Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versão On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.12 Braga dez. 2023 Epub 30-Jan-2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.5202

Thematic Articles

The 21 Characteristics of Advertising Communication in the 21st Century: The Supremacy of Virtuality and Visuality

1 Centro de Investigação em Comunicações Aplicadas e Novas Tecnologias, Universidade Lusófona de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

Com a evolução tecnológica, a comunicação online começou a fazer parte integrante do quotidiano das marcas e dos consumidores, preponderância que sofreu um acérrimo acréscimo com a pandemia. Inclusive em Portugal, apesar de apresentar valores mais analógicos, comparativamente com a média europeia. Presentemente, é difícil de delinear uma estratégia sem incluir a esfera virtual, dada a inevitabilidade da digitalização das mensagens. O mercado sofreu mutações e o internauta ganhou um protagonismo sem precedentes, como ativo, independente e empoderado produtor de conteúdos: o paradigma muda, com o surgimento do prosumer, que se afastou de uma vertente meramente recetora, passiva e contemplativa. Consequentemente, com a perda do monopólio comunicacional das insígnias, prevalece a troca de opiniões entre as comunidades virtuais, compostas por pares, em que se assiste à passagem da confiança das marcas, através da publicidade tradicional, para os próprios indivíduos. Subsistem circuitos de partilha informacional voluntária e informal, em que sobejam experiências personalizadas, tornando-se numa destacável, credível e orgânica fonte de influência.

Por outro lado, encontramo-nos numa sociedade maioritariamente visual, importância galvanizada com o surgimento das redes sociais, repletas de estímulos estéticos. Valoriza-se, primordialmente, o conteúdo imagético, através de uma argumentação iconográfica, em detrimento de uma retórica das palavras, nomeadamente na publicidade. Esta prevalência da imagem ocorre devido ao seu maior potencial emocional, simbólico, recreativo e motivacional, o que acaba por se repercutir numa maior capacidade para influenciar os processos de consumo. Destacam-se, portanto, as práticas audiovisuais, particularmente o vídeo, por proporcionar, mais facilmente, a visibilidade e a partilha de uma mensagem. São várias as mudanças implícitas numa era volátil, as quais urge conhecer. Para o efeito, operacionalizámos uma revisão bibliográfica holística e contemporânea, etapa que permitiu identificar as 21 características principais da comunicação publicitária em vigência em pleno século XXI, evidenciando-se a virtualidade e a visualidade.

Palavras-chave: publicidade; virtualidade; visualidade; contemporaneidade

As technology has evolved, online communication has become an integral part of the daily lives of brands and consumers, a preponderance that increased dramatically with the pandemic. This is the case even in Portugal, despite it showing more analogue data consumption compared to the European average. Nowadays, it is difficult to outline a strategy without including the virtual dimension, given how inevitable the digitisation of messages is. The market has changed and internet users have gained unprecedented prominence as active, independent and empowered content producers. The paradigm has shifted with the emergence of the prosumer, who has moved away from a merely receptive, passive and contemplative role. Consequently, with the loss of the communicational monopoly of brands, the exchange of opinions between virtual communities, made up of peers, has come to the fore, with trust passing from the brands, through traditional advertising, to individuals themselves. There are circuits containing voluntary and informal information sharing, in which personalised experiences abound, to become an outstanding, credible and organic source of influence.

On the other hand, we find ourselves in a mostly visual society, with the importance of this galvanised by the emergence of social media, which are full of aesthetic stimuli. Content involving images is prioritised, through iconographic argumentation, to the detriment of verbal rhetoric, particularly in advertising. This prevalence of image is due to its greater emotional, symbolic, recreational and motivational potential, which ends up having a greater ability to influence consumption processes. Therefore, audiovisual practices, particularly video, stand out because they make it easier to see and share a message. There are indeed many changes which form part of a volatile era, and it is necessary to be aware of them. To this end, this article contains a holistic contemporary literature review, that has enabled the identification of the 21 main characteristics of advertising communication in use in the 21st century, in which virtuality and visuality stand out.

Keywords: advertising; virtuality; visuality; contemporaneity

1. Introductory Reflections

The aim of this article is to uncover which path advertising discourse will take, at a time when the ground for change is fertile as a consequence of a century marked by daily unpredictability, an already deep-rooted uncertainty which the COVID-19 pandemic emphasised. This volatility has had an impact on all fields, and in particular the communications area. The aim is to find out what the main characteristics of current advertising are. The study detected a total of 21 elements, of which the centrality of digital and image-based communication will be highlighted. Not investing in digitisation and visual content would therefore result in an anachronistic and obsolete brand strategy. Indeed, given this, traditional advertising and its textual aspect seem to be losing ground in a society that is mostly online and image based. This issue is conceptualised here by reflecting on the major challenges facing contemporary advertising discourse. To this end, a bibliographical review was carried out, and there is an attempt to ensure that that was pertinent, comprehensive and recent, so as to be able to provide relevant clues for future research on the different topics under analysis.

2. The Importance of Digital Communication

Communication has undergone substantial changes over the last few years, mainly due to technological evolution, in particular with the emergence of the networked society at the end of the 20th century (Magalhães & Marôpo, 2016), namely the popularisation of the world wide web which took place in the 1990s (Ribeiro & Assunção, 2022). From then on, being social has involved having a virtual presence: “not being on digital networks means not existing” (Oliveira, 2018, p. 65), which is why “analysing individual forms of beingin the 21st century involves ( ... ) understanding their behaviour on digital networks” (p. 62). This tendency extends to brands, which are setting forth new communication practices based on digitising content1 (Carrera, 2015; Mesquita et al., 2020; Santos, 2021). These consist of a flow of dialogue in which interaction is continuous (Scafura, 2020; Scrofernenker & Oliveira, 2018; Sousa et al., 2020). This is one of the characteristics of a fragmented contemporaneity: a “liquid” era reigns, based on the tyranny of the moment, as opposed to the past, when solidity and irrevocability were unquestionable, as a “solid” phase, in a dynamic of eternal absolutism (Bauman, 2000). Advertising also mirrors this fortuitousness, as it is an area in transition, reflecting the immersion of new movements and an emerging paradigm (Santos, 2022).

2.1. Digital Communication in Portugal

In the online context, the Meta platforms (Facebook, Facebook Messenger, Instagram and WhatsApp) and Google (YouTube) stand out. Of these, it can be seen that Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube are the most used by the Portuguese for various purposes. Instagram has emerged as the social network showing the greatest growth, unlike Twitter (Cardoso et al., 2022). However, despite the greater democratisation of access to information and communication technologies, Portugal’s figures in the European context are rather “analogue” when compared to the global market (Cádima, 2019; Lapa & Vieira, 2019). Portugal shows constant weaknesses in relation to the information development of most European countries, and has lower rates of internet access and use among households (Lapa & Vieira, 2019).

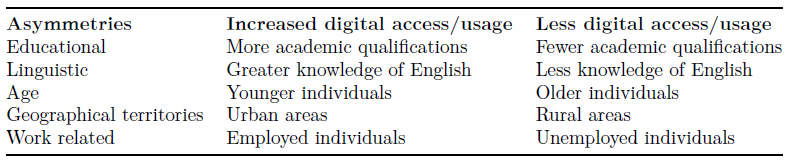

This situation occurs because Portugal has fewer socio-economic and cultural resources than the European average. When taking into account traditional indicators of social inequality and exclusion, a digital divide exists. This is a trend, as Westernisation has repeatedly demonstrated persistent disparities, particularly in unequal societies such as Portugal. Let us take a look at the main explanatory variables for the aforementioned national gap, and observe that school, language and age differences are at the top of the table (Lapa & Vieira, 2019; Table 1).

These are differences that distinguish the digitally included from the digitally excluded. What is more, internet users with more socio-economic, cognitive and cultural resources use technology more often as a tool for information and as a way of strengthening social ties, while the more underprivileged internet users are mostly looking for entertainment. Indeed, it is the elderly, far from urban centres, as well as in low-skilled sectors or in those excluded from the labour market (the cultural capital indicator - schooling - is more significant than economic capital - income) where we find the most revealing cases of info-exclusion, which distance Portugal from other partners on the same continent (Lapa & Vieira, 2019). This data shows that, contrary to what might be expected, technology does not always act as a decentralising and levelling force for hierarchies and power, despite it being an enabler of social mobility and of new opportunities in the lives of individuals (Lapa & Vieira, 2019). Growing technological investment seeks to respond to the challenges posed by an increasingly digital economy, and government policies and guidelines in Europe tend to promote the mastery of these types of skills in the population. Nevertheless, digitisation in Portugal is tendentially increasing, and by 2025 it is expected to be close to the European average of users (Baptista & Estrela, 2019).

The emergence of COVID-19 amplified the significance of digital platforms (Scafura, 2020). This was to be expected, given that technologies are particularly seen as an alternative to scenarios involving economic crises such as the present one (Saturnino, 2020): “the global shocks of last few years have galvanised ( ... ) to refocus on digital” (Newman et al., 2022, p. 30). Although digitisation is one of the inescapable characteristics of present-day society, the pandemic outbreak reinforced its importance and hastened its implementation by two/three years. Of note has been the investment in social networks, particularly Facebook and Instagram, as well as websites. As such, COVID-19 had a more negative impact in companies that have not adapted their business to this virtual reality (Ribeiro, 2020). In short, between 2020 and 2021 the overall pandemic effect was +33% in fixed data traffic, +23% in fixed voice traffic and +11% in mobile voice traffic (Autoridade Nacional de Comunicações, 2021). As a result, internet access, online shopping and corporate virtual presences increased. In other words, the pandemic accelerated digital transformation in Portugal.

2.2. Virtuality and Advertising: The Rise of Prosumption

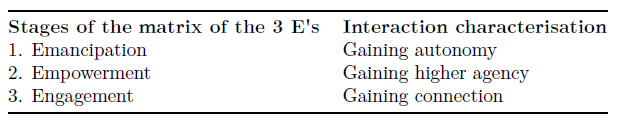

With the aforementioned digital development, the paradigm has shifted and conventional advertising has undergone a setback, losing its communication monopoly due to the emergence of a new, independent and empowered agent, namely the prosumer. Prosumption is a concept that emerged in the 1980s, through Alvin Toffler (1980/1984), and which is a result of a merger of production and consumption2. The user is thus mobilised and emancipated, going from being a passive, contemplative and inert public (web 1.0) to being an active, participative and reactive one (web 2.0): “they are no longer a faceless statistic in a report” (Wheeler, 2008, as cited in Leal, 2017, p. 22). Thus, there has been an accumulation of roles, since the internet user is both a consumer (receiver) and a producer (sender) of content (Cardoso, 2023; Toffler, 1980/1984), through user-generated content, in a system that is less demanding, intrusive, anonymous and partial - properties associated with offline advertising discourse. This has triggered a new, hybrid player in the market, who has gained greater power in the interactions which have been established within the virtual arena (Kotler et al., 2016/2017). And what has emerged within this collaborative and equitable exchange panorama is the following matrix of the 3 E's, the terminology adopted to characterise the emerging dynamic (Table 2).

The aforementioned transformation has brought about endless changes in the relationship established between individuals and brands, as the opinion of peers (domestic influencers) has begun to be valued. Consumer trust has been retained, where “the wisdom of the crowd” resides, and circulates in virtual communities, even though this was once concentrated in the advertising discourse of brands, which are now the target of greater questioning and scepticism. Peer-to-peer networks have emerged, that is, circuits of voluntary and informal information sharing, the reports, testimonies or advice from which are seen as more reliable (Kotler et al., 2016/2017; Pereira, 2022). Mediated experiences, such as those provided by advertising, are losing importance compared to personalised ones, which are gaining significance, and becoming a greater source of influence (Kotler et al., 2016/2017): internet users “ask strangers for advice on social networks and trust them more than advertising and expert opinions” (p. 36). This ultimately has consequences: “casual conversations about brands are now more credible than targeted campaigns ( ... ) with specific targets” (Kotler et al., 2016/2017, p. 31), something “advertising can never replace” (p. 66).

The ease, accessibility and free nature of online platforms have led them to become privileged spaces for interaction and social inclusivity for users (Pereira, 2022). In this way, it is possible to identify a process of individualisation, in which personalisation and democratisation prevail - the opinion of internet users gains prominence - which replaces institutionalisation, where massification and hegemonisation prevailed - in which brands and advertising discourse had a monopoly on communication, whereas nowadays, “we can all communicate”

(Cardoso, 2023, p. 199). Indeed, offline advertising discourse is losing ground “as consumers no longer welcome traditional, non-targeted communication and advertising with open arms” (Pereira, 2022, p. 48). In this way, the advertising message will be passed on in a more organic way, through social influence and word-of-mouth (Pereira, 2022). Emerging narratives are being seen as “the new advertising” and hashtags as contemporary slogans (Kotler et al., 2016/2017). In this recent dynamic, in which a logic of “platformisation” stands out, the image component is emphasised, since the digital medium has image as its central element, leading to a “screenovision”, which “is the sum of many people watching, tele-being, tele-sharing and tele-using, making it possible to boost the economy of attention” (Costa & Martins, 2023, p. 2).

3. The Preponderance of Visuality in the Present Day

Present-day society can be equated with a “civilisation of visuality” and iconography, given the aesthetic significance with which it permeates the social fabric, filled with visual stimuli, as part of an era which is performative (Barroso, 2017; Berni & Accorsi, 2019; Carapito, 2010; Ferreira, 2019; Mateus, 2016; Santos, 2019; Steagall, 2020), such that “as to the thesis that the West is founded on the word, the screen is further suggested as the producer of a new individuation, the reason for a shift from the culture of the word to the culture of the image” (Costa & Martins, 2023, p. 5). In effect, a cinematic and staged vision of a hedonic everyday life is encouraged: “a purely aesthetic dimension which transforms everything into entertainment” (Ferreira, 2018, p. 37). This panorama ends up creating a new individual profile: Homo ecranis (Oliveira, 2018). Indeed, we are witnessing the transition from Homo sapiens, a product of the mastery of writing, to Homo videns, given this plastic sovereignty (Sartori, 2000, as cited in Barroso, 2017). This prominence is particularly visible in young people. This is “generation C - Connected” (Oliveira, 2020, as cited in Pereira, 2022, p. 30): “born and/or raised within an evolved technological bubble, the must-see generation” (Burnay & Vicente, 2023, p. 2) unleashed from anonymity (Costa & Martins, 2023).

Curiously,

human beings are literate when it comes to reading written texts and then interpreting them, but there is no requirement to be literate when it comes to non-verbal texts, and it is believed that their interpretation should occur naturally, without any other readings or questioning. (Petermann, 2006, p. 2)

That's why this is “left to intuition and chance. Among human communicational means, the visual establishes itself as the one lacking a clear and precise set of norms and methodology” (Aumont, 1990, as cited in Steagall, 2020, p. 58). Pictorial literacy does not follow a specific system, as verbal language does (Steagall, 2020): “the imagery is more visceral than the textual, which is conventionalised” (Ferreira et al., 2008, p. 10), “images constitute a kind of primary code that refers more directly to the mind’s interpretations and correlations” (p. 10). Perhaps because its strength comes from being a specific, simplified, intuitive, defined, condensed, concrete, organic object and, as a representation of reality, it allows for anchoring, moving away from the arbitrariness of the word: “if descriptions ( ... ) compel mental representation, physical images constitute something real” (Ferreira et al., 2008, p. 7).

In addition, images are one of the oldest ways through which humanity communicates, having been present since prehistoric times, before the emergence of writing: “we are visual beings” (Lima, 2013, p. 15). It is therefore possible to envisage a scenario that boosts audiovisual consumption: “a simplified cartography necessarily includes phenomena such as the ‘screenisation’ of society” (Burnay & Vicente, 2023, p. 3). This prominence can be transposed to communication, particularly advertising, where the plastic aspect is one of the dominant supports, and there is a cultural convergence around digital imagery (Costa & Martins, 2023).

3.1. The Primacy of the Imagetic Dimension in Advertising Discourse

The advertising message is hybrid, with two constituents as discursive resources (Berni & Accorsi, 2019; Leal, 2017; Veríssimo, 2021a): the text (name, slogan, etc.) and the image (logo, typography, etc.); it can be composed of only one of the elements, in isolation, or both, within a logic of complementarity. However, at present, the primacy of graphics is evident, there being a postmodern obsession with the image (Ferreira, 2018; Martins et al., 2020), in which the pictorial dimension plays a prominent role (Ferreira, 2019), as a driving force (Salbego, 2007): “organisations increasingly turn to images in an attempt to find a place in the minds and time of users” (Martins et al., 2020, p. 337), “a large portion of advertising nowadays has little verbal content and instead relies on images for its argumentativeness” (Mateus, 2020, p. 10), “images have a fundamental place in advertisements” (Berni & Accorsi, 2019, p. 2), “the visual component is important for capturing attention and creating a connection in the sensory field that leads the public to identify with the brand” (Leal, 2017, p. 26), since what is seen is more likely to influence than what is stated (Allen & Simmons, 2017, as cited in Leal, 2017, p. 26), especially on digital platforms: “what on non-digital social networks is often achieved through words, on digital social networks is all achieved through images or videos” (Costa, 2020, p. 79).

The particular focus on this content format is due to the superior symbolic capital that characterises it, dominated by sensory and social appeals, compared to the impact obtained through the textual dynamics of a piece of communication (Araújo & Lopes, 2013; Leal, 2017; Veríssimo, 2021a): “the image used in advertising creates fantastic worlds where products gain much more than their use value” (Salbego, 2007, p. 1), “the meanings of the use of attractive images seek to go further by connecting emotionally with the target” (Escalada, 2018, p. 136), which is why “the visual element within an advertising campaign is often the first to arouse attention to the message” (Steagall, 2020, p. 3), in addition to its greater speed in understanding what has been transmitted (Lima, 2013). Contemporary ephemerality reflects the importance of an instantaneous apprehension of discourse, regardless of its typology (Mateus, 2016). In fact, advertising functions as a dreamlike reservoir, emphasising the symbolism and intangibility of goods through emotion, cultivating relatability, given the impact this has on consumption processes, as a powerful motivational tool (Santos, 2022; Volli, 2003/2004): “the advertising narrative explores positivity, dissipating the consumer’s weaknesses and exacerbating their narcissistic side” (Santos, 2013, p. 49). There is thus a rhetoric of the image that captures attention, stimulates the imagination and leads to persuasion (Costa & Martins, 2023; Ferreira et al., 2008; Mateus, 2016; Veríssimo, 2021a): “it is through images that, in advertising, linguistic messages gain their true dimension and meaning ” (Ferreira et al., 2008, p. 8). In short, communication tends to arise from the merger of image and emotion, in which audiovisual advertising seeks to cause commotion (Galhardi, 2019), giving rise to “reactions in a more natural manner” (Ferreira et al., 2008, p. 10). As a result, the dimension of images is no longer seen as a mere illustrative resource, but as an active element in the rhetorical process. Indeed, the idea is present in the popular expression: “a picture is worth 1,000 words”.

3.1.1. Video: A Privileged Narrative

In considering narratives that generate a greater return, the video format should be highlighted. The algorithms of this ludic format can be fine-tuned to obtain greater reach and it has an outstanding propensity to generate engagement, adaptable visualisation and rapid and smooth sharing, particularly through a viral effect, which allows it to obtain greater visibility through its potential creativity and spectacularity: “ideas and opinions spread through networks of individuals in the same way that diseases spread through populations” (Tarde, 1890/1978, as cited in Costa & Martins, 2023, p. 20). Arousing emotions in the public, thereby creating a strong impact, can lead to sharing (Araújo & Lopes, 2013; Costa & Martins, 2023; Leal, 2017; Lopes, 2015). Indeed, the recurrent use of this tool has grown significantly, given the greater ease with which it is able to trigger an emotional response from the consumer. The emotional element more readily stimulates persuasion, influencing consumption practices as a consequence, hence its broad capacity to encourage purchasing processes (Araújo & Lopes, 2013; Costa & Martins, 2023; Leal, 2017).

Costa and Martins (2023) explain how the process is carried out effectively, guaranteeing user retention and loyalty: “the relationship between video and digital platforms is that, unlike ( ... ) any television advert ( ... ) there is the advantage of the image-movement appearing through the existence of algorithms which collect emotions, tastes and preferences” (p. 5). In other words, “through algorithmic techniques, tendencies are made known, as well as screen and digital network usage habits, profiles, histories and everything that is necessary for a maximised projection in front of the subject’s eyes” (p. 5). Furthermore, the fact that it promotes what is common among a group of viewers, creating consensus between “equals” and, conversely, tension between “opposites”, also contributes to the success of this format (Costa & Martins, 2023). Another factor facilitating the popularity of this format is the fact that innovations in the technologies used to produce this type of file are becoming less and less expensive, complicated and time-consuming (Simões & Augusto, 2019). What is more, the remarkable speed with which this type of message is propagated, which is practically immediate, helps us to understand the success achieved, as we are dealing with a society that values the immediacy of content (Costa, 2020; Kotler et al., 2016/2017).

Their popularity has meant that advertising videos are no longer exclusively a television product, and are now produced for internet channels such as YouTube (Veríssimo, 2021b).

It should be noted that, during the pandemic and the resulting lockdown, media consumption was especially high. Examples of this were the use of videoconferencing services, video streaming, live broadcasts and free online videos (Cardoso & Baldi, 2020a, 2020b). As a result, video maintained its lead as the format most used by brands and that which most captures the attention of internet users. This trend is mirrored in one of the fastest-growing social networks in 2020, namely TikTok. Moreover, the speed and creativity of this type of content has had such an impact that Instagram has launched a similar new feature: Reels (FLAG, 2021).

4. The 21 Characteristics of Contemporary Advertising Communication

Since virtuality (1) and visuality (2) are two of the main characteristics of contemporary advertising discourse, as seen above, let us take a look at the other 19, which are equally interconnected (Santos, 2021):

3. Adaptability: audiences tend to be less and less captive and more “nomadic”/“agnostic”. We are faced with public opinion which is demanding, global, heterogeneous, dispersed, vigilant, reluctant and eclectic, within a context that is provisional and circumstantial. Therefore, organisations are “living organisms” that are constantly changing and must learn and relearn by continually making adjustments. Cross-cutting and transdisciplinary approaches are needed in the face of today’s complexity (Leal, 2017; Mesquita et al., 2020; Senge, 2009, as cited in Martins et al., 2020; Pereira, 2022; Scrofernenker & Oliveira, 2018): “this process is ongoing and communication matters fully intersect with it” (Martins et al., 2020, p. 331).

4. Immediacy: the speed with which messages are disseminated is important,and this is why the digital space requires increasing speed and agility. Virtual platforms make it possible to idealise and execute ideas more quickly and autonomously, and to measure the results of communication actions “in real time”. Immediacy is inescapable. The internet is a public space where interaction is uninterrupted and continuous: “in the digital environment, the market ‘never sleeps’” (Leal, 2017, p. 18). Given the greater intensity with which the message is propagated, this presupposes agility, dynamism, flexibility, availability and openness in responding to public opinion that is increasingly more attentive and interventional in the communication processes of brands (Costa, 2020; Leal, 2017; Magalhães & Marôpo, 2016; Martins et al., 2020; Scrofernenker & Oliveira, 2018).

5. Creativity: there are flows in the current era that more urgently requirea creative approach, in which internet users are more than ever the target of countless commercial messages, given the ubiquity of communication: “the more turbulent the medium, the more important the capacity for innovation” (Nobre, 2011, p. 64). As a result, our brain receives constant and varied stimuli, collecting and filtering countless pieces of information, and therefore becomes an increasingly closed and protective system - which is why attention is increasingly finite and diffuse, where a superficial reading of content predominates. Indeed, it is increasingly challenging to stand out in an effective and creative way in the current context, and it is markedly difficult to gain visibility “in the midst of a particularly crowded, tumultuous, competitive and rapidly changing communications market” (Volli, 2003/2004, p. 23). Thus, the creative dimension can help to obtain differential value in relation to the competition (Costa, 2020; Lindstrom, 2008/2009; Morais & Almeida, 2015; Summo et al., 2016; Volli, 2003/2004).

6. Ephemerality: ephemeral content is proliferating, such as stories, a growingformat on Facebook and Instagram. The concept is that photos, videos or messages can be made available for a short period of time and live broadcasts can also be made, in an unrepeatable matrix. The fear of missing out contributes to the success of this trend, which pushes internet users to be more present in order to have access to the experiences available. On the other hand, the joy of missing out (Costa, 2020; Martins et al., 2020) is in short supply.

7. Specificity: use of an inherent language - a new way of writing, in whichabbreviations, symbols, emojis and hashtags prevail (Leal, 2017; Mesquita et al., 2020; Veríssimo, 2021a).

8. Inclusivity: with a more participatory model in place, given the possibility ofaudiences becoming part of the content production process, brands no longer control what is publicised. They are no longer the only sources of information and are therefore more exposed when online, given the loss of control over the data disseminated. There may be an identity vulnerability at stake, since the reputation, credibility and trust of brands have become more fragile (Ferreira, 2018; Kotler et al., 2016/2017; Martins et al., 2020; Mesquita et al., 2020; Pereira, 2022; Scrofernenker & Oliveira, 2018; Silva et al., 2020).

9. Individuality: personalised, close and individualised content is created, inother words, content that meets the audience’s expectations, since messages that relate to the experiences and contexts of internet users stand out more easily, promoting emotional bonds, which can be leveraged by developing appeals that focus on emotion (Balonas, 2019; Coimbra, 2020; Ferreira, 2018; Kotler et al., 2016/2017; Martins et al., 2020; Mateus, 2020; Pereira, 2022).

10. Intentionality: the focus is on monitoring and managing content. Theprestige of a company, the visibility of a profile and the quality of a service are fundamental when it comes to creating added value to the offer in the technological world (Martins et al., 2020; Pereira, 2022; Scrofernenker & Oliveira, 2018; Silva et al., 2020): “the brand cannot be a mere label” (Dias & Baptista, 2019, p. 207).

11. Interactivity: while web 1.0 was associated with cognition, web 2.0 wasattributed communication and web 3.0 co-operation. Interactivity is the key element that distinguishes digital from analogue communication. It is necessary to interact with audiences, strengthening an emotional bond by exploring and stimulating connections, turning a customer into a brand ambassador (Escalada, 2018; Ferreira, 2018; Kotler et al., 2016/2017). Advocacy is at stake, with users becoming loyal defenders of brands. In the age of connectivity, loyalty is defined as the willingness to defend a brand. However, most loyal consumers are clumsy and passive, so the company’ job is to stimulate them in order to achieve supreme sales power (Kotler et al., 2016/2017): “an army of lovers willing to protect the brand in the digital world” (p. 53). To do this, it is necessary to increase the involvement of individuals. Institutions must therefore use creativity to improve their interactions with users, increasing their level of satisfaction, experience and engagement, in order to strategically create that “WOW” factor (Kotler et al., 2016/2017), which is: “an expression that a customer utters when they appreciate something that leaves them speechless” (p. 203).

12. Durability: ease of replicating and sharing content, which is available on theweb and easily found (Guedes et al., 2014; Magalhães & Marôpo, 2016): “the ability to disseminate the same texts, images and sounds to millions of citizens has become as essential as the ability to keep track of their birth, employment or health records” (Ferreira, 2018, p. 39).

13. Weighting: the presence of brands in the virtual arena represents the difference between competitiveness and success or decadence and pre-announced bankruptcy. However, many authors warn as regards the extent to which the strategy to be followed should play a leading role, thereby polarising the consequences of assertive or erroneous decisions, placing them respectively between “medicine” and “poison”. We therefore need to manage such a process with prudence and caution, aware that mistakes could have catastrophic repercussions in an open and pluralistic space. It should not be forgotten that this is potentially toxic territory, where latent aggression abounds, based on experiences and emotions rather than facts and arguments (Gurevitch et al., as cited in Ferreira, 2018; Martins et al., 2020; Remondes et al., 2016, as cited in Leal, 2017; Ribeiro & Assunção, 2022).

14. Quantity: one of the main advantages of digital communication is that itmakes it possible to measure the results of actions taken more effectively and thus understand what works, when considering the objectives established. This is based on mapping and quantifying, in particular: notifications, views, hashtags, likes, shares, comments, followers (and the degree of connection established with the accounts followed), mentions, interactions, clicks and other metrics. The algorithm and the way it is operationalised mirrors this goal: “likes or emojis force the algorithms to display the ‘most viewed’, the ‘most commented’ or the most ‘shared’” (Costa, 2020, p. 81). In the era of “screenogeny” (distinct from photogeny), what stands out is a numerical perspective, which is measurable through the results obtained. In fact, the digital format is linked to the logic of databases (Costa, 2020; Ferreira, 2018; Leal, 2017; Magalhães & Marôpo, 2016; Martins et al., 2020).

15. Relatability: actions must add value by creating a close bond with users, promoting engagement through constant stimulation. With the relatable paradigm in place, the aim is to establish links and connections with the public, based on the immaterial condition of the brand - in other words, to explore its symbolic dimension. This transforms “mundane interactions into evolving relationships” (Dias & Baptista, 2019, p. 217). To achieve this, it is important to provide unique, differentiated, relevant and striking experiences. The emphasis has shifted to the process (the relationship), which is more crucial than the end result (the sale). There have been other changes in the approach to the consumer: from the tangibility of the product, to the immateriality of the service and now to the experiential memory. Indeed, the home and the mobile phone are emerging as the new epicentres of experiences. The physicality is replaced by the respective virtuality, on a reduced stage: at home (homification; Dias & Baptista, 2019; Escalada, 2018; Kotler et al., 2016/2017; Martins et al., 2020).

16. Profitability: online media are associated with lower investments, that is,lower costs, compared to traditional media (Kotler et al., 2016/2017; Leal, 2017; Martins et al., 2020): “digital activation campaigns ( ... ) are generally cheaper” (Leal, 2017, p. 37), particularly “through search engines, social networks and email” (p. 18).

17. Responsibility: a particularly humanised, humanising and empathetic discourse is valued. Consumers are increasingly demanding responsible organisational behaviour, ethical conduct and activities that are conscious of and consistent with social and environmental practices. Social responsibility commitments are essential for building the reputations of companies (social branding; Balonas, 2019; Coimbra, 2020; Dias & Baptista, 2019; Pereira, 2022; Silva et al., 2020).

18. Simultaneity: brands are present on several platforms as part of a synchronousstrategy. Users also access the virtual universe through several screens simultaneously. The existence of multiple online stages presupposes their harmonisation, a task that involves a synergistic effort to ensure coherence with the company’s identity, alignment with its global strategy and respect for its communication policy. This is about achieving communicational stability through the prevalence of a common code. Although adaptable, given the specific nature of each social network, the aim is to unify the different approaches. Integrated communication should enable the fulfilment of both the mission and the organisational objectives

(Escalada, 2018; Guedes et al., 2014; Martins et al., 2020; Mesquita et al., 2020).

19. Sincerity: transparent and rigorous attitudes are favoured, since there isgrowing scrutiny from a more attentive, activist, participative and informed public: “following cyber freedom, nothing escapes the audience” (Oliveira & Ferreira, 2018, pp. 69-70). It is important to promote the reconciliation of storytelling (what is advertised) with storydoing (what is practised): “the identity of a brand that is structured on certain values will have to be worked on to maintain coherence between what it advertises and what it actually practises” (Dias & Baptista, 2019, p. 215). This is why the online environment emphasises the need for honesty and authenticity in brand communication (Balonas, 2019; Dias & Baptista, 2019; Leal, 2017).

20. Ubiquity: there is a requirement for regular communication. Absence orinconstancy in the virtual space can be damaging, and it is better to focus on more organic, regular monitoring of the consumer. From another perspective, we are witnessing the merging of public and private spaces, such as in sharing photographs or videos, which was previously done within a purely intimate context; and the obliteration of space and time: there are no physical or time barriers (Andrade, 2013; Arruda, 2016; Ferreira, 2018; Guedes et al., 2014; Pereira, 2022): “it is a truism to say that there has never been such omnipresence of technology in people’s lives as there is today” (Ferreira, 2018, p. 105).

21. Visibility: the digital arena is a highly competitive environment, made up ofvarious stimuli. It is becoming imperative to stand out, particularly with the spread of non-intrusive communication. Faced with this vicissitude, attention is being given to the implementation of strategies to capture and dominate attention, which brands see, when achieved, as a trophy (Costa, 2020; Guedes et al., 2014; Martins et al., 2020): “digital companies ( ... ) have developed various types of ‘seduction’ of the gaze” (Costa, 2020, p. 77), “transforming the gaze of actors into merchandise” (p. 88) so that the individual “is permanently ‘watching the screen’, which is stealing their attention” (p. 77).

5. Concluding Thoughts

Contemporary advertising communication has multiple facets, mostly based on its particularly digital nature. In fact, virtuality is an integral part of brand strategies, since being absent from the ubiquity of this universe could entail a number of communication risks for companies, as it would mean excluding them from a unique space, particularly for establishing dialogues with their audiences, and without this interaction, it would be difficult to establish connections. Several changes are implicit in the shift from the offline to the online paradigm, in particular the supremacy of two aspects, which end up characterising contemporary advertising: the emergence of the prosumer, through a participatory ecosystem in which the internet user simultaneously plays the roles of consumer and content producer; and the emphasis on the visual culture of messages, given their particular symbolic and emotional source. This specificity has positive repercussions on consumer processes, due to its wide-ranging ability to influence, i.e. the message from the images of advertising discourse has a greater impact than the textual aspect, and is therefore potentially more influential in purchasing dynamics, which is something that brands want. When focusing on the aesthetic component, video stands out.

These are changes that have brought significant challenges for advertising and all those involved in it, requiring a positive adaptation to the new communication flows and the emerging market demands that guide and mark this incomprehensible era. Based on the various readings carried out of different typologies and numerous national and international authors (duly identified throughout the article) in this bibliographical review exercise, the article identified the 21 main characteristics of advertising communication in the 21st century: adaptability, immediacy, creativity, ephemerality, specificity, inclusivity, individuality, intentionality, interactivity, durability, weighting, quantity, relatability, profitability, responsibility, simultaneity, sincerity, ubiquity, virtuality, visibility and visuality. It is hoped that this reflection can contribute in some way to a holistic understanding of the problem, given this summary of the most significant communicational properties of contemporary advertising. It could serve as clues for future empirical or conceptual research, given the breadth of the conclusions drawn. Even so, this is theoretical research, so one of the limitations inherent to this could be the lack of practical applicability able to validate the conclusions drawn in loco, as well as the strategic choice to focus on just two aspects, to the detriment of the other 19. Future studies could explore any of these many variables and even remove, add or replace other properties, given that this article reflects the fickleness of the present day, certainly fertile in terms of changes and sterile in terms of dogmas.

REFERENCES

Andrade, P. (2013). Ontologia sociológica da esfera pública digital: O caso da web 2.0/3.0. Comunicação e Sociedade, 23, 186-201. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.23(2013).1621 [ Links ]

Araújo, R., & Lopes, F. (2013). A construção de significação através da emoção. Comunicando, 2, 16-26. https://doi.org/10.58050/comunicando.v2i1.128 [ Links ]

Arruda, J. (2016). A fusão dos espaços públicos e privados no novo paradigma comunicacional. Sociologia On Line, 11, 42-63. [ Links ]

Autoridade Nacional de Comunicações. (2021). Relatório anual 2021 - Pandemia/COVID-19: Impacto na utilização dos serviços de comunicações. https://www.anacom.pt/streaming/Impacto_COVID19comunicacoes2021v20220324.pdf?contentId=1719172&field=ATTACHED_FILE [ Links ]

Balonas, S. (2019). Que a força esteja contigo - Os desafios da publicidade na nova galáxia comunicacional. Media & Jornalismo, 19(34), 13-34. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_34_2 [ Links ]

Baptista, D., & Estrela, S. (2019). Os desafios da comunicação digital nas PME. In A. Ferreira, C. Morais, M. F. Brasete, & R. L. Coimbra (Eds.), Pelos mares da língua portuguesa 4 (pp. 201-2017). UA Editora. http://hdl.handle.net/10773/27566 [ Links ]

Barroso, P. (2017). A imagem como ausência. Vista, (1), 50-71. https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.2970 [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Polity Press. [ Links ]

Berni, F., & Accorsi, F. (2019). O uso de imagens em produções publicitárias e suas implicações jurídicas, éticas e criativas. In XX Congresso de Ciências da Comunicação na Região Sul (pp. 1-15). Intercom - Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação. [ Links ]

Burnay, C., & Vicente, P. (2023). Estudos em audiovisual e multimédia. Comunicação Pública, 18(34), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.34629/cpublica.v18i34 [ Links ]

Cádima, F. (2019). A publicidade face aos novos contextos da era digital: Privacidade, transparência e disrupção. Media & Jornalismo , 19(34), 35-46. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_34_3 [ Links ]

Carapito, S. (2010). O estatuto da imagem na publicidade e o seu valor estratégico: Reposicionamento da marca Fundão [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade da Beira Interior]. uBibliorum. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.6/1269 [ Links ]

Cardoso, G. (2023). A comunicação da comunicação. As pessoas são a mensagem. Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

Cardoso, G., & Baldi, V. (Eds.). (2020a). Impacto do coronavírus e da crise pandémica no sistema mediático português e global. Observatório da Comunicação. https://obercom.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Covid19_impacto_final.pdf [ Links ]

Cardoso, G., & Baldi, V. (Eds.). (2020b). Pandemia e consumos mediáticos. Observatório da Comunicação. https://obercom.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Final_Pandemia_media_Geral.pdf [ Links ]

Cardoso, G., Paisana, M., & Pinto-Martinho, A. (2022). Digital news report Portugal 2022. OberCom. [ Links ]

Carrera, F. (2015). A habilidade social da marca: Uma reflexão sobre interação marca-indivíduo no ambiente digital. Tríade: Comunicação, Cultura e Mídia, 3(6), 91-107. https://periodicos.uniso.br/triade/article/view/2266 [ Links ]

Coimbra, R. (2020). Comportamento do consumidor, satisfação com a vida, dimensões culturais e motivação hedónica e utilitária: Um estudo nos supermercados do Brasil, Coreia do Sul e Portugal [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade do Porto]. Repositório Aberto. https://hdl.handle.net/10216/128469 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R. (2020). Impactos da captologia: Problemáticas, desafios e algumas consequências do “dar vistas” ao ecrã em rede. Sociologia On Line, 23, 74-94. https://doi.org/10.30553/sociologiaonline.2020.23.4 [ Links ]

Costa, P. R., & Martins, M. de L. (2023). As leis da captura da atenção. Reflexões em torno do vídeo nas plataformas digitais. Vista, (11), e023002. https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.4512 [ Links ]

Dias, C., & Baptista, A. (2019). A imaterialização da marca: Da economia da mercadoria à economia da transformação. Comunicação, Mídia, Consumo, 16(46), 205-225. https://doi.org/10.18568/cmc.v16i46.1878 [ Links ]

Escalada, S. (2018). Gestión de marca y adaptación paradigmática del impacto masivo a las conexiones transmedia. In M. Navarro, M. Patiño, & I. Alemán (Eds.), Comunicación corporativa en red (pp. 125-141). Ediciones Egregius. [ Links ]

Ferreira, G. (2018). Sociologia dos novos media. LabCom.IFP. [ Links ]

Ferreira, I. (2019). Incursão pelos modelos de análise da imagem publicitária. Media & Jornalismo, 19(34), 115-126. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_34_8 [ Links ]

Ferreira, I., Prior, H., & Bogalheiro, M. (2008). Em defesa de uma retórica da imagem. Rhêtorikê, (0), 1-13. [ Links ]

FLAG. (2021). Tendências de marketing para 2021. FLAG. [ Links ]

Galhardi, L. (2019). A imagem-comoção publicitáriano audiovisual da web [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos]. [ Links ]

Guedes, E., Silva, M., & Santos, P. (2014). Esforços comunicacionais para a construção de relacionamentos na contemporaneidade: Mediações e tecnologia. Comunicação e Sociedade, 26, 223-233. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.26(2014).2035 [ Links ]

Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2017). Marketing 4.0.: Mudança do tradicional para o digital (P. E. Duarte, Trad.). Actual Editora. (Trabalho original publicado em 2016) [ Links ]

Lapa, T., & Vieira, J. (2019). Divisões digitais em Portugal e na Europa: Portugal ainda à procura do comboio europeu? Sociologia On Line, 21, 62-82. https://doi.org/10.30553/sociologiaonline.2019.21.3 [ Links ]

Leal, B. (2017). A marca - Comunicação e ativação digital [Dissertação de mestrado, Instituto Politécnico do Porto]. Repositório P.Porto. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.22/11191 [ Links ]

Lima, T. (2013). A imagem publicitária de alimentos e sua importância no consumo [Monografia de bacharel, Universidade Católica de Brasília]. Repositório Institucional da UCB. [ Links ]

Lindstrom, M. (2009). Buyology: A ciência do neuromarketing (D. S. Tavares, Trad.). Gestão Plus. (Trabalho original publicado em 2008) [ Links ]

Lopes, M. (2015). A importância da publicidade emocional no marketing viral [Dissertação de mestrado, Instituto Politécnico de Viseu]. Repositório Científico do Instituto Politécnico de Viseu. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.19/3120 [ Links ]

Magalhães, M., & Marôpo, L. (2016). Investigação em comunicação digital: Uma reflexão sobre métodos para a análise de redes sociais. Comunicando, 5(1), 86-103. [ Links ]

Martins, C., Ruão, T., & Melo, A. (2020). Política de comunicação: Veneno ou remédio? Um olhar sob a perspetiva da comunicação organizacional. In Z. Pinto-Coelho , T. Ruão, & S. Marinho (Eds.), Dinâmicas comunicativas e transformações sociais. Atas das VII Jornadas Doutorais em Comunicação& Estudos Culturais (pp. 328-349). CECS. [ Links ]

Mateus, S. (2016). Possibilidades argumentativas da imagem publicitária. Publicitas, 3(2), 27-36. https://www.revistas.usach.cl/ojs/index.php/publicitas/article/view/2385 [ Links ]

Mateus, S. (2020). Retórica afetiva. Subsídios para a compreensão da natureza do pathos. Sopcom. [ Links ]

Mesquita, K., Ruão, T., & Andrade, J. (2020). Transformações da comunicação organizacional: Novas práticas e desafios nas mídias sociais. In Z. Pinto-Coelho, T. Ruão, & S. Marinho (Eds.), Dinâmicas comunicativas e transformações sociais. Atas das VII Jornadas Doutorais em Comunicação & Estudos Culturais (pp. 281-303). CECS. [ Links ]

Morais, M., & Almeida, L. (2015). Perceções de obstáculos à criatividade em universitários de diferentes áreas curriculares e níveis de graduação. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 2(2), 54-61. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2015.2.2.1358 [ Links ]

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Eddy, K., & Nielsen, R. K. (2022). Reuters Institute digital news report 2022. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [ Links ]

Nobre, A. (2011). Práticas e discursos estratégicos - Da norma à transgressão, da rotina à inovação. In A. Palácios & P. Serra (Eds.), Pragmática: Comunicação publicitária e marketing (pp. 63-83). LabCom Books. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. (2018). A construção social do eu através da experiência nas redes sociais - Hipermodernidade, leveza e adolescência. Comunicando, 7(1), 61-87. https://doi.org/10.58050/comunicando.v7i1.185 [ Links ]

Oliveira, J., & Ferreira, I. (2018). Quanto o texto publicitário se transforma em meme. Rhêtorikê, (5), 55-71. [ Links ]

Pereira, I. (2022). Perspetivas estratégicas para a comunicação empresarial nas redes sociais: Complexidade das dinâmicas relacionais entre empresas e consumidores [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Nova de Lisboa]. run. http://hdl.handle.net/10362/143525 [ Links ]

Petermann, J. (2006). Imagens na publicidade: Significações e persuasão. UNIrevista, 3(1), 1-8. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, F., & Assunção, C. (2022). Medir a qualidade dos comentários online: Uma proposta metodológica a partir de sites jornalísticos em Portugal, Brasil e Espanha. Signo y Pensamiento, 41, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.syp41.mqco [ Links ]

Ribeiro, S. (2020). A comunicação digital das PME com o aparecimento da pandemia de COVID-19, em Portugal [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Europeia]. Repositório Comum. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/38781 [ Links ]

Salbego, J. (2007). A composição da imagem no anúncio publicitário. In VIII Congresso de Ciências da Comunicação na Região Sul (pp. 1-13). Intercom - Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação. [ Links ]

Santos, C. (2013). Publicidade e identidade: Que relação? Comunicação Pública, 8(14), 37-55. https://doi.org/10.4000/cp.567 [ Links ]

Santos, C. (2019). A influência publicitária no consumo de marcas de vestuário e de calçado em contexto juvenil. Media & Jornalismo, 19(34), 221-238. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_34_16 [ Links ]

Santos, C. (2021). No trilho da comunicação do século XXI: Tendências e desafios. In J. Pinto (Ed.), Audiovisual e indústrias criativas: Presente e futuro (pp. 835-849). McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Santos, C. (2022). A criatividade no ensino superior: Um estudo exploratório sobre as licenciaturas em publicidade. Comunicação Pública, 17(32), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.34629/cpublica.358 [ Links ]

Saturnino, R. (2020). Novas formas de performance social no contexto digital da “economia da partilha”. Estudos em Comunicação, (31), 191-213. https://doi.org/10.25768/20.04.03.31.09 [ Links ]

Scafura, B. (2020). Assista-me jogar: Uma reflexão sobre o impacto da pandemia de COVID-19 no consumo e produção de conteúdo em plataformas de live streaming. Comunicando, 9(1), 152-171. https://doi.org/10.58050/comunicando.v9i1.63 [ Links ]

Scrofernenker, C., & Oliveira, R. (2018). Comunicação estratégica: (Im)precisões conceituais e dimensões possíveis no contexto das organizações. Media & Jornalismo, 18(33), 103-113. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_33_7 [ Links ]

Silva, S., Ruão, T., & Gonçalves, G. (2020). O estado de arte da comunicação organizacional: As tendências do século XXI. Observatorio (OBS*), 14(4), 98-118. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS14420201652 [ Links ]

Simões, M., & Augusto, F. (2019). Expostos e duplamente vigiados: O caso do Facebook. Análise Social, 230(1),132-153. https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2019230.06 [ Links ]

Sousa, V., Costa, P. R., Capoano, E., & Paganotti, I. (2020). Riscos, dilemas e oportunidades: Atuação jornalística em tempos de COVID-19. Estudos em Comunicação, (31), 1-33. https://ojs.labcom-ifp.ubi.pt/index.php/ec/article/view/881 [ Links ]

Steagall, M. (2020). Imagens conceituais na publicidade: Premissas da imagem publicitária potenciadas pela tecnologia e interatividade. Convergências, XIII(26), 53-62. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.11/7473 [ Links ]

Summo, V., Stéphani, V., & Téllez-Méndez, B.-A. (2016). Creatividad: Eje de la educación del siglo XXI. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, vii(18), 83-98. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2016.18.177 [ Links ]

Toffler, A. (1984). A terceira vaga (F. P. Rodrigues, Trad.). Livros do Brasil. (Trabalho original publicado em 1980) [ Links ]

Veríssimo, J. (2021a). A publicidade e os cânones retóricos: Da estratégia à criatividade. Labcom. [ Links ]

Veríssimo, J. (2021b). Retórica clássica e storytelling na práxis publicitária. Comunicação e Sociedade, 40, 207-223. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.40(2021).3514 [ Links ]

Volli, U. (2004). Semiótica da publicidade (M. L. Jacquinet, Trad.). Edições 70. (Trabalho original publicado em 2003) [ Links ]

1Despite such unavoidable digital primacy, there is an underlying commitment to a hybrid strategy, combining online and offline media within a complementary matrix (Balonas, 2019; Leal, 2017).

2Prosumption reflects a substantial transformation of ingrained values, allocated to a third wave, the origin of which lies in the miscegenation of its predecessors - if in the first wave an agricultural society prevailed, based on production for use, in the second wave production for exchange proliferated, as a consequence of an industrial society (Toffler, 1980/1984).

Received: July 12, 2023; Revised: August 03, 2023; Accepted: August 14, 2023

texto em

texto em