Introduction

Among medieval history scholars, knights and chivalry represents the enduring focal point in numerous studies of medieval conflict. Perhaps this testifies to the prevailing interest in the perception and promotion of ideas of war rather than war and military organization itself. In this respect, there is a rift between medieval historians and military historians. For long, the latter group have pointed to the decreasing military importance of the nobility during the later Middle Ages, and to the increased importance of other social groups who organized militias that quantitatively often dominated the battlefields1. The emerge of militia organizations is connected to the gradually growing size of armies, paralleled with the continuous economic and organizational inability of medieval states to manage standing armies. Militia organizations was a strategy of outsourcing that paralleled noble cavalry service in exchange for tax exemption.

Many medieval European polities were characterized by an internal struggle between rulers and the aristocracy. Therefore, rulers sought military power bases outside the feudal structure, which partly explains the increasing importance of mercenaries during the late middle ages (KIERNAN, 1957). In this perspective, however, domestic non-noble militia organizations under royal command should have had a similar effect. With militia organizations, rulers could sometimes exercise power more independently in relation to the nobility. From this perspective, the development of medieval militias under royal command looks like an early step towards the centralization of royal power, or, at least, it favored the path into a growing bureaucratization of war performed by royal authorities.

Several scholars have also conceptualized the military developments during the later middle ages as an ‘infantry revolution’, where the military importance of the common foot soldiers markedly increased to the detriment of the heavy cavalry2. In terms of weapons’ technology impact, the longbow and the pike have received much attention as instruments of change on the battlefield. With some notable exceptions, the crossbow has seldom been ascribed a corresponding importance. Hardy McNeill characterizes the crossbow as «a great equalizer in the field», which very effectively increased the importance of infantry while the significance of feudal cavalry correspondingly crumbled3. Due to the technical improvements, by 1400, the crossbow had developed its full potential and become the most important military projectile weapon in Europe (McNEILL, 1984, p. 80; ALM, 1947, p. 130; EKDAHL, 1998; ALM & BRUHN HOFFMEYER 1956, p. 238). It is probably wrong, however, to attribute this to a purely technologic change. It was rather due to the fact that crossbow was powerful, fairly cheap to manufacture and easy to use. When manufacture increased and its tactical implementation changed, so did warfare (McNEILL, 1984, p. 67-70).

These late medieval military developments have frequently been studied in Western Europe, whereas similar developments in other parts of Europe have received less attention. The purpose of this paper is to widen the geographic scope with a comparative study of the infantry organization in late medieval Sweden and Portugal. These two realms seem to conform to the general pattern, where the crossbow played a prominent part in warfare throughout the later middle ages.

Why compare such unrelated societies as Portugal and Sweden? Both realms were part of the same Latin Christian transnational community, but they were geographically separated and located on each side of medieval Europe. With some degree of certainty, we may assume that very little direct cultural transfer affected military organization in each realm, which thus developed along independent lines. Those influences, however, could come from central Europe and this paper is a good test tube to understand how war technology evolution has spread in two medieval European peripheries. Methodologically, thus, we have two somewhat ‘unpolluted’ samples to compare. This makes them well suited for a comparison on military developments, in terms of both army organization and the diffusion and application of weapons’ technology. Furthermore, a comparative study between two European peripheries also provides the field of medieval military history with a broader scope for future comparative studies, necessary to understand better the quite diverse organization of armies in medieval Europe.

On the outset, there are some obvious differences as well as apparent similarities between the two units of comparison, which needs to be specified. In terms of chronology, an asymmetry is built into the chosen comparison. The Portuguese crossbow militia can be traced back to the end of the thirteenth century, whereas its Swedish equivalent cannot really be studied in the extant sources until mid-fifteenth century. In this study, we accept this fact as a methodologically transparent discrepancy variable.

Both realms were somewhat geographically peripheral, neither densely populated nor especially economically developed. In terms of social structures, Portugal was more urbanized than Sweden, and demographically Portugal (around 1 500 000 inhabitants) was about twice as big as Sweden (MARQUES, 1987, p. 16; FORSSELL, 1872-1883). Both realms had a peninsular geographic position. Portugal was situated on the Atlantic rim in-between Spanish and Muslim powers, while Sweden was positioned at the inland Baltic Sea and cornered by several types of rival polities. Even though neither realm initially played a major political role, Portugal with its close connections with south European Kingdoms and its alliance with England, arguably played a greater international role during the Middle Ages than Sweden.

In 1249, Portugal extended its territory with the conquest of the Algarve. From this time onwards, royal power grew progressively and the Portuguese Crown increasingly competed with the neighboring kingdom of Castile. In 1415, Portugal also started an early colonial expansion with the conquest of Ceuta. In the thirteenth and early fourteenth century, Sweden saw a promising growth of royal power, with intermarriages with German and Flemish houses. The fifteenth century, however, was characterized by recurrent political crises and a discontinued royal power. It was not until the 1520-s that a stable political rule was established, but from that point onward within a few decades Sweden gradually developed into one of the first European fiscal-military states, and during the seventeenth century, it temporarily dominated the whole Baltic Sea region.

In both Portugal and Sweden, we find militias armed with crossbows, which played a prominent military role in each realm. These militia organizations do share some common features which makes them suitable for comparison. In both cases, the militia functioned as one of several components within a heterogeneous army structure, were they represented the most important non-noble military units. They both had a similar kind of tactical function within the larger military organization. They also had similar arms and equipment and they both played a decisive role in warfare. Finally, both organizations had a long-term organizational impact, and represented models for subsequent military organization and recruitment systems.

The two cases will be compared in terms of origins, organization, leadership, relation to state or royal power, forms of service reimbursement, strategies of recruitment and training, campaign performance, estimated professionalism and impact on martial society. The aim is further to assess on what points we find similar developments, but also how they differ and the possible reasons for it.

The militia in later medieval Portugal (1299-1498)

The Portuguese Medieval armies were not formed by permanent or professional contingents, they did not have strict units or commands and neither did its men live in barracks or quarters. Such developments only slowly and gradually began to appear in the European West, in the second half of the fifteenth century. Until that time, the Portuguese royal military host was formed by an assembly of several political fractions which were invested with different degrees of autonomy. The army recruited by the Portuguese Crown, at the end of the middle ages, was profoundly heterogeneous, recruited within an ad hoc system, and destined to meet the specific needs of a campaign or for the defence of a city or territory (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 27). Regarding army numbers, João Gouveia Monteiro, estimates that the Crown could field a host of around 3200 mounted men-at-arms. The medium estimate of two crossbowmen or men from the peonage for each knight, gives a total of around 10 000-12 000 combatants in the Portuguese royal host (MONTEIRO, 2003, p. 204-207).

The composition of the Portuguese medieval military forces, can be divided into four distinct types: the knights of the secular aristocracy; the militias recruited within the cities; the warriors of the Military Orders; and, finally, the «homiziados» - convicted criminals who did military service as a penance (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 31). However, as Monteiro emphasizes, this division is rather a methodological conceptualization than a clear-cut reflection of the more complex real organization. This artificially geometric model however allows us to ‘slice up’ and simplify the military organization in order to study some of the separate corps of which the Portuguese royal host was composed in the late Middle Ages (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 27).

Among the different corps, there were three different kinds of crossbow militias. Of these, the «besteiros do conto», created in 1299, formed the perhaps most important component in the Portuguese armies. Because of this - and due to the fact, that, to date, it has been more thoroughly studied than the others have - it is the most suitable Portuguese militia type for this comparison.4 The creation of this military force by the Portuguese Crown was an official recognition of the importance both of the crossbow and of urban forces in the warfare on the Iberian Peninsula, where pitched battles were rare and the commanders often preferred assaults or sieges.

In Portugal, the written sources indicate that a crossbow corps was established within the municipal forces, before the royal creation of the «besteiros do conto» (crossbowmen). Since the twelfth century, the municipal authorities recognized the military effectiveness of the crossbowmen. They encouraged urban centres to designate men apt in handling the crossbow by giving them attractive privileges (BARROCA, 2003, p. 140).

Due to the military importance of these soldiers, they increasingly became more autonomous in comparison with other types of infantry. They had an autonomous command structure, headed by the «anadéis» - the officials responsible for the recruitment and command of these corps. In the mid-thirteenth century, these officers were appointed by the municipal authorities to control the voluntary enlistment of men to this socio-military group. However, due to a logic of military planning, and because the municipal authorities wanted to control the number of individuals who could benefit from important fiscal and legal privileges, the selection was restricted and limited to a predetermined number of men (MARTINS, 2008, p. 378).

In contrast to the Swedish case discussed below, the original establishment of the Portuguese crossbowmen militia is documented in the extant source material. King Dinis of Portugal (1279-1325) realized that these shooters could provide a more efficient military service if they had their own legal structure and if their effectives were predetermined by the Crown. To achieve these objectives, King Dinis established a «conto» (MARTINS, 2008, p. 379), where a certain number of crossbowmen were assigned to each recruitment unit, coinciding generally with a city or a village (MONTEIRO, 2003, p. 197). The «besteiros do conto» militia was created and transformed into a stable military force, regularly trained and capable of quickly mobilizing whenever the Crown called for it to serve.

The first references to the «besteiros do conto» are found at the end of the siege of the Portuguese city of Portalegre, during the conflict between King Dinis and his bastard son, Afonso Sanches. In the aftermath of this operation, the Portuguese King rewarded the «besteiros do conto» of Serpa with some privileges as a gratification for their role in the battle. However, these privileges were not consigned in a single manuscript, but divided into three documents dated from 24 October 1299. To them were added others from 1304, 1309, 1319 and an undated document attributed to King Dinis reign. This dispersal into several manuscripts is quite revealing, both of the incipient way in which the privileges were granted and of the lack of any pre-existing model at the time that could have served as basis for the granting of such privilege letters. We can however ascertain that those 1299 manuscripts were the first royal privileges granted to the «besteiros do conto» (MARTINS, 2008, p. 379-380). Furthermore, in the initial phase of this military force expansion, most of the royal privileges letters given to the new militia contingents were based on those granted to the «besteiros do conto» of Serpa. It indicates that this town was the first to benefit from privilege letters for their «besteiros do conto», serving as a model for the creation of subsequent units (known as «anadelarias») in the following years (MARTINS, 1997, p. 95-96).

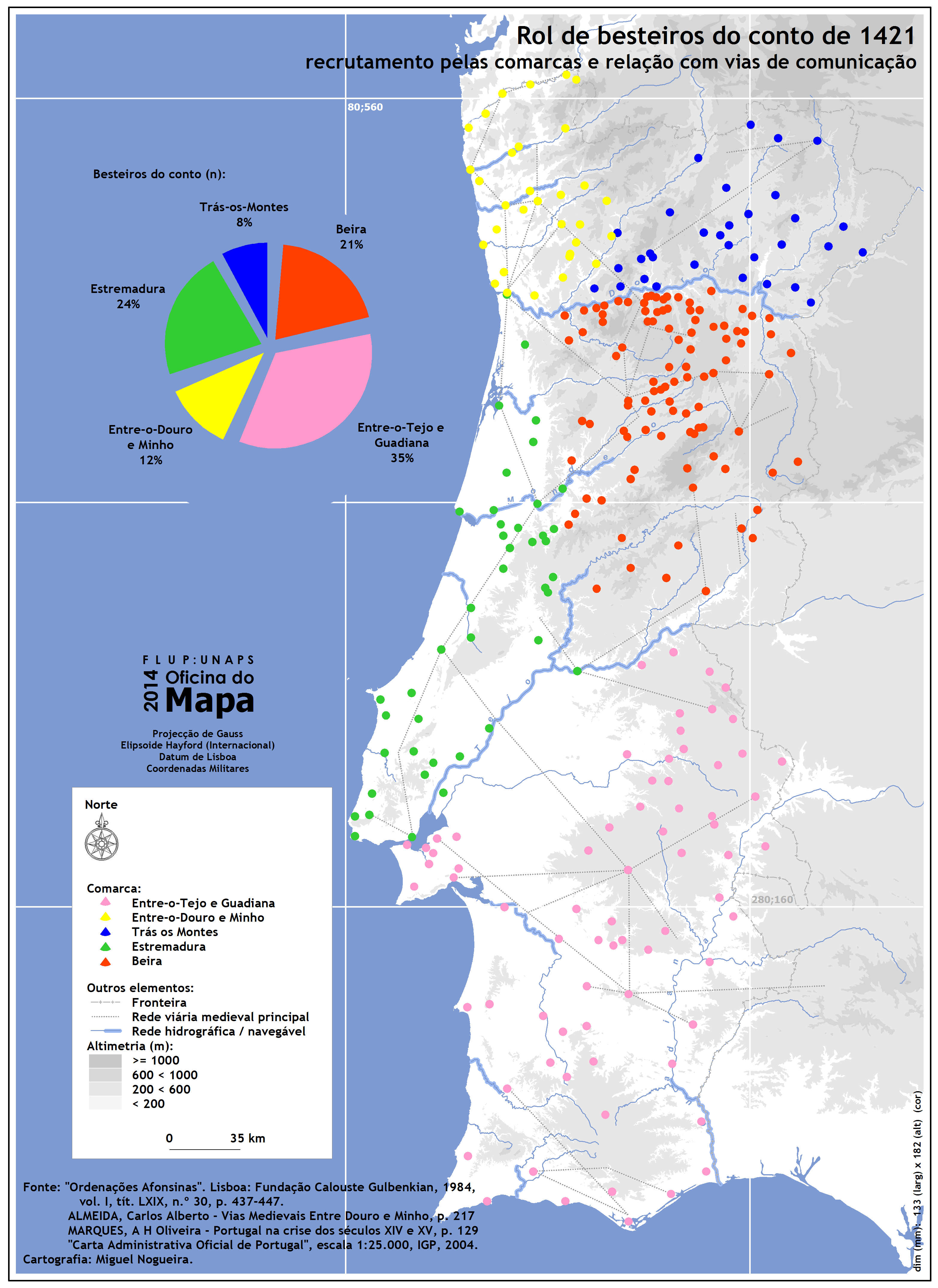

In contrast to Sweden, described below, there seems to be a difference in the distribution of recruitment between Portuguese geographic areas, at least during the first years of the militia. In a first phase (1299-1322), the militia organization only expanded geographically in the Southern region of the Tagus river. The reasons for this are unclear, but it may have been related to a conscious defensive strategy. The «besteiros do conto» were established in regions located near one of the most important penetration axes into Portuguese territory: the geographic triangle formed by the Portalegre, Elvas and Évora cities, as well as the left side of the Guadiana River. This area also served as an important basis for offensive military operations against the Castilian Estremadura. In addition, many of these recruitment units were under the jurisdiction of the Military Orders of Santiago, Avis and Temple. This fact demonstrates an aggregation of interests between these institutions and the Portuguese Crown, with the aim of improving the quality of the military contingents established in their territories. Finally, the secular aristocracy was less represented in the South of Portugal, compared to the North. The royal establishment of the «besteiros do conto» in Southern Portugal consequently met with less political resistance (MARTINS, 2008, p. 381). In contrast to the nobility-dominated North, in the South the organization of urban centers proved most permeable to develop military organization and thus ideal for the recruitment of «besteiros do conto» (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 115).

The successors of King Dinis - the Kings Afonso IV (1325-1357), Pedro I (1357-1367) and Fernando I (1367-1383) - continued the organization of the «besteiros do conto». During their reigns, the militia expanded practically throughout the Portuguese territory, which resulted in a subsequent increase in the number of combatants enrolled in this military force (MARTINS, 2003, p. 1203). From the reign of King Dinis to that of King Afonso IV, the militia units in the kingdom increased from 17 to 29. At the end of King Dinis reign, the whole militia organization had hardly exceeded 450 men. During King Alfonso’s reign, the expansion, especially with the establishment of the «besteiros do conto» in large cities, such as Lisbon, allowed for the theoretical mobilization of around 1300 crossbowmen.

King Pedro I’s contribution to the enlarged ranks of «besteiros do conto» with 14 new recruitment units, represented an increase of around 300-400 crossbowmen. On the other hand, King Fernando probably created twelve new «anadelarias», to which we can add another nine, whose oldest documents are not dated, but points to his reign. Together, all these new «conto» were responsible for recruiting around 459-481 crossbowmen. To sum, at the end of King Fernando’s reign, the crown commanded 2015-2215 «besteiros do conto» (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 65).

The only list of «besteiros do conto» which details the number of combatants recruited throughout the whole kingdom dates to 1421, during the reign of King João I (1385-1433). This document includes 4887 crossbowmen, divided among 300 recruitment units. Compared to the Portuguese population of around 1 500 000 people and to the volume of the Portuguese Medieval armies at the time, the crossbowmen militia represented an impressive number of combatants (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 61). During two centuries, the «besteiros do conto» successfully served the Portuguese kings on their military campaigns. The end of the militia came in 1498, where King Manuel I (1495-1521) decided for the termination of this organization. However, its legacy did not end at that time. The organization model of the militia served as a basis to the creation of the «espingardeiros do conto» (harquebusiers), after the introduction and propagation of the firearms in the early sixteenth century (MARTINS, 2008, p. 395). Finally, the predetermined number of combatants is also a marked distinction in comparison with the Swedish model.

Regarding the recruitment of «besteiros do conto», the municipal authorities (judges and councillors) had an obligation to inform the local «anadel» about the men who were eligible for military service (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 63). The selection process and subsequent recruitment are illustrated by the instructions sent by King João I, in 1421, to the «anadel-mor» (commander-in-chief) of the Kingdom. The King ordered that if the numbers of recruited soldiers in each unit were insufficient, the local «anadéis» (or, if present, the «anadel-mor») should require the judges, councillors and other city officers to present a written list of the most suitable men to recruit for the militia5. The municipal authorities must respond within three days6, and the names presented in the list should satisfy some requirements: the men had to be wealthy enough to buy and maintain a good crossbow; they had to be young, married and they had to own a house. These norms probably represented a form of guarantee that the recruited men lived continuously in each recruitment unit (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 144). However, in contrast to a wider recruitment policy in Sweden, one of the main concerns of the Portuguese Kings was the need to recruit soldiers from the group of craftsmen, having preference for those who showed crossbow shooting skills. Within this group, priority was given to the men skilled in crafts, which required a certain manual dexterity, such as cobblers, tailors, carpenters, masons, blacksmiths, muleteers or coopers. In order not to affect the supply of food, however, the Crown dictated that militiamen must not be recruited among farmers.7 The preference for craftsmen is demonstrated in list from 1348 of «besteiros do conto» from the village of Guimarães, whose «conto» of 20 crossbowmen was composed of nine tailors, six cobblers, three shearers, a blacksmith and a goldsmith - all of them were craftsmen.8

However, if the municipal authorities could not find enough suitable artisans for each unit, they were allowed to recruit outside this group on condition that the recruits were young, proprietors of a house and knew how to shoot a crossbow9. Furthermore, it was forbidden to enlist men from other municipal militias10. The selection could also be completed by volunteers who, ‘by their own desires’, wanted to enlist as «besteiros do conto» (essentially, because they wanted to enjoy the privileges reserved for this militia). In these cases, the «anadéis» should mention in their registration books that these crossbowmen were enlisted by their own will11.

Based on the list of the qualified individuals, the «anadel» or the «anadel-mor» should summon and muster the men, to assess their physical condition and their skill with the crossbow. After being enlisted, the new militiamen should receive an official letter to confirm their new status of «besteiro do conto», which contained a set of privileges and duties. The militiamen had a special payment system, which initially consisted on a stipendiary payment after six weeks of compulsory military service. In 1400, however, King João I (1385-1433) imposed that the payment should be done immediately after the military campaign (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 78). The «besteiros do conto» enjoyed several legal rights like those of non-noble knights. They were exempt from several municipal taxes, which can be seen as a similar privilege in comparison with the Swedish case; they enjoyed the direct protection of the King and they had the right of civil trial by their «anadel»; they had the right to own and carry weapons throughout the territory, «on condition that they did not cause damage with these weapons or wander around outside late at night» (FERREIRA, 2014, p. 69). Finally, they received retirement benefits once they reached the age of 70 years, without losing any of the privileges that they have enjoyed before (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 65-68).

Regarding duties, the «besteiros do conto», had to perform weekly training exercises on Sundays; they had to own and maintain their armament in good conditions, to have a specified amount of ammunition and to keep a high degree of readiness. These criteria testify to the authentic elite force characteristics of these soldiers (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 199-200). Besides that, they also had the obligation to transport prisoners and money between Portuguese cities and they should serve during six weeks in military campaigns without receiving wages12. Finally, within the recruitment units they were also responsible for minor police tasks (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 68).

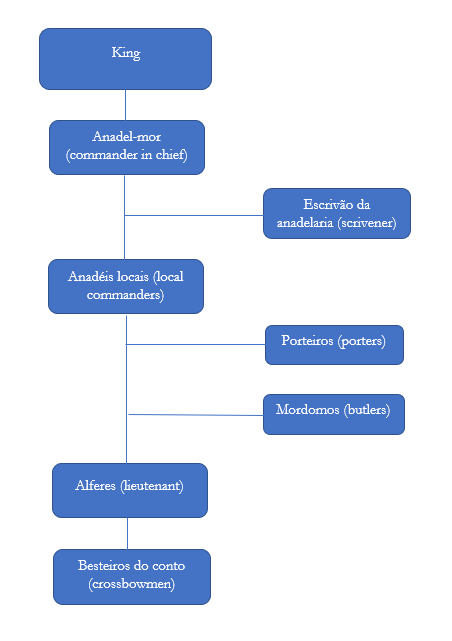

In first place, the militia heeded to the King and to the Princes. The exponential growth in the number of «besteiros do conto» as well as recruitment units led to the creation of a superior autonomous command structure during the reign of King Pedro I, represented by the «anadel-mor» (commander-in-chief). He was an official responsible for the coordination of all the «besteiros do conto», but also for supervising the functions of their local commanders («anadéis») (MARTINS, 2007, p. 175). Because of the royal nomination, almost invariably, noblemen were appointed to the office of commander-in-chief (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 25-130). They were responsible for the supervision of the local «anadéis», especially concerning the process of recruitment. If necessary, they were required to be present to decide if the men chosen fulfilled the necessary requirements for militia service - to ascertain that they were in good physical condition and sufficiently skilled with the crossbow. This autonomous structure of command stands in significant contrast to that of the Swedish militia, discussed below, which neither had special military appointments, nor a continuous and permanent leadership.

At the end of the fourteenth century, sources refer to a scribe who was responsible for accompanying the «anadel-mor» at the muster of the «besteiros do conto». This fact demonstrates the complexity of the missions assigned to these officers, which was mainly due to the administration of the great number of combatants (MARTINS, 2008, p. 390).

Located lower down in the hierarchy of the militia’s organization structure, we find the «anadéis», officers who were responsible for the local contingents of crossbowmen. Initially, they were elected among the members of the militia (FERREIRA, 1988, p. 188). The «anadel» performed his function for one year, and then he returned to his previous status of «besteiro do conto» (MARTINS, 2014, p. 157). Since the end of the fourteenth century (probably around 1392), this form of election was gradually abandoned and transformed into a nomination process performed by the higher authorities within the military hierarchy: the Portuguese King and the «anadel-mor» (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 133). Towards the end of the fourteenth century, this process seems to have been a ‘tug-of-war’ between the customs of the cities’ organization and the ambitions of the Crown (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 71). Probably neither faction truly won this struggle. Therefore, the solutions found «would have been subject to the geography of regional (economic and political) powers, which profoundly and indelibly marked the different situations of the various ‘anadelarias’ throughout the kingdom» (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 71).

Therefore, as soon as the local «anadéis» were elected by the militiamen - or nominated either by the King or the «anadel-mor» - they were endowed with several powers. The officials played the role of military commanders in case of a mobilization and since they should judge minor legal disputes regarding the civil rights of the crossbowmen, they also had a degree of jurisdictional power. The «anadéis» also performed inspections of the condition of the armaments of the individual militiamen. In addition, these officials also benefited from better monetary prerogatives, since they received higher campaign payments compared to their subordinates. The «anadéis» had the responsibility to summon, coordinate and supervise the militiamen in weekly training exercises. Finally, the «anadél» should replace the missing crossbowmen in each recruitment unit (by death or retirement) with other suitable men. For this purpose, they should write the names of the new soldiers in a register, which should contain their professional occupation, as well as other personal information, to better organize the militiamen under their supervision. Unfortunately, these registers have not been preserved (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 136-137).

Further down in the chain of command, the sources also indicate the existence of lesser officers, at least within the more numerous contingents. Such an example was the «alferes» (corresponding to a lieutenant), which indicates that the «besteiros do conto» could present themselves at the military campaigns with their own urban centre flag (MARTINS, 2007, p. 176). This is supported by a donation of 1385, in which King João I indicated that, even though the village of Torres Vedras have been donated to the city of Lisbon, the «besteiros do conto» of Torres Vedras should continue to fight with the flag of their village and set up the military camp next to it13. Finally, the sources also reveal the existence of a «mordomo» (butler) and a «porteiro» (porter) in each recruitment unit. These men performed administrative tasks and were were probably elected in the same way as the local «anadel» (MARTINS, 2014, p. 157-158).

Because of the character of the preserved source material, it is difficult to study the performance of the «besteiros do conto» in the medieval military campaigns, in any degree of detail. The Portuguese narrative sources, such as Chronicles, often laconically only refers to the term «besteiro» (crossbowmen), which does not refer specifically to «besteiros do conto». Because of their military effectiveness and their capacity to mobilize quickly, with a predetermined number of combatants whenever the Crown demanded, we may assume, however, that they held a prominent position within the royal military organization.

The medieval Castilian chronicler, Pero López Ayala, ascertain their importance in his comments on the decisions of 1390’s Guadalajara Courts, where he regretted that no substantial numbers of crossbowmen had ever been organized in his own kingdom, and «the infantry cannot perform effectively in war without the crossbowmen».14 This is also reflected in the performance of the Portuguese «besteiros do conto», which part-took as a versatile force in naval as well as land warfare, in pitched battles and sieges of castles and fortified towns, in regional operations and even in the African campaigns.

According to Miguel Gomes Martins, the «besteiros do conto» used crossbows with hook and stirrup, and these weapons were described as «crossbows cocked with the use of the belt» (MARTINS, 2007, p. 261). The crossbowmen wore a hook dangling from their belts which they used to cock the bowstring in the nut (MARTINS, 1997, p. 110). The combined use of the hook and stirrup facilitated the process of cocking the crossbow, since the shooter no longer needed to manually pull the bowstring (MONTEIRO, 1998, p. 534). This kind of crossbows were common among the «besteiros do conto» until the beginning of the fifteenth century, when the new lathe spanning mechanism was introduced (MARTINS, 2007, p. 261). A Royal law from 1417 imposed that the «besteiros do conto» should start to use these new spanning mechanisms15. The lathe mechanism enabled the use of stronger bows and strings, which made the weapons much more powerful. However, a Royal instruction from 1421 indicates that the militia had not yet completely abandoned the use of hook and stirrup. The king instructed the «anadel-mor» to make sure that the «besteiros do conto» kept their crossbows in good conditions, but also the belts as well as the lathe systems16. In conclusion, sources indicate that the hook and stirrup prevailed for long in the armament of the «besteiros do conto», and was only gradually replaced by more advanced crossbow mechanisms during the fifteenth century (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 156).

Apart from the crossbow, the «besteiros do conto» should also be armed with two darts -short and thin throwing-spears, suitable to throw at short distances17. This complementary armament was probably due to the need for defence in short range combat situations and because of the time consuming process of reloading the crossbow (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 162-163).

The «besteiros do conto» were also expected to carry some sort of protective armour However, the sources gives us few details of the nature of it. According to the fore mentioned list of «besteiros do conto» of 1384-1388, the militiamen should have a bascinet with a visor18. Even though, little is known about other types of armour, we may assume the use of some protective armament in addition to the bascinet. It must also largely have depended on the wealth of each militiaman. The regular military inspections had a very important function in verifying the good state of offensive as well as defensive armaments of the «besteiros do conto». In addition, the mandatory weekly training exercises likewise both required and impelled the preservation of their armament in good conservation (FERREIRA, 2015, p. 163-164).

In Portugal, as stated above, the «besteiros do conto» should perform weekly military trainings on Sundays (not to interfere with their professional activities), in a large public space located in each recruitment area. Led by their «anadel», the militiamen performed crossbow shooting on a static target, referred to in the sources as a «tiro à barreira» (barrier shooting) (MONTEIRO, 1998, pp. 439). There, they perfected their aim and the technique to rapidly substitute the crossbow strings (FERREIRA, 1988, p. 206). They should also learn how to prepare the tips of the arrows («virotões») with a poison deriving from several different plants19.

In addition to the barrier-shooting exercises, game hunting certainly also prepared the crossbowmen for war, which activity was encouraged by the Crown through the granting of privileges regarding fiscal exemptions whenever the militiamen sold the felled game at the marketplace (MARTINS, 2014, p. 308). While hunting often offered moving targets similar to those of military situations, some crossbowmen possibly also practiced joint shooting coordination during hunts. The importance of paramilitary training exercises is highlighted by documents from the reign of King Pedro I (1357-1367), where «besteiros do conto» were obliged to annually hunt a stipulated number of eagles in order to maintain their privileges20.

The Militia in late medieval Sweden (1450-1540)

In Sweden, the late medieval period was characterized by a complex political situation. The somewhat strong royal power of the early fourteenth century was discontinued and in 1397, Sweden entered the Kalmar union with Denmark and Norway. This new polity was largely run from Copenhagen, and the centralized Danish rule gradually caused discontent among the Swedish nobles. In the furious Engelbrekt uprising of 1434, the union king Eric of Pomerania was ousted, and a sequence of native kings or Governors of the realm (Riksföreståndare), and subsequent union kings followed during decades of war and civil turmoil. A somewhat steadier rule was established during the period 1470-1520, when Sweden was mostly ruled by native governors of the realm. They waged a number of defensive wars against the Danish Oldenburg kings, who maintained their claims to the vacant Swedish throne.

Up until this point, the Swedish state was weak. In order to organize military matters the rulers had to negotiate with and to coordinate forces from all strata of society. This was a martially seasoned society, but it was decentralized and difficult to organize into proper army units. There was no permanent army establishment and any army had to be raised anew. In 1521, the Swedish nobleman Gustav Vasa eventually managed to claim the throne. He reorganized the realm into an early modern centralized state and gradually also created a standing army (GLETE 2006, pp. 174-212).

The Swedish realm (including Finland) comprised of a vast territory, which was heavily forested and sparsely populated. The nobility comprised of around 500 men, capable of fielding around 2000 men in total, of which almost half were troops in the service of the seven bishops, who acted as prominent military leaders and often opposed the temporal rulers (NEUDING SKOOG, 2018b). The few and small Swedish towns organized high quality expeditionary forces which perhaps amounted to 500 men (NEUDING SKOOG 2018a, p. 310-314, 534-535). The military trump card of the Swedish realm, however, was its peasant militia. When politically motivated to mobilize, rural society was able to field thousands of crossbow men. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, every Swedish army was mainly composed of this militia of crossbowmen.

In contrast to Portugal, where sources allow for a closer study of the militia, the origins of the Swedish peasant militia remain obscure. The handful of preserved district laws of the early fourteenth century testify to regulations of the military duties of all able men, where the prescribed armament is quite detailed (but did not yet include crossbows). These regulations stemmed from the gradually obsolete Viking age naval recruitment system (Ledung) which nominally still prevailed. Local society was still obliged to put ships to the king’s disposal for the defence of the realm. However, the scarce source material tells us virtually nothing about operations during the fourteenth century and by 1400, it was disbanded altogether.

King Magnus Eriksson’s (1319-1364) law of the realm, ratified in 1351, contained formalised rights and duties for all subjects of the realm. Interestingly, this law is quite vague on the military organization and only emphasizes the general obligation for every able-bodied man to aid the king in the defence of the realm. In face of war, the law prescribed negotiations between the bishop, the chief district judge as well as six peasant and six noble representatives of local society which must precede mobilization, to determine what aid a district ‘shall or should’ give the king21. Consequently, political negotiations were a central element in this system. In contrast to Portugal, there seems to be no clear difference between geographic areas.

The first clear evidence of strong peasant militia units taking part in warfare emerge from the Engelbrekt uprising of 1434, where the chronicles speak of numerous units storming and burning several castles throughout the realm (JANSSON, 1994; GEJROT 1996, p. 206-213; KLEMMING 1866, p. 28-90). However, the militia cannot be examined in closer detail until the later fifteenth century. From this point onward, rulers regularly used it for defence against invading armies as well as in local feuds and in offensive warfare. For instance, during King Karl Knutsson’s invasion of Danish Scania in 1452, a large host of well-armed militia joined, which points to a well-established system already in existence at this time.

Sweden was a distinctively rural realm with few towns and a small noble class. The vast social majority were common peasants of three categories: tenants of the nobility, crown tenants and freeholder peasants, of which none was serfs but only the last category were landowners in their own right. The tenants of the nobility were supposed to enjoy a light burden of military drafts, but towards the end of the Middle Ages the crown’s increasing military demands taxed them for manpower as heavy as other peasants.

For the purpose of taxation as well as military recruitment, the representatives of the crown determined the number of able men (Mantal) above 15 years of age in each sub-judicial district (Härad) (NEUDING SKOOG 2018a, p. 385f). For the mobilization of the militia, the crown representatives then demanded a certain quota of the available number of men, ranging from every second, to every eighth man, while every third or fourth man was the most frequent quota (NEUDING SKOOG 2018a, p. 391f, 647f). A local or regional peasant judicial assembly was summoned to grant the crown’s demands, which made the militia system a distinctively collective enterprise (NEUDING SKOOG 2018a, p. 401-405). This is a marked difference in relation to the individual contract character of the Portuguese militia.

Apart from the fact that the militiamen were recruited from the rural common estate, little is known of their social origins. Many were supposedly of very humble origins, but to judge from several letters from this period, some also wore plate armour (Harnisk), which testifies to the decent economic standing for at least a part of the militia (HADORPH, 1676, p. 252-253; BSH 5, p. 470) (HADORPH, 1676, p. 252-253; BSH 5, p. 470). As the contemporary fifteenth century chronicle Karlskrönikan narrates Karl Knutsson’s campaign to Scania in 1452, it describes mounted militiamen in plate armour, «equipped like men-at-arms» and skilled to cock and shoot their crossbows from horseback (KLEMMING 1866, p. 295).

As several scholars points out in sixteenth century England, Germany and Livonia, it was often the reasonably affluent members of local society who possessed sufficient quantities of armour, but it was the poorer echelons of the community who were nominated to wear the harness to war (RAYMOND, 2007, p. 128; BAUMANN, 1994, p. 64; KREEM, 2001, p. 40-41). This might have been the case also in Sweden, but the apparent skill and wealth of the mounted soldiers in the militia clearly suggest that at least part of it was composed of men from the middling peasant elite. Additionally, a statute from 1437 which prohibited the carrying of crossbows, mail shirts and other martial equipment at social gatherings also addressed the day-labourer category (Hjon) of local society, implying that even they might own weapons and armour (HADORPH 1687, p. 45). Still, it was likely a collective concern in local society to fit out the militiamen, where weapons and armour were pooled together by a number of peasants. This practise differs from the Portuguese case, where every militiaman was supposed to be wealthy enough to own his own equipment.

When King Gustav Vasa gradually introduced an enlistment policy in Sweden during the sixteenth century - which transformed the militia into a standing army-, the landless and poorer categories of rural society were especially sought after as potential soldiers. Those who neither owned land nor paid full tax - such as rural craftsmen, skinners, tailors, farmhands and unmarried men - were considered particularly suited to serve in the army. In contrast to peasant husbands, the conscription of these men did not directly upset the agricultural production cycle in local society, which was beneficial for the crown as well as for the peasants (NEUDING SKOOG, 2018a, p. 88-89; HALLENBERG & HOLM, 2016, p. 98-102; LINDBERG, 1964, p. 28).

The early fourteenth century district laws considered every man above 18 or 20 years of age eligible for service, while the common practice from the fifteenth century onward was to count every man above 15 as able to serve (YRWING, 1965, p. 303; HOLMBÄCK & WESSÉN, 1979, p. 47; NEUDING SKOOG, 2018a, p. 398-399). In the early sixteenth century militia as well as in the later army of Gustav Vasa, it was frequently stated that the men should be young, alert, agile and unmarried (BSH 5:50; GIR 1532-1533, p. 46, 97; GIR 1534, p. 148-149; GIR 1542, p. 88f, 95, 124, 152; GIR 1543, p. 18, 41; KLEMMING, 1870, p. 56). The purpose of this policy undoubtedly was to preserve the landowning taxpayers and to make good use of the social surplus of local society.

The practise of picking out the young and unmarried men differs sharply from the Portuguese militia organization, where the soldiers were supposed to be married as a requisite for service. In Portugal, the militia should not be recruited from among the farmers themselves, but from other social categories such as craftsmen. In Sweden, lack of social stratification meant that a heterogeneous social mix of men served in the militia. Due to the collective tax reductions in exchange for service, the service in the militia also seem to have carried political weight and advantages. Consequently, it also attracted prominent members of local peasant society (NEUDING SKOOG, 2020 [Forthcoming]). Nevertheless, the crown did not regulate the social composition of the militia and was satisfied if local society fielded the desired number of men.

Local or regional peasant judicial assembly was summoned to grant the crown’s demands, often requesting the ruler to lower the annual district taxes to compensate for the military costs. The service of the individual militia man (Utgärdskarl) was never reimbursed in ready money, but through the tax exemptions received by the district as a whole, which made the militia system a distinctively collective enterprise (NEUDING SKOOG, 2018a, p. 401-405). The only apparent duties for the militiamen was to obey their commanders on campaign and to continue to serve for as long as he provided them with provisions. Both the collective reimbursements and the lack of formalised duties represents a marked difference in relation to the Portuguese militia, whose soldiers received individual payment or privileges for their service.

During the Danish occupation of Sweden in 1520, the captain Sören Norrby wrote anxiously to his King Christian II. He had been instructed to pacify the population and consolidate the king’s position in the district of Kalmar. However, the royal demands for the peasantry to turn in their crossbows for destruction (on the penalty of death), met with fierce resistance. According to Norrby, for the last decade the peasantry had a standing agreement with the Swedish crown, to keep 1 000 fully equipped crossbowmen at the ready, in exchange for full tax exemption for the whole district («Smålandslif», 1900, p. 302). Of course, this advantageous economic position would be lost if they agreed to hand in their crossbows. The large-scale Swedish uprising in 1521, successfully completed by Gustav Vasa, was partly a consequence of this policy to disarm the peasantry. It is unclear however, whether the privileges enjoyed by the Kalmar peasants applied also to other districts. This agreement, nevertheless, sheds light both on how heavily the Swedish rulers depended militarily on the peasant militia crossbowmen, and on the prospects of collective economic benefits inherent in the bargaining process of military service.

In Sweden, there is hardly any mentions of commanders recruited from amongst the peasantry and no higher capacity to lead among the peasantry itself. Instead, it was the crowns’ local representatives, such as bailiffs, chief district judges, fief holders, or men from the feudal social organization, such as local knights or lesser noblemen, who acted as captains over the militias. Consequently, the military hierarchy corresponded to the social hierarchy (NEUDING SKOOG 2018a, pp. 368-376). On the local and regional level, political power was largely delegated to the aristocracy, which consequently also had a great local military influence.

In contrast to the Portuguese militia, in Sweden there were no special military appointments over the militia units, little permanent leadership and no autonomous structure of command. The bishops, the chief district judges, fief holders and castellans often automatically functioned as captains over any militia units mobilized in their own district. As is also evident from Portuguese examples22, the Swedish peasantry sometimes petitioned the crown if they considered their district judge an inadequate military leader. In 1511, the peasantry in Kåkind complained that their district judge Johan Månsson did not want to risk his life for them. In his place they suggested another man of the Gentry, Lindorm Brunsson, as a more suitable and daring captain23. The appointments of district judges was a serious matter for the peasantry because it also determined the competence of the military leadership who would march them to war.

In Sweden, the crossbow was introduced quite late. It is first mentioned in 1286, in the last will of the knight Karl Estridsson, in which he gave two crossbows to the king (SDHK, 1336). Such a gift would hardly be considered suitable unless it was a rare technical commodity at the time. Until the fourteenth century, this weapon is mostly found in an aristocratic milieu, and was gradually spread to other social groups with the influx of Germans in the towns of the Swedish realm (ALM, 1947, p. 130, 141-142; ALM, 1945, p. 198). In the early fourteenth century district laws, the common bow was still the prescribed projectile weapon. For instance, the law of Södermanland prescribed a helmet, mail shirt or plate armour, sword, shield, spear and a bow with three dozen arrows (YRWING, 1965, p. 303; SCHLYTER, 1838, p. 190; HOLMBÄCK & WESSÉN, 1979, p. 108, 76, 208; LJUNGQVIST, 2014, p. 208). However, during the fifteenth century the bow virtually disappeared as a military weapon. Instead, the crossbow quickly became very popular among all social groups in Sweden, and sources abundantly refer to it as dominating military weapon (NEUDING SKOOG 2018, p. 119, 334, 337, 411). The sixteenth century author Olaus Magnus also stated that there was hardly any man in Sweden that did not own a crossbow (OLAUS MAGNUS, 2001, p. 294).

The increased emphasis on the crossbow is also evident from a militia muster in the district of Värend in August 1505. The nobleman Erik Trolle reported that he counted more than a thousand crossbowmen, but did not even bother to count the rest of the men armed with spears and pollaxes (BSH 5, p. 50). This testifies to the decreasing tactical importance of any mêlée weapons, and the ascent of the crossbow as the queen of the heavily forested Swedish theatre of war.

There is also a number of sources referring to the militia men as purely composed of crossbowmen (Skyttar). For instance, the militia of the Dalecarlia district which took part in the siege of Stockholm in 1501, was composed of 400 crossbowmen24. When the governors of the realm sent out letters in order to mobilize the militias, the crossbow was increasingly also explicitly stated as the sole mandatory armament of the militias. When the governor Svante Nilsson mobilized every fourth man in the realm in 1504, they should all be armed with crossbows and eleven dozen arrows each (GRÖNBLAD, nr 119). In Sweden, the later sixteenth century saw the formation of a permanent and regular army organization, but well into the reign of Gustav Vasa (1521-1560) the peasant crossbowman was the sentinel watching over the delicate Swedish independence in the recurrent wars against Denmark.

In the sources, each Swedish district (Landskap) is at some point mentioned to have mobilized a sizeable number of crossbowmen. Tentative calculations based on quotas of able men in relation to demographics shows that roughly 200 men could be raised from each sub-district (Härad). The total number in the realm must have been well beyond 10 000 men. However, the vast distances must often have made a quick mobilization difficult. The logistical challenge to assemble provisions for an army concentrated at one location, made it disadvantageous to call up more militia units than necessary. The meagre rural economy also prevented invading armies from bringing more men than necessary. The Danish kings seldom brought more than 4000 men to Sweden, which was the number that the Swedes had to match or preferably outnumber (NEUDING SKOOG 2016, p. 117-122). The last time a sizeable number of crossbow militia units were called up, were during the Dacke uprising (1542-1543). In February 1543, King Gustav Vasa stated that he had mobilized 7000-8000 crossbowmen in central and northern Sweden (GIR 1543, p. 93-94, 128, 629).

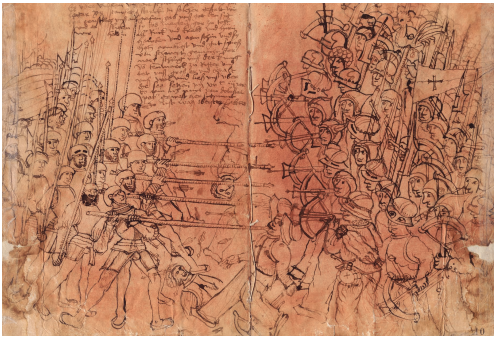

With some exceptions, the militia did not take part in naval operations (BSH 2, p. 94). On many occasions they took part in sieges, for instance, 3000-4000 militiamen besieged Stockholm in 1501-1502, and numbers of militiamen served at the prolonged siege of Kalmar (1503-1510) (SDHK, 34525;BSH 4, p. 197; BSH 5, p. 149; NEUDING SKOOG, 2018a, p. 385, 404, 484). Apart from frequent ambush tactics, the militia also fought a number of pitched battles, for instance at Brunkeberg (1471), Rotebro (1497), Brännkyrka (1518), Uppsala (1520) and Älvsborg in 1502, of which the last battle was commemorated by the German landsknecht Paul von Dolnstein in his famous drawings.

Fig. 3 At the indecisive Battle of Älvsborg, in July 1502, the militia of the Vestrogothia district (on the right hand) faced professional German landsknechte (left hand side). The effect of their arrows can be seen in the front rank of the German infantry. Drawing by the German landsknecht Paul von Dolnstein, who part-took in the battle (Thüringisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Reg. S, fol. 460 Nr. 6, Bl. 9v-10r)

Despite the problems of providing provisions, the militia units sometimes marched very far from their home districts. There are some indications that parts of the units were mounted, and accompanied by wagons, sleds or pack animals that carried the necessary provisions and munitions (NEUDING SKOOG, 2018a, p. 413-416; KLEMMING, 1866, p. 169-170; GIR 1543, p. 33). Every soldier was also instructed to bring 8-11 dozen arrows each (BSH 3, p. 24; GRÖNBLAD, nr 119). A few preserved statues instructs the men to bring certain amounts of flour, malt, beef or mutton, pork, fish, butter, cheese, grain, candles, empty barrels and petty cash (NEUDING SKOOG, 2018a, p. 405-407, 549).

The length of service for the militia units varied and ultimately depended on the access to provisions. The Crown demanded the units to bring provisions for 1-2 months, after which period the obligation to provide sustenance was transferred to the Crown. During prolonged operations, it was also common for the units to rotate, and to send replacement units as others returned home to tend to their farms (NEUDING SKOOG, 2018a, p. 393; SDHK, 33994). According to Sture krönikan, a thousand of Dalecarlia militiamen crossed the Baltic sea in 1496 to defend Finland, and in February 1511, the militia of Gästrikland was called up to defend Västergötland, situated about 350 kilometres away25. However locally organized, the Swedish militia certainly took part in operations all over the realm.

From the mid-sixteenth century establishment of a standing army in Sweden, there are frequent mentions of musters and exercise meetings. In late medieval times, the nobility was mustered yearly. For the militia, though, there are no records of musters or martial training in peacetime - only in wartime. Such a wartime muster in Värend in 1505, mentions how the nobleman Erik Trolle counted and inspected the thousand-strong militia, but this kind of information is especially rare in the source material (BSH 5, p. 50).

However, the organization would hardly function without training, and some scholars take it for granted that some periodic musters and exercise must have been carried out (ROSÉN, 1976, p. 288). If so, martial exercises were probably combined with social meetings. In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, local units of the standing army often exercised after church service on Sundays. This might also have been the case in earlier times. In the Swedish towns, «papegay» crossbow shooting contests with were integral parts of social life, as in Germany and Western Europe (ALM, 1947, p. 140-141). The 1520-s author Peder Månsson also claims that Swedish boys frequently practiced with both harquebuses, crossbows and bows. In the district of Dalecarlia, the custom was that young boys would receive no food unless they hit the practice target three times before supper (GEETE, 1913-1915, p. 128-129).

Also, during wintertime hunting would be an additional food source for the peasantry. Even though the aristocracy exclusively hunted elk and deer, crossbow skills came in handy when the peasantry hunted boar, roe deer, bear, wolf and small game such as squirrel. From a military point of view, the Swedish militia was by no means professional. During the period 1495-1525, however, warfare became near constant and we may assume that some of the militiamen became quite seasoned soldiers, albeit not professional in a military sense.

Aggregate comparison and conclusions

When we bring together and compare the different aspects studied in the Portuguese and Swedish cases respectively, a quite diverging result emerge. In terms of organization, the Portuguese militia had a permanent and explicit unit structure, with a regional organization based on the ‘Comarcas’ and with some degree of bureaucratization. Even though the Swedish militia war raised in a similar way each time it was mobilized, the organization clearly had a temporary character. It was locally organized and lacked a formalized unit structure and with no traces of bureaucratization. These differences clearly reflects the degree of royal power and capability of imposing recruitment policies over the entirety of each realm. Portugal defined its borders in 1249, and only 50 years later the «besteiros do conto» militia was created. Without any real prospect of territorial expansion at the time, the Portuguese Kings wished to better control the military recruitment within the kingdom, for the recurrent conflicts with Castile. The royal power consciously created the «besteiros do conto» as a mean of more effective war making and to ascertain control over territory. This step could hardly have been taken without a certain degree of state centralization. In Sweden, the early development is quite different, where the less bureaucratized and more autonomous militia can be seen as the result of the weak royal power and control over its subjects.

In Portugal, the militias had a permanent leadership with appointed professionals («anadel-mor», «anadel», etc.) within a fixed chain of command. In Sweden, in contrast, there was no fixed chain of command. The military leadership over the militias mirrored the social hierarchy, as various regional and local authorities (judges, bishops, bailiffs and noblemen) were expected to temporarily take up command. Why was there no formalized militia unit and leadership structure in Sweden, as in Portugal? The militia was certainly mobilized as often in Sweden. This might be connected to the weak character of the Swedish state paired with the political agency of the freeholder peasant communities. This seems to point to a clear difference is the relation between the military organization and the royal power. In Portugal, the organization of the «besteiros do conto» was originally commissioned by the king, and because of the forms of reimbursement it was largely dependent on royal power. In Sweden, the militia was constituted in the royal law, albeit vaguely as a general obligation to defend the realm. The royal power only had conditional access to the militia connected to promises of reimbursement, which made it largely independent. The Portuguese militiamen received individual pay and multiple privileges as well as collective tax exemption for their local communities. In contrast, the Swedish militia only received collective and temporary tax exceptions for their local communities, negotiated prior to each campaign. In some cases, when their regional political goals strongly aligned with those of the regent, they even seem to have fought without demands of reimbursement.

The reimbursement in ready cash in the Portuguese case, in contrast to Sweden, can probably be explained by the large degree of monetarization in Portugal, while an economy largely ‘in kind’ prevailed for long in Sweden. This does not, however, explain the contrasting individual and collective character of military service in each case. This might be connected to fact that the administrative management of the militia must have been easier in an urban setting, while the lack of bureaucracy in the decentralized rural Swedish society made individual contracting very difficult to administer.

The rural and urban character of the Swedish and Portuguese respective militias can easily be explained by the demographic and social structure of each society. The Portuguese militiamen were recruited in an urban setting and were prescribed to be married as well as house owners. In the largely rural Sweden, a seemingly heterogonous group of able men were recruited among the broader strata of peasants. There seems to have been a preference for unmarried men who increasingly came from the lower social strata. Why would only married men of some wealth be considered in the Portuguese militia, while the Swedes had their pic among all able men? The Portuguese strategy to recruit married men and house proprietors was probably a means to ascertain that the men lived continually in their respective urban center, and therefore the royal power knew in detail how many crossbowmen it could recruit in each region. It seems as if the urban-rural dichotomy as well as the degree of royal power, organizational capability and administrative penetration into local society, in each case, makes up for most of the differences apparent in the comparison.

In terms of performance, the Portuguese militia was an elite force within the peonage, composed of men permanently assigned as crossbowmen and with some degree of military professionalism. In Sweden, the militia was non-professional - even though sometimes experienced from frequent campaigning - and the military service seems to have rotated among the men in local society. In terms of martial impact, the more general and collective character of the Swedish militia organization - in contrast to the more individual and selection-oriented character of the Portuguese system - arguably generated a broader military impact on Swedish society as a whole, than it did in Portugal.

The purpose of this paper has been to study late medieval militia organizations by means of comparison. Even though we chose two quite neatly separated cases to compare, the overall aim has not been to try to discover any universal similarities about the essence of medieval militias. The scholarly pursuit to find analogies only really give us very broad conclusions about medieval European society in general. This comparison rather highlights striking and interesting differences. The methodical benefits come from the mirroring of the cases, where we have identified aspects peculiar to each case. In national history writing, the characteristics of age-old military organizations are often taken for granted. What seems uncontroversial or odd in a single case, however, may be contested or accentuated through a comparison. The results thus highlighted forces the historian to explain differences as well as similarities.

The comparison emphasizes how the two Kingdoms traced different chronological paths. The Portuguese militia rose to prominence already during the late 13th century - much earlier than its Swedish equivalent, which emerged as a significant military factor during the 15th century. Interestingly however, both countries eventually rose to imperial status. In each case, the militia organizations functioned as models or precursors of subsequent recruitment systems, which provided military personnel for expansive enterprises in each realm.

The difference in timing of the respective ‘imperial leaps’ is connected to other differences in geography, changing geopolitical conditions as well as internal political structures and the military history of each realm. Despite the different chronologies, we have been able to present a structurally coherent study where the where and why becomes more important than when. Apart from a purely military point of view, the study of medieval militia organizations clearly also helps to illustrate the political, social and economic character of each particular society that organized them.