Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versão On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.8 Braga dez. 2021 Epub 01-Maio-2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.3621

Articles

Hans Erdmann’s Music in the Film Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Friedrich Murnau, 1922)

1 Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual e Publicidade, Facultade de Ciencias Sociais e da Comunicación, Universidade de Vigo, Vigo, Espanha

2 Centro Musical LIRA-San Miguel de Oia, Vigo, Espanha

The text focuses on the study of the musical soundtrack by the composer Hans Erdmann, made for the German film Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu, the Vampyre; 1922) by the director Friedrich Murnau. Its methodology combines the qualitative technique of case studies with the latest trends in the musicological analysis of film soundtracks. Research shows the stylistic elements, structural resources, musical influences, references to composers and the instruments used in this musical composition. The romantic creation by Erdmann also has influences of baroque style, classicism, and impressionism. It constitutes an innovative contribution in the area as musical and film studies of the nature that is presented in this contribution cannot be easily found.

Keywords: cinema; music; German expressionism; Nosferatu, the Vampyre; Hans Erdmann

Este artigo centra-se no estudo da banda sonora musical do compositor Hans Erdmann, feita para o filme alemão Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu, o Vampiro; 1922) pelo realizador Friedrich Murnau. A metodologia combina a técnica qualitativa do estudo de caso com abordagens recentes na análise musicológica de bandas sonoras de filmes. Esta investigação destaca os elementos estilísticos, recursos estruturais, influências musicais, referências de compositores e orquestração instrumental da partitura. A criação romântica de Erdmann é também influenciada pelo estilo barroco, classicismo e impressionismo. Este artigo constitui um novo contributo na área, uma vez que não foram encontrados estudos musicais ou cinematográficos com o tratamento aqui oferecido.

Palavras-chave: cinema; música; expressionismo alemão; Nosferatu, o Vampiro; Hans Erdmann

Introduction

Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu, the Vampyre; Friedrich Murnau, 1922) is still recognised 100 years later as the most representative film of the genre and German expressionism for its narrative and aesthetic value. Studies on the era’s cinema are plentiful when it is approached from the fantasy horror genre and the vampire theme. However, the contributions decrease when the research focuses on its music, and are scant when the study of the soundtrack and score is included. This shortcoming is due to structural circumstances, since we are dealing with a silent film released with live music, whose original score is lost and was subsequently showcased with works from the classical cast, the deterioration of the celluloid over time that has led to various restorations and, above all, the preference in audiovisual research for studying the imagery rather than the musical soundtrack; circumstances that have diminished the expectations of undertaking its study from the perspective of musicology. A contribution from the entity that is presented is timely at this current time close to the centenary.

Framework

Although there are no antecedents on the vampire theme in the history of silent film (González, 2008; González Hevia, 2012; Peña Sevilla, 2000), it is Friedrich Murnau’s film that is made in the midst of German expressionism. This film is not only influenced by this movement, as it also draws on other cultural references (Rubio, 2005) such as romanticism, Kammerspiel, fantasy literature, gothic novels, and expressionist painting.

With regard to the work of Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe (known as Friedrich Murnau) and Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens there have been significant contributions from different approaches, of which the studies of Berriatúa (1990a, 1990b, 2001, 2009), Berriatúa and Pérez (1981), Bouvier and Leutrat (1981), Eisner (1964, 1955/1996), Jameux (1965), Kracauer (1947/1985), Patalas (2002), Sánchez-Biosca (1985, 1990) and Tone (1976) stand out. But, when approached from the musicology, the research is limited, although what stand out are the works focused on the reconstruction of the film’s original score (Gillian Anderson, n.d.; Heller, 1984; Müller & Plebuch, 2013), contributions on the function that music fulfilled in the cinema of the silent era (Altman, 2007; Anderson, 1988; Marks, 1997; Tieber & Windisch, 2014), those specific to soundtracks in expressionist films (Amorós & Gómez, 2017, 2018) and compilations on music in horror movies (Hayward, 2009; Lerner, 2009); in addition to more general studies focused on the functions of music in films (Colón et al., 1997; Navarro Arriola, 2005; Valls & Padrol, 1986); on sound and soundtracks in films (Chion, 1982, 1990/1993, 1995/1997); the significance of baroque, classical and romantic composers in the uses of film music (Lack, 1999); the rhythmic and aesthetic functionality of soundtracks in films (Nieto, 2003; Torelló, 2015); as well as more conceptual approaches around nuances in the musical and film analysis (Fraile, 2007; Lluis i Falcó, 1995); or on the use of classical music with expressive and/or imitative purposes (Olarte, 2004, 2008).

At the premiere of Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Berlin, 4 March 1922), the live audition of the musical soundtrack created by Hans Erdmann (Berriatúa, 2009, p. 307) took place for the only time, with O. Kernbach (Deutsche Kinemathek, 2003) as the conductor. The original score was lost and for a time it was showcased with classical repertoire music. Decades passed until its reconstruction thanks to the archive of documents from the period (García Merino, 2016, pp. 7–8; Navarro Arriola, 2005, p. 56), such as Erdmann’s Fantastisch-romantische Suite (1926), the compendium of compositions for silent film Allgemeines Handbuch der Film-Musik (produced by Erdmann, Becce and Brav in 1927) and the musical critique of the German press of the time.

Recent studies on this soundtrack focus on the reconstruction of Erdmann’s score (García Merino, 2016, p. 8): with the work of the composer Berndt Heller (1984), whose version preserves the 40 minutes of original music, repeating parts and adding repertoire pieces and opera adaptations; the contribution of Gillian Anderson and James Kessler (Gillian Anderson, n.d.) that condenses the music into 40 minutes, incorporating repetitions and material of their own creation; and the version by Janina Müller and Tobias Plebuch (2013), creators of the term “modular forms”, to fit different fragments, varying instrumentation, dynamics, tempo, duration, character and function

The study of Hans Erdmann’s composition for Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens by Friedrich Murnau arouses interest in film research, due to the wealth of nuances that the score offers in synergy with the film’s imagery.

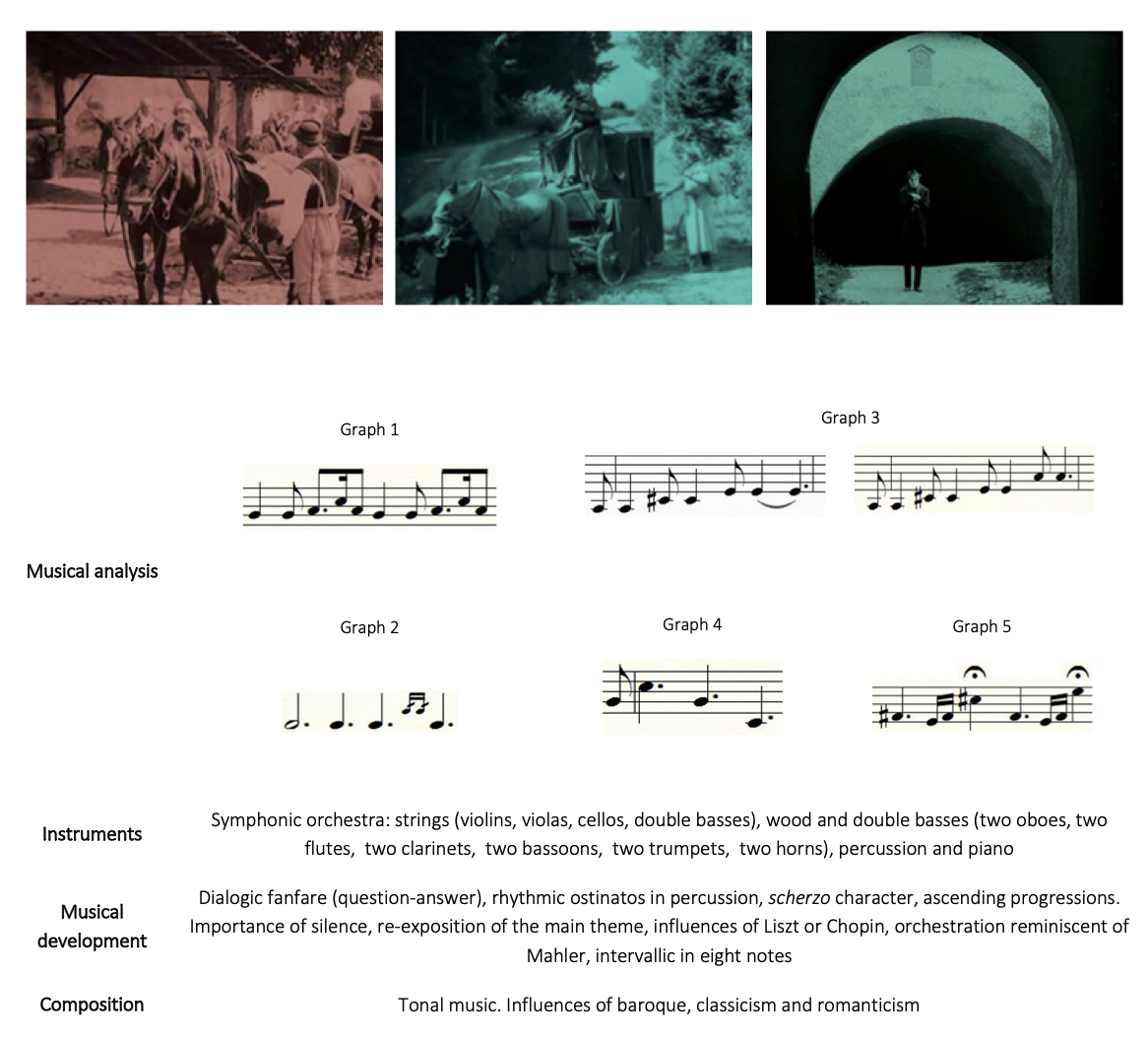

Materials and Methods

The film has been restored on occasions; there is the black-and-white tape (Berriatúa, 2001), the sepia version by Enno Patalas (Munich, 1984) and later another has been made according to the colour tinting of the era. The colour version (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung Foundation, 2005/2006) is made with material from the Spanish Film Library, the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv (Berlin), the French and Bologna Cinematheque and the collaboration of Luciano Berriatúa, a specialist in his work (Berriatúa, 2009, p. 275–313). This version, with original music by Hans Erdmann and a reconstructed score by the Austrian Berndt Heller (1984), is the material used in this contribution (Table 1).

Methodologically, the analytical and qualitative (Stake, 2007), and descriptive and hermeneutical (Ashworth, 2000) case study is chosen. In the structural analysis of the composition (Riemann, 1928) other qualitative methods are used that focus on the latest guidelines in musicology for film soundtracks (Tagg, 2012). The subject of study focuses on analysing music in accordance with the visual elements of the film imagery (Casetti & Di Chio, 2007), delving into an analysis of the soundtrack, stylistic and aesthetic resources, sound contrasts, design of musical motifs and phrases, in correlation with the technical and narrative elements of the imagery, contemplating the diversity of instrumentation in the score, direct musical influences and indirect musical movements in its creation and references to the musical style of renowned composers in musical history.

Erdmann’s Music in Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens

The composer Hans Erdmann Timotheus Guckel (Breslau 1887-Berlin 1942) joined the recently created German production company Prana-Film (1921, producer Enrico Dieckmann and designer Albin Grau) taking charge of the musical section after his career as a musician for theatre (García Merino, 2016, p. 11). His tenure would be brief and he only composed the soundtrack of this film, since a series of circumstances forced the studio to close, such as Murnau being accused of violating the copyright of the novel Dracula (Bram Stocker, 1897), the lawsuit filed by the writer’s widow, and this lawsuit resulting in an unfavourable ruling that ordered significant compensation and the destruction of negatives and copies of the film; all this caused the studio to declare bankruptcy. Despite the incident, Erdmann continued his musical career linked to film (García Merino, 2016, pp. 5–6) composing for other directors (Fritz Lang, Paul Wegener), as professor of film music at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory (Berlin), musical critic and founder of Gefima (a society that defended the copyrights of film composers).

In his first opera for Prana, Erdmann composes a symphonic work that runs harmoniously with Murnau’s aesthetics. The film tells the story of a real estate employee (Jonathan Hutter) who travels to the Carpathians to purchase a property acquired by a count (Orlok) who is a vampire (Nosferatu). Strange things happen to him there. After closing the sale, he returns to his city and Nosferatu follows him, travelling by boat to his new residence hidden inside coffins with terrifying rats. On the way the crew mysteriously die, and on arrival the rats spread like a hapless plague throughout the city. The vampire’s mansion is close to the home of Hutter and his wife (Ellen). A powerful fatal attraction arises between Nosferatu and Ellen.

Musically, it is divided into five acts that correspond to the different parts of the story, imitating the symphony form with different movements1. The film’s subtitle adds the statement “symphony of horror”, emphasising the influence of the soundtrack on the film narrative to generate an emotional climate (Berriatúa, 1990b, p. 394). To highlight the film’s atmosphere, Erdmann creates a score with influences from romanticism, but also drawing on other styles (baroque, classicism, and impressionism). It is an approach that distances itself enormously from musical expressionism, and that is more in line with the production’s film era.

The composer opts for a large-format programme symphony (Grout & Palisca, 2002, p. 734), created around a descriptive, literary theme, lending a hand to musical classicism. Formal structures are abandoned with an exposition of motifs developed from a central musical idea that serves as a leitmotif (Adorno, 2008, pp. 46, 94). In his creation he opts for a symphonic orchestration, with a wide variety of instrumentation to enrich the film text, associating the scenes with a certain music, relating characters to specific musical pieces (Wagner leitmotif), and expressing certain situations, not only with the imagery but also with the music and the use of certain instruments. Furthermore, the composer handles the musical silences sublimely (Román, 2017, pp. 65–68) with poetic purpose.

Erdmann’s music is integrated with Murnau’s imagery, musical landscapes in the form of disturbing preludes to unravel the identities and subconscious of the characters (Neumeyer & Buhler, 2001), their psychology, feelings and behaviours, the various locations (real landscapes and of the subconscious), different atmospheres (shades and shadows of expressionist lighting), connoted staging (character costumes, props) and the different colour tints in the frames with symbolic value (sepia for the light of dawn, ochre at dusk or indoor light, dark blue for night-time outdoors), elements that help create an emotional state in the viewer.

Various musical styles flow through the film imagery, and the development and reference to pieces by renowned composers is perceived. Hutter’s awakening at the inn is accompanied by the timbre of woodwinds and violins that, with their ornamental expressive singularity, identify dawn and the sounds of nature (birds singing, breeze, water flowing), creating a “sound landscape” (Schafer, 1994, p. 33) and recalling well-known melodies by Sarasate, Vivaldi and Strauss.

In the scene of Hutter’s journey through the forest at dusk on his way to Orlok’s castle, the movement of the carriage has the agitated character of scherzo of Beethoven’s music accompanied in the imagery with an accelerated or undercranking movement (Konigsberg, 2004, p. 72) of the sprung cart. Upon Hutter’s arrival at the castle, the melodic treatment alludes to brushstrokes by Liszt and Chopin; while the orchestration is reminiscent of Mahler’s great symphonies, where the moment of his entry into the vampire’s abode, when Orlok appears in the scene, is sublime.

Erdmann goes further and empowers the instruments by associating them with elements of the props, enriching the film imagery by providing it with descriptive music; thus, the scene in which the clock strikes midnight (acoustic effect) is associated with the triangle.

In his score there is a glimpse of a certain influence of the Wagner leitmotif (Chion, 1997, p. 259), such as the scene in which after midnight Nosferatu enters the bedroom surprising Hutter, and this is done with the xylophone scales.

Romanticism permeates the final scene of the death of the lovers, Ellen (Jonathan’s wife) and Orlok (Nosferatu), both in the imagery (careful artistic and scenic direction in the props, detail of the furniture, costumes) and in the music (clarinet motif repeated in duet on violins) to express the immense sadness that overwhelms that moment of death through love, as a mention to the poetics of romanticism.

The composition draws on musical influences confined to romanticism. Baroque brushstrokes can be identified such as basso continuo on strings, variations, modulations of the main theme and embellishments to intensify emotions (Grout & Palisca, 2002, pp. 490–491) in the inn scene before Hutter started the journey to the castle, with a hint of baroque dance.

There are also allusions to classicism through symmetrical phrasing, balanced phrases delimited by cadences, ideas combining wind and string culminated in orchestral tutti in the boat’s night scene, where the stunned crew discover stinky rats in the count’s coffins.

And traces of impressionism through sound waves of violins, imitating flashes in continuous crescendos and diminuendos which are reminiscent of Debussy and colourful instrumental combinations in the cliff scene while Ellen awaits news of her husband, with the only company of the movement of the waves and the breeze that further emphasise her immense solitude.

Musical Study of the Film

For a detailed analysis, it is limited, for spatiotemporal reasons, to three fragments selected (2008 edition, Divisa Ediciones) for their narrative and aesthetic, and instrumental relevance.

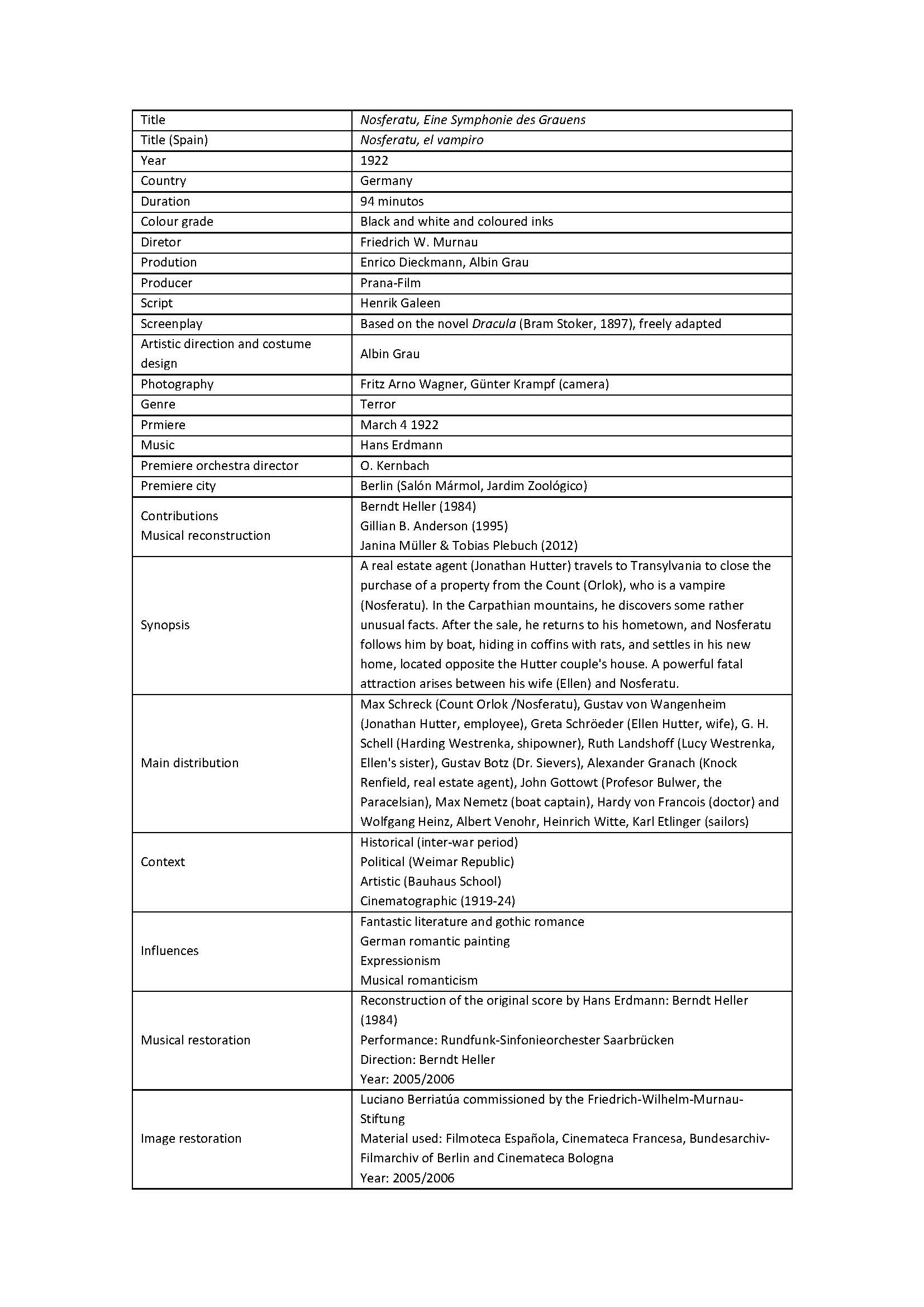

Fragment 1: Hutter’s Journey to Count Orlok’s Castle

A real estate employee (Hutter), staying at an inn, who has travelled to Transylvania for the purchase of a property by a count (Orlok), who is a vampire (Nosferatu). In the land of the Carpathians, strange events take place (00:17:57-00:25:26).

Musically, it has a descriptive tonal melody, with a refined orchestration work of symphonic instrumentation (strings, woodwinds, and brass for two, percussion and piano) , and melodic and thematic development inspired by previous eras (baroque, classicism, etc.). The beginning is reminiscent of an overture in the style of Verdi, dialogued between string and woodwind (oboe, flute, and clarinet solos).

The scene begins with Hutter waking up in the inn bedroom. The rays of dawn enter through the cracks in the window and fill the bedroom with a luminous gold reinforced by sepia tinting of the frame while listening (sound off) to the birds singing. Upon opening the window, you see a large general shot and depth of field of the horses trotting freely through the countryside, while a mountain range can be seen on the horizon (an allusion to the Carpathian Mountains). It is a bucolic, pastoral landscape where the music provides an idyllic atmosphere, accompanying the imagery where the instruments fulfil a “referential function” with the landscape (Jakobson, 1981, pp. 347–395).

Musically it begins with a very high-pitched triangle (struck in a military fashion), to wake Hutter from a deep sleep. The timbre of woodwinds and violins identifies with sounds of nature (birds chirping). A resource that is very present in the history of music: The Song of the Nightingale by Sarasate, The Four Seasons by Vivaldi or An Alpine Symphony by Strauss.

Once again, the penetrating triangle (repeat of the initial theme) breaks in and a ritardando leads to a new clarinet motif (Graph 1, Figure 1), supported by a rhythmic ostinato on snare and tambourine (Graph 2, Figure 1). Coinciding with Hutter’s discovery of a bedside book on vampires, the strings permeate the scene with a halo of mystery. Then, laughing, Hutter throws the book on the floor, while washing himself to the sound of a joyous melody of clarinets that reinforces his actions and mood.

Source. Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Friedrich Murnau, 1922)

Figure 1 Hutter’s journey to count Orlok’s castle

By parallel montage, the coachmen prepare the carriage, while the lyrical and expressive character of the strings gives credence to the imminent journey. Musically, it begins with a scherzo character, lively and agitated tempo, imitating the accelerated movement (undercranking) of the carriage. An ascending progression, in crescendo on the strings, leads us to a new motif. The piano (soloist) produces a theme in ascending arpeggio (octaves), dialoguing with strings and woodwinds, repeating the same phrase in question-answer form (Graph 3, Figure 1), recalling Beethoven’s Eroica.

While the light of dusk is accentuated in the imagery with the frame tinted from shades of pink to ochre, it musically sees a change of motif, as a clarinet call (descending arpeggio) is repeated up to four times (Graph 4, Figure 1). Two musical proclamations are produced in tutti (major and minor mode), providing greater drama. A prolonged ritardando keeps the tension in a semi-cadence. The coachmen have a bad premonition and suddenly stop the carriage while saying to Hutter (script text): “pay what you want. We won’t continue on”. For a second there is a shocking silence, the feeling of emptiness to emphasise the disturbing moment. A cello solo on a string pad envelops the inhospitable atmosphere of the rugged landscape, as a parenthesis in scherzo as, while the incredulous Hutter laughs out loud, the main theme returns with a motor rhythm on strings and a melody on woodwinds (clarinets and flutes). The same ascending string progression is repeated, culminating in timpani with a staccato string ending (stately character).

This soundscape accompanies Hutter through a bleak rocky landscape. He travels alone, walking, and crosses the bridge that leads to Orlok’s castle. It is an image of strong symbolic weight since the bridge separates the world of the living from that of the dead and that threshold is reinforced with silence (acoustic effect) to further highlight the division of both worlds (the real one and the one beyond). Faced with the need to express gloomy moments and sinister landscapes, Erdmann uses repetitions and passages that evolve through joint movement, presenting chromaticism in brass as a novelty.

The imagery is accompanied by brushstrokes of the full romanticism of Liszt and Chopin. With a change of melody, character, and atmosphere, starting in the low register and the timpani (constant motor as a funeral march). The trumpets develop a motif (Graph 5, Figure 1), on a powerful string motor rhythm that approaches the climax, creating a contrast that evokes Mahler, emphasising Hutter’s desolation through the use of mute (harrowing and macabre effect).

After the script text “as soon as Hutter crosses the bridge, he is taken aback by haunting visions”, the darkness of the night permeates the forest with a tinted dark blue frame and the castle’s great tower can be seen imposingly at the top. A new black carriage rapidly approaches (undercranking) down the winding road to meet Hutter, enlivened by waves of the sound of violins imitating flashes and whirls, in continuous crescendos and diminuendos, reminiscent of Debussy. A descending progression in violins increases their sound mass until the low register, accompanying the descent of the carriage towards Hutter, culminating in a note played in brass and a timpani roll, while an enigmatic coachman is shown in the foreground who camouflages his face with a huge hat and the high collar of his cape. An intense poetic silence intensifies the intrigue of the encounter, while he indicates to Hutter, with a hand gesture wielding the whip, to get into the carriage. The string progressions are resumed to the dizzying rhythm of the carriage, and the sound bursts reflect the fantastical and dreamy atmosphere of the impressionist music that envelops the journey. In the thick mist of the night, you can see the black silhouette of the carriage that becomes more visible as it approaches, protected by the musical envelope (the orchestration and sound volume increase).

With his arrival, a succession of accents in tutti begins that pass on to the piano. The coachman wielding the whip orders Hutter to enter the castle, and a very close-up of the tower bursts into the image, accompanied by a string motif in a low register, a mysterious melody, aided by sudden timpani interventions (sinister atmosphere). Hutter watches as the carriage rushes away and the enormous gates of the castle swing open by themselves, with an expressive melody in a tone of resignation. A timpani beat announces his arrival, while the gates magically close. Orlok comes out to greet his guest amidst a gloomy atmosphere with expressionist lighting, shadows highlighted by the dark blue of the frame that accentuates his presence at night, as his body emanates a huge shadow of a ghostly image. When they meet, a call of violins envelops the scene, highlighting the perplexity of the moment, since the enigmatic coachman and the count are the same person.

After a new intertitle “you have made me wait so long. It is almost midnight”. The servants are sleeping while the host gives way to the guest. The climax arrives with a smashing of plates. As they enter the castle, the oboe accompanies with an increasingly distant melody that loses energy, volume, and intensity, to conclude and close the scene in tutti.

The movement of the action runs parallel to the music, generating tension with long phrases. The relationship between the accompaniment and the main theme, as well as the relationships between instrumental families, timbral contrasts and effects are the basis of the orchestration of this fragment that sets a precedent in composition for film (Figure 1).

Fragment 2: Ellen’s Trance

Hutter is staying at Orlok’s (Nosferatu’s) castle, while he carries out real estate management for the purchase of some properties in Wisborg. After midnight, the count (vampire) bursts into Hutter’s bedroom, intending to bite him and suck his blood. But, in the far distance, his wife (Ellen) portends that something terrible is going to happen to her husband and enters a trance, wakes up screaming at midnight and wanders barefoot through the rooms. In an altered state of consciousness, she enters a telepathic connection with the vampire who leaves her husband’s bedroom (00:33:11-00:37:58).

It is a scene of great lyricism, where despite the prevalence of tonalism, the contrast effects reinforce the content. After a passage of notable expressive value on string (F major), as a cry, the first effect appears with a powerful chromaticism, functioning a posteriori as the main element (Graph 6, Figure 2).

In the privacy of his bedroom, Hutter kisses his wife’s portrait on his pocket watch, where candlelight in a sepia ochre colour of the frame warms the moment accompanied by a violin motif, a loving melody while remembering his beloved wife, interrupted by a descending string and xylophone scale (Graph 7, Figure 2). It coincides with the showing of the vampire book that Hutter had found in the inn and takes out of his satchel in surprise. It is a strange occurrence that produces uncertainty and is supported melodically by chromaticism that introduces the theme in the tonic (inconclusive cadence), creating instability and suspense (Graph 8, Figure 2).

A rhythmic base starts in contrabass, with sudden sforzando on string. Hutter sneakily peeks through the book trying to figure out what is happening while reading (script text, diegetic text, gothic calligraphy, tinted blue-green frame) “at night Nosferatu wounds his victim with his claws and sucks his blood, the diabolic vital brew”, turns his head looking towards the door of the room, scared and afraid of being found. He continues reading (script text) “make sure that his shadow does not interfere with you, like a frightening nightmare”.

A refined and balanced melodic line is drawn, creating new instrumental colour effects (chromaticism takes us to the dominant one), seeking its full sound to create specific effects and atmospheres. The descriptive melody associates instruments with decorative elements of the props. Thus, the very high-pitched triangle identifies with the hour mark of the clock. There is elaborate staging of a close-up of a mechanical table clock made of gilt bronze and a round dial with Roman numerals, decorated in the upper part by a figure of a human skeleton that strikes a bell to mark the hours. At midnight exactly 12 counter-beat triangle strokes (one stroke for each chime) and a descending xylophone scale are heard. It is a moment of exquisite film and music plasticity as, together with the expressive force of the melody, an artistic direction of everyday objects with gloomy shapes and expressionist lighting is devised, where the shadow of the macabre clock generates an animated ghostly image.

Hutter creeps towards the door of the room and when he opens it he sees Nosferatu amidst the darkness. He has a hieratic, emaciated body that personifies ugliness, with a huge shadow reflected on the wall that further accentuates the darkness of the room. Musically, the descending xylophone scale is heard, when a frightened Hutter closes the door. A four-note motif is constantly repeated on string until the door magically opens, with Nosferatu approaching with robotic strides, culminating in a dissonant chord (Graph 9, Figure 2).

The vampire approaches the bedroom, passing through the pointed arch of the door, accompanied by a static xylophone and string melody, alternating with flute trills. The xylophone identifies Nosferatu, although he is not visible in the scene, by his inexpressive character (an instrument without resonance) which contributes to describe slow, robotic, dry, incisive, and inhuman movements of the vampire. A sforzando in tutti, accompanied by a timpani roll, reflects Hutter’s fear as he covers his face with the sheets in terror.

When Nosferatu freezes at the entrance to the room, an intense silence envelops the scene. Erdmann insists on its use for rhetorical purposes to emphasise the moment of desolation. A change of location, by parallel montage, takes us from Transylvania to Wisborg, where Ellen is sleeping in her bed at that moment. The piano and the low register of the strings accompany her dream, which, due to its disturbing chords, does not seem pleasant. The darkness of the night, with the tinted dark blue frame, invades the bedroom, as she wakes up, gets up sleepwalking, walks barefoot on her tiptoes, goes out onto the terrace, and begins to walk along the balcony railing. She is beside herself, on the edge of the abyss and passes out. Flute and xylophone melodies alert Hutter’s friend that something bad is happening. The instruments function as a leitmotif. The xylophone (representing Nosferatu) present in the action through music is heard in the background while Ellen is the flute (innocent and warm timbre).

The imagery takes us to Transylvania, to Hutter’s bedroom. The dissonance in piccolos tense the atmosphere and accompany the enormous shadow of Nosferatu, who comes to life and slowly pounces on Hutter, curled up in the corner of the bed, giving a ghastly dimension to the scene. The xylophone is reinforced with the combination of chromatic elements and muted trumpets. The melodic discourse is directed towards the climaxes, highlighting flute motifs on a melodic pad in low strings, creating a motor that generates tension as a double image of the shadows.

At the same time Ellen, waking up from a horrible nightmare, rises from the bed spreading her arms and shouting her husband’s name. A clarinet motif (an instrument that identifies Hutter) accompanies her call for help. The shadow of Nosferatu, alerted by Ellen’s desperate cry, vanishes, with the sound density decreasing. The vampire turns and directs his gaze (off field) towards Ellen, highlighting the existence of a bond between them. Nosferatu leaves the room slowly, accompanied by the xylophone, with the door magically closing behind him. At that moment, in the distance Ellen falls onto the bed exhausted, and an oboe and clarinet melody slowly fades until she rests (Figure 2).

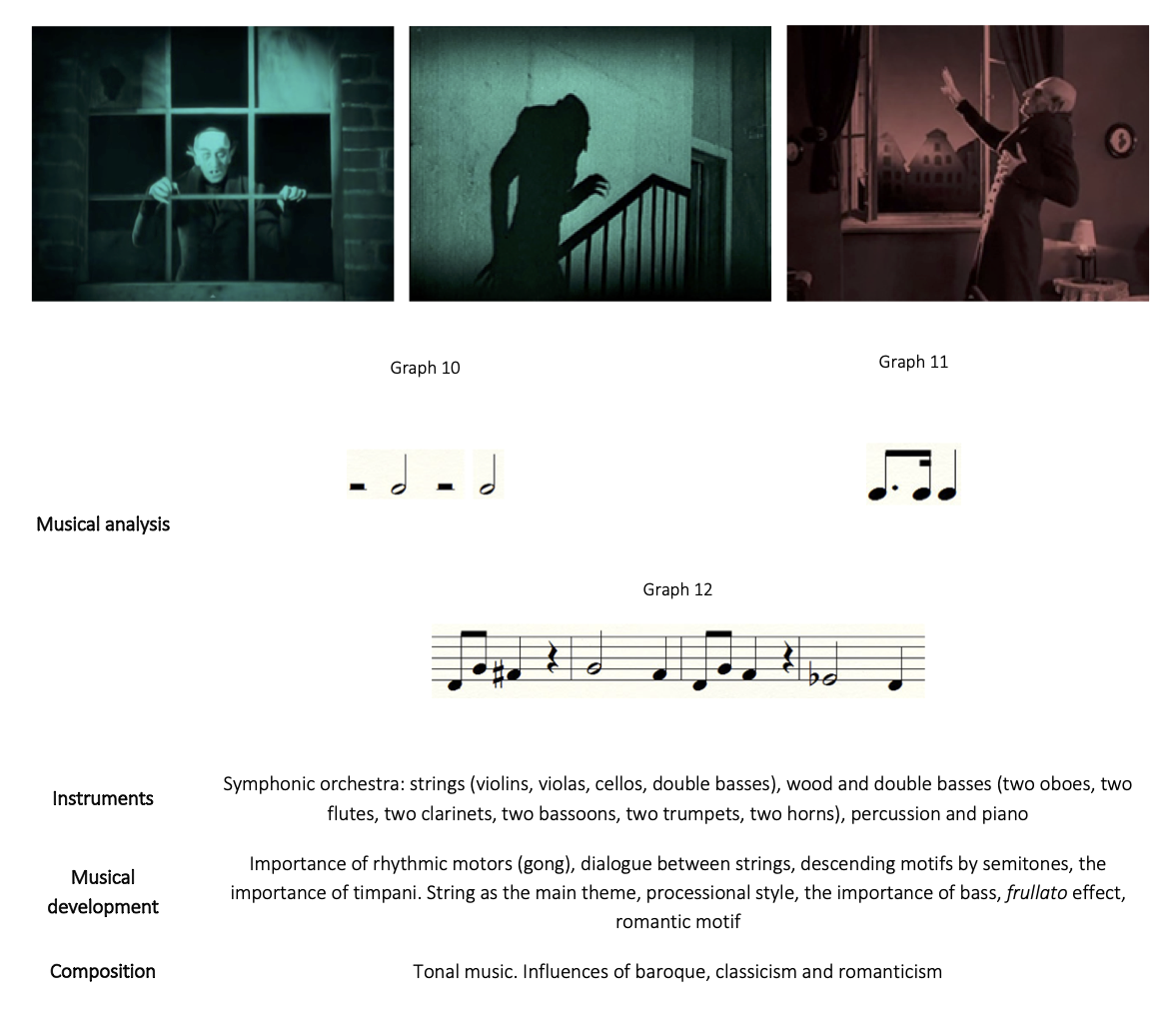

Fragment 3: Death of Nosferatu and Ellen

Orlok has settled into his new mansion opposite the Hutter’s marital home. Ellen succumbs to Nosferatu’s fatal attraction. At dawn, the vampire enters her bedroom while her husband goes in search of the doctor (Bulwer). Nosferatu and Ellen desirously lie on the bed. Daybreak surprises them, as the first rays of dawn invade the room and end the vampire’s life, while Ellen is reduced to the same fate (01:25:37-01:33:20).

It is a sentimental scene in the pure Romanticism style, which is musically descriptive, with constant motor rhythms. The use of the gong stands out to highlight moments charged with drama, whose purpose is to attract attention (Jakobson’s “factual function”). It is used as an effect associated with movement, which culminates in the string calls, creating a strong contrast with the nocturnal atmosphere accentuated in the imagery with the tinted dark blue frame (Graph 10, Figure 3).

Source. Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Friedrich Murnau, 1922)

Figure 3 Death of Nosferatu and Ellen

At night, Nosferatu waits motionless, resting his hands on the bars of the dilapidated window of his new abode. It is a symbolic image of the prisoner deprived of freedom and the expectant vampire waiting for his new prey. Musically, the atrocity materialises in the low strings (octaves). With the second strike of the gong Ellen wakes up startled. Two physical spaces alternate by parallel montage, which are the Hutter’s bedroom and the large window of Orlok’s mansion, where a third space is implicitly created, the psychological one, since the vampire and Ellen communicate telepathically.

The low register and the sforzando show Nosferatu’s lack of vigour, highlighting the slowness with which he walks. While Hutter, asleep in the armchair next to the bed, watches over his wife, who is dejected, resigned and powerless in the face of the situation. Ellen cannot resist the attraction of the vampire and, distressed looking at her husband, opens wide her bedroom’s window uncovering her heart. Nosferatu goes towards her, at which time the door of the mansion suddenly and magically opens and he leaves the house, a moment reinforced by a note played on contrabass (increase in sound tension). The sound of the gong, as a call to a ritual, accompanies him to the house of a tormented Ellen, whose thoughts mortify her, enlivened by overwhelming music, dialogued strings, and a descending three-note motif, supported by a timpani roll in crescendo that culminates with the gong.

Her husband wakes up, he is scared to see her in that state of unease, he lies her down in bed and she begs him to call Bulwer. Hutter runs off (descending string motif), but Ellen gets up, tricking her husband into leaving the house. The theme is introduced with a call of timpani, repeated throughout the section (three notes that descend in semitones, add tension, and increase the sound density).

Nosferatu is present through his immense black shadow reflected on the wall, fused with the shadow of the staircase bars, a metaphorical image of the prisoner of love. He enters Ellen’s bedroom accompanied by the expressive force of the music, the tension grows, with the register, sound density and orchestration expanding, and the brass joining in fortissimo, creating a contrast of colours with the instrumentation used. Ellen can no longer bear the anguish and falls onto the bed exhausted (sforzando in fortissimo of the orchestral tutti). She knows her end is near. A forte piano on the timpani accompanies the shadow play of the vampire’s hands on Ellen's white nightgown. It is staging that is reminiscent of shadow puppet theatre, since the shadow of the vampire’s moving hands projects onto the woman’s chest animated figures of flying animals that hold her heart tightly, culminating the state of anxiety with a gong strike.

Hutter wakes up Bulwer (same mysterious string motif). In the parallel montage, Nosferatu lays on Ellen’s body stretched out on the bed. The appearance of the different characters musically shows elements of surprise, and a mixture of simplicity and complexity. Timbral contrasts blend with distinctive rhythmic patterns and sharp, overlapping melodies. Erdmann, in an extraordinary attempt to support the ending, employs a processional-style rhythmic element, defining the funereal character in the low brass (Graph 11, Figure 3).

The first rays of dawn appear on the horizon, subtly permeating the bedroom (section highlighted by the change in the colour tint of the frame from dark blue to sepia). The cock’s crowing announces dawn twice, parodying its sound with different instruments (frullato on clarinet) and alerts not only Nosferatu, but Knock (his faithful servant and estate agent) too. This alert brings him back to reality. He spent the night with his beloved, but daylight comes and he will die with the first rays of the sun. He rises slowly from Ellen’s bed, and walks in a stately manner, with his left hand on his chest resting on his heart in an attempt to preserve his love forever. He turns his face towards the window and while looking (field out) at the morning twilight, his body dissipates.

The sacrifice for love, fear and resignation of the moment are reflected with long phrases, motifs and rhythmic cells that move through different instruments, showing the desperation of the characters. Thematically, clear ideas and defined tonal structures are developed that lead to different sections, accentuating the anguish (inconclusive cadences), producing a sensation of instability and an endless whirlpool.

The final theme outlines an intense and passionate melody that is typical of Romanticism, while Knock shouts (script text) “master! Master!”. The sweet song of the flute represents the sunrise, gives the scene a bucolic air and the mysterious chromaticism accompanies the dawn. The first rays of the sun flood Nosferatu’s body, like luminous splinters that end his life, while a descending scale announces his descent into hell. To the melancholic string melody, lament like a sigh, a sad motif is played on cellos, with a response from violins and violas that reaffirm his tragic death (script text) “the master is dead”(Graph 12, Figure 3).

After a fade to black, the scene returns to Ellen’s bedroom who, in her dying breath, wakes up looking for her husband. Her delusional state is accompanied by a melancholic clarinet melody which is symbolic of her love when Hutter takes her in his arms and she passes away. Feelings of profound sadness and immense love merge into an intense melodic motif, repeating in duet on violins (a romantic instrument par excellence).

The orchestration draws the colourful play of light and shadows present, exploring the instrumental limits in the low extremes (darker timbres and less intense sound) and high-pitched extremes (squeaky and sharp), looking for new effects (instrumental colour and atmosphere). The scene closes by breaking with the lived drama, reaching a tonal cadence that releases all the accumulated tension, while the prophecy is shown in the image (script text, diegetic text, gothic calligraphy and tinted blue-green frame) “and according to the truth, the miracle is documented: the great death ceased at the same time and, as before, the victorious rays of the sun, full of life, dispelled the shadows of the prophet of doom”. It closes with a general shot of count Orlok’s castle in Transylvania, and with a fade to black the film ends (Figure 3).

Final Remarks

Murnau’s Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens is considered a masterpiece of the horror (vampire) genre of German expressionist cinema. There have been significant contributions towards it from different disciplinary approaches, but when it is approached from musicology the studies are scant, a circumstance that may be due to the loss of the original score by Hans Erdmann. Over time, the imagery has been restored on several occasions with different colour tints (Patalas, Berriatúa, etc.) and the same has happened with the score (Heller, Anderson and Kessler, Müller and Plebuch). The film restored by the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung Foundation (2005/06) has an original score reconstructed by Heller (1984).

The film draws on cultural references of the era, romantic and expressionist painting, fantasy literature and gothic novels, kammerspiel and romantic music. It is a composition that shows the evolution of musical romanticism and its reference to pieces by renowned composers. Erdmann opts for a large-format, programme symphony, created around a descriptive theme, reaching out to other musical styles.

The score is structured into five acts that correspond to the parts of the story of Nosferatu, imitating the symphony form with different movements. It is an intense romantic creation, with tonal music and a certain influence from baroque, classicism and impressionism that plays with the emotional state creating atmospheres, adapting to each of the scenes and respecting the smallest detail thanks to the mastery of chromaticism and dissonance.

Erdmann opts for symphonic instrumentation that ennobles the film text by associating characters with instruments, their actions and emotions with melodies and scenes with a certain music. He feels influenced by the Wagner leitmotif which gives the film sound density, and he majestically uses musical silences with poetic purposes. He masterfully develops musical forms such as the fanfare and the funeral march, without losing originality, combining all kinds of techniques, orchestration, and styles. He skilfully uses the dialogues between different instrumental families and gives a relevant role to the percussion and its multiple effects.

In the melodic treatment he is influenced by Liszt and Chopin; at the orchestration level he relives the great symphonies of Mahler; he masters the dramatic impact and rich orchestration of Stravinsky; he memorably references Beethoven’s scherzos; he leaves traces of Debussy’s compositions, with sound waves of violins, imitating flashes in continuous crescendos and diminuendos; he tactfully connects the technique of the Wagner leitmotif, guiding the melody in different directions and creating unique and unrepeatable melodic moments; he relives Verdi-style martial accompaniments; and subtly evokes melodies from Vivaldi and Strauss.

The instrumental ensemble presents the different characters that make up the story’s love triangle, the actions they perform, feelings that torment them and unspeakable desires they feel; thus, Nosferatu is represented by the xylophone, Ellen by the flute and Jonathan by the clarinet. Certain instruments are also used to describe emotions that emerge from the different landscapes of the film’s story: the striking sound of the gong, in a solemn call to the love affair of Ellen and Nosferatu; the frullato on the clarinet, imitating the cock’s crowing at dawn; the high-pitched sound of the triangle as a bugle call to wake up Hutter; or the violins, alluding to the birds chirping. Hans Erdmann’s music is harmoniously integrated with Friedrich Murnau’s imagery, and it is a soundtrack in perfect symbiosis with the film’s story.

REFERENCES

Adorno, T. W. (2008). Ensayo sobre Wagner. Akal. [ Links ]

Altman, R. (2007). Silent film sound. Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Amorós, A., & Gómez, N. (2017). La música de Rainer Viertlböck en la versión restaurada del film Daskabinett des Doktor Caligari, de Robert Wiene (1919). Cuadernos de Música, Artes Visuales y Artes Escénicas, 12(2), 321-343. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.mavae12-2.mrvv [ Links ]

Amorós, A., & Gómez, N. (2018). The German expressionist film The Golem (1920): Study of the music soundtrack by Aljoscha Zimmermann. L’Atalante. Revista de Estudios Cinematográficos, 26, 181-198. [ Links ]

Anderson, G. B. (1988). Music for silent films, 1894-1929: A guide. Library of Congress. [ Links ]

Ashworth, P. D. (2000). Qualitative research methods. Estudio Pedagógico, 26, 91-106.http://revistas.uach.cl/pdf/estped/n26/art07.pdf [ Links ]

Berriatúa, L. (1990a). Apuntes sobre las técnicas de dirección cinematográfica de F. W. Murnau. Filmoteca Regional de Murcia. [ Links ]

Berriatúa, L. (1990b). Los proverbios chinos de F. W. Murnau (Vol. II). Filmoteca Española. [ Links ]

Berriatúa, L. (2001). Conocer los materiales para restaurar películas. Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes Instituto de la Cinematografía y Artes Audiovisuales Filmoteca Española. [ Links ]

Berriatúa, L. (2009). Nosferatu: Un film erótico-ocultista-espiritista-metafísico. Divisa Red. [ Links ]

Berriatúa, L., & Pérez, M. Á. (1981). Etudes pour une reconstitution du Nosferatu de F. W. Murnau. Les Cahiers de la Cinémathèque, (32), 61-74. [ Links ]

Bouvier, M., & Leutrat, J.-L. (1981). Nosferatu. Cahiers du Cinéma Gallimard. [ Links ]

Casetti, F., & Di Chio, F. (2007). Cómo analizar un film. Paidós. [ Links ]

Chion, M. (1982). Leson au cinema. Cahiers du Cinéma. [ Links ]

Chion, M. (1993). La audiovisión: Introducción a un análisis conjunto de la imagen y el sonido (A. L. Ruiz, Trad.). Paidós. (Trabalho original publicado em 1990) [ Links ]

Chion, M. (1997). La música en el cine (M. Frau, Trad.). Paidós. (Trabalho original publicado em 1995) [ Links ]

Colón, C., Infante, F., & Lombardo, M. (1997). Historia y teoría de la música en el cine: Presencias afectivas. Alfar. [ Links ]

Deutsche Kinemathek. (2003). Retrospektive, filmografie.https://www.deutsche-kinemathek.de/retrospektive/retrospektive-2003/filme/15 [ Links ]

Eisner, L. H. (1964). F. W. Murnau. Le Terrain Vague. [ Links ]

Eisner, L. H (1996). La pantalla de moniaca. Las influencias de Max Reinhardt y del expresionismo (I. Bonet, Trad.). Cátedra. (Trabalho original publicado em 1955) [ Links ]

Fraile, T. (2007). El elemento musical en el cine: Un modelo de análisis. In J. Marzal & F. J. Gómez (Eds.), Metodologías de análisis del film (pp. 527-538). Edipo. [ Links ]

García Merino, J. (2016). Nosferatu y la consolidaciónde la música de cine. In Programa Nosferatu, eine symphonie des grauens (pp. 3-11). Junta de Castilla y León. Consejería de Cultura y Turismo Fundación Siglo para el Turismo y las Artes de Castilla y León.https://www.oscyl.com/assets/oscyl-programa-nosferatu.pdf [ Links ]

Gillian Anderson. (s.d.). Nosferatu.http://www.gilliananderson.it/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&layout=item&id=22&Itemid=29 [ Links ]

González, J. L. (2008). Vampiros en el cine mudo. ‘Nosferatu’ (1922) de Murnau. Revista Cine y Letras.http://www.cineyletras.es/Clasicos-y-DVD/vampiros-en-el-cine-mudo-nosferatu-1922-de-murnau.html [ Links ]

González Hevia, L. (2012). La sombra del vampiro. Su presencia en el 7º arte. Cultiva Libros. [ Links ]

Grout, D. J., & Palisca, C. V. (2002). Historia de la música occidental. Alianza Música. [ Links ]

Hayward, P. (2009). Terror tracks: Music, sound and horror cinema (genre, music & sound). Equinox Publishing. [ Links ]

Heller, B. (1984). Restauración. In Nosferatu. La película. Divisa Home Video. [ Links ]

Jakobson, R. (1981). Ensayos de lingüística general. Seix Barral. [ Links ]

Jameux, C. (1965). Murnau. Editions Universitaires. [ Links ]

Konigsberg, I. (2004). Diccionario técnico akal de cine. Akal. [ Links ]

Kracauer, S. (1985). De Caligari a Hitler. Una historia psicológica del cine alemán (H. Grossi, Trad.). Paidós. (Trabalho original publicado em 1947) [ Links ]

Lack, R. (1999). La música en el cine (H. Bevia & A. Resines, Trads.). Cátedra. [ Links ]

Lerner, N. (2009). Music in the horror film: Listening to fear. Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Lluis i Falcó, J. (1995). Paràmetres per a una anàlisi de la banda sonora musical cinematográfica. D’Art. Revista del Departament d’Història de l’Art, (21), 169-186. [ Links ]

Marks, M. M. (1997), Music and the silent film: Contexts and case studies, 1895-1924. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Müller, J., & Plebuch, T. (2013). Toward a prehistory of film music: Hans Erdmann's score for Nosferatu and the idea of modular form. Journal of Film Music, 6(1), 31-48. https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.v6i1.31 [ Links ]

Murnau, F. G. (Diretor). (1922). Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Filme). Prana-Film. [ Links ]

Navarro Arriola, H. y S. (2005). Música de cine: Historia y coleccionismo de bandas sonoras. Ediciones Internacionales Universitarias. [ Links ]

Neumeyer, D., & Buhler, J. (2001). Analytical and interpretive approaches to film music (I): Analysing the music. In K. Donnelly (Ed.), Film music. Critical approaches (pp. 16-38). Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Nieto, J. (2003). Música para la imagen: La influencia secreta. SGAE. [ Links ]

Olarte, M. (2004). La música de cine. De los temas expresivos del cine mudo al sinfonismo americano. En J. M. García (Ed.), La música moderna y contemporánea a través de los escritos de sus protagonistas (pp. 109-126). Doble J. http://hdl.handle.net/10366/76672 [ Links ]

Olarte, M. (2008). Utilización de la música clásica como música preexistente cinematográfica. In J. M. García & E. Arteaga (Eds.), En torno a Mozart. Reflexiones desde la universidad (pp. 71-84). Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. http://hdl.handle.net/10366/76649 [ Links ]

Patalas, E. (2002). Les restaurations du ‘Nosferatu’ de Murnau. Cinématèque, 21, 117-134. [ Links ]

Peña Sevilla J. De la (2000). Una aproximación iconográfica del cine de vampiros. Imafronte, (15), 237-254. [ Links ]

Riemann, H. (1928). Teoría general de la música. Labor. [ Links ]

Román, A. (2017). Análisis musivisual. Guía deaudición y estudio de la música cinematográfica. Visión Libros. [ Links ]

Rubio, S. (2005). Nosferatu y Murnau: Las influencias pictóricas. Anales de Historia del Arte, 15, 297-325. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Biosca, V. (1985). Del otro lado: La metáfora. Modelos de representación en el cine de Weimar. Instituto de Cine y Radiotelevisión/Hiperión. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Biosca, V. (1990). Sombras de Weimar, contribución a la historia del cine alemán 1918-1933. Verdoux. [ Links ]

Schafer, M. (1994). The soundscape: Our sonic environment and the tuning of the world. Destinity Books. [ Links ]

Stake, R. E. (2007). Investigación con estudio de casos. Morata. [ Links ]

Tagg, P. (2012). Music’s meanings. A modern musicology for non-musos. The Mass Media Music Scholars Press [ Links ]

Tieber, C., & Windisch, A. (2014). The sounds of silent films: New perspectives on history, theory, and practice. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Tone, P. G. (1976). Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. La Nuova Italia. [ Links ]

Torelló, J. (2015). La música en las maneras de representación cinematográfica. Laboratori de Mitjans Interactius. [ Links ]

Valls, M., & Padrol, J. (1986). Música y cine. Salvat. [ Links ]

Notes

Received: October 25, 2021; Revised: November 29, 2021; Accepted: November 29, 2021

texto em

texto em