Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versão On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.12 Braga dez. 2023 Epub 30-Jan-2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.4671

Varia

Stories of Life and Lives of History. Testimony and Fiction in Photography Regarding a Project

1 Labcom, Faculdade de Artes e Letras, Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal

Neste ensaio apresento um trabalho da minha autoria, concebido e produzido em 2022, caracterizado por uma exposição fotográfica e por um livro: Linhas com Cruzamentos de Destino (photobook; Câmara Municipal de Palmela; Camilo, 2023). A seguir, proporei uma reflexão sobre como nele se cruzam dimensões incontornáveis em qualquer registo fotográfico: a da realidade histórica e a da representação, que é uma realidade simbólica, ficcional. Na última parte, discriminarei os aspetos dos contextos de produção e de receção que subjazem este projeto. Na reflexão apresentarei fotografias quer do projeto, quer da história da fotografia que considero relevantes. Do ponto de vista epistemológico, embora o ensaio incida na implementação de um projeto, nele se cruzam referências inscritas do domínio da história da fotografia, da antropologia visual e da semiótica.

Palavras-chave: projeto fotográfico; teoria da fotografia; teoria da imagem; antropologia; semiótica

In this essay I will present a work of mine, conceived and produced in 2022, which consisted of a photographic exhibition and a book: Linhas com Cruzamentos de Destino (Lines With Destination Crossings; photobook; Câmara Municipal de Palmela; Camilo, 2023). Following this, I will reflect on how this cuts across aspects that are unavoidable in any photographic record, namely that of historical reality and that of representation, which is a symbolic, fictional reality. In the last section, I will outline the production aspects and reception contexts that underlie this project. In this reflection, I will present relevant photographs of the project and the history of photography. From an epistemological point of view, although the essay focuses on the implementation of a project, it weaves in references from the history of photography, visual anthropology and semiotics.

Keywords: photographic project; photography theory; theory of image; anthropology; semiotics

1. Part I

In 2022, I attended a series of visits by railway workers from Comboios de Portugal (CP) to the museum - A Estação (The Station) -, located in the town of Pinhal Novo, in the municipality of Palmela, as part of the “In My Time...” initiative. This was a cultural activity complementing the museum’s existing collections. Seeing as the museum has a remarkable collection related to the railway world, a series of talks was organised in which retired CP workers spoke about their life stories as railway workers, thus helping to contextualise some of the equipment, utensils and uniforms on display. My aim with this project was to join the stories told during the visits, as well as those from a series of interviews I conducted, with the implementation of a proposal to create a series of photographic portraits. This proposal, which was approved and subsidised by Palmela Town Council, to be produced that year and implemented in the following (2023), included two features: an exhibition of photographic portraits and a book - Linhas com Cruzamentos de Destino (Lines With Destination Crossings; photobook; Câmara Municipal de Palmela; Camilo, 2023) - which would combine these portraits with short texts summarising the statements made by those workers, both during the initiatives carried out by the museum and in the interviews I conducted.

The exhibition took place in 2023, between 1 and 26 February, at the Pinhal Novo Municipal Auditorium - Rui Guerreiro, and consisted of the exhibition of 15 portraits, complemented by a landscape of the Pinhal Novo railway station. It was also at the opening of the exhibition that the photobook was launched. A 50-page book of photographs and texts, made up of 15 additional portraits - originals which were not included in the exhibition - combined with short stories evoking the professional life of each railway worker. All this material was complemented with photographs from a personal collection taken during train journeys between Lisbon and Covilhã, chosen carefully so that the route was not obvious. I wanted those images to be exclusively evocative of this railway reality.

1.1. History and Fiction: The Underlying Dimensions

Although this project, made up of an exhibition and a book, is syncretic (if by this is meant the reconciliation of different forms of expression, as happened with the photographic image, the text, and even the exhibition space, which is significant for the ways of discovering the images), two intersecting realities that also characterise the ontology of any photographic image also exist within it: historical reality (which I consider to be closely related to the “life stories”) and symbolic reality (that of meaning, that of discourse - referring to the “lives of history”). I will begin their characterisation by firstly formulating three ideas: these realities are “real” in terms of their narrative particularities; they have an interdependent status; and I am refraining from making any value judgements about them.

1.1.1. Life Stories

From an epistemological point of view, it is in the area of life stories that the object of study for historians, sociologists and anthropologists is revealed. Faced with the past or the present, they try to study a society or a culture as comprehensively and objectively as possible.

As far as this project is concerned, this analytical plan can be viewed in two ways. Firstly, it refers to the lives of the ex-railway workers, their families, their careers at CP, their values, among other aspects, which, in some ways, were reported in the “In My Time...” initiative. This is the dimension that most interests a historian or anthropologist/sociologist looking to reconstruct personal and corporate identities and cultures. The second way of looking at this plan for analysing life stories does not focus on the study of retired CP railway workers, but on the context and circumstances underlying both the “In My Time...” initiatives and the creation of a project that included the production of a photography exhibition and the publication of a photobook.

The “stories” no longer focus on the professional lives of the ex-railway workers, but on those of the photographer, in relation to my decisions, production standards, aesthetic influences, editorials, and so on. Which relationships were established between myself and the museum in terms of expectations and requirements (not least because this project received support for mounting the exhibition and publishing the book)? Why did I opt for this type of portrait, so centred on medium shots and a frontal pose? What is the reason behind the layout, the short story text genre, the selection of the exhibition venue and the exhibition period? Why was the photographic record so studio-based? Was this the most appropriate way to satisfy the expectations and objectives of the parties involved in the project (the museum, myself and the railway workers photographed and interviewed)? This entire issue would require an analytical detour, through discovering other lives and other stories - those of the protagonists behind the mounting of an exhibition and a book - but which are not now within the scope of this essay.

Whether from a point of view centred on the ex-railway workers or on the subjects who produced the communication “artefacts”, this is where the world of life is inscribed - constantly changing, multidimensional - the fragment of which - in space and time - the photographic image records, becoming (from a semiotic point of view) its documentary trace. It is these fragments that make up the photographs: moments fixed on a surface that is more or less sensitive to light, referring to a space and time of action (the geographical space and the historical moment of the recording), but also spatialised and timed based on a mechanical representation device, a frame and a shutter “speed”.

I will thus focus on some of the specific contextual aspects of producing this project. As I mentioned, the subject of the project was the representation of retired CP railway workers in studio portrait photographs (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4), exhibited and published in a photobook.

The expectations were essentially of a communicational nature: I wanted to produce images and write meaningful life stories, testimonies that would evoke a professional career, and even a certain level of subjectivity. On the other hand, the museum’s main concern was the need to faithfully record the testimonies created through the “In My Time...” initiatives. In terms of relations with ex-railway workers, there were other expectations, especially with regard to how they wished to be “well portrayed”. Sometimes it was necessary to explain that what was being photographically staged or reported established a figurative (connotative) relationship consisting of evocation, requiring a reading and gaze that could be neither literal nor direct. I will return to this when I reflect on the veridiction modalities and the veridiction contract that guided this project.

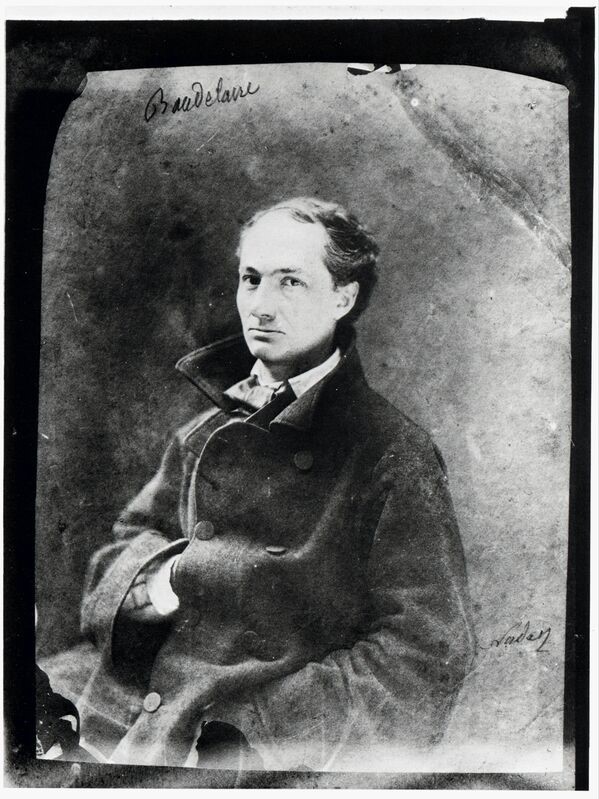

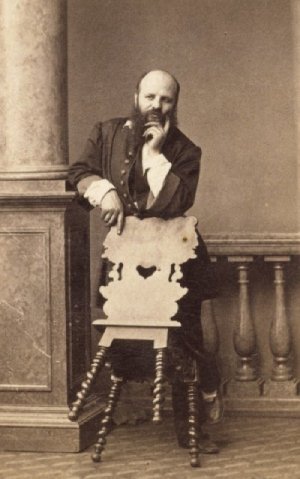

It is understandable that the disparities existent in the conceptions of producing a portrait - those of the photographer and the photographed - are the result of a somewhat assumed recognition of the potential of photography in the construction of an ethos. This is a peculiarity that is not new. It already existed in the early days of photography, and was felt and managed by studio portrait photographers such as Félix Nadar (1820-1910) or André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (1819-1890), when managing/staging the poses and circumspect physiognomies of the bourgeois in portraits as significant resources evocative of integrity and honour. In this respect, I cannot deny that the collection of portraits produced is characterised by a certain composition, requiring the mobilisation of certain objects and uniforms, even a pet (a cat), and the recurring staging of a 3/4 pose (neither fully frontal nor in profile). They are significant resources serving the same evocative purpose as the props of those old photographic studios. The difference lies in the intentionality behind all these expressive recurrences: the evocation of an identity, of an ethos that is not only subjective (as was the case with the bourgeois portrait or the carte-de-visite of the bonhomme portrait), but which is primarily intended to be corporate: women and men whose identities were forged on the railway and at CP.

I would emphasise that this evocation of a corporate ethos did not stem exclusively from the photographic record. It should be recalled that the project is syncretic

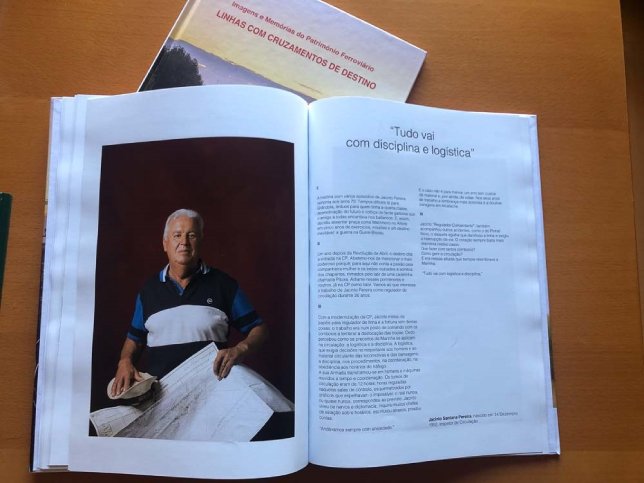

- nourished by both images and words. It was an exhibition and a photobook. Therefore, the evocations I wanted to elicit also resulted from a complementary relationship between images and words, which was evident from the way the book was laid out. On one sheet, odd-numbered pages, there was the photograph, and on the other, the text along with its heading. The images play out a fundamental meaning in the text or heading, sometimes illustrating it (“The Tickets Are Cardboard and Paper” - Rafael Rebola Rodrigues; Figure 4), at other times subtly evoking it by metonymy (“Do You Know What Drives a Train?” - Henri Alcaçorenho da Silva; Figure 5) or by metaphor (“Story of a ‘Cat’ and Her Flag” - Madalena Nobre Rodrigues João; Figure 6). Sometimes the opposite happens: it is the text that imposes meaning on the image (“Memories of a Boy Who Was Easter Lamb” - José António Galhofas Carvoeira; Figure 7).

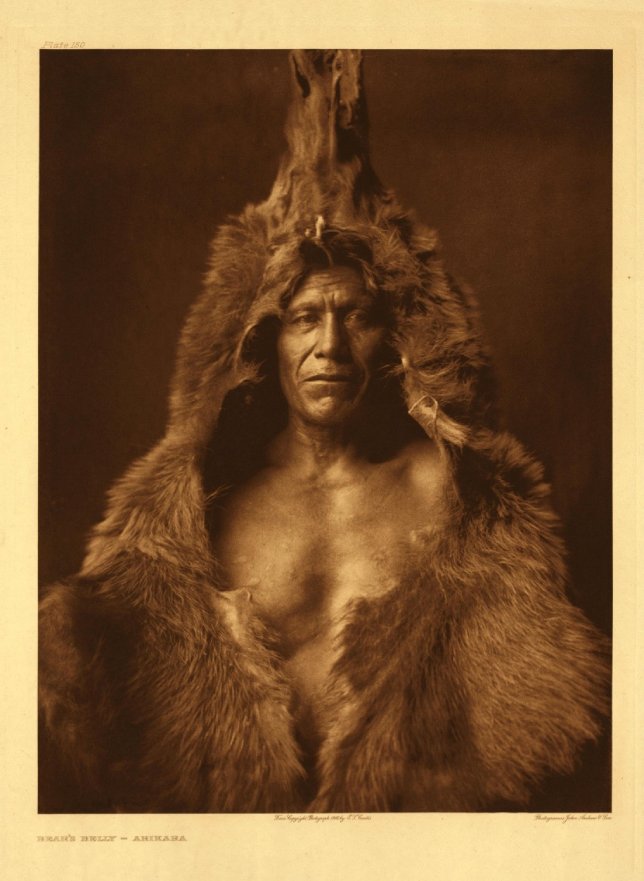

I have already mentioned that this photographic and editorial project complemented the museum’s “In My Time...” initiatives. I was present during the visits when the testimonies were taken, trying to record key ideas. I sometimes also found myself having to carry out additional interviews. The aim was to write short texts - in the form of short narratives, chronicles with a beginning, middle and end (in the form of a denouement) - that evoked the careers or exemplary aspects of these individuals’ professional lives. In short, as part of a project where the image played an important role, the word, especially the spoken and heard word, was indispensable. It was by reference to the words that the portraits were produced, but these also induced a reading so that they could be interpreted. Without this symbiotic relationship, the photographs risked being seen as representations of an anthropometric presence, like those of My Portman on the Uchick tribe (1890; Andrade, 2002, pp. 56-57) or as an “exotic curiosity”. With the combination of text, the aim was for them to be able to evoke a (corporate) identity rather than signify an identification. This is why it is argued that this work is in line with the portraits developed by Edward Curtis (Figure 8), setting out “the history of all the Indian tribes, their life, their ceremonies, their legends and myths” (Adam, 2001/2008, p. 32). Like this artistic photographer, I have adopted the role played by the staging, the (ostensibly studio) composition, the choice of props (but also the role played by words in evoking this corporate identity), regardless of recognising the disparity of the contexts, objectives and natures underlying these projects.

In short, I did not want to view these images as mere records - which, from a scientific point of view, are always difficult to utilise due to the continuous specificity of any image and the subjectivism of interpretation. On this subject, see Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead’s (1942) position on the potential of using photography to understand the culture and character of the Balinese: it is an excellent way of recording and understanding (for example, see the work of Fabiana Domingues Sanches, 2017), but which contrasts with the difficulties of interpretation and the lack of methodologies for iconographic analysis. Instead, I preferred to look at them in a similar way to visual anthropology, where photography - in this case complemented by text - refers to abstract and formal content, related to ideology, culture, social organisation and politics (Sanches, 2017, p. 73), which, from a semiotic point of view, will always need to call on a connotative analysis. In the case of my project, photographs are understood as evocative signifiers of corporate life stories; as signifiers that establish a complementary relationship with the spoken and written words of the interviewees, in a personal process of discovery. I recognise the seminal nature of these considerations, which require further study in the field of visual anthropology and photography, which will have to be undertaken in future reflections. I must remind the reader, however, that the epistemological background used for this reflection comes mainly from the more classical literature of semiology and semiotics - Charles Peirce, Roland Barthes, Georges Péninou, Jean-Marie Floch, Martine Joly, Philippe Dubois and, necessarily so, Algirdas Greimas - from whom I have taken my position on this issue.

1.1.2. The Lives of History

In the study of photography as a source of information, as a document - and there is no doubt about the status of photography as a document (Kossoy, 2012) - there are considerations to be formulated which arise from certain aspects of its semiotic specificity, that is, its status as a sign. Such formulation is significant because in the material aspects of photography as a sign, sometimes certain aspects intersect, giving rise to disparate forms of interpretation. These were also present in this project. I will now categorise them based on a number of considerations.

First consideration: what is in the photograph. In relation to the “life story”, from a semiotic point of view, photography is just an index of a moment, a “proof of contact”, a very interesting term that belongs to the lexicon of photographic praxis. This particular aspect meant that what was previously written about stories with life was reduced to a product involving a choice to select certain facts as part of a book and an exhibition, sponsored by the A Estação (The Station) museum in 2022, in a specific space where the portraits were taken (my photographic studio, located in the city of Barreiro) related to a cast (the participants, whose identity is easily recognisable in the photobook entries and in the exhibition captions). In terms of the photographic production itself, this choice can be stated even more precisely: what was framed in terms of the shot? How was it framed in terms of shutter speed (exposure time)? And here alone, I could go on forever laying bare increasingly varied aspects. It is as if in the project, and especially in the photographic record, choices took the form of cuts, spatial and temporal segmentations of these life stories, so that the part (the indicative record of these cuts) is not to be confused with the whole (the globality of the historical context to which the project refers). Any “historical moment” is inevitably transformed into a “symbolic moment”, at the same time as the world (of “life stories”) is transformed into a world of representation and meaning (of “lives of history”). Because it is indicative, from the perspective of its testimony to the fissure of a space and a time, photography is the mark of the emergence of a document. But it is also the mark of a choice - intentional or involuntary, conscious, or not - to have done so at that moment, in that place and to have chosen to emphasise certain moments and aspects over others.

And what is in these photos? The visual record of various instances of someone, who is identified and known on the basis of an account and verbal identification (name, date of birth, professional position). The historian can explore some interesting material in this corpus for their study of the world of railways, especially with regard to working props such as lanterns, flags, tickets, uniforms, pickaxes, train manuals, route sheets and uniform guidelines. The photograph (complemented by some kind of text) is the recording of data testimony, a field tool, an observation instrument. In addition, what is in the photographs are meanings indicating my decisions as a photographer, testimonies about the choices of assuming a viewpoint embodied in a frame (mainly medium shots), an angle (frontal, neither low nor high angle), a pose (mainly 3/4, sometimes frontal against a neutral backdrop characterised by a burgundy backcloth), the choice of a certain shutter speed (1/125), aperture (mainly f:8) and sensor sensitivity (ISO 100); in valuing a certain type of photography (exclusively digital and in colour), in managing the lighting (soft, using an octagonal softbox, sometimes with a kicker light at a contrast ratio of 2:1) and in minimal post-editing in Lightroom and Photoshop to standardise exposure and colour temperature. In short, these decisions reflect a personal style and an “ideological” vision of the subject, namely that of wanting to produce a standardised “collection of images” from which the prop or the pose of the photographed individual were the main elements signifying a personal and, above all, corporate identity (that of former CP railway workers). See, for example, Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 6 and Figure 7, presented above, and Figure 9 and Figure 10.

The technical options involved in standardising the photographic record were therefore an important element of expression in “bringing out” connoted meanings that evoked the ethos of the text, that stated subjectivity which results from an individual’s professional career. That is why this work has established correlations with certain references in the field of photography. Recognising the importance of portraiture as a photographic genre and the existence of indispensable references (such as, for example, August Sander in his portrait series, or an artist who has greatly influenced me - Yann Arthus-Bertrand), some of whom even form part of the music and fashion cultural industries (such as Annie Leibovitz or Helmut Newton); recognising the importance of photographers who reintroduced the world of work and workers, as was the case in Portugal with Eduardo Gageiro and Augusto Cabrita (1978). I would highlight the collection by Gilberto Gomes (1995), an RTP documentary produced by Cabrita (1978), on the history of trains in Portugal, as well as a few scattered images of railway workers in family catalogues. My influences in this project mainly relate to the aforementioned Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (Félix Nadar) and André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri. The latter was remarkable because he was not only a pioneer in the art of the studio portrait, but also in terms of the value he placed on the “staging” of the body (the gesture, the pose) and of the prop (scenery, object, clothing) as meaningful resources capable of going beyond the more obvious and denotative meanings stemming from the presence of the person portrayed, towards those referring to a spirituality and a personality, present in the domain he called “photogeny” (Frizot & Ducros, 1987, pp. 37-47; Figure 11 and Figure 12), but which, in the case of my work, I considered to be professionally specific (relating to the world of trains) and corporately specific (referring to CP).

This meaning is more evident in certain photographs, such as the portrait of Artur Dias Henriques (Figure 9), a ticket inspector; in others, the image needs the text for the viewer to understand the importance of an apron and a platter in the portrait of Eliseu Correia do Santos, a machinist (Figure 10).

The dichotomy between the significance of a presence, of identification, and the connotative significance, evocative of a (professional and corporate) identity, also stemmed from references and influences on the status of photography in anthropology, as I have already mentioned. It is true that in this photographic project the pose and the prop were the result of an assumed photographic staging, more significant within the context of a symbolic universe adjacent to art than to science. However, according to Rosane de Andrade (2002, p. 28), a supposedly positivist gaze with a strict objective record, without consideration for the expression of feelings or emotions, is insufficient in ethnographic photography. According to the author, science needs to be reconciled with art so that it can signify something more immaterial, something related to an axiology, a culture, which requires the involvement of the observer with the object of study, in short, participant observation. Moreover, she gives examples that support this argument: Pierre Verger, in fact Pierre Fatumbi Verger (1902-1996; Baptiste, 2009), a French photographer-anthropologist who is fundamental to our knowledge of Afro-Brazilian culture in Salvador de Bahia, endeavoured to complement a documentary approach with a significant artistic record, which possessed the characteristic spirituality of a cultural dimension.

In this inventory, I would also like to mention Claúdia Andujar’s work on the Yanomami indigenous people (Andrade, 2002, p. 62). Whilst it is true that her work is not studio-based (nor is Pierre Verger’s), the mention of this work stems from the complementary relationship that her images establish with words in order to evoke a spirituality, an objective that I tried to achieve in the photobook through the relationship between the photograph, the heading and text of the life stories, with the aim of evoking the subjective and corporate ethos mentioned above. These syncretisms, which had the aim of evoking those “fluid” connotative meanings, required a lot of tentative work, involving trial and error. It required knowledge and research about CP, working conditions, especially in the Barreiro workshops where they were trained, attentive listening to testimonies during the visits to the museum, in-depth interviews, writing up the testimonies in the form of short stories, discussion with the interviewees to verify data, reflecting with the museum staff when searching for props evocative of their careers, and a lot of time in the studio to take the photos, as well as selecting images. In this work, however, participant observation was not employed. The reason why can be understood: it is not centred on describing and analysing practices in use, but on describing memories.

Other particular aspects of the testimonies are also worth considering, and can be seen from the photographic record of each of the project’s photographs (those that make up the photobook and the exhibition) and from a “syntagmatic relationship” involving the sequential arrangement of the images and their relationship with the text and layout. The sequences, whether those resulting from the ordering of the images in the exhibition or the pagination in the book, are indicative of inevitable hierarchies, which reflected personal positions on the individuals photographed. Since I was the author of this project, I would like to make it clear that my concerns were of a communicational nature. The management of the collection of photographs was a testament to the desire to ensure the intelligibility of the meanings conveyed: in the case of the exhibition, the optimisation of the space, by arranging them in the foyer to make them easier to understand; as far as the photobook is concerned, their organisation throughout the pages was based on a thematic criterion relating to “CP trades”.

Second consideration: the staging of authenticity. I have been demonstrating how indispensable the testimonial aspect of the photography is due to its semiosic status as an index. Photography cannot exist as a document without being a “touch and go”, a record of the instant in which the moment and the movement of history were frozen by a personal choice on the part of the photographer.

However, photography also has other particularities that derive from its singularities as an icon and symbol and which cannot be ignored. It is testimony, but it is also fiction, arousing in the interpreter the conviction that the objects are being faithfully represented in the “highest definition” (interpretative). Curiously, this is one of the most contemporary meanings of photography, which does not necessarily correspond to the way it was received as a technological form in its early days. Photography is an icon, but not one of the most “complete” from the perspective of reliable reproduction, in the manner of a copy, of the various characteristics of the object. It is the product of the two-dimensional transformation of objects and their original black and white representation. The popular adoption of photography was due both to a fascination with the fidelity of the iconographic record (which surpassed the more accomplished pictorial realism) and to the specificity of the outputs of a technological mechanism that was revolutionary at the time - a mechanism for producing indices. The realistic “naturalisation” of photography as a representation gradually developed as this device became more popular, to the point where it was no longer received with strangeness and curiosity. It should be added that this naturalisation was also due to the technical capacity of the photographic camera to perpetuate ancestral and canonical forms of visual representation and understanding alongside a system of visual representation based on perspective and which had been in force since the Renaissance (Kossoy, 2021, p. 18).

The (iconic) specificity of the photographic record generates illusions akin to verisimilitude: rather than signifying the truth (resulting from the referential relationship of photography as a sign that always presupposes the existence of a referent), it is important to consider the strategies utilised to signify the verisimilitude of “authenticity”. In the project, from an expressive point of view, this series of portraits was intentionally staged to provide a veridictory element alongside the significance of a “presence”, preferably of a corporate nature (thus evoking “trades” and a “business reality” - that of CP). This meaning was ensured by utilising a repertoire of iconic signs that, in their articulation, signified a narrative, a story: those relating to the pose of the photographed subjects, their relatively neutral expression, captured at a frontal angle against a homogeneous background which prevents the viewer from looking away, and the iconic signs illustrating uniforms and work tools. In this iconic element, the photographic staging serves the process of creating a narrative that enables authentication of a subjective nature (referring to the knowledge of the photographed subjects), but mainly of an institutional nature (referring to the subjects being recognised as “CP railway workers”).

Third consideration: on strategies and managing expectations. In the icons, among other particular aspects, “verisimilitudes” are decided, the effects of meaning relating to “referential illusions”. This specific aspect of the photographic records is complemented by a symbolic element. The photographic record is not only the documentary testimony of a presence and the iconic record of a resemblance, but also the meaning of an intentionality, of a purpose evocative of an axiology structured and articulated in an ideology. It is on the symbolic level of photography that aesthetics gives way to ethics, vision to moral conviction, permeated by at least three elements: mine, as I conceived and produced this project; that of the museum - A Estação, which supervised it; and that of the people portrayed, in terms of their individual conceptions of what a portrait and an “authentic testimony” should be. On the one hand, a “productive ideology”; on the other, an “institutional ideology”; and finally, a “personal ideology”, which houses values referring to a status that is both subjective and professional, to an ethos that is also “corporate”, alongside “being a CP railway worker”.

These ideological elements are associated with ways of generating meaning, through which the photographic record has acquired a coherence. Veridiction modalities and veridiction contracts play a fundamental role in this process (Greimas & Courtés, 1993, pp. 417-419), and lead that which would be signified as an “authentic testimony” to result from the negotiated confluence of wishes and conceptions between the parties involved (myself, the museum and those portrayed).

In the case of the museum - A Estação, the “authentic testimony” was the result of a conception of a profession (as a railway worker), a corporate culture (having worked for CP and being retired) that determined a group of editorial expectations about what could and could not be photographed, what could and could not be reported. They were related to concerns inherent to the life stories. Nothing was reported or represented that was not directly related to the railway profession and the professional career at CP, despite the fact that there was equally interesting information gathered during the interviews and even during the visits, but not included here. These choices had implications not only for the content, but also for the way the photographs were taken. I have implemented this idea.

Madalena Nobre Rodrigues is in Figure 6. This image was originally entitled “Story of a Cat and Her Flag”, but was later changed to “Story of a ‘Cat’ and Her Flag”. It was explained to me that the word “cat” without inverted commas could give the text sexual connotations, when it was used by the interviewee herself (and reproduced in the quotation: “when I got married I came from Odemira to Montijo like a cat in a sack”) as a metaphor illustrating her recent youthful marriage and her later work at CP. I will come back to this, but to explain the difficulties that were involved in creating her portrait. In my case, expectations were related to production. For me, an “authentic testimony” would be the result of opting for a type of photographic staging (shown in the exhibition) and verbal expression (photobook). It would be the result of a multiplicity of technical options (flash with an sotfbox octobox along with a kicker light in a softbox strip with a grid on a burgundy background) and aesthetic specificity (the soft light refers to advertising photography; the pose, especially the position of the fingers, refers to paintings, both by Rubens and Leonardo da Vinci; the frontal or 3/4 pose updates aesthetic portraiture archetypes, specifically by Nadar and Disdéri). It should not be forgotten that this photographic staging was complemented by the text written and expressed within the style of a journalistic story (short paragraph, narrative synthesis, detailed recording of particulars), the life story (ethnography/anthropology/sociology) and the short story - with special emphasis on the narrative value of the denouement, where a paradigmatic writer emerged: Somerset Maughan (n.d.), with regard to his “Histórias dos Mares do Sul” (South Seas Stories), especially the novella “Chuva” (Rain).

In Figure 13 and Figure 14, it is possible to see different pages of the photobook that illustrate the relationships I wanted to establish between the photographs, headings and texts. Finally, in the case of the railway workers portrayed, the “authentic testimony” was also characterised by expectations arising from photographic modes of expression. In this regard, there are two episodes pertaining to certain difficulties in producing two portraits from the photobook, namely that of Madalena Nobre Rodrigues João (Figure 6) and José António Galhofas Carvoeira (Figure 7).

Credits. Eduardo J. M. Camilo

Figure 14 "Everything Goes With Discipline and Logistic”, photobook pagination

In the case of Madalena Rodrigues, with some initial difficulty, her portrait was created along with a kitten because it was intended to be a reenactment of the heading and a key phrase from her testimony, as I have already mentioned. The animal would, therefore, be the personification, the metaphor of her youth and the metonymy of the life story of a girl and young woman who gets married, is a housewife and mother and a worker at CP. This was explored as a significant element linking the portrait to the heading and the text. As for José Carvoeira, I could not even stage the heading (“Memories of a Boy Who Was Easter Lamb”). It concerned an incident in his life when he saw it threatened in a robbery at the station he managed, as he was very young when he began his career (“I joined the railway as a boy, and I was just an Easter lamb”).

These two are model episodes in this reflection on veridiction contracts and veridiction modalities: how the individual values of these railway workers were embodied in expectations (and desires) regarding the way they wanted to pose because they sensed that the portrait, being evocative of an ethos (“being”), would also imply a photographic expressiveness that seemed appropriate to them (“seeming”) which might not be compatible with what the photographer or the museum would like to be created. As I mentioned earlier, this particular aspect was already evident in the portraits of the bourgeoisie taken by Eugène Disdéri and Félix Nadar, in which the pose determined by the clients and, above all, the management of the appearance and the choice of clothing (“seeming”) were evocative of respectability, of a social class ethos (“being”). Why should it not be the same for these individuals, who wanted to “look good in the photograph”, that is, according to a set of expressive precepts (“seeming”) that “testified” in a coherent (that is, “authentic”) manner to their reputation as CP railway workers (“being”)?

These examples make it possible to understand how the meaning of “authentic testimony” is a dynamic process, which results from a negotiation, from “veridiction contracts” between parties: myself, the photographer, the museum and those photographed. In fact, the core of these disparities - sometimes more evident, other times more latent - can easily be explained by different photographic staging options: I based the project conceptually on a foundation hinged on “revelation”, a relatively obtuse expressive register (“not seeming”), that is, one that required deciphering, as if being a railway worker required the viewer to search for tell-tale signs existing both in the photographic records and in the accompanying texts, signs that progressively revealed the meanings of a subjective and corporate identity. This veridictory foundation was distinct from the conception of these two ex-railway workers: the more revealing the record was in its transparency, the greater the photographic clarity - as if there was nothing to hide or imply - the more “authentic” the testimony of their careers would be. The classic dichotomy between denotation and connotation is evident and, from a veridictory point of view, there are different expectations about a register involving secrecy (which is revealed and imposes hermeneutic activism - “not seeming”, but “being”) or truth (which is “given to the viewer/reader”, which is clarified - “seeming” and “being”).

What was done when this happened? Was the photograph, as a record, a symbol of the values of the photographer or of the photographed as to how an “authentic testimony” of a corporate identity should be signified? Which tug of war was more or less explicitly established?

In subjects such as ethnography and visual anthropology, where photography forms part of the field of participant observation, the answer is clear: the axiology that will prevail is the one that evokes the culture of the person photographed, although the ideal situation could be that of compatibility between the recording of culture - from an objective, even scientific perspective - and the “personalised” recording - from a subjective and artistic perspective. Given this, let us examine the project and see how it was indicative of a constant zigzagging, of “negotiations” to reconcile wills, and of disparate conceptions of what “authentic testimony” should mean. In the case of Madalena Nobre Rodrigues João’s photograph (Figure 6), my veridictory conception can be seen in a meaning that has to be “deciphered” and that is only revealed through the hermeneutic competence of the viewer and the reading of the text; on the other hand, José António Galhofas Carvoeira’s photograph (Figure 7) shows the transparency of a presence where everything happens in its immediacy.

2. Part II

I will now describe the project from a performative point of view, that is, as a product of processes involving the construction of meaning based on two main aspects, that relating to the production of the photographic (and verbal) record and that relating to its receptive context.

2.1. The Production Context

In this analysis level, the three protagonists mentioned above (the photographer, the museum - A Estação, and those photographed) interacted in a dialogical game of reconciling expectations and conceptualisations about the order of the meanings to be conveyed.

From the perspective of the photographer’s intervention, the work involved in the symbolic and iconic creation of a narrative has already been described: studio photography with flash (Godox 600 BM), shutter speed 1/125, aperture f:8. An exception to these images is a photograph of a former railway worker taken outdoors with the same flash, in which I tried to reproduce the same exposure value (Figure 5).

All the photographs in the project were edited in Lightroom and Photoshop, in a simple operation of adjusting the colour temperature and very occasional intervention work involving exposure, shadow and highlight values. The images that made up the corpus of the exhibition were printed on fine print, glossy paper in portrait layout, in a 60x70 cm passe-partout frame. As mentioned, they were exhibited in the foyer of the Pinhal Novo - Rui Guerreiro Municipal Auditorium in February 2023, and arranged to allow for easier circulation through the exhibition as well as to make it suitable for the space in which it was mounted (Figure 15). The stories in the photobook are not shown in the exhibition. Just the headings. I recognise that this particular aspect was a limitation. The project is characterised by a syncretic discourse and this has also defined its uniqueness. Therefore, the images displayed should have been accompanied by the respective texts.

As for the photobook, I have already pointed out that the portraits were complemented by a meaningful text about the life stories of the ex-railway workers - a text that was always titled and made particular by a final caption alongside the identity of the person photographed and their professional occupation at CP (Figure 14). These pages are complemented by others on the world of trains and rail transportation. The relationship between text and image is interdependent: in some testimonies, the images are a staging that allegorically conveys the meanings alongside the “testimonial authenticity” conveyed in the life stories testimonies. The photobook was produced using offset printing, in A4 format, as if it were a comic book, in a first print run limited to 150 copies.

These were the main production-related, specific features of the project in terms of its material aspects. I will now move on to consider immaterial aspects, those relating to the substance of the meanings conveyed, towards the underlying veridiction modalities.

What kind of meanings were conveyed from the manifestation level (“seeming”)? The words tell stories; the images stage fundamental episodes based on the way their protagonists have been portrayed. Underlying the recording - both photographic and verbal - I endeavoured to ensure that there was a dynamic of “progressive revelation” that would become its foundation. This specific structural aspect of “revelation” had already been put in motion in the stage involving the visits and testimonies carried out by the museum, which the photographic project complemented. However, unlike these initiatives, in which railway workers told their stories, I wanted the record not to be transparent, in other words, not to allow for instant and explicit meaning concerning biographical and corporate data. This was a personal stance I assumed from the outset: the report would be more than a “list” of facts, more than a testimony strictly speaking, but rather a gradual experience of knowledge, of discovery. For this reason, the headings would not be obvious either and would impose figurative meanings, especially in correlation with the photographs, the staging of props and poses which would force interpretations to go beyond the denotative level. As such, I wanted to impute an obtuse expressiveness to the recording that, as I have already mentioned, has sometimes provoked (latent or obvious) controversy in some of those portrayed, an expressiveness that would force an interpretation that could no longer be made “literally” or from the transparency of the composition. In considering that the testimonies would be signified in a figurative sense; that they would not be transparent; that they would be hidden; that, in order to be interpreted, it would be necessary to go beyond what was photographed, reported or exhibited, the veridiction modality I opted for in this project would be that of “secrecy”, that of a “not seeming (but) being”, capable of imposing an active form of interpretation which involved “deciphering” on the part of the viewer. This option contrasted with the veridiction modality of “truth” (“seeming-being”) - a transparency of the senses assumed by some of those photographed.

In addition, I have expanded on certain ideas about this veridictory singularity leveraged on secrecy because it has enabled me to establish certain distinctions between this project and other textual genres that also convey meanings related to testimony based on expressive records that reconcile photography with words. I am referring to the visual anthropology/ethnography essay and a type of journalism based on the “visual chronicle”, photo reportage. These records also reveal a relationship between the recording of testimony and the significance of a “revelation”, whether of a journalistic nature - that is, related to a news value - or anthropological - that is, referring to a scientific-cultural value. But the veridictory dynamic of these records differs from that which I chose. In one case, “transparency”, which translates into ease and/or speed of reading: both reportage and ethnographic research show/read clearly, as they are records of revelation. In the other case, the “opacity” makes the meanings implicit, requiring interpretative consideration and activism.

2.2. The Reception Context

Are the records of photojournalism and visual anthropology more effective from a communicational point of view, compared to this project, which is more “obtuse”, “more mysterious”?

It is difficult to answer this question without leaving the semiotic plane of text and image towards one of sociological communication, that is, a plane for analysing the “uses and gratifications” of texts. What I can say is that all textual practices are underpinned by veridictory dynamics that produce meaningful effects (and, necessarily, pragmatic effects). Those of transparency, referring to the meaning of “truth” and “objectivity” or “authenticity”, in photo reportage or visual anthropology and ethnography, or those of “discovery”, “deciphering”, inherent in certain photographs and texts that I have created. All these veridictory dynamics are based, from the point of view of the photographic record, on a stadium (Barthes, 1980/1988, p. 46), a voluntary or involuntary intentional and planned composition, which is all the more evident the better the record is overdetermined by figurative meanings, that is, by typical dynamics of connotation. This is something that meekly awaits the spectators’ interpretation (Barthes, 1980/1988, pp. 45-46). A great distance necessarily lies between what has been conceived, studied and ingeniously composed, staged and intended between the range of expectant connotations, from the perspective of their availability in the photographic and verbal records, and the viewers’ actual cultural repertoire, through which they will be able to recognise, interpret and sanction the piece. I recognise the existence of an insurmountable margin of

(interpretative) error, as if the virtual record of the studium were always beyond the interpretative capacities of its recipients. What will the readers of the book or the spectators to the exhibition have understood from this project? And is what they have understood in line with what I would have liked them to understand? In addition to this interpretative “margin of error”, another fundamental factor will interfere in the process of reception and interpretation: the unforeseen, everything in the records that is capable of spontaneously jumping into the viewers’ senses, of meeting them halfway; the elements that disturb the sense of the studium that are present in the photographs, but which have not been considered or intended, being complementary or capable of frustrating and relativising what I would have wished them to have seen and interpreted. I am referring to the punctum, to those arrows that erupt from the photograph and wound the senses in the direction of other repertoires and knowledge (Barthes, 1980/1988, pp. 46-47).

From the moment this project was created, it became absolutely free, forever beyond the control of all those who competed to produce it.

3. Conclusion

I have tried to formulate certain considerations with reference to a project developed and supported by the museum - A Estação (Palmela Town Hall), which included an exhibition and the publication of a photobook of portraits and memories of former CP railway workers. The first, relating to the area of “life stories”, refers to the documentary and testimonial aspect of photography, from which it is possible to develop a reconstruction of the moments that underpinned the photographic record. From a semiotic point of view, this is associated with photography’s status as an index, that distinguishes it from other images that do not possess such a vocation (as is the case with synthetic images). The second consideration to highlight arose from the iconic and symbolic aspects, which also semiotically specify the photograph, but by giving it a gravity and complexity that impose the need to conceptualise this as a reality of meaning where a fictional element is generated and managed. The fiction of reality - in which life stories are transformed into the lives of history - posed questions to me: from an iconic point of view, to what extent did the effects of meaning derive from a truth in these photographs (a truth which was conceived in an epistemological and semiotic context based on the referential link between signs and objects) or rather derived from a verisimilitude, that is, from a “referential illusion”? And, in addition, to what extent did the photographic record reveal a symbolic dynamic associated with an ethic, an axiology, in short, an ideology? Two important questions, omnipresent within this project, the answer to which I discovered based on the options underlying the “staging of the testimonies” and the criteria evident in an expressive work based not only on a process of knowledge (of “doingknowing”, therefore alongside the signification of an identification), but above all of recognition (of “doing-believing” - the signification of an institutional identity - “being a CP railway worker”).

Also on the symbolic dimensions of the photographs, I formulated ideas about the semiotic phenomenon of veridiction: how the portraits of these ex-railway workers - combined with a verbal record similar to the chronicle and the short story - would be significant in an aspect that reflected conceptions referring to meanings about “authentic testimony”. These are negotiated conceptions, agreed in a contract (involving veridiction) between the parties involved in this project: myself, who created it; the museum, which approved and supervised it; and the ex-railway workers, who appeared in the portraits and provided their testimonies. This negotiation, more or less assumed or latent, became an expressive dynamic with implications for the way I “constructed” the photographic studium, which was based on a pendular movement concerning complementary veridiction modalities: that of secrecy - from which the meaning of the “authenticity of the testimonies” emerged as the end point of a searching process, of deciphering by reference to a figurative discourse, assumedly connotative; and that of truth - by reference to a transparent, clear and evident discourse, mainly involving the aspect of denotation.

Referências

Adam, H. C. (Ed.). (2008). Os índios norte-americanos (C. S. de Almeida, Trad.). Taschen. (Trabalho original publicado em 2001) [ Links ]

Andrade R. de. (2002). Fotografia e antropologia: Olhares fora-dentro. Educ; Estação Liberdade. [ Links ]

Baptiste, J. (2009, 9 de novembro). Pierre Verger - Candomble. JB: This and That. http://jennylbaptiste.blogspot.com/2009/11/pierre-vergercandomble.html?m=0 [ Links ]

Barthes, R. (1988). A câmara clara (M. Torres, Trad.). Edições 70. (Trabalho original publicado em 1980) [ Links ]

Bateson, G., & Mead, M. (1942). Balinese character. A photographic analysis (Vol. II). New York Academy of Sciences. [ Links ]

Cabrita, A. (Diretor). (1978). Histórias de comboios em Portugal [Documentário]. Rádio e Televisão de Portugal (RTP). [ Links ]

Camilo, E. J. M. (2023). Linhas com cruzamentos de destino. Câmara Municipal de Palmela. [ Links ]

Frizot, M., & Ducros, F. (Eds.). (1987). Du bon usage de la photographie. Une anthologie des textes. Centre National de la Photographie. [ Links ]

Gomes, G. (1995). Barreiro. Fotografias anos 4 0-60. Câmara Municipal do Barreiro. [ Links ]

Greimas, A. J., & Courtés, J. (1993). Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage. Hachette Livre. [ Links ]

Kossoy, B. (2012). Fotografia & história (4.ª ed.). Ateliê Editorial. [ Links ]

Kossoy, B. (2021). Fotografia e história: As tramas da representação fotográfica. Projeto História, V(70), 9-35. https://doi.org/10.23925/2176-2767.2021v70p935 [ Links ]

Maughan, S. (s.d.). Chuva e outras novelas (3.ª ed.). Livros do Brasil. [ Links ]

Sanches, F. D. (2017). A fotografia como narrativa antropológica. Ponto URBE, (21), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4000/pontourbe.3516 [ Links ]

Received: March 24, 2023; Revised: August 16, 2023; Accepted: August 29, 2023

texto em

texto em