1. Introduction

Diabetes is on the rise across the globe. In 2021, an estimated 537 million people were living with diabetes, or 1 in 10 globally (International Diabetes Federation [IDF], 2021). Without urgent action to address this epidemic, the global burden of diabetes is projected to rise to 643 million by 2030, and 783 million by 2045, with the largest increase expected to take place in low- and middle-income countries (IDF, 2021). The reasons for the escalating epidemic of diabetes are multiple, including increasing rates of obesity, physical inactivity, unhealthy eating habits, sedentary lifestyles, urbanization, and economic development, in addition to an aging population (Chatterjee et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2018; Zimmet, 2017).

In Liberia, a low-income country, the prevalence rate for diabetes is estimated to be 2.1% (IDF, 2021). This rate likely represents a gross underestimation of the burden of diabetes in Liberia, given the limited disease surveillance infrastructures that exist there. More than half of this estimated 2.1% of people living with diabetes are undiagnosed - underscoring the grave burden of diabetes in Liberia (IDF, 2021). The root cause of the burden of diabetes in Liberia are multi-factorial and include a series of civil wars (1989 - 1996 and 1999 - 2003) and the West African Ebola virus disease outbreak (2014 - 2015) (NCDI Poverty Network, 2018). Both circumstances have led to major disruptions to the Liberian health care system and rendered it incapable of responding to the insidious threat of non-communicable diseases like diabetes (NCDI Poverty Network, 2018). As a result, people living with diabetes in Liberia experience significant challenges to accessing social, economic, and health-care resources to manage their illness.

The current data on diabetes in Liberia helps us understand the state of the disease at a population level (IDF, 2021; Ministry of Health and Social Welfare Republic of Liberia, 2011; Ministry of Health Republic of Liberia, 2016; World Health Organization, 2016). However, the voices and stories of people living with diabetes in Liberia are almost entirely absent from this data. Currently, only one study by Adler et al. (2021) provides findings on the experience of participating in diabetes self-management practices for people living with type 1 diabetes in Liberia. Given the dearth of qualitative literature on this phenomenon, the purpose of this paper is to present results of a critical hermeneutic study that explored the experiences of people living with diabetes in Liberia. In the following paper, we will present the research design, data collection and data analysis process, the findings, and implications for practice and policy.

2. Description of the Study

2.1 Methodology and Methods

We used critical hermeneutics as our methodological approach to interpret participants’ experiences of living with diabetes. Hermeneutics is the analytical process of finding meaning in written text (VanLeeuwen et al., 2019). ‘Critical’ alludes to the idea that all interpretations must evaluate the power relations that are inherent in human experiences (Given, 2012). Critical hermeneutics is rooted in philosophical traditions as described in the works of Hans-Georg Gadamer (Gadamer, 1990), Paul Ricoeur (Ricoeur, 1981), and Jurgen Habermas (Habermas, 1984).

As a method of data collection, we used photovoice. Photovoice was developed by Wang and Burris (1997) and inspired by theoretical literature about critical consciousness - in particular the works of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (Freire, 1970), feminist theory (Frankenberg, 1988; Smith, 1897), and documentary photography (Ewald, 1985; Hubbard, 1991). Photovoice involves taking, discussing, analyzing, annotating, and displaying photographs of everyday health and work realities (Wang & Burris, 1997). The synergy between critical hermeneutics as a methodology and photovoice as a method allowed us to explore the depth of participants’ narratives - interpretating their stories for what was common, what was unique, and what was unspoken (VanLeeuwen et al., 2017). Ethics approval was obtained from Queen's University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (TRAQ file #: 6034868) and University of Liberia Institutional Review Board (Protocol #: 21-11-289).

As this paper is part of doctoral thesis work led by the first author, the first author took the lead role in data collection and data analysis for this research project. Therefore, we acknowledge the first author’s positionality as female, middle class, and a Canadian Liberian.

2.2 Setting, Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited from Redemption Hospital in Monrovia, Liberia. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, we partnered with Adventist University of West Africa (based in Monrovia, Liberia) to help facilitate recruitment and participant interviews. Adventist University of West Africa distributed recruitment flyers and worked alongside nurses to identify potential study participants. We used a purposeful sampling technique to select individuals experienced with the phenomenon under investigation. Inclusion criteria for the study were (a) adults (18 years plus); (b) diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes for two years or more; and (c) able to understand and speak English. A total of 10 participants were enrolled in the study (see Table 1 for participant demographic characteristics).

*Pseudonyms are used; M, Male; F, Female; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; C/U, College, or University; VT, Vocational Training; HSG, High School Graduate; <HSG, Less than High School Graduate

2.3 Data Collection

Data were collected by the first author from April 2022 to May 2022. All data were collected virtually via ZoomTM (a conference room at Adventist University of West Africa was the physical space that participants accessed to participate in scheduled ZoomTM meetings). Data collection was divided into four phases. First, participants were given digital cameras and asked to take a maximum of 25 photographs reflecting their experiences of living with diabetes. Second, participants chose five photographs and discussed them in the first semi-structured interview session, which lasted approximately 90 minutes. Third, a second semi-structured 45-minute interview session was conducted to clarify and follow-up on issues raised in the first semi-structured interview. Fourth and finally, participants chose two photos to discuss in two focus group sessions held to collect narratives on participants’ collective views. Each focus group session lasted about two and a half hours.

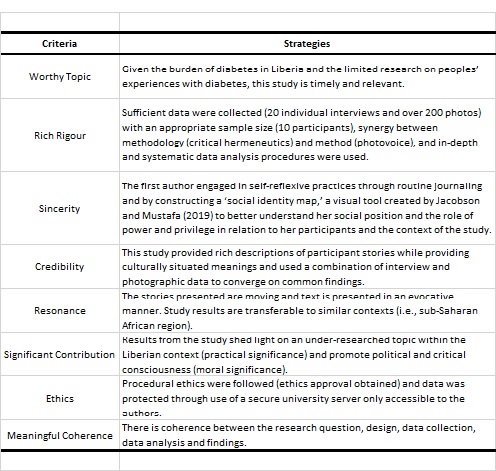

For the purposes of this paper, only the results from the individual interviews will be discussed. The results of the focus group will be presented in a separate paper. The interview sessions were transcribed verbatim using Otter.ai©, and independently proofread for accuracy by two researchers. De-identified data was stored on a secure server at our university and was only accessible to research team members. The trustworthiness of the study is presented in Table 2 using the criteria for qualitative quality by Tracy (2010).

2.4 Data Analysis

In our analysis of interview and photographic data, we used van Manen’s (2014) thematic analysis and Capous-Desyllas and Bromfield's (2018) arts-informed approach to identify emergent themes. Our process was as follows: we listened and replayed the audio-video recording while engaged in reflexive writing. Then, we read and re-read interview transcripts, initially as a whole, then as sections, then as phrases. Next, we examined photographs and captions, looking for shared thematic moments between photographs and interview transcripts. Finally, as major themes were uncovered, we followed the interpretive process of writing and re-writing, and engaged in a back-and-forth movement between the whole and the parts, until a naïve understanding was revealed (van Manen, 2014; VanLeeuwen et al., 2017). We engaged with our data in a tactile manner, arranging and re-arranging photographs and quotes on a whiteboard to enrich our interpretation (Capous-Desyllas & Bromfield, 2018). Throughout the analysis, it was important to remain conscious of our hermeneutic positions, that is, where we are situated in relation to the social, economic, political, cultural, and historical context of our study (VanLeeuwen et al., 2017). This iterative process with the data allowed us to gain a profound understanding of the situation of people living with diabetes in Liberia.

3. Results

We identified three themes that answered the question of what is it like to live with diabetes in Liberia: living with diabetes means living with 1) food insecurity, 2) trying to access a health care system that was not built to respond to diabetes, and 3) using faith to cope and foster hope.

3.1 Living with Food Insecurity

For those living with diabetes in Liberia, access to safe, sufficient, and nutritious food is essential for diabetes self-management. In this study, participants shared stories about worrying about obtaining food, compromising the quality of food, skipping meals, and experiencing hunger. Many participants found themselves caught between competing priorities such as procuring food, purchasing prescribed medications and supplies, and seeking medical care, putting them at significant risk for both short-term and long-term health consequences (Gucciardi et al., 2014). Many would forego medications and diabetes-related supplies (i.e., glucometers and test strips) to afford food. Others purchased cheaper, nutrient-dense foods to cope with the challenges of food insecurity. Overall, when participants found it difficult to access sufficient food, tailoring their food selection to diabetes-friendly choices (foods high in protein, vegetables, and fruits, and low in fats and carbohydrates) was difficult, if not impossible.

Maggie, a woman who has been living with diabetes for 14 years, has ample experience with the challenges of diabetes management when compounded with food insecurity. Maggie’s diabetes journey is unique in that her spouse is also living with diabetes, so they have learned how to cope together in managing their illness. Maggie makes all attempts to tailor their food selections to their dietary requirements but admits that fluctuations in the local markets concern her and can sometimes impede their ability to be adhere to their prescribed diet. She explained:

Yeah, at times you worry, because, if you can’t you have to worry about it, because when you go on the market and you need that food, but you go and you don’t see the food you eat, you have to worry about it.

When Maggie speaks about food, she is referring to the common diabetes-friendly dishes she makes like green plantain soup, green plantain dumboy (plantain boiled and pounded into a ball) with pepper soup, or bulgur wheat with a traditional Liberian stew.

The constant worry about access to food was also shared by Soso Favor, a self-employed mother of three who was diagnosed with diabetes about two years ago. She shared:

Yeah, I will not lie to you. Sometimes, it worries me. That is what I am saying, I will not lie to you, sometimes, it worries me. Like today own now, if I get today own now, when I eating today own now, then I will start to think, ahh God, let tomorrow too be like this, let me get tomorrow own.

The consequences of food insecurity for people like Soso Favor is increased consumption of unhealthy foods, foods with high glycemic index, which significantly increases one’s risk for diabetes-related complications (e.g., lower limb amputation, kidney failure, and blindness). In a resource-limited setting such as Liberia, living with the complications of diabetes coupled with the challenges of food insecurity can mean marginalization and isolation, resulting in poorer quality of life and worse health outcomes.

Sekou, who was diagnosed with diabetes four years ago, knows all too well the challenges of living with the complications of diabetes. Sekou has diabetic retinopathy, a common complication of diabetes that leads to vision loss. As a result of his impaired vision, he has been unable to work since his diagnosis. He relies entirely on his sisters for financial help and the kindness of friends in his community. During periods of extreme financial hardship, he experiences hunger. Sekou explains:

No, when I don’t have money, I don’t eat, I don't worry self, the only thing I worry so much for is my health. I always be praying throughout, until sleep can come in my eyes, that what I can do, most often, I just be praying. If I don’t eat, I just be praying, just for me to come to myself and sleep, then in the morning I wake up.

The combination of hunger and diabetes is particularly dangerous as it can lead to severe hypoglycemia and, in some cases, death. This is a frightful experience for Liberians living with diabetes, as very limited systems are in place to address this situation. In the absence of community food programs, people like Sekou who live with diabetes in Liberia are forced to go without eating. If they are fortunate enough to survive the short-term consequences of hunger (i.e., hypoglycemia leading to coma, seizure, or death), repeated experiences of hunger can place people living with diabetes at risk for long-term consequences such as cognitive impairment.

Although experiences of hunger were the most distressing aspects of being food insecure, participants also reported concerns about the limited food options that health-care providers recommended for their dietary regimen. Participants were generally advised to avoid staple Liberian foods with high glycemic indexes like white rice and cassava dumboy and to replace them with low/medium glycemic index foods like bulgur wheat and green plantain, as the latter provide better blood glucose control. However, it was not always possible to adhere to these recommendations amid financial challenges, as foods like bulgur wheat and green plantain were far more expensive than white rice and cassava. When discussing a photo he took of his evening meal (Figure 1), Tenden, a retired hospital executive explains what he does when he is faced with financial hardship:

If I want to eat the rice, my wife put the rice on a fire and put water on it, she will let the rice boil. Then she takes the starch and waste it. She put clean water on the rice again and wash it. Then she wastes it and then she let the rice steam. It shouldn’t be soft, it should be, you know, just normal rice. Then the rice does not contain no more starch.

3.2 Trying to Access a Health care System not Built to Respond to Diabetes

Liberia’s protracted 14-year civil war coupled with the Ebola virus disease outbreak left a devastating impact on the country’s health care system. Both events disrupted health services and further weakened resources in a country where they were already limited (Fall, 2019; Lee et al., 2011). Consequently, the health care system continues to struggle to provide basic health services, especially for individuals living with chronic illnesses like diabetes.

In this study, participants described a general perception of neglect regarding health services for people with diabetes compared to other conditions. John Sumo, a 56-year-old retired health-care provider explained:

Yeah, like HIV, they have a center for it and other sickness they have a centre. So, if you have a data base, ministry of health have a data base, you see this sickness it killing a lot of people then you can try to, you know, get hold of it. But it’s not like that here.

Participants pointed to poor access to diagnostic equipment, an inadequate number of trained diabetes specialists, a lack of diabetes programs, and a lack of awareness of diabetes as evidence of neglect. Maggie voiced her frustration regarding the lack of advocacy organizations for people living with diabetes in Liberia:

No support in the sense that by right, we should be having diabetes society program in Liberia. Now we don’t have any. Once, I went to [name of hospital], I went to a workshop there. But since that time, because I far from that area, but since that time they never had workshop on diabetes, they never put the diabetes society in Liberia together for me to attend. So sometimes I feel downhearted but with God everything is possible. So, I’m moving on with my life, taking my treatment.

Maggie’s frustration with the limited awareness of diabetes in Liberia, which is essential for prevention, management and control of the disease was palpable in the conversation in the room.

Although feelings of neglect were prevalent among participants, it was worsened by the high cost of medical treatment shouldered by people with diabetes and their families. John Sumo voiced his frustration with the local hospital and the lack of supplies and resources allocated to people living with diabetes. He was particularly disappointed that his local publicly funded hospital was routinely out of anti-hyperglycemic medications, sharing:

Sometimes at the hospital, they don’t have all the medicine. Yeah, so the whole frustrating part is when you get there, and the medicine not there, you have to pay for your prescription. With the prescription, he can just write it for me, and I will try to get it, because I want to be treated. They give you prescription, then you go to the drug store.

This sentiment was also shared by Welee, a 54-year-old widow who works as a nurse aid in a publicly funded hospital. Welee understands the complex situation at hand - constrained health-care resources resulting in unjust financial burdens for people with diabetes. Welee explains, “[name of hospital] is a government hospital and this medicine they give it to us free. But sometimes because of the many patients, when you go, no medicine at all. Sometimes two, three months, you find it difficult.” When asked whether diabetes medications were currently available at the hospital where she works, Welee confessed, “Right now as I speak, in the hospital, we don’t have no Metformin, no diabetes medicine is there now.”

Since participants could not access diabetes medications when they sought care at their local hospital, community pharmacies were their go-to place to purchase medications and supplies. Community pharmacies played a pivotal role in providing access to diabetes treatment that was otherwise inaccessible at local hospitals. Although participants had to pay out-of-pocket, they found community pharmacies to be considerate of their financial situation. While discussing the photos she took of her local pharmacy (Figure 2), Soso Favor recounts:

Yeah, this pharmacy has been a great help to me and my family. Yeah, especially when it comes to me, my drugs, since I don’t have money, I was going to this drug store. He would help me, give me the drugs and then when I sell, I carry the medicine money to him, me and my children. That’s why this drug store has been a great help to us.

The gaps in diabetes services and care that participants experienced with publicly funded hospitals were often addressed, albeit temporarily, by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). NGOs have a long history of working in Liberia, playing a pivotal role in the provision of direct health services to the most vulnerable groups. After the 14-year civil war in Liberia, NGOs rose to greater prominence in their role of working with Liberian communities to strengthen the health care system that was severely damaged by the civil war. While NGOs have addressed some of the health challenges experienced by Liberians, they are just temporary bandages to the structural problems in the country. Yei Kadeh captures this phenomenon perfectly, saying:

When MSF [Médecins Sans Frontières] was there, anytime you go, they prescribe your drugs, you will get it, if even it is not there, MSF will make sure that you get those particular drugs. But now, things are so difficult, you go to the window to get your drugs, you will not even get your drugs. So, you have to go to either a bigger pharmacy, or nearby pharmacy, or drugstore that you will be able to get your medication. It is not easy, yeah, because times are so hard now.

Unquestionably, these short-term aids by NGOs are insufficient for building a health care system that responds to the needs of the chronically ill, including people living with diabetes.

In Liberia, Christians make up approximately 85% of the population, followed by Muslims at 12%, with the remainder of the population identifying with tribal or indigenous beliefs (Central Intelligence Agency, 2021). Although participants did not explicitly state their religious affiliation, a majority referenced the Christian bible and biblical texts when speaking about the role that their faith played in their ability to cope and exhibit hope throughout their illness journey.

In this study, participants spoke boldly about their faith and the role it played in their understanding of their illness. Sabbah, a 44-year-old self-employed man who had been living with diabetes for five years, shared:

My belief in God can help me to overcome this identical sickness… Even though doctor say I’m sick, but I’m saying that even though, God say by his strips I am healed, so I believe it, that I’m not sick.

This tension between faith and medicine was palpable in many conversations with participants. When discussing a photo she took of herself reading the Christian bible (Figure 3), Yei Kedah, age 54, shared her perspective on the intersection of faith and medicine:

In the evening, we have our devotion and sleep. Because if at all, even you doing the medical, you have to do the spiritual, so it shows that when you are doing the medical treatment, you have to do the spiritual treatment. So, I have to talk to my Maker to help me.

Participants also spoke openly about the role their church community played in supporting them through their illness journey. Mary John has been living with diabetes for about two years and found her church members quite supportive, with members often offering dietary advice to help her manage her diabetes. She explained:

They can tell me, you got to watch the diet, they say watch the diet, when you know that sugar, you know, like you eating sugar food, you got to try to avoid it, eat food that don’t have sugar, because certain age you reach, majority of us, to the Kingdom Hall have that problem too. So, I think last week, he said, watch your diet, my friend was telling me, from the Kingdom Hall, saying, try to watch your sugar, I said yes, that’s true.

Sabbah expressed a similar sentiment, speaking candidly about how particular members in his church went the extra mile to help him financially. He explained:

They helped me with 10 dollars [United States Dollar] to go and do the test, after the person realized that my eyesight was getting dim. So, the person asked me to go and do the test to find out why my eyesight was getting dim, and I did the test. And I reported the case to the person and said that it was the sugar that went on high that why it affected my eyesight.

Amid trying to cope with the challenges of diabetes, a vibrant sense of hope was apparent in all the conversations with participants. The participants’ hope was driven by their faith - a sure confidence that their health would be restored one day, and they would live well. Victoria Weah captured this transcendent hope, saying, “I give God the glory, so long, there is life, there is hope. That's why I still living, I know God will make a way.”

4. Discussion

The themes presented in this paper represent participants’ collective experiences of what it is like to live with diabetes in Liberia. The participants’ stories about food insecurity, access to health care services, and spiritual beliefs helps us understand their individual experiences within the wider context of the social, economic, cultural, and political atmosphere of Liberia. In our review of the literature, we found several studies that reported findings that parallel our own. Adler et al. (2021) similarly explored the experience of living with type 1 diabetes in Liberia, collecting narratives from people living with type 1 diabetes, health-care providers, civil society members, and policy makers. For example, similar to our study, they found that patients with type 1 diabetes modified their meal size by eating smaller quantities of white rice rather than avoid it to deal with food insecurity. The study also found that the high cost of diabetes-friendly foods such as bulgur wheat and green plantain was reported as a major barrier for diet adherence (Adler et al., 2021). Nsimbo et al. (2021) also examined food insecurity and its relationship with glycemic control in people living with diabetes in South Africa. They found that participants with poor glycemic control were 5.38 times more likely to have experienced food insecurity compared to participants who had good glycemic control. One explanation for this finding, as was also observed in our study, is that competing priorities (e.g., food, medication, and supplies) often make people living with diabetes vulnerable to poor food choices. The consequence of poor diet is poor glycemic control, and ultimately worse diabetes outcomes.

The second theme of our study centered around neglect of diabetes-related services in Liberia and difficulty accessing them. Song and Lee (2021) made a similar finding in a systematic review examining factors influencing the effective management of diabetes during humanitarian crisis in low- and middle-income countries. They found that during acute humanitarian crisis, blood glucose control worsened due to the inaccessibility of diabetes medications, either because of blockage of supplies due to armed violence or the sudden rise in patient load at health centres. Similar barriers related to access to diabetes care have also been documented in recent conflicts in Syria (Khan et al., 2019) and Ukraine (Alessi & Yankiv, 2022). In both contexts, the destruction of health infrastructure such as pharmacies led to disrupted services, resulting in shortages and rationing of diabetes medications (Alessi & Yankiv, 2022; Khan et al., 2019). Arguably, Liberia remains in a chronic crisis state due to a protracted civil war that severely weakened the health care system. Therefore, similar issues with access to life-saving diabetes medications were also prominent in our study.

The final theme of our study regarding the intersection of faith and diabetes is well-described in the literature, particularly how faith is commonly employed as a coping mechanism for dealing with the stresses of living with diabetes in resource-constrained settings (Abdoli et al., 2011; Ameyaw Korsah & Ameyaw Domfeh, 2020; Onyishi et al., 2022; Robbiati et al., 2022). A scoping review by Zimmermann et al. (2018) found that religious beliefs contributed to the treatment discourse of people living with diabetes in the sub-Saharan African context. The authors report that in situations of financial hardship, people living with diabetes commonly use prayer as a form of treatment. During our study, we often wondered if our participants’ reliance on their faith to cope with challenges of their illness was influenced by the neglect they experienced with diabetes services in Liberia. In essence, does a weak health care system breed a stronger reliance on religion for coping with the challenges of a chronic illness like diabetes?

The findings of our study support the need for several interventions within the Liberian health care system to improve outcomes for people living with diabetes. First, to address the challenges with food insecurity, we recommend the development of context-specific diabetes diet guidelines that focus on a variety of local foods that are healthy and cost-effective for people with diabetes. In addition, we recommend the development of food assistance programs for people with diabetes, as such a program would significantly ease the burden of food insecurity for people with diabetes in Liberia. In Maryland County, a sub-urban region in Liberia, a food assistance program has already been successfully rolled out for people with type 1 diabetes (Adler et al., 2021). This model could be adapted for Monrovia, an urban setting, to help address some of the challenges with access to food. Second, to address the issue of access to health services for people with diabetes, we recommend the development of diabetes clinics, integrated alongside secondary and tertiary levels of care to bridge the gap surrounding access to and continuity of care (Atun et al., 2017). Furthermore, local governments need to prioritize resources for people living with diabetes by providing consistent access to medications and diabetes supplies, as publicly funded hospitals are often a key point of access for people seeking services for diabetes management and care.

Beyond our research findings, we found the photovoice data collection method was a key strength of our study. This method allowed for meaningful engagement in the research project. Participants’ self-reflective inquiry into their situation enabled the creation of photographic evidence and symbolic representation of their unique experiences, helping others see their world through their point of view.

The main limitations to be noted for our study are related to the use of the ZoomTM videoconferencing platform for participant interviews. We recognize that using ZoomTM to collect our data limited our ability to respond to emotional cues and body language, which can be critically important in building rapport with participants during interviews. Establishing strong rapport with participants may provide better information due to the trust and understanding that can be built through this relationship.

5. Conclusion

This study fills an important gap in the existing literature on how contextual and structural factors influence the experience of living with diabetes in Liberia. We found that people living with diabetes encountered difficulties with access to food and health care services. To cope with the challenges of diabetes, people often relied on their faith for comfort. These findings demonstrate the need for additional research to explore what context-specific interventions are needed to address the barriers with access to food, medication, and health services for people living with diabetes. Our call to action is for local leaders and international partners to invest in sustainable programs and context-driven policies to help alleviate the burden of diabetes in Liberia.