1.Introduction

In qualitative research, drawing on a blank sheet of paper during the interview is one of the tools in the researcher’s toolbox (Banks, 2001; Gwyther & Possamai-Inesedy, 2009; Leavy, 2017). This technique is increasingly used in social sciences because of its many advantages; it allows the respondent greater freedom of expression (Cohenmiller, 2018), encourages the respondent to speak (Catoir-Brisson, Jankeviciute, 2014), to address sensitive topics (Katz & Hamama, 2013; Knowles & Cole, 2008; Woolford et al., 2013) and can reduce the respondent's stress during the interview (Sandmire et al., 2012). Furthermore, the visual expression of the drawing reveals “formerly dormant elements” (Guenette & Marshall, 2009, p. 87) such as spatial dimensions (Girard et al., 2015) which would not have been addressed with verbal expression alone. Ultimately, the combined use of drawings and interviews would allow for the collection of complex qualitative data regarding the respondent's experience. Qualitative research on the experiences of the chronically ill makes little use of the drawing technique and mainly relies on interviews - biographical or semi-directive - and participant observation. Both sociology and health psychology have incorporated the question of social support for the chronically ill (Bury, 1982; Carricaburu & Ménoret, 2004; Martire & Franks, 2014; McCaughan et al., 2018; Vega, 2012), but these studies “tend not to care what this support actually entails” (Defossez, 2021, p. 6). On the other hand, sociology of networks provide precise data on the social support of the chronically ill (Akerman et al., 2018; Bidart et al., 2011; Bustamante et al., 2018; Fernández-Peña et al., 2020), but these quantitative studies give little insight into the personal experiences of the respondents. As part of a qualitative research study on the support networks of chronically ill people during the COVID-19 health crisis in France (PARCOURS-COVID Project), we decided to combine semi-structured interviews and drawings. The period of lockdown (March-May 2020) had a considerable impact on the chronically ill who were identified as a population particularly at risk of contamination (Lefève & Ricadat, 2022). Strictly confined, they relied on members of their support network to provide them emotional, instrumental and informational support (Thoits, 1995). The research study aimed to analyze the lockdown effects on the reconfiguration of the chronically ill’s support networks while remaining as close as possible to the subjective experience of the individuals.This methodological approach led us to a reflexive analysis of our research process. The research questions guiding this study were: How does drawing contribute to the understanding of the support received by the chronically ill? Beyond this case study, how is drawing combined with interviews useful for qualitative research? What are the biases of this method and how can they be avoided? Based on our research experience with chronically ill patients, this paper aims to offer some feedback on the advantages and limitations of the combined use of interviews and drawings for qualitative research.

2. Methods: interviews and drawings

Our study aimed to document chronically ill patients’ cure and care experience during the Covid-19 pandemic (Ricadat et al., 2021). One of its objectives was to identify their support networks during the health crisis, and particularly during the first lockdown between March and May 2020 in France. Three sources of data were collected and analysed:

2.1 Oral account of chronically ill patients’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic

From January to July 2021, 54 in-depth interviews with patients suffering from chronic conditions (cystic fibrosis, kidney disease, hemophilia or mental health conditions) were conducted. All patients were contacted via healthcare professionals or patients' organizations met by members of the research team during the previous exploratory phase. They were all informed beforehand by an information letter about the purpose of the study and how it would be conducted. Each volunteer was then e-mailed by the one or two researchers from the team who were to conduct the interview. Most of the interviews were conducted by videoconference (on Zoom® software), except with respondents with mental health conditions who were systematically met in the care facilities or at the partner organisations’ premises. At the beginning of each interview, the patient was systematically reminded the purpose of the study and asked for oral consent to participate in accordance with the ethics committee protocol. Then, the patient was invited to express very freely on their experience of the pandemic since the first lockdown, from a broad and always identical opening instruction on which the team of researchers agreed on: "Can you tell us how you experienced the pandemic and the several lockdowns as a chronic patient?” In accordance with the semi-structured interview method (Beaud& Weber, 2010), the interview guide included several themes to be asked if not spontaneously addressed. One of these themes focused on the support network composition that the chronically ill person had benefit during the pandemic. All the interviews were recorded and fully transcribed.

2.2 Drawing the support network: a graphic contribution

While constructing our interview guide, we thought it would be useful to ask respondents to draw their support network during the interview. Initially, we thought that the drawing might help respondents to remember who played a resource role during the first lockdown. In addition, our research protocol included interviews with the people who played a supportive role for the chronically ill. We thought that asking the respondents to draw their support network at the end of the interview might facilitate our request to contact individuals in their network for another interview. Proposing the drawing at the end of the interview seemed also easier because a relationship of trust has been built up and would “reduce the blank page syndrome” (Girard et al., 2015, p. 52). By the end of each interview, even if this topic had been spontaneously addressed before, respondants were asked to draw their support network and to comment on its composition and specificities. The following instruction was given: "Could you please draw who played a supportive role for you during the first lockdown?" The interviewees were invited to draw on a blank sheet of paper or on the "whiteboard" function available through the videoconferencing software. Patients who could not access this function for technical reasons drew on a sheet of paper. The drawing was either sent by email or given to the researchers immediately after the interview. The use of the drawing was not compulsory and we made it clear that any respondant had every right to refuse to draw. Out of the 54 interviews, only 32 patients made a drawing of their support network. Amongst the 22 interviewees who did not draw: one patient refused, some asked to postpone the drawing after the end of the interview for technical difficulties or lack of time, but never sent their drawing back to the research team even after having been reminded to do so. Finally, researchers who conducted the interview chose not to ask certain respondents for a drawing. The reasons why drawings were not collected will be developed further below in the Limitations section.

2.3 Description of the Drawn Elements

In order to gather commentaries and information on the drawn elements, a verbal description was asked during the drawing process. According to Girard et al. (2015), “in view of the subsequent analysis, it is important to understand the meaning of the graphic elements drawn, by asking the respondents about their production”(Girard et al., 2015, p. 53). While the respondents were drawing we asked them: “Could you please tell us more about what you are drawing?” Just after each interview, investigators created a synthetic sheet in which they reflected on their observations of the interview process and the description of the emotional reactions of the respondent when the drawing was suggested.

2.4 Data analysis

Once these three types of data were collected, we conducted a comparative analysis of the interviews Once these three types of data were collected, we conducted a comparative analysis of the interviews and the drawings. We created descriptive tables listing and characterizing the drawn elements. We compared drawings with each other to identify their similarities and differences. Using the theoretical framework of social support (Thoits, 1995), we categorized the sources of support mentioned in the drawings: primary network/secondary network; formal/informal support; emotional/ informational/ instrumental support. We then noted their frequency and hierarchy: the most important, the most frequent, the most useful for the daily life, and whether they were orally mentioned or visible in the drawing by shape, symbols, lines and arrows. We noted the elements not drawn, but mentioned during the interview and the ones drawn. We used an analysis grid which always placed the drawn elements in relation to the respondents' discourse in order to limit bias of over-interpretation and misinterpretation of the drawings (Girard et al., 2015). The data triangulation of our three types of sources allowed us to enrich our qualitative analysis while remaining close to the voice of the chronically ill patients.

3. Avantages of Complementary Use of Drawings and Discourses

Three main contributions of this methodology to qualitative research will be highlighted.

3.1 Access to emotional dimensions

Getting adults to draw during an interview, as an unusual demand, led to emotional reactions from the respondents. We found out that those emotional reactions tend to increase adherence to and interest in the interview. In most cases, when we ask patients to draw, they were surprised and laughed. If the instruction of making a drawing might have appeared surprising at the beginning, it was experienced by many respondents as quite playful and increased the feeling of reliance to share more intimate details. A woman with a kidney disease, Rachel1, 27 years old, laughed and said “I even wanted to make a comic book of everything that happens to me [laughs].” Right after, Rachel focused on her emotional supports during the lockdown: her boyfriend and three close individuals with whom she shares difficulties of life. We noticed that the drawing instruction tended to bring childlike reactions, which led to a more progressive and less defensive narrative afterwards. When she first became aware of the instruments available on the Zoom® whiteboard, Marlène, a 52-year-old patient with cystic fibrosis told us “It's a pity, we can't put little men2 on! [laughs].” She then described the emotional support she received from a patient organization, and the deep empathy she felt for a man that she did not know, but who had suffered deep loneliness during the lockdown. Furthermore, drawing facilitated the expression of feeelings, which gave us access to emotional and affective dimensions. These dimensions are usually more difficult to reach in traditional forms of interviewing (Catoir-Brisson & Jankeviciute, 2014). Regis, a 65-year-old man with kidney disease diagnosed at the age of 12 and who described himself as anxious and distrustful of others, used a poetic expression when asked to draw: "yes, support is not only medical... is it possible to represent my network with a kind of intensity, like a sky with planets?" Immediately afterwards, while commenting on his drawing, Regis mentioned people and events that he had not mentioned before: the relationship with his girlfriend, with whom he does not usually live, was thus conflicting during the lockdown. By refering to symbolic and metaphorical dimensions, drawing made it easier for Regis to express emotions that were difficult to tell during the interview. Finally, the respondents took advantage of the multiple possibilities of the drawing activity to represent their emotions in a very structured way.

They used various graphic elements that helped them to mind map their words and thoughts: arrows emphasized the links between the presented elements; the positioning in the sheet space and the use of visual order of magnitude contributed to a very organized description of their support network. For example, the use of concentric circles visually allowed Hadrien to graduate the relatives who supported him according to the degree of intimacy and emotional closeness he shares with them (see Drawing 1).

Drawing 1 Example of Support Network Drawing: Hadrien, 46 years old with hemophilia. Captions: circle 1. him. Circle 2: “frère”: his brother and “cousines”: his two female cousins. Circle 3: “parents”: his parents, “enfants”: his teen-age daughter and “copine”: his girlfriend. Circle 4: “associatif”: the French Association for patients with Hemophilia and “professionals”: healthcare professionals

The participants’ discourse was then both rationally organized and more opened to emotional and affective dimensions. For these reasons, we believe it is worth using drawings when triangulated with their description and other parts of the in-depth interviews’ narratives.

3.2 When Drawing Raises Awareness

As a second advantage of the use of drawing, we noticed that it encouraged respondent reflexivity. The fact that the respondents drew at the time of the interview rather than having the drawing reconstructed by the interviewers afterwards encouraged the reflexive nature of the drawing.

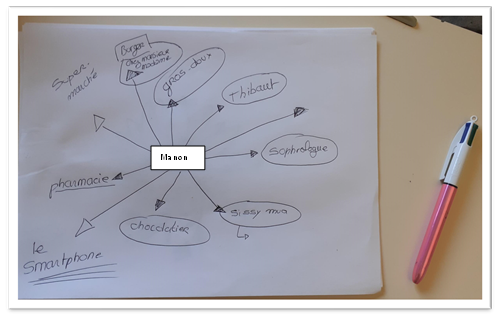

When they were drawing their support network during lockdown, some of our respondents became aware of things they were not aware of before. The drawing not only illustrated what was said previously during the interview, it often changed the course of the interview. While drawing their support network, some respondents realised that certain people who they thought should have played a supportive role were missing. We interviewed Manon, a 32-year-old woman with cystic fibrosis, by Zoom® on her cell phone while she was lying down on her hospital bed. She did not have the whiteboard option on her cell phone so she drew on a sheet of paper and sent us the picture after the interview (Drawing 2).

Drawing 2 Example of Support Network Drawing: Manon, 32 years old, cystic fibrosis. Captions: 1. “Thibault”: her boyfriend, 2. “Sophrologue”: sophrologist, 3. “Sissy Mua: a youtuber, 4. gros doux”: her cat, 5. pharmacie”: drugstore, 6. “supermarché”: supermarket “, 7. “Burger chez monsieur madame”: a burger restaurant, 8. “Chocolatier”, 9. “smartphone”.

On her drawing, Manon listed nine sources of support: her boyfriend, her sophologist, a famous youtuber, her cat, the drugstore, the supermarket, a burger restaurant. But once she had finished drawing her network, Manon was struck by the fact that she had not included her mother. It "strikes” her that her mother was not supportive of her during the lockdown:

In fact, it's strikes me, because my mum has not been a support. And I don't think that's normal, but at the same time... Well, when I think about it, she wasn't very supportive, that is to say that... um... She doesn't write to me much normally, so I can't include her in this, but it shocks me. (...) We may have called each other once, but um... For example, at the beginning to say: well, how are you doing, eh? But there wasn't that support of a mother towards her child every week, like: don't worry, it's going to be fine, we'll see each other soon. Because in fact there is no support in normal times, so it hasn't changed in fact.

The use of drawing made Manon realize that the lockdown had not changed the fact that her mother was not a support for her. The drawing revealed a blind spot of the interview: disappointment at the lack of support from people from whom one would have expected some support. By increasing reflexivity of the respondents, this method allowed us to explore new questions and led us to a better understanding of (non)support of the chronically ill during lockdown.

Unexpected Results

The third advantage of the combined use of interviews and drawings was that it can lead to unexpected results.

3.3 Contradictions Between Discourses and Drawings

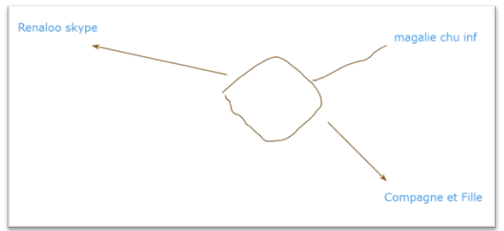

By comparing our three sources of data, we realized that there were contrasts between what respondents said during the interview, what was drawn, and the comments the respondents made while they were drawing. “By changing the angle of view,” drawing revealed “contradictory elements” (Girard et al., 2015, p. 51). During the interview patients mentioned people who played a supportive role for them during lockdown: their spouse, their family, their friends, their health professional, etc. But at the time of the drawing we realized that some of these people were not systemically included in the drawing or their support role was minimized because considered as “normal.” When analysing this contrast, we realised that this gap was most common for two types of actors: women and, to a lesser extent, health professionals. For instance, we met Reginald, 80 years old, suffering with kidney disease. Reginald is married and lives with his wife. At the time of the drawing he did not draw his wife on his network because he considered that the help she gave him is “normal” for a married couple: "Helping is not the word eh! We are married. Of course we help each other.” While the younger male respondents systematically included their wives in their drawings, we found that some put their wives' support into perspective by emphasising their own role in supporting them. We interviewed Renaud, 52 years old, suffering from kidney disease, who lives with his wife and daughter. During lockdown, he told us that his wife and daughter went shopping for him because he could not get out for fear of being contaminated by Covid-19. In this drawing, he included his nurse first, then in second place his wife and daughter, and in third place an association of kidney disease patients (Drawing 3).

Drawing 3 Example of Support Network Drawing: Renaud, 52 years old, kidney disease. Captions: 1. “magalie chu inf”: Nurse, 2. “Compagne et Fille”: Companion and daughter, 3. “Renaloo Skype”: Skype sessions with an organization of kidney desase patients.

While Renaud was writing “companion and daughter,” Renaud nuanced their support role, saying “in fact it was rather me who played a support role for my wife, because she was depressed during the first lockdown.” Renaud minimized his wife’s material support role, while emphasizing the moral support he gave her. This type of contrast between the oral accounts and drawings was indicative of a wider phenomenon, which was that support for the chronically ill patients at home was mostly done by women (wives, mothers, daughters) (Fernández-Peña et al., 2020; Kirchgässler & Matt, 1987), but their care tended to be considered as “natural” and was poorly valued. Here, the analysis of the contrasts between oral accounts and drawings revealed gender representations about social support (Cresson & Gadrey, 2004; Moujoud & Falquet, 2010; Tronto, 1987). Furthermore, most respondents mentioned their health professionnals as important supports in the medical management of their chronic illness. For instance, respondents with hemophilia told us that it reassured them to know that health professionals were "always there if needed" (Hercule, 22 years old). The support of health professionals was therefore present, but only if activated (Gage-Bouchard et al., 2015). During the lockdown, the majority of respondents had no particular health problems and waited for the end of the lockdown to seek medical support from health professionals (Lefève & Ricadat, 2022). At the time of the drawing, most of them included health professionals in their support network, but rarely in the first positions and rather in third or fourth position. The contrast between speeches, drawings and comments on the drawings about health professionals gave us insight on the specific dynamics of medical support for the chronically ill patients.

3.4 The Non-Human Support

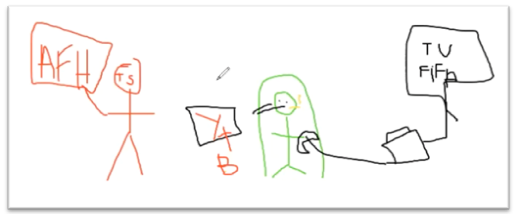

Finally, we discovered another unexpected result. When we asked our respondents to draw who played a support role for them, they draw not only people but also non-humans. We collected a lot of drawings with objects on them, media, food, restaurants, pets, drugs, medication, etc. All of these non-human elements were drawn by the chronically ill patients because they were considered as helping them during lockdown. For instance, we interviewed Hugolin, 19 years old, suffering from hemophilia and living in his parents’ apartment. During the interview, he told us that his mother went for his medication at the hospital’s drugstore during lockdown because he would not go out due to his illness. But during lockdown his relationship with his mother was very conflicted because of political disagreements. At the time of the drawing, Hugolin included first all his TV, videogames, YouTube, a cannabis joint in his mouth and finished with a representation of a member of a hemophilia patient’s organization (Drawing 4). Hugolin did not include his mother on his support network.

Drawing 4 Example of Support Network Drawing: Hugolin, 19 years old, hemophilia. Captions: 1. “TV FIFA”=TV softball video game, 2. “YTB”=Youtube, 3. “dessin d’un joint dans la bouche”= drawing of a cannabis joint, 4. “AFH TS”: French Association of Hemophilia and initials of a member

The supports mentioned by Hugolin were mainly non-human. Yet, literature about social support tends to focus on humans who provide the support (Bustamante et al., 2018; Fernández-Peña et al., 2020). The use of drawing revealed that support could come either from humans or non-humans. Our results highlight the need to broaden the definition of social support in qualitative and quantitative studies of support networks. As argued by the sociology of the actor-network, the entities that make up social networks would benefit from being analyzed without hierarchy or distinction as to their nature (Callon & Law, 1997). Triangulation of the data from the narratives and the network drawings brought to light some unexpected results. By revealing contradictions and paradoxes depending on whether important actors or resources appear only orally, on the drawing or in both cases, it highlighted which types of support were valued or invisibilized. By revealing the important support role of non-humans during lockdown, it contributed to a better understanding of the chronically ill patients’ experiences. Ultimateltly, the complementary use of drawings and narratives allowed for a more detailed and complex qualitative analysis of our research subject.

4. Limitations

This method has certain limitations. This section outlines the difficulties we encountered during our investigation and in incorporating the use of drawing into our interviews. Out of the 54 interviewees, 22 did not draw their support network. For some patients, asking to draw was quite impossible due to the specific conditions of the interview’s setting. For instance, four researchers on our team went to a dialysis facility out of Paris to conduct interviews. If patients agreed to talk without any difficulty, they were lying down and undergoing dialysis, which made the drawing impossible to do. Some of them asked the researchers to make the drawing for them by following their instructions. As they were not drawn by the patients themselves, we decided not to include these drawings in our corpus (Girard et al.,2015). Our experience has made us aware of the need to think beforehand about how to adapt the use of the drawing to conditions that are not always favourable. Drawing one's support network confronted some of our respondents with the realization that their support network was very thin. During our interviews with patients with mental health conditions, we noticed that most of them had very few supports in their close environment. The failures of their social and emotional network generated sadness and negative emotions during the interview. The use of drawings highlighted their feeling of loneliness and some of our respondents tore up their drawing at the end of the interview. Drawing may foster children or elders' expression (Katz & Hamama,2013; Woolford et al, 2013). On the contrary, our study shows that some adults may be distressed by drawing, because it may trigger less controlled emotional reactions than speaking. In order to prevent this effect, researchers should evaluate these limits and adapt the use of drawing to the emotional state of the respondents. In all the interviews, we gave respondents the opportunity to draw on a blank page or, if the interview was conducted by video conference, on the software whiteboard. Not surprisingly, researchers noticed that younger patients were more comfortable with the digital tools than the elder ones (Catoir-Brisson & Jankeviciute,2014). The middle-aged patients had to be secured and encouraged to draw on Zoom® at the beginning, yet were quite satisfied after making their drawing. However, elder patients - 70 years old or more - were reluctant to draw on a digital tool. Apart from the question of the digital device, we noticed that the older respondents were less comfortable with the use of drawing itself. Age and pathology variables for each patient were therefore discriminating in the use of drawing in our research protocol. Finally, the drawings gave us little insight into the dynamics of the support networks (Akerman et al.,2018). During the interview, the respondents told us about the evolution of their experiences throughout the health crisis. However, the drawing of the support network only describes the lockdown from March to May 2020. With the exception of one of our interviewees3, the drawings acted as a photograph of a moment in time without highlighting the evolution of the support network over time. As a result, we were only able to compare the drawings with the part of the interviews in which respondents talked about their lockdown experience. To counter this bias, we considered asking respondents to draw several drawings of their support networks: one before the lockdown, one during the lockdown, and one since. However, this methodological design would have made the interview considerably cumbersome, which is why we chose to limit to a single drawing by interview.

5. Final Considerations

The use of drawings during during adults' semi-structured interviews has many advantages for qualitative research. This method makes it easier for respondents to express their feelings and experiences. The analysis of the data collected in the interview and in the drawing revealed original results that would not have been detected only with the verbal interview. However, the use of drawing should be used with caution. In order to help investigators who wish to include drawings in their qualitative research, we have listed the considerations to be taken into account, before, during and after the fieldwork.