1.A Tale of Technoculture: Netno’s Story

Technology pervades our societies, lifestyles, and experiences. It absorbs and releases cultural resources like a breathing being that inhales and exhales to survive. Technoculture designates the contemporary blend of technologies, social forms and cultural experiences that happen through and with technologies and that impact how we consume (Kozinets, 2019). As a result, the lives of human and non-human entities, what sociologist Scott Lash (2001) terms “technological forms of life” are flattening, stretching- out, speeding-up and lifting-out with and through technology.

More and more, our technological creations are reflecting us, connecting us, shaped like us, shaping us, replacing us, controlling us. They are increasingly impacting so many different aspects of our existence that they seem, qualitatively, to be a new force in our lives, our cultures, and our world (Kozinets, 2019, p. 620).

These various interplays between technology and culture generate experiences that scholars of cultural studies and science and technology have referred to as technocultural (Penley & Ross, 1991). Technocultural experiences embrace a broad range of domains - from information and communication technologies to economic policy, from politics to virtual popular culture, from sociality to consumption - and consequently mobilise a variety of discourses (Robins & Webster, 1999: 3). This variety of discourses incorporates knowledge, skills, competencies, and dispositions of individuals that are increasingly mediated through, and interdependent with, communication and information technology. Through their mediation of and interdependence with information technology, these discourses are embodied in the variety of cultural artifacts posted on social media platforms (Gambetti, 2021: 309). Cultural artifacts include “the various identities, practices, values, rituals, hierarchies, and other sources and structures of meanings that are influenced, created by, or expressed through technology consumption” (Kozinets, 2019: 621). Selfies, emojis, avatars, memes, GIFs, Zoom chats, augmented reality, Tik Tok challenges, Instagram stories, retweets, Pinterest dashboards, Facebook feeds, YouTube videos, Twitch streams offer vivid examples of a stretched-out, flattened, accelerated, and diversified compendium of contemporary sources of meaning.

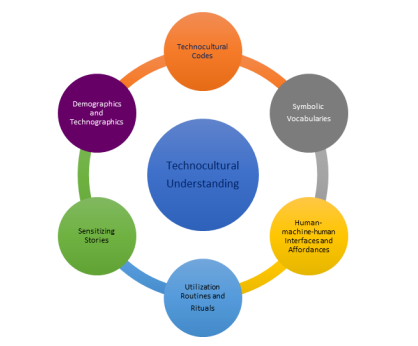

Against this background, netnography is a set of technocultural research practices (Kozinets, 2020). These practices constantly morph and alter over time and across domains, contexts, phenomena, countries, and researchers. They twist and turn, transforming to develop “technocultural understanding”, a type of cultural sensitivity that grasps and articulates the meanings of this vast variety of discourses generated within digital and through social media platforms. Netnography generates technocultural understanding through capturing different types of contextual elements that characterize the web of interactions, conversations and meaning creation and sharing that happen with and through technologies in digital and social media platforms. These elements - which are represented in Figure 1 - include:

The variety of discourses generated and popularized in digital and social media platforms evolves continuously along with the contextual elements that characterize their web of interactions. Similarly, etnography also evolves and adapts to adhere to a rapidly changing environment and to keep capturing deep insights. Over approximately two decades since its introduction during a Star Trek ethnography as a rich “field behind the screen” (Kozinets, 2001; 2002), netnography has been shaped into a “technological form of life” (Lash, 2001). That qualifies netnography as a research practice that stretches out, expands, opens up, flattens out, lifts out, speeds up, and slows down. Netnography of the Star Trek fandom was originally conducted by Kozinets as part of a 20-month intensive fieldwork at Star Trek fan clubs, conventions, and Internet groups, which was completed by 67 interviews with Star Trek fans (Kozinets, 2001). Ethnographic observation of the Star Trek Internet groups was used to get a deeper and technologically-situated understanding of how the cultural construction of consumption meanings and practices of the Star Trek fandom was shaped, altered, and even reinforced through online interactions (Ibid.). Since that first netnography, the method has expanded, opened up, and altered to always new levels.

Netnography today is stretching beyond what was previously possible. It is energized with purpose, electrified by access to new platforms, devices, and media. It shapes and is constantly being shaped by the various specific research contexts in which it is embedded. (Kozinets, 2021, p. 19-20).

Built around a strong and stable nucleus of guiding rules and codified practices, “when faced with the challenge of the new, it becomes free to adapt and evolve to the needs of divergent and dynamic contexts” (p.20). The latest adaptations and alterations of netnography illustrated in the book Netnography Unlimited (Kozinets & Gambetti, 2021) are vividly expressed as “an inner tension of netnography to self- perpetuate as netnography but also to be adaptively transformed by active researchers and their efforts across platforms, geographies, fields, industries, and times”. In this chapter, we build on this idea. We expand it by qualifying and illustrating the unlimited adaptive potential of netnography as something agentic. The notion of agentic netnography is inspired by post- humanist theories conceptualizing object ontologies (see, for instance, Knorr Cetina, 1997; Latour, 2005, Harman, 2018) and assemblage theories (see, for instance, De Landa, 2016; Canniford & Bajde, 2015; Epp & Price, 2010). These theories recognize non-human entities such as objects, machines, and the technologies constituting them, as having their own properties and capacities (e.g., cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral). In our technocultural playland, non-human beings exert autonomous agency and configure technosocial networks, assembling and disassembling heterogeneous material and immaterial resources into reality. Through promiscuous and desire-drenched intermingling, interactions grow inside and outside their networks. We conceptualize agentic netnography as an energized, electrified research force that incorporates both human and non-human shapes and sensitivities, senses and sensibilities. This type of research acts both to self-perpetuate and to establish increasingly meaningful and expanded connections with surrounding worlds. It becomes a type of virtually augmented research force that can move back and forth between the physical and digital worlds. As a method, it incorporates this intertwining hybridized physical-digital dualism in its own bodily and symbolic substance: Netno. Agentic netnography is thus the story of Netno. And Netno is the incarnation of agentic netnography. Netno is the way we can understand evolving research practices and their impact on the technocultural understanding of consumer worlds. Netno is also the imaginary narrator of this chapter. In the introduction to their essay plunging into the various embodiments of fabulatory art produced at the Burning Man Festival, Sherry and Kozinets (2021) build on Bergson and Deleuze’s idea of fabulation as “the making of fictions sufficiently vivid and intense to be capable of intervening in and shaping reality” (McLean, 2016, p. 47). This idea interprets anthropology and its evolutions such as netnography as a type of performance, a “fabulatory art” that becomes embodied in experimental or literary fashion. As a participant-performer within an artistic research formulation, a netnographer seeks to understand the objective social media and immersive technology world but to do so in a way invested with phenomenological understandings of that world. In so doing, she does not assume a detached posture that objectifies reality, but one that entails immersing and participating herself in the world’s own material substance (p. 105) and examining the roles of her own varied and sociotechnical subjectivities. Along these lines, we conceive of Netno as an expression of fabulatory art. Netno’s bodily and symbolic shape and substance are constructed for the sole (or soul) purpose of becoming immersed within and firmly anchored to the technocultural phenomena occurring in digital and social media platforms. Moreover, Netno is an agentic form of fabulation. He is capable of intervening and shaping the realities he investigates through his immersive, participatory and (eventually, along with the Greek trickster baby god, Hermes) interpretive acts of hermeneutic understanding. Figure 2 shows examples of evolving fabulations of Netno. This artwork by Robert V. Kozinets seeks to incarnate the different shades of netnography’s increasingly unruly technological forms of life. Netno has altered and adapted his forms over time to survive, to become more impactful and more fine-tuned with the evolving technoculture that he swims within and surrounds himself with. As incarnation of netnography, Netno is what we term a “human-fluid” entity. He is part being and part non-life. As such, he blends human, animal, mythological, and machinic sensitivities to capture the deep, nuanced manifestations of the spiritual, technical, cultural, and social lives of people, animals, objects, and brands. He also encompasses the liminal existences of post-human entities such as AI- and CGI-humanoids and robots. Netno’s big, attentive, surveillant eye scrutinizes the consumption forms generated in the techno social scapes of digital platforms. Netno’s ears are sharp radar detectors that follow every whisper in the cluttered clucking chattering of the world wide web crowd. Netno’s big, hungry mouth is an abyss of desire, starved for digital input and delectable foodporn, constantly eager to taste, swallow and digest consumers’ cultural labor performed in social media (Carah, 2014). Plastic Man is a fictional comic book character who can stretch his body and limbs into any imaginable shape, such as becoming a tree, a car, or a bouncing ball. Like Plastic Man, Netno’s long limbs can become movable bridges that connect to, embrace, and sympathize with the investigated forms of life, reaching out like Plastic Man’s infinitely extensible limbs to embrace the entire world. Yet Netno’s raptor-like feet are stable, hooked into the ground to firmly grasp the peculiarities of each digital sub-cultural context and to absorb its strength and to stand, swaying, against the flowing tides of its energetic vibes.

In this chapter, Netno guides us through a multi-sensory journey into various examples of meaningful worlds of netnographic discoveries where agentic netnography captures evolving technocultural phenomena which blend consumers with brands, media with technologies, and socialities with culture. These include: human and post-human social media influencers, Instagram foodporn, Facebook social assemblages of post-truth consumption, youth culture infiltration and hijack of tobacco social media branding, and the syncretic flows of technocultural Chinese beauty scapes. For each of these agentic netnographies, Netno will guide us to understand various aspects such as the context, the goals, the key methodological specificities, and the most relevant insights generated in each netnographic experience. This journey is a story written by Netno’s pen, seen through his single unblinking eye, tasted through his hungry, bottomless mouth, touched through his gentle limbs, and heard through his sensitive ears. The journey starts with a dive into the set of specific research practices that characterize agentic netnography, with a particular focus on the three data collection stages: investigation, interaction, and immersion. These three stages represent the heart of netnography. In the next section, Netno will then walk us through these practices with his firmly grounded feet.

2.The Research Practices of Netnography in Marketing and Consumer Research

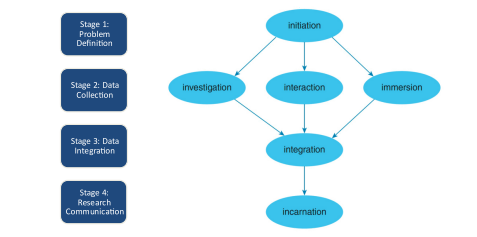

Beyond being a rigorous research method including a set of specific research practices, netnography is also a living body of knowledge. It is an open repository of sensitivities that allows us to explore, fine-tune with and make sense of technoculture. Over the quarter-century, since Robert Kozinets first founded the technique, netnography has established itself as the most popular scientific approach of applied qualitative research focusing on social media in the marketing and consumer research areas. This is witnessed by the significant number of academic studies in the marketing and consumer research domains that have applied netnography to perform a deep, qualitative investigation of the digital consumers’ worlds in the past two decades (Bartl et al., 2016; Tavakoli and Vijesinghe, 2019). A recent volume by Kozinets and Gambetti (2021) examines how numerous academics and industry researchers have developed and applied netnography to many theoretical and practical questions. Netnography follows a set of standards and steps, combining several research methods to create a cultural awareness of customers' lives as well as profound insights into the hidden worlds of consumer meaning and desire. Netnography is a collection of six unique, but intricately related research activities carried out over the course of a four-stage procedure (Kozinets, 2020: 139-143). As seen in figure 3, the first stage is concerned with problem definition, which is where the research project's investigatory direction must be determined. The researcher considers a variety of themes, methodologies, and theoretical lenses during this phase, and then creates and refines the research questions that will guide the netnographic study design. Data collection is the focus of the second stage. The investigation, interaction, and immersion are the three research operations covered in the data collection phase. In performing investigation, the researcher utilizes search engines and other automated means to seek and find traces that are relevant to the research questions previously identified. Using a combination of various keywords in search engines the researcher identifies and sorts out relevant sites, as well as individual conversations, topics and sub-topics, tags such as hashtags, and visual images or other non-textual representations. The investigation allows the researcher to localize, examine, and interpret these traces to scope out meaningful data that can provide appropriate clues to include in the netnographic field sites. This phase allows the researcher to develop a wide, “telescopic glance” that maps out the contours of the investigated phenomenon. During the investigative phase, a very large amount of potentially significant data is identified and scanned. Using the “data condensation” processes described by Miles et al. (2014), this large corpus of data is then gradually selected, simplified, abstracted, and transformed by searches and choices to focus only on those theoretically relevant social media traces, as Kozinets (2019: 71) did to scope out the contours of capitalism, religion, consumption, and utopia discourses in YouTube.

The interaction entails the researchers’ direct engagement with research participants. Although the interaction is already performed both in the investigation phase while scouting, searching, exploring, selecting, scraping, and downloading portions of online field sites, and in the immersion phase while engaging with data through unobtrusively taking personal notes, some projects require a more deliberate form of contact. The Interaction may be performed typically through online participant observation and/or through interviewing, but it may also include the creation of a netnographic interaction research webpage (e.g., a Facebook group or Instagram profile, or YouTube channel purposively created for the research project) or the use of digital diaries and mobile ethnography techniques. The Interaction can be a planned or an emergent phase of the netnographic design. It pops up as a need to get a deeper, “microscopic glance” at a phenomenon for which, for instance, no sufficient online clues are found to develop an adequate level of cultural understanding. Or it could be that online participants are reluctant to reveal certain meanings in public social media conversations. It could also be that online interactions are unclear and incomplete and require deeper explication. The immersion draws from the anthropological metaphor of a human being living embedded in a specific culture just as a fish lives in water. In netnography, immersion infers the researcher’s inhabiting of a specific bounded technocultural context where the investigated phenomenon unfolds. The immersion then represents a metaphor of the researcher diving deeply into the cultural context behind individuals’ conversations, interactions, postings, and experiences to grasp their meaning as a culture member might. Immersion represents the heart of the data collection phase and is focused on identifying highly meaningful “deep data”. Deep data refers to any element of collected traces that is particularly revelatory, rich in meaning, and relevant to the research questions. Immersion is about seeking, finding, and recognizing deep data and understanding how consumers create and share online their own story worlds. Those worlds are very rich, thick in a Geertzian sense. They include identities, symbols, values, languages, rituals, desires, needs, experiences, encounters, conversations, and discoveries that shape language, lifestyle, and sensitivities. Immersion triggers a personal, intellectual, and emotional involvement of the researcher that can play out as asynchronous or as an asynchronous reflective effort. Immersion in netnography is more than an experience but becomes the experience of the researcher. That capturing takes the form of an immersion journal. The immersion journal allows the researcher to map out the research territory, recording overviews and details of her encounter with data, integrating her insights coming from the empirical dataset with extant constructs and abstractions, and capturing her own experiences with introspective reflection (Kozinets, 2020, p. 284). The immersion journal will include the personal, reflective, and emotional notes of the researcher. Through the journal, collected data are elaborated on and examined to capture meaning in the form of revelations, epiphanies, black swans, exceptions, emergent typologies, and recursive patterns that can contribute to crafting an overall sense- -making of the investigated phenomenon. These notes can be composed of various types of data, such as textual, graphic, photographic, and audiovisual. Along with transcriptions, archival sources, hypertextual links, and screenshotted images, they are assembled to form a “carefully cultivated curation” (Kozinets, 2020: 397). Immersive notes blend the revelatory depth of specific observed clues and details with the width of emergent patterns of individual and collective practices. Together, these elements generate a virtuous interplay between the “telescopic view” and the “microscopic glance”. This big and deep focus on data allows the researcher to develop a virtuous cycle of understanding and abstraction. The third stage is devoted to “data integration”. The integration operation refers to the combination of analytical and interpretive activities, whereby the researcher develops the hermeneutic understanding necessary to abstract and theorize from the observation of the field. Integration is an iterative process. In it, the researcher seeks to answer by moving back and forth between data sites, online traces, deep data, immersive notes, and more abstract levels of emergent theoretical construction inductively developed from the field and compared and contrasted with previous literature. Integration is, therefore, an ongoing process of decoding, translating, cross-translating, and code-switching between parts and wholes, between data fragments and holistic conceptualizations. As the researcher connects the insights of the findings to the research questions, integration includes efforts related to analysis (breaking down into parts), interpretation (building and connecting wholes), and combination (co-constitutive encounter and collision of perspectives that generates new meanings and knowledge). In the integration phase, the researcher collates data, codes it, categorizes it, and applies methods of interpretation such as humanistic, phenomenological, existential, discourse, or hermeneutic methods to generate cultural understanding that responds to the research question(s) or topics of inquiry.

The fourth and final stage of netnography is focused on “research communication”. This stage entails an operation of incarnation. Incarnation depicts an act of embodiment of something abstract into a concrete, tangible, and accessible form. What originated as an idea for exploring a phenomenon, as knowledge goals and research questions, has been subsequently embodied in a research design of interrelated phases and operations of data collection, analysis, interpretation, and integration. When the research process is concluded, the researcher must craft a narrative. That narrative incarnates the research in a form of tangible content that can be accessed by others. Incarnation can assume many shapes: a poster session or a competitive paper to be presented at a conference, a research manuscript for peer review in academic journals, a book chapter, a visual art manifestation and fabulation such as a painting, a sculpture, videography, a poem, or any other technological form of life that is deemed appropriate to convey the meanings of the research. The videography of the Burning Man’s deep ethnographic exploration produced by Kozinets (2002) offers a vivid example of how rigorous research can be incarnated in a revelatory audiovisual artwork that evokes infinite suggestions and emotions through which each spectator can encounter her own Burning Man spectacle. In the following sections, Netno navigates us through various netnographic explorations and discoveries that reveal the meaning of agentic netnography. Through each exploration, the adoption of particular specificities in the research repertoire uncovers new meanings, typologies, and patterns of technoculture. For each netnographic exploration Netno will provide context that helps us understand the types of cultural phenomena that are most appropriately investigated through netnography. Then, he will disclose and zoom in on specific netnographic practices along each of the data collection, analysis, and interpretation operations (i.e., investigation, interaction, immersion, and integration) that reveal the types of insights that can be reached using a thorough and localized application of the method.

3.Agentic Netnography in Practice: A Journey into Netnographic Explorations

3.1 Investigation: Mapping Out the Contours of Virtual Influencers

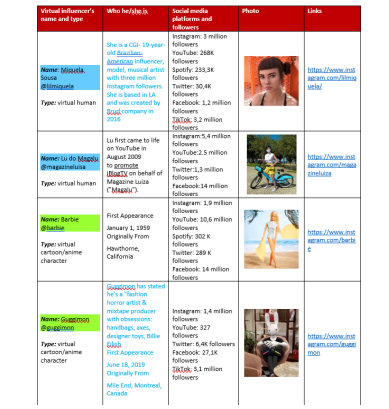

Virtual influencers, also called Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI) influencers, are computer-animated fictional characters who are programmed to resemble and behave on social media like human influencers. To marketing scholars and practitioners, virtual influencers may represent a fascinating phenomena at the intersection of social media, AI, and influencer science. In particular, virtual influencers are experiencing exponential growth in popularity as they show an unprecedented capacity to develop cultural proximity to their human followers. This closeness leverages attractive identities and the latest consumer trends. Virtual influencers have recently become trending topics in social media conversations and expanding their followers’ reach and engagement, especially among Gen Z and Millennials (Hype Auditor, 2021). Moreover, virtual influencers are experimenting with novel marketing avenues of monetization that are breaking the existing boundaries of conventional branding. As virtual influencers represent a new, dynamic, slippery, and still a largely unknown technocultural territory, a netnographic study proves to be the most appropriate method to achieve an in-depth cultural understanding of virtual influencers as a marketing and consumer culture phenomenon. In their netnography, the authors of this chapter have mapped out the contours of virtual influencers as new social media brands and content creators by investigating their self-presentation practices and their follower engagement strategies. In such a rapidly evolving, quickly growing, and unexplored territory, defining the scope of the investigative operations was particularly crucial. This required a very scrupulous exploration and assessment of online sources to be able to scout, identify, select, and scope out the relevant virtual influencer characters to include in the research. This investigative phase required us to identify and map 174 virtual influencer characters around the globe. These characters included objects, cartoons, manga, animals, and hyper-humanized computer-generated characters. All of them produce and spread content across a range of social media platforms in different languages, across different countries, and with different influencer tiers and follower bases. Figure 4 shows a screenshot of the overall dataset generated in the first scouting and identification phase of the investigative operations. Figure 5 zooms in on a detail of the classificatory table produced during this investigative phase.

Figure 4 An overview of the investigative dataset composed in the scouting phase of virtual influencers.

3.2 Interaction: Co-Constructing Foodporn to Energize Networks of Desire

Foodporn is a term originally used to designate an unattainable and often extreme photographic food portrayal. In their ethnographic and netnographic study of the consumption world of online food image sharing - a broad field that includes everything from friend networks to food bloggers - Kozinets et al. (2017) adopted and extended Deleuze and Guattari’s desire theory to conceptualize desire as something which connected human beings and technologies, yet something independent of them, something powerfully connective, built into technosocial systemic, and which spurred both polarization and innovation. Contrary to a large body of work that predicted that technologies rationalize and disembody consumer desire, the authors revealed the emancipatory possibilities of the unfettered desire that flows through bodies and with connective social technologies. They conducted a longitudinal ethnographic and netnographic investigation that led them to theorize about networks of desire as a passionate new universe of technologically enhanced desire to consume. This new realm is produced, expressed, circulated, magnified, and energized on digital platforms. In their netnography, the authors performed an intensive data interaction. It was an immersion that reflected upon a lifetime of experience and over a decade of structured food netnography. Research engagement was based on field research conducted online and in person over 16 years and encompassed participation in and observational lurking on food sites since 1998. As well, three more recent years of additional intensive fieldwork ensued, encompassing food creating, eating in restaurants, photographing foodporn, posting it, and interacting around it. This gave the researchers a rich appreciation of the overall foodporn phenomenon. Netnographic data collection spanned blogs, forums, and social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, Instagram, YouTube, Pinterest, Vine, and Platter. Moreover, the authors engaged in an active newsgroup posting, in the production of a food blog, and in the creation of an ad hoc Facebook group dedicated to foodporn, which gathered self-selected, convenience sampled participants who shared their stories with the researchers in a free and open manner. Of course, there was also a free flow of their food image sharing experiences, emotions, and stories (which, amazingly, continues on Facebook to this day). This intensive level of researcher engagement and interaction gave the investigation cultural depth.

3.3 Immersion: Immersive Journaling to Identify Patterns of Post-Truth Consumption

Post-fact society refers to a society in which citizens are less frequently exposed to similar sets of facts that may allow for a shared perception of objective truth (Mihailidis & Viotty, 2017, p. 447). In the context of social media, consumers’ interactions shape the ongoing formation and dissolution of ephemeral social assemblages around topics where post-truths and post-facts are socially constructed as the result of an ongoing negotiation process. To develop a cultural and situated understanding of the discursive patterns of post-truth formation and consumption in social media bounded interactions, Kozinets et al. (2018; 2021) conducted a netnographic study. They set their study in the dog breeding, dog healthcare, and dog food and nutritional contexts, purposively scoping out a blend of Facebook’s field sites where multiple beliefs and truths are generated as a result of an ongoing interplay between traditional science, pop-science reflecting a neoliberal and self-empowered consumer, and emotional engagement. These Facebook sites produced a rich and variegated flow of controversial narratives and counternarratives that resonate with technologically-enhanced collective power dynamics and cultural tensions. To capture the recursive discursive patterns whereby post-truths are formed and consumed in Facebook’s conversational flows, each of the three authors performed a deep, longitudinal, 5-year immersion in the field sites. This collective effort generated immersion journals including personal, emotional, and reflective notes. The notes blended insights with different types of online traces such as texts, photos, memes, videos, emojis, GIFs, and postcards. These journals, which also included transcriptions, archival sources, hypertextual links, and screenshotted images, crafted a digitally cultivated curation of more than 80.000 words. This digital curation was expressed in different textual formats such as PowerPoint slides, MS Word files, Excel spreadsheets, Canva pictorial collages, and audio- and audiovisual diaries. Figure 6 shows a modular composition of selected reflective notes creatively expressed both as text and as visuals, along with screenshotted portions of Facebook conversations included in the authors’ immersion journals. This composition was produced by the authors in their effort to bring to light and visually express in an evocative way one of the recursive discursive patterns of post-truth formation.

3.4 Immersion: Revealing Youth Culture Infiltration of Tobacco Social Media Branding through Deep Data

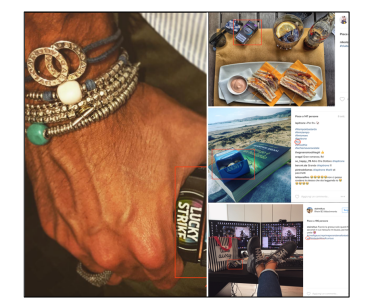

The regulatory environments around tobacco marketing and sales are restrictive but constantly shifting. And the industry is constantly shifting too. It invents new products, and it engaged in media substitution and reinvestment in promotional spending. The unintended side effect of all this churn is that tobacco marketers are constantly innovating. They build products and marketing to circumvent and/or undermine regulatory interventions, navigating the empty spaces left void by these evolving regulations. These qualities make tobacco marketers a fascinating site for the study of the intersection of contemporary consumer culture, new media formations that hybridize digital and physical contexts, new power dynamics bonding together social media influencers and their followers, and marketing techniques and technologies. In this dynamic and slippery context, Kozinets et al. (2019) set a multi-site, multi-researcher, multi-language ten-country netnography that was commissioned by Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (CTFK), the leading advocacy organization working to reduce tobacco use in the United States and around the world. Social media data collection expanded into a range of other techniques. These included participant-observation of branded events, online and face-to-face interviews, document analysis, and exploration of major industry players and facilitators. The netnography managed to blend investigation, interaction, and immersion research operations with an unprecedented level of depth and width. The scope of this research was quasi-investigative, as the main goal was to shed light on the complex influence dynamics whereby the big four global tobacco companies (i.e., Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, Imperial Brands, and Japan Tobacco International) surreptitiously targeted young consumers around the globe to promote smoking as desirable. This netnography entailed intensive immersive fieldwork combined with iterative reflective work performed over a 6-month period. Field immersion required a high level of cultural sensitivity to capture weak or hidden signs of brand cultural infiltration. Moreover, it required a total, naturalistic embeddedness in the cultural world of youth and their independent and free-spirited lifestyle as credible “insiders”. Finally, it required a very careful and respectful posture which we term “empathetic professionalism”, through which researchers approached their informants, got immersed in relevant consumption experiences with them, gathered their deep stories, and were able to share them appropriately, with maximum respect for anonymity and ethical concerns. This netnography’s deep data revealed a hidden market ecosystem organized around a complex and interlinked series of consumer-activating events, training sessions, sponsorships, branding moves, and consumer recruitments performed by online and offline paid and unpaid brands ambassadors and social media micro-influencers. Through this complex market ecosystem, youth culture, activist discourse and practice were subverted and transformed to benefit tobacco brands in a way that circumvented the regulations. Figure 7 shows a curated combination of deep data. The data reveal a plethora of seemingly organic posting through which micro-influencers openly promoted Lucky Strike cigarettes. Acting as lifestyle facilitators, these influencers popularized tobacco. Their evocative tobacco-resonant hashtags, which suggested like-mindedness (i.e., #likeus, #lus), encouraged positive associations between smoking and independent and desirable lifestyles.

3.5 Integration: Methodological Bricolage to Achieve Localized Hermeneutic Understanding of Chinese Beautyscapes

The first example of data integration comes from a netnography that Kozinets, Gambetti, and Gretzel conducted for an Italian business client - ArtCosmetics, operating globally as a business-to-business contract manufacturer specialized in color cosmetics. ArtCosmetics sought to explore Chinese cosmetics consumers’ changing notions of female beauty and how such perceptions become translated into cosmetics tastes and routines. As the company’s competitive advantage heavily relies on anticipating consumer insights and delivering product innovation, this netnographic research was meant to inform the new product development efforts of ArtCosmetics. Data integration combined depth interviews of Chinese consumers, Chinese social media immersion, and the inclusion of immigrant Asian/Chinese-American influencers and immigrant Chinese consumers in the netnography research process. It revealed a rapidly shifting concept of beauty (Gambetti et al., 2021). The changing notion of beauty resonates with traditional Chinese cultural, ethnic, and spiritual norms but also selectively includes novel facets. Netnography uncovered an ongoing negotiation at work between Chinese cultural stability and fluid globalization that plays itself out as a tension between beauty meanings, linguistic conventions, and imagery deriving from East and West. The transition from various emic elements to an etic dimension of Chinese beauty enabled the researchers to disclose an emergent syncretic combination of Eastern and Western beauty tastes and influences, which was reflected in a half- breed notion of beauty and numerous related cosmetics regimes (including many of which used the racially charged term “half-breed”). Throughout the research process, the researchers performed data integration between different research techniques (interviews, observations, immersive journaling) in an effort to balance more generalized abstract-level hermeneutic interpretation with specific localized understandings and their needs for adaptations and methodological bricolage. These peculiarities were reflected in the necessity for agentic netnography to perform multilayered alterations. These included things such as: navigating limitless varieties of relevant Chinese meanings, images, and symbols; carving out the ability to understand and adapt to the algorithms ruling Chinese and American social media platforms; incorporating body language and expression of interviewed women; capturing the meanings of multiple geographical locations; and getting familiar with Chinese and global cosmetics and skincare brands and products, skin types and colors, and many other meanings (Gambetti et al., 2021, p. 210). Figure 8 zooms into a multilayered cultural meaning that emerged from these Chinese investigated beautyscapes. The beautyscapes are incarnated in language, body, self- and beauty-concept, time, and age perception, and ultimately skincare tastes and regimes. This emerging multilayered cultural meaning was the fear and the concern felt by young Chinese women of “getting old at a young age” (i.e., the notion of “kang-chu-lao” in the Chinese language). This cultural facet incorporates a plethora of meanings, images, symbols, language elements, and specific rituals of skincare routines performed by Chinese women already at a very young age - as you can see in a snapshot of Figure 8 - that are revelatory of novel ways of self-care and beautification. These novel formations open up new avenues of product development and new targeting opportunities for cosmetics brands.

4.Limitations and Final Considerations

All research methods have limitations, and, for many, their limitations can be their strength. Netnography is limited by its reliance upon skilled human interpreters, who are relatively few in number. It is limited in its willingness to precisely quantify matters because it seeks understanding and a knowledge of context instead. Depending upon its budget and techniques, a netnography might seek to understand vast amounts of social media data-but those techniques are better left to big data analysts. Netnography’s strength is in the particular, the specific, the nuanced, and the real. It forsakes abstraction for description and computation for consideration. Despite these limits, an interesting preliminary exploration of the possible interplays between human- and AI machine-conducted netnography that might allow combining small and big data has been carried out in the form of an experiment by a group of professional German netnographers working for Hyve research and consultancy company (Marchuk et al., 2020. This experiment confirmed the necessity for human researchers to handle crucial moments of data analysis and hermeneutic interpretation to develop sensitive and meaningful cultural insights that AI machines are not capable to mimic. In particular, the study revealed that machine-driven netnographic research tends to outperform human labor in data collection, data clustering, and partially data analysis, especially with big data samples. Human-driven netnographic research, instead, proves to be way more effective in identifying unique content, highlighting weak or rare signals for uncommon needs, performing empathetic data analysis, and above all generating insights and engaging in storytelling (p. 199). In sum, human sensitivity, creativity, and talent show a superior capacity to integrate, interpret, and communicate the research insights, perform abstractions, and relate insights to past conceptualizations to generate new knowledge, advance theory, and inspire innovation. These latter capacities cannot be reproduced by machines yet. We hope and trust this chapter has presented you with something of a wild ride. Like the host of a dark ride in a theme park, our trust cyclopean mascot, Netno, has introduced you to a multidimensional new realm of social media investigation. Interspersed in the darkness have been moments of pristine clarity. We have clearly explained what netnography is, what it does, what it seeks, and how to enact it.

Qualitative researchers who are interested in more conventional and pedagogical accounts are invited to continue their exploration in a range of recent publications such as Kozinets (2020) and Kozinets and Gambetti (2021). The latter text may be particularly relevant to researchers seeking to explore how a variety of researchers have applied the fundamental methodological ideas of Kozinets to a variety of different research questions and contexts. Our purpose with this chapter was somewhat different: to elaborate as well as to entertain. We want to entice you with the energy and enthusiasm of a new generation of qualitative researchers who are putting on the Infinity Gauntlet of agentic netnography, snapping their fingers, and hoping to create disruptive blips in antiquated modes of research and thinking. What you've encountered in this chapter includes a range of different performance stages, each of which has presented you with original formulations intended to delight and create imaginary points of departure upon which your own research can, perhaps, one day take flight. Will you explore the energies of desire, and the technosocial networks they build around them, within a new technocultural phenomenon of your own choice? Will you chase down the latest happenings in social media space-the augmented virtual influencers of your own future day and age? Will you try to solve the growing rifts, divisions, polarizations, and extremes of social and political life currently spreading like viruses of hate and fear across the globe? Will you take on corrupt industries and inefficient, outmoded regulatory regimes, exposing the detrimental public effect of these insidious circumstances? Will you seek truth in a post-truth world, crystallizing your insights into research revelations? Perhaps, for now, only Netno knows the answers.