Introduction

Looking at forty years of elections for the European Parliament (EP), one of the most striking phenomena that took place is the constant growth of populist parties in terms of their overall number, electoral performance, and number of seats they occupy. This phenomenon is not particularly surprising since populist parties grew also in national elections during the same period, but it is significant because their growing influence poses serious questions about the European Union (EU), its common identity, its principles, and its future. This is the case for two main reasons: first, populism challenges liberal democratic principles and the rule of law (Abts & Rummens, 2007) and second, because populist parties have become mostly Eurosceptic (Treib, 2021). In other words, the growing presence of populist parties in the EP might bring to a substantial transformation of the European institutions, or even to a collapse of the entire political system on which the European Union has been built.

The 2019 elections that brought to the formation of the ninth EP have been framed as a battle between populist, Eurosceptic parties and liberal, pro-European forces (Noury & Roland, 2020). The structure of competition that characterises the EP elections is increasingly based on trust or distrust toward the EU, a division that has become more salient than the left-right cleavage that used to dominate the elections for the EP (Hix, Noury, & Roland, 2005, 2007). This new, transnational cleavage (Hooghe & Marks, 2018) constitutes the main dimension of politics (Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier, & Frey, 2006, 2008) and certifies the importance of populist forces within the EP, because they channel the votes of citizens that distrust the EU.

By 2019 it became undeniable that Eurosceptic parties have established themselves as a permanent and relevant feature of the EU party system (Treib, 2021), a transformation reflecting the growing discontent of citizens towards the EU (Dijkstra, Poelman, & Rodríguez-Pose, 2020). The fact that pro- or anti-EU positions constitute a relevant axis of competition (Hix, Noury, & Roland, 2007) might represent an advantage for populist parties that build their electoral campaign on a more or less strong Euroscepticism (Heinisch, McDonnell, & Werner, 2021), because their Euroscepticism distinguishes them from mainstream, pro-EU parties. Indeed, populist parties usually adopt a position that, with varying degrees of emphasis, describe the EU as an undemocratic level of governance led by bureaucrats and supranational elites that have no accountability, in a narrative that opposes the interests of the common people to those of distant institutions.

This critique is not necessarily problematic, because in a pluralist vision of Europe it is important that critical voices can raise legitimate questions about the current state of democracy and propose possible improvements on the institutional framework of the EU: treating populist parties simply as the expression of an irrational impulse would be a mistake (Kaltwasser, 2014). Complex policy initiatives - such as the governance structure of the EU - are perceived as lacking legitimacy and accountability: the populist reaction to this shortcoming of representative politics should not be dismissed but rather taken into consideration (Kaltwasser, 2012). At the same time, it is undeniable that the growing importance of populist parties within the EP - and in particular of populist radical right (PRR) parties2 - challenges core principles of the EU such as rule of law, media freedom, separation of powers, and equality, as exemplified by the conflict between Hungary and Poland against the rest of the member states on such issues (Closa, 2020; Soyaltin-Colella, 2020), to the point that Poland and Hungary have recently filed a complaint with the EU’s supreme court over a mechanism that ties respect for the rule of law with EU funding.

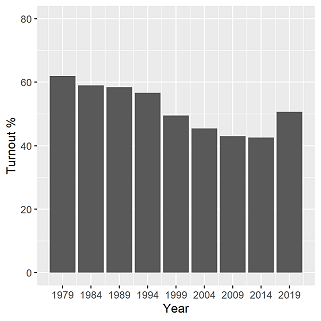

The paper describes the growth of populist forces within the EP over time, covering forty years (1979-2019) and nine elections. This diachronic perspective offers an overview on the development of different types of populist parties in what are often considered as second order elections (Reif & Schmitt, 1980). This means that the EP elections are normally a favourable ground for populist parties, since they tend to yield lower scores for mainstream parties and higher scores for protest parties, together with a lower voter turnout3. However, the fact that some populist parties are increasingly achieving positions of power in their respective countries (Albertazzi & McDonnell, 2015), combined with the fact that the turnout for the 2019 elections has been the highest since 1994 (Figure 1)4, suggest that in the future the elections for the EP might become first order elections. Moreover, the long-dominant and pro-EU groups European People’s Party (EPP) and Socialists and Democrats (S&D) lost their combined parliamentary majority for the first time in EU history, producing a fragmented parliament (Mudde, 2019a), a fact that could have unforeseeable consequences for the stability of the EU.

The populist wave that some commentators predicted before the 2019 elections did not materialize, and populist parties were not able to gain almost half of all seats in the European Parliament as some anticipated5. However, this does not mean that populist parties and their Euroscepticism are irrelevant for the future of the EU. The fact that almost a third of the seats of the EP have been assigned to populist parties, most of which oppose to some degree the current institutional framework of the EU, should not be overlooked. In fact, it could have relevant implications, especially because populist radical right parties are increasingly willing and able to organise themselves in political groups and exert their influence in a coordinated way within the EP.

The paper is structured as follows. First, it presents the results of populist parties over time, in order to contextualise the performance of populist parties in EP elections and correctly understand their growing influence. It shows how in the first EP, elected in 1979, was present only one populist party, while 32 populist parties were elected in the ninth parliament, elected in 2019, occupying almost 30% of the available seats. The following section addresses the issue of political groups within the EP, focussing only on right-wing populist parties. Once again, a diachronic perspective that focuses on particularly relevant cases, offers the possibility to observe how in the past the political groups formed by right-wing populist parties were riddled with divisions and often short-lived, but also that this situation is changing. Building on the two previous sections, the paper presents three distinct phases of populist parties in the EP: growth and consolidation (1979-1999), populism as the “new normal” (2004-2014), and finally it suggests that from 2019 there has been a paradigm shift, marking the beginning of a new era in which populism seriously challenges non-populist forces within the EP. The final remarks discuss the implications of the populist growth in the EP and possible future scenarios.

1. Populist parties in the European Parliament

Populist parties have been in the EP since it was elected for the first time in 19796. The first populist party to be elected in the EP was the Progress Party, a Danish right-wing populist party founded in 1972 and particularly successful in the 1970s, which however never managed to be elected in the EP again. This section presents the history of populist parties in the EP from the single seat occupied by the Progress Party to the 2019 elections, when 32 populist parties were elected in the ninth parliament, taking almost a third of the available seats. First, however, it is necessary to provide a definition of populist parties, on which it will be based a distinction between right and left-wing populist parties, as well as valence populist parties. Then, it is discussed the performance of different types of populist parties in the nine elections of the EP between 1979 and 2019.

Given that the main focus of this work are populist parties in the EP, it is necessary to start by clarifying that populism is here understood as an ideology (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, 2017a), certainly not the only definition available but one that has been employed by a large amount of researchers on the topic (Hawkins & Kaltwasser, 2017a). Populist parties emphasize the moral distinction between the “pure people” and the “corrupt elite” while glorifying “popular sovereignty” (Mudde, 2004), and being a thin ideology populism can be combined with any other full ideology, such as communism, ecologism, nationalism or socialism (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2012). For the classification of populist parties according to their ideology, we use two sources that rely on the same definition of populism adopted here. First, the data provided by the PopuList (Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde, & Taggart, 2020), which distinguish them between populist and non-populist parties, but also classify them as far right, far left, and Eurosceptic7. Second, we build on a recently published dataset (Zulianello & Larsen, 2021) that provides the number of seats obtained by populist parties in the EP, categorizing them as right-wing (with an extra category for the radical right), left-wing, or valence.

Here it is necessary to introduce a clarification about the nature of valence populist parties, which include parties such as the Czech ANO 2011 and the Italian Five Star Movement. This is a family of populist parties that was created to respond to the necessity to categorize those parties that do not clearly belong to the right or to the left, without being centrist. These parties are clearly populist, and often they are mostly just populist, they insist on non-positional issues such as corruption, morality, and democratic regeneration (Zulianello, 2020), and might appeal to technocratic solutions. Their ideology is focused on a “pure” form of populism in isolation rather than in combination with other ideologies, making their policy positions flexible and adaptable (Manucci & Amsler, 2018).

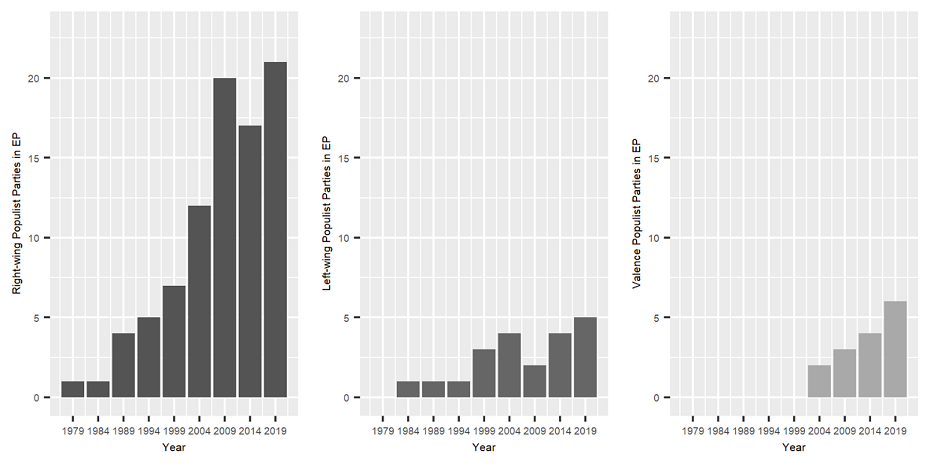

Figure 2 presents the overall performance of populist parties in the EP between 1979 and 2019, expressed as percentage of the seats they obtained8. As the figure illustrates, populist parties have been growing constantly within the EP, and only on one occasion their share of seats diminished compared to the previous election. In nine elections a total of 92 populist parties gained representation, of which 61 are right-wing (often populist radical right), 16 are left-wing and 15 are valence (Zulianello & Larsen, 2021). Since the first election of the EP in 1979, populism gained representation: the first populist party to be elected in the EP was the Danish Progress Party, obtaining just one seat that constituted 0.24% of the total 410 seats.

The populist presence grew considerably already in the second (1984) and third (1989) EPs. In 1984 the National Front (FN) and the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), respectively a French radical right and a Greek left-wing populist party, obtained 10 seats each, bringing the populist representation to 4.6% of the available seats.9 In 1989, when Spain and Portugal participated at the elections for the first time, the percentage of seats remained stable (5.4%), but the number of populist parties grew from 2 to 5: one left-wing (PASOK) and four right-wing populist parties. Of these four, only one at the time was not radical (the Italian Lombard League), while the other three were radical: Flemish Block (Belgium), National Front (France), The Republicans (Germany).

In the 1990s, the presence of populist parties in the EP first grew quickly, but then slowed down. In 1994, the percentage of seats for populist parties doubled compared to the previous elections, arriving at over 10%. However, in 1999, this number went back to 8.1%, when for the first (and so far, last) time, the percentage of seats in the EP occupied by populist parties decreased. 1994 marked the first EP elections since enormous political upheavals such as the end of the Cold War, the German reunification, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the Treaty of Maastricht that established the European Union. PASOK remained the only left-wing populist party in the EP, and the first Eurosceptic group was created (Europe of Nations), without any populist party involved. In 1994, Berlusconi’s party Forza Italia gained 30.6% of the vote share as well as 27 seats at its first participation in European elections. In 1999, after the enlargement to include Austria, Finland, and Sweden, the turnout for the first time went below 50%, and while the number of populist parties increased to 10, the percentage of seats they occupied decreased (8.1%). Left-wing populism managed to obtain representation with three parties from Greece, the Netherlands, and Germany, occupying a total of 9 seats.

Since the 2000s, the percentage of seats occupied by populist parties has started to grow again and has remained constantly in double digits. In 2004, right after the enlargement to 10 new countries, 18 populist parties were elected in the EP and obtained almost 13% of the available seats. Moreover, valence populist parties made their first appearance in the EP (Figure 3)10, with the Hans-Peter Martin’s List in Austria (1 seat), and the Labour Party in Lithuania (5 seats). In 2009, populism became even more widespread, with 25 parties obtaining almost 18% of the seats.

Left-wing populism followed the opposite trend, with only two parties present in the EP (The Left from Germany, and the Greek SYRIZA). Right-wing populist parties, on the other hand, almost doubled, passing from 12 to 20 with 112 seats (more than 15% of the whole EP), while Bulgaria managed to bring into the EP two valence populist parties that joined the Hans-Peter Martin’s List for a total of 10 seats.

In the 2010s the growth of populist parties continued, with percentages of total seats well beyond 20%: 23.2% in 2014 and almost 30% in 2019. In 2014, the total number of populist parties remained stable at 25 compared to 2009, with right-wing populists decreasing for the first time (from 20 to 17, Figure 3) while left-wing and valence populist parties grew from 2 to 4 and from 3 to 4 respectively, for a total of 21 left-wing populist seats and 28 valence populist seats. In 2019, the voter turnout was higher than 50% for the first time since 1994, while the European People’s Party (EPP) and Socialists and Democrats (S&D) lost their combined parliamentary majority for the first time in EU history, producing a fragmented parliament. The 2019 elections represented the highest share of seats for populist parties (29.96%), as well as the highest number of populist parties of each type (21 right-wing, 5 left-wing, and 6 valence).

The next section illustrates, following a similar diachronic approach, how right-wing populist parties initially struggled to organize themselves in political groups within the EP, but ultimately managed to form large and influential groups of Eurosceptic, populist, radical right parties.

2. The difficult art of finding common ground

This section analyses how right-wing populist parties managed to form groups within the EP over time. The focus is on right-wing populist parties for several reasons: first, because they constitute a majority of all populist parties; second, most of them are also radical and Eurosceptic (Zulianello & Larsen, 2021; Rooduijn et al., 2020), therefore they pose the biggest threat to the EU and its core values; third, because given their continuous growth over time and their current success, they could realistically become a majority within the EP in a not-too-distant future. Participating in the EP is very important for right-wing populist parties - and for populist radical right (PRR) parties in particular - because they gain legitimization, which in turn can improve their electoral performance (Eatwell, 2003) while political representation in Strasbourg guarantees resources and patronage (Norris, 2005).

Moreover, there is another level: not only being represented in the EP is important, but also forming alliances and political groups within the EP is crucial to amplify a party’s message. For several reasons, right-wing populist parties traditionally struggled to form political groups, which in turn made them less visible to the public, less funded, and less influential. The way in which right-wing populist parties manage to organize themselves and form political groups in the EP is significant because - beyond their individual electoral performance and seats gained - it offers them the possibility to increase their visibility and influence. This is the case because forming political groups grants practical advantages, such as resources for political campaigns, financial and administrative resources, as well as the visibility offered by extra speaking time (Whitaker & Lynch, 2014).

Right-wing populists traditionally struggled to form groups in the EP. When they have not been isolated among the parliament’s non-inscrits11, they only managed to form small, short-lived, ideologically heterogeneous groups, marriages of convenience that allowed them to secure funding (Mcdonnell & Werner, 2019). Until recently, the predominant view was that PRR parties - the overwhelming majority of all right-wing populist parties - could not form stable groups because of their conflicting nationalist agendas. Moreover, mainstream parties have been traditionally afraid of forming alliances with right-wing populists and especially with PRR parties, because they were afraid that being associated with parties that are perceived as too extreme might damage their image at the national level (Fieschi, 2000; Minkenberg & Perrineau, 2007).

Analysing the evolution over time of their ability to form political groups makes clear that right-wing populist parties are now in the position of forming large, influential groups in the EP. Right-wing populist parties, and in particular PRR parties, can now form groups out of policy congruence rather than pure opportunism, and the days of their structural fragmentation are over. This section presents the history of three specific political groups formed by right-wing populist parties over time, and compares their failures to the current situation, in which PRR parties control two large and influential groups within the EP.

2.1. Group of the European Right (1984-1994)

The first populist radical right party to ever be elected in the EP was the French National Front (FN) in 1984. Under the initiative of its leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, the FN promptly formed the Group of the European Right (GER) together with members of the Italian Social Movement (MSI) and the Greek National Political Union (EPEN), two far right, nationalist, but not populist parties. They managed to gather a total of 16 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), that became 17 when, in 1985, they were joined by John Taylor, of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP). At the 1989 elections, however, this group did not manage to confirm its composition. The reasons behind its failure are particularly interesting, because they influenced a long-lasting idea concerning the inability of right-wing populist parties to form political groups in the EP.

Despite the loss of the Irish UUP and Greek EPEN members, who were not re-elected, the 1989 European elections afforded the opportunity for the expansion of the Group of the European Right with the election of six MEPs from the German Republicans (REP) as well as two Italian Northern League (LN), and two Belgian Flemish Block (VB) representatives (Startin, 2010). However, the MSI decided not to participate in the group for two reasons: first, because of the disagreement with the Republicans, who supported the claims on South Tyrol expressed by the separatist Die Freiheitlichen (Bartolini, 2005), an unacceptable position for a party that insisted on the Italian national unity such as the MSI; second, the new leader Gianfranco Fini wanted to appear more moderate than his predecessors and feared that the stigmatising effect of an alliance with the FN, still fully diabolisé (Mayer & Perrineau, 1996), would have harmed the party’s path towards less extreme and more mainstream positions.

As a consequence, the group was renamed Technical Group of the European Right (TGER) and was composed once again by German REP, Belgian VB and French FN members, with Jean-Marie Le Pen as its chair. However, it was a purely technical group and continuous conflicts among its members made it almost impossible to advance a concerted action (Fieschi, 2000). Moreover, as it was already the case for its predecessor, the TGER did not have access to the normal channels for cooperation nor did it gain any committee chairs (Startin, 2010). Finally, when at the 1994 elections the Republicans failed to reach the 5% cut-off point for German elections and lost all their MEPs, the TGER no longer had the numbers to qualify as a group and its MEPs returned to the ranks of the non-inscrits, without the privileges and funding that groups can access.

2.2. Technical Group of Independents (1999-2001)

A second example of the difficulties that right-wing populist parties used to face when trying to organize themselves and form groups within the EP consists in the short-lived Technical Group of Independents (TGI). Like the TGER, also the TGI was a technical group without a clear unity in terms of policy goals, to the point that its turbulent existence was at the origin of the European Court of Justice’s decision to forbid overtly mixed groups without a coherent political agenda. Indeed, this was not a group of just right-wing populists (National Front, Northern League) or far right - non-populist - parties (Flemish Block, Social Movement Tricolour Flame): to reach the requirements to form a group they also involved a party that is neither populist nor right-wing: the Bonino List, indeed, was the expression of the Italian ultra-libertarian, anti-statist Radical Party (Startin, 2010). This shows how, for a long time, right-wing populist parties struggled to form alliances in the EP and had to include heterogeneous partners, and in this particular occasion the refusal of the Danish People’s Party and Freedom Party of Austria to join Le Pen proved to be an insurmountable obstacle.

The fact that it was a technical and not a political group brought other MEPs to question its legitimacy because political affinities within groups were already a requirement at the time (Fieschi, 2000). Just a few months after the 1999 elections, the TGI was dissolved by the parliament. Although after this decision it was briefly readmitted, it was then dissolved for a second and final time in October 2001. This short-lived group is interesting for two reasons: first, it shows the difficulties of right-wing populists to cooperate and form coherent groups within the EP; second, after this singular and troubled experience, mixed groups were no longer allowed to be formed in the EP thanks to the Rule 29 on the “Formation of political groups, of the Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament”12. Interestingly, in the same period, the EU institutions tried to prevent the radical Freedom Party of Austria from joining the country’s government, threatening Austria and de facto imposing a cordon sanitaire around the populist radical right (Heinisch, 2004), confirming that the cooperation between these parties was not only difficult because of their conflicting national interests, but also because of the techniques adopted to marginalize them.

2.3. Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty (2007)

In 2007, following the enlargement of the EU to 27 member states that allowed the Bulgarian Attack and the Romanian Greater Romania Party (PRM) to be elected in the EP, 20 MEPs from seven different countries formed the group Identity, Tradition and Sovereignty (ITS). Prior to the accession of Bulgaria and Romania the right-wing populists had lacked sufficient numbers to formalize their cooperation and form a group.13 Following a pattern that we already observed for the two previous groups, the core members of ITS came from the FN and the VB, joined by Social Alternative (a spin-off of the same MSI that previously joined FN and VB14 in political groups within the EP, founded and led by Benito Mussolini’s granddaughter Alessandra Mussolini).

The group was extremely short-lived and lasted only the few months between its creation in January 2007 and its dissolution in November of the same year. At the time, the media insisted that the main reason behind the group’s end was the fight between Alessandra Mussolini and the MEPs of the Romanian PRM. The members of the PRM felt insulted by the remarks of Mussolini, who declared - among other things - that law-breaking had become a way of life for Romanians. However, they did not leave the group because of this, but rather because after the November 2007 elections in Romania, the PRM obtained 4.15% of the votes, falling below the 5% cut-off. As a consequence, the ITS did not have the minimum number of MEPs and failed also to reach the amount of representatives from different countries to qualify as a group. Moreover, Nicholas Startin claims that the marginalization of the group has to be attributed also to two other factors: on the one hand, the fact that the EP decided to implement “a transnational cordon sanitaire”, and on the other hand “the strength of European media hostility” (Startin, 2010, p. 440). As a result, yet another attempt of the leaders of the populist right across Europe failed to materialize into a stable group in the EP.

2.4. Identity & Democracy, European Reformists and Conservatives (2019)

In the period 2009-2014, the group Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) assembled right-wing populist parties such as the UK Independence Party, Danish Peoples’ Party, the Finns Party, and the Northern League (Italy). In the following parliament (2014-2019) the group was then renamed Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD): although some of the previous members left, the group was formed thanks to the inclusion of new parties such as the Italian Five Star Movement, Sweden Democrats, and Party of Free Citizens (Czech Republic). When Nigel Farage’s UKIP, traditionally the group member with most MEPs, left the EP after Brexit, EFDD was dismantled. Some parties decided to be non-inscrits, others failed to be elected in the EP after the 2019 elections or decided to join other groups. However, the end of the EFDD group did not mark the end of the possibility for right-wing populist parties to organize and form groups: to the contrary, following the 2019 elections, right-wing populist parties managed to form two groups, strong of their numbers. In the ninth parliament, were elected 21 right-wing populist parties, which managed to occupy 171 seats (142 since the Brexit Party left the EP with its 29 MEPs)15.

Whether we consider the pre- or post-Brexit numbers, the impact of right-wing populist parties in the ninth EP is considerable: 21 parties occupied 22.8% of the total seats before Brexit, and after the Brexit Party was no longer in the EP, they still occupied more than a fifth of the seats (20.14%). While the electoral performance of right-wing populist parties is already remarkable per se, as described in the previous section, the ninth EP is characterised by the unprecedented capacity of right-wing populist parties to form stable, influential groups based on common policy goals. Contrary to previous elections, virtually all right-wing populists joined a group of like-minded parties, with only four exceptions: one decided to be among the non-inscrits (the Hungarian Jobbik), while three joined the mainstream EPP group: the Slovenian Democratic Party in coalition with the Slovenian People’s Party, Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, and Fidesz, although the latter left the group in 202116.

In the ninth EP, for the first time in forty years, there are two distinct political groups that include exclusively parties that can be characterised as Eurosceptic, populist, and radical right17. The first of these groups is Identity and Democracy (I&D), successor to the Europe of Nations and Freedom group formed during the eighth term, and includes, to name just a few: Freedom Party of Austria, Flemish Importance (Belgium), Danish People’s Party, Finns Party (PS), National Rally (France), Alternative for Germany, League (Italy), and Party for Freedom (Netherlands)18. With 76 MEPs, Identity and Democracy controls 10.8% of the seats in the EP, which makes it the fourth biggest group in the current parliament. The other group technically is not new, because it is present in the EP since 2009: the European Reformists and Conservatives (ECR). Reflecting the progress of PRR parties across the continent, the ECR group is now entirely composed of Eurosceptic, populist, radical right parties, exactly like the I&D group, while this was not at all the case in previous occasions. The biggest party in the ECR is Law and Justice (Poland), and other member include Vox (Spain), Forum for Democracy (Netherlands) and Brothers of Italy, to name just a few. With 62 MEPs, the ERC controls 8.8% of the total seats in the EP. In the eighth parliament (2014-2019), the ECR and I&D (as already mentioned, at the time I&D was called Europe of Nations and Freedom) were already important, controlling together 15% of the seats, while now they are beyond 20%. Not only Eurosceptic, populist, radical right parties gained many seats in the EP over time, but they also managed to organise themselves in groups.

3. Three phases of European populism

3.1. 1979-1999: growth and consolidation

The first five elections of the EP can be grouped together, as they represent a first phase of populist presence marked by progressive growth and consolidation. This phase started in 1979 - with only one party and one seat - and concluded in 1999 - with 10 parties from 10 different countries and 8.15% of the available seats. During this phase, populism passed from being a marginal presence to a widespread feature of European politics in general, and the EP in particular. However, compared to following phases, the growth of the influence of populism has been irregular. Indeed, given the exploit of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia in 1994, the 1999 elections saw a contraption of right-wing populists’ influence given that they lost almost 2% in terms of seats. This is linked to the anomaly represented by the Italian situation in 1994: a mix of international factors and the complete restructuring of Italian politics after the corruption scandal known as “Bribesville” (Bull & Rhodes, 1997), made it possible for Forza Italia to obtain 27 seats, when all the other five populist parties together had 30 seats.

In this initial phase, compared to the following ones, it can also be noted the total absence of valence populism, partly because at the time these parties were less common and partly because the countries that more commonly display them, mostly in Central and Eastern Europe, were not part of the EU at the time. Moreover, until 1994 the only left-wing populist party in the EP was the Greek PASOK, meaning that in this first phase right-wing populism was almost the only type of populism represented in the EP. Moreover, at the time the European institutions deployed several tactics to marginalize the radical right. The tendency for the EU to make moral judgments about the radical right and to impose an EU-wide style cordon sanitaire was clear when the EU deployed tactics designed to marginalize technical groups of far-right parties that existed between 1984 and 1994 (Startin, 2010). Another obvious example of this was the decision of the EU to impose diplomatic measures against the Austrian coalition government in which Jorg Haider’s Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) was the junior partner in government following the 1999 general election (Fallend, 2004).

In this phase, right-wing populist parties tried to establish political groups within the EP as discussed in the previous section, with the European Right formed by Le Pen being possibly the most successful of them. However, in this phase right-wing populist parties mostly struggled to form political groups in the EP: the groups formed by right-wing populist parties were often of a technical nature, hampered by the EU, or disrupted by other factors. Interestingly, the most openly Eurosceptic group formed in this phase, Europe of Nations and Diversity (1999-2004), did not include any populist party. This is peculiar, because in recent years most populist parties are Eurosceptic and vice versa.

3.2. 2004-2014: populism as the new normal

The first three EP elections of the 21st century can be grouped together because the success of populism could no longer be ignored or managed through a cordon sanitaire. In this phase, populism became the new normal: it passed from being an exotic beast to becoming a regular feature of the EP. During this time, populist parties at the national level obtained increasing favourable results, and this was reflected also in their growth within the EP. Between 2004 and 2014, populist parties almost doubled their seats in the EP, going from 12.8% to 23.17% of the total. Populist parties regularly performed in double digits in many EU countries, with a particularly high support in new member states such as Hungary, Bulgaria, and Poland (27.8%). For this reason, the two enlargements of 2004 and 2007 that brought 12 additional countries in the EP were crucial in the normalization of populism, and the fact that it became a mainstream phenomenon (Mudde, 2019b). As a result of the enlargements, it is possible to also notice the arrival of valence populist parties, a phenomenon that characterises especially Central and Eastern Europe.

In this phase, populism is present in all its variants, and contrary to what we can observe for 2019, right-wing populist parties at this time were not necessarily radical. To explain this trend, we can compare the 2019 elections with the three elections that took place in this phase: in 2019, 18 of the 21 right-wing populist parties present in the EP were radical, meaning 85.5% of right-wing populism is now radical. In 2004 only 6 out of 12 right-wing populist parties were radical (50%), in 2009 12 out of 20 (60%), and in 2014 9 out of 17 (52.9%)19. If in the previous phase populist parties were a marginalized phenomenon, between 2004 and 2014 they have managed to become a nationwide, and even transnational phenomenon (Wodak, 2015).

As mentioned in the previous section, in this phase right-wing populist parties formalized their cooperation in political groups more easily than before, and their impact and influence on the European institutions grew considerably. Europe of Freedom and Democracy (2009-2014) and its successor Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (2014-2019), together with Europe of Nations and Freedom (2015-2019), brought right-wing populist parties together in large and influential groups. With 20 countries having at least a populist party and almost a quarter of the total seats available, the eighth EP (2014-2019) marked the peak of a process of transformation of populist forces into normal, often mainstream parties that are no longer considered as undemocratic rascals, but well integrated political actors.

3.3. 2019: a paradigm shift?

Compared to the eight previous EP elections, the ninth stands out in several ways, to the point that it is possible to consider it as the beginning of a new phase characterised by a paradigm shift, with populism reaching a new status within the EP. First, the 2019 EP elections clarified that populist parties realistically threaten the hegemony of mainstream parties of the pro-EU European People’s Party (EPP) and Socialists and Democrats (S&D). In particular, it is a specific type of populist parties that can challenge the mainstream: radical right, Eurosceptic, populist parties. Second, to compete with populist forces, mainstream parties seem to have followed a process of radicalization (Mudde, 2019a), with the result that far right ideas have been normalized. Third, every type of populism is growing across the whole continent, even in countries that were previously considered to be ‘immune’ because populist attitudes were not activated (Hawkins, Kaltwasser & Andreadis, 2018).

In 2019, when the turnout has been the highest since 1994, a record number of 32 populist parties were elected in the EP, obtaining the highest percentage of seats in the 40-years-long history of the EP: 29.96%20. Every type of populist party achieved the best result in the EP history: 21 right-wing populist, more than the previous record set in 2009, obtained 22.77% of seats; 5 left-wing populist parties obtained representation (3.19% of the seats), more than in 2004 and 2014 when they were 4, through the elections in France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, and Spain; valence populism parties also achieved their best result ever, with 6 parties gaining representation (4% of the seats), a phenomenon that characterizes Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia) as well as Italy.

Concerning only right-wing populist parties, a significant change in their characteristics has to be stressed: in 2019 they were almost exclusively radical and Eurosceptic. Of the 21 right-wing populist parties that were elected in the EP after the 2019 elections, indeed, 18 are classified as radical right (Zulianello & Larsen, 2021), and 19 as Eurosceptic (Rooduijn et al., 2020)21. While this is an important fact per se - because populist parties can realistically become a majority within the EP - it also entails a deeper and even more challenging transformation of the political space within the EP: trying to remain a majority, some mainstream parties chose to follow a process of radicalization that in certain cases made them undistinguishable from PRR parties. For example, as observed by Cas Mudde, mainstream parties now openly discuss immigration and multiculturalism as threats to national identity and security (Mudde, 2019a), although it has been observed that fighting radical right parties by copying them is a losing strategy (Van Spanje & Graaf, 2017). This situation is the result of a process that characterised the years before the 2019 elections, when a growing number of right-wing populist parties chose to take a nativist turn, and can now be classified as PRR, including Fidesz in Hungary and Law and Justice in Poland (McDonnell & Werner, 2019).

Finally, it is worth noticing that 2019 marked the beginning of a new trend with right-wing populist parties electing representatives in the EP also in countries previously considered ‘immune’ . Considerable gains to right-wing populists occurred in countries where PRR parties were previously weak, for example Sweden (9.7% in 2014; 15.3% in 2019), Germany (from 7.1% in 2014 to 11% in 2019), Estonia (from 4% in 2014 to 12.7% in 2019), and Spain (from 1.6% in 2014 to 6.2% in 2019). While PRR parties tried to cooperate and form political groups not only based on ideological conviction but also out of tactical necessity (see, for example, the TGI group discussed above), this is changing because there are enough parties with a similar agenda and policy goals to form not only a group of like-minded forces like the group Identity and Democracy (I&D), but also to “colonize” a more established group like the European Reformists and Conservatives (ERC). Combined, these two groups composed of parties that are at the same time populist, radical right, and Eurosceptic, control almost 20% of the available seats in the EP.

Conclusions

The story of populism in the European Parliament mirrors the story of populism across the EU member states in the last four decades and shows that populism is no longer an exception: it moved from the fringes to the mainstream. The EPP group in the EP recently changed its rules in order to be able to expel Fidesz, the party of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban. Fidesz decided to leave the EPP right before being expelled, but the problems posed by this conflict will characterise the relationship between the European Union and PRR parties in the next years: where to draw a line between the EU core values and the authoritarian, illiberal tendencies that parties like Fidesz promote?

At the same time, the EU has to face another challenge: its lack of democratic credentials in the eyes of the people. The EP is the only directly elected institution of the EU, therefore the powers that the parliament will have, and the ways in which it will incorporate the populist critique, will largely determine its credibility. The fact that in 2019, for the first time since 1994, the turnout was higher than 50% means that the European citizens are interested in what happens in the EP, and that possibly certain issues, such as the role of the EU, have been re-politicized. After decades in which Europeans were simply asked whether they wanted to be part of the EU but not what kind of EU they would have liked, the success of populist parties indicate that this way is no longer viable if the EU wants to be perceived as something more than a technocratic, elitist level of supranational governance. Following in every aspect the critique posed to the EU by PRR parties, however, cannot be the solution: these parties, when in power, are responsible for the backsliding of democracy and the rule of law in their respective countries, and the EU has to react in a quicker and more cohesive way in these cases (Kelemen, 2017).

The other lesson we can learn by observing forty years of EP elections is that 2019 seems to mark the beginning of a different era for three different reasons. First, some mainstream right-wing parties decided to adopt the nativism and authoritarianism of PRR parties. In this way, the ideas of the radical right, that before were marginalized, are now at the very centre of the political debate within the EU: they have been mainstreamed and normalized, while for decades they were ostracized and relegated to the margins. Second, PRR parties are increasingly successful also in countries that were considered “immune”, such as Germany, Sweden, and Spain. Third, although in a much smaller scale compared to PRR parties, also left-wing and valence populist parties are growing across Europe and gaining an increasing space within the EP.

Crucially, PRR parties showed that they are able to form groups within the EP, formalizing their cooperation and proposing a more or less coherent opposition to the EU from within its institutions. This has several implications for democracy in Europe. Even if mainstream parties will start fighting PRR parties with different policies instead of assimilating them, it is not clear whether they will manage to retain a majority in the EP. The two mainstream, pro-EU European People’s Party (EPP) and Socialists and Democrats (S&D) lost their combined parliamentary majority for the first time, and this could now become the ‘new normal’. If populist, Eurosceptic parties will fill this gap it is unclear what kind of Europe could emerge from the decisions of parties that have made it abundantly clear that they do not like Europe as it is, parties that when they do not want to abolish the EU, they certainly wish to radically reform it.

Non-populist parties could choose to become increasingly populist themselves and copying the authoritarian and nativist policies proposed by PRR parties, or listen to the critiques formulated by parties that want to change Europe and its institutions. If they refuse to listen, or if they decide not to act to introduce changes, the voice of Eurosceptic MEPs might de-legitimize the EU among citizens and thus indirectly contribute to stalling the integration process (Diez Medrano, 2012). However, it is also possible that the presence of dissenting voices could increase the representativeness of the EP, and contribute thereby to the legitimacy of the system (Brack, 2013). The future of European democracies is strictly linked to the tension between populism and liberal democracy: the EU might become increasingly illiberal and authoritarian, following the growing influence of PRR parties, but it can also choose to become more democratic and transparent, listening to the populist critique to reform itself according to its core values such as rule of law, separation of powers, freedom, and equality.