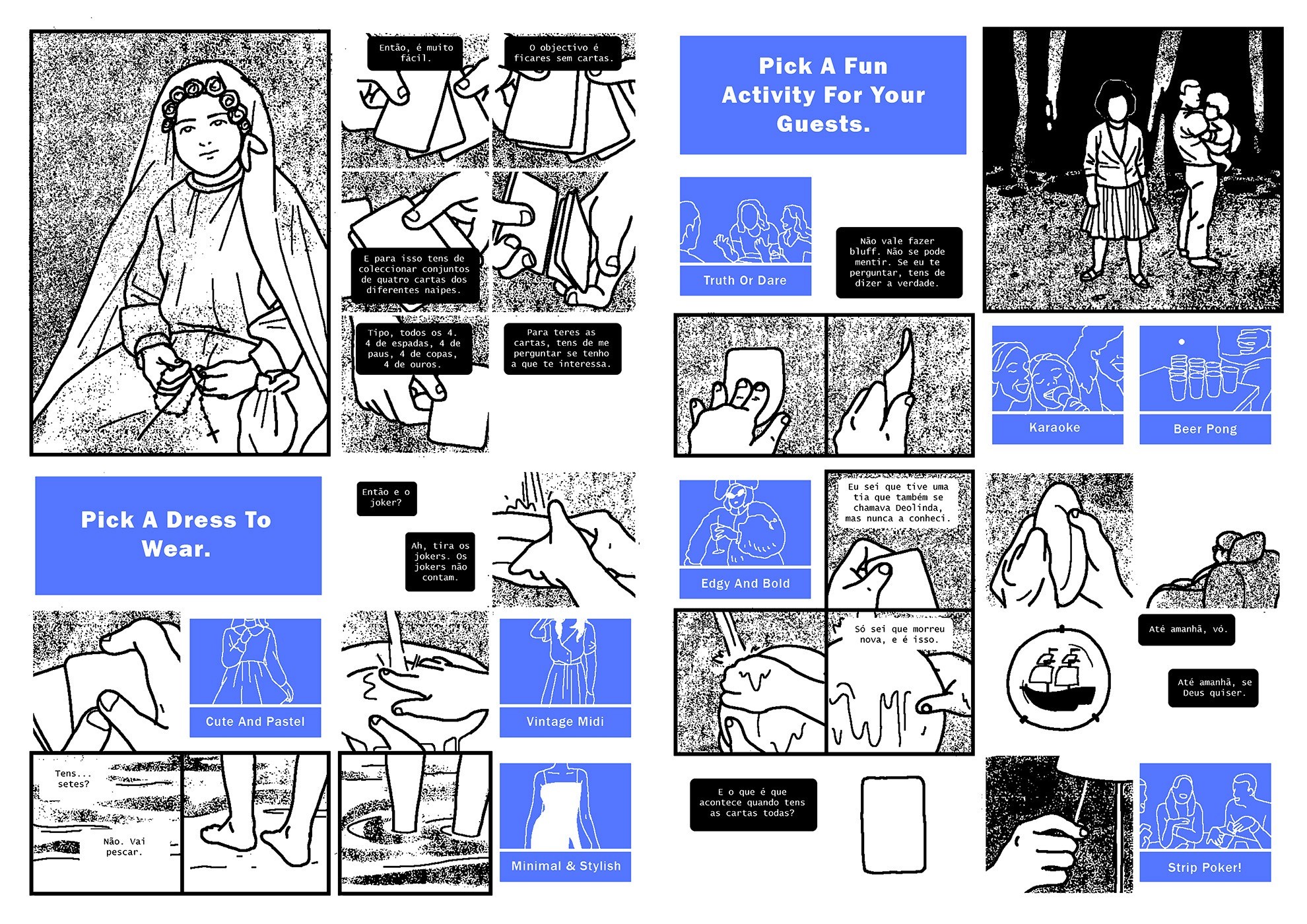

Of course, as in any artistic endeavor, comics-creation exists in a sort of spectrum, such as the one between normative choices and more experimental approaches. There is never an absolute on/off, either/or position. Wollen (1972) opposes single diegesis to multiple diegeses, presenting, on the one hand, dominant Hollywood plot-centered homogeneous storyworlds and, on the other hand, Godard’s “film-within-a-film devices”, where narratives may interpolate one another or even fail in communicating directly with one another. Except for Matos’ (2021) Hoje Não, most of the other elected works are short stories, and all are materially presented as cohesive texts (short story, fanzine, booklet, artist’s book, graphic novel), held together not only by its constitutive materials but also paratextual strategies. As I have been highlighting, one might as well interpret some of the textual, temporal, visual, spatial, and compositional structural choices as rupturing a single narrative track.

In The Apartment (Mosi, 2022a), for instance, the purportedly central storyline - the relationship of a couple - is interrupted time and again by “pictures” (pictures within pictures, drawings within a drawn narrative) supposedly of the apartment below the protagonists’, which is up for sale. But Mosi’s most radical contribution to the multiplication of meaning threads that weave back and forth in the readable plane is undoubtedly the unnamed Amadora piece (Figure 5). We could identify those threads by descriptions that would seem to present a coherent track, such as “dialogue with grandmother”, “playing cards”, and “fill a quiz”. The verbal track may not always coincide with the visual track, and all these threads are shuffled and mixed. For instance, in the questions from a typical internet quiz - “Plan a Party and we’ll Tell you What Cake you Are” - the multiple answers are displayed as bright blue squares, but they do not necessarily appear after the questions or even in order. That invites readers to read backward or in complicated tressage associative movements (cf. Groensteen, 1999).

Source. From Plan a Party and We’ll Tell you What Cake you Are! Unpublished 10-page comic, by Joana Mosi, 2022, p. 5- 6. Copyright 2022 by Joana Mosi

Figure 5 Plan a party and we’ll tell you what cake you are!

From the standpoint of narrative organization - the presence of a protagonist, an exact location and time frame of the depicted actions, the centrality of a plot, and so on - it is perhaps Hetamoé the most radical of these three artists, as she explores multiple fashions to weave together the elements of her comics pieces.

Idle Odalisque (Hetamoé, 2012), the oldest publication I will consider here, presents a rather unorderly composition of thick markers-drawn figures as if imitating a young, inexperienced artist or mimicking the heta-uma school. The storyline presents a nubile young woman who can augment her breasts by using some magical eye drops, prostitutes herself to a bear, and ends up by rather playing Scrabble and sleeping tight. While it may remind us of one the numerous and by now familiar pornographic (hentai, in Japanese parlance) versions of folkloric European tales, versions whose emotional impact is emptied by its visual pyrotechnics, these “awkward” approaches become far more disconcerting, by mixing the banal, the excessive, the abject and the absurd.

Yonkoma Collection (Hetamoé, 2014) already reflected a sort of “mature phase” of the author’s discursive processes at the time. Hetamoé was never interested in pursuing a euromanga style or being seen as a Portuguese mangaka, as many other authors who simply adopt stylistic and narrative conventions in a transplanted emulation. We could perhaps identify some almost direct sources for her subject matter and drawing techniques, such as second-generation gekiga luminaries Oji Suzuki and Seiichi Hayashi. Like these Garo alumni, Hetamoé structures her narratives around dream-like fluidity, melancholy, and the poetry of silence and ambivalence. The elements are also clearly present in other Western contemporary experimental authors, such as Aidan Koch, Lala Albert, and Blaise Larmee. But compositionally, Hetamoé uses a very typified form in this project: that of the titular yonkoma, a usually humorous strip consisting of four equally sized panels arranged vertically on top of one another (Figure 6). The publication is a “collection” of 17 of such strips, going through all imaginable combinations, from almost “silent” strips to some with dialogues, from either dense and concentrated depicted actions to more expanded structures or even visual lists of similar objects. There is an overarching theme, to be certain - “love hurts”, we might sum up - but the author unlocks unexpected and productive meanings from these juxtapositions that elicit the reader’s participation in performing associations.

Source. From Yonkoma Collection, by Hetamoé, 2014, pp. 4- 5. Copyright 2014 by Clube do Inferno.

Figure 6 Yonkoma collection

Muji Life (Hetamoé, 2016) is a full-fledged solo publication that has two parts and is an object that rethinks the way comics can communicate and present themselves formally and materially. On the one hand, we have a square book that resembles the catalogs of the famous Japanese brand of household goods and a sort of companion essay presented in a separate yet integrated brochure titled Yangire/Yandere. In this project, Hetamoé wholly consumes the unison between the grotesque, the erotic, and the cruel. The essay deploys tools from cultural studies, feminist studies, and other academic fields to discuss the notions of its double title, which refers to specific typified female figures from some Japanese comics genres. In sum, we may describe these yangire and yandere figures as very young women characters, with candor and a mollified demeanor, but serving as a mask of a hidden facet of extreme violence. There are significant differences between these terms, that Hetamoé brilliantly elucidates, but for our purposes, suffice it to say that both nevertheless underline and support a heteronormative image of women as, and I quote Ngai (2005, p. 95) again, “animated”, that is to say, “too emotional,” and, therefore, more disruptive - in such a view - when engaging in violent acts such as dismemberment or murder. Thus, the Muji Life narrative, presented as a series of more or less coordinated grids of four square panels, as if presenting products, can be seen as the illustration, as it were, of the essay’s lessons. The notions, objects, and discussions from the essay feed a fragmentary story about a passionate obsession ending in the most abject violent acts.

In 2020, she published Violent Delights (Hetamoé, 2020), almost a paroxysmal corollary of these thematic strands. It quotes from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet play and sonnets, deconstructs manga and anime visual tropes, and discusses issues such as the Anthropocene. At the formal level, it quickly shifts composition choices and drawing strategies in a sort of page-per-page zapping of styles. One could well be tempted to fail to understand its coherence, but the paroxysm may be the very violent act at the core of the most famous Shakespeare (teen) tragedy, which is not a contradiction but rather the confirmation of its powerful passion, reflected in the quote/title.

6. Aperture

An immediate consequence of the multiplicity of narratives feeds into the next of Wollen’s (1972) categories, namely closure vs. aperture. Wollen discusses intertextuality, eclecticism, quotation, pastiche, and irony, but we can also consider a more straightforward relationship between the texts’ parts or perhaps even “episodes”. Indeed, most comics seem to comfortably inhabit the end of the spectrum of satisfactorily concluded univocal storylines. Moreover, from a comics-specific structure point of view, Scott McCloud (1993) quite famously attempted to lift the notion of “closure” as the core of the “invisible art of comics”. According to that early theorist, closure implies an engagement of the readers/viewers in connecting any two separate images and “closing” that gap with acts of imagination, completing actions, surmising events and connections, and eliciting an ethical response, as the readers become an accomplice to any depicted action.

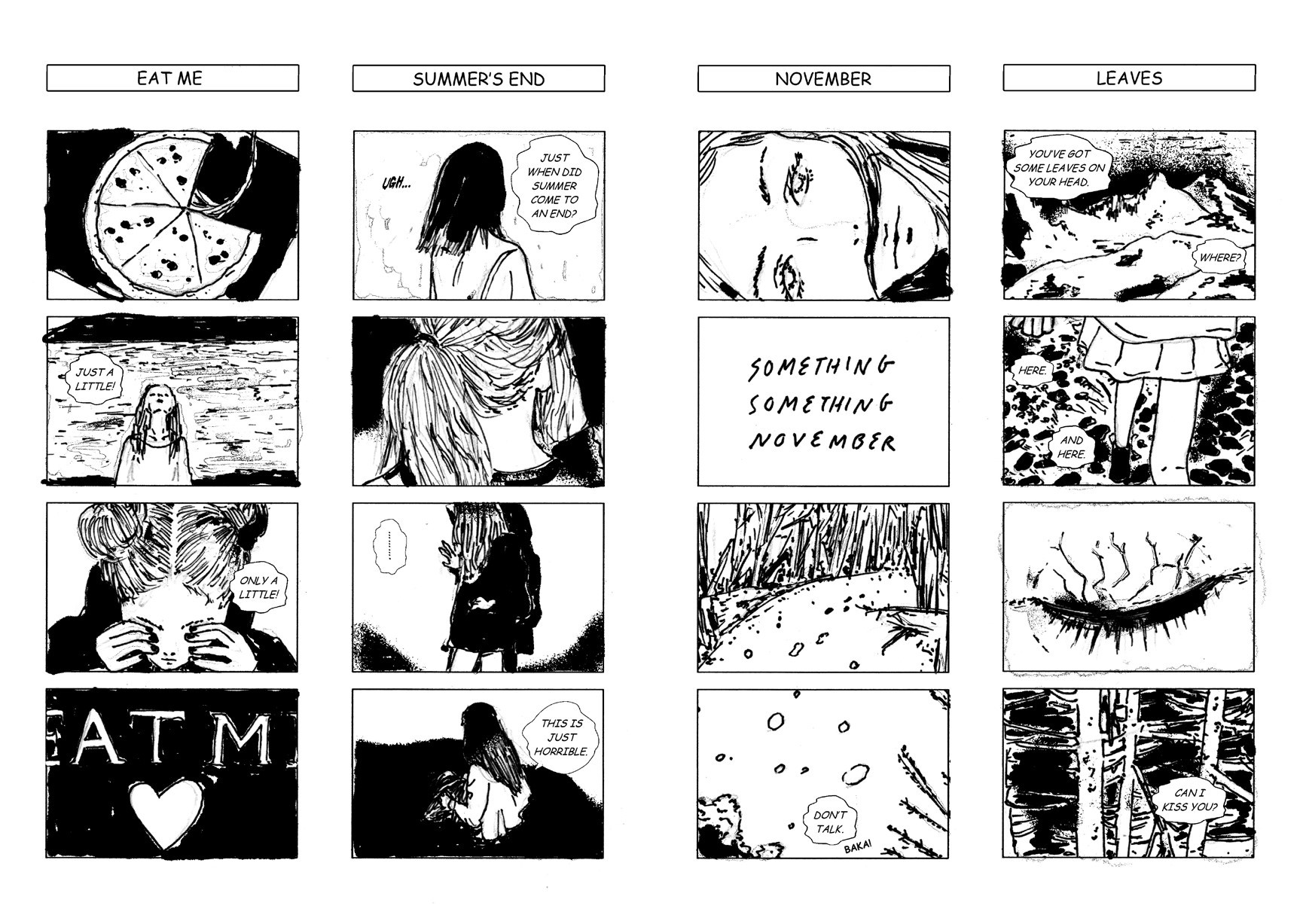

However, the many jarring juxtapositions already mentioned in some of the comics texts by Hetamoé, Matos, and Mosi create an impossibility in suturing all interventions into a single semantic field. Nonetheless, some of the projects discussed here could be described as “closed” from a certain perspective. After all, Matos’ (2021) Hoje Não is a diary that clearly has a beginning and an end, a diary that starts with monumental splash pages and spreads as if declaring its energetic beginnings and ends with a tight, solely textual barrage of daily scribbled notes until even that manuscript ends and we are left with empty daily entries. It is as if the energy ran out, or a sort of dénouement was underway. Mosi’s (2021a) Both Sides Now clashes reinterpretations of two movies, perhaps at odds in terms of critical reception and genre, Yorgos Lanthimos’ 2015 The Losbter and Richard Curtis’ 2003 Love Actually, but which could be subsumed under the protagonist’s (once again, out of sight) appreciative perspective of both. The unnamed Amadora piece could also be seen as an homage to the grandmother figure, whose memories are central to the dialogue and female bonding. A reflection upon a life almost spent and impending death and dissolution, this story ends with a sequence of increasingly blacked-out panels, depicting perhaps the sea covering the sands (this piece echoes, even if indirectly, Federico del Barrio and Elisa Gálvez two-page story “La Orilla”, from Madriz, Number 13, February 1985, and a comparative reading would surely unfold multiple readings).

Nevertheless, those feelings of finality and univocity are but an illusion. Dissolution and confusion are always present and allow for an open-ended structure of most, if not all, of these texts. Matos’ (2021) book opens up with the following declaration: “today is Monday. Today was Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. All except Saturday. All except the weekend”. And it closes with, “today was not Saturday nor was it any day. Today is Monday. Today I was not me. I was not none. Today went by in a blink of an eye”.

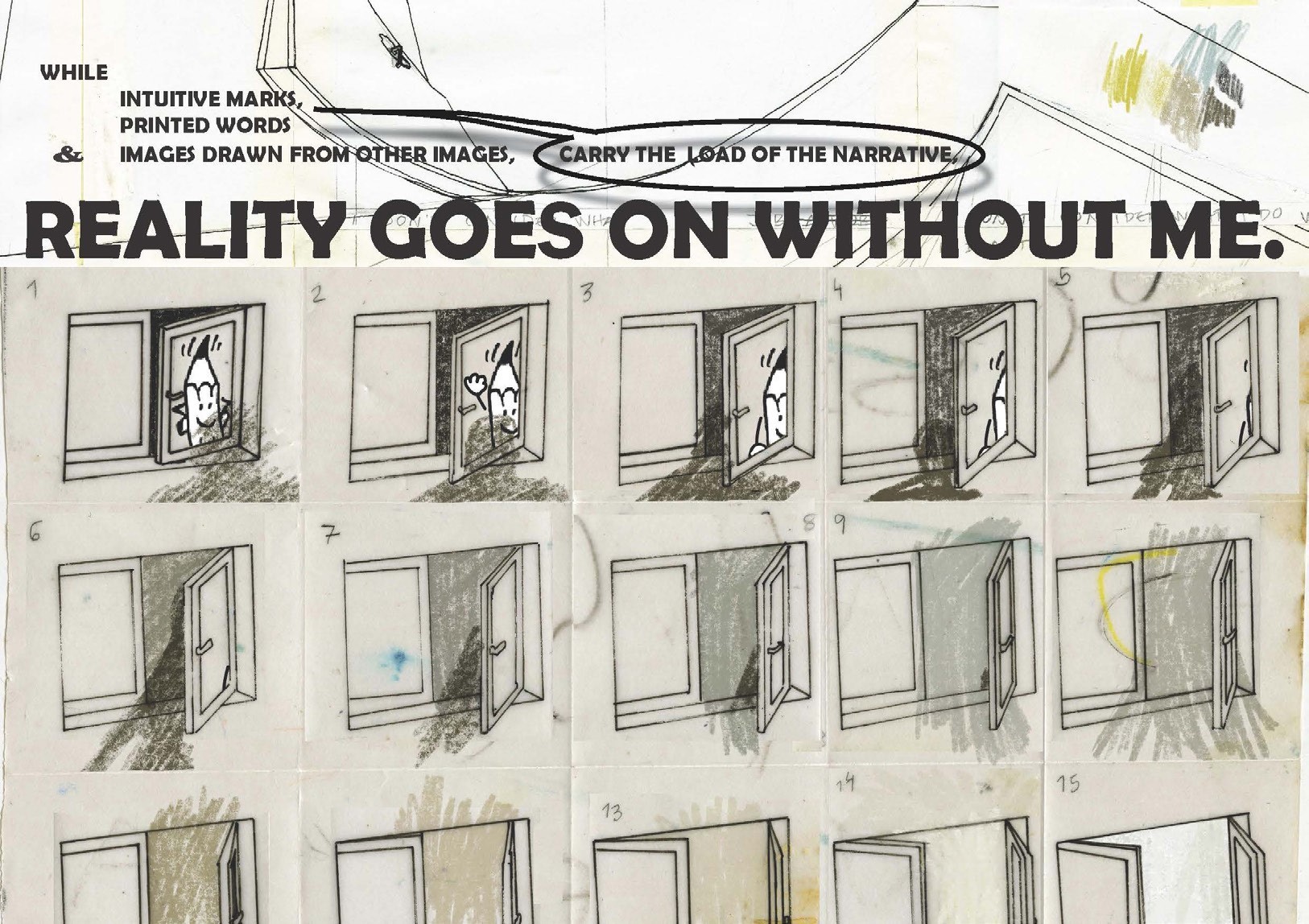

Grapefruit, Matos’ contribution to the Latvian publisher Kuš (unpublished at the time of this writing), is a tour de force about the creative act associated with the comics medium and beyond. Throughout these pages, Matos (2023b) tries to describe what she aims to do when putting words and pictures onto paper in a certain order for meaning to appear while reflecting upon her own identity and self. Creating is self-creating, but doubts and dissolution are always present. She writes, “through this [the] process of selfdeconstruction, I thought myself to the point of becoming my own thoughts”.

The very last page of this small book (Figure 7) has a cartoonish pencil character waving goodbye. But it is a complicated composition: a graphite-made shadowy ghost of a character seems to jump out the window, revealing the pencil to be part of the glass only. Then the windows open again, and the shadow expands and turns into an even denser shape until it disappears completely, and then the pencil appears again with its back to us and waves again before the perspective rises and disappears. Meanwhile, the verbal track (with different types, sizes, and visual presentation, but in a logical semantic sentence) declares: “while intuitive marks, printed words, and images drawn from other images carry the load of the narrative, reality goes on without me. To narrate is to create, to live is to be lived” (Matos, forthcoming). This acknowledgment of a lived reality existing apart from creative work extends the meaning beyond and outside the text. In a blurb to Hoje Não, the artist António Jorge Gonçalves (cited in Matos, 2021) praises Matos’ “virtuously obsessive graphic rigor” in creating what he calls “labyrinth pages”. Labyrinths as traps where one retraces paths endlessly or crisscrosses ways, always returning to new modes of weaving the meanings.

Also, of course, Hetamoé’s radical shifts of style and voice and exploded attention herald an almost unsolvable closure, always relaunching her readers into a frenzy of associative attempts. This frenzy, a sort of emotional and semantic ride we are constantly negotiating as we try to put the pieces together of these books, is its very meaningful core. We are not solely reading these stories in order to reconstruct a plot reducible to a brief outline, and where all the parts contribute to a single, objectifiable, isolable “theme”. Quite the contrary, it is the permanent shifting that is the purpose.

7. Un/Pleasure

As we reach Peter Wollen’s (1972) sixth virtue/sin pair, the one between pleasure and unpleasure, it becomes slightly more difficult to follow within his lines. The very notion is slightly more controversial for our own times, or at least in my own interpretation. First, entertainment is seen by Wollen as part of a consumer society that was, of course, rightfully so, denigrated by a Marxist criticism standpoint. I do not want to go into that much detail about the contemporary alternative economics of indie comics, even though we may be buying here into some sort of co-opting of normalized marketability, but I will note that despite their limited runs (below 500 copies, overall, of each of the mentioned titles), they have, as one says, “sold well”. Hoje Não, for instance, even sold out its Portuguese edition and is about to be published in English by a non-negligible new United States independent publisher. Mosi’s My Best Friend Lara is a hand-made, hardbound, two-color risograph printed book. With its delicate, textured pastel colors - a two-tone forest green and a stark salmon tone - mixed with expressive brushstrokes (even if done digitally), sometimes even close to abstract-like blots and streaks over the figures, it brings about a striking materiality that serves as a counterpoint to its subject matter - the smooth, so-called immaterial nature of videogames and computer - or phone-based media. In fact, by overexposing digital-native forms across her work, Mosi emphasizes their haptic and emotional qualities, and this book object is its most complete accomplishment. In all respects, it is quite close to an artist’s book for its materiality, from artisanal bookbinding and manual interventions, and its very limited print run (a few copies of which were sold with an additional printed drawing). One cannot deny some degree of fetichism at stake here, enhancing its pleasurable features.

However, there is a second level in Wollen’s (1972) writing when he touches on fantasy and its complicated cluster of meanings. In order to simplify, I want to appeal to Slavoj Žižek’s (2008) dictum that fantasy is constitutive of the subject’s reality itself. Allow me a longer quote from the Slovenian philosopher from The Plague of Fantasies:

there is no connection whatsoever between the (phantasmatic) real of the subject and his symbolic identity: the two are thoroughly incommensurable. Fantasy thus creates a multitude of ‘subject positions’ among which the (observing, fantasizing) subject is free to float, to shift his identification from one to another. (p. 7, nota de rodapé 5)

We have spoken elsewhere (Moura, 2022, p. 220) of the “permanently shifting bodies” and the “avatars” of creators dealing with trauma-related autobiographies. We have also mentioned above how these authors present oblique forms of representation of their characters, mirroring this multitude of subject positions. Such exploitation of fantasy, of dream work, elicits some sort of pleasure. But the revolutionary unpleasure championed by Wollen (1972) is still extant: it lies within the provocation of these very shifting representation strategies and multiple foci.

There is probably no other clearer realization of such a paradox than Hetamoé’s pornographically-informed Onahole (Hetamoé, 2013). Materially speaking, this is a very gestural, raw, low-fi affair. This is a classical xeroxed, folded, and stapled booklet made of A4 sheets, with very spontaneous linework apparently drawn in pen, and filled with basic, “dirty” textures that may employ whiteout, graphite, toner dust, or other inks. The figures are bodily but are framed in such a way that they solely reveal the body parts necessary to the minimalist plot, and with straightforward yet evocative, somewhat frantic composition. “Onahole” is the name given to a sex toy, a silicon device that simulates a vagina or anus and is used for penis masturbation. The story presents itself as a text, sometimes written by hand, other times typed, which may point to either a shift within the same unified voice that speaks to the protagonist or alternate voices. As for the images, these depict what looks like flowers, a half-whited-out horse in a landscape, an aroused penis, a young teenage-looking woman, who seems lost, and in at least one scene, shows a disturbing expression of pain on her face, presumably due to a forceful, painful penetration (Figure 8). The situation is indeterminate, but there are sufficient elements to believe that sexual violence seems to be indeed the key event of this short story, even though there are no absolute assurances. For instance, there is no absolute certainty of who the perpetrator is and who the victim is, even though it is not hard to guess from a societal standpoint. In fact, this visual narrative reminds me of Michèle Cournoyer’s (1999) short animation Le Chapeau, in which the visual transformations between the incredibly diverse objects are only decipherable through the enigma created by the very sequencialization of the images. If we consider that these objects of self-gratification, the onaholes, are yet another absolute and quite spectacularly reductive reification of a woman’s or female body, violence is present from the moment of its very conception and manufacturing. However, by intercalating scenes with flowers as well as the recurring word “growing”, perhaps Hetamoé wants to point out, obliquely, to a completely different direction: that of self-discovery and self-celebration. The friable frontier between pleasure and unpleasure remains, however.

8. Reality

The final opposition Wollen (1972) proposed is between fiction and reality. As we have seen, creating a homogenous storyworld presented to us as if seen by a framed window that erases itself as a channel or offers us the illusion of being unaware of its presence creates an easy path to identification and emotional and intellectual closure. On the contrary, counter-narratives will disturb its spectators and readers, pushing towards a critical positioning and not letting go of the idea that we are facing an interpretable and open-ended text as text. Violent Delights, for instance, seems to present a staccato-like opening salvo of several framings that paradoxically erase one another by substitution but also create a cumulative effect... Despite the groundedness of Passe Social and Hoje Não, Matos insists on strategies that make her most specific circumstances present but also forces her readers to negotiate their own positioning in relation to the textual/verbal matter.

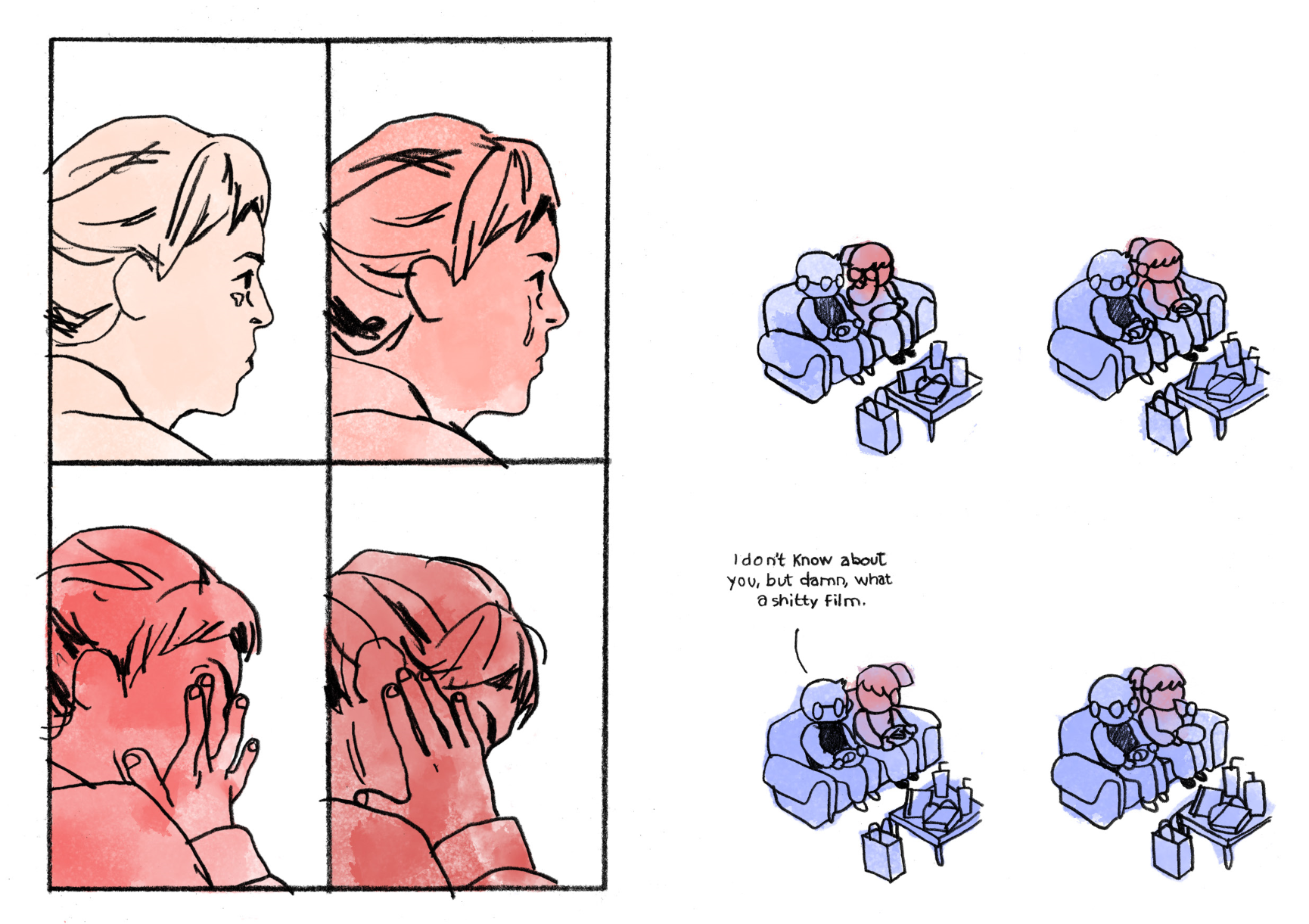

However, the negotiation of fiction and reality in a visual medium does not occur solely at the level of its diegesis, its verbal track. Shifting styles, when not justified by a storyworld resource, is jarring and may alert us to complex negotiations of meaning. Take Joana Mosi’s (2022a) The Apartment. This short book has an impactful exception in its representation choices. As we mentioned, the characters are very simply drawn, with a few lines for their contours. They usually appear with one of two colors, a soft orange and a slightly electric blue, quite probably applied digitally but resulting in a pochoir-like pattern. There is a moment when the male character turns blue (from orange) when he screams across the room to his companion, and at the end, when the female character is reacting to a film they just watched in their living room, her face is red, whereas the rest of her body (as well as surroundings, including her husband) is blue, somewhat like when people blushing are represented in comics. But the greatest discrepancy in style is the page that shows the character crying while watching the movie (Figure 9): we have a page with four panels, separated by a small black filament, showing the character’s profile, drawn in a more detailed style, almost realistic, even though it is also done with simple outlines, and a progressively darker and blottier shade of red. A tear rolls down the character’s face. She wipes it with her fingers.

Source. From The Apartment, by J. Mosi, 2022a, pp. 22- 23. Copyright 2022 by mini kuš!

Figure 9 The apartment

When we spoke above of Hetamoé’s Muji Life, I only mentioned Sianne Ngai’s (2005) “ugly feeling” briefly, but now I can unpack this analysis further, given that to a certain extent, perhaps this is a one-page moment that shows that character’s animatedness. Right at the introduction of her groundbreaking book, Sianne Ngai (2005) points out how animatedness leads “into the passive state of being moved or vocalized by others for their amusement” (p. 32). Obviously, in The Apartment, we are before a little paradox: after all, this flitting, more realistic style could be read as “less animated” than the cartoonish style of the rest of the book, but within its narrative, the contrast acts in such a contrarian way. The sudden access to facial microexpressions embodies the emotional excessiveness, something impossible to accomplish via the chibi style from before and after.

As described, the female character was watching a movie. She cries, and we witness that cry via such radical stylistic transformation. The character’s husband - back to a chibi style - however, seems to have a very different reaction to the same movie, as he says, “I don’t know about you, but damn, what a shitty film” (Mosi, 2022a). This acts in two manners. Not only do we understand that the emotional significance was quite different for the couple - she cries over it, he disparages it - as it sees he does not even acknowledge her tearful reaction (“I don’t know about you”). Or perhaps he is even minimizing it, locking her out of the possibility of communicating emotion. The visual facts we have access to make us believe that they share the same space (the sofa) but are miles apart. There are, along the story, hints at issues that could lead to further spousal scuffles: about the back room, the carpet, the placement of the table, and the ordered food price, but “nothing happens”, to quote an important book by Greice Schneider (2016) on how contemporary comics address the aloofness and feelings of inertia in modern society. The very fact that no melodrama in The Apartment points to a silent yet simmering degradation of this couple’s intimacy. The female character finds an emotional release in the film, a release that literally - even though in the confines of the materiality of the drawn world - animated her into new shapes and gestures and affective-physical affordances. But she will remain locked.

9. In Closing: Animating Meaning-Weaving

It is important to notice here that Ngai (2005) also theorizes animatedness as a “marker of racial or ethnic otherness in general” (p. 94). This, however, will not be a venue for analysis in the present chapter. The three artists I am discussing are all white Portuguese women, which does not imply any sort of “neutrality”. Moreover, we could open a lively discussion about Hetamoé’s use of manga characters and all the vexing issues about their perceived Asianness. These are subjects for another moment.

We could also argue that Joana Mosi’s work has been exploring precisely these sorts of subdued, restrained, almost diluted forms of emotion. The stories I have chosen here never amount to explosive demonstrations of feelings, whether of weepy nostalgia for a lost childhood or the uncanniness of recognizing places the protagonists have never been to before. But those are exactly the affective territories being presented and explored and making up the self-construction of the author’s creative voice.

Mosi presents such complex emotions by putting them into seemingly secure, detached spaces. Hetamoé plunges right into paroxysms and shocking images to coax out grueling but necessary emotions and expose our contradictory personas. And Matos launches complicated multilegibility threads that mirror the multitudinous ways through which we form ourselves. These acts, each after their own complex fashion, create texts that mitigate the impact or disguise the truth of powerful forms of self-identity, but it is their knotted mesh of feelings that, at the same time, allow us to see through and acutely, the very truth they tentatively conceal. In any case, there is no doubt that the authors warrant further explorations on how they explore decentered subjectivities.

Allow me to return to Wollen (1972) once again and to the closing statement of his short yet highly influential text. He writes,

the cinema cannot show the truth, or reveal it, because the truth is not out there in the real world. waiting to be photographed. What the cinema can do is produce meanings, and meanings can only be plotted, not in relation to some abstract yardstick or criterion of truth, but in relation to other meanings. (p. 17)

Comics can produce meanings, and those in Mosi’s, Matos’, and Hetamoé’s comics are finely woven and intricately constructed, both a multitude and a recurring pattern that revisits itself and the selves. It is fragile; it wavers in the wind, but it is ready to trap any new meanings that may come their way.

text in

text in