1. Introduction

Our deliberations are primarily intended for those researchers who want to try their hand at implementing their own research projects using applications from the CAQDA family. In their case, it may be a good idea to use free software distributed under the GNU license (General Public License). Although these programs are usually not so rich when compared to the software versions (Richards, 1999; Saillard, 2011), as they do not have such extensive features or they offer a less user-friendly working environment (among others due to the graphic design of the program which differs from current trends), most of them pose a great alternative for those still relatively expensive and thus not so commonly available paid applications (Niedbalski, 2014; Niedbalski & Ślęzak, 2016; Niedbalski & Ślęzak, 2012).

Our intention was primarily to present free tools, commonly available through websites and fully functional, i.e., without any restrictions imposed by their publishers or authors. We have decided that this way a user receives a program that can be used in their research, without any further restrictions. Regardless of the amount of the materials they want to analyze with this application, they can do so for an unlimited time, and what is more - they do not need to bear any financial costs (Niedbalski, 2013). However, we are aware that it would be impossible to present all such programs, hence the need to select and choose some of them. The reasons these and no other programs are in our research are explained below. At the same time, we would like to emphasize that a methodological reflection presenting a relationship between the computer-aided data analysis and the qualitative research practice, in general, is not our intention. The primary focus of our paper is on technical aspects of the presented CAQDAS tools; we review them based on the available functionalities and utility assets.

2. Examples of Free Programs and Their Basic Functionalities

The programs described below offer a broad range of possibilities offered by CAQDA. We intended to present several tools, which will not feature an identical set of functions, but they will show the whole spectrum of applications in this type of software. In this paper, we put great emphasis on not only the programs which enable us to work with a text but also those that allow us to analyze some audio-visual materials and create a visual representation of the analysis. We hope that thanks to this the quality researchers representing various schools and using different methodologies will find the tools that are right for them.

When selecting particular programs, we are also guided by the utility values related to the specificity of the working environment and their functionality. Therefore, all tools we describe are characterized by a logical structure, transparent architecture, and intuitive arrangement of individual options (Fielding, 2002). Therefore, virtually anyone who has some basic competence in the use of common applications such as text processors, should not encounter any greater difficulties in their case (Niedbalski, 2018).

Our article is of a reviewing and explanatory nature. It is based on observations made during our workshops and classes, as well as our personal experience as CAQDAS users. In the methodological layer, it combines the ethnographic and self-ethnographic dimensions.

The choice we made is the sum of our personal experience in the practical use of CAQDAS, which we have enriched ourselves with in the last few years. At the same time, we realize that these are highly individual issues and we, therefore, understand that opinions on the usefulness of this software can be different and expectations of individual users vary (Niedbalski, 2018; Niedbalski & Ślęzak, 2016). This is the reason we do not want to force anyone to use these programs (or CAQDA software at all). We just want to stress their capabilities and show some “technical” facilitation of analytical work involving their use. To better illustrate the possibilities offered by the presented software, at the same time arranging it under particular categories of their usefulness, we divided the programs due to the basic range of their application in a researcher’s work.

2.1 Programs for Working with a Text

Among an extremely large group of programs typically used for text analysis, we think it is worth noting such tools as OpenCode and WeftQDA. Both programs are extremely simple and intuitive, which makes them a friendly environment for the novice user. They enable various encoding, collating and comparing analytical categories, writing memos and in this respect, they are recommendable for potential users.

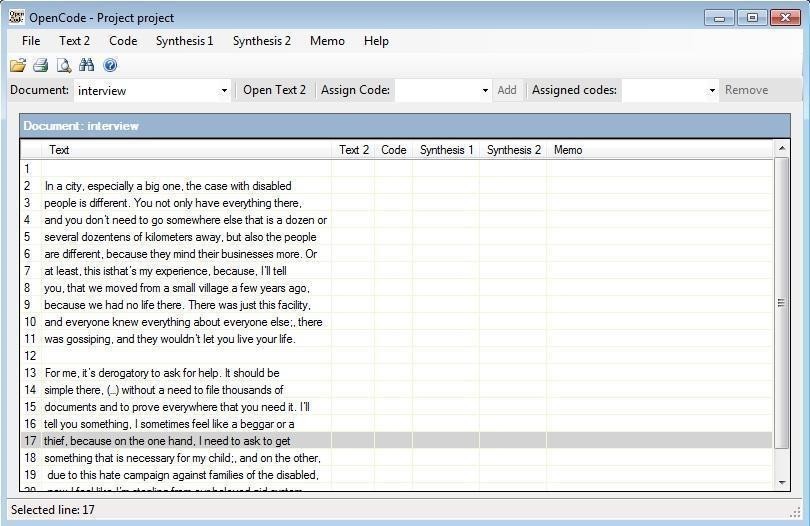

OpenCode is a tool for encoding qualitative data in a text form, such as interview transcriptions or observation notes. It was developed for the analysis conducted per the principles of the grounded theory methodology (Charmaz, 1994; Glaser, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Furthermore, it may be successfully used as a tool for classification and sorting any kind of text information, the analysis of which is conducted following qualitative methods.

Among the available functions of the program, the following should be pointed out: the possibility of creating a database of text materials; text searches for specific words; assigning codes to specific text segments; creating and managing categories for grouping generated codes; browsing and searching through the created codes and categories; creating memos for short information or analytical thoughts of the researcher; browsing freely selected elements of the project (codes, categories, memo) and their preparation for the printed version. The program has several limitations. First of all, the way of presenting (displaying) the data imposes a specific and unmodifiable layout of text materials, automatically dividing the content of the document into lines. Moreover, the imposed division of text can be quite artificial in certain cases, which is especially visible during data coding. OpenCode also does not give the possibility to adjust the access to particular functions according to the user’s needs. The possibility to import documents only in a .txt format seems to be a significant limitation of the program which makes it impossible to work on material previously formatted in another text editing program. Furthermore, OpenCode does not allow to edit a text that has been imported.

Similar to OpenCode, WeftQDA is software for analyzing text data such as transcriptions of interviews or field memos. The program offers a set of tools for work with text documents, intended for analyses carried out with qualitative methods with support from simple quantitative summaries. Among the reasons for choosing the WeftQDA program are completely free to access; ease and intuitiveness of use, which makes WeftQDA a program for practically every user; to use it, you only need the knowledge and skills at a level comparable to those required to use well-known office software; having the most important functions needed for analytical work, without unnecessary “overloading” with various options; in other words, the program has the features required to carry out a data analysis quickly and efficiently; the possibility to use the software in teams or a didactic process (Niedbalski, 2018).

It certainly is very useful for researchers who are willing to effectively organize their data and arrange new information arising from both the field and analytical work. Nevertheless, the WeftQDA program also has some limitations. First, it must be borne in mind that WeftQDA, similarly to OpenCode, only supports the .txt format, thus it is impossible to import documents without losing their formatting. It is also worth adding that every WeftQDA user should remember to make regular copies of the database because the program in its current version can be unstable, which can lead to the loss of the analyses conducted with it. Therefore, creating a backup (copy) version will protect us from possible software errors.

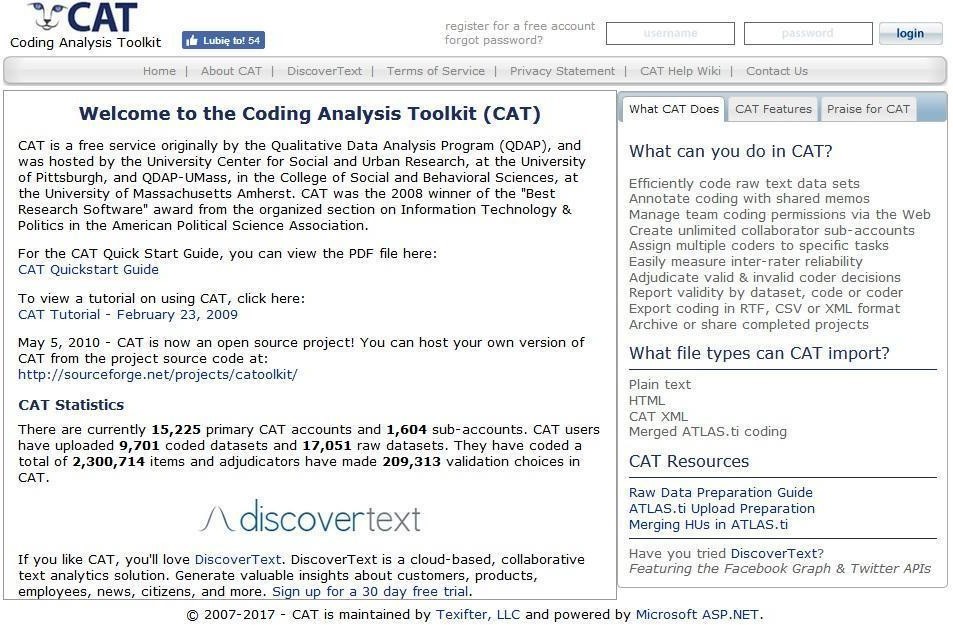

Two other programs we would like to draw attention to are CATMA and CAT. Similar to OpenCode and WeftQDQ, also these programs are intended for the analysis of text data. What makes them stand out is that they are both on-line tools and allow the opportunity to work as a single researcher or cooperate in real-time within a team. CATMA allows collating documents in a corpus and creating their collection. Importantly, the information contained in the program can be shared with other people (on a read-only or fully editable basis). For everyday use, it is also important that the data can be saved in the XML format and therefore easily exported to other applications. At the same time, all data uploaded to the server is protected, and the developers ensure they make every effort to ensure data privacy and IP protection. The following program’s features also deserve to be emphasized: almost every language of the text is supported, full integration of functions for description and analysis of data in a web browser, cooperation via the Internet enabling easy exchange of documents, annotations, and tags, freely definable or predefined tags, built-in visualization of search and analysis results, and analysis of complex text bodies.

The CAT (Coding Analysis Toolkit), on the other hand, enables efficient, transparent, reliable, and correct on-line cooperation on coding and text analysis. The program allows users to manage data, codes, and to analyze text materials. It also has an extensive reporting system allowing to generate information that comes from the conducted analytical work. The undoubted advantages of the program are its ease of use, intuitiveness, clear interface, and as a web-based system, it provides an opportunity to quickly and conveniently replicate and combine data, as well as to check the analyses performed by the team of researchers.

2.2 Tools for Working on Audio and Video Materials

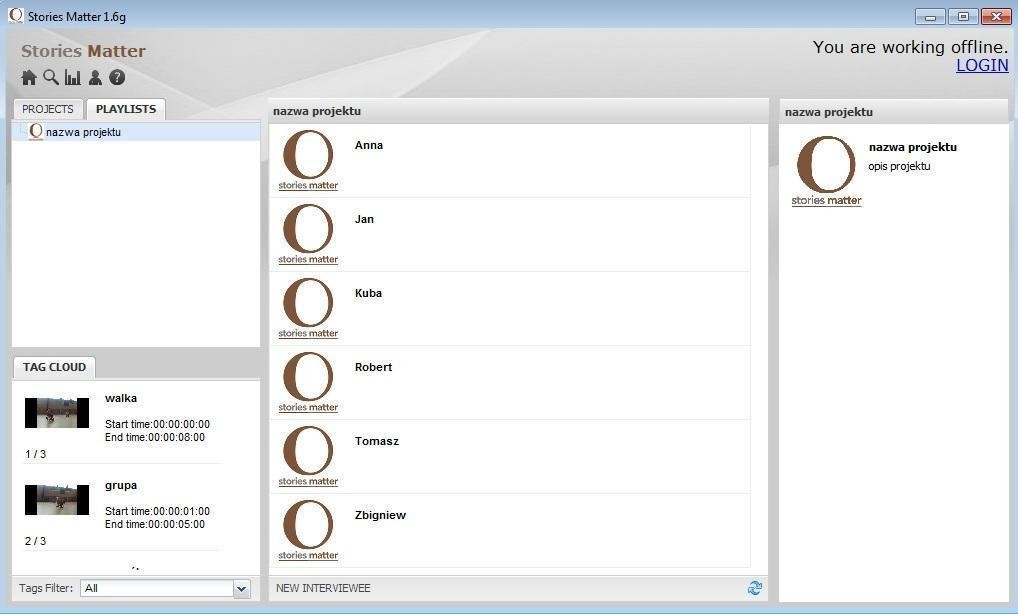

In their work, qualitative researchers often use visual data, which are both auxiliary (supporting) material for the analysis of text data, the main source of information and the basis for the conducted analyses. This is also supported by the emergence of modern CAQDAS tools, which, thanks to the development of technology, have gained the opportunity to include visual materials and all materials they support. STORIES MATTER, ELAN or TRANSCRIBER can be mentioned among the ever-growing range of such programs. STORIES MATTER is a tool designed for archiving digital video and audio material. According to the concept of its creators, it is supposed to be an alternative to transcription, and thus enable the collection, but also sorting and ordering of audiovisual materials. The program allows users to edit the recordings based on the user criteria, and to create summaries with audio and video files, arranged according to specific research themes or problems. Thanks to the system of notes and descriptions, Stories Matter allows to enter additional information about the collected files and their content, and the system of searching and creating a tag cloud significantly improves the process of recognizing key topics and issues raised by the interviewees. The users can also export the results of their work in several different formats, which facilitates their use in presentations or website design.

The unquestionable advantage of the program is its intuitiveness and simplicity of use, which allows almost everyone, even an untrained researcher, to quickly familiarize themselves with the possibilities of the software and apply it without the need for a long process of learning how to operate it. A disadvantage may be the limited range of file formats that can be imported into the program, as well as the need to describe them laboriously, especially when you want to enter all the data and information about each interviewee, or the specifics of the interview and its course.

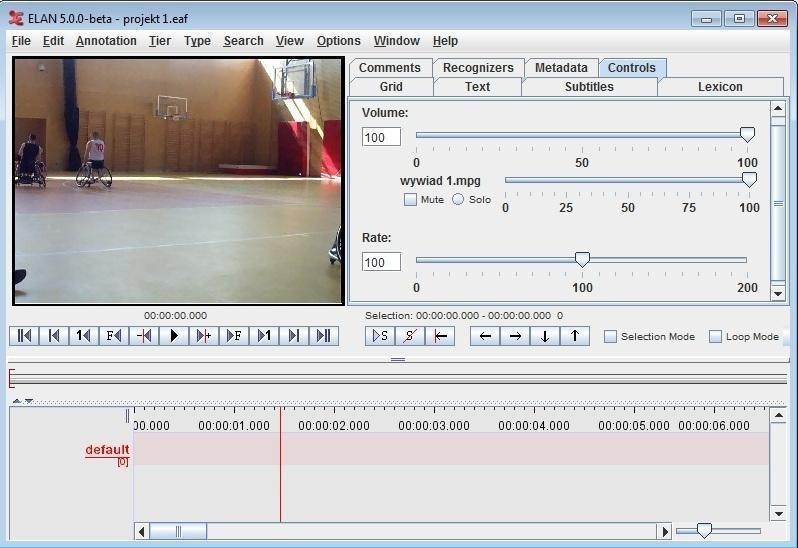

ELAN is also a program created for people who want to analyze visual data using computer tools. ELAN allows users to create, edit, visualize and search annotations for video and audio data. It is a tool specifically designed for language analysis including sign language and gestures, but it is universal and can be successfully used by anyone who works with video and/or audio data. An unquestionable advantage of the program is its clear interface and user-friendly layout. However, the program requires a certain amount of skill, especially when it comes to the correct understanding of the terms used in this tool. After just a few attempts, you can get used to its specifics and intuitively perform various actions.

TRANSCRIBER, is a tool for comprehensive analysis of statements. Transcriber is a very handy tool supporting transcribing data and organizing it, as well as for placing annotations as labels assigned to selected fragments of file soundtracks. It is equipped with many functions that will certainly support the work of a qualitative researcher. First of all, the possibility of dividing and segmenting the fragments of a soundtrack, transcribing audio and video materials, and a whole range of tags allowing to reflect precisely all the nuances of the interviews and specificity of the recording must be mentioned here. The unquestionable advantage of the program is the ability to read plenty of file formats and the support for a different length of recordings. An additional advantage of Transcriber is the relatively modern design and friendly, intuitive interface, so using the program should not be too difficult. All the displayed elements, i.e., folders or files, have an icon in front of their name, symbolizing the kind and type (e.g., a folder and a file, including among others audio, video file, etc.) which makes the work much easier and faster. A certain disadvantage in terms of the full functionality of Transcriber is the limited resources of built-in dictionaries, and therefore the inability to use the spell-check option. However, the Transcriber allows the introduction and process of data in the user’s native language, which is why despite several functional limitations it can be fully used for the processing and analysis carried out in a native language.

2.3 Programs for Developing Concept Maps

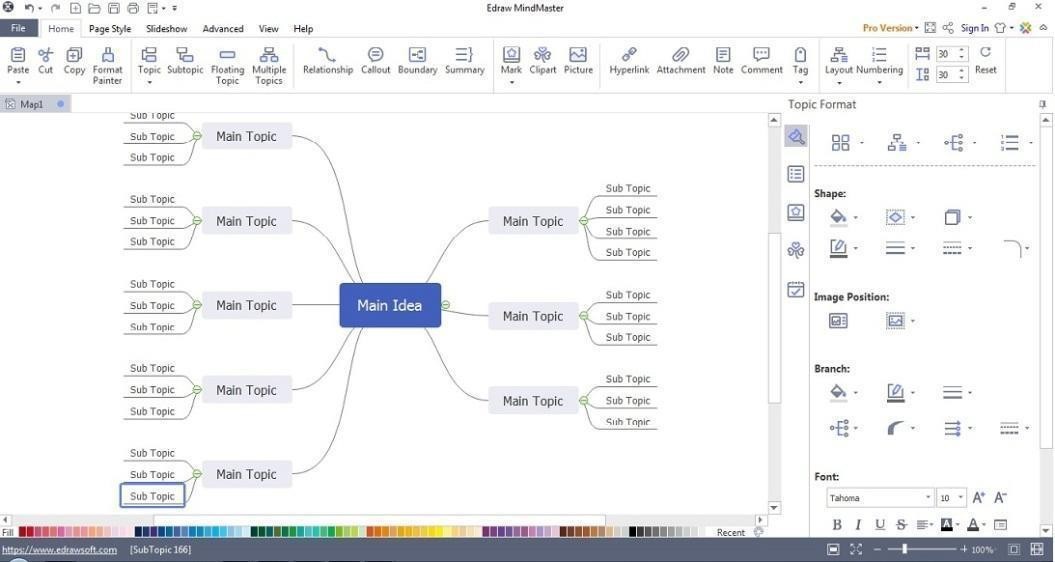

Currently, qualitative researchers often use visual representations of their analytical inquiries in a form of mind maps, integrative diagrams, or various schemes. The programs described so far did not allow to visualize the results of data interpretation or did so to a limited extent. Fortunately, a researcher who would like to use this kind of tool in their analysis can refer to programs from the CAQDAS family. We can use CMAPTOOLS or MINDMASTER as examples here.

CMAPTOOLS is an application for developing conceptual maps and presenting data in a graphic form. Therefore, it is a program for those who need to visualize their analytical concepts or just improve the data interpretation process. CmapTools allows for the creation of complex and advanced models that allow users to integrate and organize codes, and to graphically reconstruct the analyzed processes. CmapTools is a tool that has many useful features that allow users to edit, modify and, above all, customize the program to the needs of the researcher-user. Thanks to numerous editing features, it is possible to introduce various types of graphic files within the constructed models to complement and illustrate the presented concepts and visually enrich the concept map design. At the same time, the authors of the software aimed to create not only a tool, but also a support network, by consolidating the Cmap community and the possibilities of dissemination, sharing, and, above all, conducting discussions with other people using the program. This is how space is created for the exchange of thoughts, ideas, but also for consultation and suggestions that help to develop research and construct a model based on this research (Niedbalski, 2018).

MindMaster has several important advantages as a tool helpful in a qualitative researcher’s work. First, the program is designed to develop conceptual maps and interpret data with diagrams, arrange and integrate codes, and graphically reconstruct the analyzed processes. It will surely satisfy the expectations of even quite demanding users. Thanks to a wide range of options for transferring, exporting, and publishing data, the program can successfully support the work of an analyst, among others by using the support network of other researchers or simply by creating research teams. When you add a large number of options to edit and modify projects according to your preferences, you get a very functional and user-friendly tool for qualitative researchers.

MindMaster allows you to design a concept map consisting only of texts, but nothing stands in the way of enriching the project by placing even images or icons that will make it look much more attractive. It is worth adding that the program allows defining keyboard shortcuts. Using them will certainly speed up the creation of subsequent thought maps. Any concept map can be freely modified by adding or removing selected clouds, changing their content, size, or font color. Numerous graphic styles allow adjusting the look of a concept map to the user preferences. We will find here not only glamorous but also minimalistic templates. What is more, the designed thought map can be easily saved and sent to other people via email, for example.

A certain disadvantage of those programs is both CmapTools and MindMaster have a limited number of built-in options to support the researcher’s native language, which practically eliminates the possibility of using features such as a dictionary or spell check. It also seems that the number of options for visual modifications of the project may sometimes overwhelm the user, who will not always need e.g., several shades of a given background color or different line texture. Of course, this may be important for some people, so it is difficult to evaluate this multitude of editing options in a clear way. However, the above-mentioned remarks should not alienate the user, who can always create their support network and work on the project with a befriended group of researchers. To sum up, despite some limitations, CmapTools and MindMaster will certainly fulfill their tasks both as basic tools of the analyst’s work and complementing other types of software (e.g., OpenCode or WeftQDA described earlier), which do not have data visualization and integration diagram creation functions.

3. How to Choose the Right Software

This brief review of CAQDAS software shows well that there are plenty of different programs that belong to the CAQDA software family. In this situation, a question of which one to choose may arise (Prein et al., 1995). This concerns particularly those researchers who have no experience with this kind of software and would like to use its possibilities in the research design. Therefore, we think that anyone who would like to use CAQDA should first answer a few key questions, while we divided these questions into two “blocks”. The first, which we called the basic one, refers to the canonical issues of general computer literacy and evaluation of one’s methodological workshop, and it includes the following questions:

• Do I understand the specifics of the chosen analytical approach and can I apply the procedures of a specific methodology in practice?

• Do I know exactly what I want to do with my computer software?

• Do I have the appropriate competence and computer skills?

• Am I ready to devote sufficient time to learning how to use the software?

The second block of questions is about how to position the preferences for CAQDAS and how to choose the program. In this case, four main criteria/aspects must be considered.

• Project type - will the project be of an individual or group character? This is key information because team projects are much more complex and require very careful organizational planning. Therefore, it is necessary to choose such a program that will have a well-developed feature to allow several researchers to cooperate. Also, on this occasion it is also worth considering whether the project will be a one-off or whether we will continue this project in the future (or maybe it will be divided into stages with a longer time horizon).

• Materials adopted - will they be of one type (e.g., text) or different types (e.g., transcripts, documents, audio-video files, etc.)? If we want to use different data, we should choose those CAQDA programs that support such data and allow us to manage, sort (by type), or integrate (in different ways, considering analytical issues). It is also important to note the degree of structuring the data, i.e., whether it will be, for example, unstructured or narrative free interviews, or free interviews with the desired list of information or questionnaire interviews (provided that we use open questions in their structure).

• Characteristics of data analysis - are we going to conduct qualitative analyses or are we going to use a mixed-mode? Although software packages are called “qualitative analysis tools'', they can successfully carry out projects with mixed-mode methods. Since CAQDA programs are not used for statistical analysis of quantitative data, the data from e.g., answers to closed questions in the survey will have to be analyzed using software packages such as SPSS or Staistica. The quantitative and qualitative data can be integrated by importing quantitative data developed with statistical analysis software packages.

• Analytical approach (research method) - what specific method will we use? Nowadays, in the era of accelerating the development of CAQDA software packages, an increasing number of programs exist or are being improved, which are intended by their authors to serve the widest audience. This means that these programs must meet the specific expectations of different researchers coming from different theoretical schools and applying different research methods.

Only after going through the above “path” (checklists) of choice and answering the questions, can it be decided with much greater certainty, and above all, consciously, whether you want to use CAQDAS at all and which program to be able to effectively perform one’s research tasks.

4. What We Should Know Before We Become CAQDAS Users - Possibilities and Limitations of Software

Therefore, as our previous deliberations suggest, using computer software requires the knowledge of the specifics of a particular program, its functions, and the principles of its use. A researcher who wants to use these programs must engage some effort and time to learn about the possibilities of the software (Bringer et al., 2006), its architecture, but also (and perhaps most importantly) apply some changes in the perspective and often drop some worn-out habits of organizing a researcher’s workshop (Lofland et al., 2005). However, as has already been highlighted, using CAQDA causes the data analysis process to be more systematic and clearer. This somehow “forces” serious thinking about data and encourages the in-depth analysis. Furthermore, regarding the methodological paradigm, using CAQDA allows one to carry out a qualitative comparative analysis or research several hypotheses at once (Kelle, 2005). Among the advantages of software supporting the analysis of qualitative data, the possibility of mastering a considerable amount of materials is often cited, which can be easily processed, modified, sorted, and reorganized, as well as searched. This allows the researcher to have more control over the collected material. CAQDAS programs offer search options both within the text (or descriptions of audio-visual material) and within the created codes, memos, notes, and other products of the researcher’s activity.

The researcher also can group different elements of the project according to their preferences (Wiltshier, 2011). This gives a possibility of the comprehensive ordering of data, both the source material and any information that comes from the analysis carried out by the researcher (Seale, 2009). Hence, it is possible to make comparisons within the cases emerging in the research and to search for any differences and similarities among them. The architecture of CAQDA programs, in a way, forces the researcher to think constantly about the relationships between codes and categories, to compare and modify them. This allows avoiding the threat to qualitative researchers, which is associated with focusing only on data collection and omitting their in-depth analysis (Friese, 2019). CAQDA programs equip the researcher with the ability to write various types of memos and they smoothly intertwine data collection with analysis, thus moving from raw data towards theorizing at an increasingly higher analytical level. Also, CAQDA software gives a possibility for constant modification of all project elements as new data appear (Bringer et al., 2006). Undoubtedly, the use of CAQDA software has many advantages, and if it is used consciously, in a manner consistent with the principles of a specific research method, it may strengthen the researcher’s desire to achieve positive effects of his work (Macmillan, 2005; MacMillan, & Koenig, 2004). It should be remembered that CAQDA programs also have some limitations (Glaser, 2003; Paulus et al., 2018).

During our courses and workshops, we often drew our attention to the influence of the so- called “internal architecture” of the software exerted on the analytical process, i.e., the need to subordinate the analysis to the solutions implemented by the authors of a program (Friese, 2011). This means that the structure of the program can impose particular ways of sorting, searching, or analyzing the collected materials (Glaser, 2003; Holton, 2007; Seale, 2009). However, this is more a matter of how the researcher uses the possibilities of a given program and not the software architecture itself. Some authors (e.g., Glaser, 2003; Holton, 2007) take the view that using the software can cause various paths of data interpretation to be overlooked (because they structure analysis too much). Our personal experience shows that some users - especially in the early stages of learning a program - feel a little overwhelmed by the wide range of applications and possibilities offered by some, especially the extended programs. Often, a long list of features far exceeds the needs of an average user, and the number of options available can be challenging for some, especially inexperienced researchers. However, the existence of many options does not mean that the researcher must use them all. On the contrary, they should reasonably use the possibilities offered by the software and choose those functions which are consistent with their methodology (Bringer et al., 2004).

The above possibilities and limitations of CAQDA software are not exhaustive, however, they give a general view of the range of possibilities offered by such tools and doubts that their use brings (Jackson et al., 2018; Paulus et al., 2018). Above all, however, as we always try to draw the attention of both readers and participants of our workshops, it is crucial to be fully aware of the supporting nature of the software used. For we must remember that no program, even the most sophisticated and technologically advanced one, can relieve a researcher of their work (Bringer et al., 2004; Dohan & Sanchez- Jankowski, 1998). It is the reflectiveness, knowledge, and experience of the researcher that will determine the results of their actions (Lonkila, 1995). In other words, the only one responsible for the level of analysis and quality of the work performed is the researcher (Bringer et al., 2006). Therefore, this type of software should not be treated as a specific remedy for conceptual problems or data interpretation difficulties, and the expected results can only be achieved by combining the two basic roles of a conscious researcher-analyst and a skillful user of a program (Miles & Huberman, 2000).

We would like to draw the attention of beginner quality researchers to the fact that their hard and often lengthy analytical work can become not only more effective but also simply more enjoyable with CAQDAS. This does not mean, however, that it will be simpler in the literal sense since the improvement of the analysis process itself is de facto technical, not strictly factual. Therefore, not even the most advanced and complex computer program will take the burden of analytical and interpretation work off the researcher. This will not be provided by any tool, either for processing qualitative data or for working with quantitative materials. It should also be noted here that software packages dedicated to qualitative research and those dedicated to quantitative methods are by no means the same and should not be seen as similar. However, we would like to point out that the logic and design of the operation of SPSS or Statistica software on the one hand and CAQDAS software on the other is simply different. It all comes down to the specificity of the data and the methods used by the researcher. Hence, we should not compare them to each other and expect the same from them.

5. Summary

CAQDAS is currently represented by an unusually large group of programs that differ both in terms of the sophistication of functions and their purpose (Prein et al., 1995; Richards, 1999; Niedbalski & Ślęzak, 2016). Therefore, there are some significant differences in the CAQDA software family. In addition to tools as extensive as Atlas.ti, NVivo, MaxQDA, QDAMiner, and many others, which provide the researcher with the ability to encode data, create logical and contextual links between the generated categories, or verify the resulting hypotheses and then construct theories (Fielding, 2002; Kelle, 2005; Niedbalski, 2014; Niedbalski & Ślęzak, 2012), we have tools that are simpler in their construction, less technically advanced and usually poorer in the options implemented. However, this does not diminish their practical value and should not be a reason for a negative evaluation of such tools. Although free programs are usually not as extensive as the tools available for a fee, they are certainly sufficient for most beginner researchers, in particular, equipping them with the most important functions to assist in the process of qualitative data analysis. It is therefore a group of programs that has quite a wide range of applications, whereas this applies to a great extent to text data and is mostly limited to some basic but most important functions such as coding, sorting, and searching through data.

Nevertheless, as we have attempted to demonstrate in this paper, among free programs we can also find those that can be used to analyze visual data, including audio and video materials. There is no doubt that an interesting and noteworthy group is also free tools belonging to the CAQDAS family, which can be accessed via websites. With these programs, there is no need for a sometimes-troublesome installation process on one’s computer, no need to worry about hardware compatibility or its parameters, and at the same time, all data are archived and stored on external servers. Thanks to this, we gain additional background for our data, which is a kind of backup usually extremely valuable and carefully collected materials for us.

We emphasize that we intended to present programs that support the work of a qualitative researcher representing different schools and using various analytical methods. However, it must be remembered that each program is a kind of “environment” in which the researcher works and performs certain activities according to the so-called “software architecture”, i.e., the technical solutions used by its constructors (Saillard, 2011). However, developers of this type of software take care not to impose any methodological constraints. The matter of which of the programs we have discussed will ultimately find appreciation with the user is individual. Much depends on what the needs of a particular researcher are, and this depends on the methods they use on the issues they undertake and their personal preferences (Lonkila, 1995; Saillard, 2011).

In conclusion, we would like to stress that the programs we have described do not in any way exhaust the topic related to CAQDA software, but they can help to understand the variety of tools supporting the analysis of qualitative data and provide a kind of a guide to a rich list of such software. If we are not sure what exactly to choose, we should first think about what we really need, test the various programs and seriously consider which software functions we will use (Niedbalski, 2013; Niedbalski & Ślęzak, 2016).