1.Introduction

Caring is an ancestral and universal process that accompanies the history of humanity, in a gesture of protection of the species, which aims at promoting a quality life for individuals and groups, particularly those in situations of greater vulnerability. Caring from a health perspective has a meaning of accompany and develop health (Hesbeen, 1998). Caring is understood here in a broad sense as an encounter, an accompaniment, and a resource that is made available to another person with a view to their health process. The caregiver, in an act of openness to another, is willing to accept them in their totality with their weaknesses and potentialities, to (pre)take care of this other who is vulnerable.

Looking at the caregiver, it is essential to distinguish formal care (professional care developed mainly by nurses) from informal or family care (unpaid activity provided by family or friends that arises in response to the need to meet the difficulty in performing activities of daily living) (Funk, 2019; Orzeck, 2016; Ume & Evans, 2011; Kim, 2009; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008). Becoming a caregiver is fraught with uncertainty and confusion "not only from the reservations that may be placed regarding the evolution of the ill family member's health status, but also regarding one's own ability to perform this role" (Pereira, 2011. P.30). The role of family caregiver is learned and lived throughout life by and through experience, through the relationship, through the skills and knowledge built in everyday life.

Taking on the commitment of caring for another in a process of accompaniment that does not aim at a cure, nor at improving the quality of life, but rather a work of maintaining capacities and slowing progressive losses in the expectation of an end to life with dignity, challenges the caregiver in their totality. The personal decision to take on this responsibility of caring for another until the end is determined by constellations of very diverse factors. Becoming a family caregiver is a complex and multifactorial experience (Orzeck, 2016; Pereira, 2011), culturally and historically inscribed, that configure the different forms of care. Still, caregiving has always been understood as an innate female activity that all women are expected to develop naturally (Fernandes; 2009).

For Cruz, Loureiro, Silva, & Fernandes (2010), the designation of family caregiver combines four factors, namely the degree of family ties (mostly spouses), gender (mostly women), physical proximity (mostly with whom the caregiver lives with), and, finally, affective proximity (predominantly through the marital or filial relationship). In addition, for some authors (Orzeck, 2016; Ume & Evans, 2011; Kim, 2009; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008), the decisive aspects in the decision to become a caregiver are the desire and willingness to care, the availability (due to unemployment or part-time work), being the target of the family's expectations or having a relationship of intimacy, involvement or love with the person in need of care. Other authors add that the assumption of the role of caregiver may be associated with a sense of duty/obligation and/or an act of charity or gratitude and/or retribution (Cruz et al., 2010). According to the National Alliance for Caregiving (2010), being a family caregiver goes far beyond the ties of consanguinity, it is someone with a significant personal relationship with the person being cared for, such as a partner, neighbor, or friend, and who agrees to perform an unpaid role. Caregiving is a dynamic process that varies over time and in intensity, it often takes a physical and emotional toll on carers and may inflict financial costs on them by crimping their labor market participation (Tur-Sinai, Halperin, Ben David, Lowenstein & Katz, 2022)

Caring indicates a way of looking after someone taking into consideration what is necessary for them to really exist, according to their own nature, in other words, according to their needs, their desires, their projects (Honoré, 2004). Caring is to exist and to be with the other, it is a surrender of oneself to the other, it is to be with the other in what the other is and not in what one is. (Honoré, 2004). To be a caregiver implies the abandonment of oneself, living within the time and space of the other.

In addition to a permanent concern for the other, being a caregiver implies attention and presence due to the need to perform from the simplest tasks, such as helping with the shopping and cleaning the house, to the most complex tasks, such as providing assistance with activities of daily living, feeding and/or hygiene. The degree of dependence of the person receiving care affects the type, number and intensity of the tasks to be performed (Tur-Sinai et al., 2022; Orzeck, 2016; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008). With regard to family caregivers, it can be said that the definition is associated with a significant personal relationship, regardless of the degree of relatedness, which provides unpaid care, and that the person being cared for is in a situation of frailty, dependence, disability and/or disease (Orzeck, 2016; Hillery, 2013; Blum & Sherman, 2010; World Health Organization, 2008).

The process of caring for another person who tends progressively to become more and more dependent until he finally dies, is a very demanding process that requires an increasing dedication from the caregiver who, in the end, become a family post-caregiver (Tur-Sinai et al., 2022; Orzeck, 2016; Ume & Evans, 2011; Kim, 2009; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008). The family post-caregivers are family caregivers who terminate their care relations in one of four ways: with the death of the person receiving care, with the institutionalization of the person, when another family carer takes over, or as the need for care diminishes (Tur-Sinai et al., 2022; Orzeck, 2016; Ume & Evans, 2011; Kim, 2009; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008).

In the total dedication to the other, the caregiver prioritizes the other, abandoning themself almost to the oblivion of who they are, besides their role as caregiver. When they stop being caregivers, and become post-caregivers, they are in rupture with themself, they don't know who they are. The family post-caregiver then protagonizes a set of transitions that require the incorporation of new knowledge, a change of behavior, and therefore a change of themselves in the new social context, which affects the state of mental health. With the social growth of informal caregivers, we are paving the way for the unraveling of the moment when the role of caregiver is disconnected and life is resumed in the void of caregiving. After the death of the person cared for, the family post-caregiver continues on their life path, in a work of self-reconstruction in the reunion with a world they abandoned, when they were absolutely dedicated to the other of whom they cared.

The nurses have accompanied and witnessed the whole process of caring which, after the death, serves as a real confirmation of all that has been experienced, achieved, and conquered. The post-caregiver is now required to reconnect with themselves and with the world, beyond the painful elaboration of the loss. This work of rebuilding their lives and reconnecting with the world is a painful challenge and has not been accompanied by nurses (Holdsworth, 2015; Pazes, Nunes & Barbosa; 2014; Nietsche, Vedoin, Bertolino, Lima,Terra & Bortoluzzi, 2013; Brownhill, Chang, Bidewell & Johnson; 2013).

With the social growth of caregivers, it is important to understand how they move along the path of caring. According to the Overview Report - Caring and Post Caring in Europe (2010), there is diversity in the support measures for European caregivers. In general, the measures adopted in each country reflect social attitudes towards uncertainty, inequality, transparency, citizenship and political and social development. Caregivers are involved in the management and process of care by the health team, so during the team's intervention with the person in a situation of vulnerability, they are also the target of intervention and support (Overview Report - Caring and Post Caring in Europe; 2010).

In general, after the death of the person under care, the care cycle ends, leaving the caregiver with no support. The caregiver is confronted with the end of their former world. Their entire focus of life suddenly disappears, nurses see no reason to maintain their presence, state support ends, and nothing they did before becoming involved in the care process makes sense now. Nurses can be central in this process by maintaining an integrated support to the family caregiver, following their trajectory. In the home setting the relationship between the family caregiver and the nurse has become closer and stronger, nurses have witnessed the whole caregiving process, and can become, after the death, partners in the grieving process (Holdsworth, 2015; Pazes, Nunes & Barbosa; 2014; Nietsche, et al., 2013; Brownhill et al., 2013).

In contrast to the abundance of research on the impact of caring on carers (Holdsworth, 2015; Pazes, Nunes & Barbosa; 2014; Nietsche, et al., 2013; Brownhill et al.,2013), research on after care remain quite sparse and limited (Tur-Sinai et al., 2022) This study aims to fill some of this gap. For a long time, the caregivers moved in the direction of what they were doing, and when they stop doing it, they are lost, in a painful void of re-learning how to put themselves in the center. How are these people doing after years spent caring, when they suddenly find themselves without the meaning of their lives? How do they reconstruct themselves on a daily basis?

The research paradigm emerged in response to this concern, from a phenomenological standpoint, with a particular interest in human experience, and how it gains meaning for those who experience it.

2.Research Route

2.1 Starting Question

"What is the lived experience of the post-caregiver in reconstructing everyday life?"

The experience of being a family post-caregiver and having ceased caregiving, after the death of the person cared for, is an event with unique meaning for each individual. The recognition of relevance in the voice of the family post-caregiver was focused on their story, their experience.

2.2 Aim

The aim is to understand the lived experience of the post-caregiver in the reconstruction of everyday life. With this knowledge it is intended to: illuminate, from the post-caregivers' point of view, the meaning they attach to care in the reconstruction of daily life; understand how post-caregivers restructure daily life after the death of the person cared for; explore the dimensions that post-caregivers consider essential for the reconstruction of daily life.

2.3 Methodology

This is a qualitative phenomenological study that allows access to the lived experience, to which it resorts to the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) proposed by Smith, Flowers & Larkin, (2009). IPA is a qualitative, experiential, and psychological research approach that emerges from several streams of knowledge, namely phenomenology, hermeneutics, and ideography. IPA can be characterized by a shared process (moving from the particular to the shared, from the descriptive to the interpretive) with principles (commitment to understanding the participant's point of view with a focus on individual meaning attribution) that are applied with flexibly according to the interactive and inductive framework of analysis. The search and interest for the lived experience of post-caregivers, and the meanings attributed to daily life, by the IPA approach, led to the use of the in-depth interview. This choice is underpinned by the purpose of entering the participant's lived world or allowing them to re-engage with their lived experience. The in-depth interview allows one to understand the meaning of a phenomenon under study as it is perceived by the participants, because they are the experts of their experience.

All steps of IPA were conducted: close reading, line-by-line reading and understanding of each participant; identification of emerging themes, simultaneously emphasizing convergence and divergence, first in the case and subsequently in the multiple cases; development of a dialogue between the researchers, discussing what that position might mean for the participants in a given context; development of a structure that illustrates the connection between the themes; organization of the material in a format that allows analyzing the data in order to lead to the emergence of the themes; conducting collaborative analysis; development of a narrative with a detailed description of all comments and reflection on individual perceptions, conceptions and processes. The collaborative analysis stands out for its importance in the joint reflection of the narratives that raised the level of understanding, fundamental for the abstraction process for the identification of the themes.

2.4 Recruitment

Eleven participants, who had been previously cared for by Long Term Care Teams in the Lisbon region and who had ceased caring after the target's death for at least one year, were accepted to participate in the study. The approach to the Long-Term Care Teams was based on the positive recommendation, to the development of the study, by the Ethics Committee. The participants gave their prior consent to conduct the interviews, which were carried out in places and at times chosen by them. The interviews were conducted between January and May of 2015.

The participants are essentially women, seven widows and two daughters, and two men, widowers. The age of the participants ranges from forty-seven to eighty-one, and the length of time they have been a caregiver ranges from three to fifteen years. The death of the person cared for occurred mostly at home. The time of cessation of care is between thirteen and thirty months. In relation to work, most are retired. Three participants are employed.

3. Reflection of Experience:

The participants' lived experience in reconstructing daily life emerges from the description of their experience of daily life. This experience of daily life unfolds in the dynamics of their simultaneous relationship with the past (remembering what was lived) and with the present, in the recognition of themselves, in the permanent response to return to the world and life, and in the glimpse of an imaginary future of challenges and uncertainties. It is in everyday life that the participants reconnect with themselves, with others, and with the world. However, the reconstruction is an individual process, the themes that illustrate the reconstruction of everyday life are not static, but plastic. Each participant has their own movement in simultaneity.

The family post-caregiver reconstructs their daily life in effort, still drowning in the memories either of the other who is no longer present, or of the time and space in which he or she cared for that other. At the same time that, they are centered on themselves, they are confronted with the need to return to the world and life, with the challenges and uncertainties of the future. People find themselves forced, after death, to the task of reconstruction, being still overwhelmed by care, by physical memories of gestures, and by a certain organization of time and life. This memory is present at the same time as they think of themselves, facing the new situation they are living, who they are, what they want, what the meaning of life is, what their projects are, what returning to life represents.

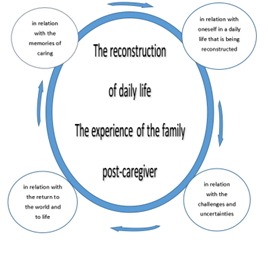

The return to life happens in a framework of uncertainty about the future, because daily life is changing, what one encounters has changed, but one's self is also different. Everything is experienced in ebullience and simultaneously. Simultaneity introduces the perception of the whole, of a constant experience of family post-caregivers in relation to thinking and remembering (relationship with the memory of caring), in relation to the recognition of oneself (relationship with oneself in a daily life that is being reconstructed), in relation to acting (relationship with the return to the world and to life), in relation to what one imagines for oneself in the future (relationship with the challenges and uncertainties of the future). The reconstruction of daily life happens in the emergence of all this, in a simultaneous relationship. This movement is translated in the essential structure; that of the Experiences of the Family post-caregiver in the Reconstruction of Everyday Life (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Essential structure that translates the Lived Experience of the Family post-caregiver in the Reconstruction of Everyday Life

Source: Elaborated by the author

The four themes, we found, have a unique expression for each participant. Each one is simultaneous in relation with the memories of caring (1), in relation with oneself in a daily life that is being reconstructed (2), in relation with the return to the world and to life (3), and in relation with the challenges and uncertainties of the future (4). All of this process of being in relationship happens in a continuous exercise of reformulation and balance. It is in the dynamics of this simultaneous relationship that they reconstruct their daily lives. While bearing the memories of caring, they recognize that they are different, in an ever-changing daily life. They respond to the demand to return to the world and to life challenging themselves in the projection of the future.

Relationship with the memories of caring (1)

The participants, in what concerns their memories of caring, reveal a transformative experience. Caring represented putting life behind, not stopping, and having a sense of powerlessness. "I put my life completely behind me, to be there in it, centered on my mother" (Fatima). They put their life completely behind, life itself was put on hold, they were put on hold themselves. They couldn't be who they were was anymore. The focus on caring conditioned time and life as it was, because those who care don't stop and don't stop to think. In the swirl of caring, where the feeling of helplessness is constant, even with all the surrender, it is not possible to avoid the aggravation or the dying process of the one being cared for. Watching another person wither away and die deeply marks the memory of caring. After all, the suspended life that has passed has left marks that are fixed in memories, and this is present in the reconstruction of the participants' lives. Some reveal that they feel transformed and consumed by caring. Caring for the other revealed itself as a prison, an absolute dedication that imposed a neglect of the self. Life was put on hold, left completely behind. The memory of not stopping persists and some participants say that sometimes they still feel the routine that was imposed for so long.

A sense of powerlessness emerges from following the suffering and degradation of the other, and there is an internalization of suffering. Time is significant aspect, not only regarding the learning process of caring, but also regarding the duration of the role of caregiver, which for most of the participants was long. Throughout this period, the routines of daily life were centered on the process of caring, now life rebuilds itself, and some refer that they still feel the routines embedded in them. In the eyes of the participants a daily life of loneliness emerges now, having suffering as a backdrop. "The understanding of what is lived always has a personal meaning" (Caeiro, 2010, p.27). For the participants, being in relation with the memories of caring becomes possible now, in an exercise of retrospectivity. Now, there is the possibility to look back at everything that has happened and interpret it, understanding what it all meant to them.

In relation with oneself in a daily life that is being reconstructed (2)

In the participants' discourse, being in relationship with oneself in a daily life that is being reconstructed, constitutes a time of identity construction, in which they realize that they have changed and that life has not been waiting for them. The everyday life is different, but they, the participants, are also different. "The self lasts so little that it changes in each of its experiences (...) we only become ourselves when we think and live accordingly the changes that we experienced. (...) There are experiences, everytime when through them and in them I change myself. I am another self because I have lived this or that." (Caeiro, 2010, p.43). Using Caeiro's words, the participants, in their relationship with themselves in a daily life that is being reconstructed, recognize the modification of themselves. When they are confronted with themselves, they discover that they are alone (over time they have reduced their social relationships), that they are not the same, that the house has become their world, shelter and trust, and that everyday life has become strange (which for the participants was suspended in time). "We don't stay the same, I was a cheerful person, now we are no longer the same, we have become sadder about life with everything. Having seen and witnessed his destruction, we change (Ana). Loss of loved one whom they care brough up the loss of past self which they grief. This is one form of transformation brough by the caring process.

In relation with the return to the world and to life (3)

In the relationship with the return to the world and to life, making use of the words of Caeiro (2010) everything happens in the sense of letting it go. They let themselves go in life, and life goes on, they are carried by it. That is the fundamental root of the experience they have of the being in life, the participants are carried by life. This carrying happens in a context of suffering that takes them back all the time, they feel a sense of emptiness not only from the absence of the other, but also from the absence of activity, seen by some as a relief. "We no longer had to get up at the right time for breakfast, the diaper, the baths, none of that. (...) My mother, her being there, was in a way a goal for me, and when you have that feeling of loss, sometimes, especially when I'm alone, I feel that I have no goal. " (Emília). The transformation or estrangement contribute to the way they experience the return to the world and to life. They do it slowly, accepting that they are different, that life has changed. this return in their speeches one can identify the processes of how was the returning to life, what made it easier, and what manifested as an obstacle. After the loss of the person under care the participants experience a deep lack of meaning, and now the search for new meaning is made by and through suffering. Although, the participants report that through the new routines and with the help of the support network, they have reconnected with the world. As Josefa say “I started going to church, then I started going to gymnastics. I did it all slowly.”

In relation with the challenges and uncertainties of the future (4)

For the participants, being in relationship with the uncertainties and challenges of the future means undoing the suffering, living one day at a time, managing the expectations and appeals of everyday life, and finally building a future, in a message of hope for the life to come. "It is necessary to counter with an enriched wisdom that dialogues with the transformations we are going through." (Mendonça, 2016). Participants, are in dialogue with themselves integrating all the transformations they have gone through. In "undoing" grief, participants integrate their transformations, some have nitted, some have walked, some have hiked, each has turned to themselves, all have mourned, all have done a work of rebuilding themselves. "We have to try to renew, I don't know how yet, I haven't found it, but I will find it for sure" (José). Some participants envision future perspectives that include taking care of other family members, such as grandchildren, for example, while for others it means trying to return to the labor market. But many, also recognizing their aging process, especially the older ones. Those, look to the future with doubt about how long they have left to live, and what they expect from the future is to wait for death. It is in the elderly that the loss of meaning gains relevance. It's the elders who report only waiting for death. Each participant's life expectancy is projected into the future, so there are younger participants who imagine themselves looking for work, new relationships or accompanying younger generations of the family.

Previous studies with post-caregivers highlight their vulnerability especially in terms of their physical and mental health (Tur-Sinai et al., 2022; Orzeck, 2016; Ume & Evans, 2011; Kim, 2009; Larkin, 2009; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008). The findings of this study are in line with previous literature (Tur-Sinai et al., 2022; Orzeck, 2016; Ume & Evans, 2011; Kim, 2009; Larkin, 2009; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008). Although this study brings the phenomenon of the reconstruction of daily life. From the participants' point of view, the meaning they attach to caregiving, in reconstructing everyday life, is putting life behind, not stopping, and having a sense of powerlessness. As the participants restructure daily life after the death of the person cared for, they feel a sense of emptiness (not only from the absence of the other, but also from the absence of activity that for some is a relief) and conforming that they are different and that life has changed. The participants look back retrospectively at what life has been like, in a glimpse of what it can become. "We carry life forward. We are carried by it. That is the fundamental root of the experience we have of the being, in life " (Caeiro, 2010, p.33).

Being a family caregiver is something legitimized socially, but family post-caregiver is not. Furthermore, all legally provided support for the family caregiver ceases with the death of the person cared for. The participants do not define themselves as post-caregivers, having care is not something that defines them as a person. Caring was a role they played and have now abandoned. Caring was an experience, a transformative experience that has ended. Participants do not recognize it as part of their identity, although they do recognize it as a source of transformation of themselves. For the participants there is a recognition of change, a change in themselves, in everyday life and in the way they look at the world, the other they cared for was part of themselves and now the call of everyday life is the search for self.

4. Final Considerations

The phenomenon explored shows how the recognition of self happens in the family post-caregivers, in their life projects, in the re-learning of living, in the new space they find themselves. This study shows the vulnerability of the family post-caregiver, who does not have a legitimized identity (Castells, 2010), who reconstructs daily life in the simultaneity of being in relationship with himself, with others, as the world and with the future.

This study shows that the reconstruction of daily life takes place simultaneous in relation with the memories of caring (1), in relation with oneself in a daily life that is being reconstructed (2), in relation with the return to the world and to life (3), and in relation with the challenges and uncertainties of the future (4). Participants are marked by memories of caring and grief remains in the background of life that is unfolding. Processing grief and loss is described by the participants in the theme of being in relationship with oneself. On the return to life, there is a lack of project, because the project was to care for the other, who is gone. In addition, old age weighs on the anticipation of possible futures and some participants what they project is to wait for death and fulfill God's will. These findings highlight previous literature (Tur-Sinai et al., 2022; Orzeck, 2016; Ume & Evans, 2011; Kim, 2009; Larkin, 2009; Orzeck & Silverman, 2008) especially in the vulnerability of the post-caregiver and his fragility in the reconstruction of daily life.

Phenomenological studies make possible to give visibility to the lived expression of problems, which provides health professionals spaces for the projection of their professions through the creation of new care offers in partnership with local communities (Smith, Flowers & Larkin, 2009).

This study allows nurses to have a better understanding of the caregivers and allowing them to reflect on new responses that nursing can provide to the post-caregivers from a person-centered care perspective.

Through this study, nurses will be able to access the lived experience of these post-caregivers and challenge themselves in the provision of care, enhancing the expertise in care, improving their care intervention in hospital or community settings. Nurses can remain present in this journey of loss of habits acquired in the process of caring, maintain a presence with the post-carers, accompanying their recognition of themselves, of others and of the world, providing support. In the process of caring, the post-caregivers were, lived for and with the other, accompanied by the nurses who legitimized the lived reality. In the return to life, nurses can maintain a presence, a meaningful presence, being and accompanying the simultaneity processes those post-carers reveal in the narratives of growing and transforming grief processes, and with the need to experience and integrate new paths (Puigarnau, 2011).

This study may challenge nurses to reinforce support networks for family post-caregivers with the connection and involvement of partners and social resources. The continuation of support for post-caregivers through support groups in the communities, which contribute to their healthy aging, mobilizing various community resources in this process. Provide support for returning to work through the articulation of social workers.