1. Introduction - Housing as key to everyday life between privacy, privileges, and future potential

Providing sustainable housing solutions for all is also considered a key challenge of any sustainable local government policy worldwide (Smets & van Lindert, 2016, p. 5). In many Western countries, the doors to housing do not open in the same way for different target groups. Demand for housing is high, especially in metropolitan regions, resulting in a tight housing market where demand for housing exceeds supply. Rents and property prices are continuously rising. The housing supply is patchy and there is a mismatch between offers for affluent and less affluent citizens (Holm et al., 2021). The housing market is characterized by a variety of different groups, each with their own motivations and backgrounds. People are struggling with access to housing. Owners have different motives for (not) selling or renting vacant spaces. Stakeholders from business, politics, and society who influence housing policy and practice. The result is displacement processes (Mete, 2022), declining relocation mobility (Lebuhn et al., 2017), and housing vacancies (Beran & Nuissl, 2019, p. 18). Social inequality is omnipresent.

In Germany, it is commonplace to regulate unequal opportunities in the search for housing. The General Equal Treatment Act aims to prevent or end discrimination on the grounds of ethnic origin, gender, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual identity (Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency, 2019). The municipal level is responsible for providing numerous services of public interest, such as education, mobility and care infrastructures, as well as housing. However, municipal efforts to fulfill their missions encounter obstacles in the housing issue, as they cannot simply decide freely about the vacant properties. Moreover, they lack the funds for the construction of social housing. It becomes clear, that the concerns of owners, who want to participate in the housing market according to their own ideas, must be taken seriously.

In this scenario, the Dachau District (2023) in the wealthy commuter belt on the outskirts of Munich (Speckgürtel) has initiated the search for vacant housing in established housing structures in order to use existing (housing) capacities as rapidly as possible. The study entitled “Wohnungsleerstand wandeln! - Worthy places from un-used spaces!” (WohL) outlined here in this paper, looks behind the scenes with a multi-method research design. It uncovers motives, backgrounds and causes of housing vacancy. The study was funded by the Dachau District and the Bavarian State Ministry of Housing, Construction and Transport. One of the five research elements of the WohL Study is a Delphi Survey, whose outcome provided guidance on how to revitalize the stalled housing market. The quickest solution might be to make vacant housing available, but it must be kept in mind that housing is a matter of “like and like going together” (Fettke & Wacker, 2023). This requires designing and achieving a just transition (European Commission, 2019), so that the community wins in the process.

Participatory action research (von Unger, 2012; Zuber-Skerritt, 2015) is a proven method for identifying solutions to complex problems of local relevance by including people affected by the ongoing research (see section 2). Through the collaborative approach, interrelationships are to be recognized, and at the same time, processed in such a way that sustainable and just solutions can be found. In this research, social justice is approached by negotiation and deliberation as well as by applying jointly approved rules for democratic decision-making (Nugus et al., 2012). In terms of housing, participatory action research is a suitable approach based on the inclusion and interaction of multiple stakeholder groups.

In the WohL Study, factual and contextual knowledge about the local housing situation and related solutions was of pivotal interest. The Delphi method offers a discussion process in which complex issues, for which uncertainties and knowledge gaps exist, are clarified by experts in an iterative and structured process (Spranger et al., 2022, p. 2) aimed to find consensual solutions. At the same time, the method had to be capable of dealing with the diversity of perspectives inherent in housing as well as the principles of participatory action research.

In this regard, a qualitative approach was chosen as it is capable of taking individual experiences into account by striving for understanding and closeness to everyday practices as recommended by corresponding housing studies (Beran & Nuissl, 2019, p. 151). The state of research shows that there is no established literature about standards for qualitative Delphi Surveys, in particular. However, the current guidelines for reporting Delphi Surveys cover all methodological variants. Accordingly, information about justification, expert panel, questionnaire, survey design, process regulation, analyses, results, discussion as well as method reflection and ethics have to be included (Beiderbeck et al., 2021; Spranger et al., 2022).

Participatory action research, with its call for participant involvement in research, proximity to the field, and capacity building through mutual learning, is somewhat in tension with the more neutral information gathering of conventional Delphi Surveys. As the WohL Study seeks sustainable solutions to unequal housing conditions from different perspectives, a group discussion process, in which facts are listed by participants who remain anonymous without reflection on local social structures, may lead to conclusions about solutions that do not find acceptance. Therefore, this paper raises the question of how to design a Delphi Survey as a qualitative element of participatory action research.

To this end, the application of the WohL Delphi Survey is systematically reported and reflected upon. Moreover, the methodological findings obtained are reflected upon and trends in content are presented.

2. The WohL Study - Community-based Participatory Action Research for housing vacancy transformation

Involving diverse stakeholders in finding solutions requires openness, opportunity, and sensitivity to participation, for which qualitative research methods are developed. The search for solutions to identify ways of increasing diversity, equity (Gleichstellung), and inclusion (DEI) should involve stakeholders according to the equal opportunity approach (Ashley et al., 2022).

Participatory action research implies horizontal cooperation. In the WohL Study, the collaborative search by the municipalities of the district and the researchers follows the principle of Community-based Participatory Research (CbPR) (Duran & Wallerstein, 2003; Fine et al., 2021; Israel et al., 1998; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; von Unger, 2012; 2014; von Unger et al., 2007; Zuber-Skerritt, 2015). According to CbPR, horizontal cooperation starts with an agreement on a common research question. The cooperation is mutually beneficial because partners with common competencies and interests create the basis for a successful learning process. A joint undertaking isintended to create shared knowledge and insights, mutual trust, as well as social cohesion (Zuber-Skerritt, 2015) and constructive management of diverse interests and resources. With genuine participation, results will be sustainable as the people in the field have practical knowledge and interpretative authority (von Unger, 2012). However, the involvement of multiple stakeholders and the nature of participation are still seen as ‘tasks to be addressed’ (von Unger, 2012, p. 8).

The WohL Study is based on a common interest in developing measures to reduce housing vacancy. On the one hand, the communities know about the housing vacancy rates and the reasons for them, to some extent. On the other hand, researchers have access to scientific knowledge about housing vacancy and research methods. In a process of negotiation, research, and reflection among communities, stakeholders, and researchers vacant housing can be re-discovered for use through collaborative search processes with practice partners restructuring options for the future re-distribution of housing. The challenges of housing inequality (see section 2.1) and the applied multi-ethod design of CbPR are presented to illustrate the design of the WohL Study.

2.1 Pressure on the housing market, especially in metropolitan regions

There are numerous reasons for unequal housing opportunities, such as difficult access, high prices, and the spatial concentration of certain social groups in residential areas (Hinz & Auspurg, 2017, p. 401). Vulnerable to housing inequity are migrants, women, elderly and young people, tenants and households in urban areas, people with low incomes, precarious employment, low prestige, or educational disadvantage, single parents and large families (Atkinson, 2000, p. 158; Beran & Nuissl, 2019, p. 27; Dewilde, 2022, p. 374; FRA, 2007; Hinz & Auspurg, 2017; Ratcliffe, 2010).

In Germany, there is an ongoing change in housing demand as more and more people live alone during education, after a split or in old age, thus increasing the living space per capita housing and the number of single households (Statista, 2022). Against this background, the vacancy rate reduces the available housing space to the disadvantage of the above-mentioned groups.

Germany is known for a relatively high share of tenants who rely on landlords to provide housing.

The housing situation tends to be characterized by discrimination, particularly among the smaller housing providers (Beran & Nuissl, 2019). Owner behavior is seen as the cause of many vacancies in densely populated areas (Schmidt et al., 2017, p. 20), especially in tight housing markets. Hence, landlords have free choice and great options, thereby minimizing housing opportunities for certain groups of potential tenants.

To create sustainable housing, it is helpful to understand the underlying social mechanisms of unequal housing chances in more detail, as explained in the WohL Study conducted in the Dachau District. The district is geographically close to the City of Munich (Figure 1), one of the tightest housing markets in Germany (Voglmann et al., 2021, p. 406). The population density in the district is significant. This coincides with major differences in the economic, social and environmental situation in the communities. However, the ‘system-relevant’ professions, for example, health care staff and the police with low incomes, are nowadays struggling with housing problems everywhere.

As in other formerly rural regions, Dachau District is dominated by an infrastructure of single-family homes and large housing units (99 m² in 2019) (Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, 2019) and providers of small housing units. As a result, there are housing opportunities primarily for those who can afford a single-family home.

Currently, municipalities are hoping that they can solve many different challenges at once by addressing the issue of vacant housing because housing ‘system-relevant’ professions (such as health care staff members and police officers) are also considered to be their prime target groups. Moreover, they also need sustainable housing solutions to promote the heterogeneity of the population through participatory policies.

2.2 The Dachau District as pioneer and co-designer

In the WohL Study, CbPR builds capacity, for instance, by cooperating with local actors in committees that create the impetus and the structures for sustainable implementation of measures on the ground required for the desired pooling of competencies (Community-based Inclusion: CBI; e.g., in health care; Nguyen et al., 2021). Accompanying structures exist, such as a Council of Municipalities, in which mayors are active.

In Germany, mayors are at the helm of local government. As elected political representatives of the municipalities, they have a comprehensive overview of local people's perspectives on vacant housing as well as on access to the housing market.

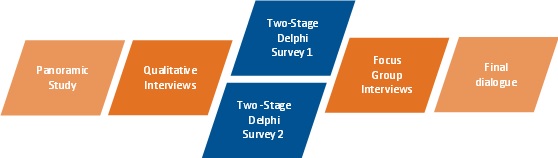

In addition, the research team of the WohL Study is advised twice a year by a Steering Committee of local civil society, political, and administrative representatives. As there are many meetings, the documentation of the exchanged thoughts and results through minutes is a central element, supplemented by regular newsletters on proceedings. The five study components (Figure 2) are designed to collect data about different demands and perspectives on housing.

An initial overview of the field combining different perspectives was gained by conducting a Panoramic Study with desktop research on the Dachau District and its municipalities, and furthermore, included field excursions by the researchers (Grube & Thiele, 2020). The next intermediate step, the qualitative Delphi Survey on the situation in the housing market, on possibilities for the (re)use of vacant housing, including possible responses of the municipalities, involved local experts. Currently (February 2023), qualitative interviews (Witzel & Reiter, 2012) with owners of vacant housing are taking place to elicit the individual motivations and backgrounds of people who do not rent out their spaces. This will be followed by focus group interviews (Schulz et al., 2012) in which owner types will explore attractive options for repurposing their vacant housing. Finally, the results are discussed in a dialogue with the public.

In summary, the WohL Study relies on the participation of local people. Particular attention is paid to a holistic view that leads to a sustainable, multi-stakeholder solution taking into account local needs, diversity, and existing structures.

3. Delphi Survey as a discovery tool

The Delphi process is divided into three interrelated components: preparation, implementation, and analysis (Beiderbeck et al., 2021). The participants contribute knowledge and experience on a specific topic area (Nasa et al. 2021, p. 119) by answering a series of questions analyzed by researchers in an anonymous format. The experts are then informed of the results obtained and allowed to reconsider or revise their assessments. The intention is to explore different possible options for action by creating opportunities for reflection and consensus-building. While the conventional Delphi Survey is usually based on a standardized questionnaire and statistical analysis with typically two rounds of data collection, there are several alternatives to the Delphi Survey applied in different ways (Spranger et al., 2022).

A qualitative approach is characterized by openness, flexibility, and sensitivity to the diversity of perspectives (Sekayi & Kennedy, 2017) and recurrent interpretations (Guyz et al., 2015). As a qualitative element of CbPR, the Delphi Survey must be designed to be sensitive to inequalities and social diversity, to build capacity through mutual learning and to direct involvement of the communities in design decisions as well as, in the case of the WohL Study, to promote awareness of existing inequalities in housing. The exploration and assessment of the local housing situation and solutions, supported by multiple professional perspectives with local relevance, make the Delphi Survey a platform for shared learning and change (Zuber-Skerritt, 2015).

The following section explains the basic design decisions of the WohL Delphi Survey by presenting the expert panel, questionnaire, survey design, process control, and analysis.

3.1 Basic characteristics of the Delphi Survey

Basic decisions about the Delphi Survey, as described, include the stages of the group process, selection of participants, as well as procedures for data collection, analysis and feedback. Considerations of consensus and anonymity had to be balanced with concerns for the sustainability of solutions and the diversity of perspectives.

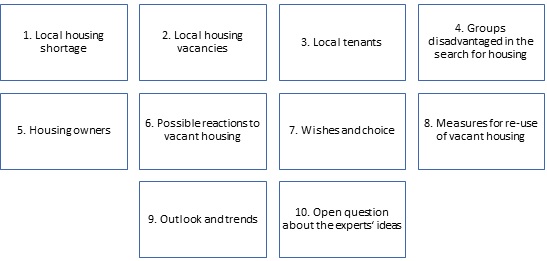

The Delphi Survey was designed as a two-stage process. Experts were selected based on perceptions of their knowledge and experiences (Guyz et al., 2015) regarding housing in the Dachau District. Fifteen mixed female and male representatives from the fields of civil society, social affairs, politics, administration, law and business were selected on the assumption that the housing market includes cultural, economic, political, social and technical dimensions. Thus, there was a representative of tenants, of property owners, a lawyer specializing in inheritance law, and persons representing vulnerable groups in the housing market (Figure 3). The recruiting was carried out by the municipalities themselves.

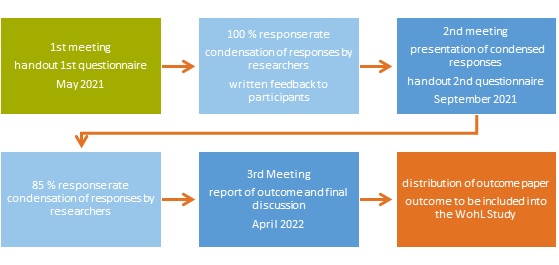

Data collection in the Delphi Survey had a specific sequence. A meeting to introduce the topic, the WohL Study and the Delphi Survey schedule as well as the research team was followed by submitting a completed questionnaire via e-mail. In the two-stage Delphi Survey, data were collected via minutes and questionnaires. The minutes were sent to the participants after each session with a request for additions or revisions (Figure 4). The first meeting was held via Zoom, due to the Corona pandemic and restrictions on face-to-face meetings. There, it was soon apparent that most of the experts knew each other anyway, which is no surprise in this particular setting.

The questionnaires contained blocks of open-questions and open response boxes. The anonymity of the written answers was guaranteed. According to ethical principles (Keeney et al., 2001, p. 199), the answers were also processed in anonymous form in the WohL Study’s so-called ‘inner circle’. The experts answered the questions at home and individually. The researchers recorded the responses and produced a condensed text. The goal was to cover the full range of responses. A consensus on the balance of housing vacancy and its impact by experts from different fields and with different personal backgrounds was not very likely. The results were reflected in the subsequent meeting of experts during a group discussion.

For the first stage, questions were created based on the description of the local situation and on common approaches to solutions according to the state of knowledge in the scientific literature and the Panoramic Study, the latter informing about the perspectives of the practice. 51 items concerned the situation in the local housing market, the circumstances of housing supply and possible responses to vacant housing (Figure 5). In the second stage, there was a discussion of mirrored responses and additional questions from the literature (Bourgeois et al., 2006) in order to assess the level of agreement and support for the shared perspectives that the researchers had identified from the draft text.

Using qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2000), the researchers abridged the list of responses from stage one (90 pages) to 20 pages (step 2), and finally, to 10 pages for an outcome paper summarizing the findings.

To do this, the researchers first read the feedback for each question independently, and then, the entire texts of the respective experts. This allows the categories to be determined and the range of responses for each question to be identified. As in Mayring’s (2000) cross-sectional analysis, experts’ responses were used to identify statements and context. Individual themes and areas of agreement and disagreement were summarized to present the outcomes. The response rates were 100 percent for the first stage, 85 percent for the second stage, and 90 percent for the closing meeting. Those who did not return the second questionnaire were not identical with those who could not attend the closing meeting, confirming that the experts consulted were successfully included in the Delphi Survey. In this respect, it was possible to obtain a comprehensive picture of opinions without any dropouts of specific expertise.

The Delphi outcome paper was given to the experts and sent to the municipalities and the Bavarian State Ministry. The Delphi Survey thus captured the experts' assessments of the housing situation in the Dachau District and of sustainable solutions across the entire spectrum of action, while at the same time, allowing the experts to learn from one another.

3.2 Findings of the Delphi Survey

In terms of outcome, there was agreement on the basic thesis that there is less social diversity in the Dachau District, which is due to housing. Proximity to Munich is seen as a cause for the exceptionally high demand for housing. For the experts, the local housing shortage is a central component of the municipal setting of tasks. At the same time, many owners feel neither economic pressure nor a socially motivated inclination to re-rent. When property owners rent out, they prefer people who seem familiar - and because people in the district are quite affluent, better-off households have an advantage. Social similarity (Robbins & Judge, 2015 regarding origin, language, cultural habits, physical appearance) or a recognized high social status (a prestigious position or a secure financial situation) is preferred.

Those who are vulnerable due to their socioeconomic status and other social desirability criteria are disadvantaged in the local housing market as well as system-relevant low-income professionals. Compared to the findings of housing literature, there are other particularly vulnerable social groups in the Dachau District including people considered by property owners to be socially unequal, namely, deviating from expected normalcy, like people with large pets, and people who have little financial cushion to absorb increases in rent and utility costs.

For the Delphi experts, the current trends are gradually homogenizing the communities. Since many areas of community life depend on social diversity in the long run, residents undermine their chances for a high quality of life. The fact that some professional groups can no longer find housing and migrate to neighboring districts illustrates that there are corresponding consequences for the potential quality of life for all.

Overall, the WohL Delphi Survey was adapted to accommodate the research design as an element of CbPR, thereby facilitating a group process sensitive to inequalities and social diversity, and encouraging mutual learning.

4. Housing in change - a test run challenge with CbPR entanglement

Justifications and results of the WohL Delphi Survey as a qualitative element of CbPR are discussed in order to recommend the applied method for detecting sustainable solutions in a community-based way. The basic decisions are included.

According to scientific literature, the study of housing inequality demands openness and sensitivity to participation. The Delphi Survey considered demands and diversity, even if it builds on existing structures, as is typical for CbPR. The decision to use a qualitative element included considerations of the project partners’ demands for sustainable solutions. The corresponding principles of CbPR and the conventional Delphi Survey recommend the qualitative approach as well, especially for the heterogeneity of perspectives necessary for reflection on housing structures and practices, for their respective organization in the field, and for the development of approaches to solutions. The experts’ high participation and perseverance loyalty during the Delphi Survey confirm the choice of method.

The choice is also supported by the outcome. In line with CbPR principles, the experts’ statements provide a solid basis for identifying necessary interventions and planning for future actions, taking into account local conditions, which means that discrimination concerning social groups is more strongly mapped.

The two-stage design proved successful. Reminders were necessary but can be attributed to the time dedicated to answering the questionnaires. The high response rate proves a strong commitment to the topic, as does the fact that those who dropped out in stage two were not identical with those who attended the closing meeting with the outcome presentation. Therefore, this suggests the appropriateness of the methodological tool.

As the WohL Study seeks acceptable solutions to housing vacancy, locally based perspectives that have been stimulated to reflect are a fruitful approach for sustainability and acceptance. Vulnerable groups were included through selected representatives to ensure proximity to everyday life. However, from a critical perspective (Fine et al., 2021), the inclusion of marginalized perspectives through representation goes against CbPR principles. However, since representatives draw on cross-case knowledge, and there is an ethical dimension to discussing housing solutions without accommodation with people in need of housing, inclusion through representation is a reasonable choice.

The method of analysis was selected by taking into consideration data collection, process integration, and researcher resources. From the CbPR perspective, the design of the Delphi Survey requires cooperation, accounting for resources and technical aspects. As a part of the Delphi Survey, researchers developed questionnaires and conducted a qualitative content analysis. The research partners agreed to the tools and provided explanations if certain statements remained unclear to the researchers. The collection of written responses and the need for condensation into an abbreviated and polished text argued for cross-sectional content analysis. Methods more sensitive to the context of data collection, such as the Grounded Theory, are not designed to abridge texts and are thus appropriate for narrative settings. Nevertheless, including responses and collective discussions allow for context-sensitive results and prepare for consensus building. In terms of methods, it can be concluded that the form of participation must be tailored to the topic of study and the participants involved.

Furthermore, as an element of CbPR, the Delphi Survey was designed for consensus building in a field with divergent perspectives. The outcome mirrors the jointly adopted situation description and recommendations reflecting on different perspectives. In general, the conventional Delphi Survey is quite often criticized for forcing consensus and for not allowing for discussion and elaboration of perspectives by participants (Keeney et al., 2001, p. 198). Nevertheless, the face-to-face discussions in the WohL Delphi Survey offer both confidentiality and proximity to the settings. After the Delphi Survey, solutions have to prove themselves in the real life of communities, hence, in an environment where there is no anonymity anyway.

For future research, quantitative studies are helpful to gain a comprehensive picture of the housing situation. This paper documents that qualitative methods contribute to identifying individual experiences, understanding, and proximity to everyday practice. It is difficult to determine qualitative criteria of rigor because there is the need for adaption to the context, in turn, allowing for unique insights into solutions for multidimensional issues. Nevertheless, some characteristics are unique to qualitative Delphi Surveys, such as the type of questionnaire, evaluation and consensus, and the number of stages that can be conducted.

5. Does the housing vacancy stimulate the sustainable development of the housing demand?

The Dachau District is undoubtedly a region in transition when it comes to housing. A simple "business as usual" approach cannot lead to the impact desired. Evidence of social selectivity shows that the (re)use of vacant housing alone does not solve the housing puzzle. Instead, the (re)use of vacant housing should also be an incentive to discuss common selection criteria of housing decisions by property owners.

It is only when it concerns the social component that economic and environmental sustainability in housing, for instance, reduced resource consumption and cost savings can come into play. Thus, it is important to look for efficient and effective support measures during the transition period. For this purpose, the outcome of the Delphi Survey can be used directly for the framing of possible measures.

Housing opportunities in this sense of community would represent great strides, but the potential groups of people involved have yet to recognize and take on their roles in community development. The ongoing alignment of good lessons learned in transformation needs to be incorporated into daily life as well.

If the appropriate infrastructure can be created, the Dachau District could develop into a future ‘laboratory’ for housing through municipal activities, with many followers. The first step would be to encourage and activate the community to participate in the processes of transformation, the direction of which has been outlined in this paper in an evidence-based manner.

The use of CbPR methods has the potential to initiate a transformation. In the case of the pressing need for housing through access to existing housing resources, it proves to be an appropriate tool, because to move forward, it is important to access the existent housing supply as well. It is in line with the concept of just change, which embedded in the distribution of tasks in a social market economy with federal substructures is purposeful and helpful. CbPR allows for an orientation for action addressing the ecological, economic, political, and social dimensions of structural disadvantages evident in living conditions. The mechanisms of the housing market often reinforce the inequalities as intersections are reproduced. The inequalities have to be reflected in their intersectionality, in favor of an orientation for action that is aware of the existing infrastructures and contexts that hinder or promote them. In this way, the supportive infrastructure of the future can be developed without disregarding individual viewpoints. However, such processes also require designs that incorporate the impacts focus, and this is where methodological choices and research come into play. As with mining, it is not surprising that the effort is not entirely free, but existing treasures may come to light or clues to upcoming values may be discovered. The effort is worthwhile for the transformation of vacant housing.

This project was supported by the Dachau District and the Bavarian State Ministry for Housing, Construction and Transport. We would like to thank our local partners, especially the municipal administrations and the mayors. The authors would also like to sincerely thank Elizabeth Hamzi-Schmidt for her final language polish.