Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versão On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.7 Braga jun. 2021 Epub 01-Maio-2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.3443

Articles

Cinema, paths and dynamics of co-production with Mozambique: an exploratory look

1 Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

This article provides a brief analysis of the dynamics of co-production between Portugal and Mozambique. It focuses on films financed by the Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual (Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual; ICA) between 2014 and 2020, under the Programa de Apoio ao Cinema – Apoio à Coprodução com Países de Língua Portuguesa (Film Support Programme – Co-production Support with Portuguese-Speaking Countries). In all, 16 films received funding from ICA, and some are still in the production process. Five are co-productions with Mozambican participation – Vovó dezanove e o segredo do soviético (Grandma nineteen and the soviet's secret), by João Ribeiro; Desterrados (The outcasts), by Yara Costa; As noites ainda cheiro a pólvora (The nights still smell of gunpowder), by Inadelso Cossa; O ancoradouro do tempo (The anchorage of time), by Sol de Carvalho, and À mesa da unidade popular(At the table of popular unity), by Camilo de Sousa and Isabel de Noronha. Exploratory documentary analysis (Wolff, 2004) indicates that the currently funded films address themes associated with colonialism and current sociopolitical and cultural events. The Mozambican documentaries, in particular, narrate the struggles for independence in Mozambique, the civil war, but fiction films that are adaptations of literary works by internationally recognized African authors, such as the Angolan writer Ondjaki and the Mozambican Mia Couto, have also been financed.

Keywords: films; coproduction; Mozambique; Portugal

Neste artigo, apresentamos uma breve análise das dinâmicas de coprodução entre Portugal e Moçambique, explorando, em particular, os filmes financiados pelo Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual (ICA) no período compreendido entre 2014 e 2020, no âmbito do Programa de Apoio ao Cinema – Modalidade de Apoio à Coprodução com Países de Língua Portuguesa. Ao todo, 16 filmes receberam financiamento do ICA, estando alguns ainda em processo de produção. Cinco são coproduções com participação moçambicana – Vovó dezanove e o segredo do soviético, de João Ribeiro; Desterrados, de Yara Costa; As noites ainda cheiram a pólvora, de Inadelso Cossa; O ancoradouro do tempo, de Sol de Carvalho, e À mesa da unidade popular, de Camilo de Sousa e Isabel de Noronha. A análise documental exploratória (Wolff, 2004) indica que os filmes financiados atualmente abordam temas associados ao colonialismo, mas também a acontecimentos sociopolíticos e culturais atuais. Os documentários moçambicanos, em particular, narram as lutas pela independência em Moçambique, a guerra civil, tendo sido também financiados filmes de ficção que constituem adaptações de obras literárias de autores africanos reconhecidos internacionalmente, como o escritor angolano Ondjaki e o moçambicano Mia Couto.

Palavras-chave: filmes; coprodução; Moçambique; Portugal

Introduction

In recent years, Portuguese cinematographic policy has focused on supporting the production of films in co-production with Portuguese-speaking countries. Cooperation agreements within these countries date back to the 1980s when Brazil and Portugal signed the first bilateral agreement, Decree-Law No. 48/81, of 21 April (Cunha, 2013). In the last decade, through financial support from the Instituto de Cinema e do Audiovisual (Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual; ICA), the Portuguese government has opened a specific tender for co-productions with Portuguese-speaking African countries. As an eligibility criterion, the proposal must include at least one national producer registered with the ICA and one producer from a Portuguese-speaking country. It should also guarantee the production of an original version in Portuguese.

While there is extensive work on post-colonial Portuguese cinematography (e.g., Macedo, 2016; Pereira, 2016; Piçarra, 2015; Vieira, 2019), few studies have analysed co-productions between Portuguese-speaking countries, the subjects addressed, and the dynamics of co-production, distribution and reception of these works. This research is part of a more extensive study, which seeks to analyse how films co-produced in the last decade represent spaces, migrant subjectivities and experiences of belonging and displacement. What is their potential to mobilise alternative understandings of belonging? How are the imaginaries of everyday lived spaces and subjects' experiences created? How do Portuguese-speaking co-productions evoke the issues of migrations, identities and memory?

This article provides an exploratory documentary analysis (Wolff, 2004) of the films approved for funding under the Programa de Apoio ao Cinema – Modalidade de Apoio à Coprodução com Países de Língua Portuguesa (Film Support Programme – Co-production Support with Portuguese-Speaking Countries; ICA), with particular focus on films co-produced with Mozambique. Besides the documents relating to the funding programme, partnerships, producers' websites and interviews with the directors provided the information on the films, some of which still in production. Whenever they are available, we view the films funded in the period under review (2014-2020).

Cinema in Mozambique: a brief overview

Thinking about recent developments in cinema in Mozambique requires considering the current conditions and the complexity of the political, economic, and social transformations experienced in the past. Colonialism and the wars for independence, and the civil war that followed independence shaped the socio-political and cultural reality of the country and, consequently, the film-making.

Cinema played an important role in representing the liberation struggles, joining support for the political movements that rose to power after independence. After 1975, one of the new government's priorities was creating the Instituto Nacional de Cinema (National Film Institute; INC) of Mozambique, which aimed to qualify Mozambican filmmakers and encourage films focusing on the nation by making educational and militant documentaries. The creation of the INC suggests the political will to produce images to educate the majority of most illiterate populations and communicate political and historical content to a vast and sometimes inaccessible territory (França, 2014; Lopes, 2016; Pereira, 2019).

After independence, there was a significant backlash against polemical pro-colonial representations and attempts to create images of Mozambicans as independent and self-confident, proudly building their own country. The intention was to build a Mozambican identity to overcome ethnic and cultural differences (Fendler, 2014). Since its early days, the INC has sought to record and make known the "new" Mozambique. In 1976, it approved the production of a monthly film. It should capture and analyse local experiences and show them to the rest of the country to learn about them as many Mozambicans as possible. This monthly film was entitled Kuxa Kanema, which means "the birth of cinema"1. Kuxa Kanema "represented a strategic tool to bring information to all Mozambican citizens" (Oliveira, 2016, p. 78), aiming to inform the population. Oliveira (2016) explains that "while before independence there were external productions and initiatives (such as foreign films/productions), in the post-independence period the concern with an image from 'within' became the focus of the political initiative of the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo)" (p. 78). The first documentaries produced with government incentives showcased the people for the people through cinemas and mobile cinemas.

During the first decade of the INC, there were economic agreements with several countries, which provided film, cinematographic equipment and other materials. This investment sparked foreign filmmakers such as Ruy Guerra, who, despite being Mozambican, was based in Brazil, and Licínio Azevedo, a Brazilian who moved to Mozambique recognised as one of the biggest names in Mozambican cinema. Ruy Guerra mobilised several filmmakers to promote technical courses in film training in Mozambique. Guerra became director of the INC and, among other films, he directed Mueda: Memória e massacre (Mueda: Memory and massacre), in 1981, which recreated the historical event in Mueda, in 19602 (Lopes, 2016). Licínio de Azevedo, who had lived in Mozambique since 1975, began working as a journalist, wrote literature and met Ruy Guerra, who invited him to join the INC (Pereira & Cabecinhas, 2016). This filmmaker has explored to this day3 the contexts of war experienced in the country.

There was a tremendous public investment in cinema during this period. Jean Rouch's workshop, in 1978, on the use of Super 8mm, at the University of Maputo, the contribution of Jean-Luc Godard (one of the greatest names in film-making) in the film proposal on the "birth (of the image) of a nation" and a study on the development of national television, are some examples (Lopes, 2016, p. 8).

Cinema produced in Mozambique between the 1970s and 1980s was recognised as a world reference in experimental and revolutionary cinema (Lopes, 2016). Mozambican nationalist politics sought to create a sense of national identity. This approach to cinema as an instrument of communication and ideology had a substantial impact on the development of film production in Mozambique. Even during the war for independence, foreigners were producing films about the liberation struggle. Among them were Venceremos! (We shall win!; 1966), by Dragutin Popovic; Behind the lines (1971), by Margaret Dickinson; A luta continua (The struggle continues; 1972), by Robert Van Lierop, and Étudier, produire, combattre (Study, produce, fight, 1973), by the Cinéthique Group (Lopes, 2016).

Despite the escalating problems stemming from violence and technical problems with production, such as the lack of film and electricity, the INC produced two fiction films in the 1980s (Ferreira, 2016). O tempo dos leopardos (The time of the leopards), by director Zdravko Velimirovic, from 1985, is a co-production with Yugoslavia and O vento sopra do norte (The wind blows from the north), by director José Cardoso, entirely produced in Mozambique. By the time Isabel Noronha joined the INC, the production of the first feature film, invited to participate as the film's production assistant, had engaged directors such as Camilo de Sousa and Luis Patraquim. Isabel Noronha is one of the first Mozambican women film directors. At this time, Sol de Carvalho also returned to Mozambique after studying at the Conservatório Nacional de Cinema (National Conservatoire) in Lisbon. Born in Beira, Sol de Carvalho returned to the country to become director of the National Broadcasting Service of Rádio Moçambique, and work at the magazine Tempo, until he began his career as a director in 1986 (Lopes, 2016; Miranda, 2015).

Any country's first years after independence are times of great hardship, often due to internal disputes, lack of supplies and other issues. Thus, the intense civil war from 1977 to 1992 affected Mozambique, and only in 1994 did the country hold its first multi-party elections. Moreover, infrastructure was lacking for the resumption of cinema, which was only possible through filmmakers, film lovers, and politicians interested in the (re)construction of the new country (Pereira, 2019, p. 306).

Any country's first years after independence are times of great hardship, often due to internal disputes, lack of supplies and other issues. Thus, the intense civil war from 1977 to 1992 affected Mozambique, and only in 1994 did the country hold its first multi-party elections. Moreover, infrastructure was lacking for the resumption of cinema, which was only possible through filmmakers, film lovers, and politicians interested in the (re)construction of the new country (Pereira, 2019, p. 306).

More recently, the Instituto Nacional de Audiovisual e Cinema (National Audiovisual and Cinema Institute; INAC) has focused on the restoration of historical films. Supported by the government and perhaps suggesting a renewed interest in the media, INAC's objectives seem focused on the conservation of historical film. The Portuguese Gulbenkian Foundation supported the launch of this preservation initiative; there were also several official partnerships between INAC in Maputo and the Instituto do Cinema e Audiovisual (Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual) in Lisbon (Convents, 2011, p. 565). In October 2011, it inaugurated the first exhibition with historical documents in Maputo and screened five documentaries. Since then, INAC organises regular film screenings, holding workshops, exhibitions and conferences. It partners with the Mozambican Film-makers Association, Amocine, and the film festivals Dockanema, created in 2006 and held until 2013 in Maputo, and Kugoma, that mainly screens Portuguese-speaking African Countries (PALOP) short films and productions. In general, cinema in Mozambique "remains today committed to social and political issues" (Pereira, 2019, p. 343), relying on external funding for much of its productions.

Co-production with Portuguese-speaking African countries: the case of Mozambique

The audiovisual production of the PALOP, from 1974 to 2015, which focuses on "decolonising minds” through image, has been chiefly accomplished with external funding (Ferreira, 2016, p. 40). “The allocation of foreign funding for fiction feature films amounts to an average of 65%, in the Portuguese-speaking African countries, in the years 1976 to 2013, and 46% in Portugal, that is, almost half of the entire production" (Ferreira, 2016, p. 33). In Mozambique, "65% are transnational feature films, and 50% are Luso-Mozambican co-productions" (Ferreira, 2016, p. 35).

Portugal, which previously had a more European-oriented project, between 1933 and 1949, started to "prioritise the Portuguese-speaking audience in Africa and Brazil" (Cunha, 2018, p. 81). This strategy encouraged cooperation between Portugal, Brazil, Cape Verde, Angola, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea Bissau, and Mozambique, leading to more productions and co-productions.

From the 1970s, the focus of productions changed. They revolve around the independence struggles in Mozambique and the violence suffered by the population during the colonial period. Most of the films are documentaries produced by the Instituto Nacional de Audiovisual e Cinema (National Audiovisual and Film Institute; INAC/INC), some of them in co-production with Blue Art Filmes; and co-productions between RTP, the Rádio e Televisão de Portugal (Portuguese Radio and Television), the Centro Português de Cinema (Portuguese Film Centre; CPC), the first Portuguese film cooperative and the Instituto Português de Cinema (Portuguese Film Institute; IPC), founded in 1971. Among the works produced in this period, the highlights are: Deixem-me ao menos subir às Palmeiras (At least let me climb the palm trees), by the Portuguese director Joaquim Lopes Barbosa, produced and distributed by Somar Filmes in 1973, which was censored and banned until the 25 April 1974 (Piçarra, 2009).

Between 1980 and 1994, the countries signed agreements for film co-production to stimulate film productions and cooperation (Cunha, 2013). Decree No. 33/1989 agreed with Cape Verde, followed by Mozambique (Decree No. 52/90), Angola (Decree No. 12/92) and São Tomé and Príncipe (Decree No. 17/94; Cunha, 2013). These documents define the conditions under which co-productions can be undertaken and financed.

Decree-Law No. 52/90, which regulates the co-production process between Mozambique and Portugal, has as its primary objective to "encourage the co-production of films that, for their artistic and technical qualities, are likely to contribute to the prestige of Portuguese and Mozambican cinema" (p. 5039). This partnership intended to promote the exchange of cinematographic resources and knowledge of both cinematographies. The document sets out the conditions for co-production and the role of the parties in this process. It defines, for example, the technical and artistic participation should be proportional to their financial participation. A critical aspect underlined in Article 17 concerning the reciprocal exchange of information and exchange of publications in the field of cinema. This article also defines the commitment to access the national film catalogues and archives in both countries. This partnership has enabled the co-production and exchange of resources and information over the past decades.

In the 1990s, funding from Instituto Português de Cinema (Portuguese Film Institute) increased film production in Mozambique. However, it still struggled to reach the audiences and competed with the growth of television penetration and soap opera production (Ribeiro, 2018). More recently, thanks to initiatives such as the partnership between the University of Bayreuth, in Germany, and the Eduardo Mondlane University, in Maputo, essential films such as Mueda, memória e massacre (Mueda, memory and massacre) and O tempo dos leopardos (The time of the leopards; 1985) were recovered, digitised and thus made accessible. At the same time, filmmakers of different generations, inside and outside the African continent, delve into colonial, anti-colonial and postcolonial archives, producing and redrawing memories (Monteiro, 2016).

Co-productions within the scope of support to co-production with Portuguese Speaking Countries: the case of Mozambique

In this piece, we analyse specifically the film projects funded under the Programa de Apoio ao Cinema – Subprograma de Apoio à Coprodução Modalidade de Apoio à Coprodução com Países de Língua Portuguesa (Film Support Programme – Co-production Support with Portuguese-Speaking Countries) between 2014 and 20204. This programme is open to independent producers currently registered in the Register of Film and Audiovisual Companies. International co-production projects of fiction feature films, animation shorts and features and documentary films with Portuguese-speaking countries are eligible for this competition.

Projects must involve at least one Portuguese producer registered at the ICA and one producer from a Portuguese-speaking country; a director from a Portuguese-speaking country – included in the list of countries eligible for development assistance from the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). These countries can be "least developed countries", "other low-income countries", and "lower middle-income countries and territories". Furthermore, to be recognised as national production, the projects must meet the nationality criteria. Finally, the production of an original version in Portuguese must be guaranteed. The financial support granted in this competition cannot exceed 80% of the project's total cost (Decree-Law No. 25/2018).

Though the period analysed in this article refers to 2014 and 2020, the programme to support co-productions with Portuguese-speaking countries, promoted by the ICA, dates back to 2007. However, the model did not include the funding to be allocated to productions. In 2013, the model underwent some changes and was renamed Apoio à Coprodução Internacional com Países de Língua Portuguesa (Support for International Co-production with Portuguese-Speaking Countries), and specified the maximum amount to allocate to each type of film. Currently, the competitions set a maximum amount per application for fiction and animation feature films, equal to €450,000, and a minimum amount for documentaries and animated short films of €50,000 (ICA, n.d.-b).

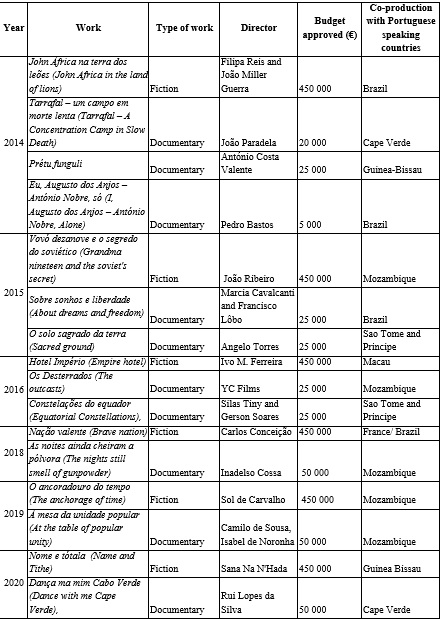

Between 2014 and 20205, 47 film projects submitted to this competition – it approved 16 films. Table 1 shows the films approved for funding. As shown, in the period under analysis, the ICA supported four films co-produced with Brazil, two fiction and two documentaries. John Africa na terra dos leões (John Africa in the land of lions), by Filipa Reis and João Miller Guerra, features Miguel Moreira. The directors had already worked with Miguel on the documentary, Li Ké Terra (2010), which depicts the young man's daily life. Miguel, also known as Tibars or Djon Africa, is the son of Cape Verdeans, born and raised in Portugal, brought up by a grandmother, and never met his father. The film portrays Tibars' journey to Cape Verde, where he hopes to find his father. Inspired by Miguel's true story, this fictional film explores the identity issues of someone who identifies as Cape Verdean, yet is seen as a migrant in Portugal and a tourist in the country he considers his own, Cape Verde. Eu, Augusto dos Anjos – AntónioNobre, só (I, Augusto dos Anjos – António Nobre, alone), by director Pedro Bastos, was released in 2019 as Ambulatório através da poesia de Augusto dos Anjos e António Nobre (Ambulatory through the poetry of Augusto dos Anjos and António Nobre).This film focuses on the life and work of the Portuguese poet António Nobre and the Brazilian poet Augusto dos Anjos. Sobre sonhos e liberdade (About dreams and freedom), by Marcia Cavalcanti and Francisco Lôbo deals with one of the crucial moments in the history of Brazil and its economic and development paths: the abolition of slavery, which took place in 1888. The fourth film in co-production with Brazil (and France) is the fiction film Nação valente by Carlos Conceição. He is a young director from Angola who studied filmmaking in Portugal and was recently awarded the Revelation Award at the Seville European Film Festival (2020) for his film Um fio de baba escarlate (A thread of scarlet slime).

Between 2014 and 2020, two documentaries co-produced with Cape Verde received funding. The documentary Tarrafal – um campo em morte lenta (Tarrafal – A concentration camp in slow death), by João Paradela, premiered in 2017 under the name Tarrafal: Dez Pancadas no Carril (Tarrafal: Ten strokes on the rail) and discusses the traumas caused by the concentration camp, still present in the collective memory in countries like Portugal, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau and Angola. This film won the FICCA Grand Prize for Human Rights in 2018. Dança ma mim Cabo Verde(Dance with me Cape Verde), by Rui Lopes da Silva has been approved for funding in 2020.

Prétu Funguli, by António Costa Valente, was one of the two co-production proposals with Guinea-Bissau approved in the period under review. Pretu Funguli – a Creole expression used with a discriminatory meaning – is a term recovered by the Guinean plastic artist Nú Barreto who transformed it into a plastic concept. António Costa Valente accompanies the artist in Brazil, Guinea-Bissau, Macau, and Paris, where he lives and works, observing his creative process and his reflections on current society. The second proposal approved (in 2020) is the fiction film Nome e tótala (Name and tithe), by Sana Na N'Hada. The director has been working on the photographic archive of Guinea-Bissau. He participates in the collective film Spell Reel (2017), a joint work of Portuguese Filipa César, who compiled the images and created the text that drives the film, with directors Sana na N'Hada and Flora Gomes, among others. This film was part of the forum showcase of the "67th annual Berlin International Film Festival" (2017), in which the director participated, saying:

I am part of the liberation process. I am a farmer, I didn't know about cinema before I went to the struggle. Amílcar Cabral thought that the process had to be documented, we were sent to Cuba and we learned how to handle a camera and a photographic camera. We documented the process as being part of history. I am part of the independence process. So I discovered life and worked in the struggle, in what I could do 6.

As for co-productions with São Tomé, two documentaries were approved for financing, O solo sagrado da terra (Sacred ground), by Angelo Torres, and Constelações do equador (Equatorial constellations), by Silas Tiny and Gerson Soares. The first film is centered on the life and work of poet Alda Espírito Santo, an inescapable figure in the culture, education, and history of São Tomé and Príncipe, which intersects with the process of independence of São Tomé and Príncipe7. The second, narrates the memories of those who lived through the war of secession of Biafra, which sentenced hundreds of thousands of people to starvation in the late 60s of the last century8.

The film Hotel Império (Empire hotel), by Ivo Ferreira, a co-production with Macau, was approved for funding in 2016. Released in 2019, this fiction film tells the story Maria, a young woman of Portuguese origin, who has lived all her life in the Empire Hotel, and who seeks to keep that space, despite pressure from real estate speculators to sell the building9.

As shown in Table 1, among the 16 films approved for funding by the ICA, five are co-produced with Mozambique, the most significant number of films supported per country in the period under review. Two of the five films co-produced with Mozambique with funding from the ICA in the period under review, are fiction films, each with 450,000 in funding – Avó dezanove e o segredo soviético (Grandma nineteen and the soviet's secret), by João Ribeiro and O ancoradouro do tempo (The anchorage of time), by Sol de Carvalho, two prominent players in the history of Mozambican cinema. Both fictional films are adaptations of literary works: João Ribeiro adapted the book with the same name by the Angolan writer Ondjaki and Sol de Carvalho's adaptation of Mia Couto's A varanda do Frangipani(The balcony of Frangipani, 1996).

The fiction film Avó dezanove e o segredo do soviético (Grandma nineteen and the soviet's secret), by directorJoão Ribeiro, was the only Mozambican film approved in 2015. A co-production between Portugal, Mozambique and Brazil with an ICA approved budget of €450,000. A film produced by the Portuguese production company Fado Filmes, the independent Mozambican production company Kanema Produções and the Brazilian production company Luz Mágica. Later, the film also received funding from Agência Nacional do Cinema do Brasil (Brazil's National Cinema Agency), Ancine (2016, with the production company Grafo Audiovisual, for R$500,040.00, around €79,000). The film stems from on Ondjaki's childhood memories, in Luanda in the 1980s. It explores children’s perspective during the construction of the mausoleum of Agostinho Neto, first president of the Republic of Angola, in the Praia do Bispo district, built with Soviet support. The boy lived with his grandmother, who lost a finger and became "grandma nineteen" because of her 19 fingers. The film premiered at the "Pan-African Film Festival" in the United States in February 2020. It received the best film award at the "Black International Cinema Berlin", Kisima Music and Film Awards, in Kenya, for best direction and best supporting actress for Ana Magaia and best feature film at the "7.ª Edição do Festival Internacional de Cinema da Praia" (7th Edition of Praia International Film Festival), Plateau, in Cape Verde10.

O ancoradouro do tempo (The anchorage of time)11, by director Sol de Carvalho is, as already mentioned, an adaptation of the book A varanda do Frangipani (The balcony of Frangipani) by Mia Couto, who co-wrote the script, and a co-production between Angola, Mozambique and Portugal by Real Ficção and ProMarte. The film, approved in 2019, was granted a €450,000 fund from the ICA and a €30,000 support from the Berlinale World Cinema Fund. The story's plot is about a police investigation of a crime committed in a former colonial fortress converted into a nursing home. Upon the nursing home director's murder, everyone confesses to having committed the crime, both the elderly and the staff, for all sorts of reasons. The film is currently in production.

The three other films approved for funding are documentaries. Two of these works by young directors with promising careers in the Mozambican cinematographic scene: Yara Costa and Inadelsso Cosa. Os Desterrados (The outcasts), by Yara Costa, approved in 2016 in co-production between Real Ficção and YC Films, had a budget of €25,000. of the families descendants of Portuguese king D. Carlos and the emperor of Gaza in Mozambique, Gungunhana. Gungunhana's great-granddaughter lives in Lisbon, and a grandson of king D. Carlos I, the king who ordered Gungunhana's arrest, lives in Mozambique, where he was born, where he is known as Buffalo. For the director, "both the descendants of the kings are contemporary consequences of a common colonial past12. The film As noites ainda cheiram a pólvora (The nights still smell of gunpowder), by Inadelso Cossa, is about contemporary Mozambican reality and the effects of the Civil War on society. The Mozambican director participated in Berlinale Talents, and was interviewed for the documentary Cinema as resistance – Filmmakers who want to change the world (2019), by Deutsche Welle. Cossa, sets out to address how the war has been a silenced theme. It is a sequel to the short film Karingana – Os mortos não contam estórias (Karingana – The dead tell no tales; 2018), about a filmmaker who returns to his native village and finds a community traumatised by war. The following approved documentary, in 2019, À mesa da unidade popular (At the table of popular unity), is a project by directors Camilo de Sousa and Isabel Noronha and is still in production. Camilo de Sousa left Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) in the early 1970s and joined the Frelimo guerrillas. First at the Nachingwea training base and then in the national liberation struggle. He currently lives in Portugal and has directed several films, including Sonhámos um país (We dreamed a country; 2019), with Isabel Noronha. In this film, the director returns to Mozambique to reunite two comrades in arms. With Aleixo Caindi and Julião Papalo, he recalls the joy of liberation and the difficult times experienced33.

Final remarks

From 1974 to 2015, most audiovisual production in the PALOP countries has resorted to external funding (Ferreira, 2016). The Film Support Programme – Co-production Support with Portuguese-Speaking Countries was one of the initiatives for funding co-productions, having received 47 proposals in the period between 2014 and 2020. Of these 47 proposals, it financed 16 films, five of them in co-production with Mozambique. Many of the co-productions "scrutinize colonial history, which includes colonialism, the struggles for independence, and civil wars" (Ferreira, 2016, p. 39). For Ferreira (2016), cinema can play a central role in decolonizing the gaze when used to develop a critical perspective on colonial and civil war history and memory. The "decolonization of the mind" is, according to Lopes (2016), "both a prerequisite for successful Mozambican cinema and also the theme of a serious Mozambican cinema" (pp. 27-28). This is precisely what the young Mozambican filmmakers Yara Costa and Inaldeso Cossa do in the documentaries Desterrados (The outcasts) and As noites ainda cheiram a pólvora (The nights still smell of gunpowder). They address the colonial period and its effects, particularly the Civil War, in today's society. Indeed, "slavery, colonialism, neo-colonialism, and racism have been present throughout the history of Mozambican society" (Lopes, 2016, p. 28) and these experiences are reflected in part of the current film production. Furthermore, Avó dezanove e o segredo soviético (Grandma nineteen and the soviet's secret), by João Ribeiro, and O ancoradouro do tempo (The anchorage of time), by Sol de Carvalho, are adaptations of literary works by the Angolan writer Ondjaki and the Mozambican writer Mia Couto, revealing the importance attributed by Mozambican film-makers to African literature.

It is essential to deepen this analysis by exploring the economic factors that influence film-making in Mozambique, as well as other funding programs that support co-production proposals with PALOP countries. In future research we will try to understand how countries like Mozambique, for example, view cinema today and what initiatives they have undertaken to support Mozambican film production.

Acknowledgements

This article is funded under the "Knowledge for Development Initiative", by the Aga Khan Development Network and the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, IP (nº 333162622) in the context of the project "Memories, cultures and identities: how the past weights on the present-day intercultural relations in Mozambique and Portugal?". This work is also supported by national funds through the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020.

REFERENCES

Cardoso, M. (2003). Kuxa Kanema – O nascimento do cinema [Filme]. Dérives; Lapsus; Filmes do Tejo. [ Links ]

Convents, G. (2011). Os moçambicanos perante o cinema e o audiovisual: Uma história político-cultural do Moçambique colonial até a República de Moçambique (1986-2010). Edições Dockanema/Afrika Film Festival. [ Links ]

Cunha, P. (2013). Coproduzir em português: Da política e da prática. In S. Dennison (Ed.), World cinema: As novas cartografias do cinema mundial (pp. 75-88). Papirus Editora. [ Links ]

Cunha, P. (2018). Portugal e Moçambique: Cooperação e co-produção cinematográfica no pós-independência. In J. Seabra (Eds), Cinemas em Português. Moçambique – Auto e heteroperceções (pp. 81-100). Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. [ Links ]

Decreto-Lei n.º 25/2018, Diário da República n.º 80/2018, Série I, nº. 25 (2018). https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/115172414/details/maximized [ Links ]

Decreto-Lei n.º 52/90, Diário da República n.º 284, Série I (1990). https://www.ica-ip.pt/fotos/editor2/o_que_fazemos/protocolos_e_acordos/dec52-90.pdf [ Links ]

Fendler, U. (2014). Cinema in Mozambique: New tendencies in a complex mediascape. Critical Interventions, 8(2), 246-260. https://doi.org/10.1080/19301944.2014.940245 [ Links ]

Ferreira, C. O. (2016). O drama da descolonização em imagens em movimento – A propôs do “nascimento” dos cinemas luso-africanos. Estudos Linguísticos e literários, 53, 177-221. http://dx.doi.org/10.9771/2176-4794ell.v0i53.16120 [ Links ]

França, A. (2014). O cinema moçambicano pós-colonial: outros olhares, outros discursos. Revista Crioula, (13). https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1981-7169.crioula.2013.64732 [ Links ]

Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual. (s.d.-a). Comboio de sal e açúcar | train of salt and sugar. http://icateca.ica-ip.pt/filme/COMBOIO+DE+SAL+E+ACUCAR/2002 [ Links ]

Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual. (s.d.-b). Coprodução com Países de Língua Portuguesa. https://ica-ip.pt/pt/concursos/apoio-ao-cinema/2021/coproducao-com-paises-de-lingua-portuguesa/ [ Links ]

Lopes, J. S. M. (2016). Cinema de Moçambique no pós-independência: Uma trajetória. Rebeca-Revista Brasileira de Estudos de Cinema e Audiovisual, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.22475/rebeca.v5n2.223 [ Links ]

Macedo, I. (2016). Os jovens e o cinema português: A (des)colonização do imaginário? Comunicação e Sociedade, 29, 271-289. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.29(2016).2420 [ Links ]

Miranda, M. G. (2015). Cinema africano em foco: Entrevista com o cineasta Sol de Carvalho. Mulemba, (1), 21-28.https://doi.org/10.35520/mulemba.2015.v7n12a5020 [ Links ]

Monteiro, L. R. (2016). África(s), cinema e revolução. Buena Onda Produções Artísticas e Culturais. http://buenaondaproducoes.com.br/pdfs/CATALOGO_AFRICAS.pdf [ Links ]

Oliveira, E. A. (2016). Cinema moçambicano – Imagens de guerra, imagens “sobreviventes”. Revista Monções: Revista de Relações Internacionais da UFGD, 5(10), 64-89. [ Links ]

Pereira, A. C. (2016). Alteridade e identidade em Tabu de Miguel Gomes. Comunicação e Sociedade, 29, 311-330. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.29(2016).2422 [ Links ]

Pereira, A. C. (2019). Alteridade e identidade na ficção cinematográfica em Portugal e em Moçambique [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade do Minho]. RepositóriUM. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/65858 [ Links ]

Pereira, A. C., & Cabecinhas, R. (2016). “Um país sem imagem é um país sem memória…” – Entrevista com Licínio Azevedo. Estudos Ibero-Americanos, 42(3), 1026-1047. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-864X.2016.3.22989 [ Links ]

Piçarra, M. C. (2009). Portugal olhado pelo cinema como imaginário de um império: Campo/contracampo. Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, 3(3), 164-178. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS332009303 [ Links ]

Piçarra, M. C. (2015). Azuis ultramarinos. Propaganda colonial e censura no cinema do Estado Novo. Edições 70 [ Links ]

Ribeiro, J. (2018). Cinema e televisão. In J. Seabra (Eds), Cinemas em português. Moçambique – Auto e heteroperceções (pp. 47-52). Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. [ Links ]

Schefer, R. (2020). Mal de arquivo: Uma aproximação ao arquivo anti-colonial moçambicano a partir da obra de Ruy Guerra. Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, (special issue), 52-72.https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS0001816 [ Links ]

Vieira, T. (2019). Inscrevendo as ruínas da descolonização e dos mecanismos de poder na imagem fílmica: O cinema de Pedro Costa. Vazantes, 3(1), 152-165. http://periodicos.ufc.br/vazantes/article/view/42919 [ Links ]

Wolff, S. (2004). Analysis of documents and records. In U. Flick, E. von Kardorff, & I. Steinke (Eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp. 284-289). Sage. [ Links ]

Notes

1In this regard, see the documentary by Margarida Cardoso (2003), Kuxa Kanema - O nascimento do cinema (KuxaKanema, the birth of cinema), which recalls the history of the cinejornal and the INC..

2The film reconstructs the Mueda massacre (1960). According to Schefer (2020), "Guerra documents a collective carnival Maconde reconstitution, almost entirely autonomous from the film, of what is seen as one of the most important episodes of resistance against Portuguese colonialism in the second half of the twentieth century” (p. 62).

3The more recent film, 2016, Comboio de sal e açúcar (Train of salt and sugar), for example, deals with hundreds of people crossing from Nampula to Niassa in the middle of the civil war (the film is set in 1988), to trade salt and sugar in Malawi (ICA, n.d.-a).

4It should be noted that there are other co-productions financed by the ICA and by other entities within the scope of other calls for tender and funding programmes. Co-produced films such as Operação Angola: Fugir para lutar (Codename Angola: Escape to fight; 2015), by Diana Andringa, was produced in a joint Portuguese-Mozambican co-production, with funding from the ICA and the Lisbon City Council; the film Comboio de sal e açúcar (Train of salt and sugar; 2016), by Licínio de Azevedo, is a co-production between Portugal, Mozambique, France, Brazil and South Africa, with funding from the ICA, Ibermedia and Visions Sud Est, as well as the film Joaquim (2018), by Marcelo Gomes, produced by Ukbar filmes, a Portuguese-Brazilian co-production.

Received: June 01, 2021; Revised: June 16, 2021; Accepted: June 16, 2021

texto em

texto em