Introduction

Printed publications are elements of visual culture, and their relation to historical and contemporary narratives and their aesthetic value is socially built. Print media and its production, editing, circulation, and research result from publishers' choices and are related to their social, cultural, and historical context. This article aims to deepen the discussion about the importance of publishing with "corpa"1. "Corpo" is a masculine noun in Portuguese, so "corpa" is the feminization of this word to reverse the practice of perceiving the masculine body as the default human experience and central to intellectual production. The term refers to all dissenting bodies — not just the feminine — that do not fit White capitalist patriarchy (b. hooks, 2015). Referring to dissenting bodies as "corpa" is to highlight the physical, or visceral, the scope of the abstract concept of intersectionality. Here, the physicality of the dissenting body torn by the political paradigm denounced by intersectional thought is approached by the artistic subversion of visual culture through the physical form of the printed page.

The Jornal de Borda claims a very interesting history of Latin American publications. It ran for 6 years, had 10 editions, was released in Brazil, Uruguay, Mexico, and Argentina, and was further distributed in Portugal, Chile, and Peru. Issues 1 and 2 were published in 2015, Issue 3 in 2016, 4 in 2017, 5 in 2018, 6 and 8 in 2019, and 10 in 2021. They all had 5,000 copies distributed across Latin America. In Issue 7, from 2019, there were 200 copies, and in Issue 9, from 2021, 100. Throughout these years, nearly 200 people contributed from several places in the Americas. A Plebe, an anarchist newspaper founded in 1917, ran at 10,000 copies per issue and was a major inspiration for the creators of Jornal de Borda. Alongside the artistic expressions of the participants, there was also a desire to pay homage to the legacy of international anarchist movements through printing — to keep the tradition alive in the face of lingering political crises.

By discussing the Jornal de Borda, more specifically its latest edition O Borda, innovative publication tools and aesthetics are revealed beyond those named by art history and its market and as anarchist contributions to the visual culture of publishing. The proposal of its visual study within and from the global south (Lozano de la Pola, 2019) faces a double challenge: unveiling, or making visible, the place of enunciation of the hegemonic gaze and understanding its mechanisms of production of epistemic racism through visuality and its universalist claims while presenting the production of those "othered".

For those who work with printed material in countries like Brazil, telling the story of Latin American publications from a decolonial perspective is necessary because the colonial reality is inescapable in every realm of our existence throughout history. As a capitalist way of managing taste, what you should see, read, and have in your space, the market is an extension of the Latinx relationship with colonialism — an imposition of western values and visualities. Art and publications need a subversive character to escape the commodification of taste. Telling this story beyond visual arts, beyond the market, and from an anarchist perspective contributes to the social criticism of publications as expressive political tools in the face of neocolonialism and its capitalist facet.

Artists' Publications From Above and Below

Books and publications are essential for artists. With the advent of the artist's book and the exhibition catalog, the printed page has become a timeless exhibition space valued by the art market and those who research and curate art. The history of art publications and printed exhibitions in Brazil fits into a history that has American and European art as landmarks (Silveira, 2001). That is why Ed Ruscha is relevant to this conversation — the tools that justify him being an iconic artist's book maker were used by anarchists, and modernists in Brazil and Latin America, in the early 1900s. His printed work's subversive and provocative nature, its pushing of artistic limits, and the status quo can only arbitrarily be described as groundbreaking.

To test the limits of what defines art is not only an artistic process but a political one. The academic concept of an artist's book can and must be extended to remain consistent with an artist's vision. Moreover, if the process of academic categorization does not accommodate the realm of political publication, it erases a universe of artistry that suffered from political censorship and engaged politically during major historical events. After all, visual culture is the collective expression of a people and seeks to impose no boundaries on what constitutes visual expression (Grigolin, 2015). In this fashion, a book is a publication, and so is any other printed page made public. Other publication formats such as newspapers and pamphlets — or any tool used to make printed pages public — are relevant to the conversation about artists' books.

The main publication tools that define an artist's book are: it is made by an artist; it is an art form; and it does not depend on an institutional space to be displayed (it can be on a wall, in a bag, or a library; Brogowski, 2011). There is an argument to be made of what an artist's book is not and that the 21st century's book industry's requirement of barcodes and the possibility of print on demand are the tools of an artist's book antithesis (although both can, in turn, be appropriated as artistic tools). As an art form, the book object can be both a unique and a mass-produced piece because its mass-produced quality may, paradoxically, enhance its unique features. In art, we have seen this paradox in Andy Warhol or Banksy's coveted pieces. In the publication, we can see this in the example of Fabiana Faleiros' art book, whose large but limited edition is printed with a plain white cover. The artist handwrites "MasturBar" on the cover of each copy as a signature, autograph, and title (Faleiros, 2016).

The circulation strategy also makes a book an artist's book. It may be in a bookstore or library, and it may question the format of a book by bringing other forms of print into circulation. For instance, it may have an envelope as a cover, or it can be made small like a zine (Grigolin, 2020), or dialogue with other publication formats like a newspaper (Jornal de Borda). Therefore, the term artist publication is suitable as it includes the book and other printed formats.

Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations, by the United States American artist Edward Ruscha, is considered a landmark in this way of producing art; it is a book from 1963 that explores the graphic design, editing, typography, and other elements of the artist's choices. According to the art historian Mark Rawlinson (2013), Ruscha's work questions a particular set of problems related to art conception, production, and distribution. The problem is the possibility of having an idea, embarking on a journey to execute this idea, then having this idea documented, published, and sent off into its own journey through places and time — only to perhaps have it be perceived as stupid wherever it goes. Why do it? Why do art and immortalize that art in the form of a book?

Therefore, art historians tend to consider the artist's book as the moment when the production, editing, and circulation of an artistic project becomes part of the art itself as a political and aesthetic/conceptual strategy. Among the various possibilities of the artist's book, Drucker (2004) highlights its potential to address various individual experiences and, therefore, express various activist approaches toward combatting oppression and injustice. In this sense, art is a political strategy and vice versa.

Art in book form has a public vocation. Vocation is derived from the Latin verb vocare, which means "to call". The "call" of the book is public. Brogowski (2011) points out the subversive role of the book: it symbolizes the artistic revocation of the work of art as an object-fetish, causing a crisis in the institutional system. Certainly, the subversion included in books is linked to their public character, and the politically subversive nature of artists' books existed before the artist's book became a category in art institutions.

In Brazil and Latin America, the history of publications (Silveira, 2001) is related to collective initiatives of literary and artistic movements rather than subscribing to the vision of a solitary genius artist who produces printed work. Brazilian magazines such as Revista de Antropofagia from the 1920s and Homem do Povo from the 1930s were created by modernists to be a literary product that intersected with other arts (and can be seen as intermedia). Brazilian modernism can be seen as an aesthetic project that produced knowledge and established relations with ways of living and being in the world that went beyond the realm of art and the individual who produced it.

Other examples of intermedia artist publications from Latin America include the magazines Klaxon from Brazil, Avance from Cuba, and Horizonte from Mexico. The poet Guilherme de Almeida designed the cover for Klaxon, published from May 1922 to January 1923. In Cuba, the Revista de Avance featured amazing experimental works from the island in the 1920s, such as those by prize-winning poet Regino Pedroso. The magazine Horizonte, published between 1926 and 1927 in Mexico, addressed social and political concerns. It was linked to the interdisciplinary stridentist movement, a group that counted on the membership of Tina Modotti, a revolutionary Italian photographer who contributed greatly to the "Mexican Renaissance" (M. Hooks, 2017). All these publications predate Rusha's work and use similar artistic tools, except in their characteristic of collectiveness.

Another pertinent observation when looking at Latin American and Brazilian publications is that, in the 1960s, the history of the artist's book is inseparable from the contestation and practice of fighting against the Brazilian dictatorship (Freire, 2009). In the 1960s and 70s, artists collectively produced magazines of an artisan nature and often circulated them by mail through a marginalized network in South America, as was the case of the Vigo Diagonal Cero magazine edition, a journal founded in La Plata, Argentina.

Magazines have been important for Brazilian art history to document and disseminate subversive political ideas, bypassing dictatorial censorship with visual and artistic tools (Freire, 2009). The Revista Arteria, a magazine by Omar Khouri and Paulo Miranda which is still being published in Brazil, was launched in 1975. In its 4 decades, it has documented art and poetry movements blooming from a barren landscape suffering from severe censorship and repression well into a new millennium with new technological tools and expressions.

The same year Arteria was launched, amid political turmoil in Latin America leading many into exile, the Mexican conceptual artist Ulises Carrión opened the Other Books and So bookstore in Amsterdam, an alternative space, a mix of bookshop specialized in artist's books and political works. Works from Latin American countries were brought together for the first time, leading to more meetings and collaborations. Publications by Argentineans (Leon Ferrari and Leandro Katz), Brazilians (Regina Silveira, Vera Chaves Barcellos, Julio Plaza, Paulo Bruscky, Haroldo and Augusto de Campos) and Mexicans (Magali Lara, Mónica Mayer and Araceli Zúñiga) were all part of Carrión’s initiative.

Creating bookstores and spaces where magazines and books are put together creates an environment for the circulation of ideas. When those are not possible due to political instability and repression, independent distribution, networking, and continent-wide support for a cause are valuable tools. These are public strategies, as well as art forms, performed collectively and in print.

Visual Culture and Independent Publications

To respect the linear Eurocentric approach to history and link visual culture only to art history is like traveling and always returning to the same point of reference, perhaps like Ruscha's gas stations. According to certain visual culture studies (Azoulay, 2015), the image is the source of special knowledge, and its discussion does not end with the image, nor is it circumscribed by the image. Instead, the image is the starting point of a journey, which route — of statements branching from the image — is never known in advance or predetermined.

Since the 1980s, and more specifically from the 2000s, visual studies, anchored in transdisciplinarity, challenged the paradigm of art and its exclusive places for visual reading (Mirzoeff, 1999). Much more than looking at books or publications as objects, it is necessary to look at them as a process and purpose. Visual studies are a tool for analyzing publications because they are verbal-tactile-visual and because they are elements that go far beyond the framework of art history.

The expansion of visual culture studies coincided with the emergence/wider circulation of fanzines, which were linked to punk and do-it-yourself (DIY) culture. Punk, from its inception, was at the intersection of music, aesthetics, and politics — opposed to the establishment which permeated significant realms of the human experience. This opposition, or dissent, was relatable to Latin American corpas and sprouted from the intersectional experiences of marginalized bodies in the United States and Europe. Race and class were at the root of punk rock, moved by an angered White working class in direct contact with Black people and Black culture in the United States and the United Kingdom (Ensminger, 2010).

As a facet of the punk movement, DIY culture specifically addressed the issue of massive mainstream consumption and how it led to a pervasive form of homogenization of human expression, which included art. To disrupt the homogenization of human expression is an expression of dissent, expressed in the physicality of the punk subculture — a corpa.

Industrialized mass production is a tool for the maximum profit within an expanding capitalist system; therefore, its antithesis would be the self-production of goods. DIY is an art form and a political statement because, in late capitalism, it is impossible to live 100% outside this current industrial system. Therefore, the conversation about this system happens as an abstract representation, provocation, and praxis. Hence, the DIY zine is the antithesis of the mass-produced bestseller book. DIY zines are not utopic objects made 100% by hand. These publications can be created at home, without industrial-grade machinery. Thus they do not set out to be identical, profitable, or printed and distributed on a corporate scale. In other words, they are not books you think will sell. They are the book you want to read.

With publication practices in independent spaces and bookstores, such as Banca Tijuana (in São Paulo since 2007) and Printed Matter (in New York since 1976), this culture was later read as a process culminating in what is currently called "independent publication". The adjective "independent" no longer assigns an anti-capitalist characteristic to these publications. It establishes a nomenclature, which is still plural and encompasses handcrafted initiatives and those who want to enter or create a market. Nevertheless, the independent publication can be an art form that traverses and transcends the disciplines of art, history, and politics.

Books and publications may depend on capitalist production, but creating them step by step (Benjamin, 2005) can help us demystify the process of production in order to make it more comprehensive and accessible to the most varied corpas. The division of labor was discussed in print throughout much of the 19th century and is still a relevant discussion today. In the book What Is Art, Tolstoy (1897) claims that

the laborers produce food for themselves and also food that the cultured class accepts and consumes, but the artists seem too often to produce their spiritual food for the cultured only — at any rate that a singularly small share seems to reach the country laborers who work to supply the bodily food! (para. 8)

This anti-capitalist approach towards art and publishing by eliminating boundaries between classes and their labor is further highlighted by Lucy Parsons, who invites her readers to make of the paper what they choose (Parsons, 1905a). That freedom will only come to be when "labor is no longer for sale" (Parsons, 1905b, para. 3). By removing the distinction between producing and authoring, we remove (to the best of our abilities) the capitalist division of labor. Therefore, the artistic anarchist publication is a legacy, a valuable resource passed on through generations, for approaching persistent global socioeconomic issues.

Following each step in creating a book can also help us think about the book in a handcrafted way and from situated knowledge (Haraway, 1988). Situated knowledge is particularly important to consider in a publication because it demonstrates the political responsibility of the content in avoiding the perpetuation of hegemonic views. In acknowledging the author's perceptions as permeated by their individual geographical and historical contexts, the reader is appreciated as having their own perspective. In Brazil, we have a similar political concept called "lugar de fala", the place of discourse. It means knowing the relationship between what you say/the views you hold, and who you are/how your body exists in this world — specifically when it relates to gender, sexuality, and race.

Independent books and publications exist when someone, a corpa, envisions and builds them thinking of broad circulation with publishers, transnationally and personally. Independent publishing goes beyond the capitalist system favoring intimate exchanges over the logic of corporate bookstores. A completely independent book publication, or a completely independent publishing company, does not exist in a capitalist system. Being 100% outside this current system is impossible, so the adjective "independent" cannot be seen in absolute terms.

To think independently about a book or publication as an educational tool in content, format, and editorial experience allows for building a network of Latin American affections. In Latin America, the theory of affection is a doctrine that establishes family ties beyond the realm of biology. This doctrine is extended in the realm of political activism to mean comradery among queer folks who may be rejected by their biological families and face brutal hostility in society2.

For independent publishers and artists, these affection networks are a place of support and protection in cases of severe political repression. They are not exclusive to people who have the same activity niche, circle of friends, or identity. By decentralizing the production chain, mixing the fields of activity and their niches, and building unyielding, transdisciplinary, printed knowledge, it is possible to bring political potential to life.

Jornal de Borda and Anarchism

The political and subversive relationships of publications are seldom addressed in academic discourse about the artist's book, even less so in the art and editorial markets. Brazil, a country where typography was introduced in 1808 with the Portuguese royal family's arrival and the creation of the royal press, can give us captivating answers about how publications — newspapers and booklets — established production, editing, and circulation ties even before the existence of a publishing market. That is so because looking at publications before the existence of the publishing market, implemented in Brazil in 1922, is to understand the beginning of printed production in Brazil.

Our printing and our primary printing place — typography — were developed late compared to other countries in the Americas, but they endure despite the challenges posed by the culture of marketing and publicity. Mass-produced publications using movable types were the first mechanical procedure of wide-range teaching, indoctrination, and reading. In Brazil, this type of typography was established 300 years after it was established in Mexico, and its consolidation process took even longer. At the public level, the relationship with publications developed from the end of the Brazilian empire to the beginning of the republic.

In this transition period from empire to republic, in the 1880s and 90s, the creation of publications had significant links to the anarchist movement. Anarchism was a particularly prominent movement in society, and the discomfort with the arbitrary nature of monarchic power had culminated in public discourse. Therefore, this critical ideology was also prominent in creating and constructing publications. In the city of São Paulo, the first anarchist newspapers in Brazil had a similar reach to that of major non-political forms of contemporary printed expressions. In addition to strengthening social networks, the characteristics of anarchism itself, such as mutual aid and solidarity, permeated the editorial practice in the public space through widespread reading.

According to Vera Chalmers (2018), anarchist editorial production has had transnationality as constant practice and a discontinuous and decentralized editing flow. Unlike newspapers which are sedimented in one city or region of a country, often even bearing the name of its location in its title (e.g., The New York Times, The Washington Post), anarchist newspapers have editors who can start the production of a newspaper in one country, interrupt it and continue in another location. Several social factors and militant practices can lead a publication to move, such as lack of funds and political police action (Chalmers, 2018). Nevertheless, they are not bound by state borders and exist where people envision them.

The publication Jornal de Borda first understood itself as an anarchist newspaper after Issue 4, within the anarchist language, ethics, and aesthetics research. In its inception in March 2015, it was said to be a journal linked to Latin American autonomous feminism, a branch of feminism that is anti-establishment and seeks to act independently from government institutions. It was launched in a "Feira Plana", an event for independent publishers, by the small publishing company Tenda de Livros. The idea was to create a contemporary art journal with the participation of Brazilians and other Latin Americans. At that time, O Borda still had a place: that of the artist's book, and it was based on the printed thinking of the Mexican conceptual artist Ulisses Carrión. In his classic work "El Arte Nuevo de Hacer Libros" (The New Art of Making Books), Carrión (1975) questions the book as a literary object linked to a name, an author: the one mentioned on the cover. That inspired the Jornal de Borda to be deliberate in its collectiveness.

Jornal de Borda was born from the perspective of thinking about narrative sequentially and the space on the page to be printed, giving the text and the image the same weight. In doing so, conservative and modern aesthetics are juxtaposed, as shown in Figure 1 — a conservative newspaper format featuring a black square, a symbol of modern and abstract art3. Even though the full name was Jornal de Borda, the periodical was called by its nickname O Borda, which was used in two issues: the seventh and the 10th. O Borda (without "Jornal de" and with the inclusion of the masculine definite article "o") refers to the past century's anarchist periodicals, such as A Plebe, and A Lanterna, which had their names thought of with a definite article and a noun, but with the strangeness of a gender disagreement, since the correct would be "A Borda". Nevertheless, the nickname was always masculine due to the masculine word for newspaper.

Source. Tenda de Livros (by Fernanda Grigolin)

Figure 1 A physical copy of the Jornal de Borda, Issue 2 (2015). Cover by the artist Fabio Morais

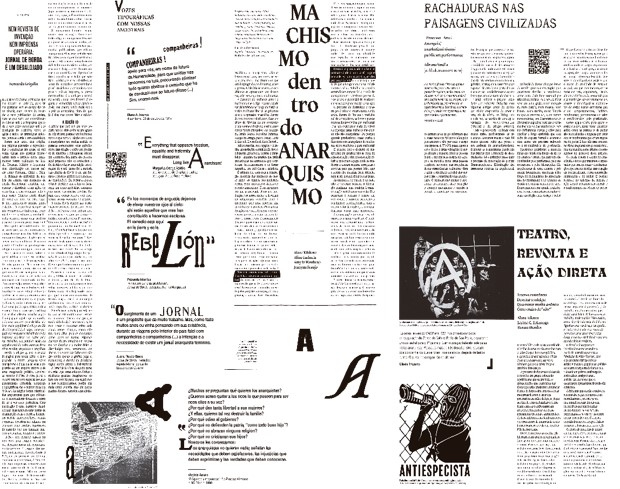

Figure 2 is the middle pages of the 10th edition as if we were reading it open. The middle features text about chauvinism in anarchism, written collectively by anarchist militants. Although the format at first glance seems conventional, it is dissident in content and detail. For instance, while the columns may seem ordinary, a closer look shows the alignment is not. The "a" is a play on the usual drop cap but eventually takes on the meaning of a symbol of anarchism. There are quotes from anarchist women like Margarita Ortega Valdés (Mexican), Juana Rouco Buela (Argentinean) and Petronila Infantes (Bolivian). The design of the pages — the titles and their typography — leads the reader's gaze around the page. The relationships between content, format, participants, and visuality are as important as the disciplines of the publication, which is the epitome of transdisciplinarity in print.

O Borda and Facsimile Editions

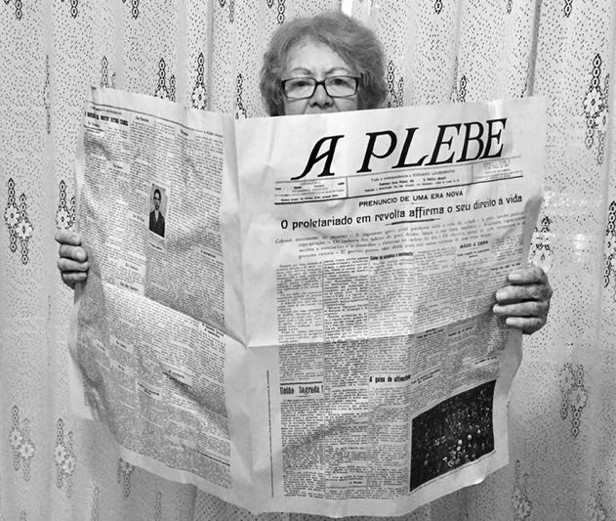

O Bordais an anarchist newspaper of the 21st century inspired by the content and format found in the newspaper A Plebe (Figure 3), from 100 years earlier. Line-and-column study and research activate a contemporary reading of a newspaper from past anarchist print culture.

Source. Tenda de Livros (by Fernanda Grigolin)

Figure 3 A woman is holding a facsimile edition of A Plebe, taken in 2017

A Plebe was an anarchist periodical published in Brazil for 34 years (between 1917 and 1951), having Edgard Leuenroth as its main director. It was born in a rather large format, 53.5 × 37 cm (closed) on four pages (one folded sheet), having a size smaller than an institutional newspaper from that time, that is, O Estado de S. Paulo of the same general period (63 × 45 cm).

By overlapping the covers of the 1917 A Plebe and 2021 O Borda issues (Figure 4), the formal citation of both periodicals and their columns can be noted. It is worth mentioning that, in 2017, the cited issue of A Plebe had already appeared as a facsimile edition in Issue 4 of O Borda, whose theme was archive, memory, and power.

Source. Tenda de Livros (by Fernanda Grigolin)

Figure 4 Overlap of A Plebe, from 1917, with O Borda, from 2021

A cross-century homage to the predecessors of this ideological movement has an artistic and political purpose. Although we live in a new technological paradigm, much of the social issues that arose at the turn of the last century still exist today. We have not only shifted centuries but also millennia. The fact that we still face issues of racism, sexism, poverty, and devastating industrial practices is only exacerbated by their persistence into the new era, the 2000s, which have often been portrayed as a beacon of advancement and development by contemporary entrepreneurs and defenders of liberalism (the socio-political doctrine behind today's economic system). As a society, we have not solved issues as much as we created new ones, most notoriously our impending climate collapse. Therefore, a visual tribute to militant ancestors is an artistic offering that energizes a political resistance going forward.

The sixth issue of A Plebe (from 1917) is a place of expression; it is related to a community in action that has a common objective: the right to life. It is also a place of registering memory since it is incumbent on workers to tell their own story, be it through text, its spatial organization on a typographic page, or even adding a crucial element: a photograph taken at a strike, a symbol of urgency and therefore placed on the first page. A photo "proves", or at least used to prove, the existence of an event and the actions of thousands of people — that it happened. In the era of fake news and deepfakes, it has become abundantly clear that technological advances, such as more and better digital cameras, have not led to wider distribution of truth. Thus, it is still not enough to say that there was a crowd or visually show the aspect of the crowd that accompanied the burial of comrade Martinez, when stopped at 15 de Novembro street.

The printed format was an effective practice for disseminating information about events and their magnitude to as many people as possible. After its printing, the newspaper was a place for circulating ideas and a powerful instrument of anarchist propaganda among those in São Paulo and their comrades from other cities or countries.

Below (Figure 5), the following texts are centered: "A Plebe" (in italics, alluding to the movement); "Foreshadowing of a new era" (in capital letters and another font); "The proletariat in revolt asserts its right to life" (in another font and larger size, also in capital letters, with a triple line). Also centered with the use of two consecutive lines are the following sentences, which we could say stand first: "Colossal protest movement — The imposing general strike paralyzed all life in the city — The starving plebs carried out the expropriation — The brains of the people's thieves let loose their vandal rage — Murders, beatings, robberies in associations and homes — were in the order of the day — The workers, despite everything, achieved their first victory — It is necessary, however, to be alert, so as not to be victims of a vile betrayal".

Source. Public archives of São Paulo state

Figure 5 A Plebe newspaper, Year 1, Number 6; July 21, 1917

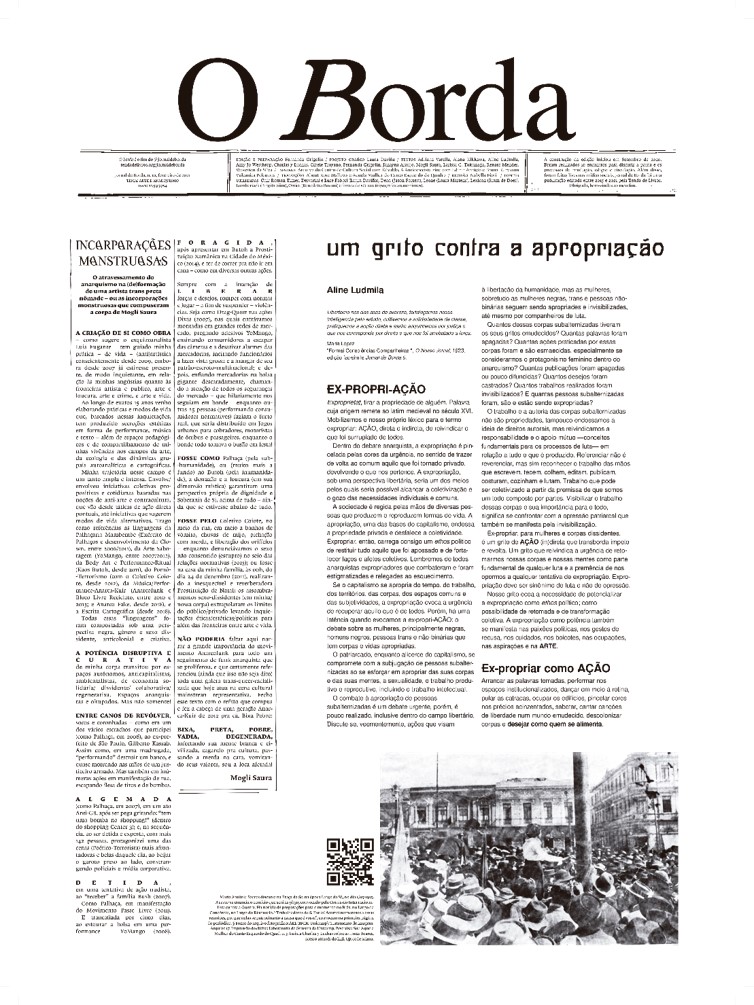

A Plebe is a place both of registering and expression, and it is not only linked to news and fact. Its proposal and printed possibilities are of daily use by a community in action. For the last Jornal de Borda, O Borda (Figure 6), the themes were art and anarchism to invoke action in the community, as publications of this nature once did. The new logo, designed by Laura Daviña, is a hybrid of the original Jornal de Borda logo, developed by Lila Botter, with the A Plebe logo. Daviña also developed the graphic design for the edition, which is a conversation with the past through visual, ethical, aesthetic, and printing tools. The texts were made using A Plebe typographies or others designed by Daviña, such as the Luce Fabbri font. The unusual format added rhythm to the text in columns and the spatiality in using voids.

Source. Tenda de Livros (by Fernanda Grigolin)

Figure 6 Cover O Borda, from 2021. The front-page texts are about dissident bodies, especially trans bodies, by Mogli Saura; the expropriation by Aline Ludmila. There is an image of Maria Antônia Soares in a speech on May 1, 1915

The periodical was created based on the size and format of A Plebe to honor, reference, and passionately demonstrate that through publishing, we can take back the narrative of our own lives and occupy a space routinely denied to corpas in the mainstream — to expropriate, in the anarchist sense of the word (Bayer, 2015). In Aline Ludmila's (2021) words, printed in O Borda: "expropriation as a power ( ... ) is expressed in political passions, in gestures of refusal, in care, boycotts, occupations, aspirations, and ART" (p. 1). The themes were expropriation, death to genius, artistic making, theater, insurgent corpas, anarchist women, and chauvinism within anarchism.

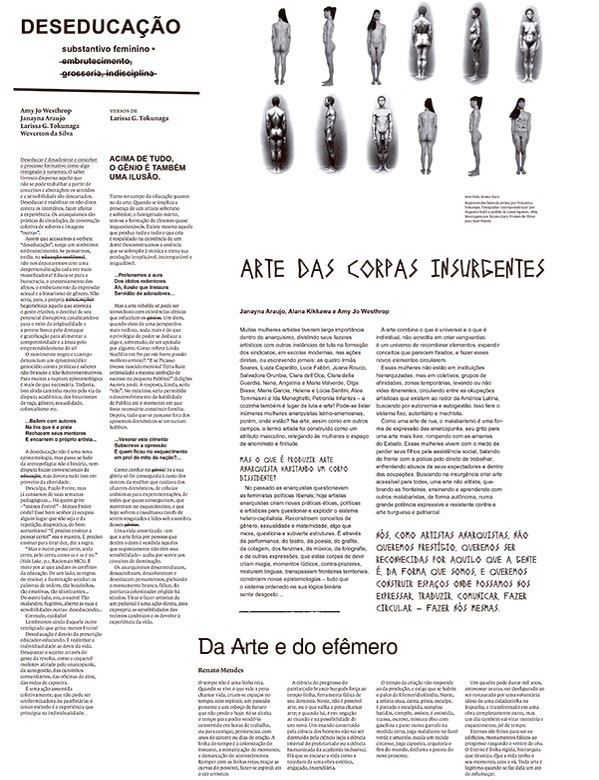

The last O Borda is a place of shelter for texts and visualities that converged during conversations and were then set up on pages. The subject of corpas and their survival was discussed by Mogli Saura, Adriana Varella, and Bruna Kury (Figure 7). Corpas, the feminine expression of the physical and/or intellectual body, are marginalized in a myriad of ways and, in some cases, brutalized and killed. Through art, these contributors asked for a place where the trans, fat, disabled, poor, black, queer, displaced, and dissident bodies can safely occupy to survive a hostile system, revolt, and find affection.

Source. Tenda de Livros (by Fernanda Grigolin)

Figure 7 Back cover O Borda (2021), visual work by Bruna Kury (top right)

The archives of Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth and Cedinci were important sources of research for the facsimile editions of Jornal de Borda. A Plebe (from 1917), O Nosso Jornal (from 1923, ran by the Women's Emancipation Group), and Nuestra Tribuna (from 1922, ran by Juana Rouco Buela) had facsimile editions inserted into the Jornal de Borda — they were reproduced in the size of the newspaper of that time, only not in the same printing technique. The A Plebe was typographic, and the 2017 edition was a scanned version and reproduced with the use of a modern printer.

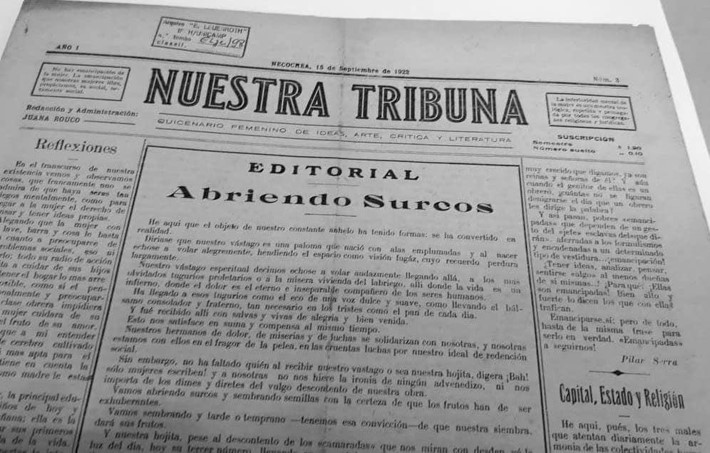

The newspaper Nuestra Tribuna's editorial practice is an example of transnational editing. It was born in Necochea in August 1922 and closed in Buenos Aires in July 1925. Buela was a transnational editor and thinker of printed pages who looked at the process and project and saw a public vocation in a newspaper. She traveled all over Argentina in the early 1920s to understand anarchist women's needs, after which she released Nuestra Tribuna. The newspaper (Figure 8) had four pages, and each page was divided into five columns. It was biweekly and had a circulation of approximately 2,500 copies.

Source. Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth, Institute of Philosophy and the Humanities, State University of Campinas

Figure 8 An original edition of Nuestra Tribuna

The periodical, born from the process of listening to women's needs and intense publicizing before printing, starts with 1,000 women as subscribers. In the first edition's editorial, Nuestra Tribuna states it wants to reach out and act jointly with the anarchist movement in neighboring countries, citing Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Peru. The newspaper prioritized articles written by women, such as anarchists Soledad Gustavo, Teresa Claramunt, Federica Montseny, María Magón, and Maria Antônia Soares, preferring not to have pseudonyms as signatures.

To think about collective anarchist publications is to think about Juana Rouco Buela. Her way of opening furrows and planting printed seeds allows us to come across her words and teachings alongside other women who edited and wrote for the paper. In short, Juana Rouco is an ancestor of one surviving publishing practice.

A Plebe and Nuestra Tribuna are periodicals that inspired the last issues of O Borda because their purpose has always been to seek out artists who go beyond what is formally considered art and anarchists who go beyond hegemonic agendas. The separation between art and life, art and politics, serves only a market, and its circulation strategy is based on the distribution for sale and profit. In editorial production, publishing communities with a political purpose implement innovative (artistic) circulation-related solutions. Moreover, publishing as a form of resistance and survival usually generates a collective and cross-border bond, referred to as Latin American affections. Therefore, publishing is a form of resistance and survival related to revolt, and when art is not associated with revolt, it is a servant to and an accomplice of capitalism, an instrument of order with no links to freedom (Pelloutier, 1896).

The Opinion of Those Who Built It: How O Borda Is Seen

With whom does O Borda want to collaborate? This question has always been important in every edition, so the paper's contributors could summarize the dialogue over the publication. Brazilians, Mexicans, and Chileans made up the majority of the contributors to the last edition, which was the one where the decision-making processes of production, edition, and circulation were discussed during the meetings.

In October 2021, a form was sent by email to the participants. The colaborators were Aline Ludmila, Bruna Kury, Fabio Morais, Fausto Gracia, Ingrid Ladeira, Janayna Victória Araujo, Karina Francis Urban, Larissa Guedes Tokunaga, Lucia Parra, Mane Adaro, Mogli Saura, Renato Mendes and Weverton da Silva. In excerpts from some of their answers, it is possible to see what the production of O Borda means to the participants as artists (in Section 1) and as political activists (Section 2). Section 3 shows what publishing with corpa means to those who identify as such.

Section 1

As an artist, Larissa Tokunaga considers O Borda a collective exhibition: "it is a handcrafted stitching of creative gestures that pass-through corporeality and immanence. The artistic-making is in the publisher's own conception. ( … ) Content and format are so inextricable that Jornal de Borda overflows the frames of a conventional work of art. Visuality is a political gesture that communicates in tune with texts".

Fabio Morais describes it as an even more fluid artistic process: "in fact, I see Jornal de Borda as an editorial action open to contingency, which has no problems changing its focus, format, agenda, etc. Depending on the context and the environment, the editorial objectives change or need to change. So, sometimes I could see it as an exhibition, sometimes as an artist's newspaper, as an aesthetic-militant platform, as a platform for research and historical recovery for dialogue with issues of the present, etc., something more about 'being in a place' than about 'being something'".

Fausto Gracia connects the geographical diversity of the publication with its artistic fluidity: "I really like the participation of Latin American artists. It connects processes and experiences in addition to geographic ones".

Section 2

Ingrid Ladeira agrees: "I believe that Jornal de Borda goes far beyond an artist's newspaper; it is a collective expression (of different groups and agents) that brings together a series of interests and struggles".

Weverton da Silva, writer, highlights the anarchist nature of the publication: "the main reason that led me to O Borda was precisely the fact that it was an artistic and anarchist publication. This relationship seemed absolutely fruitful, although I could not imagine the paths that would be followed. As I tried to learn more about O Borda, I realized that its borders crossed the written and visual arts, political militancy, the fields of sexuality, and the history of anarchist women in Latin America, among other dissident themes. Thus, more than the mere daily information of common periodicals, O Borda is a dialogue between political activism and artistic creation".

Lucia Parra, a researcher and member of Centro de Cultura Social in São Paulo, describes the unclassifiable nature of the publication as a tool for amplifying marginalized voices: "I don't know of any other newspaper like the Jornal de Borda, so I sometimes think it's not classifiable. And it is exactly with dissenting corpas that it aims to bring forth this discussion in its issues".

Tokunaga sees O Borda as: "a queer/cuír manifesto that runs against the current hegemonic publishing patterns. That implies bringing dissident corpas and hands to circulate other ideas".

Section 3

Saura expands on what publishing with corpa means: "I think that being with dissident corpas requires very specific intersections and locations and an engagement aimed at dissident perspectives, as from their existential margins and issues. 'Dissidence' is many things; which dissidence? Where? When?".

Gracia shares the same opinion: "O Borda follows up very updated processes on the different forms of transit of dissident corpas. It is part of the very search to get out of hegemonic discourses".

Bruna Kury says: "there is a particularly important attempt at these approaches, which is not that simple either. But the search for being close to other dissident corporeality is crucial in the struggle. My suggestion is to think about a publication for/with people with disabilities".

These testimonies reveal the relationship between publishing with corpa and the political power of Latin American affection. Identifying as corpa, both in physical and intellectual body, is embracing each other despite differences, bonding over the shared experience of feeling repelled by a global paradigm that brutalizes dissidence. As such, there are no borders between the visual and the textual expression, the political and the personal realms, or the artistry that hangs on the wall or fills up your hands. The newspaper travels not only through time but through countries, disciplines, and lives.

Conclusion: Surviving Corpas and Their Gestures as Revolt

The appearance of a newspaper is a purpose that requires much work. However, as I had been thinking about it for many years, during my travels in the countryside, I spoke with comrades about the intention and need for a feminine anarchist newspaper. (Buela, 1964, p. 101)

O Borda has fulfilled its role in its 6 years of existence in playing a part in this surviving practice, but some of its editorial questions remain open: how to think about the circulation of a printed publication beyond spaces such as bookstores and galleries?; what is it like to publish in Brazil and Latin America with the bodies that write and produce art?; must there be inclusion in linear art history to become an artist?; must there be a discussion about European history to become anarchists?

Creating a newspaper is still a demanding practice in which text, editing, layout, and page sequencing should be considered. A publication goes far beyond the juxtaposition of information; there is a printed thought. The creation of independent publications is neither scrutinized by the art market nor the publishing market. As such, publications are linked to the public vocation of editing and circulating ideas through transnational networks.

Transnational networks set up in the past are related to current surviving practices. To see that these publications existed in the 1800s and early 1900s is understanding the crucial role that anarchism has had for the printed practice, editorial thinking, handcrafted publishing, and artists' publications at large. The newspapers mentioned in this article represent how art can be a political tool against state repression and how politics can be an artistic tool in finding purpose and innovative dissemination strategies despite the rigid or exclusive (Eurocentric) art institutions.

The artistic value of aesthetics is a social construct in a time and a place. Therefore, the subversive character of publications will always escape the commodification of taste and the confinements of academic disciplines. In discussing decoloniality and the linearity of a Eurocentric history, we expropriate material, intellectual and artistic narratives that permeate all aspects of our lives — all of which are embodied by the artist's publication. Hegemonic narratives can be degrading and brutal to marginalized peoples, and by publishing with corpa, an expression of revolt and affections has the potential to restore dignity. This process can not be reduced to either art or politics. It is magnificently both.

Publishing with corpa is pivotal to visual culture. Leaving dissident bodies out of the narrative around artists' publications perpetuates hegemonic values which marginalize people through "interlocking systems of domination" (M. Hooks, 2015, p. 21), namely colonialism, capitalism, chauvinism, and so on. Perhaps presenting a new narrative — of interlocking art, anarchism, and the printed page — will not only teach us about anarchist practices but also widen our perspectives through a diverse and true reading of visual culture and, by association, humanity.

text in

text in