1. Introduction

1“I've been planning this for a few weeks now and I'm trying to launch myself from one blue-beam-tower to the other in Halo. I haven't started yet but I need to launch myself up several times for the grenades and a Warthog on each tower. I also had another great (read: impossible) idea but it was too hard and I can't remember what it was”.

On September 10th, 2004, the user Grenadesticker posted the above message on the HighImpactHalo forum as a reply to the thread "What are you working on? #74" started the day before. Grenadesticker’s message started what would be one of the biggest challenges for the community of players of Halo: Combat Evolved (Halo: CE), the first game of Microsoft’s Halo franchise, released in 20012. The challenge, known as the Tower-To-Tower Challenge, or T2T Challenge, can be summarized as this: to make Master Chief - the character controlled by the player and the protagonist of the game and the entire franchise - perform a jump between the two Blue Beam towers of the level "Halo," from the aforementioned Halo: Combat Evolved. Contrary to what it might seem at first glance, accomplishing this feat is not easy, as the game's developers did not design this particular action. In fact, there is no way to make the character climb any of these towers, let alone make the jump. For such an undertaking to be achieved, players would have to discover several tricks in Halo's gameplay3, even so without any guarantee of success. In addition, performing this jump would not add anything to the objectives proposed by the game: it is a tautological challenge whose only aim is to perform the jump itself, keeping Master Chief alive by falling on the second tower. Finally, in June 2011, almost seven years after the first attempt, the user Duelies beat the challenge4, a performance duly recorded in videos and posted on his YouTube channel (Figure 1).

As is common in the video game scene since its commercial beginnings - at the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s - players seek to perform actions that were not foreseen - designed and programmed - to occur within a game. Whether through the exploitation of bugs in the system or through the invention and/or discovery of unprecedented actions, the history of video games is full of glimpses that would surprise even the game designers and programmers of a given game. These unforeseen actions are directly related to what Vilém Flusser designates as the act of "exhaustion of the program," of fighting "against the photographic apparatus," seeking to extract images never taken before (Flusser, 1985). In Flusser's words:

(Flusser, 1985).“A device is a toy and not an instrument in the traditional sense. And the man who manipulates it is not a worker, but a player: no longer homo faber, but homo ludens. And such a man does not play with his toy, but against him. He tries to exhaust the program. So to speak: it penetrates the apparatus in order to discover its tricks”

Analogously, scrutinizing the apparatus, in this case, the video game, is "unveiling" the contents of a black box - made to operate within the limits of who programmed it - extracting new possibilities for creative acts from it.

Maude Bonenfant (Bonenfant, 2015) calls such actions, when carried out specifically in the context of games in general and video games in particular, ludic appropriation (appropriation ludique in the French original), resuming an idea developed decades earlier by Jacques Henriot (Henriot, 1983, 1989), a game theorist not widely disseminated in the non-French-speaking world, but of equal importance to better-known authors such as Johan Huizinga (Huizinga, 1990) and Roger Caillois (Caillois, 1967), at least concerning the study of the playful aspects of human relationships. This concept - ludic (or playful) appropriation - will be central to the development of this work, as will be seen later on.

Based on such preliminary notes, this work intends explicitly to discuss the relationships between ludic appropriation and the production of meaning in video games, seeking to understand how players can produce meanings when interacting with a particular game, exploring actions that were not designed or foreseen by its developers, adding new meanings to the videoludic experience. In addition to the theoretical approach, we analyze an episode of ludic appropriation by the community of players of Halo: Combat Evolved (Bungie, 2001), seeking to exemplify, from a real case, the concepts worked throughout the text. The episode became known as the Tower-To-Tower Challenge and involved a whole community of Halo: CE players. For instance, the video showing the accomplishment of the challenge has, as of July 2023, more than 230 thousand views and more than 500 comments, which points to the importance of the event, at least within a part of the community of Halo: CE players5. Thus, among the reasons for choosing this game as the corpus of analysis is i) the available documentation of the several attempts of beating the challenge - i.e., the ludic appropriation per se - in forums and YouTube videos; ii) the involvement of the community of players of Halo: CE in experimenting this particular ludic appropriation; iii) the shared experience of the ludic appropriation, via online conversational spaces, in forums and YouTube comments.

For the development of the arguments presented throughout the text, this work will dialogue with classic authors of game studies, such as Johan Huizinga, Roger Caillois, and especially Jacques Henriot, in addition to Maude Bonenfant6. Thus, a somewhat unprecedented contribution is expected to the current field of game studies in particular and media studies in general, as it advances in epistemological discussions about the constituent elements of games and their insertion in the contemporary new media context.

2. Returning to the classics: the notion of play in Huizinga and Henriot

Johan Huizinga, a Dutch historian recognized for his works on medieval history, defines the game as

(Huizinga, 1990).“[...] a free activity, consciously taken as "non-serious" and outside of ordinary life, but at the same time able to absorb the player intensely and totally. It is an activity disconnected from any and all material interests, with which no profit can be obtained, practiced within its own spatial and temporal limits, according to a certain order and certain rules”

For the scope of this work, we highlight three ideas present in Huizinga's quotation. First, the fact that the game is "external to ordinary life"; second, the fact that the game is played "within its own spatial and temporal limits"; and finally, the fact that the game is played "according to a certain order and certain rules."

The first idea that we take from Huizinga's quote, that the game is an activity apart from ordinary life, leads us directly to the notion of the game as a ludic activity, in the essential sense of this term, which is related to inlusio, illludere or inludere, to imagine, to illude. For Huizinga, playing is, above all, building a framework - we could say cognitive - in relation to the world, in which the player - when starting his ludic activity - assumes a role of suspending the usual rules of everyday life to engage in another scope of rules specific to such activity. That is, a lusory attitude is necessary - a term already explored by some authors, among them Bernard Suits (Suits, 1990) and Jacques Henriot (Henriot, 1983)7 - a posture that is capable of accepting the rules of the game as normal parameters and subject to acceptance, even if such rules, random as they may be, do not make sense outside the "game world," or, in Huizinga's words, in the "normal world." In a Karate fight (kumite), for example, athletes are not allowed to hit their opponents in certain parts of the body, such as the genital regions. On the other hand, if the same fighters were in a situation of confrontation in the "normal world," they would probably not follow this rule since, in this case, the objective would be to take down the opponent most efficiently as possible. However, within the martial art Karate, such athletes must assume a certain lusory attitude, building a new framework on how a fight between two opponents works, in which hitting the other in certain parts will result in disqualification. In the words of Jacques Henriot,

(Henriot, 1983)8.“To play, one must enter the game. To enter the game, one must know that it is a game. Therefore, there is a preliminary understanding of the meaning of the game on the part of those who lend themselves to play. The lusory attitude, like every attitude, is adopted. Like every attitude, it is understood”

We understand, therefore, a lusory attitude, as already elaborated by Ferreira and Falcão (Ferreira & Falcão, 2016), as a set of cognitive devices - cognitive framework - which the player must take ownership of so that she can enter the game in an appropriate, playful way, thus reinforcing Henriot's statement. A simple slip towards the "non-playful attitude" and the game could be interrupted or suspended, either by the players themselves or by those who seek to keep the game within such limits (referees, as in football) or even by the audience, which may call for intervention so that the activity returns to its ludic nature. Making an analogy to the fairy tale, the classic epithet of the inludere universe - playful, imaginative - it is as if, when telling a fantastic story to a group of children, the storyteller breaks the spell - abandons the playful attitude - by indicating, for example, that Rumpelstiltskin was nothing more than a popular fictional character that originated more than four thousand years ago and that had already been interpreted by several writers and that his magical powers were nothing more than pure fiction for the entertainment of the population. We could even draw a parallel between the idea of a playful attitude and that of suspension of disbelief, which is essential to narrative studies. As asserted by Marie-Laure Ryan about this parallel:

(Ryan, 2001).“[…] it is implicit to Coleridge's characterization of the attitude of poetry readers as a 'willing suspension of disbelief' (Biographia Literaria, 169), and it has been invoked by other thinkers, including Susanne K. Langer and John Searle […]”

In this case, the difference between the two notions would lie in the fact that while in the latter, this "disbelief" would be in the elements present in a given narrative, in the former, it would be in the constitution of the rules of a given game.

The elaboration of the first excerpt of Huizinga's quote leads us directly to the second excerpt, one that states that every game takes place "within certain spatial and temporal limits of its own," to which Huizinga names the magic circle, a concept that has already been much discussed in the context of game studies (Arsenault, 2005; Ferreira & Falcão, 2016; Salen & Zimmerman, 2003) and which refers to alleged temporal and spatial boundaries that must be taken into account when participating in a given game. In other words, every game occurs in a physically delimited space (geographically) and within a specific temporality (beginning and ending). Within these space-time limits, only and exclusively, the game's rules are valid. Outside these limits, the rules of the "normal world" apply. In a particular boxing match, for example, if one of the athletes strikes a blow before the start of the match (or a round) or after its end, this blow will be understood as aggression and not as something that is part of the sport of boxing (temporal demarcation); moreover, if one of the athletes leaves the combat ring for whatever reason, it is not valid for the other athlete to do so and both continue the combat in that place (spatial demarcation). In this way, the magic circle would spatially and temporally restrict the need to maintain the playful attitude discussed above9.

The third excerpt from Huizinga's quotation, the one that states that the game must be played "according to a certain order and certain rules," would perhaps encompass one of the most central and essential elements in the study of games, that is, the analysis of their rules and their implications on its entire ludic universe, an element already worked on by authors such as Roger Caillois (Caillois, 1967), Salen and Zimmerman (Salen & Zimmerman, 2003), Jesper Juul (Juul, 2005) and, once again, Jacques Henriot (Henriot, 1983).

Jesper Juul (Juul, 2005) states that most games are composed of two essential elements: rules and fiction. While the latter may or may not appear in a game - let's take the game of checkers, for example, in which no fictional component is present - no game can exist without it being composed of specific rules. These are the rules that shape - which characterize - a given game. For example, if a person were asked to describe the game of checkers, this description would probably fall, in the foreground, in its rules: "Checkers is a game composed of 24 round pieces, 12 of one color, 12 of another. The pieces are placed on a board formed by 64 modules/squares with alternating colors, usually dark and light. The game's objective is to eliminate the opponent's pieces", and so on. Its creator determines the game's rules, which should not, in principle, be changed so that the essence of the game itself is not changed.

On the other hand, some games may bring fictional content, such as chess, in which the pieces are distinguished by representations of "real" life elements, such as knights, rooks, and kings. However, in this case, the specific representation is not of fundamental importance, as another representation, such as characters from Star Wars or The Simpsons television series, can replace each piece. Thus, according to Juul (Juul, 2005), rules are fundamental and essential elements in any game, while fictional content is optional. Concerning video games, it is pervasive that, for the most part, they have fictional content to a greater or lesser extent. Salen and Zimmerman (Salen & Zimmerman, 2003), when addressing the rules of the game, state:

(Salen & Zimmerman, 2003).“Playing a game is following its rules. Rules are one of the essential qualities of games: every game has a set of rules. Conversely, every set of rules defines a game. Rules are the formal structure of a game, the fixed set of abstract guidelines describing how a game system functions”

In this way, we can say that every game is composed of rules and that these rules define - what distinguishes - a particular game from another. If we take the previous example, the game of chess, in three versions: its classic version, with pieces shaped like pawns, knights, and rooks; its Star Wars version and its The Simpsons version, despite the visual and symbolic differences of their pieces, it is possible to clearly say that all three versions comprise the game of chess. What allows this statement to be possible are precisely the rules of the game, which will be the same in all three versions and which will be explained through crucial elements of this game: a board with 64 squares, with alternating colors; 16 pieces for each player; pieces that move in a certain way, and so on. In the words of Maude Bonenfant,

(Bonenfant, 2015)10."We thus recognize, for example, the game of chess, making a precise list of its rules. This is valid for every game, even if, in some cases, we cannot establish a precise list of its rules"

Now, let’s suppose the rules are the essential element for structuring a specific game, giving it its "ontological" characteristics, which will create possibilities of action for the players. In that case, it seems to us, at first sight, that the rules of a game restrict and delimit the players' creative, inventive, and experiential capacities. As already pointed out by Juul: "Game rules are paradoxical: Rules and enjoyment may sound like quite different things, but rules are the most consistent source of player enjoyment in games" (Juul, 2005). On the other hand, a game without rules would become chaotic, causing it to lose its characteristics, as these would change incessantly. As Henriot states: "If, at every moment, each player had the right to do whatever he wanted, the game would lose its consistency" (Henriot, 1983)11.

This situation seems, at first glance, a paradox: every game must have its unambiguous rules, based on which the players will elaborate their actions; on the other hand, if the rules were completely determinative and prescriptive, there would be no room for player freedom, with the result that all matches of a given game would be the same, no matter if played by player A or player B. What form does the player's freedom operate in? To discuss this issue, we bring up the studies of games developed by Jacques Henriot, especially in his works Le jeu (Henriot, 1983) and Sous couleur du jouer (Henriot, 1989).

3. Playability of play and ludic freedom

In his book Le jeu (Henriot, 1983), Henriot introduces us to the notion that games are composed of rules, an idea already widely developed by other authors, such as Huizinga (Huizinga, 1990), Caillois (Caillois, 1967), Juul (Juul, 2005), among others. However, Henriot contributes to this discussion by presenting the rules working in two ways, which would function, in a way, as categories for a better understanding of their relationship with the game. It is what the author means by games with codified (or strict) rules and games [with rules] not expressly codified (Henriot, 1983). The first category would be related to the rules as a founding element of the structure of a game, its composition, and its particular definition. In the author's words: "Not only do the rules allow you to define and identify the game, but they are precisely what constitutes it: the game is nothing outside its rules. If they were modified, it would be different: it would be another game" (Henriot, 1983)12. On the other hand, pari passu with the codified rules of a game, there are the rules that are in turn appropriated by the players - games [with rules] not expressly codified - when they start playing, giving life to the codified rules, thus creating "[...] events from a structure" (Henriot, 1983)13. In the words of Henriot:

(Henriot, 1983)14.“In a game, everything remains the same: in this sense, every game is a system, but a system in which the elements are ordered within a duration. Taken as a structural formation, it is defined as a set of possible operations. It refers, therefore, even though it is nothing more than a structure, to the action of possible operators. It is intended for development as an "anything" that must begin, develop in different episodes, come to an end. On the theoretical level, it appears as a structure, but an organized structure distributed over time, an ordered process”

We can understand, therefore, from Henriot's thought, the game as something possessing a structure, which defines it as a determined game and which prescribes possibilities of action, but, at the same time, a structure that is not entirely closed, crystallized, which will then be "played" by individuals (players) over a period of time (magic circle), who will appropriate this structure to create something new, from their repertoire/experience as players (Bonenfant, 2015), giving it their meanings.

As some authors have pointed out, players make meaning from a game by interacting with its rules (Juul, 2005; Salen & Zimmerman, 2003). However, despite possessing unequivocal rules (Huizinga, 1990), games still provide space for freedom of action for their players. The fixed rules (their codifications, in Henriot's words) are then appropriated by the players, who will work on the (flexible) rules, possessing a certain space for creation. This is Henriot's concept of the "playability of play" (jeu du jeu). Bringing up the metaphor of parts of a mechanism, Henriot (Henriot, 1983) points out that there is playability when there is space for movement between the components of a certain mechanism. Thus, for Henriot, for there to be playability - that is, for a game (object) to actually be played - it is necessary that there be space for creative action for the player within its structural rules. Without this space, the game would become a simple performance of actions prescribed by its rules; on the other hand, a game with infinite space of movement would cease to be a game, as it equals any other human experience. Maude Bonenfant designates the term ludic freedom to this space of movement and creative action. In her words: "Without ludic freedom, the player no longer plays: he performs a sequence of actions in which the meaning is defined a priori" (Bonenfant, 2015)15. And she adds: "The game is necessarily based on a freedom allowed to the player, that is, to have a role in updating the game" (Bonenfant, 2015)16.

This space of movement - this ludic freedom - is directly associated with the possibility of creation within limits prescribed by the game's rules, making the playful experience of one player different from that of another. Otherwise, all game sessions would be identical, making such a standardized experience, at least in its materiality, in its cybertextuality (Aarseth, 1997). In other words: without ludic freedom, the actions seen on the screen during a game would be the same, regardless of the interactions performed by player A, B, C, etc.; such players would only act as "triggers" of actions prescribed and standardized by the game system. On the other hand, faced with an "infinite" ludic freedom, any game would lose its characteristics, as its rules would no longer function as a restrictive element of the possibilities for action by the players, making any game a playground in which any action would be possible. In this way, we understand ludic freedom - based on Henriot and Bonenfant - as a game space that is located between two poles: on the one hand, there is no freedom for creative action, in which the player would act only as a trigger of actions prescribed by the game; on the other, total freedom for creative action, a real playground/sandbox in which the player could perform any action - endless possibilities. In Henriot's words:

(Henriot, 1983)17."Acting in any way is not gambling; applying an infallible recipe, executing a program devoid of all alea is not playing either. The game is held at the equidistance between blind luck and the purest calculation"

We can therefore understand - based on Henriot's concept of ludic freedom - that games can be located within a gradient spectrum between those that provide less freedom to the player and those that offer greater freedom to the player, with the terminal poles of this gradient being situations of no freedom and all freedom. This understanding brings us closer to the concepts of ludus and paidia in the classification of games proposed by Roger Caillois (Caillois, 1967), a classification widely used in theoretical works within the scope of game studies. According to Caillois, ludus would designate the game played in consonance with the limits set by its constituent rules, by its structure; paidia, on the other hand, would be closer to a ludic activity less delimited by fixed and immutable rules, which Caillois designates as a principle "[...] common to fun, turbulence, free improvisation, and carefree joy" (Caillois, 1967)18.

In this way, we can think of ludic freedom within this interval between ludus and paidia as a process of negotiation (or mediation) between the game - understood here as a system of rules and prescriptions - and the player - who will be able to apprehend the game system, its rules, to produce emergent actions within the game world. Maude Bonenfant calls this movement ludic appropriation (appropriation ludique). In her words: "If the game is based on rules that are intended to be fixed, it is, however, always updated in a different way by the player who experiences it, giving rise to new meanings" (Bonenfant, 2015)19. In other words, appropriating (in a ludic sense) a game consists of apprehending its rules and performing emergent actions endowed with meaning, which will differ from player to player. For this to be possible, the game must provide a certain ludic freedom - it must have play (jeu), in the words of Henriot (Henriot, 1983). This ludic freedom should ideally not lean towards either of the two poles of the spectrum delimited on the one hand by ludus, on the other by paidia: should it leans towards one side, the player will be reduced to a performer of completely foreseen and prescribed actions, without no power of creation on her part; should it leans to the other side and complete freedom - the complete absence of rules - will empty the player of the lusory attitude necessary for the adequate performance of the ludic activity. As Bonenfant concludes: "To play is to appropriate the game, that is, to create a distance that allows an interpretative freedom of its rules and its results, even if the creation of this distance encounters limitations" (Bonenfant, 2015)20.

4. Skills, appropriation space, and ludic appropriation

As we have been developing throughout the text, a close relationship exists between the conditions of emergent actions provided by a given game and the player's freedom to produce new meanings. Based on this premise, I propose another relationship that can also be verified in games - if not in all games, at least in part of this universe: the relationship between the player's skills in a given game and the degree of possibilities for carrying out emergent actions, and production of new meanings, by the same player, in the same game. This relationship is closely linked to the structuring rules of the game, as well as to the possibilities of results emerging from the interaction with such rules. As Juul (Juul, 2005) points out, games of emergence are those that, based on a limited number of rules, provide an almost infinite number of results (outcomes) and different game sessions (matches) based on the possibilities of arrangements made by the players, from the interaction with the rules of the game. A clear example of this type of game is football (and most traditional sports). From a limited number of rules, each game session (match) will differ from another due to the immense capacity of possible combinations of actions within the game rules. No wonder the degree of replayability in traditional sports tends to infinity. In the words of Juul: "In chess, you win by checkingmating your opponent - but there is a myriad of end positions in chess that qualify as checkmate, and each of these positions can be reached in an immense number of different ways" (Juul, 2005).

However, for these possibilities to be explored, it is also necessary that the player has skills in a given game. Returning to the example of the game of chess, pointed out by Juul, if we have a game between two novice players, inexperienced and with few skills, the tendency is that the space for creating emerging actions on the part of these players is small and that there is little variability in game sessions, as they will possibly tend to act within their small "inventory" of actions. On the other hand, in a match between two professional players, the tendency is for more significant variability in the game sessions since the players will have greater possibilities of action since their inventory will also be more extensive. Maude Bonenfant calls this inventory the "player's encyclopedia." In her words:

(Bonenfant, 2015)21."Thus, the [player's] encyclopedia encompasses the player's resources to produce meaning and also to perform a meaningful action. It is, therefore, a key factor in refreshing the game"

At this point, we arrive at the idea of ludic appropriation - or appropriation space - as presented by Maude Bonenfant (Bonenfant, 2015). According to the author, this space refers to the player's freedom of interpretation and creative action when interacting with a given game, which is not necessarily restricted to the game's prescriptions, that is, to what the game ideally expects the player to do. In fact, we could expand the concept of appropriation space beyond the domain of games, understanding it as an interpretative framework of the world - a mode of production of meaning - from the individual's point of view. In Bonenfant's words:

(Bonenfant, 2015)22.“The space of appropriation is, in fact, a more or less creative space for the individual to interpret the world to adapt it to her perspective. In the appropriation space, the mediation process develops: the world is interpreted from the individual's point of view”

Thus, we understand ludic appropriation as the act of twisting the prescriptions of a given game to produce new experiences and meanings based on the peculiarities of the players, regardless of the game’s proposed objectives. Bonenfant says about the space of appropriation: "It is the space of freedom necessary for the player to appropriate the game, make it hers and for her [the player] to become the creator of her own ludic experience." She continues: "The appropriation allows the player to singularize the interpretation of her ludic experience. Within the rules, there is the fluctuation of interpretation: the (mechanical) plays of the game" (Bonenfant, 2015)23.

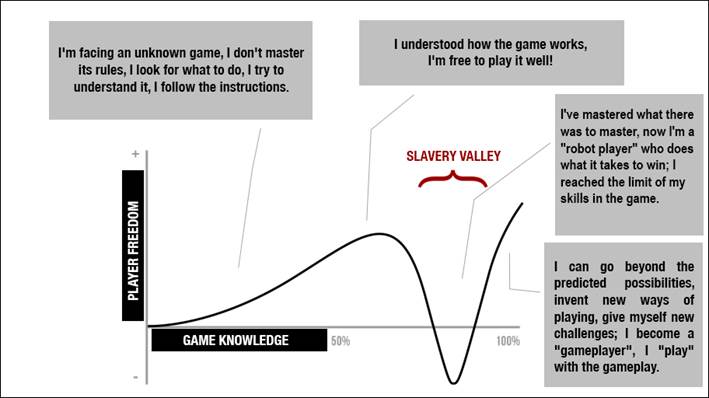

The graph in Figure 2 seeks to illustrate the process carried out by the player from the beginning of the interaction with a given game until she enters the so-called appropriation space: as her knowledge of the game increases, her ludic freedom increases, until it reaches the point where all creative possibilities will have been exhausted ("slavery valley"). Then, new opportunities for creating innovative and meaningful actions within the game open up - to beat the device, in the words of Flusser (Flusser, 1985) - from the ludic appropriation process (Bonenfant, 2015).

Appropriating a game is, therefore, taking the game for oneself, seeking to apprehend new forms of action within its constitutive (codified) rules, regardless of whether these forms approach or distance themselves from the objectives initially proposed by the game, thus producing new meanings, which may or may not be shared.

5. Ludic appropriation in Halo: Combat Evolved

Returning to the example cited at the beginning of this article, which refers to the ludic appropriation in Halo: Combat Evolved (Halo: CE), we can list some propositions regarding the action prescriptions suggested by the game as a structure of rules and possibilities of action on the part of the players.

Halo: CE is a first-person shooter (FPS) in which the player controls the main character, Master Chief, a human "improved" in his physical capabilities and abilities. With a science fiction theme and framed in what Juul calls a game of progression, in Halo: CE, Master Chief must go through a significant expansion of its virtual world - set on the ring planet called Installation 04 - fighting alien beings known as the Covenant, avoiding being hit by them. Master Chief has an energy shield - provided by his MJOLNIR armor - that absorbs damage caused by the Covenant weapons. If the shield level reaches zero, the Master Chief will be completely exposed, and any subsequent damage will lead to his death.

During his campaign, Master Chief must follow a "correct" and sequential path to reach the final objective: to activate the detonation of Installation 04 and flee from it, thus extinguishing the Covenant and the Flood - another species present in the game, which acts against all sentient lifeforms, including the Covenant. It is, therefore, a game in which the possibilities of exploring the world are reduced when compared, for example, to open-world games (sandbox), such as Red Dead Redemption (2010) or The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015), in which the player has at his disposal the exploration of the entire world (map) of the game, with no "correct" path to be chased. In Halo, after Master Chief moves to another part of the game world, it is impossible to return to the previous position, thus characterizing spatially disconnected areas in terms of access.

Regarding the concept of cybertextuality, as proposed by Aarseth (1997), Halo: CE works as a cybertext in which the player must choose between possible paths to be followed, and in this case, only one of the options will be the "best option" - correct option - to achieve the objectives proposed by the game. In fact, there are no possibilities of "wrong" paths: the most that can happen is for the player not to find the right direction and to be stagnant in the game's progression without advancement. In this sense, there is no way for the player to be successful without taking the only correct path, the one designed by its developers. In other words: in Halo: CE, the player has no choice but to follow the path programmed by its creators. Other options would be, for example, not advancing in the game, such as being stuck in a part of the world. However, in this hypothetical case, the lusory attitude necessary for the game to unfold properly - as designed - would be largely lost, in addition to causing the game's narrative not to advance. In short, the player must follow the correct path, performing proper actions - effectively to achieve their goals, considering that the player is imbued with a lusory attitude and wants to remain in the game flow.25

Since Halo: CE is a game strongly based on progression (linear, in this case), there are limited action options to follow the correct path and overcome the proposed obstacles. This assertion can be proven, to a certain extent, when searching for game walkthrough26 videos on platforms such as YouTube. For example, a large part of the videos will show a player explaining how to move forward in the game space in the "correct" way, in addition to giving tips and clues on how to advance without suffering damage, that is, seeking maximum efficiency so that the player can achieve her objectives. If it were an open-world game, the number of videos - players performing their actions differently - would be much more significant since the possibilities of achieving the objectives would be equally multiplied.

How, then, to balance this equation when the whole functioning of a game has already been discovered, opened, and unveiled? When the "black box" has already been densely searched and scrutinized - returning here to Flusser's thought (Flusser, 1985) - and there is nothing new to be created?

Taking this specific example, i.e., the Tower-to-Tower challenge in Halo: Combat Evolved, we can make the relationship between ludic appropriation and production of meaning: having nothing more to discover within the prescriptions set by the game in its structure of rules, players use their abilities - from their encyclopedia - to create new objectives in the same game within its system of rules; objectives that have nothing to do with the "ideal game," the one foreseen by its developers, but which open up a range of new possibilities for interaction, new aesthetic experiences, new productions of meaning. Jumping from one tower to another, in the Halo level of Halo: CE foresees a high level of skill on the part of the players, great experience with video games in general, and, above all, creative inventiveness: to accomplish this feat, players of the Halo community discovered that by placing grenades below the Warthog vehicle it would be thrown into the air, to the point that it could fall on one of the towers. If, in addition, the Master Chief jumped on top of the vehicle between the interval of the grenade activation and its detonation, not only would the vehicle be thrown, but also Master Chief himself, causing both to fall on the first tower. Then it would be necessary to repeat the procedure, but this time on the first tower, precisely calculating the throwing angle so that Chief could land on the second tower alive. According to reports from community members who accompanied the attempts to carry out the undertaking, just the setup of the procedure lasted around a few hours, while the procedure itself took a few seconds.

Between 2004 and 2011, several attempts to beat the challenge were performed. The first one occurred on September 19th, 2004, nine days after the challenge's announcement. In this attempt, they managed to take Master Chief (alive) to the first tower, but they couldn’t land on the second tower, falling on the ground and killing Master Chief. As stated by Duelies:

27. Also, according to Duelies, it was only on October 15th, 2005, that the player and community member BlueDevil managed to land on the second tower, but with a dead Master Chief. Since then, many players and community members attempted to beat the challenge. Most of them managed to get Master Chief to the second tower but failed to keep him alive, which was the main goal of the challenge. Several of those attempts were compiled in the aforementioned Duelies video. By 2011, according to Duelies, many players had given up the challenge, “convinced that it was impossible,” and as of June 2011, it became a competition between players Boofass and Duelies to see who could finish the challenge first. Eventually, on June 4th, 2011, Duelies finally completed the Tower-To-Tower Challenge.“The challenge was deemed impossible, and most wouldn’t even dare do try. Those that did try couldn’t even come close [to beat the challenge]”

The achievement of the challenge was responsible for producing new meanings and experiences for the community and fans of the Halo franchise, including spectators of the entire challenge process - in the end, Duelies edited a video of more than 10 minutes, telling the whole story and the whole process of the jump, the failed attempts - his and other players - and finally, as in a cinematic climax, the completion of the challenge. Performance, skill, and subversion of the rules stipulated a priori in favor of broadening the experience with that medium.

6. Final Thoughts

In theoretical and epistemological terms, there is still much to be explored about the relationship between the act of playing and the various possible ludic explorations in this act. The case study discussed in this paper, i.e., the Tower-To-Tower Challenge in Halo: Combat Evolved, is only one great example of the ludic appropriation performed by video game players. Indeed, there are other examples to be discussed and analyzed. Furthermore, as a result of this work, I believe it is possible to advance, for instance, in the investigation of the relationship between the ludic and the aesthetic experience within the epistemological bias of pragmatism theorists, such as John Dewey (Dewey, 1980) and Richard Shusterman (Shusterman, 1998), especially regarding players appropriation experiences, a challenge that I place right now on the horizon of my academic investigations.