Cossa, I. (Director). (2017). A memory in three acts [Film]. 16mmFILMES

This review communicates a cultural vantage point of theories that articulate with the unfolding of a documentation told by voices who once could not speak during the acts of colonization, violence, and atrocious memories in colonial spaces. It is that of a documentary of lived experiences during the Portuguese colonialization period in Mozambique that Inadelso Cossa realized, photographed, and directed within A memory in three acts (2017). To establish a critical analysis of this documentation, the methods used to inaugurate the critique come from authors that collectively elaborate this concept of reaching consciousness in theory. Social justice and the city of David Harvey (2009) (a geographer), Society of the spectacle of Guy Debord (1970) (a revolutionary thinker), and Regarding the pain of others of Susan Sontag (2003) (a filmmaker) form a manifestation position, in their writings to express an association with contexts in social injustice and un-humanitarian situations. Though the conceptual elements used to analyze A memory in three acts come from an occidental reflection of various contexts, their contribution to analyzing critical concerns in a global view come from their standpoints in social activism for human rights and is considered a self-reflexive way to perceive other realities.

In the search for archival material, the commemorative documentary unfolds. The director who is a Mozambican, begins to narrate a story from another time that he had not experienced (MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology, n.d.). He expresses with his own voice a moral obligation to investigate the true, original history told by those who underwent the repression and cruelty of a certain period, the Portuguese colonization of Mozambique. In the documentary, three principle characters are introduced to narrate their lived experience through the Portuguese colonization of Mozambique. To contextualize the dialogue that individually took place with these three characters, the direction of the film adapted this sequential structure to construct a memoir that starts with a prologue and ends with an epilogue. Having similar moments to share throughout the three acts, the documentary evokes a memorial essence to it. These moments coincide and superimpose as the three characters’ involvement in this cinematic piece is a tri-parts plot merged within the acts to develop; an orientation of the other (their background, formal presentation), records of events, recordings of events, and re-orientation (the closure that was brought about by a suppositional testimonies/statements) that ended with a seemingly open scene – suggesting continuation or a sequel to the documentary.

The first scene of the prologue starts with an image of a Portuguese flag scaling and taken down through a ceremony, on the 25th of June, 1975, the day Mozambique became independent from the Portuguese colonization. Montages of videos, expressing polarities, Mozambican children marching, people of all ages manifesting and celebrating on foot, asking for a new country, a utopic dream that seemingly was hard to attain, contradicted with the Portuguese higher class driving cars. The PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado [International and State Defense Police]) repression, the oppression, that lead to the liberal movements, resulted in an educational and institutional gap, the director states. Education is the biggest question that was posed. Historical education, here, is about the clandestine resistance, the resistance of the people who believed in their freedom to live normally like in any other free country. On the subject of misrepresenting part(s) of history in education, the situationist Debord (1970) in “The proletariat as subject and representation” perceives ideology – a referential system of history – as an expression of history that is manipulated through power. Meaning that the consequence of this capitalist, ideological act is a “historical social system” (Debord, 1970, p. 60)1 that affects the proletariats2, a social class that depends on labor to live. In the case of Mozambique during colonization, the proletariat class required substantial and excessive working power brought about by force. At that time, this class’ worker status consisted of involuntary servitude, an unfree labor upon where individuals had no choice in accepting or denying the forced manual overwork in order to strive and be able to survive in their own land. By relating the Mozambican individuals that endured servitude to the proletariat class, the Debordian theory of social classification in relation to injustice and exertion of power towards the proletariat class expresses the transition and delineation between slavery and capitalism. The proletarian ideology in this case is to project and distinguish between the servitude during the colonization period and the capitalist-leading factors that made this servitude of the Mozambican individuals transpose to become the most evident harsh situation of the (forced) working class. Debord, however, stands with the proletariats, as they mark the modern human history with their revolutionary movements in opposition to injustice. His humanist actions and words against the consequential, malevolent capitalism and the exertion of power upon these individuals is paraphrased by Debord’s consistent efforts to project these sensitive, important happenings in society and the modern global world through his provocative (awakening) theoretical reflections.

Moreover, on the other hand, the bourgeoisie class, the colonial power, perceives the originality of history where it “came to power because it was the class of the developing economy” (Debord, 1970, p. 45), as well as, the class of developing power. That is to say, that the selection and disregarding of historical moments in time that tend to outshine a specific policy and ideology lead to the point of discrimination. Hereby the idea of discrimination done against the Mozambicans by the Portuguese colonies rooted from forced and forged teachings, from obligating a missionary education system, which at different moments, contradicted their claimed teachings, to unanswerable behaviors that brought confusion upon the Mozambicans by the forced system. By speaking of discrimination, the ideology of it, as a separator between two positions an antagonist and protagonist-one that discriminates and the other that gets discriminated. It is not an act of victimization, per se, rather it is a self-sustained act of injustice superiority that creates more confusion than simplifies critical situations. In the case of the three characters with whom Cossa dialogued, discrimination started since a very young age. It firstly appeared as a compulsory performance of labor recruitment ordered by the colonialists and the political administration to project superiority and dominance of a higher power upon a lower one. But that was not the sole outcome of this discrimination, as the economic system, the system of the capital, had to do with this superiority as well. Colonialism as a pseudo-socialist reflection of what seems to be perceived as a superior guidance and assistance into the other’s context and land, state the contrary. This pseudo-socialist reflection provoked other injustice acts to appear, as Cossa divides his investigation into three acts with the three characters expressing recollected moments of similar events, experienced at the same period.

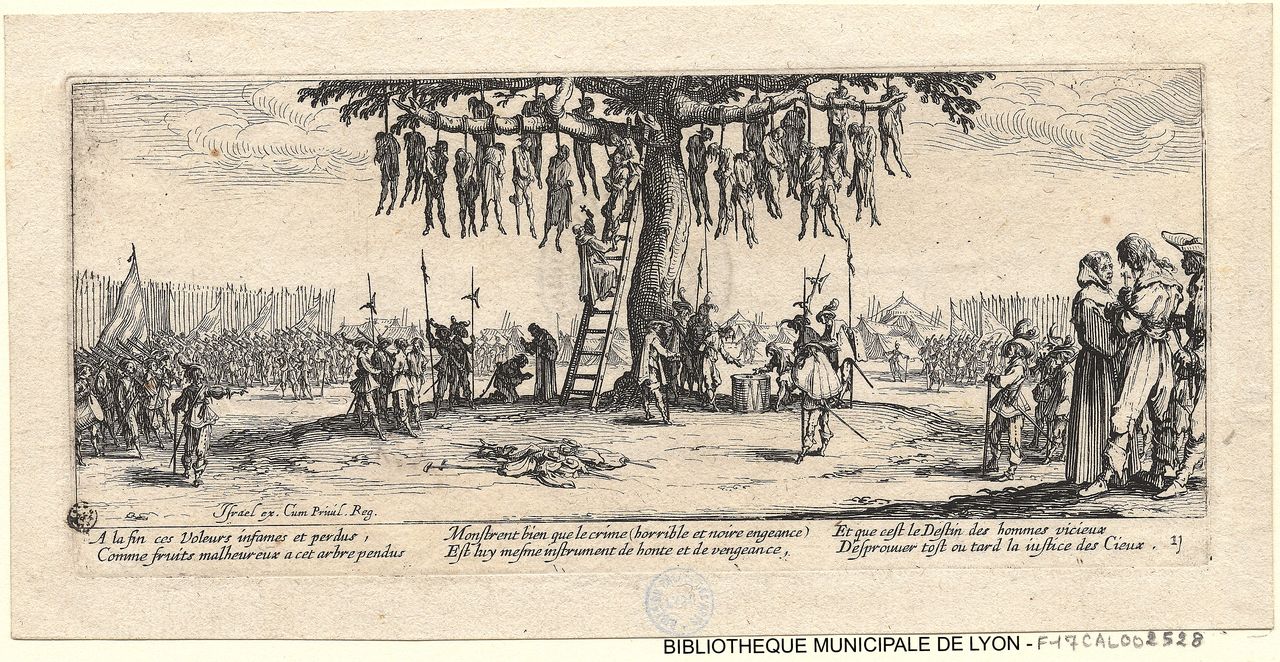

A memory in three acts is assembled with the superimposition of “the colonist ghost”, “the memories of violence”, and “among the ruins of a memory”, the three acts, that bring a very loud ambiance of recollection and remembrances. Cossa’s strong relation to the subjects of the clandestine resistance and the PIDE repression verifies his position as a Mozambican. His positioning as the first narrator that spoke during the film, also is an actual mergence to the subjects of that colonial period, serving his recognition memory to be not only that of the recollection of investigated historical material but also that of the very core meaning of his familiarity to these subjects. He familiarizes to the context, as he familiarizes to the pain of others, which could be very overwhelming at times. According to Sontag (2003), images acquainted to the pain of others, the representation of moments of cruelty, must have conditions to be demonstrated as so. She expresses, “perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it (…) or those who could learn from it” (Sontag, 2003, p. 34). Sontag (2003), thus, explores through iconography the critique of the image, as a spectacle and the audience (without having the former mentioned conditions) that sees the image as spectators, as shown in Les miseres et les malheurs de la guerre by Jacques Callot in 163333 express this relation between the spectacle and the image.

Figure 1 Les miseres et les malheurs de la guerre by Jacques Callot (1633) Source: https://numelyo.bm-lyon.fr/f_view/BML:BML_02EST01000F17CAL002528

Figure 2 A real captured violent scene in Mozambique during the colonialization period. The spectators here are us, theviewers of the documentary (A memory in three acts, 2017) Source: Cossa, 2017, 25:12

Figure 3 A real captured violent scene in Mozambique during the colonialization period. The spectators here are us, theviewers of the documentary (A memory in three acts, 2017) Source: Cossa, 2017, 25:18

By remembering flashbacks of personal encounters and stories that have been told, the critique of the image expresses the significance of power the image withholds. The image as it is visualized, it evokes the modality of the sight to observe then perceive what the image tries to deliver. Cossa, here, constructs a montage of images and videos that superimpose with the sequence of the plot, the words of the narrators, and the silence during the documentary (a separation between the image and the actuality). To articulate the storyline, the director chooses clips to express realities in specific occurrences, as the following: vigilance and control such as the use of binoculars, the act of bullfighting4, and the recording machine, then there are the clips with architectural spatial importance: simulating an interrogation room, towering edifices, colonial prison (a current private school), the PIDE building (Vila Algarve); to those that were part of the colonial period: clandestine resistance (mobilized elements), PIDE agents and police, and Chico Feio (the Mozambican villain that tortured Mozambicans in the PIDE building during their custody), to give the reader a pause to rethink of the urban system that affects the social justice during the colonization period. Harvey (2009) in “Liberal formations” sees that “social space, therefore, is made up of a complex of individual feelings and images about and reactions towards the spatial symbolism which surrounds that individual” (p. 34), constructing a geometric system of memories affected by lived experiences. The colonial prescriptive territoriality and the revolutionary movements of the proletariats since the clandestine resistance, stem from the morality and the consequence of human practice in social justice that always circle around the question of space. As one of the three interviewed narrators in the documentary demands that the private school, which once was a place of torture and death, to return to the state. Because, after all this suffering, then the memory of the dead Mozambicans, those who were left blind and disabled, this building should return to the Mozambicans. It is a call for giving people back their history, their identity. “Proletarian revolution is this critique of human geography through which individuals and communities could create places and events commensurate with the appropriation no longer just of their work, but of their entire history” (Debord, 1970, p. 99).

In Inadelso Cossa’s effort of exploring the colonial Mozambique by exposing metaphors, symbolisms, and posing many question marks, the utopia of a new country, is his own ideal of constructing a historical originality is to be built by the people (Mozambicans) to the people (Mozambicans). His words, his message, his objective in mediating the truth does not come out from his patriotism, but from the inner human that seeks social justice for the Mozambican history. Such dedication to a cause is part of the memory, representation and identity summed in one piece of an artistic montage that gives awareness, shares pain, and invites the viewer to rethink of how human actions have a large impact on the lives of people and their history.

text in

text in