1. Introduction

The “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) is a gigantic geopolitical and geostrategic plan to bring China to an all-new level in the international system, trying to depose the United States (US) of the global leadership as it presents today, on military, economic and global reach basis. So, China’s regional neighbours, e.g., Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, just to name a few, have a role to play in this international project. Furthermore, the purposes of the various roles that these countries will perpetrate are strategic in perspective and nature, thus representing various Chinese interests on the guise of a multilateral initiative bringing various beneficial consequences to all parties in question, at least this has been the general Chinese discourse about the issue.

In South Asia, the increasing degree of competition between India and China has raised the stakes, because until BRI emerged, India did not felt so threatened by the bilateral relationship between China and India’s neighbours, but with the realization that BRI and all its efforts had a strategic thought in essence, and China’s rising as a regional power, brought to mind that New Delhi as to compete or respond to this opposing country and its infrastructure development projects.

Notwithstanding that the reach of the BRI is global, for this article I’m just going to focus on the Pakistan-China relations and the consequences that this partnership represents in the regional area, both for India, and for the regional balance of power.

Taking into account that India and China are both the two competitors for influence in Asia; the two are states included in the BRICs group, therefore having an economic power-house and growth that is ingenious; the two are almost, as politically speaking of their regimes, antagonist, in the sense that India is a democracy and China an authoritarian state; India is a West partner and China is a West competitor; both of these states are at the top positions for the two largest countries by population, by the World Meter statistics (2020) - in June 2020 -, being that China occupies the first one and India the second. Therefore, China and India are two ends of the same sword in a crowded continent and in a region that much as to offer in terms of resources, access to the main maritime routes and, potentially, the future global centre of financial and technological power-houses, in the sense that China is promoting its shift from industrious focused economy to a technological one, e.g., ‘Made in China 2025’ policy and the BRI that will focus immensely in the internal development of China and on the internationalization of its currency, the renminbi (RMB).

So, it’s only logical that the two regional powers will clash for dominance in the area, lets remind the ‘Thucydides Trap’, even more if one of them is becoming a closer and closer ally on political, economic and social basis to Pakistan, the forever antagonist of India.

In this context, the presenting paper will focus on the China-Pakistan relations, in the broad sense of the BRI, with a special insight about the consequences that this relationship, materialized in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), will bring to the regional balance of power between China-India, as so what is the Indian perspective to BRI and CPEC in particular.

Notwithstanding, CPEC gives China the opportunity to promote a “Look West” policy to further its ties with the main energy sources of Central Asia, e.g., Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan (Javaid, 2016), withal that promotes an eclectic approach to the economic hubs of Europe.

In an all Indian perspective, CPEC and the China-Pakistan relations are a dangerous playfield for the regional interests of India, inasmuch as their ties, remoting the year of 1950 when Pakistan was the first Muslim and the third non-communist country recognising China as a state, are bolstered by a collective discord with India, so their friendship can be analysed as an alliance with a common foe - India - and Pakistan can have a balancing role to tie down the latter (Mishra, 2015). Therefore, India is in a ‘straitjacket’ by two neighbour countries with one that have the supreme interest in minimising the Indian room for manoeuvre, as the ‘string of pearls’ so astonishingly represents.

2. China-Pakistan Relations: CPEC as a Devolvement Model or Strategic Plan?

The 3,000 km economic corridor is the leading project of China’s ambitious vision for a modern reconstruction of the New Silk Road. This project was proposed in 2013 by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, the same year that the former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif took office, with the mission for reinvigorating the economy. Notwithstanding, this project is planned to end in 2030.

The CPEC is considered a ‘game-changer’ for Pakistan, because the initiation and launching of this economic corridor is a significant economic activity that will boost the Pakistani economic drive since the fall of Dhaka that lead to the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, in as much as that in the meantime Pakistan has been in the midst of a grand regional turmoil, e.g., the soviet invasion in Afghanistan, the Iran-Iraq war, the Kuwait war, the continuous turbulence of Afghanistan and the continuous nuclear test by both India and Pakistan.

In this respect, the BRI and the launching of CPEC in 2013 contributed for an increasingly insight that there was a ‘light at the end of the tunnel’, since it is perceived as a strong ray of hope for the economic regain through integrated investments in energy, trade and communication (Farooqui & Aftab, 2018).

Pakistan, geographically speaking, has an important feature, because it’s placed right at the junction of South Asia, West Asia, Central Asia and Western China, being in a strategically region for world trade, and for an important relationship with China, in the sense that Pakistan is the shortest route to the former towards Middle East and the EU (Javaid, 2016), provided that China needs an incredible amount of natural resources, namely energetic ones, it’s of an exalted importance the creation of pipelines and hard infrastructures to connect China and the source of energy avoiding, at the same time, choke points like the Malacca Strait, of the Paracel Islands.

CPEC is aiming to connect and enhance trade activities through Pakistan between China and the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia, owning to that, this project is considered as a fast-track of hard infrastructures to interconnect the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ and the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’, creating a severe network of highways, railway lines, natural gas and oil pipelines form the Central Asia countries connecting Kashgar, the north-western city of China and the port of Gwadar, so that it can be shipped through maritime routes.

As stated by professor Umbreen Javaid (2016): “when the corridor will be operational, it will function as a doorway for trade between China, Africa and the Middle East. In particular, oil from the Middle East can be deposited at Gwadar and carried to China via Balochistan that will lessen the 12,000 km route that Middle East oil supplies takes to reach Chinese ports”. Therefore, the interconnectivity and Chinese-Pakistani relations are of extreme strategic importance for the former.

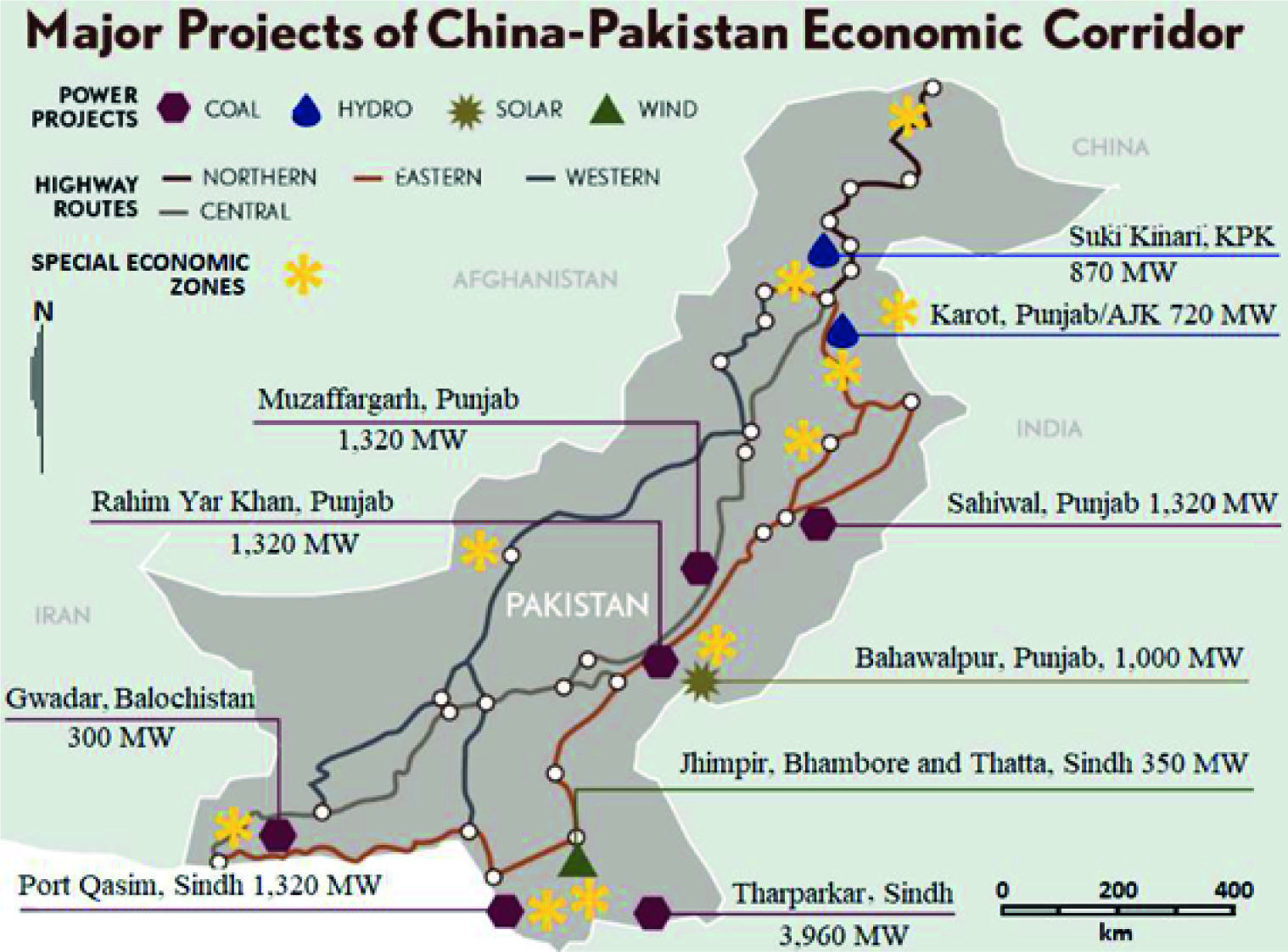

This project will focus on four main areas of interest, that will be the focus of the Chinese industrial investment and Research & Development (R&D), as mentioned by the Prime Minister’s Office Government of Pakistan (BOI, 2017):

Construction of highways and railway tracks;

Development of Gwadar port;

Laying down pipelines for oil and gas transmission;

Establishing of industrial zones along the CPEC route.

It has been estimated that CPEC will increase the Pakistani GDP steadily through the course of the project (Yu, 2018), ensuring that Pakistan can and will be a major regional economic player. On the other hand, with the implementation of CPEC, Pakistan will be a trade and commerce hub that it needs numerous industrial and economic zones, physical roads and railways linking the both players. Therefore, the project is divided in four main routes, as we can see in the figure above, each one with its opportunities and vulnerabilities (Javaid, 2016).

Pakistan and China are now moving in the era of geo-economics and towards an increasingly connectivity via the different areas of cooperation like as verified by the innumerable Memorandums of Understandings (MoU’s) signed by both.

This project is $ 46 billion worth of infrastructure development that is equal to roughly 20 per cent of Pakistan’s annual GDP (Stevens, 2015), not to mention that China is the number one source of foreign investment in Pakistan with $ 1,812.6 million on the year of 2017 (BOI, 2017). The split for this investment can be divided by the following areas: energy related infrastructures, transport infrastructures and for the development of the Gwadar port. The chairman of the Pakistan-China Institute, Mushahid Hussain emphasized that the economic corridor “will play a crucial role in regional integration of the ‘Greater South Asia’, which includes China, Iran, Afghanistan, and stretches all the way to Myanmar” (Tiezzy, 2014).

This massively corridor of infrastructure promoting trade raging through Pakistan is a staggeringly important part for the ‘Vision 2025’ proposed by the Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform of the Government of Pakistan in early 2014, to serve four specific functions. The first one, is to give some predictability for internal and external stakeholders regarding the future and the direction of the nation, so to speak, is to cement the image of stability and as a good investment target. The second one concerns setting out future goals and expectations, translated in the concrete policy’s. The third regards the conceptualization of a platform for the revival of sustainable and inclusive growth, to achieve the aimed international development goals settled by the Government, at all levels, economically and human development levels, as to compete with other neighbourhood countries, e.g., Bangladesh, China, India, South Korea, and Sri Lanka. Finally, it will provide the indigenous conception and approach for meeting all globally agreed targets, e.g., Millennium Development Goals and the “new” Sustainable Development Objectives. In that sense, the document envisions seven pillars with several quantitative targets for each one, as to increase primary school enrolment and completion rate to 100% & literacy rate to 90%, become one of the largest 25 economies in the World, leading to Upper Middle Income country status, increase annual Foreign Direct Investment from USD 600 million to over USD 15 billion, rank in the top 50 countries on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Rankings, increase road density from 32 km/100 km2 to 64 km/ 100 km2, and share of rail in transport from 4% to 20%, among others.

To this end, the ‘Vision 2025’ is document presenting the changed mentality of Pakistan from a under-development country logic, to a developed one, concerning the international competitors, the imagery that transmits to the external actors, and to ascend become more independent from other stakeholders, like China. Nevertheless, as stated by the Pakistani ambassador to China - Masood Khalid (Chao, 2019): “the Vision 2025 program by the government of Pakistan and the Belt and Road Initiative of China are perfectly aligned because many things in Vision 2025 are common elements in the Belt and Road Initiative […] Pakistan will benefit from more trade and more economic prosperity, more productivity, more employment and a better communications network. All the regions in this connectivity network will benefit”. These common elements are the increasingly connectivity to other bigger and profitable markets and infrastructure development (stated as the Pillar VII of the document), poverty relief with the creation of more jobs (stated as the Pillar I of the document), strengthening the private growth with the new hard infrastructures created and increased connectivity (stated as the Pillar V of the document), energy development (stated as the Pillar IV of the document).

Taking all of this into account, the CPEC has a lot of challenges paramount to its implementation, in one sense, it has generated massively controversies between the provinces and the federal government of Pakistan, regarding the regions that will not benefit from the infrastructure development and the economic projects as the region of Balochistan, that feel left behind cementing the everlasting sentiment of negligence and ignorance by the Pakistani central government (Baloch, 2016). The economic corridor provides special tax incentives to Chinese companies which swamp the Pakistani market and provide unfair competition (Rehman, 2017). The major militant organizations operating across Pak-China Western strip have been a source of continuous trouble for the development of the project, posing serious threats to the implementation of the initiative, as of the Uighur militants (Sial, 2014). In that respect, there have been attacks on the Chinese nationals working in the project in order to frighten them, as a major part of CPEC goes through the Punjab area, a insurgency-prone zone with the presence of rogue elements which are against the project (Afzal & Nassem, 2018).

2.1 Gwadar Port: The Strategic Assent for China

This port is in a strategic position all together, in the sense that is the third largest port of the world, it’s located at the doorway of Strait of Hormuz, at the shore of Arabian Sea, near the Persian Gulf. Basically, it’s of extreme importance the development of this port inasmuch it is close to several important sea routes through which a great percentage of the world’s global oil shipments pass and to store oil coming from the Middle East that can be posteriorly pumped through the proposed pipeline to China.

Gwadar, consequently, reveals itself as an asset for both China and Pakistan, in view of the fact that in the perspective of the former, interconnecting the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ with the ‘Economic Belt’ through Pakistan and reaching this port is of extreme strategic and economic advantage to China, owning to the fact that in this way China can circumvent choke-points located in the South Asian Sea, diversifying its routes of oil transportation, reduce immensely the time of transport, concomitantly, export its goods coming from the interior regions through Kashgar, capitalizing the land and the sea. For Pakistan, the advantages are in plain sight, because it will have an increase of regional development, as I aforementioned, and it’ll cement on a long-lasting relationship with China, that is valuable assessing the neighbour country of India and the power-relations of the two. At the same time, the port can have a geostrategic advantage because it can serve as a point for surveillance to monitor naval activities in the entire Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean (Kalim, 2016).

On 14 November 2016, Gwadar port was fully operational and was inaugurated by the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, becoming a luff of fresh air for the economic uplift and development of China’s hitherto Xinjiang region and the ‘Go West’ policy. In the other hand, 29 January 2018 marked the first phase of Gwadar Port’s Free Zone, that in the words of Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, the free zone will help facilitate regional and global trade under the CPEC (Xinhua, 2018). At the same time, it’ll boost the international trade and the normalization of the relation between Pakistan and its regional neighbours, Afghanistan and Iran, becoming both beneficiaries of the transit trade to Central Asia.

In this respect, with almost half of its oil imports passing through both the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca, China is conscious of the imperative need to augment its political and security influence in the region area, in the sense that it needs to connect Gwadar port overland to Chinese western regions, namely Xinjiang, attains great significance (Ishaque, 2016). Nevertheless, reaching Iran and Afghanistan through Pakistan and not from the Central Asia brings fruition to the fact that is necessary, by both the concretization of BRI and maintaining regional peace, to avoid competition with Russia for strategic depth in what Russia perceives as its near abroad and sphere of influence.

3. Indian Perspective and Security Risks

India only begun to debate the consequences of the BRI when China deepened its infrastructure engagements with India’s neighbours in South Asia and the Indian Ocean regions. Hence, all of this has created a sense of unease in New Delhi, capitalizing in the fact that the rising Chinese power in the region and the growing influence in South Asia, brings to bear that India as to respond or try not to fall in the strategic web that is materialized by BRI (Baruah, 2018).

India has started to craft a policy response, e.g., not attending the Belt and Road Forum that China hosted in May 2017; questioning the initiative’s transparency and processes and opposing CPEC due to concerns about territorial sovereignty. As in such, India as rejected the proposal to be an integrated part of this initiative with the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM) (Ayres, 2017; Leandro, 2018). Concomitantly, India sees CPEC as a strategically project that to fully function needs to pass through the Karakorum Highway, that at the same time, passes through territory called Gilgit-Balistan that was originally part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, which the latter is contested by both Pakistan and India. So, aside all this, India also sees what is the rational of the Chinese investment, e.g., ‘checkbook diplomacy’ in the African cases and the Sri Lanka one, accessing that their development orientated investment is all a strategy by China to gain control of the infrastructures and resources that that countries have, therefore not having a transparency nature, evolving Chinese partners in immense debt.

In essence, China’s rising influence in the region materializes to some key concerns for India, as such: the Chinese projects may run afoul of accepted international standards and norms; undermine Indian sovereignty claims on disputed territory; grant China greater geopolitical influence, in particular by hand of the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’, given that the Indian Ocean is perceive as the Indian backyard, so it’s only logical that growing influence in this region brings to bear concerns for India.

To have a fully perspective about the Indian thought of all this matter its helpful to examine four specific corridors that constitute major components of the BRI and utilise the geographic positions of India’s neighbours: CPEC and the ‘Maritime Silk Road’; BCIM; Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor (Baruah, 2018).

3.1 China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the “String of Pearls”

New Delhi’s concerns about CPEC has focused on three main subjects: territorial sovereignty, security, and the deepening China-Pakistan strategic partnership. China’s apparent disregard for territorial sovereignty in India’s neighbourhood is and will be the long-standing concern that originated in the 1970s, when India opposed the construction of the Karakoram Highway through Kashmir, in this sense, CPEC projects have restored these concerns about the integrity of the Indian perceived territory.

One of the most pressing concerns about CPEC is a sustained Chinese military presence in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, bringing to question that the India-China relations since the territorial disputes over a border along the Himalayas in northern and eastern India, on the Doklam plateau and in its border in Arunachal Pradesh, presents to India a perceived threat, whereas any further increase in Chinese troops along India’s borders would be a serious affront to India’s security (Baruah, 2018).

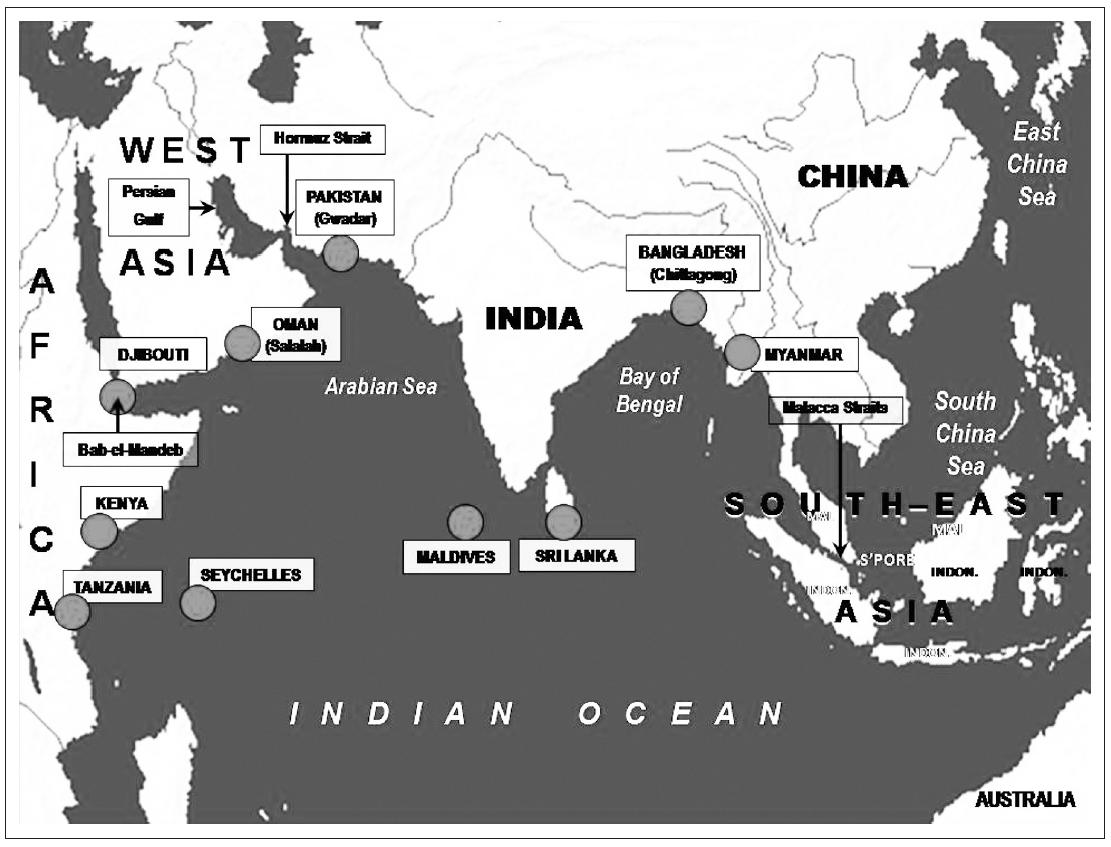

The construction of ports perpetrated by China encircling India, in the famous ‘string of pearls’ strategy, as we can analyse in the Figure 2.

Aside this discourse, China never mentioned, officially at least, that this was the case, of a grandee strategy to encircle India, although recent actions indicate this stratagem being used from the South China Sea to Djibouti and in between CPEC and Gwadar development, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, the port construction in Myanmar and Bangladesh. As stated by Brewster (2018):

China is now moving faster than many expected to build a military role in the Indian Ocean. This includes the development of a network of naval and military bases around the Indian Ocean littoral, starting with Djibouti (opened last year) and a new base likely to be built at or near Gwadar in Pakistan. Further Chinese bases are likely in East Africa and perhaps in the central/eastern Indian Ocean. A network of bases-of varying types and size-will help maximize China’s options in responding to contingencies affecting its interests, including support for anti-piracy operations, non-combatant evacuations, protection of Chinese nationals and property, and potentially, interventions into Indian Ocean littoral states or other regional countries. It is unlikely that China will be in a position to challenge U.S. dominance in the Indian Ocean for some years to come. But it will be poised to take advantage of strategic opportunities or step into any perceived power vacuums.

Gwadar helps lead the BRI a maritime dimension and India views this project as part of China’s strategy to augment its maritime projection in the Indian Ocean region. Many in New Delhi expect that the port will emerge as an important naval base for China, as it can be observed in Djibouti, serving as a key node in China’s ‘String of Pearls’ (Rogin, 2018).

In this context, Gwadar port can potentially serve a role bigger than a ‘simple’ connectivity hub for the Pakistan and China trade and an escape route for the latter. This port, prospectively, can be an important foothold for the ‘String of Pearls’ strategy, in respect of, if this port was to be converted into a naval base, it would enable the Popular Liberation Army Navy to maintain a persistent presence in the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman, putting India in a obstinate position regarding energy supplies from the Gulf and maritime trade would be increasingly vulnerable to interception (Kanwal, 2018). Consequently, already in respect for the US political apparatus, they claim that “China [reportedly] is about to start construction of a naval base and airfield at Jiwani, some 60 kilometers west of Gwadar” (Brewster, 2017), aiming to create an increasingly connectivity between this supposedly naval base and the effective base at Djibouti, accessing Karachi and controlling both the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, contracting the possible Indian strength at the Arabic Sea.

The creation of some of this ports by the BRI and with the publication of its biennial Defence White Paper titled ‘China’s Military Strategy’ (2014), it was an awareness alert for scholars in the United States and in India that China was, possibly, building an encirclement for India, in the sense that in case of an armed conflict, such overseas military bases would be of much valuable for China to protect the access to energy resources and they would represent bases for logistics support to the maritime-military forces in the region (Khurana, 2015).

To counter the CPEC and the geopolitical power of Gwadar, India has promoted a trilateral agreement between the latter, Iran and Afghanistan, of a massive sum for Indian investment on the development for the Chabahar Port complex and for its expansion to Zaranj in Afghanistan via railways. Capitalizing on this fact is key for India to try minimizing the impact of Gwadar, according to the Indian Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale, “we are also seeking to develop the Chabahar Port as a gateway for onward connectivity to and from Afghanistan and Central Asia” (Chaudhury, 2018a). Nevertheless, this port will serve as a growth engine to the three parties evolved and for several Central Asia countries, avoiding Pakistan and to cope Gwadar port, accessing the fact that Chabahar is very close to the latter and its access to the Indian Ocean Region can reduce the distance for products from Central Asia to reach India, namely Kandla and Mumbai regions, fomenting cargo transport, trade and business.

Another way to try to cope with the Chinese influence and presence in the Indian Ocean region is strengthening Indian security ties with Maldives, Mauritius and Sri Lanka, stepping up naval engagement with the littoral states of the Bay of Bengal, at the same time that engages in other forms of collaboration with Australia, Japan and the United States to maintain the current security environment and protect its strategic and security interests (Baruah, 2018).

3.2 Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor and the Friendly Neighbours

This economic corridor seeks to connect the Chinese city of Kunming with the Indian city of Kolkata through Dhaka in Bangladesh and Mandalay in Myanmar, with the end of boosting trade, promote infrastructure development and connect the undeveloped and landlocked part of north-eastern India and Southwestern China. This initiative has been in the discussion area since the 1990s, but when the BRI appeared the BCIM was integrated into the grand project, as the other economic corridors proposed by China.

In the words of Darshana Baruah (2018:17) “India and China have consistently expressed diplomatic support for the BCIM Corridor, keeping in mind the need for dialogue in the Sino-Indian relationship. However, despite this positive rhetoric, much of this enthusiasm is largely symbolic; effective cooperation through the BCIM Corridor has been seriously limited.”

This is true in the sense that India is in favour of cementing more all-around relations and regional interconnectivity, however India sees little to no room of collaborating with China in this corridor currently, even so, it’s uneasy of working with Beijing and its strategic plans materialized by BRI.

In this context, apart from the BCIM there are obstacles to the realization of this project, as such the various territorial disputes and border incidents between China and India, represent. Therefore, there is a mistrust from the Indian part of becoming a partner with China, as long the latter continues to enlarge its sphere of influence to the subcontinent and to the Indian neighbours.

India as promoted, in 1997, the creation of its own economic corridor to boost the trade, connectivity and cooperation with the ‘Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation’, offering a regional multilateral organization to fulfil those ends. This project is integrated by Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Thailand, i.e., right in the subcontinent area and adjacent region, so India can maintain its sphere of influence alive (Xavier, 2018).

3.3 The Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor: Nepal as the ‘Squashed´ State

The Himalayan Economic Corridor was a bilateral proposal between Nepal and China, being now part of BRI. This project promotes the creation of a corridor across the Himalayan Mountains passing through the Chinese autonomous region of Tibet and reaching Kathmandu. Nevertheless, Nepal in recent actions as made clear its intent of being the intermediate country between India and China, with the increase of railways, roads and infrastructures, so that it can become more developed and gain accesses to the southern Asian countries through the connective infrastructures planned. The former Nepalese Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal in 2010 has voiced that “trilateral strategic relations” are necessary to the full development of the project and the region (Rana, 2017). In this sense, India prefers Nepal as the Himalayan bridge economy for national security reasons, so it can form a ‘buffer-zone’ with China, at the same time creating commerce and trade. Hence, the Indian desire of working bilaterally with Nepal and not in a trilateral faction, giving support to construct a rail-link between India and Kathmandu, and prop accesses to the ocean through inland waterways (Chaudhury, 2018b).

China with this project intends to create an alternative to Kathmandu’s traditional reliance on Indian ports for trade, by improving its connections with other countries, notably China and Pakistan, by proxy.

The Indian reserves about the China-Nepal relations are evident in the sense that increase Chinese influence in Kathmandu can promote more military and Chinese presence altogether in the close borders of India.

3.4 Shanghai Cooperation Organization: The Forum of Controversies

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is in part relevant to understand the bigger picture regarding the relations between Pakistan and India, in the foremost these states are full members of the SCO since 2017, but this fact was received with scepticism inside and outside the region, for the reason that this international organization, created in 2001, serves de purposed to augment the cooperation in the security sense between all of the members, notwithstanding it also strives to further strengthen mutual trust and good neighbourly relations. In that sense, the Chinese rational to include both India and Pakistan is this organization (it goes without saying that SCO was the first ever international organization created by China, in it’s all to purpose to respect and regard international norms and create new international mechanisms serving Chinese interests, as of SCO, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and BRICS New Development Bank) was to turn SCO relevant in the international arena, as of this organization now covers 60 percent of the Eurasian landmass and almost half of the world’s population with a collective gross domestic product of almost 25 percent of the global total (Seiwert, 2019).

In this context, SCO as an organization to increase cooperation regarding security matters, as of dealing with terrorism, separatism and extremism, it has received a lot of criticism because of its inefficiency, e.g., publishing a noncommittal statement regarding the 2010 revolution in Kyrgyzstan, deadlock of the key SCO institutions concerning the management of the Western withdrawal from Afghanistan (Weitz, 2014). Despite this problems, there are other concerns related to SCO irrelevance as an international organization, as of the increasing suspicion by its members, foremost the two central states China-Russia, and divisions in foreign policy and direction of all the members.

Concerning Pakistan-Indian relations, SCO has taken a role of giving some frameworks to China and Russia to ensure peace in the region, as in the conflict erupted in 2019, when a suicide attack on an Indian paramilitary convoy in the Pulwama district of Indian-administered Kashmir in February lead to an escalation of the belligerences between the two countries, and in this context China and Russia offered to assist in defusing tensions and proposed using the SCO Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure, but with little consequences (Barabanov, 2019).

So, the SCO as a whole is irrelevant to maintain the peace between India and Pakistan, or to descaled hostilities, given that the member-states choose to bilaterally cooperate with the same members of the organization, regarding their mutual doubt and asserting their non-interference principle. It must not be forgotten that the creation of SCO was to assert China power and control the other regional powers, as Russia, in this respect the SCO is more as an appearances international organization than a suitable forum of cooperation, concerning the ever present Indian and Pakistan hostilities.

4. Conclusion

In sum we can assume that the relationship between China-Pakistan has induced numerous reverberations on the regional stability, or in other words, the regional balance of power, according as the various projects that the two states prementioned realized, being the CPEC and the development of Gwadar the two perfect examples, provoked in India a sense of threat and the sentiment that this state has to do something to counter the strategic designs of China, bringing into question, not a military clash, although forces by both sides already confront each other at the disputed borders, the power-relation between those two are fundamentally materialized on projects to gain more influence in the region, e.g., BRI, CPEC, BCIM, for the part of China, and the trilateral accord of India-Iran-Afghanistan, India-Nepal, India and countries from the ASEAN and the ‘near-abroad’.

Notwithstanding, India perceives the greater regional and global role pursued by China utilising the discourse of mutual development and ‘no strings attached’ investment with scepticism, in a way, because the Indian leaders recognize the strategic nature of these projects, and as an affront to the regional and global role that India wants to itself becoming the two states, competitors. On the other hand, India comprehends that China wants to ‘encircle’ and ‘strangulate’ it by aligning itself with state neighbours. Consequently, obliging India to seek other countries outside its traditional sphere of influence, e.g., United States, Japan, Australia, Iran, Afghanistan.