It is well known the deep relation between the Portuguese crown and the Military Orders along the medieval period. In the background of the Iberian reconquest (Reconquista) the Military Orders had assured relevant military services, contributing to the achievement of the papal objectives, as well as the royal ones. Indeed, their own objectives either in the religious perspective or in the jurisdictional field, were relevant in this context. These commitments had a great impact on the territorial sphere. A lot of lands and castles were given to the Military Orders to assure their services and loyalty (COSTA, 2015, p. 12). As result, the mutual interests were in evidence. The friars were a part of a structure and they should be able to keep their organization as a military corpus, their weapons, horses, castles and walls well equipped, preserved and in proper conditions. Therefore, the relation between the Military Orders and the Portuguese Kings became more complex within the territorial expansion throughout the Southlands, and throughout the overseas horizons (as well as in Mediterranean Sea and in North and South Atlantic Ocean).

Considering this framework, we intend to discuss the war organization performed by the Portuguese crown and the Military Orders. Actually they constitute two elements of a single issue, because there was not any permanent or professional royal army, skilled to a successful autonomous activity. Both, the King and the Military Orders, were dependent on the recruitment of some external people. The most important representatives were from the nobility, at least in an ancient time, and from the municipal militias. Although, this is a very important issue, it is quite impossible to estimate the numbers of the men-at-arms, namely of those who were recruited by the Military Orders.

According to some bibliographical data, it is possible to point out some examples from the participation of the religious knights within the royal armies. Since the Military Orders in Portugal were a kind of branches from international organizations, it seems very significant the constitution profile of the armies that they must mobilize in the Latin East territories and in some other kingdoms closer to Portugal. For example, in the battle of La Forbie, in 1244, was involved an army constituted by the knights of the Orders and from other knights, although it is not possible to confirm the origin of some of them. Some numbers are known that put in evidence the complexity of this issue: 312 Templar knights and 324 turcopoles; 328 Hospitallers knights and 200 turcopoles; 400 Teutonic friars; and 600 knights from the Cyprus and Jerusalem kingdoms (CLAVERIE, 2009, p. 364). A second example, also from the Latin East, is about the Saphet Castle, where there were 2200 men commanded by the Templars, which only 50 were friar knights, suggesting their ability to mobilize some civilian groups (CONTAMINE, 1996, p. 115). In the opposite side of the Mediterranean, the Iberian Peninsula was also a special territory for a similar process of religious and cultural war. The written memory already known on the siege of Seville, from 1248, reveals the participation of 150 to 200 friars commanded by the Military Orders, among around a total of 700 fighters, because each friar should be accompanied by a mounted squire and by 2 or 3 men from the infantry. This force represented 5-6% of the royal army (MONTEIRO, 2012, p. 847-489).

In Portugal, we also find some examples among the documental sources regarding the participation of the Military Orders within the royal armies. In the emblematic siege of Alcácer do Sal, in 1217, around 500 men were under the leadership of the Templar Master (MARTINS, 2014, p. 194). Of course, only a few part of them would be Templars. Although, the medieval war was above all a siege war, being avoid the conflict in open battlefield, the recruitment operations were equally decisive. The defensive tasks were always a priority, not only regarding the Muslims, but also the Christian enemies, namely when they were in front of the diplomatic border line. In 1295, within the Portuguese participation in the Castilian internal political conflicts (1284-1295), the Templars had some difficulties in mobilizing military forces from Tomar, the main house of the friars in Portugal, to Touro, a close village under their jurisdiction1. The military performance of the Orders was not dependent exclusively on their own friars. The success of the operations expressed as well the involvement of other people, who obeyed to the Order. Therefore, the articulation between the Military Orders and the municipal militias, concerning joint armies, formed by non-noble knights (the so called «cavaleiros-vilãos»), was determinant, although it could arise some difficulties related the recognition of authorities.

Summing up a global projection of the Military Orders armies remains difficult, because the documental sources are not clear on this issue. Only a complex scientific research can renovate the knowledge on this topic, especially on the Portuguese late medieval ages2. At least, with the available evidence, a first projection was already pointed out. Considering the Master, his personal defensive group composed by 6-10 knights, and some friars who served in the convent of each Order, in the castles and in the several commandries, the number could be around 150 friars devoted to military tasks. According to the PhD thesis of Miguel Gomes Martins, the Orders of Temple, of Christ, and of Saint James could have 40-50 friars each one; with a less significant number, the Orders of Saint John and Avis seemed only assured 30 friars each one (MARTINS, 2014)3. It is difficult to subscribe these numbers and only a wide research can provide a better understanding of these contingents. Without answering to this specific challenge, the Ordinances from the 1320s defined the number of the different categories of friars, including the knights.

Table 1 Military Order's Ordinances

| Military Order's Ordinances | ||||||

| Order of Christ | Order of Saint James | Order of Avis | ||||

| Year | 1319 | 1327 | 1327 | 1326 | 1327 | 1327 |

| Knights | 71 | 69 | 66 | 71 | 61 | 51 |

| Clergymen | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | ? | ? |

| Servants | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ? | ? |

| Total | 86 | 84 | 80 | 86 | >61 | >51 |

Sources: LENCART, 2016, p. 99-132; MARTINS, 2018, p. 321-336.

When King João I became the first monarch of the second Portuguese dynasty, in 1385, he understood the importance of having a royal army. This man was not born to be a King, because he was not the oldest son of Pedro I. When he was a young boy, his father appointed him to the Avis Order, which option would be very important in his future political experience, when he became the king after an interregnum period. As a King, he was legitimized either by legal arguments and in the battlefield, proving to the Castilians, the political opponents, that he deserved indeed to be the King of Portugal. So, it is understandable the ordinance that he would enact, the so called «Hordenança certa», a kind of a modern requirement intending to a permanent royal army. Otherwise, in a difficult context, the King would be always a hostage from those who desired to be part of the army. In this ordinance, João I demanded the recruitment of 3200 «lanças» (men-at-arms). Among them, the King wanted to be served by 340 friars, recruited within the Military Orders (MONTEIRO, 1999, p. 269). Like what seems to be the balance between all of them, in this moment the Orders of Christ and of Saint James were responsible for most of the men-at-arms. Each one should provide 100 friars. Avis Order had to contribute with 80, and Saint John only with 60 friars. This last Order had a peculiar profile, which means a less commitment with the war, having a deep involvement in social and religious backgrounds, namely in the Iberia. In a different perspective, this institution along the late medieval times, was the most important Order that assumed the fight against the Ottomans in the Mediterranean war. These two arguments seem to explain the participation with a smaller number of «lanças». We do need to emphasise that these numbers represented only a royal recruitment project. Based on the documental evidence, it is impossible to assure the actual accomplishment of this project. The Military Orders armies were always integrated within the Royal army, providing some men-at-arms, horses and weapons.

In addition, the scientific knowledge supported by the documental evidence is based on municipalities’ charters («forais«), several royal documents and other ones related with the Orders, regarding the organization of their armies, and a special list of crossbowmen («besteiros do conto»).

The first typology, this means municipal charters, proved a strong commitment between the municipal community and its jurisdictional tutor. These documents could be enacted either by the King or by the Military Orders, or less often by the bishops. All of them open a complex set of core questions: Social privileges; social obligations; social peace; and taxation. Selecting only the ones that concern the war, both in a defensive and in an offensive perspective, becomes clear the role that the Military Orders were expected to play in war.

Regarding the social privileges, most of these charters included a statement that allowed a certain knight to keep his privileges, even if he would lose his horse or if he would get older and becoming enabled to fight. The horses’ knights were also protected. Those documents applied several penalties to whom who tried to steal them. Although the chivalry was the social elite within the Portuguese municipalities, the «forais» also focused the infantry. For instance, a man from the peonage could be promoted to chivalry if he could afford an amount of money to buy a horse. The recognition of this status was also foreseen to a clergyman, who would be treated as a knight concerning his houses and rural proprieties4. The history of the Portuguese territory until the end of the reconquest (1249-50) explains quite well this kind of social background, encouraging the involvement in the war.

In this context, the social obligations were also defined with some detail. Therefore, it was stated that 2/3 of the knights should participate in the offensive war («fossado»); and 1/3 should remain in the settlements to defend them5. If they did not attend this mandatory call, they should pay a penalty («fossadeira»). This kind of operations was indeed very important for all the agents who collaborated with the war and the in defence of the settlements of the kingdom. Regarding this subject, the citizens living in the Military Orders’ municipalities should have horses if they could afford them. The horses were always essential for these institutions that used them for the intervention in the Iberian and in the Mediterranean war scenarios and for traveling among their extensive properties. Not only the friars, neither the horses, were exclusively enough to succeed. The vassals of the citizens under the Military Orders’ jurisdiction should also serve the Orders’ structure with the same objectives.

This society, educated for the practice of the war, had to define internal pacification rules, expressed in the same manuscripts. Therefore, the use of weapons against someone in a day life scenario was punished with severe financial penalties6. Of course, this provision aims at promoting the social organization and a peaceful environment inside the municipal communities, at the same time it intends to collect revenues from the punishments.

The taxation was a primordial topic when the war was a priority. As already has been said, «fossado» was the military obligation concerning the offensive operations across the enemies’ territories. Whenever it occurred, 1/5 of the total collected loot should be given to the King, while in Tomar and Pombal the same amount should belong to the Templars7. This constitutes a relevant incentive for the Order. With a similar objective, it was allowed that a knight could keep for himself the first looted horse. However, the remaining ones should be given to the King.

From this theoretical and jurisdictional framework and being impossible to realize its concrete application in practice, some documental examples on the mobilization for the war become clearer. Side by side, Kings, masters, commanders and municipalities were either cooperators or rivals according to the circumstances. The equilibrium was always difficult, because they had to share common interests.

In the Portuguese archives there is some documents on the Templars’ suppression, even though this process in Portugal have had a peculiar profile quite distinct from that happened in France (COSTA, 2019). In this context, a royal inquiry aiming at collecting information, along 1314, contains arguments related with the friars’ involvement in the war8. This is a quite intentional text since it was produced with clear royal objectives. The answers given by the respondents in this survey pointed out some issues relating to this paper. To sum up the main questions, the men involved in this enquiry procedure had stated:

The Templars had always served the Portuguese Kings with their horses, weapons and men at their own expenses.

The municipalities and settlers who lived in villages and castles under the Templars’ jurisdiction would not serve with them in war, unless it was made by a special requirement from the King; the municipalities, even if they were under the Order’s jurisdiction, should only be submitted to the King.

If the King somehow called the Templars’ municipalities for his service, they should attend, and the friars should go with the King anywhere.

Considering the King’s former donations of heritage, the Order served the Crown with horses, weapons and with logistical support (bread, meat, barley and with many other things). All this service was performed under the Order’s expenses.

Whenever the Kings wanted or needed, they could captivate the Order’s castles and settlements, using their profits for crown’s service, and commanding the people who were living there.

As for the previous remark on the possible artificiality of the jurisdictional and legal texts, it must be noted that the selected above answers contain demagogical arguments. To achieve a better understanding on the mobilization for the war it is necessary to perform a wide research, considering different kinds of documents in order to try to complete a complex puzzle, which is the main objective of Leandro Ferreira PhD thesis focused on the late medieval period.

In the perspective of the masters facing the municipalities there are known several evidences proving the complexity of the recruitment process. Setúbal was an important municipality close to the banks of Sado river and close to Palmela, the main convent of Saint James Order in Portugal. Setúbal, in medieval times, was a rich village, providing benefits either to the King or to the Order (DRUMMOND, 1998). So, this municipality organized inside the settlement itself was very attractive. In 1341, there were conflicts between Saint James Order and the municipality. The Order was accused of obliging the municipal militias to participate in the war within its own army («em hoste e em fossado e fazer Guerra»)9. According to the municipality, its own militias should only serve with the Order under the condition of being ordered by the Master specifically to integrate the Royal host. Of course, the Crown was in accordance with this requirement. But the interpretation of it was not all consensual. The municipal officers said that the master and the convent of Saint James had obliged them to participate in host, that is to say «fossado» (offensive war), and into the war without the royal ordinance. Answering to this accusation, the master and the convent changed their initial position, what seems to be very relevant. From then on, they argued that they would only mobilize the municipal militias if it was ordered by a specific document enacted by the King. And then, only if the above condition was observed, the municipality should serve the King within the Order armies (MARQUES, 1997, p. 285-305).

The conflicts between Military Orders and the municipalities were common. Going back in time, in 1295, the Templars had complaint to the King about the Tomar municipality10. The citizens from this settlement had refused to integrate the mobilization of a military corpora specifically ordered to go to Touro village. Given that, and considering the Iberian political background, the King was interested in this contingent and in consequence he had agreed with the Order. This issue remained completely unsolved. King Afonso IV (1325-1357) had exempted the municipal militias to serve with the Order’s master and obliging them to integrate the Order’s armies when the King ordered them to. It should be underlined that the change of the political context supported the King’s decision of benefiting the municipalities and not the Order. In 1335, Afonso IV changed his position. He has accepted the arguments of the Order of Christ, authorizing the friars to mobilize the Municipal militias of Tomar, in accordance with the tradition of the Templars until 1295.

Also, at Longroiva, a municipality located at Beira, close to the Castilian’s border, the citizens refused to obey the call from the Order of Christ in 132411. The municipality stated that the citizens would only recognize the royal military calls. But King Dinis, conscientious about the importance of the frontier, ordered the municipal militias to follow the Order’s requirement. The Order of Christ, since its very beginning, was so close to this King, what can reinforce his decision. In 1325, it was made a copy of the judicial decision on this topic, which means that the problem was not completely solved12.

Around a century after and considering a distinct typology of information, we can add to the discussion a different documental example and enhance the problematization on the mobilization process. In 1442, a discharge letter («carta de quitação»), this means a receipt, contains the list of income and expenses played under the royal fiscal administration («almoxarifado») in Lamego, relating to the years 1434-1440. This document included expenses assumed by prince Henrique to support the officers and the armada against the African town of Tangier. Gonçalo Vasques Coutinho, commander-in-chief of the Order of Christ, received from the King a large amount of money to recruit 20 mounted men-at-arms and 30 infantry warriors to serve in the mentioned armada. With less importance, the same document offers information about another payment for this armada. Fernando Camelo, commander from Vila Cova (Order of Christ), received money to recruit 6 mounted men-at-arms and 10 infantry warriors13.

As it can be seen from the previous examples, besides the masters, also the commanders were requested to accomplish the military recruitment demands. Their actions have also created conflicts and misunderstandings with the municipal powers. The specific documented cases involve all the Orders, which is very significant for the study. In 1357, the representative of Oleiros municipality applied to the King Pedro I (1357-1367) against the commander of Saint John and against «alcaides» (the keepers of the castles) and «vedores das contias» (the supervisors of wealth issues), regarding the recruitment14. These officers evaluated and attributed the possession of some horses and weapons to some people without respecting the frame of the law, which defined a ratio between the number of people who lived in a municipality and the value that they could get. To reinforcing the arguments, they quoted the example of Cortiçada and Sertã. Facing the problem, the King decided that the law should be respected.

After the first Peninsular War (1369-70), in 1371, the representatives of the municipalities argued that Saint John, Christ, Avis and Saint James, as well as some other lords, being in the border territories, had exceeded their prerogatives, nominating a kind of captain for the knights and men from infantry («coudéis dos cavaleiros e peões») and supervisors of their wealth («acontiadores»)15. In consequence, some wealth was donated to some people who did not lived in the place in which they were evaluated. The situation was worrying, and they asked for the royal intervention. King Fernando ordered the high royal officers in local administration («corregedores») to verify the situation, and to respect the royal laws, that imposed that those men who possessed horses and weapons should live in the respective place where they have been evaluated.

The conflicts were not performed only by the masters and the municipalities. Other members of the Orders, like the commanders, were also involved themselves in these disputes. In 1432, the representatives of the municipality of Assumar complained to King João I (1385-1433) against the commander of Juromenha (Order of Avis)16. The commander was misconducting the recruitment tasks targeted on men to integrate the municipal militias. In other words, this officer obliged the local men to appear in the periodical weapon revisions («alardo»), and attributed them the obligation of buying horses, complete coat-of-arms, weapons and crossbows, even if they were exempted of having those duties. Preventing this bad evaluation, the King ordered that the previous privileges of exemption should be respected.

The mobilization of municipal citizens with war purposes was more complex and it did not resume the assembly of armies. As the medieval war was above all a siege war, and not a battlefield conflict, the maintenance of the territory and of the fortresses were crucial. The Military Orders held multiple castles in Portugal. The friars were not in enough number to do all the tasks involving the building and the repairing of the fortifications. They needed to assemble other forces to achieve those objectives. For example, in 1337, the municipality of Cabeça de Vide complained against the master of Avis17. According to the arguments of the municipality officers, the master had caused many prejudices over the settlers. They were obliged to serve during 6 weeks in Noudar, just on the borderline with Castile, to do building and repairing works in the walls of the fortress. However, the King forbade that service in Noudar, because those working tasks should be only sponsored by the Order.

Being aware of the strategic importance of the fortresses along the territory, Pedro I, in 1358, gave privileges to the keepers of the castles («alcaides»), and to the craftsmen who executed jobs related with naval construction («arrais» and «petintais»), from Setúbal, a village under Saint James jurisdiction18. Although this fortress was not on the land border, it was in front of the ocean, from where could appear any threats, and it also represented a symbolic manifestation of the power within the local community. The already mentioned men were exempted of having horses. In consequence, the king forbade the Master of Saint James, as well as the municipal officers, to force them to have horses against their desires and to be involved in the war campaigns. To conclude, this royal document authorized the Saint James Master to be the responsible for the recruitment of the municipal militias of Setúbal.

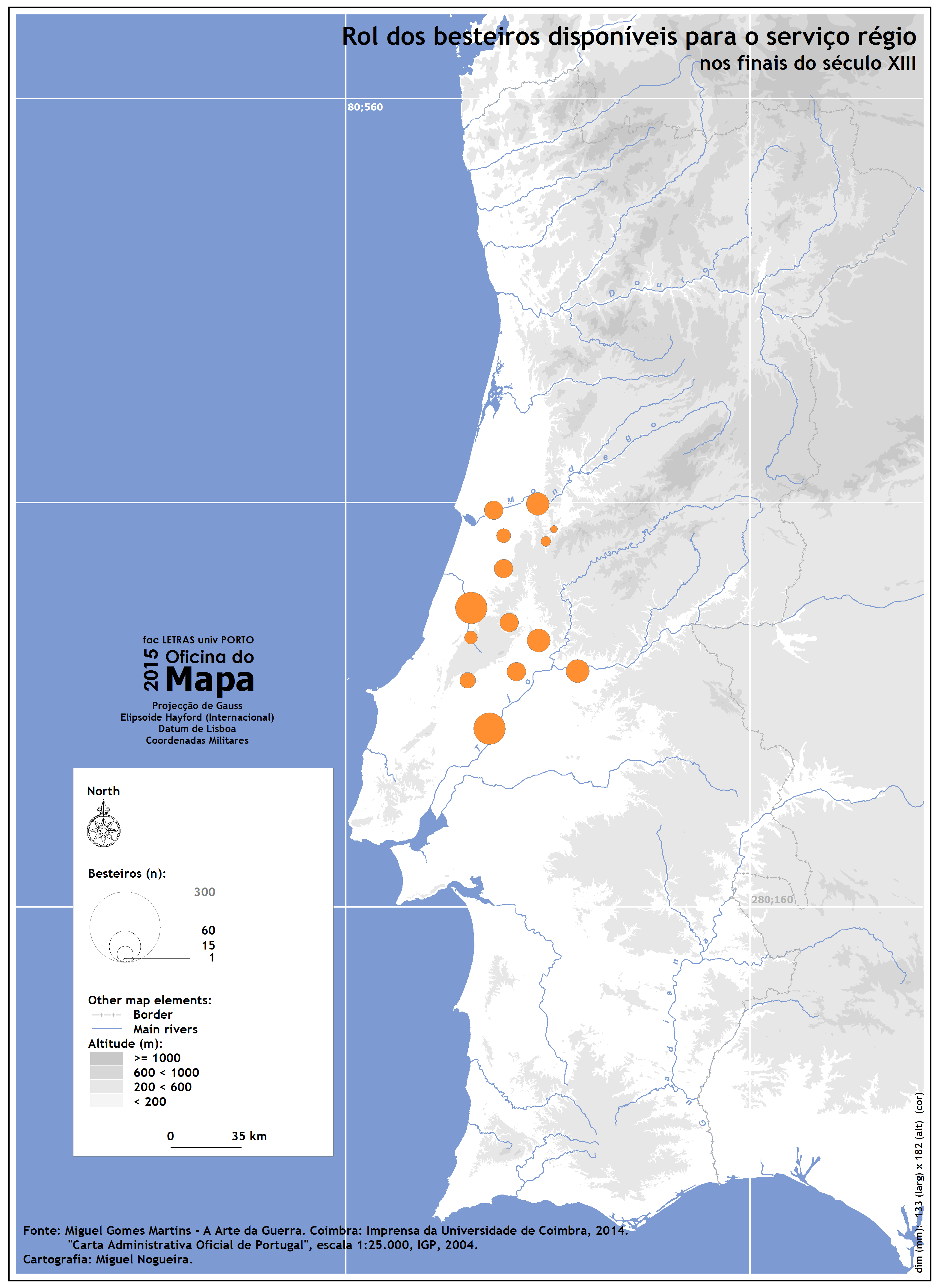

The Portuguese Kings had also issued other measures concerning all the kingdom, namely in a military perspective. Such as the castles planning distribution along the territory, gradually the Crown had assumed other options with the purpose of developing an integrated approach of the war, including after the end of the reconquest. The «besteiros do conto» (crossbowmen), created in 1299, are a good example (MARTINS, 1997, p. 93; FERREIRA, 2015). They constituted a corpus of armed people with a special and effective weapon - crossbow -, which militia had a specific number of warriors, requested by the Crown, and the municipalities were required to fulfil that certain number («conto»). Before the creation of this corpora, there was already a strong tradition of recruitment, within the municipalities, of similar groups of crossbowmen. However, its organization was not depending on a specific list or number given by the Crown. At the end of the 13th century, there were 338 crossbowmen. With the data we can collect from the manuscripts, it is impossible to know how they were distributed along the territory. The first documental source on this matter points out only to a special region between Coimbra and Lisboa. A part of this territory corresponds with an area where the Templars were strongly settled. Indeed, the Templars should recruit this military force in their own lands: Tomar (32 crossbowmen), Pombal (21) and Soure (12). Comparing with other villages with more population, like Coimbra, where it was recruited 31 crossbowmen, one can say that Tomar was much more militarized and committed, with the royal army.

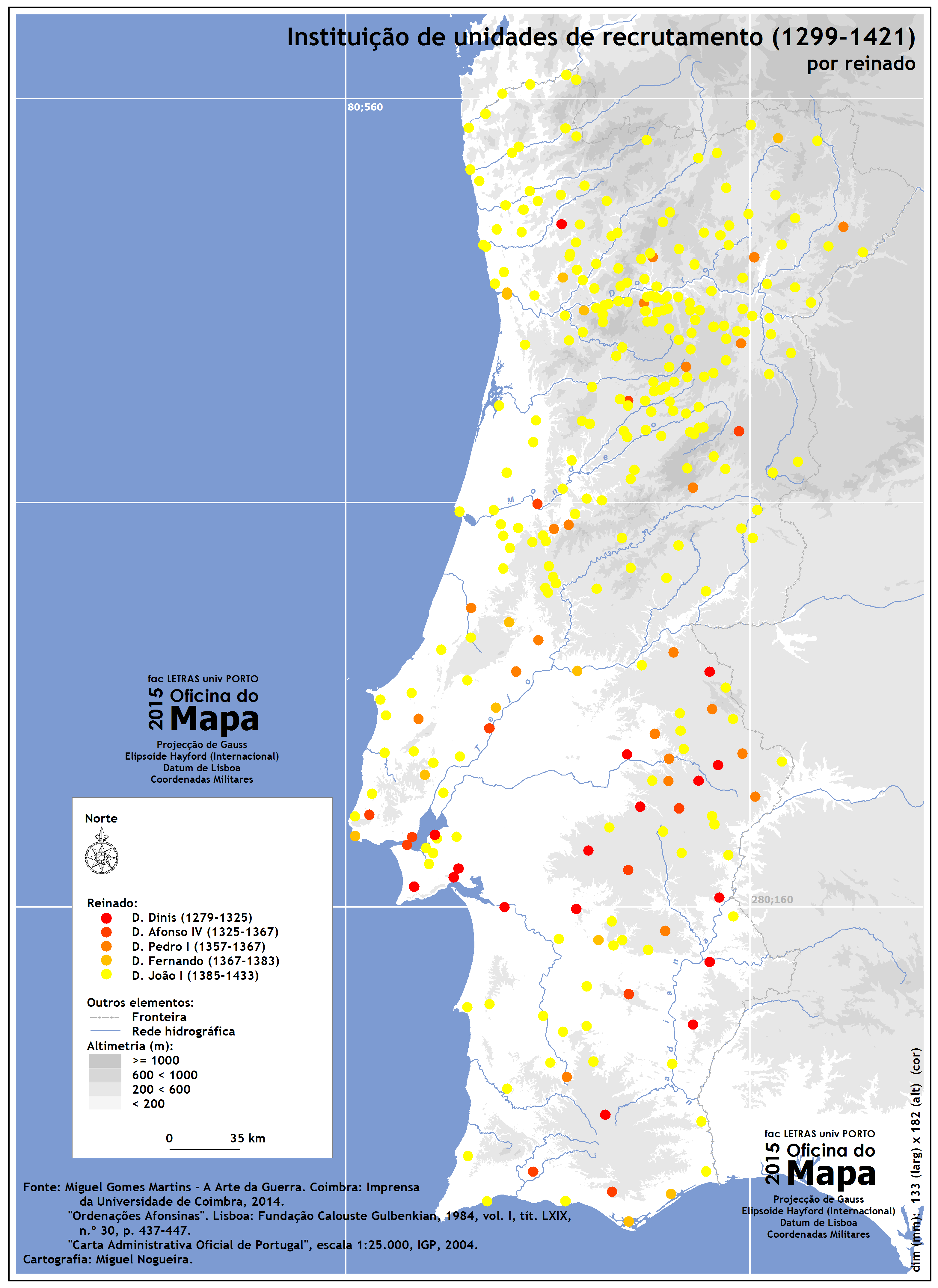

According to other manuscripts, until 1421, the «besteiros do conto» force was scattered throughout the entire kingdom. They were around 5.000 men. The initial priority of the Crown was focused on the South of Portugal (Alentejo), where the Military Orders’ settlements were intensive. The creation of the «besteiros do conto» was also a political measure to achieve the control of the military role of the Military Orders. Only in a second moment, during the second half of the fourteenth century and the fifteenth, the militia had significantly expanded to the North of Portugal. This is quite interesting within the gradually loss of the ancient prominence of the noble men at the war tasks. Many of these recruitment units were under Military Orders’ jurisdiction. This was a coincidence with royal objectives, since both were interested in improving the quantity and the quality of the military contingents (municipal militias were under-exploited after the end of the reconquest).

To conclude we want to highlight some final remarks. The documental evidence on the involvement of the Military Orders in the war matters demonstrates that the king and these institutions were both responsible for the recruitment and for the mobilization. It was indeed a difficult process which required mutual commitments. The known numbers for other countries reflect the same mutual military obligations, because the armies were always shared and not exclusively composed by Military Orders friars. The armies had a very small number of friars both in Iberia and in the Latin East. According to the scarcity of friars, the most expressive base of recruitment in Portugal was the municipal militias. However, Military Orders only had under their jurisdiction a small part of the municipalities. Administrating their territories, the friars somehow enacted municipal charters («forais»). These documents were used to shape the governance model of the territory, and some of the most important clausula are about military procedures. However, the municipalities accused either the masters or the commanders of acting in their own interests and against the local ones. On the other hand, the Crown did not assume a coherent position, developing a peculiar strategy. According to the circumstances, the King would sometimes benefit one, and sometimes others, interested in profiting from both military supports, because the Crown did not have a permanent army. The problem had aroused from mid-13th on, when reconquest had reached an end. Somehow, the King and the friars seemed to have disruptive military behaviours. The reconquest war was of course just one kind of war. And so, from the end of the reconquest on, the war keeps on as a core question to the Crown, and the friars would be involved in some military campaigns against Christian kingdoms (namely in Castile), and against Muslims (namely around the strait of Gibraltar). Although the main cases are already known, the documental sources have plenty of information crucial for a systematic approach regarding the practice of the war by the Military Orders in late medieval times.